9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

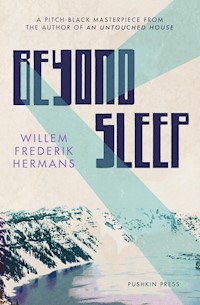

A blackly comic classic from the author of An Untouched House A young geologist hungry for fame journeys to the mountains of Norway's Arctic north on a research expedition, but soon realizes he's more likely be eaten alive by mosquitoes than win glory. Freezing, wet and plagued by insomnia, Alfred becomes increasingly desperate and paranoid under the midnight sun, until he takes a catastrophic decision. This dazzlingly dark classic is at once a gripping survival story, a mordant farce and a peerless evocation of mental disintegration.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

pushkin press

Beyond Sleep

Praise for W.F. Hermans and Beyond Sleep

‘One of the most important European authors of the second half of the twentieth century’

cees nooteboom

‘In Ina Rilke’s lively and graceful translation, Hermans’ novel does what so few do: it makes one see and feel life afresh’

paul binding,Independent

‘As bright and black as anything contemporary. It has the energy and ruthlessness of farce and a terrifying deadpan style, and it ends in appalling catastrophe’

Bookforum

‘Successful and entertaining… A master at work, with a fine, light touch’

The Complete Review

‘Bleak, hilarious, angry, ruthless and plain. [Hermans is] as alarming as a snake in the bread bin. He’s also hugely entertaining’

Scotsman

3

Willem Frederik Hermans

Beyond Sleep

TRANSLATED FROM THE DUTCH BY

Ina Rilke

PUSHKIN PRESS

v

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

Isaac Newton

CONTENTS

1

The porter is disabled.

The oak reception desk at which he sits, staring through cheap sunglasses, is bare but for a telephone. His left ear must have been ripped off in the explosion that caused his disfigurement, or possibly it was burnt in a plane crash. What is left of the ear resembles a misshapen navel and offers no support for the hook of his dark glasses.

‘Professor Nummedal, please. I have an appointment with him.’

‘Good day, sir. I don’t know if Professor Nummedal is in.’

His English sounds slow, as if it’s German. He falls silent, doesn’t stir.

‘I made an appointment yesterday with Professor Nummedal’s secretary – for ten thirty today.’

Automatically I glance at my watch, which I adjusted to Norwegian summer time upon arrival in Oslo yesterday. Half past ten.

Only now do I notice the electric clock above his head, also indicating half past ten.

As if wanting to dispel every vestige of doubt in the disabled porter’s mind, I bring out the letter given to me by Professor Sibbelee in Amsterdam and say: 2

‘Actually, the date was fixed some time ago.’

The letter is from Nummedal to Sibbelee, mentioning today, Friday 15th, as a possible date for a meeting. I wish your pupil a good journey to Oslo. Signed: Ørnulf Nummedal.

I unfold the letter and hold it out for the porter to read. But he doesn’t move his head, only his hands.

On his left hand the fingers are missing, and all that remains on the right is a nail-less stump and the thumb. The thumb is completely unscathed, with a clean, well-kept nail. It almost looks alien to him. Not one finger left for a wedding ring.

His wristwatch has a small metal cover, which he snaps open with his thumbnail. There is no glass beneath the lid.

The porter runs the nail-less stump over the dial and says:

‘It is possible that Professor Nummedal is in his study. Two flights up and second door on your right.’

Open-mouthed, I put the letter back in my pocket.

‘Thank you.’

Why I thanked him I don’t know. The cheek! Treating me as if I were just anyone, someone who’d wandered in off the street without having an appointment.

But I suppress my rage. I’m prepared to have pity on him, like his employer, who evidently sees fit to keep him on despite his inability to perform simple tasks, such as receiving visitors without treating them as though they can drop dead for all he cares.

In the meantime I have counted the treads on the two flights of stairs: twenty-eight each with an interval of eight paces across the landing. From the top of the stairs to the second door on the right is another fifteen paces. 3

I knock. From inside a voice calls something I don’t understand. I push open the door, rehearsing my English phrases under my breath: Are you Professor Nummedal … Have I the pleasure … My name is …

… Where are you, Professor Nummedal?

The study is a vast oak-panelled room. My eyes seek out the professor and locate him in the farthest corner, behind a desk. I advance between two tables laden with half-furled maps. To the side of the small grey figure behind the desk looms the white rectangle of a drawing board in upright position.

‘Are you Professor Nummedal?’

‘Yes?’

He makes a half-hearted attempt to rise.

A shaft of sunlight falls on his spectacles, which are so thick as to appear opaque. He raises his hand to flip up the extra pair of lenses hinged along the top of the frame. Four small round mirrors are now trained on me.

I step up close to his desk and explain that I telephoned his secretary yesterday and that she told me to be here today at this hour.

‘My secretary?’

His English is very hard to distinguish from Norwegian, which I don’t speak, and his voice is as ancient as only a voice can be that has said all there is to say:

‘I do not recall my secretary saying this to me, but perhaps it was her intention. Where does you come from?’

‘From the Netherlands. I’m that student of Professor Sibbelee’s. I’m going to Finnmark with your students Arne Jordal and Qvigstad.’ 4

My hand reaches into my inside pocket and once more draws out the letter Nummedal wrote to Sibbelee.

I find myself unfolding the letter, as I did for the porter.

‘Well, well. You is a Nedherlander, you is …’

I chuckle by way of assent and also to show my appreciation for his near-perfect pronunciation of the Dutch word.

‘Nedherlanders!’ he goes on. ‘Clever people. Very clever. Can you follow me? Or do you prefer to speak German?’

‘It is … all the same to me,’ I say.

‘Niederländer,’ he retorts in German, ‘a highly intelligent nation, they speak all languages. Professor Sibbelee writes to me in a mixture of Norwegian, Danish and Swedish. We call that Scandinavian. Take a seat.’

‘Thank you,’ I say, in English.

He sticks to German.

‘I have known Professor Sibbelee for many years. Let me see, when did I first meet him? It must have been before the war, at the conference in Tokyo. Yes. The year I presented my paper – which has become a classic, if I may say so – on the milonite zone in Värmland and its expansion into Norway. Vielleicht kennen Sie die kleine Arbeit?’

He pauses for a moment, but not long enough to compel me to confess my ignorance of the said opus. Then, brightly, he continues.

‘Sibbelee opened a debate about it at the time. Things got quite heated. He could not agree with a single argument I put forward. Can you imagine? Such a to-do! Sibbelee is thirty years younger than me and in those days he was very young indeed, very young. The passion of youth!’

Nummedal bursts out laughing. Even when he laughs the creases in the far too ample skin on his face remain for the most part vertical. 5

I laugh along with him, although I’m a bit concerned about his memories of the very person who recommended me to him.

Can he see what I’m thinking?

‘Das sind jetzt natürlich alles alte Sachen! All water under the bridge, now. Sibbelee changed his tune eventually. He even worked here at my institute for a spell. I can’t for the life of me remember what sort of research he was engaged in. One can’t remember everything. In any case, he spent quite some time here. The results didn’t amount to much, as far as I know.’

Exit Sibbelee, down the hatch. I can sense my mentor’s nemesis rubbing off on me. Wouldn’t it be better to take my leave now? But the aerial photographs?

‘I am eighty-four years old,’ Nummedal says. ‘I have seen a great deal of scientific work done to no avail. Warehouses filled with collections no-one takes any notice of, until the day they are thrown out for lack of space. I have seen theories come and go like wild geese or swallows. Have you ever eaten braised lark? Incidentally, there is a restaurant here in Oslo where they serve gravlachs. Have you heard of it? A sort of salmon, not like smoked salmon – well there is a similarity I suppose, but more delicate, more subtle. Raw salmon, buried underground for a time and then dug up again.’

His voice has grown more subtle, too, to the point of being inaudible. The skin of his neck droops slackly in his too-wide collar, and when he purses his lips in deep thought the folds seem to travel upwards, unimpeded by his chin, to corrugate his whole face.

6Silence.

On the desktop before him are papers and two large stones. Also some small porcelain bowls containing smaller stones dusted with cigar ash. Across the papers lies a magnifying glass the size of a frying pan.

‘Professor Sibbelee asked me to pass on his best regards to you.’ ‘Thank you, thank you.’

Another silence.

My tongue is a hand groping in the depths of a black sack for some way of steering this conversation to my purpose in coming here. Nothing tactful comes to mind. Plunge in at the deep end, then.

‘Did you, by any chance, manage to get hold of those aerial photographs for me?’

‘Aerial photos? What do you mean, aerial photos? Of course we have aerial photos here. But I do not know whether anyone is using them at present. There are so many aerial photos.’

He doesn’t know what I am talking about! Could he have forgotten his promise to Sibbelee, that he would give me the aerial surveys I need for my fieldwork? I have a feeling that further explanations of my need will be counterproductive, but I can’t think of anything better. I can hardly give up without having tried every tack.

‘Yes, Professor, the aerial photographs …’

‘Is it the entire collection you wish to see?’

‘There has been … there was …’ 7

My left hand is down between my knees holding my right, which is bunched into a fist. My elbows press against my sides.

‘There was mention of a set of aerial photographs I could use for my research in Finnmark.’

I am not sure what I just said rates as correct German, but I can’t imagine there was anything Nummedal would have any difficulty understanding, and I articulated the words clearly and without faltering.

He draws a deep breath and says:

‘I consider Qvigstad and Jordal among the best pupils I have ever had, and I speak of a period of many years, you understand. They know all about Finnmark.’

‘Of course. I have only met Qvigstad briefly, but Arne strikes me as someone from whom I can learn a great deal, which makes it all the more a privilege for me to accompany him.’

‘A privilege, sir? Indeed it is! Geology is a science that is strongly bound to geographic circumstance. In order to obtain results that amaze and impress, one must practise geology in areas with something left to discover. But that is the great difficulty facing us. I know a fair few geologists who went looking in places where no-one had bothered to look before because it was assumed there was nothing there. They never found anything either.

‘May I let you in on a secret?’ he goes on. ‘The true geologist never completely forsakes his gold-prospecting forebears. You may laugh at me for saying this, but I am old. Which gives me a certain right to romanticise.’

‘No, no! I know exactly what you mean!’

‘Ah, so you know what I mean. But for you as a Dutchman, the concept must be somewhat unpalatable. Such a small 8country, densely populated for centuries and with scientific standards known to be among the highest in the world. I can well imagine the geologists in Holland having to stand on each other’s toes, and being sorely tempted in the process to palm off a stray toe as the incisor of a Cave Bear!’

‘The country is small, admittedly, but the soil is exceptionally varied.’

‘That is what you people think, just because there is a geologist with a microscope on each square metre. That does not change the fact that there are no mountains. No plateaux, no glaciers, no waterfalls either! Marshland, mud and clay, that is all! It will end with them counting every single grain of sand, I shouldn’t wonder. To me that is not geology. I call it bookkeeping, hair-splitting. Verfallene Wissenschaft, is what I call it, verfallene Wissenschaft.’

My laughter is both civil and sincere.

‘Oh, Professor, they have also found coal, salt, oil and natural gas.’

‘But the important issues, my dear sir. The big questions! Where did our planet come from? What is its future? Are we heading towards a new ice age, or will there be date palms growing on the South Pole one day? The big questions that make science great, the questions that are the true function of science!’

Pressing both hands on the creaky desktop, he rises.

‘The true function of science! Do you understand? Coal to burn in the stove, natural gas to boil an egg for breakfast, salt to sprinkle on it – mere household words, as far as I’m concerned. What is science? Science is the titanic endeavour of the human intellect to break out of its cosmic isolation through understanding!’

2

Nummedal comes out from behind his desk. He keeps his fingertips in contact with the desktop throughout.

‘I propose taking you on a little tour of the environs of Oslo this afternoon. Where are those maps …?’

He moves towards one of the long tables covered in maps.

‘That would be very nice,’ I say.

I spoke without emphasis or reflection.

What if I had said I had to continue my journey northwards this afternoon?

He flips down his extra glasses and holds one of the maps up close to his eyes. What if I come right out and tell him the only reason I called on him was to get hold of the aerial photographs?

His jaw sags.

What if I tell him I’ve already booked a seat on the plane to Trondheim? That I must leave in fifteen minutes?

But what if he takes offence, and lets me go off to Finnmark without the photographs?

I step closer to him. We stand side by side at the long table. The map in his hands has been rolled up for a long time, the corners curl inwards. Nummedal leans forward to spread it out on the table and I help him hold down the springy paper. 10It is a heliotype print. Could it be an unpublished map, one he has picked out as a special favour to me?

No, it is an ordinary geological survey of the Oslo district. He says:

‘I must have a better copy somewhere, in colour.’

As he moves down the table he upsets a pile of papers, spilling them across the floor. I squat on my heels to retrieve them.

‘Oh, there is no need!’

Looking up, I see he’s holding another map, a cloth-backed one this time. With my hands full of papers, I straighten up. Nummedal takes no notice.

‘Here it is. Come along now, let’s go.’

I lay the papers on the table and follow him.

Which map has he got now? While I hold the door open for him, I see it is the coloured version of the geological survey of Oslo. Does he really have no idea why I am here?

‘This one is mounted on linen,’ he says, ‘but not in the proper way. It can’t be folded.’

And he hands me the map.

The corridor. We move towards the stairs, me on his left with the roll under my arm.

‘I was in Amsterdam before the war,’ Nummedal says, ‘I visited the geological institute there. Splendid building. Fine collections from Indonesia.’

His right hand trails along the wall.

‘Losing the colonies must have been a terrible blow for geologists in your country.’

‘It would seem so on the face of it. But fortunately there are plenty of opportunities elsewhere.’ 11

‘Elsewhere? My dear young man, don’t delude yourself! Other countries have their own geologists. The science is bound to suffer in the long run if your geologists have no alternative but to set their sights abroad.’

The thirteenth tread of the second flight down.

‘Maybe,’ I say. ‘Still, you know, nowadays, with all the new international organisations, and borders becoming so much easier to cross …’

‘All that looks fine on paper! But where does it leave the profound insights and natural affinity with the big questions, if people receive their training in a tiny, flat country of mud and clay without a single mountain?’

Just as well he doesn’t expect an answer.

‘You must admit,’ he explains, unprompted by me, ‘that tectonics is the branch of geology par excellence with scope for mental constructs of genius. Is there anything more challenging than drawing inferences about the interior structure of the Alps or the composition of the Scandinavian Shield from a handful of observations and measurements?’

We have not reached the bottom of the stairs, but he halts anyway.

‘In a place like Holland you never have solid rock underfoot! When you arrive in Holland what is the first thing you see? The control tower at the airport with a sign saying: Aerodrome level thirteen feet below sea level. What a welcome!’

Laughing, he completes his descent, but once more pauses in the hall.

‘You would think the floods of 1953 had taught them a lesson. Other people would have left, they would have moved 12beyond the reach of the sea! But not the Dutch! Where could they go, anyway?

‘Sir, I will say this: if an entire population specialises itself, generation upon generation, in surviving in a country that is strictly speaking the domain of fish, then those people will end up inventing a special philosophy of their own, in which the human dimension is totally lacking! A philosophy based exclusively on self-preservation. A world view that amounts to keeping dry and making sure there’s nothing fishy going on! How can such a philosophy be universally valid? Where does that leave the big questions?’

Interjections come to mind: what good did universally valid philosophies ever do anyone? What are the big questions anyway? Isn’t survival a big question in a world fraught with danger? But the prospect of having to say all this in German is too daunting,

The clock in the vestibule indicates five past midday and the porter is nowhere to be seen.

Nummedal goes over to the reception desk, rests his hand on the top and sidles towards a cupboard, which he opens.

He takes out a walking stick and a hat. The stick is white with a red band beneath the handle.

Blind boss of a blind porter.

3

Out in the street I feel like a dutiful grandson accompanying his half-blind grandfather on a stroll because it’s such a sunny day.

But it is he who draws me to the restaurant.

It’s a large, posh restaurant. Or was. Now there are pink plastic chairs and small tables without tablecloths. The walls are panelled with hardboard in pastel shades, teak-finish chipboard and formica with perforations.

There are no waiters to be seen, just girls collecting dirty dishes.

Background music: ‘Skating in Central Park’ from the Modern Jazz Quartet.

I steer Nummedal carefully between the tables and chairs to the long counter.

I take two teakwood trays and place them end to end on the nickel-plated bars along the front of the counter. Nummedal is by my side, his white stick hanging on his arm. The stick swings in front of my face with each wave of Nummedal’s arm to attract the attention of the staff behind the counter. A whole row of scrubbed blondes wearing green linen tiaras.

Nummedal and I are in a queue of hungry customers, all of whom slide their teak trays along as they load them with 14dishes from the counter. But Nummedal is so agitated that he forgets to move on, causing a pile-up behind him. He makes a baying sound from time to time. Frøken!

Frøken!

Not one Frøken takes any notice. The Frøkens are busy replenishing the servings on the counter. Frøken hors d’oeuvre pretends not to hear, Frøken bread rolls ditto, Frøken soup isn’t listening, nor is Frøken meats.

What does Nummedal want, anyway?

Why does he need assistance? Why can’t he take his pick from what’s available? And if he can’t see properly, why doesn’t he tell me what to get for him?

My poor senile grandfather making a fuss over nothing. Nummedal … his name reminds me of the old Dutch word for ‘nothing’. Could that be what his name means?

Now and then I give his tray a nudge with the side of mine. We are reaching the desserts and still haven’t picked anything to eat. We’ll have to go back to the end of the queue if we’re not careful, and shuffle past the counter all over again. I haven’t dared to put anything on my tray, not even a glass, knife, fork or paper napkin.

At one point Nummedal refuses to budge at all, causing a gap in the line. Shall I help myself to a portion of pineapple and whipped cream, just for something to do? The people ahead of Nummedal have already gone past the cash register. I look round anxiously in case we’re causing a disturbance among the hungry patrons. No lamentations from them, not even a sigh. Dapper Vikings! Noble race of unhurried giants! Nummedal is still baying.

I can now make out a second word: gravlachs!

*

15The girl in charge of the pineapple and whipped cream has heard it too. She leans forward to Nummedal, shakes her head, draws herself up again and calls back to the girls we have already gone past.

The word has also been heard on the customer side of the counter. Everyone starts looking for gravlachs. They’re still in the throes of selecting, inspecting and sniffing when the word gravlachs returns to the whipped-cream Frøken after passing from tiara to tiara. It is now presented in the negative.

Nummedal exclaims loudly, thankful that his question has been understood, apologetic about placing an impossible order.

‘No gravlachs in this place!’ he declares in English.

‘I understand. It’s not important.’

Next he apologises for not having spoken to me in German, and repeats: ‘Kein gravlachs hier!’

‘Ich verstehe, ich verstehe,’ I say.

Quickly I seize a bowl of pudding and set it on my tray. Arriving at the cash register I see mugs of hot coffee. Nummedal has left his tray behind, he has taken the coffees and is now paying for both of us, without checking his change.

A man leaves the queue and approaches me. His head is square and his spectacles are perfectly round. He points to the furled geological map tucked under my arm. He smiles and makes a little bow.

‘I understand you are a stranger here … This is a very bad restaurant, you know, where they don’t have gravlachs. In Oslo one can never find what a foreign visitor wants! I am ashamed of my native city. You must be accustomed to so much better in London. But you have a map, I see? Is it of the city? May I take a look?’ 16

Balancing the tray on my left hand, I reach for the map with my right and pass it to him. He’s going to have to wait in line again, just because he wanted to help.

He unrolls the map.

‘There is only one restaurant where you can get gravlachs. I will point it out to you.’

‘Won’t that be too difficult on this map?’

It’s on the tip of my tongue to tell him it’s a geological survey. What will he think when he sees all that red, green and yellow, with the city itself no bigger than a potato sliced in half?

His finger is poised to trace the direction. The map springs back, I want to be of assistance, the tray balancing on my hand teeters.

It teeters in his direction. The coffee spills over him in a tidal wave, the pudding clings in evil little clots to his suit, the bowl shatters on the floor, but I manage to keep the tray from falling. He holds the map aloft with outstretched arms. I look round to see where Nummedal has got to. He’s seated at one of the tables, stirring his coffee.

‘No harm done! No harm done!’ cries the man who wanted to help, waving the bone-dry, unsullied map.

I take the map from him. Pushing me out of the way, two waitresses set about wiping him down with a sponge and a towel.

More helpful Norwegians gather round.

One of them has fetched a pudding for me, another coffee, and a third brings a salad with pinkish slivers of fish.

‘Lachs, lachs!’ he singsongs. ‘Lachs, lachs! But no gravlachs! Too bad!’

I ask how much I owe them, looking from one to the next, get no reply. I try again, but stammer so badly that their pity 17only increases. Can’t speak a single foreign language, they reckon. Came all the way from God knows where to eat gravlachs.

Hoping and praying they won’t come after me, I turn my back on them and take the loaded tray to the table occupied by Nummedal.

A Frøken kneels on the floor to mop up the spilled pudding.

Nummedal says: ‘Haben Sie die Karte?

I spread the map on the table, taking deep breaths in anticipation of the next ordeal.

Nummedal pushes his spectacles up on his forehead, fumbles under his clothes and draws out a magnifying glass on the end of a black cord. He holds the glass just above the map, as though searching for a flea. He cranes his neck as far as it will go. His head looks ready to come loose and roll over the table. Muttering, he slides the magnifying glass with one hand while trying to point with the other. The map curls up maddeningly. I make myself useful by securing the corners with the ashtray, one of the mugs and my two dishes. But I’m not listening.

Had I been taught by private tutors all my life, I would be illiterate today. Never have I been able to concentrate when people start explaining things to me on a one-to-one basis.

Ever seen the heart of an animal cut open while still alive? The malevolent pulsating within the splayed monstrosity?

That’s how it is for me when I have to listen to someone explaining something – a sense of time being pumped through empty space. Almost suffocating, I gasp: Yes, yes. Sitting still is an enormous effort, as exhausting as a three-day hike.

*

18Nummedal is showering me with information I didn’t ask for. I need his aerial photographs, not his vanity. Beads of sweat trickle down my breastbone, which begins to itch; my eyes goggle out of my head. I see and hear all, but don’t register.

May queens appear behind the counter wearing burning candles in their hair.

With open-heart cleavage, the Frøken mops up the mess I made on the floor. Her honey hills, her beehives.

I curl my lips away from my teeth and slowly open and close my jaws.

Nummedal has found some detail on the map which he considers of paramount importance to me.

He puts down his magnifying glass, takes off his spectacles, pulls a white handkerchief from his trousers and begins to polish each of the four lenses in turn. In the meantime he preambles:

‘In fact the Oslo district extends from Langsundsfjord in the south, which you can’t see here, up to Lake Mjøsa in the north …

‘Tectonics …

‘Deposit of the Lower Palaeozoic … Drammen … Caledonides … Archean substratum … two synclinals … litho-tectonic structure … shale …’

I make noises, bend over the map so closely that I can distinguish neither dots nor lines, say:

‘Yes, yes!’

And exclaim:

‘Of course!’

But I’m close to exploding with despair at not even catching enough of Nummedal’s exposé to be able, later on, when he points everything out to me in the field, to tell him how right he is. 19

Then at least he might form a more favourable impression of me than of my mentor Sibbelee … and give me the aerial photographs, which is all I want from him.

‘Are you really going to show me all that? Won’t it be too much trouble?’

‘Being in Oslo and not even taking a look around the Oslo district! Out of the question.’

‘I am very grateful for your …’

‘Ja ja, schön! That is what all you young people say! Shall we go now? I have finished my coffee.’

But I haven’t. Out of feigned respect I haven’t touched my food. I stuff my mouth full of salmon and pass Nummedal his white stick. He walks off, unsurprisingly leaving the map behind for me to carry.

At the exit the man who wanted to help comes up to me again.

‘Gravlachs!’ he cries. ‘There is only one restaurant where you can get it, but it is closed in June. No gravlachs in the whole city! I do apologise. You are not used to this in London. Or are you from New York? This is typically Norwegian! They never get anything right here! This would never have happened in Paris. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. No alcohol in restaurants. No striptease either! Good luck to you, sir!’

4

The asphalt rises and falls. There are few cars about and the pavements of Oslo are lined with grassy ramps.

A white, columned palace in the distance where the king resides.

Down a flight of steps. Underground station. Electric train.

One of the oldest electric railways in the world, supposedly, with carriages made of vertical oak planks, varnished and meticulously secured with brass screws.

Nummedal and I sit facing each other at a small window. The tunnel is quite short, and soon we are riding in the open. The track is carved out of rock. The train gives a high-pitched hum in the bends as it snakes upwards.

The city lies below.

Nummedal has stopped talking, and I rack my brains for something to say.

Everything that comes to mind is unspeakable: … how is it possible that you, all of eighty-four years old, can still be lording it over a university lab … what a diehard you must be … entitled to your pension for at least ten years if not twenty … assuming the retirement age in Norway is sixty-five, although it might be sixty given that the socialists have been in power for such a long time … but 21he chose to remain at his post, loyal and irreplaceable … rules have no doubt been bent to make this possible … the incomparable Nummedal! … I wonder how long he has been practically blind? … Honorary doctorates in Ireland, Kentucky, New Zealand, Liberia, Liechtenstein, Tilburg. Praiseworthy, indefatigable in old age … enviably so … or such a harridan of a wife at home that heaven and earth must be moved to spare him the blessings of otium cum dignitate in her company … or else some sourpuss housekeeper …

I consider his clothing … old, but neat. Old people wear out faster than their clothes. Why is that? He has on a type of ankle-boots you’d be hard pressed to find in the shops nowadays. Sturdily re-soled. A fastidious type.

I reckon he designed his glasses himself. Had them made in the instrument workshop of the university, of course. I feel a sudden rush of pity … I’d like to say to him with tears in my eyes: Listen here, Nummedal, Ørnulf. I know what you think, but you’re mistaken. There is no hereafter presided over by some little old man even older than you, with all the honorary doctorates and all the same principles, albeit on a more exalted level. Once you take the big step into the utter darkness that might fall any moment – a stroke, for instance, causing a flash flood in your decrepit brain – there won’t be a little old man saying: Hello, Ørnulf, it has been my pleasure to see how you got on over the years, how you stuck to the university instead of taking things easy at home, how you received a preannounced visitor from abroad with a mixture of arrogance, irony and bonhomie. And how you took him to the mountains to show him you’re not past it yet, so he can tell the folks back home: Nummedal’s still going strong. 22Tough as old boots. Could still teach every young man a thing or two!

He swings one leg over the other. His liver-spotted hands rest on the handle of his white stick, swaying from side to side with the cadence of the train.

‘Judging by the time,’ the geologist-cum-Adenauer-lookalike says, ‘we should soon be going past an area where the Silurian is clearly exposed. Keep your eyes peeled. You can’t miss it if you’re careful. Look, over there.’

He points to the wooden slats between the windows, but I can distinguish the Silurian rock anyway.

My thoughts begin to drift again. What do I want? I want him to give me the aerial photographs … How am I to get through to this very old man, who’s long past caring what anyone might have to say and who feels no compunction at putting people in an impossible position, assuming he still knows what he’s doing?

Perhaps it’s Sibbelee who is most to blame. Sibbelee should have presented my case differently. Should have said … well, what? He should have asked for the photographs to be sent to Holland! But Sibbelee was not to know precisely which aerial photographs exist of the terrain I am planning to write my thesis on. Besides, wasn’t it a mark of courtesy on my part to collect them in person?

Suddenly it hits me where I went wrong!

I should have fallen to my knees upon entering Nummedal’s study. Humble, but eloquent! Help me, I should have cried, sate me with knowledge! I shall write ten scientific articles and make sure your name occurs a hundred times in each! I shall mention your name in everything I publish to the end of my days, even if the subject has nothing 23whatsoever to do with you or your invaluable research. I have friends on advisory committees for honours lists … honorary doctorates … obituaries …

Obituaries??

But it’s too late now anyway … I have let the perfect opportunity for attack pass, and now I am under siege. Cowering on the defensive, stuck fast like a warped axle in a damaged hub.

In a fix I can’t squirm out of.

5

Nummedal is an excellent walker.

Out here, in the bright sunshine, his eyesight seems a lot better, too.

We climb higher and higher, and Nummedal takes every available short cut between hairpin bends, striking up footpaths sloping at close on thirty degrees. His pace is steady, his breathing unlaboured, and he holds forth on geological subjects as he climbs.

At appropriate moments I respond with affirmative grunts. I can tell from his intonation when is a good time to come out with an ‘of course’, ‘quite so’, ‘of course not’, or even the occasional ‘ha ha!’.

I am still carrying the rolled-up map. Each of my arms aches in turn, after ever shorter intervals, as I have to keep the arm securing the map from pressing against my side to avoid creasing it. Now and then I hold it at one end between thumb and forefinger, but when I do that I can’t let my arm hang down because the map would trail on the ground. I lag behind Nummedal and hold the map to my eye like a spyglass. Have to stop myself using it as a trumpet. Oh God! What misery, I would wail.

The mountainside is interrupted by a small plateau. Here a tall ski tower has been erected, from which a wooden slide protrudes like a tongue made of logs. We go inside, climb 25up countless steps, and arrive at last on a platform with parents and children leaning over the parapet admiring the views.

The tower is situated near the tip of the fjord. You can see nearly all of it from this height, with the sprawl of the city on the left and dark forests on the right.

‘Und geben Sie mir jetzt die Karte!’

I unroll the map. He flips up his extra lenses. Points. Flips the extra lenses down again. Speaks. Taps on the map with the back of a pencil. Points into the distance again. He’s giving a lecture. I dare say he’s been coming here with his students these last sixty years.

There’s a French saying: not knowing which leg to dance on.

I don’t know which leg to stand on.

I lose all grip on my thoughts: like birds fleeing a cage when the door is left ajar, they take wing into the landscape.

The fjord is deep blue, while the blue of the sky so far north seems almost too timid to call itself blue. Craggy mountains, toy-town houses. A world-famous panorama. Seeing this and dying – by whooshing down the slide made of logs, which stops abruptly above a round lake. In winter the slide is covered in snow, of course, and the lake frozen over. How many times do I whoosh down, ski-less, snow-less, while Nummedal pontificates? If only he’d given me the photographs – how happy I’d be to listen to his every word, how enchanted by the wonderful scenery.

When finally he comes to the end of his lecture I see that the map has been the wrong way up all along.