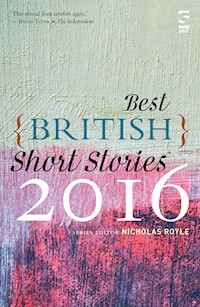

Best British Short Stories 2016 E-Book

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The nation's favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its sixth year. Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor's brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume. This new anthology includes stories by: Claire-Louise Bennett, Neil Campbell, Crista Ermiya, Stuart Evers, Trevor Fevin, David Gaffney, Janice Galloway, Jessie Greengrass, Kate Hendry, Thomas McMullan, Graham Mort, Ian Parkinson, Tony Peake, Alex Preston, Leone Ross, John Saul, Colette Sensier, Robert Sheppard, DJ Taylor, Greg Thorpe and Mark Valentine.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Best British Short Storiesinvites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor’s brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume.

This new anthology includes stories by: Claire-Louise Bennett, Neil Campbell, Crista Ermiya, Stuart Evers, Trevor Fevin, David Gaffney, Janice Galloway, Jessie Greengrass, Kate Hendry, Thomas McMullan, Graham Mort, Ian Parkinson, Tony Peake, Alex Preston, Leone Ross, John Saul, Colette Sensier, Robert Sheppard, DJ Taylor, Greg Thorpe and Mark Valentine.

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS EDITIONS

‘It’s so good that it’s hard to believe that there was no equivalent during the 17 years since Giles Gordon and David Hughes’s Best English Short Stories ceased publication in 1994. The first selection makes a very good beginning … Highly Recommended.’ —Kate Saunders,The Times

‘Another effective and well-rounded short story anthology from Salt – keep up the good work, we say!’ —Sarah-Clare Conlon,Bookmunch

‘Nicholas Lezard’s paperback choice: Hilary Mantel’s fantasia about the assassination of Margaret Thatcher leads this year’s collection of familiar and lesser known writers.’ —Nicholas Lezard,The Guardian

‘This annual feast satisfies again. Time and again, in Royle’s crafty editorial hands, closely observed normality yields (as Nikesh Shukla’s spear-fisher grasps) to the things we ‘cannot control’.’ —Boyd Tonkin,The Independent

Best British Short Stories 2016

NICHOLAS ROYLE is the author of more than 100 short stories, two novellas and seven novels, most recently First Novel (Vintage). His short story collection, Mortality (Serpent’s Tail), was shortlisted for the inaugural Edge Hill Prize. He has edited twenty anthologies of short stories, including A Book of Two Halves (Gollancz), The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories (Penguin), Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds (Two Ravens Press) and five previous volumes of Best British Short Stories (Salt). A senior lecturer in creative writing at the Manchester Writing School at MMU and head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, he also runs Nightjar Press, publishing original short stories as signed, limited-edition chapbooks. His latest publication is In Camera (Negative Press London), a collaborative project with artist David Gledhill.

Also by Nicholas Royle:

novels

Counterparts

Saxophone Dreams

The Matter of the Heart

The Director’s Cut

Antwerp

Regicide

First Novel

novellas

The Appetite

The Enigma of Departure

short stories

Mortality

In Camera(with David Gledhill)

anthologies(as editor)

Darklands

Darklands2

A Book of Two Halves

The Tiger Garden: A Book of Writers’ Dreams

The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories

The Ex Files: New Stories About Old Flames

The Agony & the Ecstasy: New Writing for the World Cup

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing

The Time Out Book of Paris Short Stories

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing Volume2

The Time Out Book of London Short Stories Volume2

Dreams Never End

’68: New Stories From Children of the Revolution

The Best British Short Stories 2011

Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds

The Best British Short Stories 2012

The Best British Short Stories 2013

The Best British Short Stories 2014

The Best British Short Stories 2015

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Introduction and selection copyright © Nicholas Royle,2016

Individual contributions copyright © the contributors,2016

The right ofNicholas Royleto be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2016

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-064-5 electronic

To the memory of novelist, short story writer and editor John Burke (1922–2011), whose landmark anthology,Tales of Unease(1966), is fifty this year.

Nicholas Royle

Introduction

As editor ofthis series I read as widely as possible – magazines, anthologies, collections, chapbooks, online publications – as well as trying to catch stories on BBC Radios 3 and 4, but it would be a full-time job to read every story, catch every broadcast. Each year I discover something new, invariably something that has been around for ages, likeBrittle Star. Issue 36 of this attractive little magazine contained powerful stories from Kate Venables, DA Prince and Stewart Foster, as well as the outstanding ‘My Husband Wants to Talk to Me Again’ by Kate Hendry. There was also an interesting non-fiction piece by Sarah Passingham about writers reading their work in public. Sarah Passingham had three stories published in 2014 in a highly desirable booklet,Hoad and Other Stories, by Stonewood Press, who are also responsible forBrittle Star. A copy was sent toBest British Short Stories, but, through no fault of Stonewood’s, didn’t reach me until it was too late to be considered for the 2015 volume. This is frustrating because at least one of those three stories, probably ‘Hoad’, would definitely have made it into the final line-up.

Another small publisher, Soul Bay Press, sent me a collection of stories by Samantha Herron, The Djinn in the Skull: Stories From Hidden Morocco. The author spent time in a community on the edge of the Sahara collecting the tales of storytellers and writing her own stories. Part of the appeal of her collection lies in trying to work out which pieces are traditional tales and which might be the product of Herron’s imagination. Other notable collections that landed on my desk included: excellent debuts from Claire-Louise Bennett (Pond, Fitzcarraldo Editions) and Crista Ermiya (The Weather in Kansas, Red Squirrel Press); Quin Again and Other Stories (Jetstone) by the ever-acute Ellis Sharp; another debut, Jessie Greengrass’s An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, According to One Who Saw It published by JM Originals, where editor Mark Richards is spotting some excellent writers and producing beautiful books; Hermaion: Happy Accident, Lucky Find (Hermaion Press) by Amanda Schiff with photographs by Jane Wildgoose; Joel Lane’s The Anniversary of Never posthumously published in a very handsome edition by the Swan River Press; second collections from DJ Taylor (Wrote For Luck, Galley Beggar Press), HP Tinker (The Girl Who Ate New York, East London Press) and Graham Mort (Terroir, Seren); Marina Warner’s third collection, Fly Away Home (Salt), and Janice Galloway’s fourth, Jellyfish, which was her first with Freight Books, who also published Pippa Goldschmidt’s The Need For Better Regulation of Outer Space.

I have been waiting years – yes, years – for Stuart Evers’ story, ‘Live From the Palladium’, to appear in print, after I heard him read it at a Word Factory event. It was finally published last year, in his second collection, Your Father Sends His Love (Picador). There’s one other story in this book that I first encountered when I heard it being read by its author (at the Hurst, in Shropshire, when Leone Ross and I were sharing tutor duties on an Arvon week) and that’s ‘The Woman Who Lived in a Restaurant’, which I fell in love with on first hearing and persuaded Ross to let me publish as a chapbook through Nightjar Press.

The terms ‘collection’ and ‘anthology’ are regarded by some people as interchangeable. Well, if you want to live in a chaotic universe with no fixed points, nothing to hold on to, you go ahead, but for me a collection will always be a single-author collection while an anthology will contain stories by various authors and there will be an editor, or editors, credited. The distinction between an anthology and a magazine, however, is not always clear.Gutteris a beautifully produced 186-page book – there’s no other word for it – edited by Colin Begg and Adrian Searle and published twice-yearly by Freight Books (see?) and containing short stories, poetry and reviews, but its tag line states unambiguously, ‘The magazine of new Scottish writing.’Gorseis another one. Published twice a year in Dublin and edited by Susan Tomaselli,Gorselooks like a book, with a lovely design aesthetic and highly tactile soft matt cover, but self-identifies as a journal ‘interested in the potential of literature, in literature where lines between fiction, memoir and history blur’. Issue 4 containedThe Beginning of the Endauthor Ian Parkinson’s first published short story.The Mechanics’ Institute Review, on the other hand, published annually by the MA Creative Writing at Birkbeck, is described by project director Julia Bell in the introduction to issue 12 as a ‘curated collection’.

#1ShortStoryAnthology appears straightforward until we read in series editor Richard Skinner’s introduction, ‘What you are holding in your hands is the second in our series of anthologies made up of work by people who have read at Vanguard Readings, a monthly series of readings that take place in The Bear pub in Camberwell, south-east London.’ The second? #1? Soon all becomes clear, however. The first anthology was entitled #1PoetryAnthology. Their first short story volume, guest-edited by Adrian Cross and Des Mohan, includes some excellent stories by Alex Catherwood, Stuart Evers and Jonathan Gibbs, whose ‘Southampton’ would have been in the present volume if I could have squeezed in just one more story.

Turning briefly to the world of self- or collective publishing, firstly, Revolutions is edited by Craig Pay, Graeme Shimmin and Eric Steele and published by Manchester Speculative Fiction Group. It includes new work by members of the group and writers not normally associated with speculative fiction. Secondly, Congregation of Innocents is the third Curious Tales anthology, featuring new stories by Emma Jane Unsworth, Richard Hirst, Jenn Ashworth and Tom Fletcher and an introduction by Patrick McGrath (whose collection Blood and Water was published in the ground-breaking Penguin Originals list in 1989) highlighting the anthology’s stated intention to pay tribute to Shirley Jackson who died half a century ago last year.

There were some outstanding stories in Flamingo Land and Other Stories (Flight Press) edited by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, particularly those by Colette Sensier, Uschi Gatward and Shaun Levin. Flight Press is an imprint of Spread the Word, whose Flight 1000 programme helps ‘talented people from under-represented backgrounds gain experience, contacts and routes into the [publishing] industry’.

The Fiction Desk continues to be active, publishing three anthologies a year. Volume nine, Long Grey Beard and Glittering Eye edited by Rob Redman, featured good work by Mark Newman and Richard Smyth among others. The Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology Volume 8 (no editor credited, but the prize was judged by Sara Davies, Rowan Lawton, Sanjida O’Connell and Nikesh Shukla) was packed with good stories; I especially enjoyed Mark Illis’s ‘Airtight’.

Possibly my favourite anthology of 2015 was Transactions of Desire (HOME Publications) edited by Omar Kholeif and Sarah Perks and published to coincide with an exhibition, The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things, at HOME. It’s a bit hit and miss in some respects – inconsistent layout; failure to acknowledge earlier appearance of at least one story; and my copy is already falling apart – but when the work is as good as some of the stories on show here, the overly critical pedant in you relaxes, just a little. A number of stories stood out, in particular those by Emma Jane Unsworth, Adam O’Riordan, Jason Wood, Katie Popperwell and Greg Thorpe, whose ‘1961’ takes place against the backdrop of what has been called ‘the greatest night in showbusiness history’, the night Judy Garland played Carnegie Hall on 23 April 1961.

Indubitably a magazine and not an anthology,London Magazinereached out and responded to one of my overly critical tweets – about how they’d previously refused to send me review copies – by saying they’d be happy to send me one after all. The August/September issue duly arrived, containing only two stories and one of them was by the magazine’s editor, Steven O’Brien, which made me not only smile but actually laugh out loud, for it was O’Brien including his own work in the magazine that had prompted the remarks I made three years ago when I wrote aboutLondon Magazinein the introduction toBest British Short Stories 2013. We’ve all seen the endless photographs online (haven’t we? I’m surely not alone in spending my evenings poring over them) ofLondon Magazine’s glittering champagne receptions. Is there no one among those lords and ladies able to advise O’Brien on etiquette? What about special editorial adviser Grey Gowrie? Oh no, his work has appeared in the magazine on a number of occasions as well. All right then, literary consultant Derwent May? Nope, he too is a contributor.

Maybe the issue is not so much one of etiquette, but of cool versus uncool. It just doesn’t seem cool to regularly publish your own stories and poems in a magazine of which you are the editor (unless you hide mischievously behind a pseudonym, of course). In recent years, while London Magazine and Ambit have been the two best-known London-based literary magazines, it’s been fairly obvious which one is James Ellroy, if you will, and which RJ Ellory. When it launched in 1959 under the editorship of Dr Martin Bax, Ambit was cool. Fifty-odd years later it’s still cool. Highlights during 2015 included stories by Jonny Keyworth, James Clarke, Louise Kennedy, Giselle Leeb and Alex Preston. Ambit is now edited by Briony Bax, the fiction edited by Kate Pemberton assisted by Gwendolen MacKeith, Mike Smith and Gary Budden, who contributed a piece of interesting non-fiction to issue 13 of another good magazine, Structo, which, in its next issue, 14, published an entertaining story by Jonathan Pinnock and an interview with David Gaffney, who appeared with an excellent story in Confingo 4, the previous issue of that magazine having featured very enjoyable stories by Stuart Snelson, John Saul and Charles Wilkinson.

Prospect now appears to have banished short fiction to twice-yearly supplements. The Winter Fiction Special featured a Don DeLillo story that hadn’t been original even to the anthology it was extracted from, Ben Marcus’s New American Stories (Granta Books), but the Summer Fiction Special, more happily, had featured an original and substantial story by Tessa Hadley. The Guardian also published an Original Fiction Special in the summer, with new stories by Tessa Hadley, again, and Will Self among others. Over the course of 2015, the New Statesman published new stories by Jeanette Winterson and Ian Rankin and two stories by Ali Smith.

Danish magazine Anglo Files, produced for teachers of English in Denmark, continues to publish English-language short stories. In issue 177 they featured Tony Peake’s touching ‘The Bluebell Wood’. At least one new print magazine devoted to short stories started up in 2015, namely Shooter (search for Shooter literary magazine to find it online). I saw two other magazines for the first time last year: issue 30 of Supernatural Tales, edited by David Longhorn, which included Mark Valentine’s ‘Vain Shadows Flee’, a tribute to the late Joel Lane, who would have loved it, and Melbourne-based The Lifted Brow, featuring a story by Chris Vaughan, ‘To Crawl into Glass’, that made the shortlist for the present volume.

The magazine I most look forward to receiving (four times a year) is Lighthouse, which lists no fewer than ten editors, among them Philip Langeskov, whose work has been included in this series more than once. I could almost fill this book with stories from Lighthouse. On this occasion I have restricted myself to one, by Thomas McMullan, but could easily have gone for stories by Gareth Watkins, Ruby Cowling and Lander Hawes. And, finally, a quick word regarding The White Review. I don’t quite know why I haven’t taken anything yet from this gorgeous-looking magazine. The story of theirs that I liked best this year was published online, in May 2015. ‘Gandalf Goes West’ by Chris Power is the story Beckett might have written had he ever got into video games.

For up-to-date lists of literary magazines and online publications (three of the stories in this book were first published online – John Saul’s in The Stockholm Review, Trevor Fevin’s in St Sebastian Review and Neil Campbell’s in The Ofi Press Magazine), keep a close eye on ShortStops and Thresholds web sites. Both are excellent resources.

Robert Sheppard’s ‘Arrivals’ is the first story I’ve taken from a work of, predominantly, autobiography, butWords Out of Time(Knives Forks and Spoons Press) is no ordinary attempt at life writing, subtitled as it is ‘autrebiographies and unwritings’. I was just sitting here reflecting that the line I quoted above from theGorseweb site – ‘interested in the potential of literature, in literature where lines between fiction, memoir and history blur’ – would not have been at all out of place on the cover ofWords Out of Timewhen I opened that book at random for another flick through and my eye fell directly on this line in a piece entitled ‘With’: ‘The Downs with dark gorse clinging to its sides.’ You couldn’t make it up. Or, more to the point, you wouldn’t bother making it up.

Novelist, short story writer and editor Tony White’s story, ‘High-Lands’, appeared in print for the first time in 2015, in Remote Performances in Nature and Architecture (Ashgate) edited by Bruce Gilchrist, Jo Joelson and Tracey Warr, having been broadcast on the radio and available as a download since 2014. White also runs Piece of Paper Press, which he started in 1994 as a ‘lo-tech, sustainable artists’ book project used to commission and publish new writings, visual and graphic works by artists and writers’. Each release is in the form of a single piece of A4 printed on both sides, then folded, stapled and trimmed. Copies are numbered and are always given away free. In 2015 Piece of Paper Press published a story by Joanna Walsh, ‘Shklovsky’s Zoo’, which I wanted to reprint in this book, but Walsh declined, preferring that the story should remain unavailable once copies had been distributed. She said: ‘I like that the work should necessarily have a kind of sillage to it (autocorrected to “silage”: that’ll teach me to be pretentious!) that occurs around its non-availability.’ Which reminds me of US author Shelley Jackson’s story ‘Skin’, published on the bodies of 2095 volunteers (one word per volunteer, which they undertook to have tattooed somewhere about their person) and made available to read exclusively to those volunteers, who were henceforth known as ‘Words’ and who were bound to agree not to share the story with any non-Words, which is a shame because it’s a beautifully written and powerful story.

Final word this year goes to Dennis Hayward, known simply as Dennis at Fallowfield Sainsbury’s in Manchester, where he works on the tills. Every year Dennis writes a Christmas story, copies of which he sells to customers and staff, the proceeds going to a local charity. Last year’s story, ‘The Christmas Party’, raised £1365 for Francis House Children’s Hospice. I don’t want to wish the summer away before it’s even arrived, but I am looking forward to buying my own copy of this year’s story, which Dennis tells me is already written and ready to go.

Nicholas Royle

Manchester

April 2016

Leone Ross

The Woman Who Lived in a Restaurant

One high dayin February, a woman walks into a two-tier restaurant on a corner of her busy neighbourhood, sits down at the worst table – the one with the blind spot, a few feet too close to the kitchen’s swinging door – and stays there.

She stays there forever.

She wears a crisp cotton white shirt with a good collar and cuffs and a soft black skirt that can be hiked up easy. She has careful dreadlocks strung with silver beads – the best hairstyle to take into forever. There is no more jewellery: her skin is naked and moist. She keeps a tiny pair of white socks in her handbag, and in the cold months, she slips them onto her bare feet.

She watches the waiters, puppeting to and fro, the muscles in their asses tightening and relaxing, thumbing coin and paper tips, tumbling up and down the stairs and past her to the kitchen, careful not to touch. The maître d’ has a big belly and so does the chef, who is also the owner of the restaurant. Nobody holds it against them; this is not fat, it is gravitas, and also they work very long hours and eat much of the chef’s extremely fine food. – Smile, smile, the maître d’ says to everybody, staff and customers alike; he has been here for the longest and she never hears him say much more in front of house, although you would have thought he might.

She goes to the restroom in the mornings and evenings, to wash her skin and to put elegant slivers of fresh, oatmeal soap to her throat and armpits. She nods at the diners, who bring children and lovers and have arguments and complain and compliment the food and some that get drunk and then there’s the sound of vomiting from the bathroom that makes her wince. So many propose marriage, eventually she can spot them on sight: the men lick their lips and brandish their moustaches and crunch their balls in their hands. They all flourish the ring in the same way, like waiters setting down the pièce de résistance: fresh steak tartar or gyrated sugar confectionaries that attract the light. Their women – provided they are pleased – do identical neck rolls and shoulder raises and matching squeals, like a set of jewellery she thinks, all shining in their eyes, although one year a woman became very angry and crushed her good glass into the table top.

– I told you not to kill it with this lovey-dovey shit! she yelled at the moustachioed man, and stalked out. The man sat with the napkin under his chin, making a soft, white beard. The napkins here are of very good quality.

– Hush, said the restaurant woman, like she was rocking the small pieces of the leftover man. The people around them ate on and tried to ignore the embarrassed, shattered glass.

– What shall I do? he asked, rubbing his mouth with the napkin.

– Love is what it is. She stretched one finger skyward, as if offering an architectural suggestion.

He hurried out and away, his shoes making scuffling noises like mice.

These days she must rock from cheek to cheek to prevent sores. But mostly she sits and waits and smiles to herself and her lips remind the male waiters of the entrails of a plum, so juicy and broken open. They see that she is not young, although she has good breasts and healthy breath. Watch how she taps her fingers on the table and handles the glass stem, they whisper: this is a woman of authority. She has been somebody. Some of the waitresses weep but most of them hiss that she is a fool.

– Mind the chef kill you, the line cook whispers.

One waitress deliberately spills fragrant, scalding Jamaican coffee onto the woman’s wrist. The woman rubs her burned flesh and smiles. The waitress shudders at her happy brown eyes. – Stupid bitch, the waitress hisses. – Why are you here?

She is fired the next day, as are all waitresses who hate the woman.

A young, male waiter fills the vacancy, three years and thirteen hours after the woman arrives to live in the restaurant. She sees him come in for the interview: nervous with his thick, curly hair and handsome bow legs.

On his first day, the waiter comes running to the pass to say that he has seen a woman bathing in the restroom sink, and that her body was long and honeyed and gleaming in the early light through the back window. He didn’t mean to see her, really, he says. He was dying for a piss and opened the wrong door.

What he does not say is this. That when he opened the door, the woman was sitting naked, with her shoulder blades propped up against the beam between the cubicles. Her legs were spread so far apart that the muscles inside her thighs were jumping. She had the prettiest pussy he’s ever seen, so perpendicular and soft that he had to shade his eyes and take a breath, and then, without knowing he was capable of such a thing, he stopped and stared.

– Put simply, he says to his closest friend, that night, while drinking good beer and wine, she was too far gone to stop.

They sigh, together.

The woman, who had been rolling her nipples with the fingers of both hands before he came in, put a hand between her legs. At first he thought she was covering herself, but then he saw the expression on her face and realised that this was a lust he’d never seen before. The woman took her second and third fingers and rubbed between her legs so fast and hard that the waiter, who thought he’d seen a woman orgasm before this, suddenly doubted himself and kept watching to make sure. In the dawn, the woman’s locks could have been on fire and even the shining tiles on the bathroom floor seemed to ululate to help her.

– Ah, said the woman. – Oh.

The smallest sound, so quiet. It was like a mouthful of truffle or a perfect pomegranate seed on the tongue: an unmistakeable quality.

Weeks pass, and the new waiter is miserable, not least because he knows now that he has never made a woman orgasm.

– What is she doing here, hardly ever moving from her seat? Does she not have a home?

– Mind the chef kill you, they whisper around him.

Despite their warnings he rages on, making the soup too peppery and the napkins rough.

Finally, the maître d’ tells him the story, in between cold glasses of water, changing tarnished forks, and cutting children’s potato cakes into four pieces each. All through it, the waiter tries not to look at the woman under his eyelashes, although when he does, she still glows and when the chef sends her an edible flower salad for her luncheon, he can smell the salt on her second and third fingers when he puts it down in front of her.

The maître d’ explains that the story is in the menus, if you read them closely enough.

The chef is that kind of man who is in love with his work. He has owned the restaurant for twenty-two years and it is everything. He creates ever more beautiful and tasty dishes; he admires the beams and wall fixtures and runs loving fingers over the icy water jugs and bunches of fresh beans in the kitchen. The mushrooms are cleaned with a specially crafted brush. Hours must be spent in the streets talking with butchers and fishermen so that the restaurant has the freshest, most rare ingredients. Each tile in the floor has been hand-painted. Each window-sash hand-made. He has been known to stroke the carpet on the stairs, and he knows the name and taste buds of every regular customer.

He is a happy and most successful man.

But then he meets the gleaming, honeyed woman in a farmers’ market. She is buying a creamy goat’s cheese and several wild mangoes, and he will not ever be quite able to say why, but he stops and talks and points out the various colours of the dawning sun above the market, and the gathering day draws purple shadows over the woman, like bruises, and he likes her very much indeed. He thinks there is something missing from his life, and that he wants something from her.

At first the chef did not worry, says the maître d’ to the young waiter. He knew that he could love, because he loved the restaurant and while some might say one cannot love a restaurant the way one loves a woman, both take time and attention, so there we are.

– There we are, where? snaps the waiter. – We are not anywhere. Why is that woman sitting there for years?

– You understand nothing, says the maître d’. – You should wait for the rest of the story.

The chef, says the maître d, prepared for change. He would do so-and-so at a different time, so he would be able to kiss the woman. And this ingredient, well, he would not be able to rise quite so early to collect it, and would have to make do with another version, for after he and the woman were lovers, he would not want to rise quite as early in the morning. And so on. The chef brought the woman to see the restaurant and she sat on its couches and chairs, and admired its warm stove and brightly coloured walls. She brought several good and mildly expensive paintings, as obeisance, and very good flowers, bird of paradise and swamp hibiscus, walking around both tiers, lovingly arranging them in bowls. But even then, it seemed, she knew something. She stayed out of the kitchen when the chef was busy, even when he smiled and called her in. – The steam will play havoc with my hair, darling, she said, for these were the days that she hot-comb straightened it.

– We all knew it was coming, of course, says the maître d’, signalling for the boys to peel the potatoes louder and to bang the pots, so that the chef cannot hear his gossiping. – We all knew, for after all, which sensible man introduces his girlfriend to his wife?

Three months after meeting, the sweethearts decided to consummate their affair. On that fated night of intention, the woman arrived for dinner and stayed until 1am, which was as early as the chef would close. The staff waited to be dismissed, glad for a break and glad for the lovers. The chef tried to stop looking like a cat with several litres of fresh cream – and tried to stop sweating. The woman, ah, so sweet she was: nervous and happy. They were transformed in their anticipation of the lovemaking: like young things, and neither of them young.

They were leaving through the front door when the restaurant moved two inches to the right.

That’s correct, we all felt it, standing there, says the maître d’. It was hard to explain, even today, and the architect who came to see the torn window frames and the shattered tiles said it was an earthquake, albeit a very contained and small one. Electrics twisted, stove mashed, water from burst pipes running down the coral dining room walls. They opened the crooked fridges and out belched rotted fowl and fauna, blackened, sweet with ruin, filling the air, making them all choke. So much money lost! – Smile, smile, I told them all, but the sound! The plumbers said it was the pipes and the electrician, she said it was the wiring, but no one knew, except all of us.

The restaurant would not be left on its own, so it was crying.

– Will you not kiss me, said the woman, tugging at the chef, but no, he was unable.

– We could go far away from here, she begged, but he looked at her as if she was mad.

– I would not hurt her, he said, almost stern.

– A restaurant? she said, and she tried to fit all the pain of that into those two words.

It is a good restaurant, he said. And turned back to work.

The newly hired waiter interrupted. He was almost stuttering in his outrage.

– So-so-so—?

The maître d’ pulled a pig haunch close to him and began to burn the bristles on the hot stove. It was not his job, but he liked doing it.

– So, the woman came to live here. She stays here so that she can see the chef, and the restaurant keeps watch.

– But-but—

The maître d’ smiled, almost sadly, tossing the hot pig from palm to palm. –They sit together, between service, and talk. They do not touch. He shrugged towards the restroom. –We have seen her too, my friend. It must be terribly frustrating.

The woman becomes aware that something has changed. Truly, she has seen staff appalled before this. Seen them lounging around her, trying to get her attention. But this young waiter seems more determined, in that way of youth, and he keeps touching her.

– Will you not come to the front door with me? he says, over her porridge breakfast, sent out strictly at 9.31am. – There are pink blooms all over the front of the restaurant, and ivy, and it is so very good.

– You can describe it for me, she says, smiling and ripping her languid eyes away. There is lavender, sprinkled in an intricate pattern, on top of her porridge.

The next day: come for a walk with me upstairs, he says. To the balcony. It will be good for you to have the air. The chef – she moves her shoulders in delight at the sound of his name and slices into the waiter’s heart – the chef, he has gone out to buy vegetables.

– I know, she says. – He tells me everything that he does. But I’ll stay here. It will be better.

– Better than what?

She laughs, shifts, pats his shoulder. – Better than missing his return, she says, as if he is a stupid child. She gestures to the front door, which is clear because it is too early for the madness of diners. – I will see him with the sun against his back, and he assures me that from that distance, he can see the purple shadows on me. It will give us much pleasure.

One afternoon, the waiter can control himself no longer, and pulls the woman to her feet, feeling her burning skin beneath his fingers. He is surprised to find the chef suddenly there, standing between them, belly glaring, his best knife tucked behind him. The waiter need say nothing more; his job, perhaps his life, is in jeopardy.

But still, he thinks of her. At night, he pulls himself raw. He thinks of her over and above him, and in time the fantasies become vile and violent things; in his desperation he can think of nothing but defiling her, mashing her lips against the wall of his bedroom. He becomes a whisperer, appals himself by hissing at her, like others before him. At first she cannot hear him when he mutters under his breath. – Stupid bitch, he says. – Stupid fucking bitch. But soon he cares less and says it when he passes her sweeping, and as he puts filo pastry, with fresh bananas, passion fruit sauce and black pepper ice cream in front of her. – Stupid bitch, I hope it makes you fat and ugly. She looks away, smiling into the distance.

A diner complains.

– Each time I come here, that woman is served something exquisite, off menu. Last week it was out-of-season cherries with kirsch. Last month it was avocado rolls. Why does the chef show such favouritism?

The young waiter rushes over. – Madame, that is because she is a stupid bitch, and he is a cruel bastard.

– Oh my, says the disgruntled diner.

That evening, the waiter is fired. Before he leaves, he pisses in the fish stew on the stove, throws out a batch of very expensive hybrid vodka and flashes his cock at the calm and waiting woman sitting at the table, circling her wrists and pointing her pretty toes under the tablecloth. Her backbone makes a crackling noise.

– What are you waiting for? he screams at her, as sous chef and maître d’ wrestle him out. – What are you waiting for him to give you?

She answers him, but there is a noise in the walls of the restaurant and so he cannot hear what she says.

In the lateness of the night, she rises from the table. After these many years, she has become attuned to the restaurant, and to her beloved. They work in tandem. She can hear the eaves sigh in the wind, feel the dining room chairs sag with relief as the frenetic energy of the day finally draws to a close.

She pushes open the door to the kitchens and steps in, light.

The chef is slumped over a stained steel surface, tired, a good wine at his head. He looks up and smiles at her. It is the best part of his day. The love of the restaurant around him, and now, this sweet woman. She leans on the work surface and faces him, smiling back.

He remembers her complaining, wailing friends. One tried to get the restaurant shut down. Another threatened arson. Her brother, he was the worst. He came to his home, and begged.

– If she does this, my friend, she will give up everything. Home. Job. The chance of children. And worst of all, she will be second best. You make her second best.

– I know, he said. But she is stubborn.

He has learned to live with guilt. Some days, he thinks it is harder for him. So many of the staff become angry, especially the women. To love them both is tiring. But he has come to respect the woman’s choice.

He groans, content, as she steps behind him, puts her arms around him, nestles into the sensitive skin at his neck.

– Hello, my love, she says. He reaches behind him, hooks his hands at the small of her back. They look up, towards the ceiling, as if making architectural decisions.

– Has anything changed? she asks, like she has every night, for years.

They listen to the restaurant, creaking and warm.

– No, he sighs.

– Ah then, she says. Perhaps, tomorrow.

They kiss.