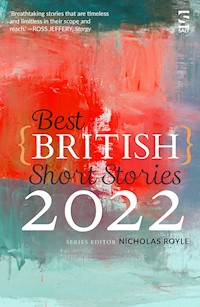

Best British Short Stories 2022 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The nation's favourite annual guide to the short story, now in its twelfth year. Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or, more accurately, by its title. This critically acclaimed series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere. The editor's brief is wide ranging, covering anthologies, collections, magazines, newspapers and web sites, looking for the best of the bunch to reprint all in one volume.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

CONTENTS

vii

To the memory of Uschi Gatward (1972–2021)

viii

NICHOLAS ROYLE

INTRODUCTION

‘… good short stories are notoriously hard to write, harder perhaps than novels, and mediocre stories lie thick on the ground.’ Wise words. Who wrote them?

This introduction usually conducts a brief survey of short story publishing in the UK. I asked the publisher if I could do something different this year. I could, for instance, knock something up out of excerpts from my fan mail, as one bestselling writer did in the introduction to a collection spun off from one of his novels, but I have neither the personality type nor the postbag. I wondered if anyone had ever published a blank introduction, either by mistake or Oulipian design. Instead, let’s mark the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Picador. From my collection – around a thousand titles published between 1972 and 2000, when they dropped the white spine/black type – I picked out collections and anthologies. Could I come up with a top ten to take to a desert island?

Among their first eight titles were Jorge Luis Borges’s A Personal Anthology and The Naked i edited by Frederick R Karl and Leo Hamalian. Among the stories, the Borges also contains poems and The Naked i sneaks in three novel extracts, and both include pieces of non-fiction. The Naked i – one of two Picador anthologies edited by Karl and Hamalian, the other being The Existential Imagination – contains stories by Carlos Fuentes, Sylvia Plath, Richard Wright and Borges, which meant the Argentine featured in two of the launch titles, but I’ll go for his other Picador collection, The Aleph and Other Stories, where – poets, look away now – you’re not in danger of running into any poetry. There’s no poetry in The World of the Short Story edited by Clifton Fadiman, just 850 pages of some of the best short fiction of the twentieth century. It’s hard not to pack it, despite its bulk.

I’ve got a knee-high pile of Picador books of erotic prose, modern Indian literature, contemporary Irish/Scottish/New Zealand fiction, as well as Raymond Van Over’s A Chinese Anthology and George Lamming’s Cannon Shot and Glass Beads: Modern Black Writing and Joachim Neugroschel’s Great Works of Jewish Fantasy, and these are all superb, but they fall back on including a number of novel extracts. If there’s one thing worse than poetry, it’s the novel extract. What is it good for? Absolutely nothing. Alberto Manguel keeps his extracts to a minimum in his wonderful Black Water: The Anthology of Fantastic Literature and I don’t think there are any in subsequent volumes Other Fires: Stories From the Women of Latin America and White Fire: Further Fantastic Literature. I so wanted to pick The New Gothic edited by Patrick McGrath and Bradford Morrow, but five of its twenty-one pieces are – sorry to keep going on about this – extracts and you only find this out when you reach the end of each one.

The Picador Book of Contemporary American Stories edited by Tobias Wolff contains stories by writers who also have collections in Picador such as Scott Bradfield, Raymond Carver, Andre Dubus, Mary Gaitskill and Robert Stone. Wolff, who doesn’t pick himself for the anthology, also has a collection. Other American writers with Picador collections include Harold Brodkey, Rebecca Brown, Robert Coover, EL Doctorow, Jennifer Egan, F Scott FitzGerald, MJ Fitzgerald, Ellen Gilchrist, Jamaica Kincaid, Ring Lardner, Antonya Nelson, Thomas Pynchon, Damon Runyon, James Salter and Bob Shacochis. Long lists of names. Not very interesting, I know, but I don’t want to miss anyone out. Some of those collections contain stand-outs, such as ‘The Foreign Legation’ in Doctorow’s The Lives of the Poets, ‘The Babysitter’ in Coover’s Pricksongs & Descants, while others are consistently excellent, like The Stories of Raymond Carver.

Ellen Gilchrist’s In the Land of Dreamy Dreams, Andrew Williams’ cover recalling Magritte’s The Reckless Sleeper, is a powerful collection of stories from the American South. Endings that take your breath away, even when – especially when – you see them coming. MJ Fitzgerald’s Rope Dancer opens with ‘Creases’, about a man who folds up his girlfriend up and puts her in a box. ‘The Fire Eater’ is a brilliant metafictional commentary on how to write a story. Fitzgerald recently retired after three decades’ teaching writing. ‘My job was to carry the bag,’ writes the narrator of Rebecca Brown’s ‘What I Did’ in The Terrible Girls. She makes you both want to know and not want to know what’s in the bag.

Other international writers: Tim Winton, Gabriel García Márquez, Bruno Schulz, Idries Shah and Italo Calvino, whose short stories I know I should find more exhilarating than I do, but he’s not the only widely acknowledged genius I struggle with. Dare I admit that Angela Carter, whose Black Venus was a Picador, is another? Samuel Beckett – another, but is More Pricks Than Kicks a novel or a collection? Picador called it his first novel. Other Irish writers with undisputed, very fine Picador collections: Desmond Hogan and Bridget O’Connor.

There are relatively few British writers with collections boasting that distinctive white spine. Julian Barnes is one – you might enjoy Cross Channel on the Eurostar – and Alan Beard is another. The unsentimental but affecting way Beard writes about ordinary people in Taking Doreen Out of the Sky makes him irresistible. I remember falling for Ian McEwan’s First Love Last Rights and In Between the Sheets. I reread both and found I’d lost that loving feeling, with one or two exceptions (‘Solid Geometry’, ‘Last Day of Summer’). Nor will I take The Best of Saki, though I know I would enjoy dipping into it. I tried dipping back into Graham Swift’s Learning to Swim & Other Stories and liked it less than I had. Lack of space excludes Patricia Duncker’s Monsieur Shoushana’s Lemon Trees and Clive Sinclair’s collections.

In the end, Fadiman’s huge anthology edges out The Naked i, and Black Water gets in, because water always will. Wherever I open the Carver and read an opening line, I want to read on, so he’s in. Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles and Borges’s The Aleph both feel essential. Beard squeezes in to represent British writing, which has not done well. Jamaica Kincaid’s At the Bottom of the River is one of the shortest and best collections I’ve ever read. The opening lines of ‘Blackness’: ‘How soft is the blackness as it falls. It falls in silence and yet it is deafening, for no other sound except the blackness falling can be heard.’ Picador recently reissued it. Maybe, if they have the time/space/rights they’ll also reissue Gilchrist’s In the Land of Dreamy Dreams, Fitzgerald’s Rope Dancer and Brown’s The Terrible Girls, which complete my top ten.

The line quoted at the top? From Ian McEwan’s ‘Reflections of a Kept Ape’, which for forty years I thought was called ‘Reflections of a Kent Ape’.

MONA DASH

LET US LOOK ELSEWHERE

I imagine you come here with expectations. You want to hear tales of the sari, of the mango, of cow hooves kicking up a dry dust you will want to wipe off with a scented handkerchief. You want to hear of lavender, of turmeric, of jasmine soothing the hot summer evening in a distant tropical country. You expect to be told stories of a certain woman, a certain man, in a certain way. You want to feel, but nothing beyond the ordinary, nothing you cannot stomach along with a thick steak, the knife a tad bloody from the rare meat.

Prepare then to be annoyed. Prepare to shake your heads at the lack of clichés. Prepare to throw away the book even. Prepare to be angry that anyone can write these stories, it is no longer the right of the powerful, the strong, the erudite. Nowadays anyone can take up a pen, a laptop, and float words on the page, dipping into history and geography and creating; what we may not expect, tell a story not told before.

The stories I want to write may be nothing you expect or may be everything you desire. I can write about the place I am from, the shores I have arrived at, the people I have met. I can write about the accidents, the tragedies, the way humans lost breath when they didn’t expect to or were maimed and silenced. The blood which flowed when people attacked others, their homes, their bodies. Inspired by the books on war, I can, for example, write about gas chambers or the site where a nuclear bomb ripped the soil and its heart, or through the eyes of a little child whose parents kissed, and were shot before him.

I can fly across continents and write about modern wars, the one where planes drove into tall, proud towers, the ones which continue as delusional youth wield axes or guns or, strapping explosives on, aspire to explode and achieve heavendom, annihilating innocent people. Moved by the video of the civil war and watching neighbours bomb the Stari Most, I can explore strife in faraway countries. I can write about the betrayal and naivety which led to foreign countries ruling my own, but that too has been done; the red and blue flag has been replaced a million times by the tricolor, and evil is often equated with the colour of skin.

There is so much to write. Except that it has been written before, in ways fourscore and one, and I want to write something new, infinitely precious. So let me write some simple tales. Stories told in three days.

Day 1: the world will be made, love will be found, love will be had, and creatures sing, dance, collude, procreate, collate. Trees will grow so tall to never let anyone live without a roof on their heads. Crops will grow healthy and fruits will ripen and burst. Birds will sing timelessly. Lovers will never be jealous, and fathers will never be cruel, and children will never die. Words like harmony, beauty and happiness will take form.

Day 2: there will be more of the same, but snakes will hatch out of giant eggs, grow, mate and slowly slither into lives and loves. Monstrosities will take concrete form, and not wander nebulously as before. Atrocities will be committed and while there will be villains, heroes will stand tall. Our eyes will glisten over when we see men helping children, women helping older frail men, black, white, and brown singing together. We will remember humanity.

Day 3: the last day. Everything will fall. All the stories I have told before, all the words I have embellished into poetry, into songs, all the tunes I have hummed and taught others. Everything will perish. Whether from fire licking us, or water submerging our lungs, or the moist wet earth softly smothering us in her everlasting hugs. Everything will give way to nothing, to the completeness in a circle.

Will that be enough for you? Will it meet your expectations of a writer; a woman, a man, a criminal, a lover, an individual, a communist, a terrorist, a believer, a mother, a friend, a foreigner, a nationalist, or whoever else might need to take up the mantle of the pen? The scourge of the word for our senses to react? Or will there be more demands from you about the perfect story?

I wish I could write about women who are nourished physically and emotionally and spiritually so in return they can protect; of men who are so strong and gentle that they can give and give. Not of these wild-eyed bare-breasted hysterical women, caught between worlds, between emotions they do not know they have, and angry helpless men, not knowing, given to lawlessness and destruction. All of them caught between selves, between cities, between the past and the present, and searching. But whatever they find, it doesn’t seem enough, as if this is not it, this is not the answer. The answer is somewhere. If we explore further, if we travel somewhere else, outside of ourselves, if we look. Let us then look elsewhere, and somewhere, it will all come together.

But, wait, let me write. Allow me my writing.

SARA SHERWOOD

HOW YOU FIND YOURSELF

1. You decide, at thirteen, you like ‘bad boys done good’ because you overhear the phrase in a conversation between your mother and your Auntie Tina. That, and you have a crush on Jamie Mitchell off EastEnders. At your high school in Batley, the closest to this you can get is Stephen Dooley.

a. Stephen Dooley has a shaved head and a fake diamond stud in his right ear. He holds your hand at Bradford ice-skating rink one Saturday in November.

b. The same day, Stephen Dooley kisses you, your first kiss, with sloppy lips and a tongue which still tastes of bacon-flavoured crisps, at Bradford Interchange bus station.

c. As your relationship develops, one of your regular arguments becomes whether EastEnders or Coronation Street is the better soap.

d. You will, throughout university, work and beyond, have this argument with many other people. You will always gun for EastEnders.

2. Due to your notorious snogging sessions with Stephen Dooley in the Year 9 common area, you become irresistible to other boys in your year group. Most notably:

a. Mohammed Nassar in Year 10 (October to March).

i. The highlight of your relationship is when he fingers you on the sofa to the sounds of canned laughter in Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway when your mum is out at Auntie Tina’s.

b. Kieran Luther in Year 10 (March to July).

i. You go out with Kieran for four months until he kisses Aleena Ahmad at the end-of-term disco. From here, you will always associate Usher’s ‘Burn’ with the gut-punch of heartache.

c. Harry McDonald in Year 11 (September to June).

i. Harry McDonald is in Sixth Form.

ii. You get drunk for the first time with Harry McDonald.

iii. You lose your virginity to Harry McDonald at his brother’s flat in Huddersfield.

iv. You tell all your friends how romantic it was but all you remember is a dusty spider web which spanned from the ceiling to the naked light bulb.

3. At sixteen, you tell your friends that you have outgrown rough-talking boys; you now like boys who are into the Ramones, books by Jack Kerouac and vinyl records. This is mainly because you stumble across a repeat of The OC over the summer holiday and decide that you prefer Seth Cohen over Ryan Atwood.

a. Your school’s equivalent to Seth Cohen is Sohail Sheikh. He’s the older brother of your friend Khadijah Sheikh.

b. Sohail is at college in Leeds, but you see him at parties.

c. Sohail writes poems – funny poems – about TV and craving cigarettes during Ramadan.

d. You spend your two years of Sixth Form devoted to Sohail. You change your Myspace profile picture to something poutier and more filtered in black-and-white to get his attention.

e. It never works.

4. As part of your devotion to Sohail, you develop an all-encompassing crush on the host of Big Brother’s Big Mouth, Russell Brand.

a. You create a LiveJournal devoted to Russell Brand. You find pictures on the internet and use Paint to draw hearts around his backcombed hair.

b. You stumble across FanFiction.net. You write long messages to your fellow writers on the strengths and weaknesses of their stories which revolve around Russell’s madcap adventures through London with a female sidekick (with whom, of course, he eventually falls in love).

c. You develop friendships with these online girls. They’re much more interesting than your friends at school: they live in happy-sounding places like Guildford and Hereford.

d. Over the course of Year 12, you write a 90,000-word romantic comedy fanfiction in which Russell Brand is forced to pretend you are his girlfriend as part of an undercover operation.

i. You win Best Overall Fic at the online awards on LiveJournal.

ii. Your Head of Sixth Form says you cannot put this on your UCAS form.

5. When you finally kiss Sohail, at a Year 13s birthday party at Ackroyd Street Working Men’s Club in Morley, his tongue feels small in your mouth. You remember walking away from him, to the smirks of your friends, the soles of your shoes coming unstuck from the beer-stained floor.

a. Your crush melts and flutters into the air like confetti. You try to catch it. You force yourself in his bed, in your bed, in someone’s parents’ bed while a cruel house party rages on beyond the bedroom door, to like him – to want him – again.

b. You become his girlfriend.

c. You realise Sohail is deeply boring; you develop a furious dislike of the Beat poets and listen to Beyoncé loudly, obnoxiously and with joy.

d. Your breakup is triggered by an argument about the ethics of reading novels by William S. Burroughs.

i. He calls you inauthentic.

ii. You call him a knobhead.

e. You find comfort in assuming the identity of a grieving ex-girlfriend (you’ve been told you look pretty when you cry) but really you feel like a failure, like you’ve been scrubbed clean and found to be less than.

f. When Sohail leaves for university, you’re relieved, but you are unmoored without your hobby of the crush.

6. At university – York, where you study English Literature – you meet Jasmine. She has long blond hair and hardy thighs; she’s used to riding horses, sloshing through mud in Hunter wellies and eating her breakfast – porridge, with blueberries – in a flag-stoned Shropshire kitchen. You’re surrounded by girls like these on your course, in your halls, on the student newspaper, but Jasmine … Jasmine is magical.

a. You bond by watching Gossip Girl on ITV2.

i. Jasmine has blond hair which makes her the Serena van der Woodsen to your Blair Waldorf.

ii. You both agree that Chuck Bass, rather than Dan Humphrey, is the romantic lead of the series. This is mainly because of Chuck Bass’s hair which, unlike that of many of the boys in your seminars, is parted at the side and swept romantically across his forehead.

iii. The subject of your daydreams, which was previously a man in skinny jeans with riotous hair, morphs into a suave New York hotelier with a transatlantic accent and a bottomless bank account.

7. In your second year at York you meet Ben. You both review albums and books for the university newspaper. He’s from Sheffield, and his accent – harsh and deep – sends electric sparks down your spine and into your knickers. Ben likes Peep Show, coffee and Modest Mouse.

a. You quickly school yourself on all three. b. When he catches you scrolling through Oh No They Didn’t, your favourite celebrity gossip website, in the library he uses this as an example of your shallowness.

i. This becomes a running joke throughout your relationship.

8. You allow Ben to fuck you – and your heart – and mock your love of celebrity stories for two years.

a. In the run-up to your final exams, you walk out of a seven-hour stretch in the library to get a coffee and KitKat Chunky with Jasmine and see Ben kissing Charlotte, his housemate, outside a cafe on campus.

b. When he changes his Facebook status to ‘In a relationship’ two days after your final exam, you delete him from your Facebook and cry for three days.

c. On the night you get your final results (a First despite the fact you spent your exam worrying more about Ben than Patrick Hamilton), you text him a topless selfie from the pub toilets. He doesn’t respond.

9. You move back home and are unemployed. Batley has always been depressing, but now it’s even more so. You hate it. You wish you didn’t have the lazy vowels of the West Riding cursing your voice. You wish you were Jasmine, who is staying with her godparents in Barnet and has just scored her third unpaid internship at a fashion website.

a. You’re not jealous of Jasmine.

b. You direct you anger at your mother, who has kept you stuck in a two-bedroom terraced house on the outskirts of three useless cities.

c. You wish you had:

i. Rich godparents.

ii. A successful aunt.

iii. A cousin who works at The Telegraph.

10. In February, after months of endless applications, London beckons you with a graduate scheme at a multinational marketing firm which offers career progression and a pension, and you oblige.

a. You find a flat in Clapham on SpareRoom.

i. You choose Clapham because Jasmine’s brother lives there and he’s the only person you know who lives in London.

b. You gradually get rid of your New Look miniskirts and stained Primark knickers and, with your new money, buy minimal dresses and structured blazers from Whistles, Hobbs and Jaeger.

c. You tie your hair in a severe bun. At first it hurts; you feel like your hair is being twisted away from your scalp.

d. You attend a training session for women in leadership where you learn not to talk about what you watched on the TV last night or apologise for your mistakes.

e. You start saying things like ‘Why don’t you just find a better job?’ when your mum complains about her ongoing pay freeze.

i. You roll your eyes when she tries to explain that there aren’t any better jobs around there for her, and besides, she likes her friends at the school, likes the summer holidays, the pension. Why would she sacrifice that for a couple of pounds more at the end of the month?

11. You start to construct a narrative about yourself, about your past.

a. You were born into an ambitionless household.

b. You are the product of social mobility.

c. You try to scrub away all the automatic references your brain makes to EastEnders and Gossip Girl and Big Brother.

d. The new identity fits over you, like armour.

e. You do battle in it every day.

12. You’re twenty-five. You’re at a networking event in a bar in Canary Wharf and you meet Andrew. He’s tall. He’s handsome. He’s a perfect fit for you, the new and shiny you. Everyone says so.

a. At first you tell Jasmine that you think Andrew speaks like he’s got a cock in his mouth. Eventually you forget you ever said it.

b. You meet his friends, his parents, his granny – a woman so unlike your own chain-smoking Nana – in Winchester.

c. He comes to Batley to meet your mum.

i. He tells you that he’s never been in a house where you step straight off the pavement and into the living room.

13. When you’re six months into your relationship, you and Andrew go on a bank holiday trip to Whitstable.

a. You have oysters for the first time on the seafront.

b. Across the table, you run your fingers along his cheek and let his day-old stubble scratch under your fingernails. You can’t stop touching him. He can’t stop touching you.

c. Back at the hotel, you fill the deep, wide bath with Neal’s Yard bubble bath.

i. You both get it. He smiles across the bath at you, his two front teeth resting on his sea-salt lips.

ii. You tell him that when you were small you would fill the bath up to the top, clamp your legs together and wiggle about, pretending that you were a mermaid.

iii. You tell him how lonely you were as a child.

iv. With no brothers or sisters, you would read or watch the telly so your imagination could explode with stories to keep you company.

1. You were a lost princess trapped in a boarding school.

2. You were an orphan sent from India to live in Yorkshire.

3. You were a mermaid who longed to live on the land.

4. You were the secret daughter of spies.

5. You were a lion running away from the death of her father.

v. ‘I’ve never told anyone that,’ you say.

vi. ‘I love you,’ he says.

14. You and Andrew have been together for two years. You suspect something is wrong.

a. You only have sex once a month.

i. Once every three months.

b. He rolls away from you in bed.

c. He spends more time at the gym.

i. You suggest you go together – you normally go to Spin on a Saturday morning with Jasmine, but you’re desperate enough to forgo this to save Andrew.

ii. He bats the suggestion away with a scrunched-up mouth like a punch to the chest.

d. You try to resist but you end up going through his phone. You find what you’re looking for: flirty messages from a woman – Polly – who he works with.

i. Of course it would be a fucking Polly.

ii. You find her LinkedIn and feel smug when you find what you’re looking for: a nursery-to-Sixth Form private education in the south of England and a First Class BA (Hons) in Classical Civilisation from Christ Church, Oxford.

iii. Of course, Andrew would leave you for a Polly. Someone who wouldn’t need to be taught how to pronounce Diptyque and whose family also has a bolthole in Norfolk.

1. ‘What the fuck is a bolthole, anyway?’ you rage at Jasmine.

e. Days later, when you confront him, Andrew tells you it’s nothing, but he wishes that he didn’t feel so stifled by your relationship.

i. And, by extension, you.

ii. He suggests some time out.

iii. You suggest getting engaged.

15. You find a flat. You pack up your life (half a life, because who are you without him?) into boxes. You cry into the pillow on your first night in your new flat in Stoke Newington. Quietly, so your new flatmates – Sophia and Beth – don’t hear.

a. When you wake up on Saturday morning, you reach for him but there’s nobody there.

b. The bed smells of nothing.

c. Food tastes of nothing.

d. You are nothing.

i. Just another girl whose voice melted away into a regionless blur whose only true interests are Kylie Jenner’s Instagram Stories and the new series of Gilmore Girls on Netflix.

ii. You wish other people didn’t have so much when you feel like you have so little.

iii. Basic bitch.

iv. Working class.

v. Shallow cunt.

vi. Boy-obsessed.

vii. Stupid twat.

viii. Ex-girlfriend.

16. Time passes slowly.

a. You learn what loneliness is.

b. You stand in front of a Jackson Pollock painting and feel … nothing. It’s just red and black.

c. You sleep in the middle of the bed.

d. You give yourself to Netflix at the weekend.

e. You start watching EastEnders again because there’s nothing else to do in the evening.

f. You download Tinder.

g. You stare at the ceiling while a Durham-educated civil engineer, with a body like a mountain, fucks you.

i. He invites you to watch him play rugby and to meet his friends.

ii. You ghost him.

h. You learn that Sundays are the worst.

i. And bank holidays.

ii. And weddings.

iii. And hen parties where everyone seems to think that squealing ‘He put a ring on it!’ is an acceptable form of congratulations in 2016.

17. On 16 June 2016, you see your phone ringing in front of you on your desk. ‘Mum’ flashes on the screen. She hangs up. She rings again, and again, and again. You ignore it.

a. There’s breaking news on the BBC. The alert interrupts your stream of WhatsApps. The name of your home town, Batley, makes you pay attention.

b. Your MP, the MP at home – proper home – has been stabbed in the town centre. She is being airlifted to hospital.

c. You call your mum back. She’s crying. You can hear shouts in the background – you imagine Janice and Michelle, your mum’s office mates, are having panicked conversations with their husbands and children.

d. ‘Have you seen what they’ve done to her?’ your mum manages to choke out.

18. She was murdered outside the library where you used to borrow books and videotapes.

19. That weekend, after watching a repeat of Mamma Mia! with Jasmine, you book two weeks off work and a return flight to Greece. You’ve had a bottle of wine and three double gin and tonics, but you’ve never been on holiday on your own. You’re feeling reckless, and you never feel reckless.

a. You wonder if you’ll get bored of yourself.

b. You wonder who you’ll talk to.

c. On the plane, you wonder if this is self-care or self-destruction.

d. Reading Heat magazine makes you forget your inevitable death for twenty minutes.

20. You’re desperately lonely in Athens. You thought you were lonely before, but it turned out that was just the origin story of your loneliness.

a. You write a poem about it, go to bed, and fall asleep scrolling through Twitter.

b. The poem is so horrifyingly bad that when you read it back in the morning you laugh at your self-pity.

i. Weirdly, this seems to help snap you out of it and you visit the Acropolis.

21. You stumble across a free night-time city tour on TripAdvisor while eating your tea in a cafe. On the walk, you make friends with an American woman around your age: Rita from Ohio. She’s just finished her MFA in Creative Writing at Evergreen State College and is travelling around Europe for the summer, writing as she goes. She tells you that after Athens she is planning to travel up to Berlin, stopping at Thessaloniki, Sofia, Belgrade and Budapest on the way.

a. At first Rita asks you about Brexit, and you ask her about Trump. You both repeat things you’ve read in the Guardian and the New York Times.

b. You and Rita then find common ground in Katy Perry’s documentary Part of Me, especially the bit where she’s mourning the breakdown of her relationship with Russell Brand.

i. ‘I used to write fanfiction about Russell Brand,’ you say, feeling brave, after two Greek beers. The only other person you have ever told about that is Jasmine.

ii. ‘Really?’ Rita says, delighted. ‘That’s awesome. Do you still write?’

iii. ‘Just Tinder messages,’ you say.

iv. Rita laughs. ‘That’s still writing.’

c. You and Rita go to the open-air cinema in Athens and watch the midnight screening of Mamma Mia!, drink more Greek beer and eat nachos.

22. You stop wearing your hair in a severe bun. People at work tell you that you look younger with your hair down.

a. You let the soft vowels of West Yorkshire, of Kimberley Walsh, Jarvis Cocker and Jane McDonald, curl back over your tongue. It relaxes you. Some days, you think it feels right, whereas at other times you feel like you’re impersonating an older version of your former self.

i. You wonder if that’s appropriation.

b. You hear clients talking about last night’s episode of Love Island as you’re walking out of a meeting. Before you can stop yourself, you’re giving your opinion on if you think an islander is overreacting to another islander’s betrayal in Casa Amour.

c. You find that they – Katie, Sarah and Rhys – smile at you across the meeting room table when you see them again.

i. You start speaking more in meetings.

23. You spend the entirety of Easter bank holiday with Jasmine re-watching Gossip Girl season two, which you both agree is the show’s imperial phase. You wonder why you didn’t realise that Chuck Bass and Blair Waldorf’s relationship was toxic at the time.

a. You open the bottle of Champagne you got for a good performance at work and discuss with Jasmine until her Uber arrives.

b. You pace around your room and feel something close to an epiphany about your relationships with men, identity, romance, society and expectations.

c. Open your MacBook.

d. Close your MacBook.

e. No, fuck it, open your MacBook again.

f. Register for a Wordpress.

g. Call it Gossip Hurl.

h. Finish the Champagne.

i. Write.

j. Write.

k. Write.

24. You never thought writing was hard – it came so easily when you were writing for the university newspaper, or your university essays, or your work reports, or your Russell Brand fanfiction, or your shopping lists, or to-do lists – but fuck is it hard.

a. But you keep doing it.

b. Time seems to glide when you’re writing.

c. You write about Gossip Girl and The OC and Love Island and Riverdale and last night’s episode of Coronation Street.

d. Jasmine is the only person who is allowed to read your blog.

i. But you suspect that she’s sending it to other people because you keep getting more hits.

25. In November, you book a week off work and a return ticket to Batley. Your mum takes you to visit the new shopping centre in the middle of Bradford. After lunch at Pizza Express, you wander around the exhibition on the history of TV at the National Media Museum.

a. You wonder if growing up in a single-parent household where the TV was your babysitter, best friend and father has made you more respectful and reverent of TV.

i. You may have needed to be taught how to pronounce Diptyque but you can talk about the significance of Danny Dyer’s pink dressing gown in EastEnders and what it says about contemporary masculinity.

b. You have your photo taken next to a Dalek in the entrance of the National Media Museum.

i. You caption it: ‘Exterminate me, Daddy.’

ii. It gets 372 likes on Instagram, your most popular post yet.

iii. One of the likes is Sohail, Khadijah’s brother, who you wasted your Sixth Form years on.

iv. You click on his profile. You didn’t even realise he was following you, and see that he is now an accountant, not a poet.

26. That evening, your mum invites Auntie Tina around to watch Strictly Come Dancing. Your mum has made her own glitter paddles out of cardboard, which you hold up at the end of each performance. At the end of the show all three of you cast your votes on your phones.

a. At 11 p.m., when you get up to go to bed, your mum kisses you on the forehead.

b. You open your laptop.

c. Your mum pauses by the door.

i. ‘Are you going to write one of your blogs?’

ii. ‘How did you know about those?’

iii. ‘Your friend Jasmine emails them on to me. They’re always interesting.’

iv. You don’t know what to say.

v. ‘You probably don’t remember, but when you were little you would leave these little stories, these lists about the telly, for me to read. “Reasons Why I Should Be Allowed To Stay Up To Watch EastEnders.” Always made me and Tina crack up.’

vi. You don’t look at your mum. You look at the picture of you on the mantelpiece. It had been fancy dress day at your primary school for Children in Need. You and your mum had taken a cardboard box and made it into a TV, covered in tin foil, with an aerial made out of bright-pink pipe-cleaners. You’d worn it as a headdress and won second prize in assembly for best costume. Your smile is joyous, straining your cheeks.

vii. It sits next to your graduation photo. Both you and your mum look stiff, too formal, out of place.

d. Your mum kisses you on the head and closes the door behind her.

e. You turn back to your laptop and start filling up the blank space.

EDWARD HOGAN

SINGLE SIT

Rising through the Downs, Frank called his 8 o’clocker from the car, half-hoping she’d cancel. He looked out the window as the phone rang. A heatwave had stripped the landscape. Nothing out there but hay-bales and evening shadows.

She picked up.

‘That Mrs Cortez?’ he said.

‘Yep, who’s this?’

The bad news: Mrs Cortez was northern, despite the name. He heard the twang through his speakerphone.

‘Frank McCann, South Coast Conservatories, calling to confirm our appointment.’

‘I almost forgot. I’m finishing dinner, but yes. I’m here.’

‘I’d really like to meet Mister Cortez, too, and show him the designs. Is he there, or is it just yourself, this evening?’

‘Just me.’

‘Right.’ Frank did his little laugh. ‘Only, I know my wife would never let me choose a conservatory, alone. She’s got better taste than me, for starters.’ Frank and Eleanor had been divorced for twenty years.

‘We’re separated,’ Mrs Cortez said. ‘Trust me, Frank. I buy what I want.’

‘Lovely! I’ll be there, presently.’

A revenge conservatory, Frank thought, hanging up. Even if he sold it tonight, the order would be cancelled, eventually. That he’d accepted the lead at all was a sign of how bad things had got for him as a rep (or ‘design consultant’), and for the industry in general. In the 90s he’d have flat out refused a single sit.

A single sit northerner.

On her street, he sat in the car, vaping with the window down. This cul-de-sac of 1960s bungalows, in Woodingdean, had once been a goldmine; he’d done plenty of business here, back in the day, when he worked in windows. The residents had been upwardly mobile, but not too posh for uPVC. Some houses backed onto the South Downs Way, and had sea-views, if you strained your neck.

But his heart sank when he got out the car and walked down the drive. Through the bay window, he saw a wall lined with bookshelves. Middle class people didn’t buy conservatories.

Stay open to the possibility of yes, he told himself as he rang the bell, repeating the mantras from his motivational CDs. You only get what you expect. Keep asking the question.

A tall, broad woman opened the door. Early forties, short shock of brown curls. She held a bowl of noodle soup. ‘You must be Frank,’ she said.

‘I promise I will be!’ His classic opener.

She smiled, revealing big, regular teeth. She wore a grey running vest, the straps of a luminous green sports bra visible on her shoulders. Cut-off leggings like sealskin. Her eyes a glassy green.

She led him through the house: saffron sofas, green rugs, the old walls of the bungalow knocked through. As she slurped the last of her noodles at the kitchen breakfast bar, he noticed a tattoo on the inside of her arm, depicting a ruler like the one Frank’s daughter had used at school. The ruler extended from the wrist, up her forearm, six inches by its own authority. It had the word ‘Shatterproof’ on it.

‘It’s been another stunning day,’ Frank said.

‘Good old global warming.’

‘What would be nice,’ he said, mock-stroking his chin, ‘is if you had some sort of comfortable shelter – a predominantly glass structure, perhaps – from which you could enjoy such pleasant evenings.’

‘Imagine.’

A bass thud came from deep in the bungalow. Frank visualised Señor Cortez in a back room, with a mariachi band and a collection of torture implements, although he got no bad vibes, here. Some houses, you did.

‘My son,’ she said, nodding in the direction of the noise.

‘How old?’

‘Eleven.’ She tapped a photo on the fridge, of a slight kid with thick black hair.

‘Great age. He can help me measure up.’

‘He’s going to bed.’

‘So early?’

‘He has a sleep condition,’ Mrs Cortez whispered.

‘Ah.’

‘So. Frank. How’s business?’

‘Fantastic. We’re very busy on account of this summer offer.’

‘Is that so?’

‘Our builders struggle when the weather turns, so we’ve knocked off thirty percent for a limited time, to get the job done quickly for people like yourself.’

‘I see. You wouldn’t want to be building in mid-winter.’

‘A pain for the fitters, a pain for you. Nobody buys a conservatory for Christmas.’

‘And when does this summer offer finish?’

‘End of August.’

‘I’d better act fast, then.’

Frank wondered if she was taking the piss. ‘You need to be sure, obviously.’

‘What are you going to do, Frank, when the offer finishes? It’ll be much harder to sell at full price, surely.’

‘Well.’

‘Unless,’ she said, holding up a finger. ‘Unless there’s another offer. An autumn offer. And, then … a winter sale.’

She was definitely taking the piss. ‘Conservatories are a luxury item, Mrs Cortez. People pay because they’re reassured by quality. We’re not talking about windows, here.’

Windows, which had lifted the unwanted, half-raised, unteachable teenage Frank out of the 80s dole queue, and given him the money to take a girl like Ellie to the pictures. Windows, which – after Mrs Thatcher sold the council stock to its proud occupants – had bought Frank a house of his own, and then, after the divorce, two smaller houses. Windows, which had granted him country club membership and foreign holidays; which had sent his daughter, Jodie, to university; which had forced the branches of his family tree up towards the light, before the bubble burst.

‘Nothing wrong with windows,’ Mrs Cortez said.

‘It’d be dark in here without them. But a conservatory is a lifestyle choice.’

‘Look, I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I’m being a bitch. I’m a woman on my own, and sometimes I get carried away, trying to show people – men – that I won’t be pushed around.’

‘Wouldn’t dream of it, Mrs Cortez.’

‘I’ll take you through to the garden.’

A dry-stone wall separated her yellow lawn from the Downs. Peachy pink light and blue shadows filled the fields, which sloped away at a crooked angle to the ruled line of the English Channel. On the horizon stood the wind farm: a row of turbines in the sea, arms still.

‘A real suntrap, this garden,’ he said. ‘Perfect for a conservatory.’

He took the iPad from his satchel and opened the design app. ‘Mind if I take a photo?’

‘Sure.’

He put on his spectacles. ‘I’m not used to these glasses. You’ll understand when you get to my age,’ he said, though there was probably only ten years between them. ‘Everything goes.’

‘They’re nice. You look like one of them Italian football managers.’

He hoped she didn’t mean Trapattoni. For a while, he’d copied the younger lads, with their tight trousers, pointy shoes, and that 1940s fighter pilot hairdo, undercut and swept to one side. On Frank, that hairstyle had looked like a comb-over, so he kept it short, now, welcomed the grey, going for the Silver Fox thing.

He took a photo of the house, and waited for it to load. ‘This’ll blow you away,’ he said. He cropped the picture, made the colours vivid. He drag-dropped an image of a Victorian lean-to over the house, to show her how it would look (if the company could afford to pay the suppliers and the fitters didn’t screw it up). But when he zoomed in, he noticed something odd. In the photo, a child stood at the window, though nobody was there, now.

‘That your boy?’ he said, showing her the iPad.

She tilted her head, bit her lip. ‘I’ll go and see if he’s all right.’

After ten minutes, Mrs Cortez returned with two tumblers containing deep red Negronis, orange slices and ice, which she set down on an iron garden table before slumping into a chair.

‘I don’t usually drink on a call,’ Frank said, sitting opposite her. ‘Is your boy okay?’

‘He sleepwalks, basically, and so he worries about going to bed.’

‘My girl was a sleepwalker.’

‘This is extreme.’

‘Once, I went in the kitchen, four in the morning, and Jodie’s standing on a stool, making strawberry cheesecake, totally in a trance.’

‘There are worse things to do in your dreams,’ Mrs Cortez said, glancing back at the house. ‘Before he goes to bed, he practises guitar for hours, and I wonder if he’s over-stimulated.’

‘Could be. You know how we cured Jodie?’

‘How?’

‘Massive bowl of cornflakes before bed. Worked a treat.’

‘It is hard to sleep when you want for things,’ Mrs Cortez said.

‘Exactly.’

Frank gave her the iPad, and explained how to change the dimensions and position of the superimposed lean-to. Mrs Cortez put her feet on the spare chair and worked away happily on the tablet. ‘Tell me about the security aspects of the conservatory,’ she said.

‘Air Force One,’ he said. ‘Triple-lock system.’

‘Good,’ she said. After a while, she put the iPad down, and he saw that she’d been playing Angry Birds 2. Frank sighed, removed his glasses, and took a big gulp of his Negroni.

Some customers followed your lead, and others (men, mainly) tried to dominate, tried to make you talk price too early. But Mrs Cortez didn’t fit any of the categories.