Attacks on the Press E-Book

19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Serie: Bloomberg

- Sprache: Englisch

The latest, definitive assessment of the state of free press around the world Attacks on the Press is a comprehensive, annual account of press conditions worldwide, focusing this year on the new face of censorship perpetrated by governments and non-state actors. Compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the 2017 edition documents new dangers and threats to journalists and to the free and independent media. The risks are a combination of familiar censorship tactics applied in novel ways, and the exertion of pressure through unconventional means or at unprecedented levels. These censorship efforts range from withholding advertising to online trolling, website blocking to physical harassment, imprisonment to the murder of journalists. In the Americas, governments and non-state actors use new, sometimes subtle ways to limit journalists' ability to investigate wrongdoing. In Europe, authorities deploy intelligence services to intimidate the press in the name of national security. In Asia, governments block access to information online, and in some cases, punish those who manage to get around the obstacles. And throughout the world, terror groups are using the threat of targeted murder to compel journalists to refrain from covering crucial stories or otherwise self-censor. Attacks on the Press documents how these new forms of censorship are perpetrated and provides journalists with guidance on how to work around them, when possible, and how to ensure their own safety as well as the safety of their sources and people with whom they work. The book enables readers to: * Examine the state of free media around the world * Learn which nations violate press freedom with impunity * Discover the most dangerous beats and regions * Delve inside specific, increasingly complex challenges CPJ's mission is to defend the rights of journalists to report the news without fear of reprisal. Attacks on the Press provides a platform for direct advocacy with governments and the diplomatic community, for giving voice to journalists globally, and for ensuring that those journalists have a seat in discussions at the United Nations, the Organization of American States, the European Union, the African Union, and others.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 331

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

The Committee to Protect Journalists is an independent, nonprofit organization that promotes press freedom worldwide, defending the right of journalists to report the news without fear of reprisal. CPJ ensures the free flow of news and commentary by taking action wherever journalists are attacked, imprisoned, killed, kidnapped, threatened, censored or harassed.

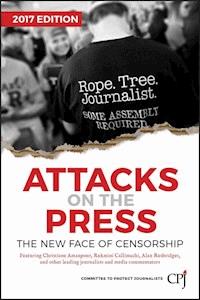

Attacks on the Press

2017 EDITION

The New Face of Censorship

Committee to Protect Journalists

Cover photo: Supporters gather to rally with Donald Trump, then the Republican presidential nominee, in a cargo hangar at Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on November 6, 2016. (REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst)

Editor: Alan Huffman Editorial Director: Elana Beiser Copy Editor: April Simpson

Copyright © 2017 by Committee to Protect Journalists, New York. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

The previous editions of Attacks on the Press were published by Bloomberg Press in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

ISBN 9781119361008 (Paperback)

ISBN 9781119361015 (ePDF)

ISBN 9781119361060 (ePub)

CONTENTS

Introduction: The New Face of Censorship

1. Where I’ve Never Set Foot

2. From Fledgling to Failed

3. A Loyal Press

4. What Is the Worst-Case Scenario?

5. Thwarting Freedom of Information

6. Disrupting the Debate

7. Discredited

8. Chinese Import

9. Willing Accomplice

10. Edited by Drug Lords

11. Self-Restraint vs. Self-Censorship

12. Connecting Cuba

13. Supervised Access

14. Fiscal Blackmail

15. Right Is Might

16. Eluding the Censors

17. Zone of Silence

18. Being a Target

19. Fighting for the Truth

Index

EULA

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Chapter

Pages

1

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

65

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

81

82

83

84

85

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

Introduction: The New Face of Censorship

By Joel Simon

In the days when news was printed on paper, censorship was a crude practice involving government officials with black pens, the seizure of printing presses and raids on newsrooms. The complexity and centralization of broadcasting also made radio and television vulnerable to censorship even when the governments didn’t exercise direct control of the airwaves. After all, frequencies can be withheld; equipment can be confiscated; media owners can be pressured.

New information technologies—the global, interconnected internet; ubiquitous social media platforms; smartphones with cameras—were supposed to make censorship obsolete. Instead, they have just made it more complicated.

Does anyone still believe the utopian mantras that information wants to be free and the internet is impossible to censor or control?

The fact is that while we are awash in information, there are tremendous gaps in our knowledge of the world. The gaps are growing as violent attacks against the media spike, as governments develop new systems of information control and as the technology that allows information to circulate is co-opted and used to stifle free expression.

In 2014, I published a book about the global press freedom struggles, The New Censorship. In this year’s edition of Attacks on the Press, we have asked contributors from around the world—journalists, academics and activists—to provide their perspectives on the issue. The question we have asked them to answer—with apologies to Donald Rumsfeld—is why don’t we know what we don’t know.

Following the polarizing election of Donald Trump in the United States, concerns were raised about the rise of fake news and the hostile and intimidating environment created by Trump’s heated rhetoric. But around the world, the trends are deeper, more enduring and more troubling. These days, the strategies to control and manage information fall into three broad categories that I call repression 2.0, masked political control and technology capture.

Repression 2.0 is an update on the worst old-style tactics, from state censorship to the imprisonment of critics, with new information technologies, including smartphones and social media, producing a softening around the edges. Masked political control means a systematic effort to hide repressive actions by dressing them in the cloak of democratic norms. Governments might justify an internet crackdown by saying it is necessary to suppress hate speech and incitement to violence. They might cast the jailing of dozens of critical journalists as an essential element in the global fight against terror.

Finally, technology capture means using the same technologies that have spawned the global information explosion to stifle dissent by monitoring and surveilling critics, blocking websites and using trolling to shut down critical voices. Most insidious of all is sowing confusion through propaganda and false news.

These strategies have contributed to an upsurge in killings and imprisonment of journalists around the world. In fact, at the end of 2016, there were 259 journalists in jail, the most ever documented by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Meanwhile, violent forces—from Islamic militants to drug cartels—have exploited new information technologies to bypass the media and communicate directly with the public, often using videos of graphic violence to send a message of ruthlessness and terror.

In his essay, CPJ’s deputy executive director, Robert Mahoney, describes the global safety landscape and looks at the ways that journalists and media organizations are responding to these troubling trends. The threat of violence is stifling coverage of critical global hot spots from Syria to Somalia to the U.S.-Mexico border, creating a dangerous information void.

Two essays describe strategies journalists are using to respond. As a reporter for the AP based in Senegal, Rukmini Callimachi worked the phones to cover the no-go zones in neighboring Mali, developing sources and an intimate knowledge of the country that allowed her to provide rich, informed coverage once she was able to get in on the ground. Callimachi replicated these efforts to cover terror networks around the world as a reporter for The New York Times. Similarly, Syria Deeply managing editor Alessandria Masi has covered every aspect of the Syrian conflict without ever setting foot inside the country.

The new technologies that allow criminal and militant groups to bypass the media and speak directly to the public have made the world exceptionally dangerous for journalists reporting from conflict zones. But this same process of disintermediation poses challenges to authoritarian regimes around the world that in the past have often managed information through direct control of mass media. Popular movements—from the Color Revolutions to the Arab Spring—have been fueled by information shared on social media, and because anyone with a smartphone can commit acts of journalism, it’s impossible to jail them all.

Finding the balance between the repressive force necessary to retain control and the openness necessary to benefit from new technologies and participate in the global economy is an ongoing challenge for authoritarian regimes. As Jessica Jerreat notes, in North Korea modest cracks are emerging in the wall of censorship with the opening of an AP bureau and the growing use of cell phones, even if these phones are monitored and controlled. In Cuba, a new generation of bloggers and online journalists criticize the socialist government from a variety of perspectives, and although they face the prospects of harassment and persecution, they are not subject to the mass jailing of journalists in the previous decade.

Outside the world’s more repressive countries, governments generally seek to hide their repression behind a democratic veneer. In his book The Dictator’s Learning Curve, William J. Dobson describes how a generation of autocratic leaders uses the trappings of democracy, including elections, to mask their repression. I have dubbed these elected autocrats democratators.

President Recep Tayyip Erdog an of Turkey is perhaps an exemplar, and while his country jails more journalists than any other, Andrew Finkel shows in his essay how Erdog an’s government also exercises control over the private media using direct pressure, regulatory authority and the law as a blunt instrument to ensure obeisance. Likewise, in Egypt, which has seen a massive upsurge in repression, the government of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has expended considerable energy and effort to build a loyal press.

In Mexico, a country that has experienced a democratic transition, an infamous, near-perfect record of impunity in the murders of journalists, coupled with the manipulation of government advertising and strategic lawsuits, has cast a chill over the country’s media, according to New York Times correspondent Elisabeth Malkin. As Alan Rusbridger notes in his detailed report on the Kenyan media scene, “Murder is messy. Money is tidy.”

These strategies focus on political control and manipulation. But, of course, governments also seek to capture the technology that journalists and others rely on to disseminate critical information. These same technologies can be used for surveillance, blocking, trolling and the dissemination of propaganda. In her essay, Emily Parker contrasts the approaches of China and Russia, noting that Russia failed to grasp early on the political threat posed by the World Wide Web and thus has been playing catch-up. Today, even as Russia struggles to curtail online dissent, it is developing what could be termed offensive capabilities, using the internet to spread propaganda and manipulate public opinion domestically and around the world.

Other governments, including China, are also innovating. One of the most dramatic and disturbing examples is the development of a tracking system based on credit scores. As described by Yaqiu Wang, Chinese journalists who post critical content on social media could receive poor credits scores, resulting in the denial of loans or high interest rates. The government of Ecuador, according to Alexandra Ellerbeck, is alleging copyright and terms of service violations in pressuring Twitter and Facebook to remove links to sensitive documents that expose corruption. Meanwhile, governments, including of the United States, are promoting the concept of transparency by releasing reams of data, which, while welcome, are often of limited utility. And journalists who file freedom of information requests face impediments ranging from delaying tactics to exorbitant fees.

As with any book, and particularly one of this nature, a lot will have changed by the time this edition of Attacks on the Press comes out. Circumstances are extraordinarily volatile around the world, including in the United States, as Christiane Amanpour and Alan Huffman note in their chapters. Overall, the landscape of new censorship is bleak, and the challenges significant. The enemies of free expression have attacked the new global information system at every level, using violence and repression against individual journalists, seeking to control the technologies on which they rely to deliver the news, and sowing confusion and disinformation so that critical information does not reach the public in a meaningful way.

But the fight is far from hopeless. It is important to keep in mind that the upsurge in violence and repression against the media, and the development of new strategies of repression, are responses to the liberating power of independent information. Technology continues to serve the voices of critical dissent, as Karen Coates describes in her essay on Facebook journalism.

Journalists cannot allow themselves to feel demoralized. They need to pursue their calling and to seek the truth with integrity, honestly believing that the setbacks, while real, are temporary. As Amanpour argues in the closing essay in this volume (adapted from a speech she gave at the CPJ awards dinner in November 2016), journalists must “recommit to robust fact-based reporting without fear or favor—on the issues” and not “stand for being labeled crooked or lying or failing.” This is the best and most important way to fight back against the new censorship.

Joel Simonis the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. He has written widely on media issues, contributing to Slate, Columbia Journalism Review, The New York Review of Books, World Policy Journal, Asahi Shimbun and The Times of India. He has led numerous international missions to advance press freedom. His book The New Censorship: Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom was published in November 2014.

1.Where I’ve Never Set Foot

By Alessandria Masi

Syrian children react after what activists said was shelling by forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad near the Syrian Arab Red Crescent center in Damascus on May 6, 2015.

(Reuters/Bassam Khabieh)

The morning after the attack my deputy editor and I lit cigarettes as we squatted on the green couch in our closet-sized Beirut office, hanging out the window and talking about what we thought had really happened in Syria.

Here were the facts: On September 17, 2016, the U.S. and several coalition partners had launched several air strikes on a Syrian military base in the province of Deir Ezzor, in eastern Syria, killing 62 soldiers. Syria, at that point, had been on the sixth day of a cease-fire, brokered the week before by U.S. and Russian officials, but the situation was bad. The following days in Syria were some of the bloodiest since the start of the conflict in 2011.

Our news site, Syria Deeply, had already published a report on the attack—mostly bare-bones facts and whatever official statements had been issued by all concerned. We included the official U.S. statement confirming the strike, saying it was an accident. We reported that the United Nations immediately convened an emergency session in an attempt to salvage the already shaky truce. We even reported that Moscow, enraged, said the attack was proof that the U.S. was coordinating with the so-called Islamic State group (IS, or ISIS; the group’s militants were apparently able to advance in the area just minutes after the air strike). These were statements released to the press, to be used by the press to transmit information to the public. But you would be hard-pressed to find anyone, including the two of us, who believed that all three statements were true.

To me, it seemed an insult to the public’s intelligence for us to report that the U.S. was not able to recognize a military base. I am wary of believing anything President Bashar al-Assad says but had to concede that he wasn’t completely wrong in pointing out that “you don’t commit a mistake for more than one hour.” Yet I’ve also been privy to U.S. strategy long enough to know that direct coordination between Washington and ISIS would be an unnecessary risk when there were plenty of willing middlemen at both parties’ disposal, and it seemed unlikely that the U.S. would willingly obliterate its own cease-fire deal.

A few days later, over wine and Armenian food on my balcony in Beirut, another journalist shared that a prominent NGO (non- governmental organization) spokesperson blamed the attack on Russia, saying Moscow had cleared the target with the Americans before the strike.

None of these possibilities made it into the news brief. It’s not because we too were lazy to confirm our theories, nor because we didn’t have the sources or lacked understanding of Syria. Six years into the conflict that has killed hundreds of thousands of people, flooded other countries with nearly 4.8 million refugees and drawn in foreign powers from all corners of the world, journalists reporting on Syria must censor themselves through omission. This isn’t new—covering Syria has always involved a certain amount of self-censorship, either for security reasons (names are always changed) or for ethical reasons (we omit pictures of the dead). But now, ironically, we do it to try to remain unbiased. We walk on eggshells for the sake of balance and because the majority of us cannot go to Syria to see things for ourselves, which means we are forced to report only what we are told.

As a journalist and managing editor of Syria Deeply, I realized that omitting our theories and reporting only those questionable statements accomplished two things: Readers were informed that the strike happened, and, as a publication, we left very little room for accusations of bias. We reported all sides’ statements.

I have a recurring nightmare about Syria. I wake up one day, when the war is over, to find that all the information we reported as fact—everything we thought was true—was not. It’s an irrational thought. As I write this, the conflict has claimed the lives of some 400,000 people, families have been torn apart, cities have been destroyed, multitudes have fled (and often perished), overwhelming other countries, and millions of Syrians don’t know where they will get their next meal. Those are undeniable facts. The war is taking a huge toll. But I haven’t seen it myself, and there are few people I trust to be my eyes on the ground, because after six years of fighting, the agenda-less are a minuscule percentage of the Syrian population. Government statements are often blatantly misleading, and fear of retribution from government or non-state actors leads civilians and activists to bend or sometimes obliterate the truth. For those of us covering the conflict from the outside, it is hard to know what’s really happening, so we either self-censor or grudgingly provide a platform for people whose accounts may be wildly divergent or entirely untrue.

When Russia first began its air campaign in Syria in October 2015, I was in Beirut. As the first reports of the strike came out, I called a Syrian source in the town that was hit, who provided me with recordings of intercepted radio communications in Russian coming from the warplanes. Moscow had already put out their statement claiming to have joined the war in Syria under the pretense of fighting ISIS. But looking at my map of Syria, I found the first town that had been hit circled in red—it had been under siege for more than a year and was under the control of a Syrian rebel group, not ISIS.

My editors in New York were skeptical. “Why would Russia bomb the rebels when they have explicitly said they are bombing ISIS?” they asked. “It doesn’t make sense.” The majority of news outlets had already published the Russian government statement about their fight against ISIS, and I was contradicting this. My sources were part of the opposition and because of their affiliation I had to be cautious; they had every reason to lie.

In the days that followed, it became common knowledge that regardless of Moscow’s official statement, Russia was in Syria to defend Assad, and this meant targeting any group that opposed him, including the rebels. Yet we continued to include the official Moscow statement in our reporting.

Politicians have always lied, and it has always been the responsibility of journalists to filter these statements or juxtapose them with evidence proving them false. But in Syria, even evidence is presented subjectively, and obtaining your own eyewitness account can mean jail or a death sentence.

So we choose to err on the safe side, which often sounds like this:

Russian air strikes hit a hospital in Aleppo, though Moscow claims it is fighting ISIS in Syria.

Air strikes hit a school in Syria. It is unclear who carried out the attack—Syria, Russia and the U.S.-led coalition (the only players with air power in the country) all denied involvement.

Patrick Cockburn wrote in his book The Age of Jihad, “Media reporting has been full of certainties that melt away in the face of reality. In Syria, more than most places, only eyewitness information is worth much.” It is this that worries me the most. I have seen thousands of photos, videos and reports. I have spoken to dozens of people inside. I have Skyped with activists, detainees and victims. I have gone to conferences. I have met with advocacy groups and tracked the work of humanitarian aid organizations. I have been a secondhand witness to the war and reported closely on it, yet I have never set foot in Syria. Admitting this has given me much anxiety over being labeled a fraud, but it’s the truth, as it is for many international journalists covering the war.

In the early years of the war, when foreign journalists were going into Syria frequently, some with government visas and others crossing the border illegally, I was still in university. When it was finally my turn to cover the war in 2014, journalists were being targeted. The Committee to Protect Journalists estimates that more than 100 journalists have been killed since the start of the conflict. As a direct consequence, coverage has become constricted, most often limited to secondhand accounts.

Today, there are dozens of Syrian journalists still inside the country risking their lives to report the news. (CPJ investigated the deaths of at least 90 in 2015 but was only able to confirm that 14 were killed that year because of their work.) However, most are confined to either opposition-held or government-held areas and cannot cross front lines for their work. Some are able to publish their own work on local and international media outlets, but the majority transmit information through their social media accounts, which foreign journalists pick up.

Most foreign journalists reporting on Syria today are doing so from outside the country’s borders. Entering the country illegally is far too dangerous, and even those who take the risk run into difficulties finding news outlets to publish their work; many news outlets prohibit accepting freelancers’ reports due to the personal risk. Visas to report in government-controlled areas are not impossible to obtain, but after being hacked by the Syrian Electronic Army for my reporting and writing extensively on ISIS, my chances of getting one are slim.

Some foreign journalists still go into Syria, and despite the risks, I tried to go myself at the end of 2015 when Syrian activists started a media campaign to draw attention to the thousands of people living under siege in Madaya, outside Damascus. Civilians have been trapped and starving in Madaya since July 2015, but as a result of the media campaign, by year’s end, the city was being covered in the media with unprecedented intensity. Pictures and reports from Syrian journalists and activists of emaciated, undernourished and starved children flooded Twitter and Facebook pages.

The people in Madaya are apparently surrounded and being besieged by Hezbollah, the armed Lebanese group fighting alongside the Syrian regime. Yet when I began trying to get into the city, Hezbollah was telling an entirely different story than was elsewhere reported: There was no siege; people weren’t starving; there was food. So unwavering was Hezbollah about this that some of its fighters offered to take me to the outskirts of the town so I could see for myself the available cornucopia of supplies.

I can’t go into all the details of why that trip never happened (ironically, I must self-censor), but after several calls and one home visit in Beirut from the FBI, I decided the risk would be too high. Months later, Hezbollah and Syrian regime supporters in Beirut continue to echo their claims, while pictures of emaciated civilians continue to circulate and at least 86 people are known to have died of starvation.

Madaya is a microcosm of the Syrian conflict and raises questions I have pondered since I began covering the war: How could two groups so firmly expound drastically different truths about the situation? And who is right?

A cornerstone of the Syrian regime’s public relations campaign since the beginning of the conflict has been to dismiss photographs of violence or the brutal effects of war as opposition or “terrorist” propaganda. Even as I write this, Assad has just told the Associated Press that “if there’s really a siege around the city of Aleppo, people would have been dead by now.” But the humanitarian workers and activists on the ground send evidence of the siege nearly every day. Assad has an answer for that, too: “If you want to talk about some who allegedly are claiming this, we tell them how could you still be alive? . . . The reality is telling.”

Yet the portrayal of reality in Syria is almost always biased. At the start of the war, the majority of people inside Syria were forced to choose a side. Soon after, foreign governments followed suit, voicing support for one cause or another. For the most part, foreign media are still trying to resist this demand to declare allegiance in Syria. But with every story we tell, we risk being labeled either pro-opposition or pro-government: If we publish that Assad is starving his people, we are pro-opposition; if we include that Assad denies these claims, we are enabling a criminal regime. It is meanwhile extremely difficult for us to report undeniable truths from the field.

In response, we have begun to adapt to being sequestered, finding ways to more accurately report on Syria even if we aren’t there. During the siege of Aleppo (still ongoing at the time of this writing), dozens of Syrian journalists and activists communicated real-time updates through a massive WhatsApp group, answering foreign journalists’ questions and sharing photos and videos. For the most part, though, our coverage is necessarily watered down. It is carefully couched and neutralized just in case it isn’t true. It is difficult to call a spade a spade when you haven’t seen it yourself.

There are days when we throw up our hands in frustration and feign surrender, lamenting that “everyone is lying to me about Syria!” Still, we can’t give up. Everyone may be lying, but the war is real. We may not get visas, and even if we do, our risk assessments for trips to Syria may not be approved. Our attempts to uncover the truth may continue to be met with threats and accusations of bias. As long as there are people in Syria who want to tell their stories, we will try to find a way to make them heard. But for the majority of us, being denied the ability to observe circumstances firsthand means that our necessary circumspection and caution, and our desire to remain unbiased, become a form of censorship, too.

Alessandria Masiis managing editor of Syria Deeply and Beirut bureau chief of News Deeply.

2.From Fledgling to Failed

By Jacey Fortin

South Sudanese government soldiers stand in trenches in Malakal in October 2016. The army flew in journalists to show that they retain control of the city, which has been reduced to rubble and almost entirely deserted by civilians.

(AP/Justin Lynch)

Juba, South Sudan—The shooting began around 5:15 on a Friday afternoon.

Dozens of journalists had gathered in the pressroom at the Presidential Palace—a walled compound also known as “J1”—in the capital city. Following a few days of rising tensions, culminating in a checkpoint shoot-out just the night before, the president, Salva Kiir, and the vice president, Riek Machar, former wartime rivals, were expected to hold a news conference calling for peace.

The journalists had been waiting for a couple of hours when they heard gunfire outside. Most of them dropped to the floor. A woman working security by the door fumbled with a gun she didn’t seem to know how to operate, making everyone nervous.

After about an hour, the shooting subsided and Kiir and Machar finally appeared, first to urge calm following the gunfire, about which they professed to know little, then to give prepared speeches about the state of the nation.

It was the day before the fifth anniversary of South Sudan’s independence.

The journalists waited for hours until it was deemed safe to leave J1. Around midnight, they piled into the beds of pickup trucks and were escorted by soldiers back to a hotel. None were hurt. Some had spotted bloodied corpses on the pavement as they made their way out of the gates.

“The incident at J1,” as it has become known in government parlance, marked a new era for South Sudan. The world’s youngest country has had a succession of such eras, beginning in 2005, when decades of war against the armed forces of Sudan ended and a fledgling southern government was supposed to be laying the framework for a new state.

Then came 2011, when a landslide referendum created an independent nation. High-ranking officials in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, or SPLA, set themselves to the task of building a nation—a daunting task for a group of war veterans who had made a career of armed struggle.

December 2013 saw the beginning of a civil war that would kill tens of thousands and displace millions, pitting those loyal to President Kiir, a member of the Dinka ethnic group, against those loyal to former Vice President Machar, a member of the Nuer ethnic group. Amid the upheaval, censorship efforts only worsened, with the government often equating criticism with opposition sympathies.

In April 2016, in accordance with a peace deal, Machar moved back to Juba to resume his post as Kiir’s deputy so that the two could preside over the formation of a new transitional government.

That arrangement grew increasingly tense. After clashes erupted at J1 in July, they spread across the city, killing hundreds. Machar and his troops were forced out of town. He remains in exile, while skirmishes outside the capital continue, reminiscent of the civil war that was supposed to have ended.

■ ■ ■

With each passing era, the state of press freedom and media censorship has only gotten worse. Even during peacetime, there was a concerted effort to thwart the establishment of a free press in the nascent country: Journalists faced arrests, outlets suffered shutdowns, and media protection laws were ignored. But war has only made things worse, creating an atmosphere of increased militancy and fear. Journalists know that an article deemed to be criticizing the president or his cronies could cost them their freedom or even their lives. Government workers have been known to appear at printing presses to excise newspaper articles deemed offensive. Even the U.N. has made it difficult for journalists to access key information.

Things have never been easy, observed Emmanuel Tombe, deputy director of Bakhita Radio, a community station in Juba. Like so many other local media organizations, Bakhita’s first challenge has been simply to stay afloat in a dismal economy. It is a daily struggle even to cover the basics such as staff salaries, studio equipment and generator fuel.

Bakhita is first and foremost a Catholic station, with an emphasis on family-friendly sermons and religious hymns. But it also had three English-language shows dedicated to current events, so it has not been immune to government intimidation, threatened shutdowns and even attacks on staffers in the years since its founding in 2006.

“With the conflict right now, the media is even more threatened,” Tombe said in August 2016. Not only did insecurity make it harder to get community funding, it also caused the station to tone down its political reporting, including shutting down “Wake Up Juba,” a morning show that sought to engage government leaders in discussions about local problems. The show touched on everything from low-level corruption to political upheavals. In another concession, the station stopped taking outside callers to ensure that no one stirred up controversy on-air.

“The station could be shut down or taken to court; anything could happen,” Tombe said. “We also have to worry about the presenter of the program. If the presenter is at risk, his safety can be ensured when he’s within the office. But when he’s home, what will happen? Nobody knows.” For now, lying low strikes Tombe as the best way to protect his staffers and to keep the cash-strapped station afloat.

By mid-July 2016, it had become clear that the government, having pushed Machar’s troops out of the city, seemed all the more eager to clamp down on free speech, especially after its soldiers committed a fresh wave of brutal human rights abuses against civilians. That has forced some journalists to self-censor, for fear of provoking a government whose military has never shown respect for media freedoms. Other journalists, both local and foreign, have chosen to leave the country altogether.

One of the most experienced foreign correspondents in South Sudan, freelancer Jason Patinkin, left the country in August 2016. He had just filed a story for The Associated Press documenting a gruesome rape epidemic, mostly committed by SPLA soldiers against Nuer women. “Given the sensitivity of the story I wrote, which was heavily attacked by these pro-government trolls online, whom many believe are on the payroll of the government, I didn’t feel safe,” he said. “So I left, and I still don’t necessarily feel safe going back.”

But escape is not an option for everyone. “Of course South Sudanese journalists face far, far greater risks and greater restrictions than foreign journalists,” Patinkin said. “The things they put up with for their belief in the truth about South Sudan has my deepest honor.”

■ ■ ■

“This is my country. I know people who fought and died for this country,” said Hakim George Hakim, a South Sudanese video correspondent for Reuters. “And I believe that the only difference between a journalist and a soldier is that we are fighting with our pen and our opinion, while the soldier has a firearm.”

Hakim says that both the government and the opposition are deserving of criticism. But his opinions have gotten him into trouble many times. From what he can tell, the blowback comes not in response to his professional work, but to the views he expresses on his personal Facebook page, which are mostly general posts about how journalists should not be targeted and how the government and the opposition are both failing the people. His professional work—mostly videography for a newswire—cannot serve as a platform for his opinions, but he is dedicated to vocalizing his thoughts on social media to push for peace in South Sudan.

In 2016, someone broke into Hakim’s parked car and took only an envelope of personal documents. He has been trailed by government vehicles more than once. He has been warned that his name had been placed on a no-fly list at Juba International Airport. He has received dozens of anonymous phone calls asking him to take down certain Facebook posts.

Some of those calls threatened violence. “Somebody would call me and say, ‘Do you want your family to cry soon? About losing you?’” he said.

Not all media workers who lost their lives in 2016 were targeted for their work. Kamula Duro, a cameraman working for President Kiir himself, died of gunshot wounds during the clashes in July, with no suggestion that he was intentionally targeted.

Shortly thereafter, a journalist working for the international organization Internews was gunned down while sheltering in a hotel compound on the outskirts of Juba. John Gatluak had been working for Internews for four years and was by all accounts a thoughtful, professional and notably dedicated journalist. The scarification on his forehead identified him clearly as a member of the Nuer ethnic group, and Internews believes it was this alone—not Gatluak’s work—that singled him out for a summary execution on July 11, 2016.

Still, there is no question that journalists’ work has put them at risk. At a press conference in August 2015, President Kiir made a statement that has lived in infamy ever since. “The freedom of press does not mean that you work against your country,” he said. “And if anybody among them does not know that this country has killed people, we will demonstrate it one day on them.”

Four days later, the newspaper journalist Peter Moi was shot dead by unknown assailants as he walked home from work. And in December 2015, newspaper editor Joseph Afandi was arrested and detained for nearly two months, possibly in connection with an article criticizing the SPLA. In March 2016, just weeks after his release, Afandi was abducted, severely beaten and dumped near a cemetery in the capital.