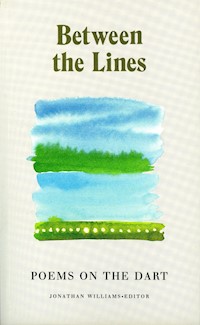

Between The Lines E-Book

4,80 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

One hundred and forty-four poems were selected by the editor from the two hundred or so displayed on DART carriages between 1987 and 1994: short enough for passengers to read without missing their stops, resonant enough to inspire reflection, disquietude or delight. Three were written especially for Dublin's train travellers, and about half of them are by Irish poets. Featuring poetry by Yeats, Dickinson, Larkin, Eliot, Synge, Auden, Heaney, Beckett, Blake, Frost, Muldoon, Shakespeare, Hardy, Montague, Wilde, Joyce, Milton, Coleridge, E.E. Cummings, Tennyson, Rossetti, Flann O'Brien, Longley, the Bronte sisters, and many more.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1993

Ähnliche

Between the Lines

Poems on the DART

JONATHAN WILLIAMS EDITOR

THE LILLIPUT PRESS MCMXCIV

To the man on the 7.22 a.m. from Kilbarrack

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Beautiful Lofty Things W.B. Yeats

Int en gaires asin tsail Anonymous

A bird is calling from the willow Thomas Kinsella

Untitled Emily Dickinson

Talking in Bed Philip Larkin

Gaineamh shúraic Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill

Quicksand Michael Hartnett

Sic Vita Henry King

Roundelay Samuel Beckett

Prelude John M. Synge

Dublin 4 Seamus Heaney

Mirror John Updike

Remember Christina Rossetti

Not Waving But Drowning Stevie Smith

Corner Seat Louis MacNeice

Uaigneas Brendan Behan

Loneliness Brendan Behan

Anecdote of the Jar Wallace Stevens

Fire and Ice Robert Frost

I May, I Might, I Must Marianne Moore

A Part of Speech Joseph Brodsky

Ar Aíocht Dom Máirtín Ó Direáin

A Melancholy Love Sheila Wingfield

Liffey Bridge Oliver St John Gogarty

Fin Liz Lochhead

Séasúir Cathal Ó Searcaigh

Seasons Thomas McCarthy

The Sick Rose William Blake

Farewell Anne Brontë

Night Train Craig Raine

Prelude T.S. Eliot

The Emigrant Irish Eavan Boland

Cock-Crow Edward Thomas

Rousseau na Gaeltachta Seán Ó Tuama

A Gaeltacht Rousseau Seán Ó Tuama

The Eagle Alfred, Lord Tennyson

The Boundary Commission Paul Muldoon

The Cocks Boris Pasternak/trans. J.M. Cohen

Last Hill in a Vista Louise Bogan

Pharao’s Daughter Michael Moran (‘Zozimus’)

Chinese Winter F.R. Higgins

Flowers by the Sea William Carlos Williams

To My Daughter Betty Thomas Kettle

Boy Bathing Denis Devlin

A Dying Art Derek Mahon

Holy Sonnet John Donne

A Farm Picture Walt Whitman

In the Middle of the Road Elizabeth Bishop

Sonnet 94 William Shakespeare

Double Negative Richard Murphy

To Norline Derek Walcott

Reo Seán Ó Ríordáin

Frozen Valentin Iremonger

Sonnet 15 Anthony Cronin

Moonrise Gerard Manley Hopkins

Scholar Seamus Deane

Sonnet from the Portuguese XXII Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Home Francis Ledwidge

To My Dear and Loving Husband Anne Bradstreet

Leannáin Michael Davitt

Lovers Philip Casey

Four Ducks on a Pond William Allingham

The Oil Lamp Rory Brennan

Untitled Osip Mandelstam/trans. Clarence Brown and W.S. Merwin

Secrecy Austin Clarke

Cré na Mná Tí Máire Mhac an tSaoi

The Housewife’s Credo Máire Mhac an tSaoi

A Lullaby Randall Jarrell

Heredity Thomas Hardy

Pygmalion’s Image Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

Merlin Geoffrey Hill

Les oiseaux continuent à chanter Anise Koltz

The birds will still sing John Montague

Nana Rafael Alberti

Lullaby Michael Smith

Fís Dheireanach Eoghain Rua Uí Shúilleabháin Michael Hartnett

The Last Vision of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin Michael Hartnett

Vuilniszakken Victor Vroomkoning

Rubbish Bags Dennis O’Driscoll and Peter van de Kamp

Di te non scriverò Elena Clementelli

I will not write of you Catherine O’Brien

Na h-Eilthirich Iain Crichton Smith

The Exiles Iain Crichton Smith

Fotografierne Benny Andersen

Photographs Alexander Taylor

Història Joan Brossa

History Susan Schreibman

Border Lake John Montague

First Fig Edna St Vincent Millay

She Tells Her Love While Half Asleep Robert Graves

How dear to me the hour Thomas Moore

Thought of Dedalus Hugh Maxton

Heraclitus William Johnson Cory

Cléithín Gabriel Rosenstock

Splint Gabriel Rosenstock

Pot Burial Tom Paulin

Political Greatness Percy Bysshe Shelley

Sonnet VIII Thomas Caulfield Irwin

Fear Charles Simic

To a Fat Lady Seen from the Train Frances Cornford

Throwing the Beads Seán Dunne

To My Inhaler Gerald Dawe

au pair girl Ian Hamilton Finlay

Les Silhouettes Oscar Wilde

The Distances John Hewitt

Song John Clare

Anthem for Doomed Youth Wilfred Owen

Above the Dock T.E. Hulme

Proof Brendan Kennelly

Tilly James Joyce

Two Winos Ciaran Carson

Once it was the colour of saying Dylan Thomas

Piazza di Spagna, Early Morning Richard Wilbur

Body Padraic Fallon

Work Without Hope Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The Demolition Anne Stevenson

October Patrick Kavanagh

Requiem, Robert Louis Stevenson

3 A.M. Dennis O’Driscoll

Taxman George Mackay Brown

The Bed Thom Gunn

My Mother Medbh McGuckian

The Five Senses Dermot Healy

The Death of Irish Aidan Mathews

Variations on a Theme of Chardin Ruth Valentine

Sonnet XX (On his Blindness) John Milton

Frozen Rain Michael Longley

Vengeance Padraic Fiacc

Old Age Edmund Waller

Dolor Theodore Roethke

Post-script: for Gweno Alun Lewis

Asleep in the City Michael Smith

Retreat Anthony Hecht

Sa Chaife Liam Ó Muirthile

In the Café Eoghan Ó hAnluain

Under the Stairs Frank Ormsby

Untitled e.e. cummings

Mrs Sweeney Paula Meehan

The Tired Scribe Brian O’Nolan

Gare du Midi W.H. Auden

Love and Friendship Emily Brontë

Their Laughter Peter Sirr

Untitled Thomas Kinsella

The Bright Field R.S. Thomas

Biographical notes

Acknowledgments

Index of titles

Index of poets and translators

Index of first lines

Copyright

Introduction

In May 1986, after nine years away from Ireland, I first stepped into a DART train, finding it a ‘clean, well-lighted place’ after the subways of New York and Chicago. Four months before, in London, Poems on the Underground had been launched, and the sight of those first poems on the District line made me long to do the same for Dublin on my return. Soon, with the enthusiastic collaboration of Raymond Kyne and Jim and Marianne Mays, Poetry in Motion was formed; the raison d’être of the scheme was to make poetry available to those who, otherwise, might have too little time, or even inclination, to read it.

The first two Poems on the DART went up in January 1987. Displaying the work of Irish poets would be a primary consideration. ‘Beautiful Lofty Things’, by W.B. Yeats, was chosen because of its reference to ‘Maud Gonne at Howth station waiting a train’. The second—a ninth-century nature poem in Irish, with a translation by Thomas Kinsella—is typical of many glosses found in the margins of monastic manuscripts, and signalled our commitment to presenting work in the Irish language.

Unlike our London counterparts, who from time to time put up extracts from long poems—Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ and Keats’s ‘Endymion’, for instance, we decided to display only complete poems, doubtless intimidated by the entire body of world poetry on which we could draw. (The single exception—discovered too late!—is Edmund Waller’s ‘Old Age’, which derives from the last two stanzas of ‘Of the Last Verses in the Book’, Poems [1686].) Our graphic designer, Raymond Kyne, established an upper limit of fourteen or (occasionally) fifteen lines, whilst retaining legibility, and this enabled us to include the sonnet. We had made our Procrustean bed and now would have to lie on it.

Immediately it became clear that the work of some fine poets would have to be jettisoned because they wrote so sparingly in the short form; but this, ironically, proved a blessing because it helped us to whittle down the vast range of literature open to us.

The poems in Between the Lines exhibit, we hope, a variety of moods, subject matter and tones. The eternal themes—love, death, war, the passage of time, memory, the seasons, the natural world—are represented; others were put up to mark particular events or occasions. These include the centenaries of the births of T.S. Eliot, Osip Mandelstam and Francis Ledwidge; the Dublin Millennium in 1988; separate visits to Dublin by Joseph Brodsky and Derek Walcott, who both read (Brodsky in Russian and English) their poems in trains in Dún Laoghaire station; Randall Jarrell’s scornful lullaby coincided with the deployment of American troops in the Kuwaiti desert; and during Dublin’s year as European City of Culture, in 1991, we presented the work of two living poets from each member state of the European Community, in Catalan, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Irish, Italian, Portuguese, Scots Gaelic, Spanish and Welsh, and in English translation.

From the start, we resolved that half our bi-monthly selection of eight poems would be by Irish poets, but otherwise we have no manifesto, no literary axes to grind. The essential criterion is that the poems will cause a smile, give comfort, disturb, provoke, or simply entertain. The impulse is to set these poems free from the books in which they are locked, often unread by the tens of thousands of DART travellers. Exceptions were Seamus Heaney, Craig Raine and Hugh Maxton, who wrote expressly for Poems on the DART.

Encouragement arrived in letters from the public, commenting on individual lines and praising favourite poems. A few items of correspondence stand out: a postcard, written on the journey south out of Dublin and mailed in Bray, from a woman moved by Christina Rossetti’s ‘Remember’; two separate requests for the words of Anne Brontë’s ‘Farewell’ (many months after it had been taken down), so that they could be incised on the gravestones of people who had died tragically young; a man who had remembered only the last line of Derek Walcott’s ‘To Norline’ (again months after its removal), who wanted to have the full poem; and many letters requesting copies of the original DART cards (the concrete poems by John Updike and Ian Hamilton Finlay were especially popular).

Whether or not we have chosen the best short poem by any of these poets is a matter for others to determine. With some, there was a lot of wavering. Which poems by Hardy, Frost and Joyce, which Shakespeare sonnet, should go up in the carriages? In these and in other cases, we canvassed widely, and we never resisted picking a poem that might be well known to many passengers; there are always new readers to win over.

So far, no poet has appeared more than once, unless he or she is represented by the translation of another poet, yet there are legions still to come: Ben Jonson, Swift, Wordsworth, Housman, de la Mare, Miroslav Holub, Tony Harrison, and a slew of new Irish poets. In future years, with the continued support of Cyril Ferris and Iarnród Eireann, we would like to give space to voices from the Caribbean, Africa and Canada, and perhaps to display over one two-month period poems for, and even by, children.

Between the Lines contains roughly three-quarters of the nearly 200 poems that have journeyed from Bray to Howth and back, presented in the order in which they appeared in the trains. Liberated for a couple of months from the confines of the printed page, they are now returned to where they traditionally belong.

JONATHAN WILLIAMSSandycove, County DublinNovember 1994

Between the Lines

Beautiful Lofty Things

Beautiful lofty things: O’Leary’s noble head;

My father upon the Abbey stage, before him a raging crowd:

‘This Land of Saints,’ and then as the applause died out,

‘Of plaster Saints’; his beautiful mischievous head thrown back.

Standish O’Grady supporting himself between the tables

Speaking to a drunken audience high nonsensical words;

Augusta Gregory seated at her great ormolu table,

Her eightieth winter approaching: ‘Yesterday he threatened my life.

I told him that nightly from six to seven I sat at this table,

The blinds drawn up’; Maud Gonne at Howth station waiting a train,

Pallas Athene in that straight back and arrogant head:

All the Olympians; a thing never known again.

W.B. Yeats

Int en gaires asin tsail

Int en gaires asin tsail

alainn guilbnen as glan gair:

rinn binn buide fir duib druin:

cas cor cuirther, guth ind luin.

Anonymous

A bird is calling from the willow

A bird is calling from the willow

with lovely beak, a clean call.

Sweet yellow tip; he is black and strong.

It is doing a dance, the blackbird’s song.

Translation by Thomas Kinsella

Untitled

The brain is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will include

With ease, and you beside.

The brain is deeper than the sea,

For, hold them, blue to blue,

The one the other will absorb,

As sponges, buckets do.

The brain is just the weight of God,

For, lift them, pound for pound,

And they will differ, if they do,

As syllable from sound.

Emily Dickinson

Talking in Bed

Talking in bed ought to be easiest,

Lying together there goes back so far,

An emblem of two people being honest.

Yet more and more time passes silently.

Outside, the wind’s incomplete unrest

Builds and disperses clouds about the sky,

And dark towns heap up on the horizon.

None of this cares for us. Nothing shows why

At this unique distance from isolation

It becomes still more difficult to find

Words at once true and kind,

Or not untrue and not unkind.

Philip Larkin

Gaineamh shúraic

A chroí, ná lig dom is mé ag dul a chodladh

titim isteach sa phluais dhorcha.

Tá eagla orm roimh an ngaineamh shúraic,

roimh na cuasa scamhaite amach ag uisce,

áiteanna ina luíonn móin faoin dtalamh.

Thíos ann tá giúis is bogdéil ársa;

tá cnámha na bhFiann ’na luí go sámh ann

a gclaimhte gan mheirg—is cailín báite,

rópa cnáibe ar a muinéal tairrice.

Tá sé anois ina lag trá rabharta,

tá gealach lán is trá mhór ann,

is anocht nuair a chaithfead mo shúile a dhúnadh

bíodh talamh slán, bíodh gaineamh chruaidh romham.

Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill

Quicksand

My love, don’t let me, going to sleep

fall into the dark cave.

I fear the sucking sand

I fear the eager hollows in the water,

places with bogholes underground.

Down there there’s ancient wood and bogdeal:

the Fianna’s bones are there at rest

with rustless swords—and a drowned girl,

a noose around her neck.

Now there is a weak ebb-tide:

the moon is full, the sea will leave the land

and tonight when I close my eyes

let there be terra firma, let there be hard sand.

Translation by Michael Hartnett

Sic Vita

Like to the falling of a star,

Or as the flights of eagles are,

Or like the fresh spring’s gaudy hue,

Or silver drops of morning dew,

Or like a wind that chafes the flood,

Or bubbles which on water stood:

Even such is man, whose borrowed light

Is straight called in, and paid to night.

The wind blows out, the bubble dies;

The spring entombed in autumn lies;

The dew dries up, the star is shot;

The flight is past: and man forgot.

Henry King