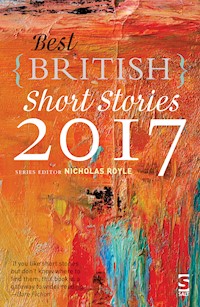

Best British Short Stories 2017 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Best British Short Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

The nation's favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its seventh year. Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This critically acclaimed series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor's brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume. Featuring stories by Jay Barnett, Peter Bradshaw, Rosalind Brown, Krishan Coupland, Claire Dean, Niven Govinden, Françoise Harvey, Andrew Michael Hurley, Daisy Johnson, James Kelman, Giselle Leeb, Courttia Newland, Vesna Main, Eliot North, Irenosen Okojie, Laura Pocock, David Rose, Deirdre Shanahan, Sophie Wellstood and Lara Williams.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 294

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BEST BRITISH SHORT STORIES 2017

The nation’s favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its seventh year.

Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This critically acclaimed series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor’s brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume.

Featuring stories by Jay Barnett, Peter Bradshaw, Rosalind Brown, Krishan Coupland, Claire Dean, Niven Govinden, Françoise Harvey, Andrew Michael Hurley, Daisy Johnson, James Kelman, Giselle Leeb, Courttia Newland, Vesna Main, Eliot North, Irenosen Okojie, Laura Pocock, David Rose, Deirdre Shanahan, Sophie Wellstood and Lara Williams.

PRAISE FOR BEST BRITISH SHORT STORIES

‘This annual feast satisfies again. Time and again, in Royle’s crafty editorial hands, closely observed normality yields (as Nikesh Shukla’s spear-fisher grasps) to the things we ‘cannot control’.’ —Boyd Tonkin, The Independent

‘Nicholas Lezard’s paperback choice: Hilary Mantel’s fantasia about the assassination of Margaret Thatcher leads this year’s collection of familiar and lesser known writers.’ —Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian

‘Another effective and well-rounded short story anthology from Salt – keep up the good work, we say!’ —Sarah-Clare Conlon, Bookmunch

‘It’s so good that it’s hard to believe that there was no equivalent during the 17 years since Giles Gordon and David Hughes’s Best English Short Stories ceased publication in 1994. The first selection makes a very good beginning … Highly Recommended.’ —Kate Saunders, The Times

‘When an anthology limits itself to a particular vintage, you hope it’s a good year. The Best British Short Stories 2014 from Salt Publishing presupposes a fierce selection process. Nicholas Royle is the author of more than 100 short stories himself, the editor of sixteen anthologies and the head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, which inspires a sense of confidence in his choices. He has whittled down this year’s crop to 20 pieces, which should enable everyone to find a favourite. Furthermore, his introduction points us towards magazines and small publishers producing the collections from which these pieces are chosen. If you like short stories but don’t know where to find them, this book is a gateway to wider reading.’ —Lucy Jeynes, Bare Fiction

Best British Short Stories 2017

NICHOLAS ROYLE is the author of more than 150 short stories, two novellas and seven novels, most recently First Novel (Vintage). His first short story collection, Mortality (Serpent’s Tail), was shortlisted for the inaugural Edge Hill Prize; his second, Ornithology (Confingo Publishing), was published in spring 2017. He has edited twenty anthologies of short stories, includingsix earlier volumes of Best British Short Stories. A senior lecturer in creative writing at the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University and head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, he also runs Nightjar Press, publishing original short stories as signed, limited-edition chapbooks.

Also by Nicholas Royle:

novels

Counterparts

Saxophone Dreams

The Matter of the Heart

The Director’s Cut

Antwerp

Regicide

First Novel

novellas

The Appetite

The Enigma of Departure

short stories

Mortality

In Camera (with David Gledhill)

Ornithology

anthologies (as editor)

Darklands

Darklands 2

A Book of Two Halves

The Tiger Garden: A Book of Writers’ Dreams

The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories

The Ex Files: New Stories About Old Flames

The Agony & the Ecstasy: New Writing for the World Cup

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing

The Time Out Book of Paris Short Stories

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing Volume 2

The Time Out Book of London Short Stories Volume 2

Dreams Never End

’68: New Stories From Children of the Revolution

The Best British Short Stories 2011

Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds

The Best British Short Stories 2012

The Best British Short Stories 2013

The Best British Short Stories 2014

Best British Short Stories 2015

Best British Short Stories 2016

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

International House, 24 Holborn Viaduct, London EC1A 2BN United Kingdom

All rights reserved

Introduction and selection copyright © Nicholas Royle, 2017 Individual contributions copyright © the contributors, 2017

The right of Nicholas Royle to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2017

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-113-0 electronic

To the memory of Alex Hamilton 1930–2016

Introduction

Nicholas Royle

One of my online students, meeting me recently for the first time, told me I am much less cantankerous in person than I am online. Or in print, she could perhaps have added. Since the appearance of the 2016 volume in this series I have been publicly ridiculed by the target of a poison-tipped arrow I launched in last year’s introduction. Steven O’Brien, editor of the London Magazine, attacked me where it hurts, i.e. online – where everyone can read it – having reacted to my criticising him for publishing his own work in the publication he edits. He didn’t mention this fact in his witty takedown, which made me wonder if he did feel a little embarrassed, after all. But why should he, I’m now thinking? He’s only showing that he’s imbibed the zeitgeist, that he’s part of the selfie generation.

He’s certainly far from alone. Of the fourteen anthologies published last year that are still sitting on my desk as I write this introduction, five feature stories by their editors. Those five range from the smallest, most modest publication, put together to benefit a refugee charity, to probably the biggest, most prestigious anthology of 2016, whose editors, strangely, are not credited until we get to the title page. But then, it should perhaps be noted, there is a tendency for stories by editors, in the small sample under review, to be among the longer stories in the book in each case.

There’s no getting away from the fact that 2016 was a terrible year, not only for Britain and Europe, but also America and the entire world. If we can forget Brexit and Trump for a moment, however, 2016 was a good year for the short story. Even as I make such a claim, in the light of the enormity of contextual events, it seems ridiculous to do so. In 2017, perhaps, short story writers will respond to the electoral upheavals of the previous year. Maybe they will be invited to respond, if anyone is putting together a Brexit anthology (horrible thought) or a Trump book (ugh). The themed anthologies of 2016 required contributors to seek inspiration from undelivered or missing post (Dead Letters edited by Conrad Williams for Titan Books), to commune with the spirit of either Cervantes or Shakespeare (Lunatics, Lovers and Poets edited by Daniel Hahn and Margarita Valencia for And Other Stories), to ponder the nature of finality (The End: Fifteen Endings to Fifteen Paintings edited by Ashley Stokes for Unthank Books), to imagine oneself an untrustworthy reporter on the capital (An Unreliable Guide to London edited by Kit Caless, assisted by Gary Budden, for Influx Press) or to get to grips with the big subjects of any and every year (Sex & Death edited by Sarah Hall and Peter Hobbs for Faber & Faber). In addition to the stories from these anthologies that are included in the present volume, I particularly enjoyed Deborah Levy’s ‘The Glass Woman’ and Rhidian Brook’s ‘The Anthology Massacre’ in Lunatics, Lovers and Poets and ‘Staples Corner (and How We Can Know It)’ by Gary Budden and M John Harrison’s ‘Babies From Sand’ in An Unreliable Guide to London.

Unthemed anthologies kept coming, from both within genre literature (Ghost Highways edited by Trevor Denyer) and without (The Mechanics’ Institute Review 13, Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology 9, The Open Pen Anthology). There were some particularly good stories in Dark in the Day edited by Storm Constantine and Paul Houghton (Siân Davies’s ‘Post Partum’ nicely echoing ‘Postpartum’ by Louise Ihringer in Ambit 226), Separations: New Short Stories From the Fiction Desk edited by Rob Redman (David Frankel’s ‘Stay’, especially) and Unthology 8 edited by Ashley Stokes and Robin Jones (I loved Amanda Mason’s ‘The Best Part of the Day’). In an unusual project, Something Remains (The Alchemy Press) edited by Peter Coleborn and Pauline E Dungate, writer friends, acquaintances and admirers of the late Joel Lane were invited to take an idea or opening from Joel’s notebooks and write their own story based thereupon. A lot of love, affection and homage – and good writing – is packed into the book’s 400 pages; it was published in aid of Diabetes UK.

Good stories by David Gaffney (‘The Man Who Didn’t Know What to Do With His Hands’) and Jason Gould (‘Not the ’60s Anymore’) were the highlights of two chapbook-sized anthologies publishing competition winners from the PowWow Festival of Writing (Stories edited by Charlie Hill) and the Dead Pretty City short story competition (Bloody Hull, stories selected and with a foreword by David Mark). Charlie Hill also popped up with Stuff (Liquorice Fish Books), an engrossing piece that was either a long short story or a short novella and that, were the author French and his readers all French, might well have been regarded as a worthy late addition to the school of existentialist literature. Jack Robinson’s beautifully written By the Same Author (CB editions) was in a seimilar vein, Robinson being a pseudonym used by Charles Boyle, who runs CB editions, but you never hear anyone giving him a hard time for publishing his own work.

There were fine stories in new collections from, among others, Penelope Lively (The Purple Swamp Hen & Other Stories), Lara Williams (Treats), Jo Mazelis (Ritual, 1969), Daisy Johnson (Fen), DP Watt (Almost Insentient, Almost Divine) and Michael Stewart (Mr Jolly). Charles Wilkinson’s A Twist in the Eye (Egaeus Press) was beautifully packaged with cover art and end papers reproducing infernal visions by a follower of Hieronymous Bosch. Claire Dean’s long-awaited debut collection, The Museum of Shadows and Reflections (Unsettling Wonder), came with hard covers and lovely illustrations by Laura Rae. The title story was one of many stories I read last year, in addition to the twenty selected, that I wish there was room for in the present volume. Anna Metcalfe’s debut, Blind Water Pass and Other Stories (JM Originals), demonstrated her publisher Mark Richards’ ongoing commitment to supporting excellent new short story writers.

Talking of which, the taste and editorial eye of Gorse editor Susan Tomaselli is one of the reasons why we could conceivably double the size of Best British Short Stories without any drop in quality. I wish I had room for stories by Will Ashon, Maria Fusco, David Rose and Bridget Penney from last year’s two issues of the oustanding Irish journal. I don’t know why I’m only just catching on to John Lavin’s The Lonely Crowd ‘magazine’ (it’s the size, format and heft of an anthology). I imagine the title character from Charlie Hill’s ‘Janet Norbury’, a librarian, in the Spring issue, would have made sure to stock books by the title character of Bridget Penney’s ‘Hugh Lomax’, a forgotten novelist, from Gorse 6. Neil Campbell’s ‘The Sparkle of the River Through the Trees’ was another stand-out among The Lonely Crowd.

It remains to be seen how the surprise departure of Adrian Searle from Freight Books will affect Gutter, the magazine of new Scottish writing, of which he was co-editor. No sign of any further personnel changes at Ambit, which published notable stories by David Hartley (‘Shooting an Elephant’ shared some common ground with Jenny Booth’s ‘I Know Who I Was When I Got Up This Morning’ in Brittle Star 39), Daniel Jeffreys, Adam Phillipson, Chris Vaughan and Fred Johnston. I always like Emma Cleary’s stories; her ‘Whaletown’ in Shooter 3, the ‘Surreal’ issue, was a highlight with its tumbling rocks, paper cranes and toner fade on ‘Missing’ posters. Gary Budden, Stephen Hargadon, Simon Avery and Lisa Tuttle contributed fine stores to horror magazine Black Static. I saw Prole for the first time even though it’s published more than twenty issues (I must catch up). I enjoyed Becky Tipper’s ‘The Rabbit’ in issue 20 and in 21 Richard Hillesley’s ‘Seacoal’ was wonderfully evocative and affecting. With Structo, Lighthouse and Confingo all continuing to surpass the high standards they have set themselves – Sarah Brooks’ ‘Aviary’ in Lighthouse 11 and David Rose’s ‘Impasto’ in Confingo 6 being among the highlights – our best short story writers are not short of outlets for their work. My favourite John Saul story of last year, ‘And’, appeared in Irish magazine Crannóg, but Confingo’s ‘Thirsty’ was also very good.

James Wall’s ‘Wish You Were Here’, which appeared online at Fictive Dream, was tight and masterful, its author completely in control of his material. Fictive Dream is more than worth a look for online short stories, likewise The Literateur. Jaki McCarrick’s story ‘The Jailbird’ was still available on the Irish Times website at the time of writing and Stuart Evers’ ‘Somnoproxy’, online at the White Review, is as beautifully written as his best work. On the airwaves last year, in addition to the two stories selected in these pages, Jenn Ashworth’s ‘The Authorities: A Modern Elegy’, for BBC Radio 4, was a powerful listen.

Two things I’ve learned during 2016:

Almost no one, anywhere, knows how to use the semicolon; I think I do, but I’m probably wrong.

Even though I have tried to keep an open mind on the issue, I can’t: ‘funny’ author biographical notes are never a good idea.1

The last word, last year, went to Dennis Hayward, who works on the tills at Sainsbury’s Fallowfield store in south Manchester. Dennis’s 2016 Christmas story was entitled ‘Christmas Cottage’ and raised £2500 for Foodbank, the charity having been chosen by customers of the store.

Nicholas Royle

Manchester

May 2017

There is, in fact, one exception to this rule: the author biog on the jacket flap of the first edition of Robert Irwin’s second novel, The Limits of Vision (1986), but it only really works with the author photo. You need to see it really.

Reversible

COURTTIA NEWLAND

London, early evening, any day. The warm black body lies on the cold black street. The cold black street fills with warm black bodies, an open-mouthed collective, eyes eclipse dark. Raised voices flay the ear. Arms extend, fingers point. Retail workers in bookie-red T-shirts, shapeless Primark trousers. Beer-bellied men wear tracing paper hats, the faint smell of fried chicken. There are hoods, peaked caps, muscular puffed jackets. There are slim black coats, scarred and pointed shoes, red ties, midnight blazers. A few in the crowd lift children, five or six years old at best, held close, faces shielded, tiny heads pushed deep into adult necks. New arrivals dart like raindrops, join the mass. Staccato blue lights, the hum of chatter. They pool, overflow, surge forwards, almost filling the circular stage in which the body rests, leaking.

A bluebottle swarm of police officers keeps the circle intact, trying to resist the flood. Visor-clad officers orbit the body, gripped by dull gravity; others without headgear stand shoulder to shoulder, facing the crowd, seeing no one. Blue-and-white tape, the repeated order not to cross. A half-raised semi-automatic held by the blank policeman who stands beside a Honda Civic, doors open, engine running. His colleague speaks into his ear. He is nodding, not listening. He looks into the crowd, nodding, not hearing. Blue lights align with the mechanical stutter of the helicopter, fretting like a mosquito. Its engine surges and recedes, like the crowd.

The blood beneath the body slows to a trickle and stops. It makes a slow return inwards. There’s an infinitesimal shift of air pressure, causing fibres on the fallen baseball cap to sway like seaweed; no one sees this motion. There’s a hush in the air. Sound evaporates. The body begins to stir.

One by one, the people leave. They do not hurry. They simply step into the dusk from which they came. The eyes of adults widen, jaws drop, mouths gape and snap closed. Children’s faces rise from shoulders, hands are removed from their eyes and they see it all. They crane their necks, tiny hands splayed starlike on adult shoulders.

The crowd step back. The uncertain suits, the puzzled office workers, the angry retail assistants. Chicken shop stewards, the cabbie, Bluetooth blinking in his ear. They step back until there is no one left but a trio of young men, Polo emblems on their chests, hands aloft, calling in the direction of the police.

The police shimmer and stir, lift and separate. Arms and legs piston hard, five officers backstepping faster than the crowd. They speed away from the body until they enter a parked ARV, three in the back, two in front. The vehicle gains life and roars into the distance. One of the remaining officers, a tall, gaunt woman, reels in blue-and-white tape, eyeing the young men with a glare veiled by an invisible sheen. When the tape is a tight blue-and-white snail in her hand, she also retreats, climbs inside a car with her partner, starts the engine and they roll away backwards. The visored officer joins his visored colleagues, where they gather like a bunched fist, semi-automatics raised and pointing.

The body lifts, impossibly. Ten degrees, twenty degrees, ninety; the fallen baseball cap flips from the ground, joins the head, and the man is half crouched as though he might run. He holds his left arm up, fingers reaching for sky, one bright palm facing the officers while his right hand clutches his heart. Drops of sweat fly towards his temples, as his head turns left, right. Thicker beads of red burrow into three puckered holes in his Nike windcheater, exposed beneath his fingers. He blinks one eye, as though he’s winking.

He is not.

Tiny black dots leap from his chest like fleas. Three plumes of fire are sucked into the rifle barrel. He stands and raises his right hand to his blinking eye, almost wipes, and then both palms are raised. He is shaking his head. His mouth is moving fast. His eyes are shifting quickly. Streetlights turn from orange to grey.

The young man is stepping into the Civic. The police officers are stepping across the street. The Polo youths on the opposite side of the road turn their heads, beginning to brag that road man’s time has come, and seconds after, of Wiley’s tweets about Kanye. They’re laughing. They have no idea. On the street, the young man drops his palms and crouches inside the Civic. He sits, puts his hands on the steering wheel and waits. The police officers stop shouting, they back further away. Beside the empty ARV, they lower their semi-automatics until the weapons are pointing at the dark street. Three get into the shadowed rear seat. Two climb in front. They roll backwards, away. The Polo youths reach the nearest corner. A flash of illumination from Costcutter lights, and they are gone.

The young man reaches down, starting the Civic. He puts the car in gear and its tyres turn anticlockwise, following the ARV; he could almost be in pursuit. He is not. He’s looking into the rearview, chewing on his inner cheek, a habit he has learned from his mother. He’s trying not to look at his blue-faced Skagen. A prickling disquiet, palms sparkling like moist earth; his hand lifts from the wheel and he marvels at this. He remembers; he must watch the road.

He wants to text his girl, but he’s afraid to pull over. He wants his right foot to fall, but knows where it will lead. Yards roll beneath him, and he stops paying attention, ignores his rearview mirror. There’s a song he doesn’t recognise on the radio. He taps the steering wheel in time. His palms are dry. He might even be singing; it’s impossible to tell. There are blue lights in every mirror. He hasn’t noticed.

Noisy blue dims into black silence, but he doesn’t see this either. Few pedestrians notice the ARV rolling backwards, or the baritone engine. Baseball-capped youths follow its passage, only tearing their eyes away as it leaves. Broad slabs of men duck towards the blank wall of shops, hide their faces, relax shoulders and return to upright positions. An elderly woman tries to loosen her spine, swivels too late and frowns, sensing a presence she can’t quite see, pulling her trolley towards her stomach. Schoolgirls in askew blazers and stunted ties, pink Nikes and petalled socks, lift their gaze from the pavement and become grim portraiture, before they retreat into a dusty corner store. The warped door shudders closed.

The young man palms the steering wheel anticlockwise, turns left. The sad-eyed windows of unkempt houses within an inch of dilapidation. The regressive spray of thick green hoses inside a hand car wash, a dormant hearse and driver. Mustard brick new-builds and the glow of a Metro supermarket, tired women stood on corners the closer he gets to home. They try not to stare in; he tries not to stare out. He does not see the green Volkswagen van creep behind him for another half-mile. He palms the wheel left again, backs into a dead-end street. The green Volkswagen slots onto the corner of his block. He passes by its idling rumble, eases into a residents’ bay, and shuts off his engine. Pats his pockets ritually to make sure everything is there. He gets out and stretches, bent backwards, reaching towards sky.

The sun on his cheeks, the occasional chilled breeze. Patchwork blue and grey above. The tinny chatter of a house radio, shouts of neighbours’ kids playing football. His windcheater flutters like a flag. There is tingling warmth inside him. It’s bathwater soft, soothing, and for one moment he smiles. He waves at the kids, who leap to their feet, yell his name.

Ray.

He is.

He doesn’t see the man on a street corner talking into his lapel. He misses urgent eyes that scan the road and fingers pressed against one ear. The lonely intent.

He enters the house, back and further back, immersed in turmeric walls, imitation pirates’ maps of back home, studio photos of himself, his mother and troublesome sister. He slows in the narrow passage. Smiles wider. His phone is pressed to his left ear, he’s grinning. It makes him look younger. The phone drops into his jeans pocket. He enters the kitchen.

His mother holds him close like a promise, one hand grasping the back of his head. Her eyes are shut. She rocks him in silence, as though he were still a boy. She knows and does not know. He is muttering about being late, but she refuses to listen. On the dining table a plate is dotted with rice shards and pink slivers of curried mutton, dull cutlery laid prone, fork cradling knife, a smudged glass sentry beside them. He wrestles from his windcheater and throws it onto the back of a chair. He sits.

General Impression of Size and Shape

ROSALIND BROWN

1

Attention snagged on the phone, lifted from flow of sentence. At window, sorry just a second, binoculars in one hand, dull light with heavy cloud, a fast dark shape with long tail, a few clean flaps and a flat glide. Checking against confusion species, especially kestrel, pigeon, collared dove and maybe even a question mark over peregrine, because after all they can fly, they migrate, never discount. All analysis done rapidly under the mind’s surface, like gravel fragments collecting in underwater drift. Mouth open usually for some reason. Builds in a series of yesses, warmer and warmer, until the word surges up and breaches into clean air. Sparrowhawk.

Pre-dinner drinks in garden, chilly September, cardigans around shoulders. Then a quick movement above, face tilts back to evening sky. So does another face. Four small liquid-flying birds, forked streamers, glamorous and chasing and chattering, going south. Textbook swallows. Politely both back into the conversation.

* * *

A set of well-worn routes in the brain. Necessary often for the speed of it. Something springs out of a tree and the sense of it being dark grey and long-legged and in a rush is all you’ve got. Or maybe an instant of a white rump in the sun and that’s a certainty.

Or at the other end of the spectrum, seeing it relaxed and taking up a position in a distant bush. Too far even for binoculars, keep them up ready at face and creep forward with blind feet, hoping no sudden rough terrain. Body not dealing well with such tight control, threatens to break out in spasms, shoulders already tired. The classic nightmare, having the bins up and deciding to bring them down, or bins down and deciding to bring them up, and sometime between defocusing eyes and refocusing eyes, it’s gone. Not unusual in that scenario to call a bird a wanker.

Attention goes now not only to pointed wings scaring pigeons in the market square, but also to a certain model of red Volkswagen estate, even many miles from home. Strain eyes following it away down the road. Numberplate, no.

What are you looking at? Oh, nothing.

Peregrine falcon population of UK estimated at maybe 2,000 breeding pairs. All with that look in their eye, wild alertness, tingeing into fear. One on a rock halfway down a headland in Cornwall, underline the words also on cliffs in lowlands in bird book and draw neat little smiley face. One hassling two golden eagles in Scottish highlands, deliriously good sighting. And one in town on the church, quick phone call and rendezvous under the spire, wow nice one, bird being photographed against its knowledge, so how are things, then leaps off its gargoyle and speeds away on its own obscure business, bugger, maybe it’s camera-shy. Flash of a smile, not looking up from inspection of photos. End of lunch break, both back to offices. Watching inbox like a (ha ha) hawk after that.

Early dark morning, treading together, not speaking, cloudy breath barely visible. Sitting in the hide, serene chill water and golden reeds all around. Sun seeps in. Those important weekday times, 7am 8am 9am, melt together waiting for bitterns. At long last, utterly against expectation, one of the reeds emerges and is the thing itself, hunched and stealthy. Tiptoes, tip-talons. Breathing triumphant words, binoculars rigid with focus.

All across the county, people making coffee in morning kitchens, grubby with sleep, empty birdfeeders in gardens. Here in the hide, the construction of something else entirely, bit by bit, bittern by bittern.

Lay down thousands of sightings in your mind, build them up like a dry stone wall. A knowledge so hyper-specific it will enable you to hear the chipping from the hawthorn and not even need to think the names of robin and wren before you start to work out which one, and simultaneously listen for that otherness in the sound which might make it blackcap. Like piano exercises, get countless banalities under your belt, woodpigeons from every angle, mallards in all mutant plumages, so you’re ready for the greats. The curlew in breeding season sending a long wail over drenched moorland. A vast starling murmuration suddenly contorting and bunching away from a predator and it really is a peregrine, everywhere at once, plunging in and out of the chaos. Hands placed on shoulders in the gloom and gently manoeuvring round to see a barn owl ghosting over the reeds in front of you, so definite and white, and behind you a warmth neither white nor definite.

An eagle rises above the ridge, closer than you thought it would dare, your stomach collapses, it fixes you with its bleak and alien mind.

One day perhaps will be able to glide over the top of these memories like a gannet skimming the waves, spears of pure white for wings. For now, like a blackbird foraging in dead leaves, jumping and jerking and making an unnecessary commotion.

A light lace of waxwings falls over the countryside wherever there are berries, fieldfares rattle off insults to each other, redwings are speckled and shy on the ground. And together miles and miles of road in three or four different counties, hours and hours of music on the car stereo, with attendant good-humoured arguments about bad taste. Hen harriers, pale shapes gliding wearily in to roost, and that concludes business for the day. Slow and shivering walk back to car, awkward binoculars clashing in hugs, what time do you need to be back, it’s fine, she won’t get suspicious for a while yet. One delicious half-hour whisky later and murmured fantasies about eloping to America, they have hummingbirds there, faces close enough to feel the heat in his cheeks, laughing at stories about swans attacking cyclists, a pub in a village whose name won’t be remembered, just a straight fenland road and a huddle of houses and a camera full of photos and a mind full of dopamine. It’s so strong, you know, that dopamine, it can break your arm.

2

Spring begins to force its way up, message forums explode briefly, reed warblers and sand martins and wheatears, until all arrivals accounted for. Simple pleasure of a soft greenfinch screech across an evening park. Nest-building and crazed all-day singing and territorial fly-bys from chaffinches more pink than a squashed finger. Feathery shit from willows breezing over the path, gathering in clumps. Marsh harriers courting, the renowned food pass, the female twisting herself upside down to catch the vole from her mate. Sturdy retired women into hide, depositing special lightweight telescopes, removing no-rustle coats, lifting binoculars, oh isn’t that marvellous. Young fair-weather couples in denim jackets and inadequate footwear and no bins. Kids interested in basically nothing except shouting again and again the word BIRD.

Still reeling from very painful conversation which the mind insists on holding up like a banner, deserted early morning café, the guilt-pecked eyes characteristic of the adult(erous) male, so awful if she discovered, trembling and speechless, table abandoned with one empty cup and one only half-drunk. All day desolate at desk. Allowed still to be friends of a kind, accompanying each other on trips to see red-footed falcon, penduline tits, single Savvi’s warbler, all rarities, feckless and exhausted and hundreds of miles out of normal range and therefore on the receiving end of hundreds of long lenses bigger than a man’s face.

Collective nouns for the various developments. An exultation of larks, certainly not. A fling of sandpipers, well, perhaps, but a bit late for that now. A charm of finches, same. A quarrel of sparrows, a confusion of guinea fowl, a pretence of bitterns, it’s in there somewhere. Anyway, for official things, go through his assistant now.

Different approaches, all valid. Know all the Latin names and proper terminology, primaries, coverts, supercilium, eclipse plumage, build up an exhaustively tagged database of photos. Or read about the soft stuff, the merlin was a lady’s falcon, bitterns were once hunted in fenlands and cooked in pies, red kites in Shakespeare’s day were as common in filthy cities as gulls are now. Also, swifts do not land for two years after fledging, they sleep on the wing. Their reality is the spaces between things. The sight of them going in shallow circles, adding a stratum to the clear spring sky, screaming contentedly. Materialising right in front of the car, heading straight for the windscreen, before skimming up and over the roof at the last second, and two sets of held-breath laughs and one pair of hands squeezing together above the handbrake, heads turn towards each other, don’t think this is a good idea, hands detach, shamefaced reluctance, it wouldn’t be wise to get into that again.

Dropped off back at own car hidden on side street, first decision is whether to cry before going home, or to save it for soundless wet stretching-open of mouth later in dark bed.

Two young friends get together, both seventeen, hands timidly touching and arms around waists, watching them with real jagged thoughts inside, both with hair so translucent it’s practically colourless, expressions of unadulterated, wholesome, thoroughly deserved joy.

Spin the wheel of who will receive desperate sobbing phone call today, who will dispense advice to be ignored, who will nonetheless continue to send patient and sympathetic messages. Unanimous bewilderment about why contact is being maintained, why more meetings, and yes, of course, you’re right, but unthinkable to give him up, like ripping out a lark’s lungs.

Those early day songs only played now for forcing relief, like turning on the tap for a stubborn bladder. Sunday afternoon in a shop, holding a shoe, raw singer-songwriter voice over the speakers, endure it perhaps, three minutes at most, thoughts winding tighter and tighter, then suddenly, no, get the fucking hell out. In the street, starlings all cocky, swinging their little shoulders and darting for bits of dropped baguette.

Paraphernalia in pockets, chocolate bar wrappers, species lists from the big reserve, gloves, unidentified plastic bit broken off binoculars, old tissue, waxy, no longer sodden.

Even more of the same, seven-hour stretches, waiting before six with the sun already high, elbows and binoculars propped on car, spotting skylarks, then the one and only red VW speedbumping into the car park, unshaven greeting, out on the road again. Or the afternoon into evening, low sun, shrieking of baby birds and glimpses of mad open mouths, cuckoos thinking about returning to Nigeria, sudden airborne squirt of shit. Then onto final destination through growing darkness, dead-end road, headlights off, coats on, jokes about being afraid of the dark and no really it is quite spooky, finding out the furious purring of nightjars.

Back in the car with completed checklist, getting on for eleven at night, no surprises when conversation turns dangerous again, pauses lengthening, voices softening. Eventually, lay-by. Making the beast with two jesus did you hear that owl. Both faces twist round to see tubby silhouette flapping away in disgust.

3

Alone for months now. Light always seems to be coming or going, always a complicated pattern of black bare twigs against a gradient of twilight sky.