1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

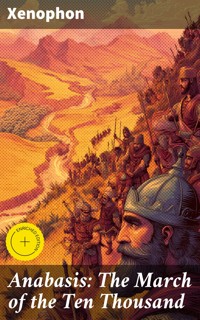

Xenophon's "Anabasis: The March of the Ten Thousand" is a remarkable historical narrative that recounts the harrowing journey of Greek mercenaries as they navigate their way home after a disastrous campaign in Persia. Written in a compelling, straightforward style, the text serves not only as a military account but also as a profound exploration of leadership, camaraderie, and the human spirit under duress. The work is often lauded for its vivid descriptions and insightful observations of both the landscape and the character of the diverse peoples encountered along the way, placing it within the broader context of classical historiography that combines personal experience with historical fact. Xenophon, a contemporary of Socrates and a student of philosophy, draws on his deep understanding of leadership and ethics to convey the lessons learned from the brutal realities of warfare and survival. His experiences as a soldier and eventual leader of the retreating forces inform the narrative, showcasing his ability to reflect on his own trials while providing a wider commentary on human behavior in crisis. His philosophical background enriches the text, intertwining practical insights with reflections on virtue and wisdom. "Anabasis" is not merely a historical document; it is an essential read for anyone interested in the complexities of human endurance and the intricacies of leadership. It resonates with contemporary themes of loyalty, exile, and the quest for home, making it a timeless exploration of the trials that shape both individuals and nations. This work is a vital addition to the libraries of historians, philosophers, and general readers alike. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Anabasis: The March of the Ten Thousand

Table of Contents

Introduction

Amid winter winds and shifting loyalties, a band of Greek soldiers finds itself deep within a vast empire, compelled to fight not for conquest but for the hard-won privilege of going home, while leadership is forged under duress and every choice weighs survival against honor.

Anabasis endures as a classic because it fuses eyewitness immediacy with disciplined narrative craft. Its clear, economical prose, long valued as a model of Attic style, supports a story that has shaped the literature of campaign memoir and the archetype of the hard retreat. Generations have read it as a study in collective resolve, practical reason, and the ethics of command. The work’s influence is visible even in antiquity, where its title resonated in historical writing, notably in Arrian’s account of Alexander. As both literature and source, it commands respect for balancing detail with drama, candor with restraint, and vivid action with reflective analysis.

Written by Xenophon, an Athenian soldier, statesman, and pupil of Socrates, Anabasis was composed in the fourth century BCE and relates a mercenary expedition that advances far inland under a Persian prince. When political fortunes turn and the army’s situation is upended, elected leaders and common soldiers must deliberate, adapt, and determine a path toward safety. The book presents the circumstances, councils, and practical measures through which a foreign force tries to sustain itself far from home. Without presuming omniscience, it offers a participant’s view of choices made under pressure and a lucid account of how a temporary community governs itself in crisis.

Xenophon writes with a dual purpose: to record events accurately and to illuminate the principles that allow a group to endure. He presents speeches, debates, and field decisions not as ornament but as a school of prudence. His vantage is distinctive, for he narrates in the third person even when describing his own actions, a technique that emphasizes the army’s collective character over individual display. Throughout, he attends to logistics, negotiation, morale, and discipline, the quiet foundations of success. The intention is not merely to enthrall, but to instruct readers in leadership under uncertainty, where deliberation, courage, and measure must guide action.

The narrative belongs to the pivotal era after the Peloponnesian War, when Greek soldiers increasingly hired their spears abroad and the Persian Empire’s vast resources intersected with Hellenic expertise. Anabasis makes that historical contact concrete: Greek hoplites, familiar with city-state politics, operate inside an imperial landscape of satraps, royal claims, and multilingual frontiers. The book reveals how conventions of the polis evolve when transplanted into a coalition force far from home. It also captures the Cold realities of late Classical warfare, where mobility, supplies, and bargaining count as much as battlefield valor, and where cultural encounter is a daily fact rather than a distant rumor.

As literature, Anabasis is notable for its clarity of arrangement and economy of style. Episodes move with a crisp rhythm from reconnaissance to council, from march to negotiation, from hardship to brief respite. Scenes are sketched with enough detail to orient the reader without halting momentum: distances, terrain, weather, and the temper of the troops all matter. Speeches frame choices, revealing character and contrasting counsels, while the narrative voice remains measured, even when danger presses. Xenophon repeatedly draws attention to forethought, cooperation, and the sober assessment of means, thereby transforming a perilous journey into a sustained meditation on order amidst contingency.

At its heart, the book studies how authority is earned and constrained when lives depend on mutual trust. It explores the tension between freedom and discipline, showing how lawfulness can arise from consent and how confidence in leaders is secured by service rather than rank. Themes of deliberation, responsibility, and shared identity recur, as do questions about when to negotiate and when to fight. The narrative considers fortune’s role but insists on preparation and self-command. By dramatizing how an army becomes a civic body, even temporarily, Anabasis invites reflection on community, the duties of leadership, and the virtues that allow groups to act as one.

Place itself becomes a protagonist. Mountains, rivers, snow, and scarcity test the army’s invention and resolve as surely as any hostile force. Moving through villages, passes, and borderlands, the Greeks meet peoples with unfamiliar customs and laws, and the story registers these encounters with sober curiosity. Geography is not mere backdrop; it shapes timelines, options, and morale. The demands of supply, the use of scouts, the role of interpreters, and the art of parley give the narrative a texture that is at once logistical and human. In charting a route through risk and difference, the book also charts the boundaries of perception and judgment.

For contemporary readers, Anabasis offers an absorbing combination of action, decision-making, and character under strain. It is a primer in leading small groups through shifting circumstances, a portrait of strategy that begins with honesty about constraints. The prose is accessible in translation, and its steady pace rewards close attention to how problems are framed and solved. Students of history and politics find a case study in legitimacy and consent, while travelers and adventurers encounter the perennial drama of wayfinding. The book’s moderation and sanity lend it a quiet authority, inviting readers to test their own instincts against its calm, practical intelligence.

The work’s influence extends across disciplines and centuries. Ancient readers drew on it for models of measured narrative and for insight into the conduct of campaigns, and its title later echoed in accounts of other long marches. Humanists and scholars in subsequent eras prized its style and used it in education to teach both language and judgment. Strategists and historians have mined it for lessons on cohesion, logistics, and civil-military relations. Writers of travel and survival narratives have found in it a durable pattern: not the conquest of lands, but the conquest of fear and confusion through deliberation, cooperation, and steady, purposeful movement.

Because it is both a literary work and a historical source, Anabasis has invited sustained commentary and fresh translation in every age. Readers debate its self-presentation and the balance it strikes between modesty and assertion, but agree on its exceptional lucidity and tact. The book’s openness to multiple readings—adventure, manual, memoir, ethnography—sustains its classroom life and its appeal to general audiences. Its sentences travel well, carrying a sense of proportion that tempers excitement with reflection. In an intellectual world fascinated by leadership and crisis, it remains a touchstone for how to write about action without surrendering to rhetoric or haste.

Anabasis speaks to enduring concerns: how communities preserve freedom, how leaders earn trust, how prudence and courage cooperate, and how human beings find direction when familiar structures fail. It evokes resilience without bravado and solidarity without sentimentality. Its lasting appeal lies in the marriage of clear thinking with vivid experience, offering readers an education in judgment carried by a compelling story. In an age that prizes agility and ethical clarity, Xenophon’s narrative remains timely, reminding us that survival is a civic art as much as a martial one, and that the way home is mapped by character as well as by terrain.

Synopsis

Anabasis, composed by Xenophon, recounts the expedition of roughly ten thousand Greek mercenaries recruited by Cyrus the Younger in 401 BCE to challenge his brother, the Persian king Artaxerxes II. The narrative begins with Cyrus gathering forces in Asia Minor, drawing contingents from various Greek city-states under experienced commanders. Xenophon, an Athenian, joins at the invitation of his friend Proxenus and later becomes a central eyewitness. The army’s composition, pay, and equipment are briefly described, and the political stakes are set: a dynastic contest within the Achaemenid Empire. With promises of rich rewards, the Greeks commit to a deep march into Persian territory.

The troops assemble at Sardis and move eastward, at first told they are to subdue troublesome tribes in Pisidia. As the route lengthens through Phrygia, Cilicia, and Syria, suspicions grow that the true objective lies far beyond. The army crosses the Cilician Gates, enters Tarsus, and proceeds along the Euphrates, joined by Persian contingents and supply trains. Xenophon notes the order of march, camp routine, and logistics needed to feed thousands in hostile lands. Skirmishes and negotiations with local governors test discipline. Despite uncertainty, pay and leadership keep the columns advancing toward the heart of the empire and a decisive encounter.

The climactic confrontation occurs near Cunaxa, north of Babylon, where Cyrus meets Artaxerxes with mixed Greek and Asiatic forces. The Greeks, positioned on one wing, drive back the troops opposing them, demonstrating the effectiveness of the hoplite phalanx against Persian levies. However, events elsewhere on the field determine the outcome. Cyrus falls in the attempt to unseat his brother, removing the commander who had hired and supplied the mercenaries. Although tactically successful on their front, the Greek soldiers find themselves deep inside Mesopotamia, without a patron, transport, or clear route home, and surrounded by a hostile imperial apparatus.

In the aftermath, the Persian satrap Tissaphernes opens negotiations, offering provisions and safe passage in exchange for withdrawal. The Greeks, maintaining a compact camp and daily marches, accept an uneasy truce while searching for a strategy. A parley leads to a sudden reversal: several leading generals, including Clearchus and Proxenus, are seized and executed under pretext. The army wakes to leaderless uncertainty, deprived of guides and facing constant surveillance by cavalry and archers. Panic threatens, but the soldiers convene assemblies, reaffirm their collective oath, and resolve to appoint new commanders from within their ranks to plan a secure retreat.

Xenophon, previously a junior participant, emerges as one of the newly chosen strategoi alongside Cheirisophus and others. He addresses the troops about order, vigilance, and self-reliance, and the leadership institutes reforms: restructured vanguards and rearguards, consistent scouting, night watches, and signals. The army adopts flexible tactics to counter mobility and missile fire, pairing heavy infantry with peltasts and slingers. They decide to march north toward friendly Greek cities on the Black Sea, seeking terrain that neutralizes enemy cavalry. Emphasis falls on cohesive columns, fortified camps, and the avoidance of ambush, with clear rules for foraging, discipline, and the division of spoils.

The retreat begins under near-constant harassment from Persian horsemen and archers shadowing the column. Xenophon records adaptations: sudden rushes by light troops to disrupt shooters, counter-marching to protect baggage, and the creation of small cavalry units from captured mounts. Rivers and canals pose hazards, prompting feints and bridgework. When routes along the Tigris prove blocked, the Greeks turn toward mountainous country to break pursuit. The narrative details marches measured by stades, the rotation of units under pressure, and the practicalities of keeping cohesion amid fatigue. The priority remains maintaining formation while procuring food through markets, requisition, and negotiated truces.

The traverse of the land of the Karduchoi presents one of the most difficult phases. Narrow paths, steep ravines, and hostile hill tribes force slow movement under constant skirmish. The Greeks improvise with ladders and shields to scale heights and protect retreats, while weather and terrain inflict losses. Beyond these passes, winter in Armenia brings snow, cold, and shortages. Guides are secured, sometimes by agreement, sometimes by compulsion, to find crossings and villages. Medical challenges, frostbite, and transport of the wounded are described succinctly. Despite hardships, steady command conferences and unit councils maintain morale and enforce shared decision-making.

Reaching the Black Sea coast marks a turning point, with access to Greek colonies such as Trapezus and Sinope offering markets, sanctuary, and ships. The army holds sacrifices and games, restocks, and debates next steps. Internal disputes arise over leadership, routes by land or sea, and relations with coastal communities. Some detachments sail while others march along the shore, encountering both assistance and resistance. The narrative records assemblies, fines, and oaths to restrain disorder. Envoys from Sparta and local powers appear, proposing employment. The mercenaries, still cohesive, look to reenter Greek political networks while preserving their autonomy and pay.

The account concludes with the force delivered from immediate peril and integrated, in stages, into campaigns led by Spartan commanders in Asia Minor. Xenophon closes by underscoring procedures that sustained the army: elected leadership, discipline in camp and march, pragmatic logistics, and tactical adaptability against cavalry and missile troops. Anabasis serves as a clear record of geography and peoples encountered, as well as a practical study of organized retreat under pressure. Its central message is the capacity of a self-governed body of soldiers to endure and navigate hostile conditions through collective deliberation, steady command, and the consistent application of drill.

Historical Context

The narrative of Anabasis unfolds between 401 and roughly 399 BCE across the vast Achaemenid Persian Empire and its periphery. The mercenary army begins near Sardis in Lydia, marches through Phrygia and Cilicia, crosses the Euphrates at Thapsacus into Upper Mesopotamia, and fights near Babylon at Cunaxa. The retreat arcs north through the Tigris basin, the highlands of the Carduchians and Armenia, and down to the Black Sea at Trapezus, Cerasus, and Sinope, before turning west to Byzantium and Thrace. The setting is the transitional moment between the Peloponnesian War and Spartan hegemony, when Greek military labor, Persian imperial politics, and interstate rivalry overlapped in western Asia Minor.

The time is marked by Artaxerxes II’s reign (404–359 BCE) and the satrapal administration that governed Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Tissaphernes in Lydia and Caria, and Pharnabazus in Hellespontine Phrygia, managed frontier politics with Greek cities. The King’s Road linked Sardis to Susa, enabling rapid imperial mobilization. On the Greek side, Athens had recently surrendered (404), while Sparta installed garrisons and boards of ten in allied cities. Ionian poleis remained a Persian sphere of influence contested by Sparta. The book’s geography, seasonal hardships, and the need for negotiated passage through satrapies and tribal territories reflect the lived realities of this imperial borderland in the early fourth century BCE.

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) reshaped the Greek world. After the Sicilian disaster (415–413), Athens relied on Aegean tribute and grain from the Black Sea, while Sparta leveraged Persian gold. In 407, Cyrus the Younger supported the Spartan admiral Lysander, funding the fleet that triumphed at Aegospotami (405), precipitating Athens’ surrender in 404. This war produced a generation of experienced hoplites and peltasts seeking pay. Anabasis mirrors this aftermath: the Ten Thousand include veterans from many poleis whose skills were redeployed on Persian soil. Xenophon’s account presupposes the tactical confidence of postwar Greek infantry and the economic incentives driving mercenary enlistment beyond the fractured polis system.

In 404–403 BCE, Athens endured the regime of the Thirty Tyrants, installed with Spartan backing, prompting purges, confiscations, and exile. Civil strife ended with the restoration of democracy in 403. These convulsions undermined civic cohesion and livelihoods, fostering recourse to foreign service. Although Xenophon was not himself a political exile at this time, the atmosphere of polarized oligarchic and democratic factions informs his sensitivity to leadership, discipline, and collective decision-making under stress. The book’s assemblies, debates, and elections of officers among the Ten Thousand echo the era’s contested authority structures and show how Greek soldiers adapted civic habits to military governance in unfamiliar, hostile environments.

Cyrus the Younger, son of Darius II and Parysatis, became satrap of Lydia, Phrygia, and Cappadocia around 407 BCE and commander in western Asia. Upon Darius II’s death in 404, his brother Artaxerxes II took the throne. Cyrus was arrested at Susa on suspicion of conspiracy, then released through Parysatis’s influence. Determined to claim the kingship, he covertly assembled forces, recruiting Greek mercenaries under pretexts of campaigning against Pisidian highlanders. Xenophon’s history turns on this dynastic contest: the expedition’s true aim was revealed only near the Euphrates, placing the Greeks at the center of a Persian succession crisis that highlights the vulnerabilities of Achaemenid rule.

Recruitment drew upon disparate Greek networks. Clearchus of Sparta, an exile turned general, led a disciplined contingent; Proxenus of Boeotia, Menon of Thessaly, Agias of Arcadia, and Socrates of Achaea commanded others. By the Cilician Gates, the Greeks numbered roughly 10,400 hoplites and about 2,500 peltasts and archers, plus noncombatants. Musters occurred at places such as Sardis and Issus; pay promises came via Cyrus’s agents. The march crossed the Euphrates at Thapsacus, a major ford. Anabasis documents muster rolls, pay disputes, and logistical arrangements, revealing a semi-professional military labor market in which personal patronage, contracts, and city rivalries funneled soldiers into transregional campaigns.

The Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BCE, fought north of Babylon along the canals of the lower Euphrates, decided the succession struggle. Artaxerxes II fielded a numerically overwhelming host with cavalry, scythed chariots, and contingents from many satrapies. Cyrus placed the Greeks on his right under Clearchus and advanced with his Asiatic troops in the center. The Greek phalanx routed the Persian left, but Cyrus’s impetuous charge at his brother ended with Cyrus killed in melee. Though tactically victorious, the Greeks were suddenly leaderless in a hostile empire whose political objective had evaporated. Xenophon’s narrative emphasizes hoplite cohesion against cavalry-heavy opponents, yet underlines strategy’s dependence on clear political ends.

After Cunaxa, Tissaphernes promised safe conduct but seized the initiative. At a parley near the Great Zab, he arrested the Greek generals Clearchus, Proxenus, Menon, Agias, and Socrates, and several captains; most were executed, Menon later after torture. The decapitation of command forced rapid institutional improvisation. Xenophon, previously a volunteer connected through Proxenus, was elected strategos alongside Cheirisophus and others. The episode dramatizes Persian court politics and the risks of negotiation without leverage. In Anabasis, the treachery catalyzes a transition from a client army serving a Persian prince to an autonomous body politic, illustrating how Greek military collegiality could regenerate leadership under existential pressure.

The northward retreat traversed forbidding terrain. The Ten Thousand fought through the Carduchians’ ravines, where archers and slingers harried hoplites from heights. Entering Armenia in winter, they confronted snow, frostbite, and hunger, skirmishing with local forces under satrap Tiribazus. Improvised tactics emerged: forming hollow squares, using captured guides, and adapting to missile warfare with screens of light troops. Near Mount Theches above Trapezus on the Black Sea, the soldiers famously cried Thalatta, Thalatta, the sea, signaling survival and potential resupply. Xenophon’s account conveys the strategic importance of topography, climate, and ethnography in Anatolia, and the capacity of disciplined infantry to endure attrition by flexible, locally attuned marching methods.

At the Black Sea in 400 BCE, the Greeks engaged with coastal poleis such as Trapezus, Cerasus, Cotyora, and Sinope, negotiating provisions, ships, and political support. Internal disputes over plunder, pay, and the route home tested cohesion. Moving west past Heraclea Pontica to Byzantium, they encountered Spartan harmosts and Persian influence in the Straits. Many later served the Thracian prince Seuthes II before being hired by the Spartan general Thibron for operations against Tissaphernes in Ionia (399). Anabasis connects the central plot to the geopolitical corridor linking the Euxine grain trade, the Hellespont, and Asia Minor, showing how Greek cities mediated mercenary transit and imperial rivalries.

The Achaemenid imperial structure relied on satraps, tribute, and royal roads. Western satrapies, especially Lydia and Hellespontine Phrygia, balanced warfare and diplomacy with Greek communities. Cavalry superiority, scythed chariots, and vast levies contrasted with the dense Greek phalanx. Court politics mattered: Parysatis’s interventions, eunuch advisors, and rivalries like Tissaphernes versus Pharnabazus shaped policy. The empire’s resilience rested on logistical depth and the ability to attrit invaders. By documenting negotiations with satraps, royal envoys, and local rulers, Anabasis provides a primary window into Persian administrative practice and military doctrine, revealing why a small, cohesive force could win battles yet struggle to translate tactical successes into strategic outcomes.

The growth of Greek mercenary service in the late fifth and early fourth centuries BCE was a social movement born of demographic pressure, war weariness, and economic need. Veterans from Peloponnesian War campaigns, Thracian peltasts, and archers from Crete sought steady pay abroad. Discipline was maintained through assemblies, oaths, and elected officers, while plunder supplemented wages. Anabasis is a unique record of this professionalization: the army’s deliberations over routes, pay arrears, and justice display a portable civic culture. The text shows how mercenary institutions could both reproduce Greek political norms and create new ones, enabling autonomous action far from the polis in perilous conditions.

Sparta’s hegemony after 404 BCE rested on garrisons, decarchies, and the diplomacy of leaders like Lysander. The city’s alignment with Cyrus during the late war complicated relations with Artaxerxes II. After 399, friction with Tissaphernes and Persian backing for anti-Spartan coalitions spurred Spartan expeditions to Asia. Agesilaus II crossed to Asia Minor in 396, campaigning in Phrygia and along the coast until recalled in 394. The Ten Thousand’s experience demonstrated Persian vulnerabilities inland and the operational reach of Greek infantry. Anabasis thus informs and reflects Spartan strategy: Xenophon later served Agesilaus and chronicled how lessons from the march influenced Spartan aims and propaganda.

The King’s Peace, or Peace of Antalcidas (387/386 BCE), imposed by the Persian court, recognized the autonomy of Greek poleis while ceding the cities of Asia Minor and Cyprus to Artaxerxes II. Sparta, as guarantor, gained leverage in Greece at the cost of Ionian freedom. This settlement institutionalized Persian arbitration of Greek affairs and underscored enduring imperial influence across the Aegean. Anabasis foreshadows this reality by revealing how Persian resources and diplomacy could shape Greek choices, even after battlefield setbacks. The work’s portrait of negotiation, tribute, and satrapal authority anticipates the logic that culminated in a peace dictated from Susa.

The Black Sea littoral, colonized by Milesian foundations like Sinope and its daughter Trapezus, sustained Greek economies with timber, slaves, and especially grain. Control of the Hellespont and Bosporus linked this trade to the Aegean, making the region strategically vital to Athens and Sparta. Local peoples, including the Mossynoeci, Chalybes, and Taochi, practiced distinctive warfare and customs. In Anabasis, the Ten Thousand’s interactions with these communities, and with cities seeking to balance hospitality with self-interest, record the ethnography and commercial ecology of the Euxine. The text captures how maritime provisioning and civic diplomacy determined survival and shaped regional politics in 400 BCE.

Xenophon of Athens (c. 430–354 BCE), a student of Socrates, embodied the era’s crossings between philosophy, soldiering, and politics. He joined the expedition through Proxenus of Boeotia and emerged as a leader after the generals’ seizure. Socrates’ execution in 399, while Xenophon was abroad or soon after his return, framed his attitudes toward civic fate and justice. For serving with Sparta under Agesilaus, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and settled at Scillus near Olympia under Spartan patronage. His proximity to Spartan policy and personal experience of Persian and Thracian theaters gave him the vantage to depict the geopolitical axes that Anabasis explores.

Anabasis functions as a political and social critique by exposing the fragility of imperial authority and the perils of Greek disunity. It contrasts the cohesion and deliberative resilience of citizen-soldiers with the treachery and opacity of court politics, while also documenting the mercenary economy’s moral hazards, from plunder to internecine quarrels. The narrative scrutinizes leadership, arguing for accountability, transparency, and tactical flexibility over autocratic fiat. It highlights class and status tensions within a mixed army and between Greeks and subject peoples. By situating survival within negotiated norms rather than brute force alone, the book implicitly indicts both Persian despotism and opportunistic Greek power politics.

Author Biography

Xenophon of Athens was an Athenian soldier, historian, and philosopher active from the late fifth to the mid-fourth century BCE. A student and admirer of Socrates, he combined firsthand military experience with reflective prose, producing works that range from campaign narrative and political history to Socratic dialogues and technical handbooks. His Anabasis, recounting the march of Greek mercenaries through Asia, became a classic of leadership and survival literature, while Hellenica extended the Greek historical record beyond Thucydides. Noted for a clear, practical Attic style, Xenophon’s writings offer a window onto war, governance, and everyday conduct in the classical Greek world.

Raised in classical Athens, Xenophon encountered Socrates as a young man and remained within the philosopher’s circle for years. That formative association shaped his ethical interests: self-control, usefulness, and the tested character of leaders recur throughout his works. He also absorbed the example of earlier historians, especially Herodotus and Thucydides, whose narrative methods and concern for causes informed his own practice. An accomplished horseman, he cultivated an interest in equestrian skills and military organization that later yielded specialized treatises. His prose favors economy and concrete detail rather than elaborate argument, aiming to instruct readers through persuasive examples and the observation of conduct.

In the early fourth century BCE, Xenophon joined the expedition of Cyrus the Younger, who sought to seize the Persian throne. After Cyrus fell in battle and the Greek generals were killed by treachery, the stranded army elected new leaders, among them Xenophon, who helped direct the long retreat north to the Black Sea. Anabasis narrates that journey in the third person, balancing vivid scenes with practical reflections on logistics, morale, and negotiation. The work provides rare information on the peoples and geographies of Anatolia and Mesopotamia, while also presenting a case study in improvised leadership under severe and shifting constraints.

Xenophon’s Hellenica continues the story where Thucydides breaks off, covering the closing phase of the Peloponnesian War and the turbulent decades that followed. Written from an eyewitness and contemporary perspective, it traces shifting alliances, Spartan hegemony, and recurrent civil strife through compact, often understated episodes. Readers have long debated its selectivity and perspective, noting his sympathy for Sparta and admiration for disciplined rule. That outlook also appears in Agesilaus, a laudatory portrait of the Spartan king, and in the Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, which describes Spartan institutions, their virtues, and their eventual decline when wealth and complacency undermined traditional training and norms.

Alongside history, Xenophon composed a substantial body of Socratic literature. Memorabilia defends Socrates’ character and method by assembling conversations that emphasize practical virtue over abstract metaphysics. His Apology offers an alternative account of Socrates’ trial, concise and sober in tone. The Symposium presents convivial dialogue on love and character, while Oeconomicus explores household management and civic usefulness through Socratic discourse with an Athenian gentleman and his household. In Hiero, a tyrant and a poet consider the burdens of power. Compared with Plato, Xenophon favors brevity, clear examples, and the moral education of citizens suited to leadership, domestic economy, and service.

His technical and advisory writings reflect the same practical bent. On Horsemanship and the Cavalry Commander set out training, equipment, and tactics for riders and officers. On Hunting praises disciplined sport as education for war and citizenship. In his later Ways and Means (Poroi), he proposes measures to stabilize Athenian revenues through better management and public resources. Xenophon’s own life intersected these concerns: after serving with Sparta in the early fourth century, he was exiled from Athens and settled for years at Scillus, near Olympia. Following political reversals that weakened Spartan control, he left Scillus and spent subsequent years elsewhere in Greece.

Xenophon’s later decades were productive, and he died in the mid-fourth century BCE. His works circulated widely in antiquity, valued for their clarity and utility; ancient readers treated the Anabasis as both history and a model of command. The Cyropaedia, a partly historical, partly didactic portrait of Cyrus the Great, influenced later discussions of rulership and education from classical to early modern times. Modern scholars continue to mine Hellenica for events and assess the biases shaping its narrative. Today, Xenophon is read for Greek prose style, for insight into Socratic ethics, and for enduring reflections on leadership, institutions, and practical action.

Anabasis: The March of the Ten Thousand

BOOK I

I

Darius and Parysatis had two sons: the elder was named Artaxerxes, and the younger Cyrus. Now, as Darius lay sick and felt that the end of life drew near, he wished both his sons to be with him. The elder, as it chanced, was already there, but Cyrus he must needs send for from the province over which he had made him satrap, having appointed him general moreover of all the forces that muster in the plain of the Castolus. Thus Cyrus went up, taking with him Tissaphernes as his friend, and accompanied also by a body of Hellenes, three hundred heavy armed men, under the command of Xenias the Parrhasian1.

Now when Darius was dead, and Artaxerxes was established in the kingdom, Tissaphernes brought slanderous accusations against Cyrus before his brother, the king, of harbouring designs against him. And Artaxerxes, listening to the words of Tissaphernes, laid hands upon Cyrus, desiring to put him to death; but his mother made intercession for him, and sent him back again in safety to his province. He then, having so escaped through peril and dishonour, fell to considering, not only how he might avoid ever again being in his brother's power, but how, if possible, he might become king in his stead. Parysatis, his mother, was his first resource; for she had more love for Cyrus than for Artaxerxes upon his throne. Moreover Cyrus's behaviour towards all who came to him from the king's court was such that, when he sent them away again, they were better friends to himself than to the king his brother. Nor did he neglect the barbarians in his own service; but trained them, at once to be capable as warriors and devoted adherents of himself. Lastly, he began collecting his Hellenic armament, but with the utmost secrecy, so that he might take the king as far as might be at unawares.

The manner in which he contrived the levying of the troops was as follows: First, he sent orders to the commandants of garrisons in the cities (so held by him), bidding them to get together as large a body of picked Peloponnesian troops as they severally were able, on the plea that Tissaphernes was plotting against their cities; and truly these cities of Ionia had originally belonged to Tissaphernes, being given to him by the king; but at this time, with the exception of Miletus, they had all revolted to Cyrus. In Miletus, Tissaphernes, having become aware of similar designs, had forestalled the conspirators by putting some to death and banishing the remainder. Cyrus, on his side, welcomed these fugitives, and having collected an army, laid siege to Miletus by sea and land, endeavouring to reinstate the exiles; and this gave him another pretext for collecting an armament. At the same time he sent to the king, and claimed, as being the king's brother, that these cities should be given to himself rather than that Tissaphernes should continue to govern them; and in furtherance of this end, the queen, his mother, co-operated with him, so that the king not only failed to see the design against himself, but concluded that Cyrus was spending his money on armaments in order to make war on Tissaphernes. Nor did it pain him greatly to see the two at war together, and the less so because Cyrus was careful to remit the tribute due to the king from the cities which belonged to Tissaphernes.

A third army was being collected for him in the Chersonese, over against Abydos, the origin of which was as follows: There was a Lacedaemonian exile, named Clearchus, with whom Cyrus had become associated. Cyrus admired the man, and made him a present of ten thousand darics2. Clearchus took the gold, and with the money raised an army, and using the Chersonese as his base of operations, set to work to fight the Thracians north of the Hellespont, in the interests of the Hellenes, and with such happy result that the Hellespontine cities, of their own accord, were eager to contribute funds for the support of his troops. In this way, again, an armament was being secretly maintained for Cyrus.

Then there was the Thessalian Aristippus, Cyrus's friend3, who, under pressure of the rival political party at home, had come to Cyrus and asked him for pay for two thousand mercenaries, to be continued for three months, which would enable him, he said, to gain the upper hand of his antagonists. Cyrus replied by presenting him with six months' pay for four thousand mercenaries—only stipulating that Aristippus should not come to terms with his antagonists without final consultation with himself. In this way he secured to himself the secret maintenance of a fourth armament.

Further, he bade Proxenus, a Boeotian, who was another friend, get together as many men as possible, and join him in an expedition which he meditated against the Pisidians 4, who were causing annoyance to his territory. Similarly two other friends, Sophaenetus the Stymphalian 5, and Socrates the Achaean, had orders to get together as many men as possible and come to him, since he was on the point of opening a campaign, along with Milesian exiles, against Tissaphernes. These orders were duly carried out by the officers in question.

1 Parrhasia, a district and town in the south-west of Arcadia.

3 Lit. "guest-friend." Aristippus was, as we learn from the "Meno" of Plato, a native of Larisa, of the family of the Aleuadae, and a pupil of Gorgias. He was also a lover of Menon, whom he appears to have sent on this expedition instead of himself.

4 Lit. "into the country of the Pisidians."

5 Of Stymphalus in Arcadia.

II

But when the right moment seemed to him to have come, at which he should begin his march into the interior, the pretext which he put forward was his desire to expel the Pisidians utterly out of the country; and he began collecting both his Asiatic and his Hellenic armaments, avowedly against that people. From Sardis in each direction his orders sped: to Clearchus, to join him there with the whole of his army; to Aristippus, to come to terms with those at home, and to despatch to him the troops in his employ; to Xenias the Arcadian, who was acting as general-in-chief of the foreign troops in the cities, to present himself with all the men available, excepting only those who were actually needed to garrison the citadels. He next summoned the troops at present engaged in the siege of Miletus, and called upon the exiles to follow him on his intended expedition, promising them that if he were successful in his object, he would not pause until he had reinstated them in their native city. To this invitation they hearkened gladly; they believed in him; and with their arms they presented themselves at Sardis. So, too, Xenias arrived at Sardis with the contingent from the cities, four thousand hoplites[1]; Proxenus, also, with fifteen hundred hoplites and five hundred light-armed troops; Sophaenetus the Stymphalian, with one thousand hoplites; Socrates the Achaean, with five hundred hoplites; while the Megarion Pasion came with three hundred hoplites and three hundred peltasts 1. This latter officer, as well as Socrates, belonged to the force engaged against Miletus. These all joined him at Sardis.

But Tissaphernes did not fail to note these proceedings. An equipment so large pointed to something more than an invasion of Pisidia: so he argued; and with what speed he might, he set off to the king, attended by about five hundred horse. The king, on his side, had no sooner heard from Tissaphernes of Cyrus's great armament, than he began to make counter-preparations.

Thus Cyrus, with the troops which I have named, set out from Sardis, and marched on and on through Lydia three stages, making two-and-twenty parasangs 2, to the river Maeander. That river is two hundred feet 3 broad, and was spanned by a bridge consisting of seven boats. Crossing it, he marched through Phrygia a single stage, of eight parasangs, to Colossae, an inhabited city 4, prosperous and large. Here he remained seven days, and was joined by Menon the Thessalian, who arrived with one thousand hoplites and five hundred peltasts, Dolopes, Aenianes, and Olynthians. From this place he marched three stages, twenty parasangs in all, to Celaenae, a populous city of Phrygia, large and prosperous. Here Cyrus owned a palace and a large park 5 full of wild beasts, which he used to hunt on horseback, whenever he wished to give himself or his horses exercise. Through the midst of the park flows the river Maeander, the sources of which are within the palace buildings, and it flows through the city of Celaenae. The great king also has a palace in Celaenae, a strong place, on the sources of another river, the Marsyas, at the foot of the acropolis. This river also flows through the city, discharging itself into the Maeander, and is five-and-twenty feet broad. Here is the place where Apollo is said to have flayed Marsyas, when he had conquered him in the contest of skill. He hung up the skin of the conquered man, in the cavern where the spring wells forth, and hence the name of the river, Marsyas. It was on this site that Xerxes, as tradition tells, built this very palace, as well as the citadel of Celaenae itself, on his retreat from Hellas, after he had lost the famous battle. Here Cyrus remained for thirty days, during which Clearchus the Lacedaemonian arrived with one thousand hoplites and eight hundred Thracian peltasts and two hundred Cretan archers. At the same time, also, came Sosis the Syracusian with three thousand hoplites, and Sophaenetus the Arcadian 6 with one thousand hoplites; and here Cyrus held a review, and numbered his Hellenes in the park, and found that they amounted in all to eleven thousand hoplites and about two thousand peltasts.

From this place he continued his march two stages—ten parasangs—to the populous city of Peltae, where he remained three days; while Xenias, the Arcadian, celebrated the Lycaea 7 with sacrifice, and instituted games. The prizes were headbands of gold; and Cyrus himself was a spectator of the contest. From this place the march was continued two stages—twelve parasangs—to Ceramon-agora, a populous city, the last on the confines of Mysia. Thence a march of three stages—thirty parasangs—brought him to Caystru-pedion 8, a populous city. Here Cyrus halted five days; and the soldiers, whose pay was now more than three months in arrear, came several times to the palace gates demanding their dues; while Cyrus put them off with fine words and expectations, but could not conceal his vexation, for it was not his fashion to stint payment, when he had the means. At this point Epyaxa, the wife of Syennesis, the king of the Cilicians, arrived on a visit to Cyrus; and it was said that Cyrus received a large gift of money from the queen. At this date, at any rate, Cyrus gave the army four months' pay. The queen was accompanied by a bodyguard of Cilicians and Aspendians; and, if report speaks truly, Cyrus had intimate relations with the queen.

From this place he marched two stages—ten parasangs—to Thymbrium, a populous city. Here, by the side of the road, is the spring of Midas, the king of Phrygia, as it is called, where Midas, as the story goes, caught the satyr by drugging the spring with wine. From this place he marched two stages—ten parasangs—to Tyriaeum, a populous city. Here he halted three days; and the Cilician queen, according to the popular account, begged Cyrus to exhibit his armament for her amusement. The latter being only too glad to make such an exhibition, held a review of the Hellenes and barbarians in the plain. He ordered the Hellenes to draw up their lines and post themselves in their customary battle order, each general marshalling his own battalion. Accordingly they drew up four-deep. The right was held by Menon and those with him; the left by Clearchus and his men; the centre by the remaining generals with theirs. Cyrus first inspected the barbarians, who marched past in troops of horses and companies of infantry. He then inspected the Hellenes; driving past them in his chariot, with the queen in her carriage. And they all had brass helmets and purple tunics, and greaves, and their shields uncovered 9.

After he had driven past the whole body, he drew up his chariot in front of the centre of the battle-line, and sent his interpreter Pigres to the generals of the Hellenes, with orders to present arms and to advance along the whole line. This order was repeated by the generals to their men; and at the sound of the bugle, with shields forward and spears in rest, they advanced to meet the enemy. The pace quickened, and with a shout the soldiers spontaneously fell into a run, making in the direction of the camp. Great was the panic of the barbarians. The Cilician queen in her carriage turned and fled; the sutlers in the marketing place left their wares and took to their heels; and the Hellenes meanwhile came into camp with a roar of laughter. What astounded the queen was the brilliancy and order of the armament; but Cyrus was pleased to see the terror inspired by the Hellenes in the hearts of the Asiatics[1q].

From this place he marched on three stages—twenty parasangs—to Iconium, the last city of Phrygia, where he remained three days. Thence he marched through Lycaonia five stages—thirty parasangs. This was hostile country, and he gave it over to the Hellenes to pillage. At this point Cyrus sent back the Cilician queen to her own country by the quickest route; and to escort her he sent the soldiers of Menon, and Menon himself. With the rest of the troops he continued his march through Cappadocia four stages—twenty-five parasangs—to Dana, a populous city, large and flourishing. Here they halted three days, within which interval Cyrus put to death, on a charge of conspiracy, a Persian nobleman named Megaphernes, a wearer of the royal purple; and along with him another high dignitary among his subordinate commanders.

From this place they endeavoured to force a passage into Cilicia. Now the entrance was by an exceedingly steep cart-road, impracticable for an army in face of a resisting force; and report said that Syennesis was on the summit of the pass guarding the approach. Accordingly they halted a day in the plain; but next day came a messenger informing them that Syenesis had left the pass; doubtless, after perceiving that Menon's army was already in Cilicia on his own side of the mountains; and he had further been informed that ships of war, belonging to the Lacedaemonians and to Cyrus himself, with Tamos on board as admiral, were sailing round from Ionia to Cilicia. Whatever the reason might be, Cyrus made his way up into the hills without let or hindrance, and came in sight of the tents where the Cilicians were on guard. From that point he descended gradually into a large and beautiful plain country, well watered, and thickly covered with trees of all sorts and vines. This plain produces sesame plentifully, as also panic and millet and barley and wheat; and it is shut in on all sides by a steep and lofty wall of mountains from sea to sea. Descending through this plain country, he advanced four stages—twenty-five parasangs—to Tarsus, a large and prosperous city of Cilicia. Here stood the palace of Syennesis, the king of the country; and through the middle of the city flows a river called the Cydnus, two hundred feet broad. They found that the city had been deserted by its inhabitants, who had betaken themselves, with Syennesis, to a strong place on the hills. All had gone, except the tavern-keepers. The sea-board inhabitants of Soli and Issi also remained. Now Epyaxa, Syennesis's queen, had reached Tarsus five days in advance of Cyrus. During their passage over the mountains into the plain, two companies of Menon's army were lost. Some said they had been cut down by the Cilicians, while engaged on some pillaging affair; another account was that they had been left behind, and being unable to overtake the main body, or discover the route, had gone astray and perished. However it was, they numbered one hundred hoplites; and when the rest arrived, being in a fury at the destruction of their fellow soldiers, they vented their spleen by pillaging the city of Tarsus and the palace to boot. Now when Cyrus had marched into the city, he sent for Syennesis to come to him; but the latter replied that he had never yet put himself into the hands of any one who was his superior, nor was he willing to accede to the proposal of Cyrus now; until, in the end, his wife persuaded him, and he accepted pledges of good faith. After this they met, and Syennesis gave Cyrus large sums in aid of his army; while Cyrus presented him with the customary royal gifts—to wit, a horse with a gold bit, a necklace of gold, a gold bracelet, and a gold scimitar, a Persian dress, and lastly, the exemption of his territory from further pillage, with the privilege of taking back the slaves that had been seized, wherever they might chance to come upon them.

1 "Targeteers" armed with a light shield instead of the larger one of the hoplite, or heavy infantry soldier. Iphicrates made great use of this arm at a later date.

4 Lit. "inhabited," many of the cities of Asia being then as now deserted, but the suggestion is clearly at times "thickly inhabited," "populous."

6 Perhaps this should be Agias the Arcadian, as Mr. Macmichael suggests. Sophaenetus has already been named above.

7 The Lycaea, an Arcadian festival in honour of Zeus Αρχαιος, akin to the Roman Lupercalia, which was originally a shepherd festival, the introduction of which the Romans ascribe to the Arcadian Evander.

8 Lit. "plain of the Cayster," like Ceramon-agora, "the market of the Ceramians" above, the name of a town.

9 I.e. ready for action, c.f. "bayonets fixed".