9,60 €

Mehr erfahren.

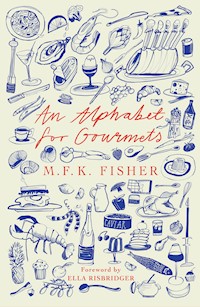

- Herausgeber: Daunt Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

From A for (dining) Alone to Z for Zakuski, (a Russian hors d'oeuvre), An Alphabet for Gourmets is an anthology of food essays by the incomparable M. F. K. Fisher, alighting on long-time obsessions and idiosyncratic digressions to wholly charming effect.Admired by W. H. Auden as one of the greatest American writers, M. F. K Fisher never focuses on just the food set before her. Instead, with unfailingly elegant prose, an eye for evocative detail and a knack for sharp-edged wit, she draws us in to the whole experience: from the company to the setting, from the preparation to the scraped-clean plate. She liberates her readers from caution, sweeps away adherence to culinary tradition, and celebrates cooking, eating and dining in all its guises.Evocative, thoughtful, with a light touch and a wry humour, these essays illustrate with captivating ease why M. F. K. Fisher has become one of the most beloved and admired food writers of the twentieth century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

‘She is not just a great food writer. She is a great writer, full stop.’ Rachel Cooke, Observer

‘Poet of the appetites.’ John Updike

‘Fisher’s decadent, sensuous food writing remains pure self-care.’ Independent

Also by M.F.K. Fisher

Serve it Forth

Consider the Oyster

How to Cook a Wolf

The Gastronomical Me

Here Let us Feast: A Book of Banquets

Not Now But Now

The Physiology of Taste (as translator)

A Cordial Water

Map of Another Town

With Bold Knife and Fork

Among Friends

A Considerable Town

As They Were

Sister Age

Long Ago in France

Measure of Her Powers: An M. F. K. Fisher Reader

The Theoretical Foot

For Hal Bieler; Who taught me more than he meant to about the pleasures of the table

Contents

Introduction

I met Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher when I was twenty-three. She was twenty-three years dead by then, but it didn’t matter: we had a lot to say to each other.

We met in the footnotes of an eighteenth-century Meditation on Transcendental Gastronomy. The book was by someone with the stupendous name of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin but translated by a person with the unpromisingly dry name of M.F.K. Fisher. I was in it for the Brillat-Savarin, and to look clever, but it was much funnier – much sharper and smarter – than any translation of eighteenth-century philosophy I had ever read. This, I came quickly to see, was because Mary Frances had done the translation.

I had bought the book in a bookshop in Rome on a whim. I was in Rome trying to be a person who ate alone, and I was happy and lonely; and there was Mary Frances, annotating the text with lavish disregard for convention and a recipe for syllabub.

‘Last night in Hollywood I was served something very far removed from butter,’ she remarked, archly, across the table. She was speaking 150 years into her past; and seventy years into her future. Brillat-Savarin and I were both listening. There is something about Mary Frances that makes a person listen when she speaks, even in footnotes, even in translator’s glosses.

I turned the page and reached for the platter of fried courgette flowers.

‘Every city with any claim to vitality,’ said Mary Frances, her gaze on the glossy, plump, pollen-spattered fiori di zucca, ‘capitalises on the obvious connection of the pleasures of the couch and the pleasures of the table.’ I read it again; did a small, dignified double-take at the outrageous sexiness of this academic footnote. I checked the dates of the book: 1755 for Brillat-Savarin and 1949 for M.F.K. Fisher. Did Mary Frances really mean that? She did, and I loved her for it. I loved her, to be frank, on sight.

She was a food writer, and so was I; and we both loved oysters, and the mountains around Lake Geneva, and men who were dying. We were both people who wrote about dying men; and who had loved women; and who felt things, I thought, with a sort of bone-deep and earth-shaking sort of feeling. We both liked things the way we liked them; and we were both trying to understand how to go on living when the person we loved more than life was going, and then— had gone.

As with any astoundingly famous friend, it is a little hard for me to comprehend the scale of her success; as with any beloved author, I am privately disbelieving that anyone else has ever read her at all. Her books, I think, are letters to me: she left them for me, so that I wouldn’t be alone.

No matter that M.F.K. Fisher and I never existed in the world at the same moment; no matter that W. H. Auden spoke of her as the greatest American prose stylist; no matter that she wrote fifteen books and won the James Beard Lifetime Achievement Award. She is my private friend, my private consolation. How can she belong to everybody?

But then, food writing always walks a fine line between the public and the private.

There is no way to write about food that does not reveal the inside of your mouth, or the inside of your mind: no way to tell what you think is good to eat without someone else knowing what you think is good to eat. It is always an exposure of habit and culture and – most overwhelmingly – delight. Even in the most strictly anodyne of cookbooks, the taste of the writer prevails. This is what I cook; this is what I think you should cook, and how you should cook it; how salty, how bitter, how sweet. This is what is good to me; I believe it will be good for you, too. Make this the way I make it. Taste what I taste.

It’s the thing that crosses the boundary between writer and reader; the careful delineation of how your hands might mimic mine might mimic Fisher’s, and how we might therefore experience the same thing. It is intimate in a way we never think about: Fisher’s fingers on my lips, and mine on yours.

And yet Fisher must have thought of it. She knew, right from the start, that to write about food is to write about intimacies: both the expected intimacies, of lovers and mothers and daughters, but also of the unexpected and the erotic and the strange and the queer. ‘I was in love with all these people,’ she writes. ‘And I was richly rewarded for doing so.’

Her books are frank about sex, and desire, and love: about a first oyster in the arms of an older-girl first crush; about eating grapes from a stranger’s navel as a young bride; about bearing witness to the love of a Mexican trans musician for her younger brother. All this she embraces; all this she writes about when she is writing about food.

‘Why do you write about food and eating and drinking?’ she once imagined herself being asked. ‘Why don’t you write about the struggle for power and security, and about love, the way others do?’ For Fisher – and to her readers – the answer is obvious: everything is sex, except sex, which is power: a possible paraphrase of Oscar Wilde, but which came to me through the great queer icon Janelle Monáe and which seems, in a strange and necessary way, to be the same force that drives M.F.K. Fisher’s food writing. And there is a force behind it.

Fisher is so direct, so clear, in her opinions that one cannot help but be swept away by them – even when they don’t accord with one’s own. There is no arguing with Fisher; on any subject she is the cleanest and coolest of commentators. ‘It is rare to be happy in a group,’ she says, with authority; a little later that scrambled eggs ‘would be much more … edible without … salt’. It does not occur to her to brook any disagreement with her thoughts: she is, here, the last word.

You sort of expect this from a recipe writer – or you hope for it – but it’s unusual to come across such firm clarity in a book of essays. At least, it is now: the most dated thing about Fisher’s work is that she apologises for nothing and asks for apology from nobody. There is no fluffiness to Fisher: no excuses, no softening, even for herself. She examines her own behaviour with the same detached, almost architectural eye with which she considers the places she finds herself. She is not afraid of her own life, or her own work; she is not afraid to say exactly what she intends to say. She speaks plainly and in absolute terms. She does not dither. She does not fuss, and there is something profoundly soothing about her brisk and beautiful speech.

I think a lot of good food writing has this kind of authority to it, not just in the instructions themselves but in the tone of it: and maybe it’s the same with good food itself. There is a simplicity and clarity to the kind of cooking Fisher most admires, and – perhaps because I have just finished reading An Alphabet for Gourmets – the kind of cooking I admire, too. My own tastes – messy, and less civilised than Fisher’s, and even leaning occasionally to instant noodles and things from tins – seem very distant. I would like to eat some steamed green vegetables, the way Fisher cooks them for her little daughters ‘in the four-quart Presto’; I would like a saucepan of freshly picked peas and some little dark brown roasted chickens, left to cool in their own juices; I would like, possibly, some plain salted potato chips. I long to be taken to a restaurant where somebody sensible has already ordered for me (!), the way Fisher does with her rich friend (‘I hate menus’), and already arranged for the bill to be sent, later, to her house.

The thing about Fisher’s writing is that she is an artist – and a student – of the appetite. It makes you hungry to read her work. This is not, really, because of the recipes: ‘Hindu eggs’, ‘milk toast’ and ‘kidneys Ali-Bab-ish’ may jar in more ways than one, but they are basically beside the point. The point is not the food itself, but the hunger for it: the desire, and the satisfaction of the desire.

You can feel it when you read: that old tension between the public and the private, held between the dry pages of her book, and her living throat and tongue and hands.

She is that rare narrator who exists both within the story, and outside it. There is a detached quality to her – a foreigner simultaneously in America, in Europe, in her family, in her marriages – and yet she is deeply, overwhelmingly sensual and sexual and unabashed and unashamed. Her prose is both unnervingly intimate and tautly distant.

She wants us to stay away, but come close, or, perhaps – she wants someone else to come close and we will do as substitute. We will do, while she waits.

An Alphabet for Gourmets, published the year her third marriage broke down, and eight years after her second husband Chexbres killed himself, is written with the bracing aloofness of a person who has lost a great deal.

Her second husband, an artist, had died by suicide in 1941 after a long degenerative illness; after his death she is, she says, a ‘ghost’ forever.

So the love of her life is gone; and the war has taken their beloved Switzerland from her; she has lost her French friends, some dead, and some disappeared. She has lost her brother, also dead by suicide, and her mother. She is caring for her unwell elderly father; and her current husband – ‘married by accident’ – has led them deeply into debt, been hospitalised for a psychosomatic stomach disorder, and is about to leave her. She has one daughter, aged about six, and another, aged about three. The war has changed everything. Everything is gone, and going, in 1949.

A ghost, maybe, but a hungry ghost: a ghost who has no choice but to write, not just for art’s sake, but to survive.

Mary Frances has lost what mattered to her and now she will tell you the truth because she has nothing else to lose, and nothing else to say.

And then what should she write? How should she write? Everything is gone, yet she is still alive. What is a person supposed to do with that? How should a person be at the end of the world? These are not supposed to be the questions of food writers, I think. They weren’t then, and I don’t think they are now: they are not comfortable to think about when planning a menu.

Fisher writes about her present – about the America of the forties, about feeding her children – and about her childhood, but the moments of radiant happiness in this book (and all her books) come from the life she shared with Chexbres, in Switzerland.

Her parents come; they pick peas together, the four of them, with their friends.

‘God, but I feel good!’ her father calls, as he picks the peas, joyous and strong, and she finds herself inexplicably near tears. I am almost in tears just writing about it; and writing about her writing about it, a decade later, her father infirm, and her mother dead, and Chexbres dead too, and recalling this moment of perfect happiness: recalling it with such clarity that I remember it, too.

There is an essay in this book – of course one about Switzerland, and Chexbres – where they drive up the mountain, and drink extraordinary champagne together. The champagne, because of the atmospheric pressure, exists only at altitude. When they take it down the mountain it becomes merely a ‘pretty pink drink’. Like happiness, it can’t be tamed: it lights where it lights. The fizz exists only in that time and place.

Nobody even seems sure if their house in Switzerland exists anymore, and everyone who lived there is dead.

Mary Frances, my friend, is dead; and so is Brillat-Savarin. So is the person I loved when I first met them both. The world has changed and it keeps on changing. And I am still here; and so are you. And so, because of us both – the way we read, the book we both hold in our hands – is Mary Frances. In her writing she makes Chexbres alive again; and in our reading we make them both so; and in reissuing this book that is out of print the champagne is – voila! – champagne again, and everyone is alive, and eating peas.

Foreword

It is apparently impossible for me to say anything about gastronomy, the art and science of satisfying one of our three basic human needs, without involving myself in what might be called side issues – might be, that is, by anyone who does not believe, as I do, that it is futile to consider hunger as a thing separate from people who are hungry.

That is why, when I set myself to follow anything as seemingly arbitrary as an alphabet, with its honoured and unchanging sequence and its firm count of twenty-six letters, I must keep myself well in hand lest I find A Is for Apple, B Is for Borscht, and C Is for Codfish Cakes turning into one novel, one political diatribe, and one nonfiction book on the strange love-makings of sea monsters, each written largely in terms of eating, drinking, digesting, and each written by me, shaped, moulded, and, to some minds, distorted by my own vision, which depends in turn on my state of health, passion, finances, and my general glandular balance.

If a woman can be made more peaceful, a man fuller and richer, children happier, by a changed approach to the basically brutish satisfaction of hunger, why should not I, the person who brought about that change, feel a definite and rewarding urge to proselytise? If a young man can learn to woo with cup and spoon as well as his inborn virility, why should not I who showed him how feel myself among Gasterea’s anointed? The possibilities for bettering the somewhat dingy patterns of life on earth by a new interest in how best to stay our human hunger are so infinite that, to my mind at least, some such tyrannical limitations as an ABC will impose are almost requisite.

The alphabet is also controversial, which in itself is good. Why, someone may ask, did I scamp such lush fields as L Is for Lucullus, G Is for Gourmet? Why did I end the alphabet with a discussion of the hors d’oeuvres called zakuski, surely more appropriate at the beginning of any feast, literary or otherwise, and ignore the fine fancies to be evoked by the word zabaglione, with all its connotations of sweet satisfaction and high flavour?

I do not really know, but most probably because I am myself. This ABC is the way I wrote it. There is room between its lines, and even its words, for each man to write his own gastronomical beliefs, call forth his own remembered feastings, and taste once more upon his mind’s tongue the wine and the clear rock-water of cups uncountable.

A is for dining Alone

… and so am I, if a choice must be made between most people I know and myself. This misanthropic attitude is one I am not proud of, but it is firmly there, based on my increasing conviction that sharing food with another human being is an intimate act that should not be indulged in lightly.

There are few people alive with whom I care to pray, sleep, dance, sing or share my bread and wine. Of course there are times when this latter cannot be avoided if we are to exist socially, but it is endurable only because it need not be the only fashion of self-nourishment.

There is always the cheering prospect of a quiet or giddy or warmly sombre or lightly notable meal with ‘One’, as Elizabeth Robins Pennell refers to him or her in The Feasts of Autolycus. ‘One sits at your side feasting in silent sympathy,’ this lady wrote at the end of the last century in her mannered and delightful book. She was, at this point, thinking of eating an orange1 in southern Europe, but any kind of food will do, in any clime, so long as One is there.

I myself have been blessed among women in this respect – which is of course the main reason that, if One is not there, dining alone is generally preferable to any other way for me.

Naturally there have been times when my self-made solitude has irked me. I have often eaten an egg and drunk a glass of jug-wine, surrounded deliberately with the trappings of busyness, in a hollow Hollywood flat near the studio where I was called a writer, and not been able to stifle my longing to be anywhere but there, in the company of any of a dozen predatory or ambitious or even kind people who had not invited me.

That was the trouble: nobody did.

I cannot pretend, even on an invisible black couch of daydreams, that I have ever been hounded by Sunset Boulevardiers who wanted to woo me with caviar and win me with Pol Roger; but in my few desolate periods of being without One I have known two or three avuncular gentlemen with a latent gleam in their eyes who understood how to order a good mixed grill with watercress. But, for the most part, to the lasting shame of my female vanity, they have shied away from any suggestion that we might dally, gastronomically speaking. ‘Wouldn’t dare ask you,’ they have murmured, shifting their gaze with no apparent difficulty or regret to some much younger and prettier woman who had never read a recipe in her life, much less written one, and who was for that very reason far better fed than I.

It has for too long been the same with the ambitious eaters, the amateur chefs and the self-styled gourmets, the leading lights of food-and-wine societies. When we meet, in other people’s houses or in restaurants, they tell me a few sacrosanct and impressive details of how they baste grouse with truffle juice, then murmur, ‘Wouldn’t dare serve it to you, of course,’ and forthwith invite some visiting potentate from Nebraska, who never saw a truffle in his life, to register the proper awe in return for a Lucullan and perhaps delicious meal.2

And the kind people – they are the ones who have made me feel the loneliest. Wherever I have lived, they have indeed been kind – up to a certain point. They have poured cocktails for me, and praised me generously for things I have written to their liking, and showed me their children. And I have seen the discreetly drawn curtains to their family dining-rooms, so different from the uncluttered, spinsterish emptiness of my own one room. Behind the far door to the kitchen I have sensed, with the mystic materialism of a hungry woman, the presence of honest-to-God fried chops, peas and carrots, a jello salad,3 and lemon meringue pie – none of which I like and all of which I admire in theory and would give my eyeteeth to be offered. But the kind people always murmur, ‘We’d love to have you stay to supper sometime. We wouldn’t dare, of course, the simple way we eat and all.’

As I leave, by myself, two nice plump kind neighbours come in. They say howdo, and then goodbye with obvious relief, after a polite, respectful mention of culinary literature as represented, no matter how doubtfully, by me. They sniff the fine creeping straightforward smells in the hall and living-room, with silent thanks that they are not condemned to my daily fare of quails financière, pâté de Strasbourg truffé en brioche, sole Marguéry, bombe vanille au Cointreau. They close the door on me.

I drive home by way of the corner Thriftimart to pick up another box of Ry Krisp, which with a can of tomato soup and a glass of California sherry will make a good nourishing meal for me as I sit on my tuffet in a circle of proofs and pocket detective stories.

It took me several years of such periods of being alone to learn how to care for myself, at least at table. I came to believe that since nobody else dared feed me as I wished to be fed, I must do it myself, and with as much aplomb as I could muster. Enough of hit-or-miss suppers of tinned soup and boxed biscuits and an occasional egg just because I had failed once more to rate an invitation!

I resolved to establish myself as a well-behaved female at one or two good restaurants, where I could dine alone at a pleasant table with adequate attentions rather than be pushed into a corner and given a raw or overweary waiter. To my credit, I managed to carry out this resolution, at least to the point where two headwaiters accepted me: they knew I tipped well, they knew I wanted simple but excellent menus, and, above all, they knew that I could order and drink, all by myself, an apéritif and a small bottle of wine or a mug of ale, without turning into a maudlin, potential pick-up for the Gentlemen at the Bar.

Once or twice a week I would go to one of these restaurants and with carefully disguised self-consciousness would order my meal, taking heed to have things that would nourish me thoroughly as well as agreeably, to make up for the nights ahead when soup and crackers would be my fare. I met some interesting waiters: I continue to agree with a modern Mrs Malaprop who said, ‘They are so much nicer than people!’

My expensive little dinners, however, became, in spite of my good intentions, no more than a routine prescription for existence. I had long believed that, once having bowed to the inevitability of the dictum that we must eat to live, we should ignore it and live to eat, in proportion of course. And there I was, spending more money than I should, on a grim plan which became increasingly complicated. In spite of the loyalty of my waiter-friends, wolves in a dozen different kinds of sheep’s clothing – from the normally lecherous to the Lesbian – sniffed at the high wall of my isolation. I changed seats, then tables. I read – I read everything from Tropic of Cancer to Riders of the Purple Sage. Finally I began to look around the room and hum.

That was when I decided that my own walk-up flat, my own script-cluttered room with the let-down bed, was the place for me. ‘Never be daunted in public’ was an early Hemingway phrase that had more than once bolstered me in my timid twenties. I changed it resolutely to ‘Never be daunted in private’.

I rearranged my schedule, so that I could market on my way to the studio each morning. The more perishable titbits I hid in the water-cooler just outside my office, instead of dashing to an all-night grocery for tins of this and that at the end of a long day. I bought things that would adapt themselves artfully to an electric chafing dish: cans of shad roe (a good solitary dish, since I always feel that nobody really likes it but me), consommé double, and such. I grew deliberately fastidious about eggs and butter; the biggest, brownest eggs were none too good, nor could any butter be too clover-fresh and sweet. I laid in a case or two of ‘unpretentious but delightful little wines’. I was determined about the whole thing, which in itself is a great drawback emotionally. But I knew no alternative.

I ate very well indeed. I liked it too – at least more than I had liked my former can-openings or my elaborate preparations for dining out. I treated myself fairly dispassionately as a marketable thing, at least from ten to six daily, in a Hollywood studio story department, and I fed myself to maintain top efficiency. I recognised the dull facts that certain foods affected me this way, others that way. I tried to apply what I knew of proteins and so forth to my own chemical pattern, and I deliberately scrambled two eggs in a little sweet butter when quite often I would have liked a glass of sherry and a hot bath and to hell with food.

I almost never ate meat, mainly because I did not miss it and secondarily because it was inconvenient to cook on a little grill and to cut upon a plate balanced on my knee. Also, it made the one-room apartment smell. I invented a great many different salads, of fresh lettuces and herbs and vegetables, of marinated tinned vegetables, now and then of crabmeat and the like. I learned a few tricks to play on canned soups, and Escoffier as well as the Chinese would be astonished at what I did with beef bouillon and a handful of watercress or a teaspoonful of soy.

I always ate slowly, from a big tray set with a mixture of Woolworth and Spode; and I soothed my spirits beforehand with a glass of sherry or vermouth, subscribing to the ancient truth that only a relaxed throat can make a swallow. More often than not I drank a glass or two of light wine with the hot food: a big bowl of soup, with a fine pear and some Teleme Jack cheese; or two very round eggs, from a misnamed ‘poacher’, on sourdough toast with browned butter poured over and a celery heart alongside for something crisp; or a can of bean sprouts, tossed with sweet butter and some soy and lemon juice, and a big glass of milk.

Things tasted good, and it was a relief to be away from my job and from the curious disbelieving impertinence of the people in restaurants. I still wished, in what was almost a theoretical way, that I was not cut off from the world’s trenchermen by what I had written for and about them. But, and there was no cavil here, I felt firmly then, as I do this very minute, that snug misanthropic solitude is better than hit-or-miss congeniality. If One could not be with me, ‘feasting in silent sympathy’, then I was my best companion.

1

Probably the best way to eat an orange is to pick it dead-ripe from the tree, bite into it once to start the peeling, and after peeling eat a section at a time.

Some children like to stick a hollow pencil of sugar-candy through a little hole into the heart of an orange and suck at it. I never did.

Under the high-glassed Galeria Vittorio Emanuele in Milan before the bombs fell, the headwaiters of the two fine restaurants would peel an orange at your table with breathtaking skill and speed, slice it thin enough to see through, and serve it to you doused to your own taste with powdered sugar and any of a hundred liquors.

In this country Ambrosia is a dessert as traditionally and irrefutably Southern as pecan pie. My mother used to tell me how fresh and good it tasted, and how pretty it was, when she went to school in Virginia, a refugee from Iowa’s dearth of proper fin de siècle finishing schools. I always thought of it as old-fashioned, as something probably unheard of by today’s bourbons. I discovered only lately that an easy way to raise an unladylike babble of protest is to say as much in a group of Confederate Daughters – and here is the proof, straight from one of their mouths, that their local gods still sup on

Ambrosia

6 fine oranges

1½ cups grated coconut, preferably fresh

1½ cups sugar

good sherry

Divide peeled oranges carefully into sections, or slice thin, and arrange in layers in a glass bowl, sprinkling each layer generously with sugar and coconut. When the bowl is full, pour a wine glass or so of sherry over the layers and chill well.

2

Crêpes, approximately Suzette, are the amateur gourmet’s delight, and more elaborately sogged pancakes have been paddled about in more horrendous combinations of butter, fruit juices, and ill-assorted liqueurs in the name of gastronomy than it is well to think on.

A good solution to this urge to stand up at the end of a meal and flourish forks over a specially constructed chafing dish is to introduce local Amphytrions to some such simple elegance as the following, a recipe that was handed out free, fifteen years ago in France, by the company that made Grand Marnier:

Dissolve 3 lumps of sugar in 1 teaspoon of water. Add the zest of an orange, sweet butter the size of a walnut, and a liqueur glass of Grand Marnier. Heat quickly, pour over hot, rolled crêpes, set aflame, and serve.

3

The following dish has almost the same simplicity as the preceding ones, but where they are excellent, this is, to my mind, purely horrible.

It is based on a packaged gelatin mixture which is almost a staple food in America. To be at its worst, which is easy, this should be pink, with imitation and also packaged whipped milk on top. To maintain this gastronomical level, it should be served in ‘salad’ form, a small quivering slab upon a wilted lettuce leaf, with some such boiled dressing as the one made from the rule my maternal grandmother handed down to me, written in her elegantly spiderish script.

I can think of no pressure strong enough to force me to disclose, professionally, her horrid and austere receipt. Suffice it to say that it succeeds in producing, infallibly, a kind of sour, pale custard, blandly heightened by stingy pinches of mustard and salt, and made palatable to the most senile tongues by large amounts of sugar and flour and good water. Grandmother had little truck with foreign luxuries like olive oil, and while she thought nothing of having the cook make a twelve-egg cake every Saturday, she could not bring herself to use more than the required one egg in any such frippery as a salad dressing. The truth probably is that salads themselves were suspect in her culinary pattern, a grudging concession to the Modern Age.

B is for Bachelors

… and the wonderful dinners they pull out of their cupboards with such dining-room aplomb and kitchen chaos.

Their approach to gastronomy is basically sexual, since few of them under seventy-nine will bother to produce a good meal unless it is for a pretty woman. Few of them at any age will consciously ponder on the aphrodisiac qualities of the dishes they serve forth, but subconsciously they use what tricks they have to make their little banquets, whether intimate or merely convivial, lead as subtly as possible to the hoped-for bedding down.

Soft lights, plenty of tipples (from champagne to straight rye), and if possible a little music, are the timeworn props in any such entertainment, on no matter what financial level the host is operating. Some men head for the back booth at the corner pub and play the jukebox, with overtones of medium-rare steak and French-fried potatoes. Others are forced to fall back on the soft-footed alcoholic ministrations of a Filipino houseboy, muted Stan Kenton on the super-Capeheart, and a little supper beginning with caviar malossol on ice and ending with a soufflé au kirschwasser d’Alsace.

The bachelors I’m considering at this moment are at neither end of the gastronomical scale. They are the men between twenty-five and fifty who if they have been married are temporarily out of it and are therefore triply conscious of both their heaven-sent freedom and their domestic clumsiness. They are in the middle brackets, financially if not emotionally. They have been around and know the niceties or amenities or whatever they choose to call the tricks of a well-set table and a well-poured glass, and yet they have neither the tastes nor the pocketbooks to indulge in signing endless chits at Mike Romanoff’s or ‘21’.

In other words, they like to give a little dinner now and again in the far from circumspect intimacy of their apartments, which more often than not consist of a studio-living-room with either a disguised let-down bed or a tiny bedroom, a bath, and a stuffy closet called the kitchen.

I have eaten many meals prepared and served in such surroundings. I am perhaps fortunate to be able to say that I have always enjoyed them – and perhaps even more fortunate to be able to say that I enjoyed them because of my acquired knowledge of the basic rules of seduction. I assumed that I had been invited for either a direct or an indirect approach. I judged as best I could which one was being contemplated, let my host know of my own foreknowledge, and then sat back to have as much pleasure as possible.

I almost always found that since my host knew I was aware of the situation, he was more relaxed and philosophical about its very improbable outcome and could listen to the phonograph records and savour his cautiously concocted Martini with more inner calm. And I almost always ate and drank well, finding that any man who knows that a woman will behave in her cups, whether of consommé double or of double Scotch, is resigned happily to a good dinner; in fact, given the choice between it and a rousing tumble in the hay, he will inevitably choose the first, being convinced that the latter can perforce be found elsewhere.

The drinks offered to me were easy ones, dictated by my statements made early in the game (I never bothered to hint but always said plainly, in self-protection, that I liked very dry Gibsons with good ale to follow, or dry sherry with good wine: safe but happy, that was my motto). I was given some beautiful liquids: really old Scotch, Swiss Dézelay light as mountain water, proud vintage Burgundies, countless bottles of champagne, all good too, and what fine cognacs! Only once did a professional bachelor ever offer me a glass of sweet liqueur. I never saw him again, feeling that his perceptions were too dull for me to exhaust myself, if after even the short time needed to win my acceptance of his dinner invitation he had not guessed my tastes that far.

The dishes I have eaten at such tables-for-two range from homegrown snails in home-made butter to pompano flown in from the Gulf of Mexico with slivered macadamias from Maui – or is it Oahu? I have found that most bachelors like the exotic, at least culinarily speaking: they would rather fuss around with a complex recipe for Le Hochepot de Queue de Boeuf than with a simple one called Stewed Ox-tail, even if both come from André Simon’s Concise Encyclopaedia of Gastronomy.1

They are snobs in that they prefer to keep Escoffier on the front of the shelf and hide Mrs Kander’s Settlement Cook Book.

They are experts at the casual: they may quit the office early and make a murderous sacrifice of pay, but when you arrive the apartment is pleasantly odorous, glasses and a perfectly frosted shaker or a bottle await you. Your host looks not even faintly harried or stovebound. His upper lip is unbedewed and his eye is flatteringly wolfish.

Tact and honest common sense forbid any woman’s penetrating with mistaken kindliness into the kitchen: motherliness is unthinkable in such a situation, and romance would wither on the culinary threshold and be buried forever beneath its confusion of used pots and spoons.

Instead the time has come for ancient and always interesting blandishments, of course in proper proportions. The Bachelor Spirit unfolds like a hungry sea anemone. The possible object of his affections feels cosily desired. The drink is good. He pops discreetly in and out of his gastronomical workshop, where he brews his sly receipts, his digestive attacks upon the fortress of her virtue. She represses her natural curiosity, and if she is at all experienced in such wars she knows fairly well that she will have a patterned meal which has already been indicated by his ordering in restaurants. More often than not it will be some kind of chicken, elaborately disguised with everything from Australian pine-nuts to herbs grown by the landlady’s daughter.

One highly expert bachelor-cook in my immediate circle swears by a recipe for breasts of young chicken, poached that morning or the night before, and covered with a dramatic and very lemony sauce made at the last minute in a chafing dish. This combines all the tricks of seeming nonchalance, carefully casual presentation, and attention-getting.

With it he serves chilled asparagus tips in his own version of vinaigrette sauce and little hot rolls. For dessert he has what is also his own version of riz à l’Impératrice, which he is convinced all women love because he himself secretly dotes on it – and it can be made the day before, though not too successfully.

This meal lends itself almost treacherously to the wiles of alcohol: anything from a light lager to a Moët et Chandon of a great year is beautiful with it, and can be well bolstered with the preprandial drinks which any bachelor doles out with at least one ear on the Shakespearean dictum that they may double desire and halve the pursuit thereof.

The most successful bachelor dinner I was ever plied with, or perhaps it would be more genteel to say served, was also thoroughly horrible.