Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Wilton Square

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

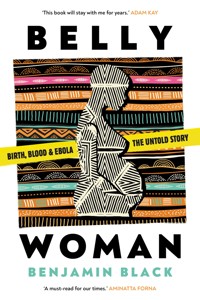

Winner of the Moore Prize for Human Rights Writing in 2023 'This book will stay with me for years.' ADAM KAY, author of This is Going to Hurt 'Black puts a human and profoundly humane face on what it's like to be a doctor.' FORBES 'A brilliant, painful and honest book. Read it.' MARY HARPER, BBC Africa Editor 'Benjamin Black has the most amazing gift for telling a story. I could not put the book down.' VICTORIA MACDONALD, Channel 4 News Courage meets crisis in a doctor's extraordinary true account on the frontlines of maternal healthcare during a deadly epidemic in Sierra Leone. In May 2014, as the country grapples with the highest maternal mortality rate globally, a new, invisible threat emerges: Ebola. Dr Benjamin Black finds himself at the centre of the outbreak. From the life-and-death decisions on the maternity ward to moral dilemmas in the Ebola Treatment Centres, every moment is a crossroads at which a single choice could tip the balance between survival and catastrophe. The tension is palpable, and the stakes are unimaginably high. One mistake, one error of judgment, could spell disaster. Belly Woman is a powerful piece of reportage and advocacy that draws parallels between two global outbreaks of infectious diseases: Ebola and COVID-19. Black's firsthand experience on the frontlines of a global health crisis bears witness to the raw emotions, tough decisions, such as the need to carry out medically-mandated abortions to save lives, and the unwavering dedication that defines the lives of those who step up when the world needs them most. Compelling for readers with an interest in medical memoirs, social justice and humanitarianism, as well as healthcare professionals and maternal health caregivers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 654

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BELLY WOMAN

Benjamin Black

Dr Benjamin Black is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist in London and a specialist advisor to international aid organisations. His focus on sexual, reproductive and maternal healthcare for populations in times of crisis has taken him to many countries. Benjamin has supported the response to various infectious disease outbreaks since the West African Ebola epidemic. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic he provided frontline healthcare to pregnant women and helped develop international guidelines. Benjamin also teaches medical teams around the world on improving sexual and reproductive healthcare to the most vulnerable people in the most challenging of environments.

PRAISE FOR BELLY WOMAN

The winner, Belly Woman, was an extraordinary book on many levels… Black wrote in a moving way… highlighting the voices of women, giving them agency. Their stories were interwoven to powerfully illustrate how a doctor in the field can practice medicine in ways that guide the advancement of global health and human rights. On a different level, he also showed the disparities between the global north and south through a human rights lens, reminding us that these health crises are not a new phenomenon, and that the international community has repeatedly been incapable of protecting human rights.

The Moore Prize for Human Rights Writing Jury

Belly Woman… has the fluidity and compulsion of a novel while providing fascinating insights into frontline action… A powerful story of how medics of all nationalities strived to save lives against the odds… A visceral, harrowing but ultimately life-affirming read.

Susannah Mayhew, LSE Review of Books

This is an important book and I was gripped from the first page. Black beautifully weaves the brutal, true story of fighting to provide maternity care within an Ebola epidemic. May we all be humbled by this book.

Anna Kent, author of Frontline Midwife

From Sierra Leone to London, from 2014 to 2020, Benjamin Black’s account of helping pregnant women in the midst of an Ebola epidemic and a Covid 19 pandemic is heartbreaking and terrifying. Black has done a stellar job of narrating what it is like to be on the frontline of a crisis as it enfolds and then engulfs… The parallels between the two outbreaks are evident, the range of human response not much different: fear, desperation, denial, anger, stoicism, compassion and courage all take their turn. Belly Woman is a must-read for our times. It is riveting, illuminating and humbling.

Aminatta Forna, author of The Memory of Love and The Devil That Danced on the Water

Belly Woman is a jaw-dropping, mind-expanding read, a work of vast compassion and delicate insight into the bracing reality of giving birth in today’s Africa. At times it’s hard to read on without wanting to weep - at the mistakes made and the sheer implacability of death. But like the author himself, you never become numbed or unaffected by the women we encounter, such is their courage and the vividness of Black’s writing in capturing their experiences.

Michela Wrong, author of Do Not Disturb: the story of a political murder and an African regime gone bad

This is an inspirational story of compassion and dedication in the face of a brutal epidemic, and Benjamin Black is the one to tell it.

Leah Hazard, author of Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story’

Brave, moving, and vital. A unique account of battling the Ebola outbreak while providing maternity care in Sierra Leone, and of the incredible women, families, and health workers Dr Black encountered. Read it.

Damien Brown, author of Band-Aid for A Broken Leg

Moving, kind, eye-opening, terrifying and inspirational - this book will stay with me for years.

Adam Kay, author of This Is Going To Hurt

Oh my goodness, I could not put the book down. Benjamin Black has the most amazing gift for telling a story. Belly Woman transports you to Sierra Leone, to the compounds, to the hospital wards, to the villages ravaged by Ebola. As Dr Black and his colleagues fought for better care and to improve maternity services, you feel every drip of sweat inside their PPE, you hold your breath as they too wait for the newborn to cry, and you weep at every life that could have been saved but for the lack of facilities and equipment.

Victoria MacDonald, Health and Social Care Editor at Channel 4 News

This is a work of nonfiction. It reflects the author’s recollections of memories and experiences. Some names and characteristics have been changed; some conversations have been recreated and certain characters may be composites to protect the privacy of the people involved.

Belly Woman is a title created by the author. It has no specific meaning in English or Krio. The pronunciation, ‘be’leh ’uman’, is the Krio word for a pregnant woman.

First published by Neem Tree Press in 2022

This edition published by Wilton Square in 2025

Wilton Square Books Ltd

29 Wilton Square, London N1 3DW

United Kingdom

www.wiltonsquarebooks.com

Copyright © Benjamin Black, 2022

Cover Copyright © James Jones, 2022

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-911107-56-9 Hardback

ISBN 978-1-911107-57-6 Paperback

ISBN 978-1-806770-41-0 Ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address above.

Printed and bound in the UK

‘I was devastated and restless when I looked at the pregnant women.’

– Fatmata Jebbeh Sumaila, Sierra Leonean midwife and colleague

CONTENTS

Map of Sierra Leone

Diagram of an Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC)

Acronyms

Author’s Note

Person, Position and Purpose

Part 1

1: Birth Complications

2: Pre-Departure Planning

3: Gondama

4: So Many I Stopped Counting

5: Medical Roulette

6: No One Laughs at God in a Hospital

7: Lightning Strikes

8: Below the Surface

9: Unprecedented

10: Kailahun

11: State of Emergency

12: Invisible Insurgents

13: Two Young Brothers

14: Transmission

15: Exodus

Part 2

16: Life in Limbo

17: Same, but Different

18: Belly Woman

19: Bandajuma

20: Pregnancy Prevention

21: The Cavalry Arrives

22: Tonkolili

Interlude

23: Full Circle

Part 3

24: A New Beginning

25: Bomb Scare

26: The Third Delay

27: Christmas

28: A New Year, A New Project, Another Chance

29: Far From Perfect

30: Not Normal

Afterword

Acknowledgements

End Notes

ACRONYMS

BBC

British Broadcasting Corporation

CAR

Central African Republic

CHO

community health officer

DHMT

district health management team

DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

DRC

Democratic Republic of Congo

ETC

Ebola treatment centre

GRC

Gondama referral centre

ICU

intensive care unit

IV

intravenous

MOHS

Ministry of Health and Sanitation

MSF

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders

MTL

medical team leader

NGO

non-governmental organization

NHS

National Health Service

OC

operational centre

OCA

operational centre of Amsterdam

OCB

operational centre of Brussels

PC

project coordinator

PCR

polymerase chain reaction

PHU

peripheral health unit

PPE

personal protective equipment

RCOG

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

SOAS

School of Oriental and African Studies

TBA

traditional birth attendant

UNFPA

United Nations Population Fund

WatSan

water and sanitation specialist

WHO

World Health Organization

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Person, Position and Purpose

I was in Sierra Leone in January 2020, when I read about a new illness reported to be spreading in Wuhan, China. It was my first time in the country since March 2016, where this book ends.

I had been thinking a lot about epidemics, as I often do. A phrase had been playing in my mind as I travelled: with a flick of the wrist, we are brought to our knees. This was my feeling about the 2013–2016 West African Ebola epidemic.

Like dust from a rug when it is shaken, we are thrown tumbling through the air. How nature reminds us of our frailty; her power immense, our control limited.

In that same month, January 2020, I had published, with two colleagues, Gillian McKay and Alice Janvrin, an advocacy paper for sexual and reproductive health rights to be integrated into epidemics. We had gathered data and interviews from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where another Ebola epidemic stubbornly continued to fester. We had questioned whether any lessons had been learnt. Was there hope for the next epidemic?

I first went to Sierra Leone in June 2014, deployed as an obstetrician and gynaecologist with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). It was to be the beginning of a journey like no other. I returned home, in October, several months into that journey. As I jogged around the leafy streets of north-west London there were visions of the Ebola camps coursing through my mind, along with the memory of two young brothers I had promised not to forget.

It was then, that I made a personal commitment to write this book. I began collecting these memories eighteen months later, in April 2016, as I re-entered the UK National Health Service (NHS).

As 2015 drew to a close, the embers of the Ebola outbreak of West Africa continued to glow. There were already committees, conferences and congratulations underway; conclusions being drawn; knighthoods bestowed; medals and prizes awarded. The epidemic simmering, the underlying causes remaining unresolved, and the world’s attention predictably shifting.

I wrote Belly Woman to open the door to a battle for life many people are unaware of. I want to take the reader behind the Ebola headlines to meet the people on the ground, so they can face the dilemmas with them. My hope is to add to the narrative of one of the greatest public health crises in history, to explore what it is to be pregnant with limited access to emergency care, and to consider the choices we make in extremis. This is a raw account, at times distressing. There are descriptions of suffering, medical procedures and emotional turmoil (I advise caution, or guidance from a friend, for readers with pregnancy-related trauma). But it also depicts moments of joy, camaraderie and the hope for better.

The intertwining circumstances which fed and led to the West African epidemic demand far more analysis than is possible here. This book is a taster; a small addition to the wealth of papers and texts available on the epidemic, humanitarian systems and maternal healthcare.

Contexts change, policies are revised and, sometimes, lessons are learnt. Our approach to Ebola virus disease has changed too. Since the times described in this book, there have been effective vaccines produced and large multidrug trials undertaken, discovering treatments and cures. Perhaps, by the time you read this, a simple pill will solve the ailment. Progress, though, does not equal forgetting. The emergence of COVID-19 brought us back to the start: the search for solutions renewed, ethical conundrums unanswered and our faith in humanity shaken.

This book is not a critique of Médecins Sans Frontières, the governments of affected countries or the international response. I have been honest in sharing my opinion, and accept that, inevitably, not everyone will agree with my point of view. This is an unaffiliated piece of work, written in my own time. This is my story, my experience and my reflections. It is through the nature of being my recollections that I play the central character; in reality, though, I was a peripheral figure to the events witnessed. Above all, it was the people who lived in the countries where I was welcomed who worked longest and hardest, and it was they who paid by far the highest price for doing so.

I am acutely aware that I am a man in a high-income country writing about maternity care and events in African countries. There is no intention for my voice or perspective to represent or replace anyone else’s, say, a woman from a rural village in Sierra Leone. While I was writing Belly Woman, the humanitarian sector was reflecting on its structures and how they perpetuate racist and colonial approaches to the work. Though not the focus of this book, the events described took place in an era when aid work was in need of reform. The terminology used is reflective of the period of writing. International staff, also referred to as expatriates or expats, lived and socialized together. The time working abroad was called a mission and the location was always the field. A part of my journey has been the growth in my awareness of the inequalities and imperfections of the modern humanitarian approach.

In writing this memoir, I have balanced the risk of being accused of playing the ‘white saviour’. If I have presented myself as that person – possessing a superiority complex, patronizing tone or patriarchal stance – I apologize for my naivety and for any offence caused, but not for recording these events.

Some names have been changed and some events altered to maintain confidentiality and avoid collateral damage. Names of patients, if given at all, have been changed as have identifying and medical case details, with the exception of those already in the public domain. Memories are my own; no doubt they are far from perfect. Time and trauma can play many tricks on the mind, and, where these have resulted in errors, I take full responsibility and apologize.

In statistical terms, maternal deaths are often described as being the tip of an iceberg. For each death, approximately thirty women are severely or permanently disabled through complications of pregnancy. A large mass hidden below the water’s surface, but no less significant.

Similarly, in writing this book, I could not tell every patient’s story, nor do justice to all the people with whom I had the privilege of working or interacting. For each individual, there are at least another thirty, and where names or actions are not present in the pages that follow, it is no reflection of worthiness, but merely the result of the limitations of my mind and the confines of book writing.

The people and organizations I’ve written about faced stresses and circumstances at the extremes of human experience. Where my writing exposes failure, the failure is mine for inadequately portraying the complexities and nuances of the situation. I remain a proud member of the MSF movement, fiercely supportive of their incredible work, while accepting that they (which includes me and my actions) have faults.

Crises expose our resilience. The change in circumstance lays bare our personal and collective investment in social structures, trust and access to resources. It is no accident the Ebola epidemic swept through communities in the countries with some of the world’s highest maternal and child death rates. It is no coincidence the worst-affected populations in epidemics are in neglected regions, conflict-affected areas, the poorest and most crowded districts. The disease moves within human suffering. The spread of disease is symptomatic of the status quo. Whether it be cholera in famished Yemen, diphtheria in an overcrowded Rohingya refugee camp of Bangladesh, or hepatitis E spreading in the unsanitary conditions of the displaced South Sudanese, the illness is opportunistic to the conditions we have handed it.

Through 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic surged, I worked as an obstetrician and gynaecologist in London, joining my colleagues in the struggle to provide complex maternal healthcare to women with COVID-19, women without, and the many for whom we had no result, all while negotiating safety for health workers and pregnant women alike. In the evenings, I supported international humanitarian responses to the pandemic, considering dilemmas from across the world. How will women with pregnancy emergencies access care if all facilities shut down? How can we treat rape survivors? What if our supply of contraception burns out?

Over a hundred epidemics unified into one, the COVID-19 pandemic overwhelmed in spread and volume. As the dominoes fell, I asked, Could we have predicted what was coming?

When Ebola struck West Africa, the international community should have done better.

COVID-19 is not Ebola, but, like a circus mirror, there is enough to recognize within its distorted reflection.

Through my public catharsis, I am sharing the journey and decisions of the past. I hope you, the reader, will join me in questioning the events, their roots and the ramifications for the present. To ask: What does it mean to be humanitarian? How can we strive to prevent unnecessary deaths and needless suffering? Is it possible to avoid repeating previous errors?

Part 1

1: BIRTH COMPLICATIONS

GONDAMA, SIERRA LEONE

JULY 2014

The woman is lying on the floor outside the maternity department; her large pregnant belly slopes to one side as her back arches, face muscles clench and a violent, jerking convulsion resumes. It’s past midnight, the air is warm and humid, hanging heavily around us. The two men who had squeezed her on to the back of their motorbike stand silently, staring; everyone is staring.

If this is an eclamptic seizure, her life, and that of her unborn child, can be saved. Take her inside the hospital, begin treatment and deliver the baby. The husband is watching us with red, pleading eyes. Every day, women come with emergencies; they come to us trusting we will treat them. But now we stand, frozen, contemplating the woman and the life lying on the floor in front of us.

Blood is round her nose and mouth.

‘She fell forward on to her face with the first seizure,’ says the weary looking husband.

Around the world, a woman dies every two minutes from a pregnancy-related complication, eclampsia being one of the leading causes. Virtually all maternal deaths are preventable. It is the reason we are here, and why she has come to us. Her death will be tragic, not only for herself and her children, but for her whole community. It will mean the loss of all the functions she, as a woman, brings to society.

Almost all maternal deaths occur in poor countries, affecting the most vulnerable, with the least resilience. A disparity so large is humiliating in our modern world, representing social, political and economic failures. Will we fail her, and her family too? An unseen force is holding us back; the life-saving medicine is behind the door, in a room with other women in labour.

The seizure stops, her arms flop to her sides and her chest rises with rapid shallow breathing.

‘What is your address?’ a nurse in green scrubs shouts from several metres distance to the husband. Small beads of sweat shine on her forehead, reflecting the headlight of the motorbike.

They have travelled far. Their journey began in a town six hours away – a town with a recent cluster of Ebola cases. If this is Ebola, it changes everything.

Ebola, or Ebola virus disease, strikes fear into the public and healthcare workers alike. In 2014, no vaccine existed. There were no medical treatments available.

There are six species of Ebola virus*; the most lethal is the Zaire strain, which was deadly in approximately 60 to 90 per cent of cases. Zaire ebolavirus was responsible for the West African epidemic. Initially transmitted from an animal reservoir, probably from non-human primates or bats, into a human host, the disease spreads efficiently from person to person via infected body fluids. The incubation period is thought to last up to twenty-one days. Initial symptoms are general and non-specific: a fever, aching joints, weakness. Similar to other common ailments, such as malaria or influenza, it is easily missed. The virus infects the cells lining our blood vessels, organs and intestines. As our immune system tackles the onslaught, our body becomes the battlefield. Blood leaks from the vessels. Bowels seep fluid. Inflamed organs become painful and dysfunctional. The virus is deadly, but so too is the body’s counter-attack, destroying itself in the effort to purge the invader. Over time, the condition develops into more severe vomiting and diarrhoea, which can progress to multiple organ failure and death.

As disease severity worsens, the infected person becomes increasingly contagious. By the time of death, their body is encased in their virus-packed excretions of urine, faeces and sweat. Those caring for the sick, offering comfort and washing their bodies, tread a perilous path. The risk of infection for healthcare workers in West Africa was up to thirty-two times greater than it was for the general public.

Her husband is becoming anxious. Why the questions? Why are we not rushing to save his wife and child? He gently places a folded cloth under her head and strokes her face. He brought her to us for help. Her situation is desperate. All he sees are the silhouettes of nurses, midwives and a doctor, conspiratorial and whispering.

With only one capable laboratory in the country, it will take over twenty-four hours for an Ebola test result to be returned. Without treatment for her pregnancy complications, she will die. Inside, there are tight rows of women sleeping under mosquito nets, next to babies bundled in brightly patterned lappa. In the daytime, breast milk, blood, sweat and soiled bedclothes mix as the women congregate, sharing advice, joy and condolences.

An Ebola epidemic had been declared in March, across the border in Guinea; it had spread to Liberia in April. In Sierra Leone, there had been rumours of suspicious deaths for months, but no confirmed cases. Six weeks earlier, on 24 May, a pregnant woman had been admitted to Kenema Government Hospital’s maternity ward because she was having a miscarriage. She was also feverish, with vomiting and diarrhoea. The pregnant woman had left a local health centre to seek further care at the hospital. On that same day in May, a forty-two-year-old mother of two, Mamie Lebbie, sought care at the same local health centre; she was suffering watery diarrhoea. Mamie came from Kailahun, in the south-east, near the Guinean border. She was suspected of having cholera, triggering an alert to be sent to the district surveillance team. On the advice of Sierra Leone’s only virologist, Dr Sheik Humarr Khan, an urgent blood sample was sent to his laboratory in Kenema. Another woman, inside the Kenema Government Hospital, was also identified as having symptoms suggestive of Ebola; she too had come from the same local health clinic. The following day, all three women returned positive Ebola blood results. These women became the first confirmed cases of Ebola in the country.

They all had links to the funeral of a highly respected female traditional healer from Kailahun. The healer had been treating unwell people from both sides of the border, ultimately leading to her infection and death on 30 April. The traditional rituals of washing and touching the deceased body followed, so that her death and burial were linked to some 365 Ebola deaths and were key in contributing to the onwards spread, resulting in 14,124 infections and 3,956 subsequent deaths in Sierra Leone. But not Mamie Lebbie or the pregnant woman; among the country’s first confirmed patients were their first two confirmed survivors.

In the weeks that passed since those Ebola results there were more confirmed cases, and further spread into the country. Healthcare workers were on alert. Vigilant to ask, could this be Ebola?

A light breeze momentarily breaks the tension. The triage paper used for checking Ebola symptoms has become soft with the rainy season’s moisture. Glances pass from one person to another, piercing through the night air. The woman lies unconscious. Should she come inside maternity, or stay outside? Eclampsia or Ebola? If the diagnosis is incorrect, by the time it is realized, the damage will be done.

*

The scene was already set; the actors of a peripheral state government, egotistical international organizations and an impoverished population were in position. The stage had been built on a history of pillage: slavery, colonialism, civil war, corruption, plunder and disenfranchisement. The Ebola epidemic might have begun in December 2013, but the legacy of injustice stretched back centuries. Seeds of mistrust had been planted in a collective memory, with ample time for the roots to take hold.

As the sick attended health facilities and traditional healers for help, their misdiagnoses and the touching, and spreading, of infected body fluids, together with the chronically under-resourced government institutions, provided fertile ground for the amplification of disease. Although ten countries were affected, it was Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia that bore the greatest burden of the Ebola epidemic. In total, there were 28,652 cases reported, including 11,325 deaths – although the full extent is certainly higher, and will never be known. It led to the near breakdown of a vulnerable and weak health system. The resulting deaths from the loss and fear of healthcare possibly outstripping those directly from Ebola .

Ebola lifted the curtain on a performance that had been playing out for decades. And the audience could watch, participate or turn away.

_________

* The six identified species of Ebola virus are each named after the place of their discovery, followed by ‘ebolavirus’, the genus name, similar to a first name and family name in people. Four of the species are known to have caused disease in humans. The sixth species was identified in 2018, in Sierra Leone, but it is not known if it causes illness in humans or animals.

2: PRE-DEPARTURE PLANNING

CAMDEN, LONDON

MONDAY, 16 JUNE 2014, 7.30 A.M.

I am on the floor, sitting on top of a bag I have spent weeks deliberating over. I try to squeeze another book inside the rucksack. No matter how I manoeuvre myself, or the zip, it won’t close. My parents look at the room; clothes and belongings are sprawled across the floor, with me in the middle.

‘Have you packed some snacks, for when you arrive?’ asks Mum, trying to sound relaxed.

I glance up from my position on the bulging bag. My face says it all: Do. Not. Talk. To. Me. They retreat.

My parents had travelled down from their home in Manchester to bid me farewell. I’m thirty-two years old, a doctor, their youngest child and only son, pausing my career, and all our lives, to pursue my ambitions in the humanitarian sector.

Soon, I will begin a journey to Brussels for briefings from MSF’s Operational Centre (OC). From there, I will continue to Sierra Leone. MSF has hundreds of projects, working in over seventy countries, providing emergency and medical assistance. I had spent days reading their reports, (self-critical and reflective); and evenings reading the testimonies of their field workers, (emotive and exhilarating). I wanted to be a part of their independent, humanitarian, medical identity, getting to the places where aid was needed most.

MSF has a complicated organizational structure. It is split into five separate sections, each with its own culture and operational priorities; they are, however, united under a single manifesto and logo. The sections are named after the cities where their headquarters reside: Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Geneva and Barcelona. The Operational Centre of Brussels, or OCB, had been present in Sierra Leone for many years, and their maternal and child health hospital was a jewel in their crown, both in terms of size and the numbers of patients treated.

The project was called the Gondama Referral Centre, or GRC. It was located close to Bo city, the largest city after the capital, Freetown. I was aware of the project, as it was a well-known destination for obstetricians working with MSF.

I had sat in a stuffy London pub on Great Portland Street with another obstetric doctor, Pip, who had spent two years out in the field with MSF, six months of which were in GRC. ‘You’ll be fine,’ she’d told me, as she recalled massive haemorrhages, tropical infections and near-death experiences.

In the months before I was sent to GRC, a strategic decision had been made at the Brussels headquarters for it to stop providing maternity care. Child healthcare was to continue, and their interest in Lassa fever, an endemic viral haemorrhagic fever in the area, was increasing, but maternity would end in June 2014.

In May, the World Health Organization (WHO) had released an updated report on global trends in maternal mortality. Sierra Leone had the highest ratio of women dying to live births in the world. According to MSF’s own calculations, GRC had resulted in an over 60 per cent decrease in women dying from childbirth locally and was providing around a fifth of all caesarean sections in the country. Women from a geographical area spanning over a third of the country travelled there for life-saving interventions and surgery. This project was important. But, at some strategic level, maternal health was not important enough.

Internal organizational pressure led to a swift U-turn and a decision at the eleventh hour to continue obstetric services, though the longer-term future of the facility remained uncertain. Suddenly, a service that had been facing imminent closure had openings for obstetricians which needed filling fast. I was called and asked if I could be there within two weeks.

I had built my ambitions on the stories and experiences of civil wars, earthquakes and refugee migrations. I wondered if I was selling out by going to a stable development setting, rather than a fragile humanitarian crisis. An awareness was rising up inside me, though there was a lot of talk of ensuring that reproductive health, including access to emergency obstetric care, was available in every humanitarian response, but the reality was very different. Rather than being prioritized, it was often substituted with proxy activities, leaving limited demand for an obstetrician.

Through medical school, I had studied with the intention of becoming an aid worker, considering specialties with this in mind. A decade earlier, I spent several months working with refugees and migrants crossing from Myanmar into Thailand. The maternal health needs were striking. Women came to us with late complications, or needing a safe place to give birth. Sometimes they arrived after delivering in the jungle, with horribly infected babies. Every day, women would attend with complications of backstreet abortions; without access to contraception or legal abortions, they turned to any willing provider. Dire poverty left many with little choice. Sex was an industry, a way to procure goods, to survive, to feed children or keep a job in a saturated labour market. Women, often girls, arrived bleeding, infected and internally damaged. Despite all the harm to the woman, the botched abortion could be distressingly unsuccessful; often the pregnancy continued unaffected. It was here, as a twenty-three-year-old student, that I concluded obstetrics and gynaecology was my path into humanitarian assistance. The needs were vast, and I was drawn to the deeper questions of how to respond beyond medicines and surgery. The specialty offered everything: it was broad enough to keep me well informed on general medicine, while specialized enough to be of value to a population in crisis.

I took further studies and read book after book on how development and aid agencies had entered into situations with good intentions, but poor outcomes. I learnt about the history, evolution and errors of major aid organizations and how their past shaped their work today. Rather than deterring me, this information made me even more curious. How could we keep getting it wrong? Lessons identified were often called ‘lessons learnt’, but, as I continued to read, this seemed less convincing. My desire to be part of the humanitarian system grew, as my questions of its effectiveness flourished alongside.

Towards the end of March 2014, Ebola virus was confirmed in Guinea*. MSF had assisted in the initial suspicions and identification of the disease. The virus had taken an unusual and concerning course, entering urban areas and crossing international borders – first into Liberia in April, and then Sierra Leone in late May. I had been following the story, but held no desire to be involved in the Ebola response. I was unfamiliar with the disease, and did not see how it could relate to my role.

The week before I was due to leave, I spoke on the phone to Severine, the obstetrics and gynaecology adviser for MSF-OCB. She was out in GRC at the time, and she reassured me that there had been no Ebola cases in the area of the project, the outbreak remaining contained in the east, around the Guinean border. The general consensus was that Lassa fever was of much greater concern, in terms of exposure and risk. I left for Sierra Leone knowing Ebola was there, but without any genuine anticipation that I would encounter it. In retrospect, it seems ridiculous; the epidemic, as we know now, was unprecedented. But, in early June, we had a dragon under our feet only just beginning to awaken; the ferocity and fire were yet to come.

Standing outside the MSF Operational Centre of Brussels, I felt like I was about to enter a special society. Through those doors, huge decisions were made on access to life-saving interventions, often with uncertain consequences. I was about to walk into one of my textbooks, words and thoughts lifting off the page to become people and discussions in meeting rooms. This was the inner sanctum of one of the most recognized non-governmental organizations in the world, a searchlight shining out to me through a haze of humanitarian scepticism.

People rushed around, smiling, chatting, shaking hands. A dynamism filled the air; the energy was a vibrant, and firm: ‘Let’s get the job done.’ In a moment, I had moved from outsider to insider. I wanted to get the job done too.

As the administrative team sorted out my visa applications, a woman around my age came and joined me at the desk. Alice was also heading to Sierra Leone; she was flying out as part of the first MSF Ebola response team in the country. I was impressed by her calmness. There was no shred of fear on her face, just a concern about whether she could fit all the dolls and teddy bears in her bag for the children she would work with. Alice was Danish, a psychologist, and her role was to provide psychosocial support to survivors and families affected by the outbreak.

‘I’m an obstetric doctor, heading out to GRC,’ I told her.

She squinted her eyes. ‘So you’re a very important person then.’

I thought it was a strange comment from a woman who was about to head into an Ebola outbreak. I shrugged, ‘We’re all important people’.

Making my way around the office, each person I met gave me more papers to read, documents to sign and encouragement that I was joining a great project.

Severine, the obstetrics and gynaecology adviser, had travelled into Brussels especially to see me before my departure. We sat together at a long desk, the walls on either side decorated with large maps and magazine-style pictures of refugee camps, MSF operating theatres and striking faces staring into the lens.

Severine spoke modestly, with an air of understated competence. ‘You can see the full obstetric textbook in one shift,’ she said. ‘That’s how it is, in the field.’ She had worked in many MSF missions, including GRC, before taking the headquarters position. She had the stories and understanding of being a doctor from a high-income country working in a resource restricted setting. ‘Obstetrics in the usual MSF settings and obstetrics in the UK are separated not only by geography, but in nature too,’ she said.

I already knew I would be dealing with cases and carrying out procedures I had never had to perform before, because the situations leading to the necessity for such procedures were unheard of in London. Gaining another ten years’ experience in London would be no guarantee of exposure to such operations.

Severine shared her experience of performing obstetric hysterectomies, repairing ruptured uteruses and the technique of replacing blood directly from a haemorrhaging patient back into the same patient’s body during surgery. ‘I brought these for you to see.’ She pushed a small pile of textbooks towards me. ‘These are my bibles in the field. If you’re faced with an unfamiliar situation, they can be lifesavers.’

We discussed working alongside local and international colleagues, differences in work ethics and expectations, and ways to manage the inevitable tricky situations arising from the power, economic and cultural dynamics at play.

As we spoke, I was increasingly reassured that I had backup, but I also felt trepidation. I was entering into a mixing pot of more than just complex obstetrics.

‘The national staff are still feeling quite sensitive about the decision to close obstetrics at GRC,’ Severine said. Her voice changed a notch. ‘Some staff had already taken new jobs when MSF reversed the closure. These people, they thought they were losing their jobs till a couple of weeks ago; many are the breadwinners for the family. It has caused quite some loss of morale. It damaged our relationship a bit. The expected closure has also impacted our patient numbers, but I think the news will travel and they will return.’

‘So obstetrics will stay?’ I asked.

‘This decision was last minute. I believe it will be temporary, but maybe we can change their minds.’

I was astonished that ending obstetric activities was still on the table, given the maternal health indicators. I wondered how the Sierra Leonean staff would relate to me while their long-term future remained uncertain.

‘You need to know about Lassa fever,’ said Severine, moving the briefing forwards. ‘It’s a major concern for the project, particularly on the obstetric side, where we’ve had several staff infections.’

I was asked to complete forms in case I caught Lassa fever and medical evacuation became necessary, or if I had symptoms after my mission was over. I signed that I understood the protocols of infection control, and was given more to read about the disease, its symptoms and ways to reduce the risk.

Lassa fever is transmitted to humans in the urine and faeces of the multimammate rat*; strict measures were in place to keep the rodents out of our work and living areas. Once infected, the disease can be passed between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids – hence, a clear risk of exposure during childbirth and major surgery. Lassa fever and Ebola share many similarities, but there were also important differences. Lassa fever was endemic in the region; it had been a part of the differential diagnoses for many years and was particularly recognized as a complicating factor leading to death in pregnancy. The majority of people who contracted Lassa fever displayed no symptoms or complications at all. However, for those who did become unwell, there was a 20 per cent risk of death. Crucially, there was an antiviral medication, called ribavirin, which, if given early and appropriately, appeared to be effective against the disease.

As my day of briefings drew to an end, I felt ready. The time was now. This large, busy and chaotic office had opened its arms to me and I wanted to be embraced. In a short day, I had met many people, in some cases for just a few minutes, who would cross my path over the years to follow in ways I could not anticipate.

‘We are going to watch Belgium play in the World Cup,’ said Severine, gesturing to a group of her colleagues. ‘Join us?’

We all headed over to an open-air square, where we drank and chatted until the game began, shown on a huge screen. When Belgium scored, the crowd cheered and spontaneous dancing broke out. Beers were thrown up in the air in celebration. A real sense of optimism surrounded me and I breathed it in as much as I could. Summer was in the air and everyone was relaxed.

A woman with a short blond bob haircut sat next to me. ‘I’m Liesbeth,’ she said. ‘I hear you’re heading to GRC.’

News travels fast, I thought.

‘I spent over a year working there,’ she explained. ‘You’re going to like it; it’s a great first mission. Very social, low-security setting and beautiful country.’ Liesbeth was looking at me, but I felt her mind was seeing the past.

Her reminiscence was broken as another round of beers arrived at our table.

‘Proost!’ said Liesbeth, and we clinked our drinks. ‘I’ll be joining you out there next week. Last time I was there, some of our colleagues caught Lassa fever. There was a lot of stress then.’ Liesbeth’s voice was gentle, but I sensed a flicker of emotion as she recalled the challenges of trying to get the correct safety measures in place. ‘The staff needed to feel they were protected. They were asking for a lot and we really tried, while we could see standards were not being maintained.’ It was clear she had had a difficult time, but also, she had come through it with solid achievements and character. ‘So, I’ll be lending a bit of extra support to the project, just for a few weeks.’

‘Great – I’ll be waiting for you,’ I said, feeling glad there would be a familiar face joining me within my first week.

Drunk, I wobbled my way back to the hostel. I spent the rest of the night trying to download textbooks on tropical medicine, messaging friends and staring at my bag which needed to be totally repacked.

The next day, I met Alice, the psychologist, in the boarding queue for the plane to Freetown. On arrival at Lungi International Airport, about seven hours later. There was little to suggest the threat of Ebola other than a couple of small posters pinned to the wall at immigration. Alice and I spotted a tall bearded guy with an MSF-logo holdall bag. Frederick was an experienced water and sanitation specialist (usually referred to as a ‘WatSan’) who was also heading to the border with Guinea, where the newest MSF Ebola Treatment Centre was due to open. The three of us continued our journey together.

Lungi airport sits on a peninsula facing the capital, and the quickest way to reach Freetown is by ferry. By the time we arrived at the jetty, the sun was already beginning to set. The warm salty air smelt like holidays, women walked along the beach with baskets balanced on their heads and children pranced around in the sand. It was an idyllic scene.

Frederick and Alice were familiar with the routine of arriving at a new project, but, for me, everything was new. We got to the house where we were to spend our first night in Sierra Leone and were met by an administrator, who gave each of us a mobile telephone and an envelope with instructions and security rules. We left our bags and together headed to a local restaurant, where we ate rice with dried fish as we discussed what the next few weeks might hold for us. They both appeared relaxed, and there was no discussion of Ebola impacting the work I would be doing. After that night, we were heading to two very different realities, or so we thought. That was Wednesday evening, 18 June.

_________

* The alleged index case of the Ebola epidemic has been traced back to December 2013, in Guekedu, Guinea. However, the first confirmatory tests were in late March 2014.

* The multimammate rat (which isn’t actually a rat) is a reservoir for Lassa fever. The rodent appears similar to a mouse or small rat. Once infected, the rodent excretes the Lassa virus, potentially for all its life. They live close to humans, scavenging leftover food, and breed rampantly.

3: GONDAMA

FREETOWN, SIERRA LEONE

THURSDAY, 19 JUNE 2014

I woke early on Thursday morning, hot and sticky. I pulled myself up and out from under the mosquito net and took a cold shower. I was to be interviewed by a representative from the Ministry of Health to gain my licence to practise medicine in Sierra Leone. I wanted to make a good impression and had packed long khaki trousers, a smart sky-blue shirt and black leather shoes specifically for the interview. It wasn’t yet 9 a.m. and I was already sweating. Evidently, I had chosen a poor colour for concealing perspiration. I looked terrible, with sweat patches across my shirt. I focused on my breathing to try to keep calm, fanning myself to keep cool. None of it helped much.

I sat alone in the stuffy waiting room; two secretaries sat opposite me, typing and sweating. Eventually, I was called into the representative’s freezing air-conditioned room. The air hit me like an ice wall – at first a relief, though I soon felt hypothermic. The representative was a formally dressed, slight and skinny man. He sat behind a large heavy wooden desk, which, by comparison, made him look even skinnier and smaller. Peering over his glasses, he seemed to size me up and gestured for me to take a seat. He rustled through an application form, which had been completed on my behalf by the MSF in-country team. He looked at me, said nothing, then looked and rustled through my papers again.

‘What is the purpose of your time in Sierra Leone?’

‘I’m here with MSF; I’ll be working at the obstetric referral centre.’

His eyebrows moved together, forming a cross of creases between them. ‘I see you have a master’s degree in conflict and development. What’s that got to do with your time here?’

I paused, feeling the thin ice below me as I uneasily manoeuvred for an answer. I began trying to broaden the conversation, inviting him into subjects such as the long-term impact of conflict on development and sustainable healthcare. This wasn’t what I had been expecting.

‘Well, I don’t see how you can work here.’

My heart pumped hard and my hands became clammy as I felt my stomach open up. I was going to be denied a permit and sent home. I didn’t even understand why, except that he was unimpressed by my choice of studies.

‘But I’m a doctor. I’m trained in obstetrics and gynaecology; you have a lot of women dying here.’

He looked at me again, then at my papers and back to me.

‘You’re not a qualified doctor.’

We looked at each other across the large wooden desk. I was confused.

‘Can I see those papers?’ I asked.

The only qualification listed was my master’s degree. Desperation lurched within me. I opened my bag and pulled out my own copies of my medical certificates, explaining each one.

The man’s face softened as he leafed his way through the pages. He looked sternly at me again. ‘You did not fill this application yourself.’

The atmosphere relaxed and we continued our conversation in a friendlier way. He stamped my papers and signalled our time was up.

I returned to Alice and Frederick in the waiting car, where I threw off the formal gear, returning to the comfort of my shorts, T-shirt and flip-flops. ‘Let’s go!’ I said.

We planned to drive directly to Bo, some three and a half hours away, where I would disembark and Frederick and Alice would continue for another four hours or so to the north-eastern border town of Kailahun. The road out of Freetown wound through green hills, the steep slopes sweeping down to the Atlantic Ocean. We glided along the tarmac, past little clusters of stalls, shacks and small groups of women with children, standing around large wooden mortars, pounding rice with long sticks. I drifted in and out of sleep in the hot car, vaguely aware of the murmuring voices in the front, as Alice and Frederick talked about the project they were heading to. I opened my eyes, registering the towns we were passing through, occasionally catching a blast of West African pop music from outside. Finally, we pulled off the highway into a large walled compound. Flying overhead was the iconic MSF flag: a sketch of a figure standing, arms and legs apart, drawn from red and white diagonal lines.

A tall Sierra Leonean man approached our car. ‘Welcome to Bo Base!’ he said, as we all got out. I offered him my hand to introduce myself, but he just looked at it and smiled. ‘We don’t shake hands here.’ He then demonstrated the alternatives – either putting a right hand to the left chest or tapping elbows. At first, I thought perhaps this was a cultural variation to handshaking, but it was my introduction to the no-touch policy. We were directed to a Veronica bucket – a large bucket mounted on a wooden stool, with a tap fixed near the base and a bowl underneath. ‘Wash your hands with the chlorinated water before entering any buildings, then rinse the tap before turning it off,’ the man said.

At first glance, Bo Base looked like a garage: a large tarmac courtyard, filled with white Toyota Land Cruisers. Men stood around, hosing down the Land Cruisers and checking their tyres.

We were directed through a side-door into a large concrete building and up a dark, narrow staircase. We climbed up the steep incline, at the summit it opened up to a large atrium. There were couches arranged in a big horseshoe shape, and scattered around the perimeter were tables, chairs and electric fans. Several offices and smaller meeting rooms surrounded the main gathering space, which was comfortable and welcoming, filled with natural light from the many windows.

The three of us made our way over to a long table where a group of people were eating lunch. Every day, new expats passed in and out of Bo Base, either coming to GRC or on their journey to Kailahun. We joined the group and began investigating the food situation. I felt awkward, uncertain how my vegetarianism would be viewed. I picked at the cold pasta salad, trying to discreetly remove the pieces of pink meat. Gradually, everyone introduced themselves: logisticians, administrators, medics. Two women marched in together, speaking in rapid French. It was evident from their purposeful manner that they were in significant positions. One was tall and statuesque, as if made of alabaster, and she came and joined us at the table, while the other disappeared into a side office.

The woman introduced herself as Kathleen, cocking her head and smiling at the three new people at the table. As she ate her lunch, she told us she had come to GRC in a senior nursing position, but had recently changed her role to ‘Ebola focal person’, given the uncertain situation in the country.

Alice looked at her for a moment, took a deep breath and announced, ‘So, you’re a very important person now’.

Kathleen stopped eating. ‘What does that mean? When I was a nurse, I was very important.’

I smiled, recalling my own first meeting with Alice.

The other woman came back into the room from the side office. She didn’t sit with us, but headed straight to one of the faux-leather couches and pulled out a pack of cigarettes, lit up and took long hard drags. She said nothing, just looked straight into the smoke rising in front of her face, scrying for something. She had a sharp penetrating stare, and her eyes narrowed as she turned to the table.

‘Barbara, this is Benjamin, our new gynae,’ said Kathleen.

From the couch, Barbara motioned for me to come over and join her. She introduced herself as the project coordinator, or PC, responsible for security and the daily functioning of the project. She reminded me a bit of Dalia, my oldest sister; they had similar long brown curly hair. Her intense mannerisms were similar too, and in this I found comfort. I was on familiar ground.

There was no time for small talk: ‘I’m heading to the hospital in fifteen minutes,’ she said. ‘You can join me. I’ll give you your briefing over there.’

I said goodbye to Alice and Frederick, who would be continuing their journey east, and climbed into the back of a Land Cruiser with Barbara and Kathleen. GRC was about six miles from Bo, but the roads were in such a terrible condition that the journey took about thirty minutes. I had arrived at the beginning of the rainy season; these muddy potholed roads would become increasingly waterlogged and, at times, impassable.

I gripped my seat as I was jolted and thrown about, while Barbara continued talking, unaffected. ‘You’ll be replacing Crys,’ she said. ‘She’s been here for three months. She works with two other gynaes: Marlon, the team leader – he’s been in the project a long time; He’ll soon be replaced. He –’ Barbara hesitated – ‘he’s very tired. And then there’s Mamadou, from Guinea. He’s working on his English. You’ll have to speak slowly. Mamadou’s going to take over the position of team leader when Marlon leaves.’ Barbara glanced at me in the rear-view mirror, ‘The whole team is tired, you’ll see.’

The car crossed over a long narrow bridge, and through the red metal railings I could see the waters of the River Sewa gushing over the large rocks below, crashing into small whirlpools. Crowds of people were vigorously washing their clothes and their bodies on the sloping shores. At the end of the bridge, the metal railings were torn open, twisted like a ribbon and dangling over the side, where a vehicle had hurtled through, dropping into the river below. Not hugely reassuring. We took a sharp left past a small village of resettled Liberian refugees, and continued down a straight mud road, past a primary healthcare centre, which MSF also supported, to the heavy metal gates of the Gondama Referral Centre. A sign was fixed next to the gate; in large painted letters, it declared this a place for serious problems in pregnancy and delivery.

I already knew one of the doctors working in GRC. I had met Alessandro back in March, when we spent a week together in Germany on a preparatory course for new MSF volunteers.* He was tall, lanky, the epitome of an extrovert, and he spoke in a thick Italian accent, his long arms moving in time with its rhythm, as if conducting his own orchestra. During the workshops on humanitarianism we had shared opinions. Over meals and drinks in the bar, we had continued the debates, which evolved into lengthy conversations stretching into all reaches of our lives. We confided our ambitions and our fears to each other, what we hoped to gain from our time with MSF and what we were afraid we’d miss out on at home while we were away. Alessandro had already been in Sierra Leone for three months, and when Severine had mentioned my name regarding the availability of an obstetric post, he had told her, ‘Take him’. Knowing he would be there among all the unfamiliar faces was some comfort to me.

Barbara had work to do, and I was keen to find the obstetrician, Crys, and see the maternity department for myself. Barbara called Crys on her mobile, but she was scrubbed in theatre for a caesarean section. Hearing this, a wave of anxiety rippled through me. I was actually here, and I really would be performing surgery in this place. Barbara gave me directions, but within a moment I was lost. GRC was made up of separate one-storey buildings and a street map of deep troughs, built to drain the heavy rainfall away. There was no obvious system or plan and I had no orientation as to where I was. I was a stranger in a strange land.

‘Is this the maternity?’ I asked a Sierra Leonean nurse standing at the entrance to one of the buildings.

‘You need to put scrubs on before you come in here,’ she said, dismissing me.

There was no moment of welcome. No formalities at all. This may have all been new to me, but for those working in the department I was just another expat who would come, stay a while and then leave, like the many others before me.

Once I had discovered where to find scrubs, I got changed into the oversized vestments. The large V of the scrub top reached down to my midriff. I yanked it back, hoping to appear less exposed. I put a mob hat and face mask on and cautiously stepped into the operating theatre. Standing on either side of the operating table was the surgeon and an assistant, both completely covered from head to toe, with just a small slit for their eyes, as if they were operating in synthetic burkas. I tiptoed over and let my presence in the theatre be known. Crys was stitching the uterus; I watched as she efficiently brought the two sides together. A knock came from the swinging door connecting the theatre to the delivery room, and a head popped around the side. A tall, broad Kenyan midwife shouted across the theatre, ‘Are you almost done? We need to do another.’

Crys shouted back over, ‘What’s the problem?’

‘Fetal heart rate is slow, not coming back up.’

‘OK, get her prepared.’

My heart pounded. There were so many questions rushing through my head. In all the literature and discussions before I came out to the field, the indications for a caesarean section were explained to be predominantly for the life of the mother. One fifteen-year-old girl out of every twenty-one in Sierra Leone, at that time, was estimated to die from childbirth complications during her lifetime. Many of the women would go on to have a high number of pregnancies. Performing a caesarean section was a decision to be taken judiciously. Leaving a permanent scar on the uterus would expose the woman to higher-risk pregnancies in the future and additional complications. Fetal distress was hard to judge when only using a handheld fetal heart rate monitor. If the diagnosis was correct, distress due to a lack of oxygen reaching the fetus’s brain, then you risked performing a caesarean for a baby with a poor chance of survival, in a place with limited resources for resuscitation or ongoing care. I understood the logic to this, even though it sat a world away from the type of obstetric care in labour I was used to, which was largely fetal-focused, with high rates of intervention and neonatal intensive care units. Working in a maternity ward back home was like being in a constant pressure cooker, the clock always ticking and there was huge stress to ensure interventions happened rapidly. If a midwife on a labour ward in the UK announced that a fetal heart rate was slow and not recovering, the alarms would be ringing. The crash call for emergency teams would have gone out. Within minutes, the woman would be on the operating table and the baby out. Here, this same diagnosis was met with routine normality, no rush. Get her prepared and put her in the queue.

The caesarean section over, Crys de-robed, revealing a confident and forthright person, with a trendy disposition. I could easily imagine her working in any large European or US city.

‘Let’s get a cup of tea,’ she said over her shoulder as she began heading out of the department. It was more like a command than a suggestion. I ran behind, my brain still trying to figure out what was going on. Wasn’t an emergency caesarean for fetal distress about to begin?

‘Nothing happens quickly here,’ Crys said, as if reading my thoughts. ‘You’ll get used to it.’ She turned back to the team. ‘Call me when she’s in.’

I didn’t know where to begin, I had so many questions about working in GRC. What was the daily routine? What were the local nurses and midwives like? Who could I trust and who should I not? Where were the notes written, and who should I call if there was a disaster? What about blood for transfusion? What about HIV? What about Lassa fever?

In the break room Crys made her tea, rearranged a fan so it blew directly on to her and then lay down on a couch. She was already experienced at working in this setting, having spent time in Afghanistan, Pakistan and other MSF projects. There was no messing around; we were straight down to business and she was giving me the proverbial coffee.