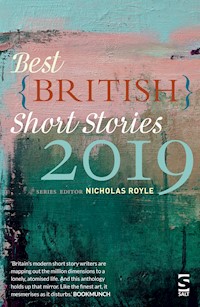

Best British Short Stories 2019 E-Book

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The nation's favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its ninth year. Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor's brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

BEST BRITISH SHORT STORIES 2019

edited by

NICHOLAS ROYLE

SYNOPSIS

The nation’s favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its ninth year.

Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor’s brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume.

Featuring stories by: Julia Armfield, Elizabeth Baines, Naomi Booth, Kieran Devaney, Vicky Grut, Nigel Humphreys, Sally Jubb, Lucie McKnight Hardy, Robert Mason, Ann Quin, Sam Thompson, Melissa Wan and Ren Watson.

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS WORK

‘Salt’s ‘Best British’ series reflects who we are; the state we are in. Britain’s modern short story writers are mapping out the million dimensions to a lonely, atomised life. And this anthology holds up that mirror. Like the finest art, it mesmerises as it disturbs.’ —TAMIM SADIKALI,Bookmunch

‘For those wishing to dip their toes into short stories currently available in a variety of mediums this collection offers an excellent primer. As a fan of the literary format I found it a well curated and enjoyable read.’ —Neverimitate

‘This annual feast satisfies again. Time and again, in Royle’s crafty editorial hands, closely observed normality yields (as Nikesh Shukla’s spear-fisher grasps) to the things we ‘cannot control’.’ —BOYD TONKIN,The Independent

‘For those new to short stories, the quality and breadth of what is being showcased here, will not easily be bettered. Moreover, the experiential difference that contemporary short stories offer, when compared to novel reading – the unique register they can strike – makes this collection all the more valuable.’ —Bookmunch

‘Nicholas Lezard’s paperback choice: Hilary Mantel’s fantasia about the assassination of Margaret Thatcher leads this year’s collection of familiar and lesser known writers.’ —Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian

‘Another effective and well-rounded short story anthology from Salt – keep up the good work, we say!’ —SARAH-CLARE CONLON,Bookmunch

‘It’s so good that it’s hard to believe that there was no equivalent during the 17 years since Giles Gordon and David Hughes’s Best English Short Stories ceased publication in 1994. The first selection makes a very good beginning … Highly Recommended.’ —KATE SAUNDERS,The Times

‘When an anthology limits itself to a particular vintage, you hope it’s a good year. The Best British Short Stories 2014 from Salt Publishing presupposes a fierce selection process. Nicholas Royle is the author of more than 100 short stories himself, the editor of sixteen anthologies and the head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, which inspires a sense of confidence in his choices. He has whittled down this year’s crop to 20 pieces, which should enable everyone to find a favourite. Furthermore, his introduction points us towards magazines and small publishers producing the collections from which these pieces are chosen. If you like short stories but don’t know where to find them, this book is a gateway to wider reading.’ —LUCY JEYNES,Bare Fiction

Best British Short Stories 2019

NICHOLAS ROYLE has published three collections of short fiction: Mortality (Serpent’s Tail), short-listed for the inaugural Edge Hill Short Story Prize in 2007, Ornithology (Confingo Publishing), long-listed for the same prize in 2018, and The Dummy & Other Uncanny Stories (The Swan River Press). He is also the author of seven novels, most recently First Novel (Vintage), and a collaboration with artist David Gledhill, In Camera (Negative Press London). He has edited more than twenty anthologies, including eight earlier volumes of Best British Short Stories. Reader in Creative Writing at the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University and head judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, he also runs Nightjar Press, which in 2019 celebrates ten years of publishing original short stories as signed, limited-edition chapbooks.

By the same author

NOVELS

Counterparts

Saxophone Dreams

The Matter of the Heart

The Director’s Cut

Antwerp

Regicide

First Novel

NOVELLAS

The Appetite

The Enigma of Departure

SHORT STORIES

Mortality

In Camera(with David Gledhill)

Ornithology

The Dummy & Other Uncanny Stories

ANTHOLOGIES(as editor)

Darklands

Darklands 2

A Book of Two Halves

The Tiger Garden: A Book of Writers’ Dreams

The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories

The Ex Files: New Stories About Old Flames

The Agony & the Ecstasy: New Writing for the World Cup

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing

The Time Out Book of Paris Short Stories

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing Volume 2

The Time Out Book of London Short Stories Volume 2

Dreams Never End

’68: New Stories From Children of the Revolution

The Best British Short Stories 2011

Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds

The Best British Short Stories 2012

The Best British Short Stories 2013

The Best British Short Stories 2014

Best British Short Stories 2015

Best British Short Stories 2016

Best British Short Stories 2017

Best British Short Stories 2018

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Selection and introduction © Nicholas Royle, 2019

Individual contributions © the contributors, 2019

The right ofNicholas Royleto be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2019

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-186-4 electronic

In memory of Dennis Etchison (1943–2019)

Contents

Introduction

The Husband and the Wife Go to the Seaside

Cuts

The Arrangement

The Heights of Sleep

Nude and Seascape

Beyond Dead

Toxic

A Hair Clasp

Reality

On the Way to the Church

Cluster

Smack

Curtilage

Kiss

Badgerface

On Day 21

Optics

A Gift of Tongues

Sitcom

New Dawn Fades

Contributors’ Biographies

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Nicholas Royle

If I hadapound for every time over the last year someone has remarked to me that the short story is enjoying a notable renaissance, I’d have enough money to submit numerous stories toAmbitand the Fiction Desk. But more on that later.

First, the New Statesman. I like the New Statesman – I subscribe to it and look forward to its arrival in my letterbox every Friday – but I wish it would do more for the short story. Among US newsstand magazines, Harper’s Magazine and the New Yorker regularly publish short stories. (Indeed, the New Yorker published a very good story, ‘Cecilia Awakened’, by Tessa Hadley, in Sepember 2018.) The New Statesman does, too, but regularly only in the sense of two or three times a year. The 2017–18 Christmas special featured an extract from a forthcoming new collection by Rose Tremain and the 2018 summer special extracted a story from Helen Dunmore’s final collection, Girl, Balancing & Other Stories (Hutchinson). The 2018–19 Christmas special giftwrapped us a new story by Kate Atkinson. How about a new story every week instead of just in the summer and at Christmas (and sometimes in spring)? That way we would get to enjoy not only more stories, but more new stories, rather than mostly extracts from forthcoming collections (rather a lazy way to publish short stories).

Short story competition anthologies have clearly become a bit of a thing. The Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology has reached volume 11; the Bath Short Story Award Anthology has been going since 2013 (in print form since 2014). The City of Stories anthology is on its second incarnation; it has a tag line – ‘Celebrating London’s writers, readers and libraries’. Spread the Word are responsible for it and this edition features over 60 London-based writers who took part in creative writing workshops in June 2018 in libraries across the city. A competition for 500-word stories was judged by four writers-in-residence – Gary Budden, Meena Kandasamy, Olumide Popoola and Leone Ross – who have all contributed pieces that appear alongside the winning stories.

May You: The Walter Swan Prize Anthology, edited by S. J. Bradley, is published by Scarborough’s Valley Press in association with the Northern Short Story Festival, Leeds Big Bookend Festival and the Walter Swan Trust. Bradley presents nineteen of the best from a field of more than 300 entries, including a short-list of six and three winners. The judges, Anna Chilvers and Angela Readman, awarded first and second prizes to Sarah Brooks and Andrea Brittan respectively, and they’re very good stories, but I would have been tempted to give top spot to P. V. Wolseley just for the description of a hamster – ‘He was golden-brown and sagged like a beanbag’ – in her story ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’. Megan Taylor’s ‘Touched’, short-listed, was also among my favourites.

Megan Taylor also appeared among last year’s chapbooks from TSS Publishing, with ‘Waiting For the Rat’, a worthy addition to an always-enjoyable sub-genre, holiday-let horror stories. It was the fifth in TSS’s series and it was followed by Christopher M. Drew’s very powerful ‘Remnants’, which reminded me of Cormac McCarthy, in a good way. I was delighted to see Rough Trade get in on the chapbook boom with Rough Trade Editions. Mostly non-fiction, the series has included one short story, ‘The Faithful Look Away’, by poet Melissa Lee-Houghton; I hope it goes on to feature more stories.

In yet more chapbook news, Word Factory and Guillemot Press formed a collaboration, the Guillemot Factory, to publish, in the first instance, four new stories in chapbook format. Lavishly illustrated, the four titles, by Jessie Greengrass, Carys Davies, Adam Marek and David Constantine, were received with great enthusiasm. In Constantine’s ‘What We Are Now’, my favourite of the four, an unhappily married woman bumps into an old flame. Nightjar Press, meanwhile, if I may mention my own baby, although now ten years old, published four more chapbooks, two in the spring and two in the autumn.

From single stories to single-author collections. Vicky Grut’s Live Show, Drink Included (Holland Park Press) is a selection of her published stories from the past twenty-five years. There are a couple of previously unpublished stories and two that appeared for the first time in other publications during 2018. My favourite of these was ‘On the Way to the Church’. I would have chosen it for this volume even if it hadn’t featured my favourite track on my favourite album by my favourite solo artist.

Other interesting collections included Sean O’Brien’s Quartier Perdu (Comma Press), Vesna Main’s Temptation: A User’s Guide (Salt) and the publishing phenomenon that was Ann Quin’s The Unmapped Country (And Other Stories). To say that the latter was ‘edited and introduced’ by Jennifer Hodgson, as is recorded on the title page, I’m sure gives very little idea of the amount of love, dedication and sheer hard work that must have gone into creating this book of ‘stories and fragments’ by the great British writer who died in 1973 at the age of 37. Hats off to Hodgson and to her publisher.

Is it a book? Is it a magazine? From issue ten of The Lonely Crowd the answer was on the cover: ‘the magazine of new fiction and poetry’. It still looks like a book, like quite a chunky anthology, and it’s still publishing tons of really good stories. In issue nine I particularly liked Courttia Newland’s ‘A Gift For Abidah’ and James Clarke’s ‘Waddington’, while stories by Kate Hamer, Jane Fraser, Lucie McKnight Hardy and Neil Campbell were the highlights, for me, in issue ten.

Newsprint is not dead: two new publications launched last year. Firstly, the Brixton Review of Books, an excellent and very welcome free literary quarterly created by Michael Caines, whose day job is at the TLS. Well, free if you happen to be wandering around south London when a new issue hits the streets (it’s given away outside tube stations, I believe, and I’ve seen it in the Herne Hill Oxfam Bookshop), or you can pay £10 for a subscription (check the web site). It features reviews, articles and columns, and, in issue three there was a notable story of ‘formless dread’, ‘Down the Line’ by Richard Lea. What’s not to like about formless dread? More, please. Secondly, at the Dublin Ghost Story Festival in June last year I picked up a copy of Infra-Noir, edited by Jonathan Wood and Alcebiades Diniz and published by Jonas Ploeger’s specialist press Zagava. The first issue contains stories by Brian Howell, previously featured in this series, and poet Nigel Humphreys, whose first-published short story ‘Beyond Dead’ is reprinted in the current volume.

Staying with literary magazines, the most interesting things in Hotel issue four – and they were very interesting – were either not short stories or not by British authors. In Structo issue 18, I was struck by Paul McQuade’s ‘The Wound in the Air’ and was similarly drawn to his not-unrelated story, ‘A Gift of Tongues’, in Confingo issue ten, which also included notable stories by a number of writers including Simon Kinch and Giselle Leeb. Jumping back to spring 2018, Confingo issue nine was packed with good stories. Stand-outs: Charles Wilkinson’s ‘Berkmann’s Anti-novel’, one of those stories about oddball school friends and how they turn out, which are always interesting, especially when they’re this well written; Elizabeth Baines’ ‘The Next Stop Will Be Didsbury Village’, which is best read on a Manchester Metrolink tram leaving either East Didsbury or Burton Road in the direction of Didsbury Village; David Gaffney’s ‘The Dog’, which, like Baines’ story, was written to be performed in the Didsbury Arts Festival. ‘Performed’ in this context may strike you as an overstatement, when such performance generally takes the form of reading the story to an audience, but Baines and Gaffney (if that doesn’t sound like a new ITV cop show partnership, I don’t know what does) always read well.

Lighthouse continues to illuminate the darkness with excellent writing. ‘One Art’, by C. D. Rose, in issue 16, was very good, but ‘Smack’ by Julia Armfield in the same issue was outstanding, probably the best story to appear in the journal during 2018. I don’t know what the jellyfish represent, but I don’t care. And yet I do care about the story.

The same dimensions and format as both Lighthouse and Confingo, Doppelgänger was a new publication edited by James Hodgson. Its web site states that it aimed to publish twice a year, with six stories in each issue, three realist stories and three magical realist stories. As far as I can tell, there has been no follow-up to the first issue, dated winter/spring 2018 and featuring work by Dan Powell, Andrew Hook, Cath Barton and others. Max Dunbar takes a risk with his story, ‘The Bad Writing School’. If you’re going to satirise the teaching of creative writing, you’ve got to be pretty sure of your ability.

If I had to pick a favourite story out of all those published in horror magazine Black Static during 2018, it would be Giselle Leeb’s ‘Everybody Knows That Place’, set on a camp site, which immediately makes it pretty horrifying for me. Some people find taxidermy horrifying, whereas I’m drawn to it, and that’s one reason why I liked Sally Jubb’s ‘The Arrangement’ so much. It appears in issue 42 of Brittle Star alongside other stories, Ren Watson’s ‘Sky-sions’ (reprinted in the current volume, under another title) and Josie Turner’s ‘The Guide’, that emerged as winners in the Brittle Star short fiction competition.

A friend alerted me to the fact that Ambit, the great avant-garde arts magazine founded by novelist and consultant paediatrician Martin Bax in 1959, had recently started charging for submissions. To submit a short story used to cost nothing, unless you counted the cost of photocopying, stationery and postage (not forgetting the stamped addressed envelope); now it costs £2.50, which Ambit says is to pay for the cost of using Submittable, a service that charges Ambit a monthly fee. There are advantages to Ambit in using Submittable, editor Briony Bax tells me: it enables their editors to work wherever they are; they can respond to submissions in a timely manner; it creates a virtual office for their eight editorial readers for whom an actual office would be prohibitively expensive etc. All reasonable arguments, of course, and Bax emphasises that there is a student/unwaged category with no proof required of such status, or people may still submit by post for free.

I don’t much like this development, even as Ambit celebrates its sixtieth birthday, but I haven’t let it stop me selecting two stories from last year’s issues of the magazine: Stephen Sharp’s ‘Cuts’ from Ambit 231 (in the same issue I also liked John Saul’s ‘Tracks’) and Adam Welch’s ‘Toxic’ from Ambit 232.

Ambit is not alone. Magazines such as Ploughshares and Glimmer Train in the US have been doing it for years, and, as Rory Kinnear says as Stephen Lyons in Russell T. Davies’s post-Brexit drama Years and Years, ‘We are American. Our business is American, our culture is American. We’re certainly not European, are we?’

Also doing it is the Fiction Desk, whose £3 fee can be avoided if instead you buy one of their anthologies, the latest of which, their twelfth, is And Nothing Remains. I may not like submission charges, but that’s not contributor Alex Clark’s fault and so I will say I enjoyed her story ‘Briar Rose’, as I did her story ‘The Thief’ in Stroud Short Stories Volume 2 (Stroud Short Stories) edited by John Holland. This second volume in the series features stories read by their Gloucester-based authors at Stroud Short Stories events between 2015 and 2018. In particular I enjoyed Joanna Campbell’s ‘The Journey to Everywhere’, its exuberance of language and character reminding me of the great William Sansom.

There was no shortage of anthologies published last year, among them Unthology 10 (Unthank Books) edited by Ashley Stokes and Robin Jones – congratulations to them on reaching that milestone. The blurb on the back of Tales From the Shadow Booth Vol 2 edited by Dan Coxon describes the Shadow Booth as a ‘journal of weird and eerie fiction’, taking its inspiration from Thomas Ligotti and Robert Aickman, but nothing in it reminded me of either writer. It feels more reminiscent of The Pan Book of Horror Stories, and, speaking as someone whose first short story sale was to that long-running series, I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. Mark Morris, a contributor to the Shadow Booth, is the editor of New Fears 2 (Titan Books). In his introduction he acknowledges the lasting influence of un-themed horror anthologies, such as the Pan series and others. He goes on: ‘My aim with New Fears, therefore, is to bring back the un-themed horror anthology – and not as a one-off, but as an annual publication, with each volume acting as a showcase for the very best and most innovative fiction that this exhilarating genre has to offer.’ What a shame, then, that publishers Titan pulled the plug after this second volume, in which a highlight for me was Stephen Volk’s stomach-churning ‘The Airport Gorilla’, which may be narrated by a soft toy, but is extremely hard hitting.

Jez Noond’s ‘Zolitude’ drew my eye in The Cinnamon Review of Short Fiction (Cinnamon Press) edited by Adam Craig. I liked it, even if I didn’t really understand it. I sense strongly that the lack is within me and not the story. I always enjoy Courttia Newland’s stories; ‘Link’, in Everyday People – The Color of Life (Atria Books) edited by Jennifer Baker, was no exception. Ramsey Campbell led from the front in The Alchemy Press Book of Horrors (The Alchemy Press) edited by Peter Coleborn and Jan Edwards; Campbell’s ‘Some Kind of a Laugh’ is followed by a further 24 stories by a roll-call of horror writers. Standing out among the stories in Dark Lane Anthology Volume 7 (Dark Lane Books) edited by Tim Jeffreys is ‘Your Neighbour’s Packages’ by Megan Taylor, which you read with a dynamic response of mingled horror and delight, as the neighbour’s packages mount up in the protagonist’s home. You hope the packages remain unopened while the story delivers on its promise. You’re not disappointed. It’s followed by Charles Wilkinson’s ‘Time Out in December’, which could hae been called ‘Hotel Lazarus’ and could have been written by Franz Kafka.

Running a small press is a draining business in lots of ways, not least financially. Manchester’s Dostoyevsky Wannabe don’t charge a submission fee, but nor do they supply their writers with contributors’ copies. This didn’t put off the writers contributing to Manchester edited by Thom Cuell, among them Sarah-Clare Conlon and Anthony Trevelyan, whose stories, ‘Flight Path’ and ‘Repossession’, respectively, were my favourites. While I can’t help feeling that, if you’re not paying your writers, providing them with a free copy of their work is the very least you can do (co-founder Richard Brammer puts forward a case for it being more punk operation than big corporation), I love the look of Dostoyevsky Wannabe’s rapidly growing list of publications, for which credit must go to art director Victoria Brown.

Let’s stick with the north for two more anthologies published last year. Firstly, Bluemoose Books published Seaside Special: Postcards From the Edge edited by Jenn Ashworth, whose prompt for stories inspired by the coast of the north-west of England, produced a fascinating anthology with some outstanding stories. Melissa Wan’s ‘The Husband and the Wife Go to the Seaside’ is remarkable, mainly for its style and its embracing of doubt and uncertainty. Pete Kalu’s historical piece on the subject of slavery is impressive, partly for the unflinching examination of its subject matter and partly for its original approach, the story taking the form of a will being dictated. Also notable were Andrew Michael Hurley’s ‘Katy’, a missing-child story with a difference, and Carys Bray’s haunting tale about the song of the Birkdale Nightingale, or Natterjack toad.

Secondly, and finally, there was We Were Strangers: Stories Inspired by Unknown Pleasures (Confingo Publishing) edited by Richard V Hirst. It so happened that my favourite story in this anthology of stories inspired by Joy Division’s first album was Sophie Mackintosh’s ‘New Dawn Fades’, which also happens to be my favourite track off the album. Other highlights, for me, included David Gaffney’s ‘Insight’, Zoe Lambert’s ‘She’s Lost Control’ and Jessie Greengrass’s ‘Candidate’.

There were more stories in more magazines, anthologies and collections, as well as on web sites and broadcast on radio. I can’t claim to have read them all, but I have read as widely as I can and selected what I think are the best. Next year’s volume will be my tenth – and last – as editor of this series.

NICHOLAS ROYLE

Manchester

May 2019

The Husband and the Wife Go to the Seaside

MELISSA WAN

The husband andthe wife arrived at their cottage on the coast one moonless night. Both were ready for a change and told themselves this time away was the beginning. From a distance they saw that their cottage, mid-terraced in a row of holiday homes, was the only one with its lights still on, shining into the dark. The wife said it looked exactly like the pictures and when the husband stepped from the car to unlock the gate, she smiled at him as he turned back, before realising he wouldn’t see her in the glare of headlights.

Approaching a house with all the lights on made the wife feel like an intruder, but the husband turned the key and edged her in with his hand on the small of her back. Everything awaiting them seemed exactly as they expected.

‘Nice of them to leave the heating on,’ said the husband, peering into the dining room. The wife walked upstairs, half expecting to come upon another couple in their bed, but instead the towels and blankets were neatly folded, not a crease in sight. Downstairs, the husband had left a trail into the sitting room, his brogues kicked off, suitcases abandoned in the hallway. He was flopped into an armchair – the best one, she noticed – and tapping into his phone.

‘After this we’re turning them off,’ he said, ‘and I’ll find a place to hide them.’

‘Do we have to?’ asked the wife. ‘What if I need to get in touch with you?’

The husband looked up with raised eyebrows. ‘You said we needed some time away, so that’s what we’re doing. It’s two weeks.’

The wife nodded and turned into the kitchen. She found a gift basket on the counter with a handwritten card reading Welcome to Arnside.

‘We can always eat these,’ she said, holding up a tin of spaghetti hoops.

‘What an odd thing to leave in a hamper,’ said the husband.

‘They’re nostalgic. We used to have the alphabet ones. I’d eat them from my bowl which had the alphabet around the side.’

‘That’s cute,’ said the husband.

The wife told him she could heat them up.

‘No thank you.’ He fished out a packet of shortbread and sat down at the dining table. ‘We never ate anything tinned.’

The wife put the hoops back into the basket and sat across the table from the husband. She kept mistaking the tap of a twig on their kitchen window for a knock at the door and every time she’d snap up her head. She could hear the husband chew above the thin vibration of the fridge.

‘It’s so quiet here,’ she said.

‘That,’ said the husband, ‘is the sound of having left it all behind.’

The wife turned on the television, glad for the false laughter of a studio audience, and asked if they could go to the chip shop tomorrow. The husband said she could do what she wanted.

‘It’s what I’ve been dreaming about,’ said the wife. ‘The drip of all that chip fat.’

The husband unfolded his paper and raised it to hide his face. On the cover, the wife read the headline: Body Found in River Bela. The photograph was of the river, static in black-and-white, and didn’t show the corpse. They’d crossed the river on their drive through Milnthorpe, had stopped to walk over the footbridge, and the wife’s eyes widened at the thought of a corpse drifting cold and stiff below their feet.

‘What’s that noise?’ she asked, looking up at the black window.

‘What noise, darling?’

‘It sounds like breathing.’

The husband told her not to let her imagination run away with her, and turning up the volume, the wife stared blankly at the screen as the husband turned the page.

When the wife got into bed, she left her light on for longer than usual. Her eyes would lose their place in her book, find it again and read the same sentence over. She wore her new satin nightclothes spotted with pink roses and slipped herself between the sheets. When the husband came in wearing his flannels, he kissed her on the head, switched off his light and turned away onto his side.

‘“It was times like these,”’ the wife read, ‘“when I thought my father, who hated guns and had never been to any wars, was the bravest man who ever lived.”’ She turned to look at the back of the husband’s head; she could detect where his hair was beginning to thin. She closed her paperback, sipped at her water and turned off her reading lamp.

‘Goodnight,’ she said.

The husband made a noise with his throat.

‘It’ll be nice to be here, won’t it?’ she said. ‘To refresh.’

The wife adjusted her pyjamas until an audible sigh came from the husband’s side and she was still. There was a skylight in the ceiling through which, on her back, she watched the drift of cloud.

In the morning the husband and the wife were woken by the sound of drills. A team of builders were busy on scaffolding around the front of the house next door.

The husband retrieved his phone to email the cottage owner, who wrote back to tell them it had been on the website. Indeed, he found the small print: ‘From mid August until January there will be building work next door. Some noise and disruption may be experienced.’

‘You mean it’s going to be this loud the whole time?’ asked the wife.

The husband said they would be out most days anyway, and told her not to look when he put the phone away.

In daylight the house looked tired, its walls and surfaces more grey than white. On the website the sitting room had been described as historic, but the bookcase was stuffed with second-hand romance novels and the wife knew the throws were bought in Ikea.

‘It could do with a lick of paint,’ she said, to which the husband replied that this was what they called shabby chic, that it was a style.

The wife boiled the kettle and took her cup of tea upstairs. Since the husband had claimed the armchair, she contented herself either with the sofa in the sitting room or this chair with the view. She sat by the window and looked down onto the street beyond their front garden, from where she could see the labourers moving back and forth. She watched, trying to ignore the noise, and when the bronzed arms of a worker caught her eye her cup stopped before her lips. His muscles shifted as he hoisted a plank onto his shoulder and he walked with extraordinary confidence for somebody so high up. When he lifted the board, she glimpsed the dark growth of hair beneath his arms.

After breakfast, through which the drills whined and the wife overcooked the eggs, she left the house arm in arm with the husband. The promenade was a few hundred metres away, a mixture of express supermarkets, small-town cafes and upscale boutiques; to walk from the pub on one end to the chip shop on the other took about five minutes. This morning the sky was turned white by a layer of cloud, and as they passed groups of elderly ramblers in fleeces and walking boots, the husband greeted them as though he knew them, shaking their hands because it was a small town, and as he said, things are done differently in small towns. The wife smiled but kept her eyes squinted on the mudflats, her legs trembling as gusts of wind blew up her skirt. Luckily she’d packed a jumper but eventually she had to ask the husband if she could buy a pair of trousers from the shop.

‘I did tell you,’ he said, handing her their credit card.

The husband waited in the pub, sitting down with a pint as the wife closed the changing room door. It was a shop for ramblers and the wife looked so ridiculous in the waterproof pants and sandals that she reluctantly bought a pair of their cheapest walking boots and asked to wear both immediately.

She read on the handwritten labels that the fleeces were made from a flock of rare Woodland sheep, farmed only a few metres away. This and the antiquated tin of Werther’s Originals on the counter made the wife think it might all be staged, as though if she opened a wrapper she would find a piece of folded card inside.

‘You know there are rambling groups here,’ said the shopkeeper. ‘And Cedric does cross-bay walks. They’re very popular.’

The wife took her receipt, saying thank you but she wasn’t a big walker.