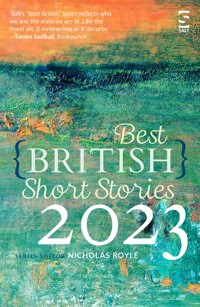

Best British Short Stories 2023 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Best British Short Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

'Best British Short Stories invites you to judge a book by its cover – or more accurately, by its title. This new series aims to reprint the best short stories published in the previous calendar year by British writers, whether based in the UK or elsewhere.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

To the memory of David Wheldon (1950–2021)

NICHOLAS ROYLE

Introduction

TAKING THE FORM OF A HIGHLY SUBJECTIVE ALPHABET OF THE SHORT STORY

A is for anthologies, as distinct from collections. Most people seem happy to go along with the convention that a multi-author volume is known as an anthology, leaving ‘collection’ to describe a book of stories by a single author. Anthologies are how many readers come across short stories and, indeed, new short story writers. Anthologies may be themed or unthemed, consist of all new stories, or a mixture of original pieces and reprints, or be all reprints. Some editors, or series, combine different forms – stories with poetry and essays, for example – but if you love stories you might feel that amounts to taking up space that could have been given to more stories. Some great anthologies: Alberto Manguel’s Black Water: The Anthology of Fantastic Literature, Ramsey Campbell’s New Terrors 1 (and 2, for that matter), Daniel Halpern’s The Art of the Tale: An International Anthology of Short Stories 1945–1985, The Slow Mirror and Other Stories: New Fiction by Jewish Writers edited by Sonja Lyndon and Sylvia Paskin, John Burke’s Tales of Unease, Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction edited by Cris Mazza and Jeffrey DeShell, Kirby McCauley’s Dark Forces, P.E.N. New Fiction I edited by Peter Ackroyd (and follow-up volume II edited by Allan Massie – what a shame there were no more), Giles Gordon’s Beyond the Words: Eleven Writers in Search of a New Fiction and a million others.

B is for JG Ballard, but it could have been for Iain Banks, AL Barker, Clive Barker, Djuna Barnes, Stan Barstow, Alan Beard, John Berger, Jorge Luis Borges, Pierre Bourgeade, Elizabeth Bowen, Ray Bradbury, Richard Brautigan, Christopher Burns, Ron Butlin or Dino Buzatti.

C is for chapbooks. Given that the short story is the best literary form (see F is for form), we need a way to publish individual stories with their own covers, cover art and International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs). Fortunately we have one. It’s called the chapbook. Not all chapbooks have ISBNs, but if publishers go to the trouble and expense of acquiring them, they are then required to supply copies to the copyright libraries, and the libraries are obliged to add them to their collections. That’s nice for authors and readers, as chapbooks are often limited editions and, so, when they’re gone, they’re gone. But, when they’re gone, they’re still available to read at the British Library and other copyright libraries. Chapbooks publishers are often shoestring operations, looking on wistfully as publishers of poetry pamphlets rake in Michael Marks Awards For Poetry Pamphlets worth £5000. There’s no equivalent award for publishers of fiction chapbooks, which could be seen, looking at it in a glass-half-full sort of way, as a gap in the market for philanthropists.

D is for Elspeth Davie, but it could have been for Roald Dahl, Marie Darrieussecq, EL Doctorow, Andre Dubus or Patricia Duncker.

E is for experimental fiction. (See O is for Oulipo.) The short story is the perfect form (see F is for form) for experimental writing. Short stories are by no means easier to write than novels – indeed they may be harder to write and get right – but there’s less at stake, for both writer and reader. If you’re the writer, it might take you a morning, or a week or a month, to get a story right, rather than the six or twelve months or more that the novel might require. So, if you want to gamble, if you want to take a risk, there’s a less at stake. If you’re the reader, what are we talking about? Ten minutes, twenty, half an hour? You, the reader, can also afford to take a risk. If it doesn’t work for you, what have you lost? Half an hour at the most. Have you got ten minutes or twenty minutes or half an hour for BS Johnson or Imogen Reid or Simon Okotie or Joanna Walsh or Will Eaves or Paul Griffiths or Robert Coover or Rikki Ducornet or Tony White or Giles Gordon or David Rose or Susan Daitch (see X is for ‘X ≠ Y’)?

F is for form. Form is how we distinguish between fiction, drama, poetry and non-fiction, and other forms, and how we further distinguish between novel, novella, short story and so on. I’m deliberately not including ‘flash fiction’, because it’s such an awful term, which has somehow taken hold and spread, like dry rot. To be clear, I’m talking about the term, not the work published under that umbrella, but the very nature of the term, with its implications of speed and ephemerality, is, I think, unhelpful. Might it not encourage writers to dash off pieces of so-called flash fiction rather than work at them patiently? David Gaffney, who has published several excellent collections of very short stories, doesn’t dash them off. He writes longer stories and then chips and chisels away at them until they are 150 words long, or whatever. I don’t really know why we need a special term to describe stories that are shorter than average, but if we do, what’s wrong with short short stories, or very short stories, or micro fiction? Anything, frankly, rather than flash fiction. I do recognise that I have a bee in my bonnet about this.

G is for Giles Gordon. Gordon (1940–2003) was mentioned twice in the New Statesman – in a diary piece and subsequently on the letters page – while I was writing this piece. On each occasion he was described as ‘agent Giles Gordon’. It’s true that he was a literary agent and a very good one, with happy clients, but it would be a great shame if we lost sight of the fact that he was also an accomplished and entertaining novelist and short story writer (he also wrote poetry and a memoir) and anthologist. In his short stories – and in his novels, for that matter – he often experimented (see E is for experimental fiction) with style and form, and as an editor he supported writers of experimental fiction (see A is for anthologies). With David Hughes he edited ten volumes of Best Short Stories between 1986 and 1995. One of his own stories, ‘Couple’, was published as a chapbook (see C is for chapbooks) by Sceptre Press of Knotting, Bedford.

H is for horror. Ghost stories are perennially popular. Is it their brevity that appeals? Maybe, partly, but what about big horror novels, Peter Straub’s 500-page Ghost Story, for example? They have their legions of fans, too. Is it that Jamesian (MR, not Henry) idea of sitting around an open fire and being told a story? Is it a mixture of that and the same reason why experimental fiction and the short story are such a good fit (see E is for Experimental fiction)? Horror is an emotion, an uncomfortable, sometimes extreme one. To evoke it in the reader is to take a risk. Alison Moore’s ‘Small Animals’ is only ten pages long, but it’s so intense and your nerves are jangling so much, you wouldn’t want it to be even a page longer. Robert Aickman’s ‘strange stories’ do tend to be longer: twenty pages, thirty, or more. A sinister atmosphere develops, a sense of doom pervades. Will it work, you might ask, in the back of your mind, will he pull it off? The answer is always yes.

I is for idea. Which is how most of those stories we are told around the fire (see H is for horror) actually begin – with an idea, a ‘what if’.

J is for the Jacksons. You’ll know Shirley Jackson, author of ‘The Lottery’ and many other dark stories, but you might not be familiar with her near namesake Shelley Jackson, author of the 2002 short story collection The Melancholy of Anatomy and of the story ‘Skin’, published on the bodies of 2095 volunteers, or ‘Words’, each of whom has had one word from the story tattooed in a specific location of their own choosing. I’m lucky enough to be one of them. My word is ‘After’.

K is for Jamaica Kincaid, but it could have been for Franz Kafka, Anna Kavan, James Kelman, Heinrich von Kleist or Hanif Kureishi.

L is for Clarice Lispector. Her short story, ‘The Imitation of the Rose’, reprinted in Other Fires: Stories From the Women of Latin America edited by Alberto Manguel (see M is for Alberto Manguel), is an account of mental illness as powerful, in its own subtle way, as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ (see U is for Errol Undercliffe).

M is for Alberto Manguel. They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes – actually, don’t they also say you shouldn’t even have heroes? – but I met Manguel, the editor of Black Water: The Anthology of Fantastic Literature and White Fire: Further Fantastic Literature, and he was charming, generous and entertaining. We bonded over sky-blue shoelaces.

N is for Gary Numan. I remember reading, as a 16-year-old, probably in Smash Hits or the NME, about Numan’s dabbling in literature. The Tubeway Army frontman, who captured the imagination of fans with his lyrics about electric ‘friends’ and ‘Machmen’, had written science fiction stories before he started recording music. I wanted to read those stories. I still do.

O is for Oulipo. (See E is for experimental fiction.) Oulipo – short for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, which translates as Workshop For Potential Literature – was formed in France in 1960 by writer Raymond Queneau and mathematician François Le Lionnais. They encouraged the practice of writing under specific constraints. Many writers have enthusiastically taken up the baton, some of whom are featured in The Penguin Book of Oulipo edited by Philip Terry.

P is for Penguin Modern Stories. This quarterly anthology series edited by Judith Burnley ran from 1969 to 1972, featuring three to five writers in each volume, with between one and three stories from each writer. It finished after twelve volumes. Stories were appearing for the first time in the UK and were by a mixture of established writers and new names. Design was by David Pelham, using bold, solid colours, a different one for each book, with the number appearing in large, white type on both front and back covers. You see them now and again in charity shops and second-hand bookshops. If you’re lucky you might spot a multicoloured box set including volumes one to six. The series kicked off with William Sansom (see S is for William Sansom) joined by Jean Rhys, David Plante and Bernard Malamud. Other notable writers who appeared as the series proceeded included Sylvia Plath, Margaret Drabble, Giles Gordon (see G is for Giles Gordon), Elizabeth Taylor, BS Johnson, William Trevor, Jennifer Dawson and Gabriel Josipovici. If you do see one – a box set or a single volume – they’re well worth picking up.

Q is for questions. I like to be left with more of them than answers. The short story is perfect for that.

R is for Alain Robbe-Grillet, whose status as a short story writer is out of proportion to the number of stories he actually published. The slim volume Instantanés published by Editions de Minuit in 1962, and issued in translation as Snapshots, contained six stories, two of which, ‘La plage’ (‘The Beach’) and ‘Dans les couloirs du métropolitain’ (‘In the Corridors of the Métro’), have been reprinted in various places. Both stories exemplify a tendency towards repetition of image and narrative within a story that is characteristic of the nouveau roman (new novel), of which Robbe-Grillet was a key exponent. The unfurling of waves on a beach and the constant motion of an escalator create infinite loops within which we see actions appear to repeat themselves, with uncanny effects.

S is for William Sansom, but it could have been for Saki, James Salter, Greg Sanders, Bruno Schulz, Ellis Sharp, Alan Sillitoe, Clive Sinclair, Muriel Spark or Robert Stone.

T is for tense, which is what I become when I think about a certain highly regarded writer, who wrote – more than a decade ago now, but I can’t get it out of my head – of his displeasure at how often the present tense was being used in the contemporary English novel. I took his first short story collection down from the shelf, curious to see if it included any stories in the present tense. It does: two. The use of the present tense in those two stories does not especially distinguish them from the other stories in the collection. The present tense is there for writers to use, whether in the novel or in the short story. Use it well and readers will be happy.

U is for Errol Undercliffe. Horror (see H is for horror) maestro Ramsey Campbell’s 1973 collection Demons By Daylight was, interestingly, divided into three parts: ‘Nightmares’ opened the collection and ‘Relationships’ closed it. Caught between the two was the curious and fascinating ‘Errol Undercliffe: a tribute’, which comprised a short biographical note about Undercliffe, ‘a Brichester writer whose work has only recently begun to reach a wider public’, a first-person piece narrated by ‘Campbell’ entitled ‘The Franklyn Paragraphs’ that reads, at least to begin with, like a memoir, and a short story, ‘The Interloper’, by Undercliffe. I put ‘Campbell’ in inverted commas, because ‘The Franklyn Paragraphs’ is Campbell’s fiction, as is ‘The Interloper’, of course, since both Undercliffe and Brichester are his invention. In ‘The Franklyn Paragraphs’, the narrator visits Undercliffe’s flat after the disappearance of the Brichester writer: ‘The wallpaper had a Charlotte Perkins Gilman look; once Undercliffe complained that “such an absurd story should have used up an inspiration which I could work into one of my best tales.”’ (See L is for Clarice Lispector.) Campbell’s opinion of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ is higher than Undercliffe’s: he included it in The Folio Book of Horror Stories, which he edited for the Folio Society in 2018.

V is for Boris Vian. Another author with a pseudonym (Ramsey Campbell also published a novel as Jay Ramsay), Boris Vian was a novelist, short story writer, poet, musician, singer and critic, who published some of his work, a string of controversial crime novels, under the name Vernon Sullivan. Of Vian’s four short story collections, two were published posthumously (he died young, at 39). Le loup-garou (The Werewolf), the second of these, kicks off with ‘Le loup-garou’, in which a wolf turns into a man, but only on the full moon, a clever inversion of the myth. ‘Martin m’a téléphoné’ is a jazz story, about picking up gigs in clubs. ‘Les chiens, le désir et la mort’ was originally published under the Sullivan pseudonym and is one of the strongest stories in the collection, a fatalistic noir piece about a taxi driver who picks up a fare he probably should have left waiting on the sidewalk.

W is for Paul Willems. Belgian novelist, playwright and short story writer Paul Willems (1912–97) published two collections towards the end of his life. La cathédrale de brume was the first of these and is available in English translation, as The Cathedral of Mist, from US-based Wakefield Press. Willems came from near Antwerp, but wrote in French. ‘Requiem pour le pain’ begins with the narrator’s cousin explaining to him that the reason his grandmother told him to break bread with his hands rather than cut it with a knife was because the moment a knife touches bread, the bread cries out. Moments later, the cousin falls out of a window to her death and the narrator’s grandmother reassures him that his cousin will be in paradise, more precisely in a pension in Ostend for dead little girls. Ballard (see B is for JG Ballard) was a fan of the Belgian artist Paul Delvaux. Maybe he also knew of Willems’ work. Ostend, the narrator of Willems’ story tells us, is submerged by the sea during the night. Only in the morning do the waves recede. This reminds us of the opening of Ballard’s story ‘Now Wakes the Sea’: ‘Again at night Mason heard the sounds of the approaching sea, the muffled thunder of breakers rolling up the near-by streets.’ Another of Willems’ stories, ‘Tchiripisch’, is set in Bulgaria, but the narrator of that story remembers a dream he had in Ostend. He could hear waves breaking on the beach (see Z is for Curtis Zahn) and it seemed to him that they uttered two words, one as they broke and another as they withdrew, taking back the first word. What the words were was not, in the end, revealed to him.

X is for ‘X ≠ Y’. This story, by the American novelist and short story writer Susan Daitch, was published in Bomb magazine in 1987, according to bombmagazine.org, where you can read it online, but I read it in After Yesterday’s Crash: The Avant-Pop Anthology (Penguin) edited by Larry McCaffery, which gives the story a copyright date of 1988. It’s a tense, effective and, I think it’s accurate to say, experimental account of a plane hi-jacking from the point of view of a passenger. McCaffery’s anthology also includes an extract from Steve Erickson’s novel Arc d’X, which I mention in spite of its being a novel extract rather than a short story simply because Erickson is so good, and a story by Marc Laidlaw, ‘Great Breakthroughs in Darkness (Being Early Entries From The Secret Encyclopaedia of Photography)’, that uses a similar alphabetical device to this essay but doesn’t get any further than ‘Acetylide emulsion’.

Y is for Elizabeth Young. Best known as a critic (her critical essays were collected in Pandora’s Handbag), Elizabeth Young was also a brilliant short story writer, who died too young (in 2001, at the age of 50) and before she could publish enough stories to think about putting together a collection. In the 1990s I had a number of opportunities to invite her to write new stories, which she duly supplied and which appeared in anthologies like Darklands 2, The Ex Files, The Time Out Book of London Short Stories Volume 2 and elsewhere. Her story ‘Shrinking’ in The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories is one of the best stories about multiple personality disorder, crack addition and therapy that you are ever likely to read.

Z is for Curtis Zahn. The US author’s collection American Contemporary was published in the UK by Jonathan Cape in 1965. His sharp observational gifts, with his eye focused mostly on Californian society of the 1950s and 1960s, and some of his ideas – in one story, doctors surgically remove a character’s conscience – might remind readers of Philip K Dick. A couple of lines about the call of the surf – ‘… the surf called to us monotonously above the murmuring of marsh birds in the great swamp’; ‘But now the surf came to us, reminding us of our task, confessing in its tortured tumbling that aggressions had been stored up for some time’ – remind me also of Raymond Chandler and my favourite line from The Big Sleep: ‘Under the thinning fog the surf curled and creamed, almost without sound, like a thought trying to form itself on the edge of consciousness.’ When reading the 1968 Penguin edition of American Contemporary earlier this year, I felt that my thoughts about Curtis Zahn’s stories were trying to form themselves on the edge of consciousness, so hard were they, in some cases, to pin down, but maybe this was deliberate. One story, ‘A View From the Sky’, was reprinted in 1971 in Anti-Story: An Anthology of Experimental Fiction (Free Press) edited by Philip Stevick, included in a section headed ‘Against Subject: fiction in search of something to be about’ (see E is for experimental fiction). In his introduction, Stevick writes, ‘Nearly any classic story can be said, with a kind of simple accuracy, ‘to be “about” some abstraction … There is, however, no intrinsic reason why a short fiction, or any other literary work, should be so constructed as to provide us with an answer to our preliminary question of what its subject is … Is it possible to have a fiction that is coherent on its own terms but so tentative and exploratory that its writer seems never entirely clear what its centre is, not even at its end? Can we ever assume that a writer knows what he is doing but does not know what his subject is?’ (See Q is for questions.)

nicholas royleManchesterJuly 2023

MILES GREENWOOD

Islands

one time, a daughter was born to a mother and a father on an island. their way of life was an old one. they lived with the land to grow just enough food for themselves and their neighbours, and their neighbours did the same. yam coconut soursop callaloo breadfruit. almost-ripe mango swelled the trees and could be smelt on the fresh air. goats cows and chickens too. nature provided more than food as well. birds would offer their song in the day to a backdrop of the cool breeze rustling the leaves as it swept through the green hills. crickets would chirp at night, frogs would croak and rain would beat on the zinc roof of the house that the daughter the mother and the father lived in, nestled in the hills of the island.

the daughter thought this life was hard. all she did was work.

fetching water from the spring high up in the hills in the morning

chop sugar cane and cut grass to feed the cows in the afternoon

she would cut some of the sugar cane to taste the sweet sweet juices on her thirsty tongue

don’t tell the mother in case she get a beating with a stick of choice

sweep the house

wash the clothes.

the daughter thought she could manage this life if it wasn’t for the mother and father having more daughters and a son. now the daughter had to look after the sisters and the brother. now there was no time and no money for school to get the book learning that the daughter loved.

yes, all she did was work

she had to learn to cook and feed many with what they grew from the land

soup made with green banana and yellow yam from the garden

hot pepper and thyme from the garden

pumpkin from a neighbour

carrots from a cousin

fish brought from the market at the old harbour by the father.

the daughter seasoned the fish and fried enough for the family and the neighbours so that none went hungry. she served it with roast breadfruit and steamed callaloo. they all ate.

the mother

the father

the sisters

the brother

the neighbour

and the cousin

the daughter was becoming a woman. a pretty one with bright eyes with a hint of sadness to them. she had dimples that sat each side of her cheek whether she smiled or not. some thought she was the prettiest woman on the island. the daughter had no time to worry about this pretty business. her mother had spat on the ground and told her to return from the shop with spices before it dried. the shop was run by a father but a son stood behind the counter that day. a handsome man, she thought. older than she. nice smile. she could feel the beating she would get from the mother with a stick of choice for ignoring her warning.

don’t talk to strange men

don’t look pon them

don’t think of them.

but the son was nice. many thought it, but he was the first to say that she was the prettiest girl on the island when she walked into the shop that day. he was going foreign, he said, and he would like to write to her. this was the most exciting thing she ever heard. this son was taking a boat across the big blue sea to another land and of all the daughters on the island, he wanted to write to her.

the son did write to the daughter. he wrote of a cold island with brick houses two, three storeys high with fire inside. more white people lived there than the daughter could imagine, he said. more letters followed. a longing crept into her chest.

then that letter came.

the letter that said the son wanted the daughter to come foreign and marry him. this was the most exciting thing she ever heard. this was the scariest thing she ever heard.

what business did she have in foreign

why could she not go foreign and marry the son

she was too young to marry the son

she was a woman now

she would have to ask the mother and the father

she could feel the beating she would get from the mother with a stick of choice for ignoring her warning.

don’t talk to strange men

don’t look pon them

don’t think of them

don’t marry them.

ask the mother and the father she did. no beating came. the father’s face turned serious and sad. the mother kissed her teeth before the silence. then the daughter had to wait to catch fragments of hushed conversations from the bedroom of the mother and the father.

too young

a stranger

a beating

better life

silence.

the mother and the father held the daughter like they did when she was born to this world. the father pressed a five pound note into her hand and said no more. she got on the bus with the neighbours who were heading to the market for fish. she would not return with them. she was to go further.

don’t look back

fix yuh eyes forward.

the bus creeped down the bumpy, winding road from the hills. the daughter noticed the soil change from the deep red of home to a yellow like the yam in her soup. the bus reached the old harbour and the neighbours left one by one, each squeezing her hands and wishing her well. then strangers replaced them on the road by the big blue sea that followed the coast to the city.

don’t look back

fix yuh eyes forward.

the son crossed the big blue sea by boat. she was to cross in an airplane with the birds in the sky. a mixture of fear and excitement tumbled around in her belly as she was pressed back in her seat as the plane ramped up to top speed. a woman next to her prayed to her god to take everyone’s lives in their hands. may they guide and protect us.

amen.

the plane floated into the air and the daughter shared in everyone’s relief. she could see the island and the hills. if she squeezed her eyes she might see home, the father the mother the sisters the brother.

don’t look back

fix yuh eyes forward

but with her eyes fixed forward, the daughter didn’t notice those unseen threads unravelling around her.

the foreign island was so cold that the daughter felt frozen to her soul. even when she saw the son, and he wrapped her in his coat and under his arm, she could not stop her bones from shivering. he told her again that she was still the prettiest girl on the island. she wasn’t sure whether she believed him with all these pretty people on this cold island.

the daughter and the son took the two-storey bus to the son’s three-storey house. she soon realised that the son occupied one box room in the three-storey house with nine other people from the island and other islands. this wasn’t what the daughter expected of the foreign island with its brick houses white people and fires.

the daughter began to unpack while the son looked on with expectation in his eyes.

yuh bring breadfruit and callaloo, he asked.

she forgot. in the last letter the son sent to the island from foreign, he asked her to bring breadfruit and callaloo. she thought it strange that he would want breadfruit and callaloo when he has all those bricks and white people, and she put it so far to the back of her mind that it got stuck there.

why she forget, the daughter asked herself.

she expected the son to get angry and could feel a beating with a stick of choice, but now the son would be the punisher instead of the mother. she didn’t know this son she was to marry after all. but he just looked sad.

it’s ok don’t worry yuhself, he said in his gentle way she would grow to love over time.

the son wanted to get busy and so they got married quick at a local church in borrowed clothes from neighbours, surrounded by the son’s friends. the daughter was nervous and curious about this busy business. she didn’t enjoy it the first time but it wasn’t so bad the second. before she knew it,

one child

two child

three child.

and then she was vexed. all the daughter did was work.

she washed and ironed clothes

she sent the children to get their book learning while the son went off to work in a factory

she cleaned the two-bedroom house they now lived in

she went off to the hospital to look after white people who said evil things to her

she would come home tired. but she still had to make soup.

green banana, yam, dumplings, thyme, hot pepper and chicken all from the market. she can’t afford any fish to fry. she can’t get breadfruit and callaloo on this cold island.

why she forget the breadfruit and callaloo.

all she did was work. and they still struggled to pay the bills. one day the son had an accident at work.

hit by a truck, they said

he won’t walk again, the doctor said.

the daughter had to take another job sewing clothes while the son and the children slept. sometimes she felt a temptation creeping in her heart to look back and ask, before a sadness distracted her. sometimes eye water rolled down her face.

don’t look back

fix yuh eyes forward.

the children grew. they got their book learning. they got jobs too. had their own families. grandchildren to love and the son and daughter loved them with all their hearts. loved them enough to warm the cold of this island. the daughter was able to retire. she was able to make soup for grandchildren.

why she forget the breadfruit and callaloo.

no matter. the grandchildren ate and they were happy and she loved them. there’s one grandson that held a special place in the daughter’s heart. strange boy. nice boy. quiet. head full of thoughts and questions.

where does the green banana come from

where does the yam come from

where does the hot pepper come from

strange boy.

when the grandson grew older. he told the daughter that he wanted to go to the island and the hills and to the home. this made the daughter nervous.

why him want to look back.

but there was an excitement like what she felt when she left the island to go foreign. she had to unfix her eyes and look back.

back to the ocean

the road

the hills

the family

the home.

she told him, when yuh the plane drops from the sky it will feel as though it will drop into the sea but the runway will catch yuh. then take the road from the city along by the big blue sea until yuh reach the old harbour. from there take the bumpy and windy road into the hills where we grow fruits of all kinds. make sure yuh try the breadfruit and callaloo. when the earth turns a deep red colour like rust, you will be near. ask for directions to the father’s house at the shop.

the grandson followed the daughter’s instructions. when he arrived he thought it was the most beautiful place he ever saw. hills cloaked in green trees bearing fruits he didn’t know. a cool breeze wrapped around him carrying the smell of ripe mango. a smell he did recognise from the markets of the cold island but this smell was fresher. sweeter.

he did not find the father or the mother. he did find gravestones at the front of a house he was told was the father’s. he did not find the daughters. they had moved away, he was told. some to other parts of the island. some to foreign islands. the grandson did find the son of the father, the brother of the daughter though. the son greeted the grandson as if he was his own.

held him tight

looked him up and down

took him in

gave him a cold coconut to drink from

introduced him to a family

children

grandchildren

cousins

they prepared a meal of

saltfish

callaloo

breadfruit and dumplings.

the meal tasted familiar and unfamiliar. like a distant memory half forgotten. the food was shared with the whole family and with neighbours. nobody went hungry. everyone was looked after. he listened to the bird’s song in the day, the frogs croaking and the crickets chirping at night only for them to be silenced by the rain that beat on the zinc roof of the home.

the grandson went with the son to chop cane and cut grass to feed the cows in the morning.

is this your land, the grandson asked.

nuh, this is our land, the son said. extending his arms over the hills to foreign islands.

when they returned through the village, the son introduced the grandson to everyone.

this is my nephew from foreign, he would say

this is yuh cousin, he would also say, about everyone it seemed.

the grandson fell in love with this life, this family and this island. but he knew that he must return to the cold island. part of him would always be on this island, in these hills though. and one day he would take his children too. but for now, he had to go back.

and he would bring breadfruit and callaloo.

LYDIA GILL

The Lowing

It was only a short walk from the farmhouse to the barn.

The moon was a bright hole in the sky, letting a thin veil of light creep into the dark. The farmer had no torch.

The dog stood up in the kennel.

‘Heel.’ The farmer’s voice sliced the air with white and the dog folded to the floor.

A persistent wind had blown the snow over and over itself, until it swooned in tired drifts against the drystone walls. Now the snow lay thick and lifeless, pricked by splinters of frost, face upturned to the sky.

It was the silence that had coaxed the farmer outside.

For three days and nights the cows had been calling for their calves. Each year, the weaning began with the relentless lowing of the mothers, their restless stamping, their udders swollen, their saliva hanging in threads and falling to the ground.

And each year the farmer forgot how the sound would take hold of his limbs, pull him out of sleep, and rake its claws across his skin, until he allowed himself to be held and rocked. And where the noise had pierced him, pain leaked out. Milk streaked with blood.

But now there was no noise.

It was only a short walk from the farmhouse to the barn.

The calves were not far away, gathered and soft. The smell of their fear seeped across wheels of hay, the sweet earth of it, reaching into the shadows of the byre, searching for their mothers.

The calves were not far away at all.

But the snow was deceptive in its quietude. Secretly deep and unyielding. The farmer’s boots staggered into drifts, and stuck. Each step wrenching, one foot to the next.

The dog stood up in the kennel. ‘Heel,’ said the farmer.

Somewhere a cow bell rang. It was nothing at first, the clear roundness of the sound, the familiarity. How it smelled like the sun on grass. How the warmth of it spread through him like a child’s laugh. How it lingered in the air, waiting.

But they didn’t bell the cows anymore.

And the sudden knowing of this resounded through the farmer, discordant and cold. He shook himself down, billowing white lungfuls of air into the night, his eyes searching the darkness.

But the darkness would not move.

The moon had fallen behind the looming trees, and stars began to crowd the sky, watching with pinprick eyes. Waiting.

It was only a short walk from the farmhouse to the barn. Past silage bales that sagged and split into piles, grass growing from their openings. But the farmer hadn’t reached the barn yet. His boots were heavy with snow, his legs were heavy with cold, and he felt the weight of the dark upon his back.

The dog stood up in the kennel. Cocked its head. Licked its teeth. ‘Come here, boy,’ the farmer reached out. ‘Boy,’ he growled. The dog stood still in the kennel.

The wind softly brushed the snow. Brushed it into a sheet at the farmer’s feet. And on the sheet were three drops of blood, each one closer to the barn. An invitation written on white. A calling.

One. Two. Three.

Beyond, something lay in the snow. A twist of gore. A gleam of blood. A clot of flesh. The warmth of it steamed into the air.

A cow bell rang.

The farmer creased into himself, stumbling back, the bone of a cry caught in his throat, his hands feeling along the loose stones of the wall. The stones fell away. They would not hold him. The wind had dropped, and the trees held onto their outlines, arms outstretched and willing.

It was only a short walk from the farmhouse to the barn. And the cows knew this too, as they watched from their dark places. Shifting bulks of shadow in the heart of the barn.

The farmer fell to his knees. Gave himself, face down, to the snow. Something made of blood was in his way.

The dog stood up in the kennel. ‘Heel,’ growled the dog.

A cow bell rang. Rang just as the farmer reached to touch the thing of blood in the snow. And when he looked at the heft of his hand, he saw the dirt that lived in the grain of his skin. What was frozen melted under his breath. And the round of his cry left a hole.

It was only a short walk from the farmhouse to the barn. A short walk, even for a woman with a child hidden in the depths of her. Hidden from the dark and unknown edges of the farm. From those who separated mothers from their young.

It was only a short run, for a woman pursued. But she had never reached the barn.

It was only a short walk from the farmhouse to the barn, so it didn’t take them long to find the farmer in the morning.

And they remarked how the dog was watching from the kennel. And how it looked as if the snow had left a blank space. How it had erased something.

And they wondered why the farmer had made his way to the old barn in the night. The cows had all been sold a few years back.

‘After,’ they said, and coughed against the thought of it. Coughed out the remembering. The remembering of the cold that had carved her into stone. Of the frost that had swirled all her blood into fronds. And the things in the snow that they would never name.

Beyond the drystone walls of the farm, the moors swelled into skin-white hills and trees grew in patches, untamed.

As they lifted the farmer’s frozen body, they were surprised at its lightness. And how his hand stayed reaching for the barn.

And how he barely left an imprint in the snow.

DAVID WHELDON

The Statistics Rebellion

The building, of local Pennant sandstone, is tall and narrow. Once a hotel associated with the nearby railway station, it is now part of the university; it houses the epidemiology and medical statistics departments.