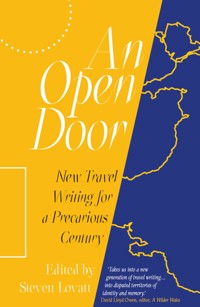

An Open Door E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'If the mountains secluded Wales from England, the long coastline was like an open door to the world at large.' – Jan Morris The history of Wales as a destination and confection of English Romantic writers is well-known, but this book reverses the process, turning a Welsh gaze on the rest of the world. This shift is timely: the severing of Britain from the European Union asks questions of Wales about its relationship to its own past, to the British state, to Europe and beyond, while the present political, public health and environmental crises mean that travel writing can and should never again be the comfortably escapist genre that it was. Our modern anxieties over identity are registered here in writing that questions in a personal, visceral way the meaning of belonging and homecoming, and reflects a search for stability and solace as much as a desire for adventure. Here are lyrical stories refracted through kaleidoscopes of family and world history, alongside accounts of forced displacement and the tenacious love that exists between people and places. Yet these pieces also show the enduring value and joy of travel itself. As Eluned Gramich expresses it 'It's one of the pleasures of travel to submit yourself to other people, let yourself be guided and taught'. Taken together, the stories of An Open Door extend Jan Morris' legacy into a turbulent present and even more uncertain future. Whether seen from Llŷn or the Somali desert, we still take turns to look out at the same stars, and it might be this recognition, above all, that encourages us to hold the door open for as long as we can. Featuring contributions from Eluned Gramich, Grace Quantock, Faisal Ali, Sophie Buchaillard, Giancarlo Gemin, Siân Melangell Dafydd, Mary-Ann Constantine, Kandace Siobhan Walker, Neil Gower, Julie Brominicks and Electra Rhodes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 235

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

About Steven Lovatt

Title Page

Introduction

ELUNED GRAMICH Carioca Cymreig

GRACE QUANTOCK Gone to Abergavenny

FAISAL ALI From the Desert to the Docks and Back

SOPHIE BUCHAILLARD Revolving Doors

GIANCARLO GEMIN The Valleys of Venice: Memories of an Italian immigrant in Wales

SIÂN MELANGELL DAFYDD Son of a Yew Tree

MARY-ANN CONSTANTINE King Stevan’s Roads

KANDACE SIOBHAN WALKER Clearances

NEIL GOWER From Light and Language and Tides

JULIE BROMINICKS The Murmuration

E. E. Rhodes All Among the Saints

Biographies

Parthian Non-Fiction

Copyright

Steven Lovattis the author ofBirdsong in a Time of Silence (Particular Books, 2021), and over the last decade his critical articles on Welsh literature, particularly Dorothy Edwards, have been published inNew Welsh Review,Planet,Critical Survey, the AWWE Yearbook and theLiterary Encyclopaedia. He reviews poetry forThe Friday Poem, teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Bristol, and copy-edits books on ethnography and philosophy from his home in Swansea.

An Open Door:

New Travel Writing for

a Precarious Century

Edited by Steven Lovatt

Introduction

‘Strange time to put together a travel book’, said a friend, and there was no need to ask what she meant. In this early spring of 2022, the Covid-19 pandemic that emerged two years ago is still complicating travel to an extent barely fathomable to we Western post-war generations who had taken its possibility for granted. Amid the hardships and annoyances of separation from family members, postponed journeys and the reluctant acceptance of video ‘meetings’, the Covid-prompted necessity to rethink how and why we travel, and whether we should really do so as blithely as we once did, has coincided with other, interconnected and equally pressing emergencies.

Prior to the mid-twentieth century, leisured travel was largely the preserve of a wealthy elite, and it could easily become so again, even as the combined disasters of climate collapse, pandemic and persecution are displacing millions of people on journeys that they would never have wished for. The dream of global interconnectedness on free market terms exposes its contradictions at the moment of its greatest fulfilment.

The title of this anthology is borrowed from Jan Morris, who wrote that to Owain Glyndŵr ‘if the mountains secluded Wales from England, the long coastline was like an open door to the world at large’. It was a strong and sudden sense of cultural loss and disorientation, prompted by the passing of Morris, which made me conceive the book as a sort of affirmation, and the image of an open door seems apt to contain all of the realities and possibilities that confront Wales in these dangerous times, from the door held open to refugees from Afghanistan to the Welsh government’s proposals to dissuade its young people from seeking ‘better prospects’ beyond the country, and calls to defend Welsh identity from a new movement of monied incomers. All this in a context – not alien to Glyndŵr – of rising calls for self-determination and the recent sealing, unprecedented for centuries, of the Welsh–English border, albeit this time as a measure against the spread of Covid-19.

In light of all this, an anthology of travel and place writing seems, at second glance, perfectly timed. Indeed, from another angle it is long overdue, since to my knowledge, despite Wales having for centuries been writtenabout, primarily as a sort of dream theatre for English aesthetes and capitalists, never before have Welsh and Wales-based authors been invited to ‘write back’ about their experiences as travellers within and beyond the country.An Open Door is also most likely one of the first travel anthologies in any language to have been published since the start of the pandemic and, notwithstanding the fully realised individuality of its stories, the distinctive anxieties of our age are everywhere apparent in what amounts in sum to a belated sea-change in the genre of travel writing itself.

This change is similar to those that have recently given new life to the closely related genre of nature writing. Historically, nature writing tended to overlook the historical and cultural specifics, the experiences and daily lives, of those who actually inhabit ‘nature’, while its exclusivity, related to a persistent privileging of the male ‘expert’, denied a voice to people – disproportionately women, children, the elderly and the otherwise culturally marginalised – who either hadn’t the opportunity to roam and write at leisure or whose perspectives were simply not valued.

On a parallel track, it isn’t all that difficult to see Wales as having been historically over-represented (and thusmisrepresented) by more or less voyeuristic and exoticising writers from elsewhere, nor to appreciate, as a consequence, the appropriateness of a Welsh challenge to what in travel writing, as in nature writing, is a Sunday-supplement-friendly hegemony of the soothing, ‘uplifting’ and unexceptional.An Open Door can certainly be interpreted as a challenge to this hegemony, and its contributors as representing, in the diversity of their backgrounds and experiences, a new and vitally necessary realism in the genre.

In 2022 we are quite obviously in all sorts of specific and unprecedented trouble, and this is directly acknowledged by almost all of this book’s stories. In Sophie Buchaillard’s ‘Revolving Doors’, the face coverings that she and her son are obliged to wear on public transport find an apocalyptic echo in famous Parisian landmarks screened behind scaffolding and other concealments: ‘Everywhere, tourists marvel at the audio description of buildings hidden behind plastic sheets. It is as if we are too late’. The sense of civilisation at bay is also present in references to social violence and terrorism in Brazil and Somalia, while in Mary-Ann Constantine’s ‘King Stevan’s Roads’, a story about how history adds layers to our sense of place also ends (or rather breaks off) in a Paris under siege.

Everywhere in the anthology, personal stories are given weight and depth by an awareness of history and politics, from the grim carceral tradition of British asylums to the enriching cultural hybridity made possible, for example, by the National Coal Board’s post-war recruitment drive in Italy, as revealed by Giancarlo Gemin’s moving memoir of his mother. Faisal Ali’s ‘From the Desert to the Docks and Back’ traces a narrative across four generations of the author’s family, providing glimpses along the way of almost two centuries of personal, national and global history, while in ‘Clearances’, Kandace Siobhan Walker witnesses at first hand both the effects of forced displacement and the tenacious love that exists between people and their ancestral homelands.

The collection extends individual experience in other ways, too. It is striking how many of these stories feature children and, more broadly, intergenerational relationships, and it is made clear how love of one’s places, whether native or adopted, implies guardianship and what Alan Garner has called ‘the subtle matter of owning and being owned’ by one’s landscapes, cities, religions and cultures. In ‘Gone to Abergavenny’, Grace Quantock finds solace in a place to which, as she is all too well aware, she would once have been forcibly confined, and for Siân Melangell Dafydd, the lived history of her family in a particular sacred landscape affords sanctuary for both herself and the next generation.

But for all the awareness, displayed throughout this anthology, of the weight of history we carry within ourselves, and which can’t help but inflect our perceptions, our assessments and our stories,An Open Door is no less a showcase of its contributors’ individual personalities in all their insightfulness and irony, eccentricities and humour. We learn a lot about the experience of travel itself. Several of the stories touch on the sheer awkwardness of being a stranger in a strange land, but also how this needn’t at all contradict a deep appreciation, both of the unfamiliar place itself and of how exposure to it can disarm us in ways both frightening and delightful. As Eluned Gramich expresses it in ‘Carioca Cymreig’, ‘It’s one of the pleasures of travel to submit yourself to other people, to let yourself be guided and taught’, while in ‘The Murmuration’, Julie Brominicks’ acknowledgement of her loneliness as a foreigner gives way movingly and with great psychological truth to sudden and unexpected confessions of ‘love [for] this place, and these people’.

A less apparent, though equally present, insight of this book is that the relationship between people and places is two-way: that is to say, in order to thrive, places also need their people. In ‘From Light and Language and Tides’, Neil Gower charts, literally as well as figuratively, a journey that begins with a professional interest in a poet’s attachment to his landscape and ends with a series of personal revelations about the different ways in which fidelities of all kinds are grounded in a relationship with inherited and discovered places. Similar questions about how journeys are bound up with loyalty and duty are explored in E. E. Rhodes’ ‘All Among the Saints’, which is also one of several pieces that demonstrate with wit, honesty and compassion how travel to even relatively nearby destinations can nevertheless involve the work of a lifetime.

Taken together, the stories ofAn Open Door extend Jan Morris’ legacy into a turbulent present and an even more uncertain future. In doing so, and by the sheer intellectual entertainment they provide, they not only irrigate Welsh literary culture, but affirm all cultures and individuals that still value the curiosity and humility proper to travel, and the deepening of one’s relationships with places and their inhabitants. Whether seen from Llŷn or the Somali desert, we still take turns to look out at the same stars, and it might be this recognition, above all, that encourages us to hold the door open for at least a while longer yet.

Steven Lovatt, 6 January 2022

ELUNED GRAMICH

Carioca Cymreig

Santa Teresa, Rio de Janeiro

New Year’s Eve 2018

It was the first time we saw the New Year in together. We stood on a balcony overlooking the city and the favela Santa Marta below: a wild garden ran down into small white buildings, bare bricks, a thousand electric lights. Rio’s outline bloomed with fireworks, and we watched the sparkling nets raining on the city. I remembered how in Welsh we saytân gwyllt, ‘wild fire’, for these marvels, and in Japan they sayhanabi, ‘fire flowers’, and I was reminded of how beautiful fireworks can be, but also of their power to lift us out of the grooves of our ordinary experiences.

‘Can you hear that?’ R said to me. He was smiling in the excitable way that means he is about to teach me something. ‘Thattak-tak-tak sound?’

‘You mean the fireworks.’

He shook his head. ‘No! It’s guns from the favela. The drug cartels are shooting into the air to celebrate.’

I backed away, immediately thinking of those stories I’d been told. The one about the cleaner at R’s university who was shot by a stray bullet while working on the campus. Or the story of the woman sitting up in bed with her partner, looking at her phone, when she was shot in the head by accident.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘It’s safe here.’

I turned to see R’s friends sitting around a platter of white chocolatebrigadeiros, drinking cold beer out of small glasses. The stories faded from my mind. This often happened to me in Rio: I had the luxury of forgetting, of turning away from violence and politics to watch fireworks from a balcony, taste the coconut anddoce de leite, accept the sparkler that was handed to me and with which I spelled our names in the air.

I also had the luxury of ignorance. It’s one of the pleasures of travel to submit yourself to other people, to let yourself be guided and taught. Usually, you’re expected to play the adult in life, but as a visitor with only a basic grasp of Portuguese, nothing was expected of me except perhaps politeness and patience. I didn’t even know how to celebrate New Year’s Eve properly. I’d brought a black dress decorated with colourful flowers with me from west Wales. Wearing black, I was quickly told, is unlucky. My mother-in-law – a woman half my size – cajoled me into wearing her clothes for the night: a long white skirt and a gold, glittering top that barely fitted. Earlier that day she’d forced a tiny camisole over my head. I got completely stuck, the nylon gluing to my hot, sweaty skin, and it was only with great effort that she managed to prise it over my shoulders. Camisole or not, I adhered to tradition. The colour you wear on New Year’s Eve represents your hopes for the coming year: yellow or gold for money, white for peace, red for passion, green for health and orange for happiness. (A year later, when R and I marry in Cardiff, I will forget to tell the Brazilians that black is unlucky for weddings in Wales. Our wedding photos show one side of the family in bright summer frocks, and the other side in black suits and cocktail dresses).

I sat down with R’s friends, joining the row of white and gold, and tried to follow their quick Portuguese while the machine guns from Santa Marta fired into the night sky.

***

Barra, Rio de Janeiro

18–21 December 2018

Deixe-me ir

Let me go

preciso andar

I must wander

Vou por aí a procurar

I’ll go around searching

rir pra não chorar

Laugh so I won’t cry

Deixe-me ir

Let me go

preciso andar

I must wander

Vou por aí a procurar

I’ll go around searching

rir pra não chorar

Laugh so I won’t cry

Cartola –‘Preciso me encontrar’

I suppose this is a practical kind of love story. The story of how things were going to work for R and I, between Aberystwyth and Rio de Janeiro. When you marry outside your nationality, you are bound not only to the person but also to their culture. It becomes part of your life. My Welsh mother married my German father and, I think, she didn’t know then that this would mean spending the rest of her life travelling to and from Munich, celebrating Christmas on Christmas Eve, learning and unlearning German on an annual cycle, hearing my father’s never-ending complaints about British bread. And so, when I fell in love with R, I absorbed the stories of his life and also the stories of his country, the Carioca stories – Carioca being the term for someone from Rio de Janeiro.

In our first weeks together, I had Chico Buarque, Cartola, Nelson Goncalves playing repeatedly on my phone: those old samba men of Brazilian song, crooning into my ears as I walked the Aberystwyth promenade. I didn’t understand a word of their lyrics. I assumed anything they sang was heart-rendingly romantic (and not, as it later transpired, intensely political). I paused my own studies to read a multi-volume history of Brazil while sitting on a bench at Aber marina, looking across at the blue-and-green fishing vessels coming in from Cardigan Bay, dreaming of how I would soon be exchanging Tan-y-Bwlch for Copacabana. I read Machado de Assis while staying with my parents that final Christmas without R: the surrealThe Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas, which made no sense to me at all at the time, as a political satire of nineteenth-century Brazilian society, and was hardly romantic, but which nevertheless made me feel closer to him.

It finally happened in December 2018: my first visit to Brazil to meet R’s family provided a warm, blue-skied view of my future. Here were the people I would meet year in and year out; here was the language I would listen to every day, either in person or on a WhatsApp call; here was the food that would be kept in the kitchen for the rest of my life, and the Brazilian shops I would be searching out (Where can you buyfeijão preto in Wales? And what about fresh cassava root? Is there no dendé oil in this country?) We were on the plane and then we were in São Paulo, in a very long queue for our connecting flight, holding two over-priced cartons ofpao de queijo. And I was terribly sick.

‘You gave me this,’ I said. R had been ill just before the flight. I ran around the enormous, chaotic airport, looking for a pharmacy. Where was Boots? ‘I can’t believe you gave me your cold. I hate you.’

‘I can’t believe you spent seventy reias onpão de queijo,’ he replied. ‘Do you know how much seventy reias is in pounds?’

I stuck another greasy ball of cheese bread into my mouth. ‘I could do with about a hundred more of them.’

We arrived late in Rio. R’s father picked us up and I sat in the back, eyes half-closed, pain tightening around my head, hoping no one would speak to me. I had met his parents once before when they visited Aberystwyth during Easter; but that had been different, taking them around a place I knew well. Here, I would be the one to submit, listen, follow in half-understanding.

My father-in-law is the same height as R, silver-haired, stocky, immaculately dressed. For him, everything must always be clean. The car is spotless. He has two showers a day, at least. R takes after his mother’s Lebanese side, having a mop of black curls and dark brown eyes, while his father is fairer, more Italianate. He doesn’t speak very much English, but he will speak to me anyway. He will say my name followed by one English word – ‘you’, say, or ‘today’ – and then he will um and ah because he has forgotten what words should follow the first word. Then he slips back into Portuguese, smiling, and pretending that I understand, and I pretend I understand too. Sometimes I do, but whether we understand each other or not is quite unimportant. This is something that people learning a foreign language may not realise: it doesn’t matter if you understand, or if you make yourself understood. It’s the effort to speak and understand that counts the most. Showing the other person that you would like to communicate with them, even if means utterly embarrassing yourself in the process, is the highest expression of kindness and affection. And so every time my father-in-law says, ‘Eluned, you, today, um, ah…,’ I like him more.

‘Eluned, you okay?Tudo bem?’

‘Tudo.Obrigada.’ ‘Fine, thank you’, although I felt like I was dying. I closed my eyes, listened to the calming hum of the air conditioner. I so wanted to make a good impression! To look nice for the family. R’s relatives are all so beautiful. Some of them are actual models! My nose throbbed, bright red.

The sun was sinking slowly. On either side of the road was a sprawl of low houses and, beyond the houses, the Atlantic Ocean, melting into the horizon. The yellow-pink of the sunset reflected in the water.

And then Barra – the Miami of Rio de Janeiro. We passed Barra Shopping (the biggest shopping centre in Latin America!), lines of palm trees, huge roads with no pavements. The architecture of the middle-classes in Rio is tall white apartment blocks, crowded together into neighbourhoods that share a local supermarket, parks, a swimming pool and, most importantly, security. These are gated areas where it is forbidden to hang your washing out to dry because it would look too much like a favela, or so I was told. Many apartments are unoccupied for most of the day, populated only by maids who clean and cook and change the sheets. Layers of security slowed our journey: guards in square outhouses, like a border check, glanced at R’s father’s identity card. Later, I had to go to the offices in R’s apartment complex to obtain a special visitor card, so that I would be able to wander the complex freely and use the swimming pool outside their building that R and his parents had never used themselves.

The apartment was white and incredibly clean: sharp lines, glass furniture, the tiled floors gleaming; living room, two bedrooms, balcony, kitchen and, behind the kitchen, a small room where theempregada, or housemaid, lived from Monday to Friday. R’s room had been cleared of most of his teenage accoutrements – only a few items remained to reflect his eccentric interest in English history, including a framed copy of the Magna Carta on the wall and a newspaper print headlining the start of the Second World War. The room was small and cool; there was a single bed with white sheets on which I immediately curled up, hoping the paracetamol would kick in. Even in my head-cold state, the perfect cleanliness of the apartment awed me –ironed sheets! – and made me think of the inexorable labour that underpinned it. A woman had done this for me and R: a woman I didn’t know had cleaned, ironed, folded and ordered all of R’s clothes. She had swept the dust from his empty desk, the tops of his books.

‘What’s her name again? Your maid?’

‘Irene. She’s not a maid,’ R said, pulling a clean shirt over his head. ‘Well, I suppose, she is and she isn’t. I call her my second mother. She looked after me while my parents worked. I used to “help” her clean the apartment when I was a toddler. You’ll meet her on Monday.’

‘Where does she live when she’s not here?’

‘Realengo. It’s an area outside the city. It’s normal for the help to live out in the suburbs and travel in for the week. Or they commute for hours every day on buses. They get up at five and arrive home at eleven.’ He stuck his wallet in his back pocket. ‘Remember, you can talk about anything but politics with my family. Don’t mention Bolsonaro.’

I rolled onto my back, stared up at the ceiling. ‘Can I stay here?’

‘Are you sure? I mean, that’s fine, but my aunt and uncle are expecting you.’

My head and face ached; a tissue was scrunched up in both hands. ‘No. I’ll come.’

***

R’s aunt lived in a gated complex too. We took the lift up to the flat where the whole family were eating and drinking (not thewhole family, I was later informed, but a small sub-section of it): R’s brother, sister-in-law, two cousins and their partners, and five-year-old twin girls with their hair in bunches. Everybody embraced and kissed me, even though I was obviously sick and spent most of the evening going back and forth to the toilet for more tissues. His aunt ushered me into the kitchen to show me her handmade gnocchi and I did my best not to sneeze on anything. The food was served on enormous silver platters, and R’s sister-in-law, an acclaimed chef, ate the food slowly and deliberately, as though we were sampling a tasting menu in a high-end restaurant. R piled the food high on his plate and asked me what I thought of it – wasn’t his aunt the best cook in the world? He was excited – smiling and laughing at everything, accepting one whisky after another from his equally cheerful uncle. It had been a year since he’d seen them; it made me happy to see him so animated and confident after a year of negotiating the world in his second language.

Meeting your partner’s family when you don’t share a common language is a gift, especially if you’re an introvert. You don’t need to make conversation; your role is to smile and eat and compliment the food. You can pass a pleasant half an hour together simply by asking what the words are for the food you have been given and repeating them wrongly. Language is replaced with touch – especially in Brazil, where hugs and kisses for greeting are the norm. I ate the gnocchi and the dessert ofgoiabada, a paste of guava and sugar, and said it was delicious, and smiled as best I could, and waited patiently for the conversations (and the whiskies) to come to an end.

R’s brother and sister-in-law drove us back. On going up another steep road, his brother turned and said to me: ‘Just look at these hilly streets! I bet you don’t have hills like this in Wales.’

***

There’s a certain zeal that comes with showing someone around your country, your city. The longer I played the tourist, the more my foreignness expanded and intensified. For R’s family I quickly transformed into a person who didn’t know very much about anything, because I hadn’t experienced the world through Brazil. I didn’t know about hills, for instance. Or fish (‘This is bacalhau– cod. Have you had cod before?’). Or beaches. Or healthcare. If I’d been younger, I would have found this infuriating, but I’ve learned that the impulse behind such enthusiastic tour-guiding is kind. These comments came from the sincere desire to include me in the culture, and the understandable desire to hear praise and love for that culture, too: love I was only too happy to give as we walked through the city, me taking notes on my phone as I went. I loved, for example, the wall at Urca, waist-high and built of stone, that skims the Baia de Guanabara, where people gather at dusk to watch the sunset, drink cold beer and watch the fishing boats sail in and out. I loved the Rio mountains that emerge impossibly from the centre of the city, like green thumbs erupting through the dull colours of the residential districts. And I loved Cristo Redentor’s silvery form against the sky.

We took the train to visit him. It was so hot, and the flight of steps that led to the foot of the statue so long, that I thought I would collapse. We stopped at the fruit juice stall so that I could drinkmamão, sweet pink-orange pulp in a glass, and then I tried, one by one, the rest of the juices I could not drink at home:caju andcupuaçu and avocado with milk, which was what R drank as a child like I drank banana-flavoured Nesquik. Later, I loved it when R’s friend draped a garland of plastic pouches around my body and ordered ‘Drink!’, which I did. I loved, also, the bowls of cold açai which we ate with long spoons. And in between the trains to the tops of the green thumbs, the too-blue ocean, the beaches and the beach-seller who said ‘Muchas Gracias!’ to me because I was foreign and they were the only foreign words I knew. I loved the coconut water and the meanders through the vast shopping centres where we bought our wedding rings. I heard all the stories of kidnap and theft and guns and they seemed nothing more than bad dreams.

‘It can’t happen here,’ I said.

And R replied, ‘You’re blind.’

***

R’s mother – a great believer in making life easier through purchase power – bought a tea Nespresso machine for my stay. Every morning I placed a capsule of green tea into the machine and watched it turn a simple ritual into something extremely complex. R made fun of his mother – ‘You know that’s the most expensive and ridiculous way of making tea, right?’ – but I quietly enjoyed the weirdness of preparing it this way. In the mornings, R’s mother would leave for work at the radiology clinic before seven, leaving R and I in the kitchen to have our breakfast with Irene, theempregada. His semi-retired father would come in, to say hello, hear our plans for the day or simply continue my education. ‘Did you know,’ he told me more than once, ‘that Portuguese is much harder than Spanish? We understand eighty per cent of what they say but they don’t understand eighty per cent of what we say!’

All the while, Irene made egg and tapioca for R. I couldn’t ask for one because I knew it entailed work, and so I preferred to eat pieces of yesterday’s ice-cream cake, or drink the glass of papaya and banana juice R’s father blended for me when he heard about that hot day on Cristo Redentor where themamão