7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

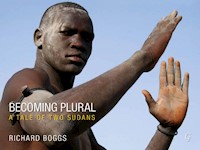

In July 2011, Sudan officially 'became plural', as the country split in two; the unofficial north - south divide between the Arabdominated north and the more ethnically African south was formalised, after the people of Southern Sudan voted overwhelmingly to separate from the rest of the country. Becoming Plural is a beautifully illustrated travelogue containing over 100 unique photographs of Sudanese people and their lives, accompanied by a first-hand narrative of what life in Sudan was really like during this critical time in its history. Richard Boggs lived and worked among the Sudanese people for many years, first coming to Sudan as a volunteer in 1986. He has lived in both Juba and Khartoum, and shared the reality of life in Sudan with the people around him. This has enabled him to provide an intimate portrait of the characteristics and values of the Sudanese people. He conveys astutely the particular circumstances in which they live, creating a record of their hopes and fears as Sudan formally breaks into two separate states. This book will have enormous appeal to those who appreciate travel writing, photography and ethnography, as well as those interested in the historic circumstances of the split between North and South Sudan.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

BECOMING PLURAL

A TALE OF TWO SUDANS

RICHARD BOGGS

BECOMING PLURAL

A Tale of Two Sudans

Published by

Garnet Publishing Limited, 8 Southern Court, South Street, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 4QS, UK

www.garnetpublishing.co.uk

www.twitter.com/Garnetpub

www.facebook.com/Garnetpub

blog.garnetpublishing.co.uk

Copyright © Richard Boggs, 2013

Image copyright © Richard Boggs, 2013 (unless otherwise stated)

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. First Edition

ISBN: 9781859642979

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design bySheer Design and Typesetting: www.sheerdesignandtypesetting.com

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE: ENCOUNTERS

CHAPTER TWO: INTO THE MYSTIC

CHAPTER THREE: THE MEN OF THE NINETY-NINE MOUNTAINS

CHAPTER FOUR: NEW SUDAN?

CHAPTER FIVE: BENEATH THE HOLY MOUNTAINS

CHAPTER SIX: THE CORAL CITY OF SUAKIN

CHAPTER SEVEN: IN THE LAND OF KUSH

CHAPTER EIGHT: BRAVE NEW WORLD

CHAPTER NINE: POSTCARD FROM DARFUR

CHAPTER TEN: SUDANS?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GLOSSARY

To Ismael on the island

Sudan before July 2011

Ferry to the island, Kerma Mahas, Nubia

In the history of independent Sudan there has always been a persistent and pervasive assumption that Sudan was an Arab nation all of whose citizens would eventually adopt Arab culture, language and religion.1

1.Collins, Robert,A History of Modern Sudan(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p.137

CHAPTER ONE

ENCOUNTERS

SALVATION

ISTEP DOWN INTOthe pool of the Grand Hotel on Nile Avenue and break the dusty film of its surface. Mahogany trees, trees General Horatio Kitchener is said to have planted when he rebuilt Khartoum, grace the Blue Nile beyond. Kites drift languidly on the air currents overhead: this is a city of kites and sparrows.

Already I’m breaking the law: there are two of us in the pool – with winter temperatures of 25 degrees it’s too cold for the Sudanese – and the other swimmer is a woman. To ensure no hanky-panky in Khartoum waters, swimming times alternate with the hour, by law. In theory, even a husband and wife must swim at different times, although the staff turn a blind eye to all that.

For entertainment it’s Abba this year, sounding out over the vast expanse of the empty pool, calling out for a man after midnight. Last year it was Celine Dion. A new year brings a new album.

Back in the colonial heyday in the 1930s, the artist Richard Wyndham found the Grand Hotel almost intimidating, as if he had entered ‘the sacred portals of a club’. All was silence as the waiters walked barefoot among the guests, except for the chink of ice in gin and the rotation of the ceiling fans. The Grand Hotel was very, very grand. Nowhere, Wyndham concluded, could ‘the white man’s burden be more nobly borne’.1

From Khartoum, Wyndham travelled by train to Kosti, rather comfortable in his sleeper, and after enjoying his breakfast of kippers, declared the journey with Sudan Railways ‘a luxury unknown in Europe’.2When his boatarrived in Malakal, the porters rushed up to the cabins, naked apart from a rope tied decoratively around the waist. Even the globe-trotting American lady on board gasped with surprise, if not admiration. Today, notices in the hotel changing rooms warn bathers of the need to ‘respect Sudanese traditions’ (Whose traditions are those? I ask myself) and warn gym-users against any nudity while changing.

Things were also a little different when Frank Power, a correspondent forTheTimesof London, travelled to Khartoum to join the forces that were to fight the Mahdi rebelling against Turco-Egyptian rule. He wrote home in 1883 about the dress code of the day: ‘After Berber, the natives (ebony giants) wear a knife strapped to the elbow as their sole clothing; the women natives, a five-inch fringe of blue and white china beads strung on thread.’3

Things have somewhat changed from the latter days of my youth when I was a volunteer in Sudan, and would take the ferry across to Tuti Island, then to Bahari to join the other bathers skinny-dipping in the Nile. When I first came to Sudan in 1986 there had been a sense of a country in crisis: basics were scarce in Khartoum and there were volatile demonstrations against shortages and the cost of living. But while others were waiting to buy bread, I’d be wanting to photograph the baker, all aglow in the warm light, setting out the circles of dough on the wooden plank that he would shove into the oven, withdrawing a minute later the thin flat circles of bread that are eaten with every meal.

The rule of Gaafar Numeiri had finally come to an end in 1985; a popular uprising forced his generals to remove him and pass power to a democratically elected government with Sadiq al-Mahdi as Prime Minister. But things were falling apart: Sudan was on the brink, but we were not sure as to the brink of what.

As volunteers, we were fairly immersed in the culture, living like everyone else on the staplefuulbeans – breakfast wasfuulwith salad, supper wasfuulwith cheese – but we were able to indulge ourselves on occasion. One June evening we treated ourselves to a night out in General Gordon’s with a bottle of gin in a bucket of ice set on the table. Replete and in fine form, we hitched a lift in the back of a pickup from Khartoumproper to Omdurman, and as we crossed the bridge over the White Nile, a colleague noticed that there were not the usual soldiers posted at such a strategic site.

Pot offuul

‘There are no sentries on the bridge,’ he quipped. ‘There’ll be a coup tonight!’ There was. That was my last public consumption of Ethiopian gin in Khartoum. The coup marked the coming of ‘Salvation’, for that’s what the military regime came to call itself: Salvation.

THE VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE

As you travel over Omdurman Bridge you get one of the best views in Khartoum: the Blue Nile flowing from Lake Tana in Ethiopia, its waters divided by the green of Tuti Island, and the White Nile, seemingly more sluggish above the bridge, a vast expanse of water stretching to the horizon. The waters of the Blue Nile have lost some of their sediment on their journey but seem to flow with speed; the White Nile looks a more leisurely silty-grey. At the confluence, they don’t immediately merge and the Nile retains a two-tone effect downstream. A traveller in the early 1900s wrote of the tendency of the waters to remain separate even after the Niles join:

[T]he waters of the two rivers never seem to blend ... the effect is that of dark, turbulent water rushing past a still lake of muddy white, and there is a distinct line when the waters actually meet. It is not until it gets some miles north of Omdurman that the water takes the colour which it bears on reaching Egypt – the colour of the White and Blue Niles blended.4

The British brought the iron bridge over from India I was told. You can stand there and watch the waters flow in a flurry of eddies, and see the ‘Parliament’ building and the Two Niles Mosque. Beneath the bridge there is an island – not Tuti Island, but a little island that is seasonally submerged then cultivated when the waters subside.

One day, I climbed down one of the ladders on the pillars of the bridge to the pumpkin fields of the island, fields the size of a room in a terraced house, walled with earth to catch the water pumped up from the Nile and tended by the hired labourers from the west who live in their strawrokubason the Nile banks. This for me is the sound of the Nile: the ‘putt, putt, putt’of the pumps rhythmically pouring their water into the irrigation ditches that define the fields, fields that mirror the sky in the late afternoon as they are transformed into clay-walled pools.

On the island you might catch a boat being loaded with baskets of aubergines, or hear a shepherd singing. In winter, farmers plough the rich earth that the Nile has yielded. With the rains, the island is flooded again and pelicans fish where oxen once ploughed. On winter days, the riverbanks are isolated, except maybe for a fisherman sitting by his net or the ashen-grey flap of a heron. On warmer days, men from the shanty towns come down to wash themselves and their clothes. Here and there, someone will be crouched on an isolated rock, scrubbing himself down with a piece of net and some soap, scouring the pale soles of the feet with a stone, or standing on the shore, holding the loosesirwaltrousers up above the head for a couple of minutes to dry in the breeze, his skin the rich black of the pendant aubergines that ripen in the fields by the Two Niles Mosque.

ARABIC LESSONS

When I first lived in Khartoum, teaching English at the Islamic University, I lived right in the heart of Omdurman. In thesuq,women served tea in the alleys and men from the Gezira hawked coffee on great circular trays, going from merchant to merchant, the coffee kept hot by embers turning to ash among thejabinas.

The coffee-sellers would be up before the sun had risen over the brown landscape of Omdurman: the brown mud of the indigenousjaloushouses, the house-walls coated with sun-dried dung and straw that kept the homes cooler in summer, the sky itself opaque when a dust-storm threatened. In some half-built concrete block they would be setting up the metal pots on the tray for the first customers of the day, the coffee spiced with ginger, the littlefinjanor handle-less cup heaped with sugar. In those days, I didn’t boil a kettle in a kitchen: the day began with a coffee shared with the labourers of the street.

My Arabic lessons were around the women who sell tea under the neem trees. The tea women of Sudan sit like queens in state, often fat and draped in theirtobes, their throne a stool six inches off the ground.

Tea under the tree, Khartoum

Around the tea women are the tools of their trade: the charcoal stove of woven metal, the milk tins recycled as kettles to boil water, the tray of glasses heaped with sugar. They sit with authority as the men squat around, waiting for their tea or demanding another spoonful of sugar. Then the men argue over who should pay, each insisting that he should pay for the others, one pushing the other back as he reaches for the notes in his shirt pocket, ‘I’ve sworn! I’ve sworn!’ he calls, until his friend yields, and that’s the excitement over for the day.

Before they knocked it down, the old corrugated-iron-roofed fruit and vegetable market in Khartoum was where I tried out my Arabic. There I’d drink coffee with the men who had gathered at the kind of hiring fair that took place under the scented neem trees, hoping for a day’s work. It was there that I gave myself up to the rhythms of colloquial Arabic, absorbing the language of thesuq,not the university where I worked.

Around me, the traders would be seated high up above the fruit and vegetables in the market stalls, urging passers-by to purchase dates that were ‘pure sugar’ or oranges that were ‘sweet as honey’. Or they would stand in their shops behind the various tins stacked withfuulbeans or garlic, the beans a dusty pyramid in the glare of the sun.

Women would throw up their arms in feigned disbelief at the price being asked, then walk away, only to be called back with a more reasonable offer. And still she’d refuse, until the stall keeper would swear that she was offering less than he had himself paid. And as each harangued the other, you’d hear exclamations of ‘W’Allah sa! W’Allah sa!’ ‘By God, it’s true! It’s true, by God!’ It might even have ended with the stall keeper swearing that if he were not speaking God’s truth he would divorce his wife.

OmdurmanSuq

I’d sit with the casual labourers of thesuq, gathered around thesheeshapipe, the pipe passing from mouth to mouth. As the talk flowed and the bubbles streamed in the pipe, I’d be surrounded by the sounds of the market: boys selling single cigarettes, men throwing down watermelons from a lorry to be piled in a heap in the sun, fruit sellers urging passers-by to buy grapefruit and bananas and dates.

In thesuq, Umm Ruwaba

And so, apart from the interruption of morning classes, I idled away the hours from the first greetings of the morning to the last leisurely chat in the cool of the evening. My school was thesuq: I learnt my Arabic among baskets of lemons from Tuti Island and tomatoes from the Gezira laid out on empty cement bags on the street, and baskets of aubergines from the banks of the Nile.

THE DETAILS

A faint acrid whiff sometimes hangs over the city. The brick-makers on Tuti Island fire their sun-dried bricks of Nile mud, insulated with a layer of smoking cow dung, in kilns on the riverbanks. This, for me, is the distinctive smell of Khartoum.

Brick kilns by the Blue Nile, Rosseires

The mark on the brow of the men, darker than the surrounding grain of the skin, is caused by the forehead touching the ground in prayer. They tend to pray outside on the pavement, the long prayer mat spread below the neem trees. Their faint perfume hinting of hyacinth is the other smell I associate with Khartoum. The shoes, those leopard-skin slippers that the merchants like to wear, environmental awareness being a little thin on the ground, are discarded in a line, the latecomers hurrying to join one of the bowing rows.

Prayers at the scene of themulid, Omdurman

The hennaed patterns on the women’s ankles and on the backs of their hands, like delicately-leafed stems and swirling flowers, have a dusky intricacy. And the way the women hold themselves: they walk with grace but not with speed.

The traditional garment for men is the loose white robe that covers the entire body below the neck, thejelabiyah.Some have a pocket not just on the chest buton the back as well – there’s no back-to-front in the traditional attire of the followers of the Mahdi. The traditional garment for women is thetobe, a loose robe in the colours of exotic birds: lemon, pink, crimson. Traditionally, thetobewas lightly thrown over the top of the head, leaving the hair partly revealed, à la Bhutto. Nowadays, there is the imported style, perceived as more ‘Islamic’, where the face is tightly framed with a dull wrapper.

The faces of the oldest men and women are sometimes ploughed with the scars that used to be cut into the cheek but are now rare. In the past, scarification would have been seen as beautification; the Victorian explorer Samuel Baker, travelling through Sudan in search of big game and the tributaries of the Nile, contrasted perceptions of beauty between here and the west: ‘Scars upon the face are, in Europe, a blemish; but here and in the Arab countries no beauty can be perfect until the cheeks or temples have been gashed.’5Scars are the obvious marks of tribal identity: cuts like the number 111 or a ‘T’ carved into the cheek according to the ethnic group, but today this is more a characteristic of grandmothers at a wedding than Sudanese youth. There is still a wealth of scarification among the Southern tribes however: deep cuts across the brow; a ring of beaded flesh along the forehead; thousands of dots swirling over the entire body.

Western dress, unfortunately, is more popular than before, except for Fridays when it’s traditional white for the mosque. The men’s shirts fall over their polyester trousers, never, apart from those in uniform, tucked in beneath. In Khartoum, you cover your ass.

The taxis are yellow, the shutters and doors of the shops are green, and the city is a dusty brown. Khartoum: drab city by the blue of the Nile in the intense light of the desert sun. But some of the streets are picturesque, with the tea drinkers gathered by thezeers, the clay pots of cool water shaded by the branches of the waxy banyan tree that frame the scene. Taxi drivers idle by their cars, both cars and drivers often looking over half a century old. The drivers tend not to go looking for a fare; they wait for the fare to come to them. Some stretch out indolently on cardboard on the pavement in the midday heat; people here tend towards the horizontal.

Taxi driver, Khartoum

When the men greet each other, one arm extends to tap the other person on the right shoulder, and then there is the embrace or the slapping of the other’s shoulder, and a warm handshake. In Sudan they have their own Arabic.

‘Inta tamam? Mea mea? Shadeed?’ ‘Are you fine? One hundred per cent? Are you strong?’ And the one greeted, as they continue slapping each other on the back, is bound to reply:

‘Mea mea, al hamdilallah!’ ‘I’m one hundred per cent, thank God,’ even if he felt anything but.

When the British explorer Wilfred Thesiger arrived in Khartoum in 1935 it was the expat life that appalled him:

Khartoum seemed like the suburbs of North Oxford dumped down in the middle of the Sudan. I hated the calling and the cards, I resented the trim villas, the tarmac roads, the meticulously aligned streets in Omdurman, the signposts and the public conveniences.6

He went off to Darfur instead, hoping again for Ethiopia’s ‘colour and savagery, hardship and adventure’.7But suburban North Oxford? Obviously Khartoum has somewhat changed since Thesiger’s day.

GENERAL GORDON AND ALL THAT

Khartoum came about because of an incident at a feast. When the Turks were attempting to establish their control over Sudan from Cairo, the local chief, Mak Nimer, butchered the lot while they were feasting in Shendi rather than submit to their rule.

It was this incident that marked the birth of Khartoum. The ruling Pasha, Mohammed Ali, having revenged his son’s death with a general slaughter of the Sudanese, established Khartoum at the confluence of the Niles. From here he would try to control Sudan, the main source of slaves for their armies.

The history of Sudan is very much bound up with its northern neighbour and with the military conquest of Egypt. The British influenced Sudan through Cairo, but with the general insurgency against Turco-Egyptian rule led by the Mahdi, the Awaited One, they wanted to abandon Khartoum, for their interest was Egypt, not Sudan. The issue was not unlike the one facing western powers today: how to withdraw from an occupied country without losing face. General Charles Gordon was sent to do just that: to evacuate Khartoum. However, rather than playing the game and withdrawing, he refused to abandon the population of the garrison town.

The correspondence Power smuggled home to his family in Dublin show how at least one of the besieged empathized with the enemy forces surrounding the city. ‘I am not ashamed to say I feel the greatest sympathy for them, and every race that fights against the rule of Pachas, backsheesh, bribery, robbery, and corruption.’8Power may have been a ‘monocled and sardonic observer of war’,9but he saw the Mahdi’s cause as an honourable one.

Power did not have a lot of faith in the garrison forces defending Gordon’s Khartoum, writing that they had 9,000 incompetent infantry who could be routed by fifty good men and 1,000 cavalry who had never learnt to ride.10He was eventually evacuated from Khartoum, but the steamer went aground before it reached Dongola, and Power was killed when he accepted a local sheikh’s ‘hospitality’.

Power’s perspective, with a westerner identifying with the indigenous, is the exception rather than the rule, although the British Prime Minister William Gladstone also sympathized with the rebelling Sudanese. More typical among western writers is the portrayal of the Mahdi as the Oriental despot, rather than the leader of a people fighting for their freedom.

Winston Churchill is different. Rather than falling for the discourse of Orientalism and portraying the Sudanese as either voluptuous sensualists or religious fanatics, Churchill sees the Sudanese rebellion as primarily a social revolt, with the Mahdi bringing together a people rebelling against the injustices of Turko-Egyptian rule.

They were also rebelling against the justices of that rule as Britain forced Egypt to act against the slave trade. In tackling slavery in Sudan, Gordon had helped bring about the movement under the Mahdi that would drive out the forces of occupation and allow slavery to be restored. Attempting to stop slavery in Sudan was to undermine, as in the American Civil War, society itself.

Not all Europeans in Sudan had qualms about slavery: the Bakers enjoyed a life-long relationship which began when the explorer spotted Florence in an Ottoman slave market in a Bulgarian town and bought her. More disconcerting was the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt who, travelling in Sudan in 1814, documented the horrors of slave-trading in Sudan, with each caravan from Kordofan filling the market in Shendi with slaves. On the domestic scene, however, he concluded that ‘slavery, in the East, has little dreadful in it but the name.’11He bought a slave, a boy of 14, in Shendi ‘for the sake of having a useful and constant companion’ but also as an ostensible reason for travelling to the Red Sea, where he could sell the boy for a profit.12Burckhardt took turns with his slave to ride the camel he had also bought, an arrangement that must have raised a few eyebrows among his fellow travellers. Arriving in Suakin with his clothes in rags, he sold the camel at a considerable loss; concerning his travel companion I found him silent.

It was difficult for the British to keep their hands clean as they dealt with Sudanese and Egyptian rulers. Not unlike the delicate question today of Afghan rulers and opium, Britain had to reconcile governing with dealing with rulers whose main interest was obtaining slaves. Gordon was pragmatic: despite his drive against slavery, after one of his mystical moments he decided the man to save Khartoum from the Mahdi was the greatest Sudanese slave-trader of the day, Zubehr Pasha. This option was unacceptable to the British government; Gordon didn’t get Zubehr and Khartoum was lost.

The protagonists in the Khartoum drama are, of course, the Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdallah, a boat-maker’s son from Dongola, and General Gordon, from Woolwich, son of a Major-General. In this apparent ‘clash of civilisations’ on the Nile, the main protagonists are actually rather similar, both leaders being military mystics, with the Sudanese leader perhaps more orthodox in his beliefs than the Englishman.

Gordon refused to surrender for 317 days,13only to be ‘martyred’ on the palace steps when the Mahdi’s forces took Khartoum, if paintings dramatizing the event are to be believed. It was one of those rare occasions when the British, as opposed to the Sudanese, did not turn up on time. Having outsourced the transportation of the troops as far as Wadi Halfa to Thomas Cook, and then negotiated 120 miles of broken water at the rate of one mile a day (they had 1,500,000 tins of bully beef to load and unload daily)14the rescue mission arrived two days too late. Today, Gordon on the Nile seems not so much a tragedy as the material for an entertaining musical.

With the death of Gordon, the Mahdi briefly ruled Sudan from Omdurman until he succumbed to typhus. In his wish to overthrow corrupt governments who served imperial powers, we can see parallels in today’s Middle East. His Islamic state would have gone far beyond the borders of Sudan; he threatened Empire itself. Was the Mahdi a role model for a Saudi who lived here as a guest of the nation in the 1990s? (As his dangerous liaison with the Sudanese authorities came to an end, Bin Laden left Sudan in 1996 for Peshawar and Afghanistan without getting paid for his construction jobs.)15Any Sudanese I have spoken to have utterly rejected the comparison, protesting, I think, a little too much.

It’s tempting to imagine Bin Laden contemplating his future at the tomb of the Mahdi, but devotions at a tomb would have gone against the tenets of Salafism, although tombs are very much a feature of the landscape and centres of religious devotion for the Sudanese. More important, the mysticism that the Mahdi embraced would have been anathema to Bin Laden’s dour sect. But in their charismatic personalities, their denunciation of corrupt, superficially Islamic governments and their fusion of religion and politics to take on world powers, to a non-Sudanese like me it does seem that Bin Laden and the Mahdi had something in common.

When the Mahdi died, his successor, the Khalifa Abdullahi, declared Omdurman ‘the sacred city of the Mahdi’ and built the Mahdi’s domed tomb right by the Khalifa’s house. Like many a Sudanese I have visited the tomb, and chatted with its genial guardian, who told me with delight how his own grandfather from Darfur had joined the Mahdi’s forces who despatched Gordon.

Sheikh’s tomb near Dongola

The Mahdi’s Tomb, Omdurman

The guardian of the Mahdi’s Tomb with his son

Annexe at the Khalifa’s House Museum

Kitchener’s gunboatAl Milekat the Blue Nile Boat Club

We can get a sense of what Omdurman was like at that time from the accounts of an Austrian officer who had converted to Islam. Colonel Sir Slatin Pasha got to know the sacred city well as he was a special ‘guest’ first of the Mahdi and then of the Khalifa. Slatin presents the Khalifa’s rule as tyrannical, with even thehajjto Mecca forbidden, the Mahdi’s tomb substituted as a place of pilgrimage.16From Slatin’s descriptions of the refuse in the streets, it seems Omdurman, unlike Austria, was not a place where cleanliness was next to godliness. Slatin finally escaped after 12 years of captivity, smuggled across the desert to Aswan, where a band playing the Austrian national anthem escorted him on to the postal steamer bound for Luxor.

The Khalifa ruled his Islamic state from Omdurman, until Gordon’s death was avenged by Kitchener. With the killing of 10,000 Sudanese at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898, it was hardly the even playing fields of Eton as British machine guns fired on sword-carrying Dervishes, the technology of Europe wiping out the indigenous tribesmen. Churchill reported that Kitchener thought the enemy had been given ‘a good dusting’;17today there would be calls for a war crimes’ investigation. Sickened by the slaughter of the Sudanese, Churchill’s verdict on the ‘liberation’ of Omdurman was that rescuers had never been more unwelcome.

Kitchener shelled the Mahdi’s tomb from his gunships, and had the remains dumped in the Nile – like Bin Laden, the Mahdi had a watery grave – to prevent the further growth of a cult around his burial site. Barbarically, Kitchener kept the head for a time as a trophy. You can still find one of Kitchener’s gunboats,Al Milek, almost forgotten among the bougainvillea of the Blue Nile Boat Club. Standing by its tiny hulk of metal sheets riveted together, I had to acknowledge the heroism as well as the barbarism of those times.

Khartoum was re-built on a more imperial scale, the streets set out in the form of the British Union Jack. Typically, the city was planned in a suitably stratified manner, with the upper-class residences near the Nile; the further from the Nile, the lower the social class and the greater the heat. The Sudanese were beyond the pale in Omdurman.

Khartoum today is three distinct towns. There is Khartoum proper with its government buildings, rather shabby but not without elegance, and its once grand avenues. Then there is Bahari in the north, both green and industrial, with its remnants of boatyards. And, finally, there is Omdurman, with its extensivesuqs, the metal doors all painted Islamic green, and dusty lanes where the Sudanese mill around in their traditionaltobesandjelabiyahs. By the Nile you can still see the Mahdi’s tomb among the palms.

Khartoum street scene