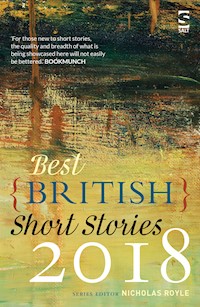

Best British Short Stories 2018 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor's brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume. This new anthology includes stories by Colette De Curzon, Mike Fox, David Gaffney, Brian Howell, Wyl Menmuir, Adam O'Riordan, Adrian Slatcher, William Thirsk-Gaskill, Chloe Turner, Lisa Tuttle, Conrad Williams, among others.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 360

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BEST BRITISH SHORT STORIES 2018

edited by

NICHOLAS ROYLE

SYNOPSIS

The nation’s favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its eighth year.

Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor’s brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume.

This new anthology includes stories by Owen Booth, Kelly Creighton, Colette de Curzon, Mike Fox, M. John Harrison, Tania Hershman, Brian Howell, Jane McLaughlin, Alison MacLeod, Jo Mazelis, Wyl Menmuir, Adam O’Riordan, Iain Robinson, C. D. Rose, Adrian Slatcher, William Thirsk-Gaskill, Chloe Turner, Lisa Tuttle, Conrad Williams and Eley Williams.

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS WORK

‘For those new to short stories, the quality and breadth of what is being showcased here, will not easily be bettered. Moreover, the experiential difference that contemporary short stories offer, when compared to novel reading – the unique register they can strike – makes this collection all the more valuable.’ —Bookmunch

‘When an anthology limits itself to a particular vintage, you hope it’s a good year. The Best British Short Stories 2014 from Salt Publishing presupposes a fierce selection process. Nicholas Royle is the author of more than 100 short stories himself, the editor of sixteen anthologies and the head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, which inspires a sense of confidence in his choices. He has whittled down this year’s crop to 20 pieces, which should enable everyone to find a favourite. Furthermore, his introduction points us towards magazines and small publishers producing the collections from which these pieces are chosen. If you like short stories but don’t know where to find them, this book is a gateway to wider reading.’ —LUCY JEYNES, Bare Fiction

‘It’s so good that it’s hard to believe that there was no equivalent during the 17 years since Giles Gordon and David Hughes’s Best English Short Stories ceased publication in 1994. The first selection makes a very good beginning … Highly Recommended.’ —KATE SAUNDERS, The Times

‘Another effective and well-rounded short story anthology from Salt – keep up the good work, we say!’ —SARAH-CLARE CONLON, Bookmunch

‘Nicholas Lezard’s paperback choice: Hilary Mantel’s fantasia about the assassination of Margaret Thatcher leads this year’s collection of familiar and lesser known writers.’ —NICHOLAS LEZARD, The Guardian

‘This annual feast satisfies again. Time and again, in Royle’s crafty editorial hands, closely observed normality yields (as Nikesh Shukla’s spear-fisher grasps) to the things we ‘cannot control’.’ —BOYD TONKIN, The Independent

‘For those new to short stories, the quality and breadth of what is being showcased here, will not easily be bettered. Moreover, the experiential difference that contemporary short stories offer, when compared to novel reading – the unique register they can strike – makes this collection all the more valuable.’ —Bookmunch

Best British Short Stories 2018

NICHOLAS ROYLE has published three collections of short fiction: Mortality (Serpent’s Tail), shortlisted for the inaugural Edge Hill Short Story Prize in 2007, Ornithology (Confingo Publishing), longlisted for the same prize in 2018, and The Dummy & Other Uncanny Stories (The Swan River Press). He is also the author of seven novels, most recently First Novel (Vintage), and a collaboration with artist David Gledhill, In Camera (Negative Press London). He has edited more than twenty anthologies, including seven earlier volumes of Best British Short Stories. Reader in Creative Writing at the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University and head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, he also runs Nightjar Press, which publishes original short stories as signed, limited-edition chapbooks.

Also by Nicholas Royle:

NOVELS

Counterparts

Saxophone Dreams

The Matter of the Heart

The Director’s Cut

Antwerp

Regicide

First Novel

NOVELLAS

The Appetite

The Enigma of Departure

SHORT STORIES

Mortality

In Camera (with David Gledhill)

Ornithology

The Dummy & Other Uncanny Stories

ANTHOLOGIES (as editor)

Darklands

Darklands 2

A Book of Two Halves

The Tiger Garden: A Book of Writers’ Dreams

The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories

The Ex Files: New Stories About Old Flames

The Agony & the Ecstasy: New Writing for the World Cup

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing

The Time Out Book of Paris Short Stories

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing Volume 2

The Time Out Book of London Short Stories Volume 2

Dreams Never End

’68: New Stories From Children of the Revolution

The Best British Short Stories 2011

Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds

The Best British Short Stories 2012

The Best British Short Stories 2013

The Best British Short Stories 2014

Best British Short Stories 2015

Best British Short Stories 2016

Best British Short Stories 2017

To the memory of Colette de Curzon 1927–2018

Nicholas Royle

Introduction

A very short introduction this year, because there was, as you no doubt remember, only one short story published during 2017 and that was ‘Cat Person’ by Kristen Roupenian, which went viral on social media after its appearance in the New Yorker. A unique alignment of popular opinion, media frenzy and hashtag bingo made it virtually impossible to express any opinion of ‘Cat Person’ other than unreserved, drooling approval.

Oh, all right then, there were some other stories published last year, but you wouldn’t think so from Prospect magazine’s ‘Winter Fiction’ supplement, dated January 2017, which devoted seven of its twelve pages to extracting Peter Hobbs’s story, ‘In the Reactor’, from the Faber anthology he had edited with Sarah Hall, Sex & Death, in 2016.

There were, however, lots of notable anthologies published during 2017, including, among many others: New Fears, a major new horror anthology edited by Mark Morris for Titan Books, the first of a new series; She Said He Said I Said: New Writing Scotland 35 (Association For Scottish Literary Studies) edited by Diana Hendry and Susie Maguire; Tales From the Shadow Booth Volume 1 (no publisher given; I especially enjoyed Timothy J Jarvis’s ‘What the Bones Told Hecate Shrike’) edited by Dan Coxon; Ruins & Other Stories (Cinnamon Press) edited by Adam Craig; Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology Volume 10 (Tangent Books); The Mechanics’ Institute Review edited by an extensive team at Birkbeck, with excellent stories by Alan Beard and Sarah Evans; Unthology 9 (Unthank Books) edited by Ashley Stokes and Robin Jones (I loved Roelof Bakker’s ‘Yellow’); New Ghost Stories III (The Fiction Desk) edited by Rob Redman; The Bridport Prize Anthology 2017 (Redcliffe Press) with an outstanding second-place winning story, ‘Ends’, by Chris Neilan; and three issues of The Lonely Crowd, described on its web site as a ‘literary journal’ although each issue is an ‘anthology of new short fiction, poetry and photography’ – but who cares about minor details of nomenclature when the editor (John Lavin in this case) has such great taste and publishes so much good work?

The highlights of last year’s Lonely Crowd issues may – or may not, according to taste – be the stories reprinted in this book (by Kelly Creighton, Iain Robinson, Jo Mazelis and CD Rose), but number six included stories by Neil Campbell and John Saul, who are always interesting, while in number seven I liked Durre Shahwar’s ‘Nowadays’ and Eley Williams’s ‘Channel Light Vessel Automatic’, and number eight in particular was packed with good stories by Jenn Ashworth, Thomas Morris, Jane Fraser, Angela Readman, Giselle Leeb, Jaki McCarrick, David Rose, Toby Litt and others. Gorse continues to publish probably the most attractive journal-anthology in these islands, each issue bursting with envelope-pushing fiction, poetry and essays. Issue eight contained an excellent story by David Rose, ‘Translation’, riffing and punning on the problems facing any literary translator, and an interesting piece by Hugh Smith, ‘John 1.1’.

The good magazines keep on publishing good stories. For this we must be thankful to Ambit, Anglo Files, Bare Fiction, Black Static, Brittle Star, Confingo, Lighthouse, Structo and others. Two stories in Ambit 230 stood out for me: Tom Heaton’s ‘The Writer Didn’t Know the Pen Was Still Writing’ and Paul Brownsey’s ‘Time and the Heart’ (Brownsey’s ‘Peace and Goodwill’ in issue 22 of Scottish literary journal Southlight was notable, too). Ghostland was new to me; it feels net-based, with the editorship credited to Twitter handle @havishambler, but exists only as a print zine. Painted, spoken edited by Richard Price had reached issue 29 before I came across it (thanks to David Rose’s recommendation); it appears ‘occasionally’. I enjoyed Bill Broady’s story ‘The Man Who Broke the Bank’. For more information go to hydrohotel.net. Speaking of hotels, I think I’d like to live in Hotel edited by Jon Auman, Holly Brown, Thomas Chadwick, John Dunn, Dominic Jaeckle and Niall Reynolds. They seem to add a name or two to that list with every issue, so I hope I’m more or less up to date. The first issue came out in 2016 and I’m really quite cross with myself for missing it, but I’ve got issues two and three, which came out in 2017. It feels like a cousin of Ambit, and Ambit had better watch out, because Hotel is very good.

It was a strong year for short story collections, with new titles from Alison MacLeod, Martyn Bedford, Tania Hershman, Eley Williams, Leone Ross, Conrad Williams, M John Harrison, Adam O’Riordan, Joanna Walsh, Lucy Durneen, Mike O’Driscoll, Erinna Mettler, Michael Stewart and others. Stories from some of these are included in the present volume. The story that spoke most clearly and poignantly to me in Gregory Norminton’s collection, The Ghost Who Bled (Comma Press), was the title story, which I remember reading for the first time in Prospect magazine in 2004. Joanna Walsh’s new collection, Worlds From the Word’s End (And Other Stories), reprints stories first published between 2013 and 2016, but, unless I’m misreading the acknowledgements, did not include any new work.

Stonewood Press published When You Lived Inside the Walls, a lovely little mini-collection of three stories by Krishan Coupland, including his Manchester Fiction Prize-winning story from 2011. Among the British writers shortlisted for the same prize last year were Jane Fraser, Hannah Vincent and Dave Wakely. Their stories were published online.

Also online I came across a fine story by Jaki McCarrick, ‘The Collectors’, on the Irish Times web site and, on – or should one say at? – Music & Literature, I read, with mounting excitement, a piece called ‘I Went to the House But Did Not Enter’ by Paul Griffiths. Mounting excitement because it was the best thing I’d read for some time and had been created as a piece of experimental writing under a set of constraints. It’s always rather wonderful when constraints appear to have a liberating effect. Sadly, I discovered it had been first published, elsewhere, some years earlier, making it ineligible for inclusion in this book.

The Galley Beggar Press Short Story Prize 2017/18 longlist included ‘Cluster’ by Naomi Booth, in which a sleep-deprived mother observes and tries to connect with her surroundings. There’s something moving about the realisation that she’s not the only person who called the police over an incident of domestic abuse she witnesses. ‘Other people have called too,’ the call handler tells her. Robert Mason, previously shortlisted for the Manchester prize, made the Galley Beggar shortlist with ‘Curtilage’, a disturbing story about a man who preys on vulnerable targets. What makes those two stories stand out is their attention to detail. Detail is not always necessary and quite possibly it often needs to be cut, but in these stories it’s what elevates them.

There’s something especially pleasing about short stories – especially good short stories – turning up in unusual places. Issue 102 of Pipeline: The Journal of Surfers Against Sewage, a handsome, full-colour 60pp A5-size magazine, contained an original environmental ghost story, ‘The Gyre’, by Man Booker Prize-longlisted author Wyl Menmuir, who also features in the current volume with a story published in chapbook format by the National Trust, the launch title for a series of such publications.

TSS Publishing, run by Rupert Dastur, started publishing short story chapbooks in 2017, with three titles by Sean Lusk, Chloe Turner (reprinted herein) and Matthew G Rees. They are attractive, small-format booklets, uniformly designed and numbered. Nightjar Press (founded in 2009 by the editor of the book you may be holding in your hands if you are reading these words) entered its tenth year of publishing with new chapbooks by Claire Dean, David Wheldon and Colette de Curzon. ‘Paymon’s Trio’ by Colette de Curzon was written in 1949 when its author was 22. She put it away in a folder of her work where it stayed for 67 years until one of her daughters, the novelist Gabrielle Kimm, found it and was advised by Alison MacLeod to send it to Nightjar Press. Thanks partly to the enthusiasm of poet and artist David Tibet, who championed and recommended the story to his many followers, it became one of Nightjar Press’s fastest-selling titles. It is reprinted in the current volume, which is dedicated to the memory of Colette de Curzon, who sadly passed away in March 2018.

Chapbooks are not a new phenomenon. Indeed, an article about them by Ruth Richardson on the British Library web site is written entirely in the past tense. Just lately I have been reading (and rereading) a lot of Giles Gordon’s fiction, including his alarming short story ‘Couple’, published exclusively as a chapbook by Sceptre Press of Bedford in 1978. I have written about Gordon before in one of these introductions. People sometimes say to me, ‘Giles Gordon, he used to edit that series you’re editing now,’ or some variation on that, because he co-edited a series called Best Short Stories, which ceased publishing in 1994, while this series started in 2011, under the very obviously different title Best British Short Stories. That was years before anyone ever uttered the hideous word ‘Brexit’, but every year I work my way through magazines and anthologies reading only stories by British authors and ruthlessly ignoring work by Americans and Australians and writers of other nationalities even if they are writing in English. I feel as if I’m locked into some awful rotten marriage of bitter inconvenience with Nigel Farage or Jacob Rees-Mogg, or Theresa May, for that matter, or even David bloody Cameron, whose responsibility it all surely is. As if I were, like some of the above, motivated by isolationism and xenophobia and misplaced patriotism. Four previously unpublished stories by Raymond Carver’s editor Gordon Lish in the third issue of Hotel? Any sensible person would be all over them. But pressure of time means I generally limit myself to the British contributors in any publication of this type.

When we started Best British Short Stories there was already a Best British Poetry, so it made sense to stick to the British-only rule. Since then the Man Booker Prize has, regrettably, been opened up to American writers, which in a way makes one happy to remain British-only with this series, but then there is Brexit. There is always Brexit. Unless, of course, it doesn’t happen. I live in hope.

Nicholas Royle

Manchester

May 2018

colette de curzon

Paymon’s Trio

I had always been fond of music: it was a kind of passion in me, around which I centred my whole existence, and in the beauty of which I derived all the pleasures I required from life. I was well up in anything and everything connected with music, from the earliest and most primitive of rondos to the latest symphonies and concertos. I played the violin passing well, though my ability of execution fell far short of my desires. I had played second violin in various concerts, provincial ones, of course, for a natural shyness prevented me from daring to launch my meagre talent into higher spheres. Besides which, the violin for me was not a profession: it was merely a friend in whom I confided all the thoughts and emotions of my soul, which I could not have expressed in any other way. For even the most retired of men needs to express himself in one way or another.

I had always connected music with the beautiful side of life. In this, for my fifty-odd years, I was strangely naïve. The experience I went through shook the rock-solid foundation of my innocent belief. It will, no doubt, be hard for anyone reading this story to believe it all, or even any part of it; but I am here to testify that every word of it is true, I and my two very dearest and noblest of friends, for we all three went through the same experience, and all three unanimously declare that every word of it is solid fact. A few years have elapsed since the evil day that brought a passing shadow on my life’s passion, but the memory of it is still fresh in my mind.

I will start at the beginning and try to impart all its vividness up to you.

It was on a raw November’s evening, with dusk swiftly descending on windswept London, as I was returning from Hyde Park, where I had taken my dog, Angus, for his afternoon exercise, that I suddenly remembered I had gone out for a double purpose: the first already mentioned, the second a half-hearted quest for a second-hand copy of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. To say that I was interested in that work would be a great exaggeration. I had heard various reports about it that did not rouse my enthusiasm, but as it had got a new vogue and was much talked of, I wished to acquaint myself of its content, so as to know, roughly, at any rate, what it was about.

I prided myself on being erudite – such puny accomplishments are very satisfactory – and my ignorance concerning Burton’s work was a serious lapse in my literary learning. So, Melancholy bound, I made my way down some narrow side streets, ill-lit by bleary lampposts, where I knew I would find a number of barrows of second-hand books, and where I hoped to find the work in question. The first two barrows revealed a great deal in the nature of melancholy, but not Burton’s. At the third, which was overshadowed by the towering bulk of a surly woman vendor, who eyed me as suspiciously as though I were a notorious nihilist, I found the book I was looking for. Or books – for it was in three volumes. But they were wedged behind a tall black volume which I found necessary to remove in order to reach them.

I daresay I was clumsy, or perhaps Angus chose that particular moment to tug on his leash and jerk my arm. At any rate, Angus or no Angus, my hand slipped from the black book which, having been dislodged, fell with a thud on to the muddy pavement, its binding being badly stained in the process. I remember thinking, in spite of my vexation, that the fat woman was no doubt proud of having suspected me of evil intentions from the start, for I was certainly proving myself to be no ordinary customer.

I picked up the book, and seeing how badly damaged it was, I thought it only civil of me to buy it off her, though many of her books were in more distressing conditions. She accepted my offer grudgingly, and had the impudence to charge me an extra 6d on the original two shillings. Being hardly in a position to argue, I allowed her to engulf my half crown and departed with my new acquisition under my arm . . . and the Anatomy still skulking dismally in its barrow.

When I got home to my flat – which I shared with my most faithful and congenial of friends, Arnold Barker, with whom I had seen two wars and a prison camp in Germany – I inspected the book I had just purchased. Arnold was out at the time, so I had the flat all to myself. I dreaded so the fearful trash which would have disgraced my library – some cheap romance that would make me shudder. But the binding calmed my fears: no romantic author would have chosen thick black leather to garb his story. The title in gold print was hardly discernible.

I opened the book and felt a little shiver of pleasant anticipation run down my spine. In bold black lettering, ornamented with fantastic arabesques à la Cruikshank, the title displayed itself to my eyes: Le Dictionnaire Infernal by J Collin de Plancy, 1864. It was in French, which pleased me all the more, as my knowledge of that language was more than fair, and it was full of weird, humoristic and infinitely varied engravings by some artist of the middle of the last century.

I perused it avidly and rapidly acquainted myself of its contents. An Infernal Dictionary it was, written in a semi-serious, semi-comical style, giving full details concerning the nether regions, rites, inhabitants, spiritualism, stars reading, fortune telling etc, which, as the author informed us, all had to be taken cum granu salis. I hasten to say that I in no way dabbled in demonology, but this book, though certainly dealing with the black arts, was harmless to so experienced a reader as myself. And I looked forward to several days of pleasant entertainment with my unusual discovery. I pictured Arnold’s face as I would show him my find, for the occult had always fascinated him.

I skimmed the pages once more, smoothing out those which had been crushed in the fall – or perhaps before – when my fingers encountered a bulky irregular thickness in the top cover of the book. The fly leaf had been stuck back over this irregularity, and gummed down with exceedingly dirty fingers.

To say that I was puzzled would of course be true. But I was more than puzzled: I was very intrigued. Without a moment’s hesitation, I slipped my penknife along the gummed fly leaf and cut it right out; a thin piece of folded paper slipped out and fell onto the carpet at my feet. What made me hesitate just then to pick it up? Nothing apparently, and yet fully ten seconds elapsed before I took it in my hand and unfolded it. And then my enthusiasm was fired, for the folded sheets – there were three of them – were covered with music: music written in a neat, precise hand, in very small characters, and which to my experienced eyes appeared very difficult to decipher.

Each sheet contained the three different parts of a trio – piano, violin and cello. That was as far as I was able to see – for the characters being very small and my eyes not so good as they had been, I could not read very much of it. I was, however, thrilled; childishly, I must confess, I hoped – even grown men can be foolish – that this might be some unknown work from a great composer’s hand. But on second perusal, I was quickly disillusioned. The author of this music had signed his name: P Everard, 1865, which told me exactly nothing, for P Everard was quite unknown to me.

The only thing that intrigued me considerably was the title of the trio. Still in the same neat hand, I saw the skilfully drawn figure of a naked man seated on the back of a dromedary, and read, ‘In worship of Paymon’ underlining the picture.

It may have been a trick of the light, or my imagination, but the face of the man was incredibly evil, and I hastily looked away.

Well, this was a find! However obscure the composer, it was interesting to find a document dating back to the nineteenth century, so well preserved and under such unusual circumstances. Perhaps its very age would make it valuable? I would have to interview some authorities on old manuscripts and ascertain the fact. In the meanwhile, the temptation being very great, I set about playing the violin part on my fiddle. My fingers literally ached to feel the polished wood of my instrument between them and I was keenly interested at having something entirely new to decipher.

Propping up the violin part on my stand – the paper, though thin, was very stiff and needed no support – I attacked the opening bars. They were incredibly difficult and at first I thought I would not be able to play them, although I can say without boasting that I am more than a mere amateur in that respect. But gradually I got used to the peculiar rhythm of the piece and made my way through it. Strangely enough, however, I felt intense displeasure at the sounds that were springing from my bow. The melody was beautiful, worthy of Handel’s Messiah, or Berlioz’s L’Enfance du Christ, for it was religious. Yes, religious: and at the same time it seemed only to be a parody of religion, with an underlying current of something infinitely evil.

How could music express that, you may wonder. I do not know, but I felt in every fibre of my body that what I was playing was ‘impure’ and I hated as much as I admired the music I was rendering.

As I attacked the last bar, Arnold Barker’s startled voice broke in my ear. ‘Good God, Greville, what on earth is that you’re playing? It’s terrible!’

Arnold, in all his six-foot-three of ageing manhood, brought me out of my trance with his very material and down-to-earth remark. I was grateful to him. I lowered my fiddle.

‘Well, I daresay it could be better played,’ said I, ‘but it is amazingly difficult.’

‘I don’t mean you played it badly,’ Arnold hastily interposed. ‘Not by a long chalk. But . . . but . . . it’s the music. It’s wonderful, but extraordinarily unpleasant. Who on earth wrote it?’ He took off his mist-sodden coat and hat, and picked up one of the two remaining sheets of music.

As he scanned it, I explained my little adventure, and how I had come into possession of the unusual manuscript.

The book did not appear to rouse much interest in him: his whole attention was centred on the sheet of paper he was holding. As I was finishing speaking, he said, ‘This appears to be the piano part: I could try my hand at it, and accompany you. Though, as you say, it appears to be extraordinarily difficult . . . the rhythm is unusual.’

He was puzzled as I had been, and I watched him as he seated himself at the piano and played the first opening bars. He was a born pianist: these short competent hands, as they stretched nimbly over the keys, were sufficient proof of that. The only defect in his talent that had prevented him from making a career of it was his deplorable memory and total incapacity to play anything without the music under his eyes. Now, he did not appear to find his part difficult – not as I had done. Of course, the piano, in this trio, merely featured as an accompaniment, a subdued monotone which now and then picked up the main theme of the piece and exercised variations upon it.

Arnold played the piece half-way through, then stopped abruptly. ‘Of course my part is rather dull,’ said he. ‘It needs the violin and the cello to bring it out. But, well . . . I don’t mind admitting that I don’t like it. It’s . . . uncanny . . .’

I nodded in agreement.

‘What do you make of the man’s name?’

‘Nothing.’

‘As far as I can tell, the name Everard has never become famous in the music world, and yet the man was gifted, for this piece has rare qualities. It reminds one of some strains of The Messiah, and yet . . . well, there’s just that something in it that makes it all wrong.’

‘It’s peculiar,’ I admitted. ‘Extraordinary luck my finding it. I suppose it has been in the binding of that book since the date when it was written. But why was it . . . well . . . I should say “concealed”? I can’t think. And what about that dedication? Who is Paymon?’

Arnold bent closer to the picture, and I noticed him suck in his breath as in some surprise. He straightened himself up and cast me rather a furtive look. ‘I don’t know,’ he mused. ‘Paymon . . . and “in worship” too. Somebody this fellow Everard must have been frightfully fond of. But have you noticed the expression on the man’s face? It’s rather unpleasant.’

‘Evil is more like it – the man was an artist as well as a musician. It’s very odd. I will have to take this manuscript to old Mason’s tomorrow and see what he can make of it. It may have worldwide interest for all we know.’

But, the following day being a Sunday, I did not care to trouble my old friend with my mysterious manuscript, and I spent my time, much to my reluctance, practising my part of the trio. It fascinated me, and yet repelled me in every note I drew across the strings. When I looked at that small, hideous picture, I felt as though a cunning little devil had got inside my fingers and compelled me to play against my will, with the notes dancing and jumbling before my eyes, and the weird strains of the music filling my head and making me loathe myself for yielding to that strange force.

Late in the afternoon, Arnold, who had been strangely moody as he listened to me from the depths of his favourite armchair, rose to his feet and came over to where I was playing. ‘Look here, Greville,’ said he. ‘There is something definitely wrong with that music. I feel it, and I know you do too. I can’t analyse it, but it is there all the same. We ought to get rid of it somehow. Take it to Mason’s and tell him to do what he likes with it, or burn it, but don’t keep it.’

I was stubborn. ‘It may have its value, you know,’ I remonstrated. ‘And, after all . . . it’s really beautiful.’ And I wondered at myself for praising something which I loathed with all my heart.

‘Yes, it’s beautiful. But it’s bad. Don’t lie to yourself – you think so too. I have been watching you all the time you were playing, and by Heaven, if anyone seemed to be in absolute terror of something, that person was you. That thing’s infernal – I’ve a good mind to destroy it here and now!’

He seized the three sheets that were lying on the violin stand and made as though to throw them into the fire. But I stayed his hand and murmured quite feverishly (and quite, it seemed, against my will), ‘No! Not just yet. After all, it’s a trio, and we have only played two parts of it. If we could get Ian McDonald to come round this evening with his cello, we could play the whole thing together – just once, to hear it as it should be played. And then . . . well . . . we can destroy it.’

‘Ian? That boy will be scared stiff!’

‘Scared? Of what? Of a few notes on a sheet of paper eighty-five years old? You’re being foolish, Arnold. We both are. There’s nothing wrong with the music at all. It’s weird, uncanny perhaps, but that’s all that’s to be said against it. So is Peer Gynt for that matter, and yet no-one would dream of being scared by it, as we are by this trio . . .’

Arnold still looked very doubtful, so I pressed my point.

Why, I wonder now . . . why was I so eagerly enthusiastic about my find, when deep down in my mind I felt a lurking fear of it, as of an evil thing that polluted whatever it touched? I detested it, and yet that little naked figure on the dromedary’s back held my senses in a kind of spell and made me talk as I was now doing: without my being able to control my thoughts and voice as I wished.

‘After all,’ I argued, ‘this is my discovery, and it’s only natural that I should wish to know what the whole effect of the trio is like. As we’ve played it – you and I – it was, well, lop-sided. It needs the cello to complete it. And, you said yourself when you first heard it that it was beautiful!’

‘And ghastly,’ Arnold added sulkily, but he was clearly mollified. He perused his part of the trio once more.

On the three sheets was repeated the detestable little figure, and I noticed that Arnold kept his hand carefully over the wicked face, and on replacing the sheet on the music stand, he averted his eyes. So, that drawing held that strange influence over him, too? Perhaps . . . perhaps . . . there was something after all.

But Arnold prevented any further speculation.

‘All right,’ he said, in a resigned voice. ‘I’ll go round and collect young Ian. But remember, I take no responsibility.’

‘Responsibility? What responsibility?’ I asked.

Arnold looked embarrassed. ‘Oh, I don’t know. But if . . . well . . . if this blasted trio upsets the lot of us, I want you to know that I wash my hands of the whole thing from this very minute.’

‘Don’t be a damned idiot, Arnold,’ I said with some heat. ‘I never knew you to be so ridiculously impressed by a piece of music. You’re as silly as a five-year-old child!’

I felt my inner thoughts battling against the words I uttered.

The little man on the paper seemed to grin at me, and I suddenly felt physically sick. I turned to stop Arnold, but he had already left the room, even as I opened my mouth to speak to him. I heard the clang of the front door as he slammed it. I regretted my insistence. I hated myself for having persuaded Arnold to fetch Ian, and, obeying a sudden impulse, I seized the papers and prepared to throw them into the smouldering fire. The little man’s eyes on the paper followed mine as I moved, as though daring me to carry out my intention. I stopped and stared at the grinning face . . . and I replaced the sheets on the music stand, with a thrill of unpleasant fear running down my spine.

Arnold was away some time. When he came back, he had brought Ian with him and between them they carried the latter’s cello – a very beautiful instrument in a fine leather case. Ian, compared to both of us, was a mere child: he was barely twenty-eight, with a gentle, effeminate face and a weak body that was greatly at a disadvantage beside Arnold’s towering strength and healthy vitality. But he was a fine fellow for all his physical deficiencies, and in spite of the difference in our ages, we were all three the best of friends, brought together by our common interest in music. Ian played in various concerts and was an excellent cellist.

I greeted him warmly, for I was very fond of him, and before showing him the music, made him feel quite at home. But Arnold had probably put him on his mettle, for almost at once, he asked me what this blessed trio was about, and why we were so eager to play it, and why we made such mysteries about it?

‘Arnold told me it was beautiful and awful all at the same time, and quite a difficult piece even from my point of view, which I presume must be taken as a compliment. I don’t mind admitting I’m keen to play it.’

Arnold grunted his disapproval from behind the thick clay pipe he always smoked, and I felt a guilty qualm in my mind that for some reason made me hesitate. As Ian looked a little surprised, I overcame my reluctance and, taking up the old manuscript, handed it to him. He looked at it carefully for several minutes without uttering a word, then he handed back the piano and violin parts, keeping the cello part, and remarked, ‘It ought to be deuced good, you know. Yes, that is quite a find you’ve made there, Greville, quite a find. But what an unpleasant little picture that is at the top. It is quite out of keeping with the music, I’ve a feeling.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ Arnold murmured. ‘I can’t say I agree.’

Ian looked up in some surprise, and I, sensing some embarrassing question concerning the music, rose to my feet and said, ‘Well, since we are all ready, there’s no sense in wasting time talking. Let’s get to work.’

There was little time wasted in preparing our instruments. Ian was eager and in some excitement; I was, for some strange reason, peculiarly nervous; Arnold, I noticed with a little irritation, was moody, and placed himself at the piano with a good deal of ill grace. Why did he accept to play his part so grudgingly, I wondered as I tuned my fiddle. After all, this was just a piece of music like any other. In fact, it was more beautiful than many I had heard and played. Surely his musician’s enthusiasm would be fired at being given such scope to express itself! For this trio, in its way, was a masterpiece.

I ran a scale and looked at the little man; the name Paymon in that neat, precise hand danced before my eyes and made me blink. I would have to stop my eyes wandering to the picture if I wanted to play my part properly. But wherever I looked, the man on his dromedary seemed to follow me and leer at my futile efforts to evade him. I glanced at Ian and noticed that he was looking a little annoyed.

‘This damn little picture is blurring my eyes,’ he complained rather crossly. ‘It seems to be everywhere!’

‘I noticed that myself,’ I admitted.

‘I can’t get it out of the way: the best thing to do is to cover it up.’

I gave them a small sheet of paper each and we all three pinned the sheets down upon our respective pictures. I felt a certain amount of relief at not seeing that ugly face and, tapping my stand with my fiddle bow, said, ‘Are you fellows ready?’

Two silent nods, and we began.

And now, how can I describe what happened, or how it happened? It is fixed in my mind and yet I cannot find words suitable to impart to you the horror of our experience. I think the music was the worst part of it all. As we played, I could hardly believe that this . . . this hellish sound was really being created by our own fingers. Hellish. Demonic. Those are the only words for it, and yet in itself, it was none of those things. But there was something about it that conveyed that ghastly impression, as though the author had composed it with the wish to convey profane emotions to its executants. I confess that I was frightened – really and truly afraid – possessed of such fear as I have never experienced before or since: fear of something awful and all-powerful which I did not understand. I played on, struggling to drop my fiddle and stop, but compelled by some force to continue.

And then, when we were half-way through, a strangled cry from Ian broke the horrible spell. ‘Oh God, stop it, stop it! This is awful!’

I seemed to wake as from a dream. I lowered my violin and looked at the young man. He was white and trembling, with dilated eyes staring at the music before him. He looked, with his thin face and yellow hair, like a corpse.

I murmured hoarsely, ‘Ian, what is the matter?’

He did not answer me. With one hand, he still held his cello; with the other – the right one – he made a sign of the cross and murmured, ‘Christ – oh, Christ, have mercy on us!’ and sank in a dead faint onto the carpet.

In two seconds, galvanised into action, we were beside him and, Arnold supporting his head and shoulders, I administered what aid I could to him, though my intense excitement made me of little use. He was very far gone, and it took us nearly twenty minutes to revive him. When he opened his eyes, he looked at us both, a prey to abject terror, then, clutching at my coat in fear, he murmured, ‘The music . . . the music . . . it’s possessed. You must destroy it at once!’

We exchanged glances, Arnold and I. Arnold seemed to say ‘I told you so’ and I accepted the rebuke. But I obeyed. This music was evil and had to be destroyed. I rose to my feet and went to the music stand. Then I suddenly felt the blood draining from my face and leaving my lips dry. For the music lay on the carpet – clawed to pieces. Only the grinning man on his dromedary was intact . . .

It was some weeks later, when we had somewhat recovered from our experience, that I ventured to open the book I had recently bought and which had been the cause of so much trouble. I had the name Paymon on the brain, and quite by chance, I opened the Infernal Dictionary at the letter P. I had no intention of looking for the name Paymon. I did not, of course, think it existed in any dictionary. I merely turned the pages over and looked at the illustrations. At the sixth or seventh page of that letter, my attention was attracted by the only picture in the column – that of a hideous little man, seated on the back of a dromedary. The name Paymon was written beneath it, along with a small article, concerning the illustration.

I read avidly. ‘Paymon: one of the gods of Hell. Appears to exorcists in the shape of a man seated on the back of a dromedary. May be summoned by libations or human sacrifices. Is very partial to music.’

adam o’riordan

A Thunderstorm in Santa Monica

Harvey was sitting