Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

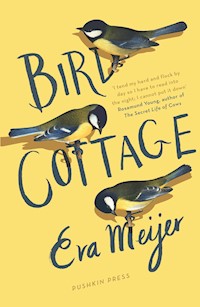

A novel based on the life story of a remarkable woman, her lifelong relationship with birds and the joy she drew from it I want to find out how they behave when they're free. Len Howard was forty years old when she decided to leave her London life and loves behind, retire to the English countryside and devote the rest of her days to her one true passion: birds. Moving to a small cottage in Sussex, she wrote two bestselling books, astonishing the world with her observations on the tits, robins, sparrows and other birds that lived nearby, flew freely in and out of her windows, and would even perch on her shoulder as she typed. This moving novel imagines the story of this remarkable woman's decision to defy society's expectations, and the joy she drew from her extraordinary relationship with the natural world. Eva Meijer is a Dutch author, artist, singer, songwriter and philosopher. Her non-fiction study on animal Communication, Animal Languages, is forthcoming in English in 2019. Bird Cottage is her first novel to be translated into English, has been nominated for the BNG and Libris prizes in the Netherlands and is being translated into several languages. Eva Meijer was awarded the Halewijn Prize in 2017 for all of the books she has written so far.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

1965

Jacob flies swiftly into the house, calls to me, and then immediately flies out again. He rarely makes a fuss about things, and never flies very far from the nest once his babies have hatched. He usually visits the bird table a few times in the morning, and then stays close to the wooden nesting box on the birch tree. He is a placid bird, large for a Great Tit, and a good father.

I follow him out of doors and hear the machine even before I’ve left the garden. I run clumsily on clogs that almost slip off my feet. No. This can’t be happening. Not that hedge. Not in the springtime. But a stocky man is trimming the hedge with one of those electric hedge-cutter things. He can’t hear me through the racket. I squeeze between the hedge and the machine. The noise drowns out everything, crashing in waves over me, boring through my body.

It gives him a shock to see me there, suddenly in front of him. He switches the thing off and removes his ear-protectors. “What’s up, missus?”

“You mustn’t trim this hedge. It’s full of nests. Most of the eggs have already hatched.” My voice is shriller than usual. It feels as if someone is strangling me.

“You’ll have to speak to the Council about it.” He turns the machine on again.

No. Twigs jab at my back. I move to the left when he moves, and then to the right.

“Get out of my way, please.”

“If you want to trim this hedge, you’ll have to get rid of me first.”

He sighs. “I’ll start work on the other side, then.” He holds the contraption at the ready, more as a shield than a weapon.

But that’s where the Thrushes are, with their brown-speckled breasts. I shake my head. “No. You really mustn’t.”

“Look, missus, I’m just doing my job.”

“What is your boss’s phone number?”

He gives me a name and the County Council number. I keep an eye on him until he has left the lane. He’s probably off to another hedge now.

Cheeping and chirping everywhere. The parent birds are nowhere to be seen, but the babies make their presence known. The parents will return and with any luck they won’t have had too great a shock. I hurry to the house, sweat running down my back. I don’t even pause to take off my cardigan.

“May I speak to Mr Everitt, please? It’s urgent.”

While I’m waiting for him, Terra comes and perches beside me. She can always tell when something is wrong. Birds are much more sensitive than we are. I’m still panting a little.

“Mr Everitt, I appreciate your coming to the telephone. Len Howard speaking, from Ditchling. This morning I discovered, to my great horror, that one of your workmen was trimming the hedges. It’s the nesting season! I’m making a study of these birds. My research will be ruined.”

Mr Everitt says I have to send in a written request to have the hedge-cutting postponed so that the Council can decide on the matter. He can’t make that decision himself. I thank him very much and ask for a guarantee that there’ll be no further hedge-trimming till then.

“I’ll try my best,” he says. “They do usually listen to me.” He coughs, like a smoker.

I know the Great Tits would immediately warn me if they came back to trim the hedges, but for the rest of the day I feel very agitated. Sometimes the wind sounds like hedge-trimming; sometimes I’m tricked by a car in the distance. Jacob also remains restless. And that’s not like him at all. He’s old enough—at least six—to know better.

I start writing my letter. They must listen to me.

* * *

Early the next morning I make a trip into the village. It is the first really warm day of the year. The air seems to press me down, deeper into the road. My body is too heavy really, always getting heavier. In the past it used to take me ten minutes to walk there, but now the journey takes almost twenty. I rap on the grocer’s window. It isn’t nine o’clock yet. “Theo?” I knock again and spot his tousled white head of hair moving behind the counter. He stands up and raises his hand. In greeting? Or as a signal for me to wait a while?

Rummaging noises, the sound of metal on metal.

“Gwendolen! What brings you here so early?” Sleep still lingers in his face, tracing lines as fine as spider silk.

I tell him that the Council is planning to have the hedge trimmed and show him my letter. “Will you sign it too?”

He puts on his spectacles, carefully reads what I’ve written, then searches in three different drawers for a pen. “Esther was serving in the shop yesterday. Everything’s in a muddle. A moment ago I couldn’t find the key to the front door.”

“How is Esther?”

“She’s saving up for a scooter. Her parents aren’t at all keen, but all the lasses have one.” He looks at me over the top of his spectacles and gives a brief shrug.

“Is she sixteen already? Goodness!” I still have the image of her as a little girl, his daughter’s first daughter. A precocious child, with eyes that seemed like openings to another world. Her eyes are still like that, heavily accentuated with kohl.

“Not yet. Next month. Why don’t you leave the letter here, Gwen? Then I can ask all my customers to sign it.”

“Good idea.” We agree that I’ll return for it later in the day. I thank him, pick up my shopping basket, and begin my usual rounds. The baker gives me one of yesterday’s loaves. The butcher has saved some offcuts of bacon. The greengrocer presents me with a bag of old apples. I had thought of going to Brighton today, to the tree nursery, but I decided against it. It’s far too hot to tackle those steep streets. On the way home Jacob comes to say hallo, and I catch sight of the pair of Robins who nested in my garden last year. Perhaps they’re nesting in my neighbour’s garden this year, which would not be very clever. Her cat is a terrible bird-hunter, the worst I know, even worse than the little black cat she had before. Moreover, this cat is very curious and peeks in all the nest boxes, which means that every cat in the neighbourhood knows where they are. I’ve told my neighbour three times now that she is responsible for all the consequent tragedies.

The Great Tits are sunning themselves in the front garden, their wings outspread. Jacob and Monocle II are sitting next to each other, very fraternally, as if they don’t usually spend the whole day quarrelling. It’s the heat that has made them so placid. Terra is on the path. She has positioned herself exactly where I always walk. Jacob’s oldest son is perched on a low, broad branch. He is a little slower than the others—too much feeding at my bird table! Inside, I flop down onto the spindle-backed chair. I’ll have to make the whole journey again soon. Cutie lands on my hair, then immediately flies up, and here comes Buffer. It’s a game the baby birds discover anew, every year. They fly from the cupboard to my head, from my head to the table, from the table to the cupboard, three rapid rounds, then wing their way out of the window, so swift and full of now, only now.

* * *

At the top of the path Jacob comes to warn me. Even before hearing the noises, I know they’re at it again. Since I received the letter from the Council—apologies, absolutely impossible, merely private concerns, important planning considerations—and sent them my objections, I have barely been away from here for almost a fortnight. Yesterday I received a message that the mayor is considering my objections after all, so I thought the danger was over. I walk as swiftly as I can, lame as an old horse. There are three of them this time. Jacob is flying madly back and forth, and so are all the other Great Tits, and the Robins, and the pair of Sparrows.

“There are nests in that hedge,” I cry out, my heart thudding in my throat. But it’s already happened, only the Blackbirds left, perhaps they’ve fledged already, but the baby Robins were still too little.

A carrot-headed young fellow, with collar-length hair and a round, freckled face, takes off his ear-protectors. “’Scuse me?”

“You’ve killed all the baby birds.” I spurt the words out, spraying spittle with them.

He looks at the hedge, eyes squeezed tight against the sun, holds his breath a moment, hesitates. “Sorry.”

“See what you’ve done now.” Jacob is crying out and complaining. The Sparrows are cheeping, calling to the other Sparrows. The Blackbirds are making a terrible crying sound that I’ve never heard from them before.

The young fellow gazes at the Thrushes and the Robins and the Titmice flying back and forth over the hedge, to the field and back again, over the heads of his co-workers, towards me. A cloud passes over his blue eyes. He stops the other two men and points at the Sparrows just across from him. They fall silent and I can hear the birds cry out even louder. They’re calling and calling, exactly as they do when Magpies attack their nests, but this time they don’t stop.

I stay where I am until the men are out of sight. All the birds have deserted the hedge. Only Jacob remains. I call him, offer a peanut. He doesn’t come.

I walk along the hedge looking for nests, to see if there are any babies left behind. I can’t see anyone any more, just little feathers caught among the cut leaves and twigs. At the corner I find a little one that has fallen from its nest. It’s a Sparrow, newly fledged. I carefully lift up the little brown body, already knowing that things aren’t right. The creature trembles and then goes totally still, stiller than any stillness that holds life. With my other hand I make a little hollow in the earth beneath the hedge, lay him gently down, then cover him up.

The silence wraps itself round me, accompanies me home, where the Great Tits are flying around more nervously than normal. I put food on the bird table for them, earlier than I usually do. Perhaps this will distract them—peanuts, bread, some pieces of pear, but nothing fatty because it’s the nesting season.

This late springtime green is still overwhelming, still so brilliant—a luxuriant abundance. I sit down on one of the old garden chairs by the front of the house. My hip seems to want to work itself free from my body. This damned old body.

Terra lands on my shoulder. Her tiny claws prick into the fabric of my blouse. She is so dependent on me, even though she never sleeps indoors. She made her nest in the tall apple tree, thank goodness, not in the hedge. The hedge-cutting didn’t make much of an impression on her—she has enough experience to know that it’s not worth getting too excited. She taps her beak against my shoulder, very lightly, as if she’s trying to remind me of something.

STAR 1

Behaviourism, the theory that dominates all contemporary research into animal behaviour, assumes that scientifically valid data can only be obtained in situations free from extraneous stimuli, in which reactions can be measured in reproducible experiments. The animal mind, which includes the human mind, is viewed as being a kind of black box into which we have no access. From this standpoint, the description of natural behaviour adds little to scientific knowledge since such behaviour cannot objectively be measured. Darwin’s work on animal intelligence, for example, is regarded as unscientific because it is primarily based on anecdotal evidence. Behaviourism, however, does not properly take account of the fact that many animals behave differently in captivity than when they are free. Most birds are timid by nature, actually often afraid of human beings, and when they are kept in laboratories their behaviour and the research results are bound to be affected. Furthermore, any empirical research based on the notion that the thoughts and feelings of animals are unknowable can only produce results that support this picture. If you perceive someone as a machine, then your research questions will reflect that, and will determine the space in which the object of your enquiry can respond. Note well, I have deliberately used the word “object” here. The so-called objective method of studying animals is, therefore, just as coloured by assumptions as any other.

It is now well over ten years since I moved to the little house in Sussex that I would later call Bird Cottage. It is situated on the edge of a small wood and is close to an area of great natural beauty where countless birds and other creatures live: Wood Pigeons and Cuckoos, Foxes and Badgers,Field Mice and Moles, Buzzards and Tawny Owls, Chiffchaffs and Pochards. In the trees and bushes surrounding the house there are also a great number of small birds, such as Blackbirds, Great Tits, Robins and Sparrows. Soon after moving in I set up a bird table on the terrace in front of the cottage, and at seven o’clock each morning and at five in the afternoon I would put out all kinds of titbits for them. I also placed a bird bath there and hung up a few nest boxes: on the house itself, the old oak and the apple tree. It did not take long for the first inquisitive Titmice to come and investigate. The Sparrows immediately chased them off. They will take over any territory if they have the chance. But the Sparrows were more afraid of me than the Tits were, and because I spent a great deal of time observing the birds from the garden bench, all of them had the opportunity to eat the food on the table, and all could inspect the changes that were happening in the house.

I came to live here in February 1938. Most of the birds were already busy looking for places to build their nests and, in some cases, for a suitable mate. They were more interested in each other than in me. In March, however, that began to change. One of the Great Tits, Billy, an older male with a proud bearing and a loud voice, was cheekier than the rest. He was the first to fly each morning to the bird table and every afternoon he would visit the bird bath for an elaborate wash. One warm day in April he flew through the open window and into the house. He fluttered around the sitting room and then rushed swiftly out of the window again. The next day he came once more. One of the ways that Great Tits learn is by watching each other closely, and before very long Billy’s partner, Greenie, came inside with him too. I called her Greenie because of the green sheen on her feathers. From then on I always left the top light of the window open so they could fly in and out as they pleased. This was the start of a very special way of living that has continued to this very day, and has taught me a great deal.

1900

“Look, Lennie.” Papa is holding something in his hands. I run towards him.

“Is it a Titmouse, Papa?”

“It’s a Blue Tit. He’s fallen from his nest. I found him under one of the beech trees, by the girls’ school. Or rather, Peter found him.” Peter wags his tail at the sound of his name. “Now, you keep hold of him for a moment, and I’ll find a box to put him in.”

Its little feathers! I’ve never felt anything so soft in all my life. I shape my hands into a little bowl, a small nest, and lift them to my mouth. I give the birdie a light kiss. So soft! So blue, that tiny head! The creature stirs, shivers a little. It startles me, but I hold my hands firmly together.

“Put him in here. Very carefully.” Papa has brought a cardboard box from his study, with an old scarf lining the bottom.

I gently lower my cupped hands till they touch the bottom of the box, then slowly pull them apart.

“Well done. And now we’ll go and buy him some food.” He takes me by the hand. Olive and Kings and Duddie all go to school and Mama won’t let me go there yet, but now I’m in luck. At last, I’m the lucky one!

“Flossie?” Papa pops his head round the door into my mother’s bedroom. “I’m just taking Lennie into town to buy some mince for the Blue Tit.”

“Please call her Gwendolen, her proper name. And shouldn’t you be working?” My mother’s voice sounds lighter than it has done these past few days. Perhaps she doesn’t have a headache any more.

Papa turns a deaf ear to her objections.

“Come here, Gwendolen.” Reluctantly, I enter the dark room. It smells of sleep and of something else too. Something old. My mother adjusts my dress and presses me against her. She is the source of the smell. When she releases me, I quickly run back to my father, who is waiting outside.

I skip along the broad pavement, in exact time with Papa’s footsteps. “Where are we going?”

“First to the butcher’s, and then to Mr Volt’s.”

I prance along, raising my legs higher and higher. I’m very good at it. My feet touch the ground at precisely the same point as Papa’s. Pa-dum, pa-dum. The hooves of a half-horse.

When we reach the butcher’s, Peter has to wait outside. He sits down immediately. He knows what he has to do. I stroke his white bib a moment, then quickly follow Papa into the shop.

“Some finely minced beef, please. It’s for a Blue Tit, so don’t give me too much.” Fat Jimmy doesn’t always serve in the shop, only if Mr Johnson, the butcher, isn’t there. He’s very slow and he doesn’t give me a slice of ham.

“Thank you. And may I also have a slice of ham, please?”

Fat Jimmy shrugs his shoulders and turns to slice the ham. My father gives me a wink. When we’re outside again, he tears the slice of ham in two. One half for Peter and one for me.

Mr Volt sells everything. One of his eyes droops a little lower than the other, and it bulges too. Duddie says someone once gave him a great thump and his eye flew out of his head and then it didn’t want to go back in again, and Olive says he can’t see out of it any more, but he always looks at me with it, as if he really can see me like that, as if he actually can see more with that eye than other people, things they can’t see.

“Good day, Mr Howard. Good day, young lady. What can I do for you both?”

“Some birdseed, please. For a little Blue Tit.”

“Certainly, sir. Our Universal Blend. How much would you like?” He takes down a canister from the topmost shelf, and picks up a paper bag.

“Just enough till the little one can fly again,” Papa says.

The whole shop is full of canisters and storage bins and in the corner there’s a skeleton. I walk towards it, finger the bones, and then shrink back when the skeleton starts moving.

“Oh, dearie me,” says Mr Volt. “Be careful now. Sometimes the spirit suddenly moves him.”

“How much do I owe you?” Papa asks.

“Oh, it’s hardly worth adding to your account, sir. Now then, young lady.”

I go to the counter.

“A bull’s eye or a humbug?”

“A humming bug, please!”

From one of the glass jars that are kept behind the counter, he takes out a sweetie. It’s green and red and looks like a stripy beetle.

“Thank you!” I curtsey to him, just like I’ve practised with Olive.

“What lovely manners!”

Peter races home ahead of us. The humbug melts in my mouth and it’s very sweet. I take it out to see if it still looks like a beetle. But the bug has become a flat patch. Paddy the Patch Bug.

Tessa opens the door for us, at the precise moment that we arrive. I run past her through the high-ceilinged entrance hall and into the parlour, where the box with the Blue Tit is still on the table.

“He’s still alive!”

“That’s good. So now we can get to work. What’s the time?”

I go and take a look at the clock on the windowsill. “It’s three o’clock.”

“Exactly three o’clock?”

“Almost exactly. One minute past, no, two minutes past three.”

“Yes, that’s almost exactly. Now listen. We must feed the birdie once an hour.” He forms some of the minced meat into a tiny ball and pushes it into the bird’s throat with his little finger. The bird swallows, and I give a very soft cheer.

“Soon I’ll mix the birdseed and the minced meat together, with a little water. And then it’s just a question of feeding him. If the birdie lives till tomorrow, you can feed him too.” He gives the Blue Tit another little ball of food, and then another, till the birdie doesn’t want any more. My father’s fingers are long and clever. I watch everything he does very closely, so that tomorrow I can do it too.

“Go and ask Cook if she has a foot stove. I have the impression that this little chap is cold.”

“Can’t I hold him?”

My father shakes his head. I run to the kitchen.

“Cook, Cook, we’ve got a little Blue Tit! And he’s cold! Do you perhaps have a foot stove for him?”

I hop from my left foot to my right foot, from my right foot to my left.

“Goodness gracious, child, calm down!”

Cook slowly gets out of her chair and stands up, groaning.

“Come on then, but no more shouting. Your mother isn’t well.”

I follow her down the steep, narrow staircase into the cellar. Small footsteps, my hand against the clammy wall.

“If he’s still alive tomorrow, then I’m allowed to feed him.”

Cook hums a little, then finds a foot stove in the open cupboard by the back wall. I take it from her.

“Tread carefully,” she calls after me, but I’m nearly upstairs already.

STAR 2

Countless numbers of Tits, Blackbirds, Sparrows and Robins lived in and around the garden of Bird Cottage. And there were also regular visitors, such as Jackdaws, Crows, Jays, Blue Tits, Finches and Woodpeckers. Some birds, such as the Swallows, returned every year; others visited now and then. There were birds who should have been summer visitors, but who stayed in the neighbourhood for their whole lives; others came for a season, or a number of years. Nearly every kind of bird has taken a peek inside the cottage at some point, but I have always tried to keep birds of the Crow family outside, as much as possible. They upset the smaller birds and rob their nests. The birds with whom I have developed the closest bond are the Great Tits. Great Tits are perhaps the cleverest birds of all, and full of curiosity. They are ideal research partners.

During their first visits Billy and Greenie were clearly quite nervous still, but very soon they began to stay inside, especially when the autumn gave way to a winter with several weeks of snow. Other Great Tits soon followed their example, and that December the first ones began to search for roosts in the house. Their choices were not always happy—they would roost between the curtain rods and the ceiling, or in the frame of a sliding door, which meant that it could no longer be closed—and so I began to hang boxes on the walls, or old food cartons, or small wooden cases. Each time they swiftly understood their purpose and it was not long before several diff erent Great Tits had taken possession of a roosting box of their own. They squabbled less about their roosts when they were inside than they did out of doors, perhaps because they viewed the cottage as my territory. In the breeding season, however, they always looked for anoutdoor spot where they could nest. Up to now, not one Tit has nested inside the house. Perhaps, after all, there is insufficient privacy here.

The Great Tits soon grew to know me, and although my presence sometimes influenced their behaviour (they would startle, for example, if I suddenly stood up; and when I was coming in I had to sing out “Peanut!” from behind the door, to tell them I was entering), most of the time they carried on as usual. Not only did that give me the opportunity to study their behaviour, I was also able to record their interrelationships from close at hand. In this way I became acquainted with around forty different Great Tits, all of whom had their own particular inclinations and wishes.

I learned from the birds themselves that individual intelligence plays a much greater role in their behaviour and choices than biologically determined tendencies, or “instinct”, as scientists call it. In order to study the birds like this, it was important to keep other human beings away from the cottage as much as possible. Birds react to the tiniest change in vocal inflection and to the smallest disturbance in their environment. Even visitors who did their best to make no noise often behaved in such a way that the birds would simply wish to escape as swiftly as possible. Once birds have had a shock it takes a long time for them to return—at least half a day, for the most part.

In my interactions with the Great Tits I have often felt myself to be slow and clumsy. Great Tits have better hearing than humans and a wider field of vision. Their eyes are on the sides of their heads and their vision is partly monocular (seeing differently with each eye) and partly binocular (with two eyes at the same time). This gives them a very wide range indeed. Their powers of observation are far sharper than those of humans. They are much more sensitive, not only to disturbances in their environment, but also to changes in the weather, to the colour of fruit and especially of berries, and to the movements of other creatures. There are,of course, many similarities too. Just like people, they are creatures of habit. Like us they have fixed rituals, when eating or going to sleep, for example. There are always around six or seven Great Tits sleeping in roosting boxes inside the house. Some birds only come indoors when it is really cold, but others will sleep in a box fixed to the picture rail below the bedroom ceiling for most of the year.

Like us, birds have countless ways of communicating with each other: through calls and songs, posture, the sound their wings make, eye contact, touching, movements, little dances. My interactions with the Great Tits soon became just as rich and varied. I regularly spoke to them. They would intuitively know from the tone of my voice what I intended, and in the course of time they learned the meaning of the words I used. They understood my gestures and we would make eye contact with each other. Some of the birds even enjoyed perching near me or on me.

Birds always see me quicker than I see them. When I turn my face towards them, they have already turned to me. And it is not only that they see me quicker because their eyes are set on the sides of their heads; it is also because they move more swiftly. At first I had the feeling that they understood me better than I understood them, but later I could read them just as well as they could read me. I understood some individuals better than others, of course, just as is the case with people. A few birds were really special: Baldhead, for example, the male Great Tit, who in the last days of his life was so tame that he lay in my lap all day long. And there was Twist, a brave and very intelligent female, who was my first guide in the language of Great Tits. And Star, of course, the cleverest Great Tit I have been privileged to know, and the one with whom I developed the closest ties.

1911

It feels as if someone has opened a door into my heart so the warmth can stream in. A little door, or a window perhaps. I run towards Olive, at the bottom of the garden, through the summer grass, the soft grass. Everything is so green.

“Is Father there yet?” she asks.

I shake my head. “Have you smelled the roses? Look, they’re in full bloom now.” I clasp hold of a rose in the hedge behind her and bend it down to her.

She nods, then stretches her back. “Would you be a darling and fetch me a drink? I’ve been on my feet all day.” She had to spend the day with Mother, shopping for dresses.

I walk back to the house, more slowly now, step by step by step. Mother stops me in the conservatory. “Gwen, are you ready for the performance? Your father will be down in less than half an hour. He’ll recite some of his latest poems, then Paul will read one of his sequences, and then you perhaps could play that Bach suite for us.”

I shrug my shoulders.

“Gwendolen.” She gives me a stern look.

“Yes, Mother.” I carry on to the kitchen, where I ask Tessa if I may have a glass of champagne, “For my sister.”

“And how are the birdies, miss?”

“The baby Great Tit didn’t survive. But yesterday I let the Magpie fly away. That seems to be going well.”

“You’re a real angel, miss. I was just saying that to Cook.”

I wave goodbye and take the champagne out. Paul is leaning against the doorpost, his curls making little circles on the wall, his face turned to the low evening sun. As I pass him, he turns towards me. I jump, blush, pretend I haven’t seen him.

“Gwendolen?”

I look back.

“Is that really wise, before your performance?”

“It’s for Olive.” My fingers firmly clasp the glass. I mustn’t grasp it too tightly, otherwise it will shatter. And I mustn’t let go.

“I know. I was just teasing.”

I blush even more now.

“I’m looking forward to hearing you play.”

I nod and swiftly walk on. The champagne is splashing over the brim of the glass and onto my fingers. I should have said something about his poems, that my father let me read them, and that they’re alive, they fly, they move me.

“Thanks.” Olive has put the parasol up, even though she is sitting in the shade. “Are you about to start?”

“Papa will be there soon. In half an hour.”

From the corner of my eye I can see Paul diminishing, a doll in evening dress, a little man on a bridal cake. My cousin Margie speaks of marriage as if it were a form of imprisonment.

“Will you play the Bach Cello Suite?”

I nod in agreement, running through the notes in my head.

“Is Stockdale here?”

“He’s supposed to be coming.” I hope he does. Stockdale conducts a London orchestra and it’s a while since he last heard me play. I’ve improved. I’ve studied very hard these past few months.

Charles, the Crow that Papa raised, flies into the ivy. He hops onto my outstretched hand, then back onto a branch. He doesn’t like all this commotion. He flies off and as he does so poops on the rim of Mr Wayne’s glass, who only spots it as he takes a sip of his champagne. Wayne teaches music in Towyn.

“That vile man.” Olive pulls a face.

Last time Stockdale was here he made eyes at Margie, rather conspicuously, I thought. She’s twenty-two years old and is studying at the Slade School of Art. She’s staying with us this summer because her parents are travelling. Margie flirts with everyone and they all put up with it because she seems so innocent. Stockdale clearly thought he’d hooked her, until at the end of the evening Margie began to yawn terribly and excused herself, giving a little wave at us from the staircase before vanishing.

Olive takes the bowl of nuts from the table and puts it on the edge of her chair. She picks out the tastiest, popping them into her mouth, one after another.

Tessa comes to fetch us. It’s warm inside, a throng of people, bodies that leave hardly any space, words that barely or don’t reach their targets. Words that simply express habit, that hardly mean anything else at all.

People travel far for these soirées. My father is the only one in this part of Wales to organise such evenings on a regular basis. Stockdale presses my hand. A little too long. He breathes out so heavily that the carnation in his buttonhole trembles.

My mother is standing by the grand piano. “I’d like to welcome all of you.” She speaks differently on these evenings, more affectedly.

I can see the broad, blond head of my brother Dudley on the other side of the room, and I move towards him, as inconspicuously as possible.

“I can wait.” My mother lifts an eyebrow. People are laughing. Dudley shifts along to make room for me.

Paul is sitting almost behind me. I become aware of how my back looks in this rose-coloured gown, chosen for me by Mother: too womanly, too close-fitting. My mother announces his name first and then mine, as if we belong together, as if our names follow each other’s by force of logic.

Newman, my father, starts with the second poem from his book Footsteps of Proserpine. It’s all about love and Blackbirds. Many of the poems in this collection were written for Mother. I suppress a yawn and move my fingers a little to warm them up. Ta-dada-da-dadada. He recites two more poems from his first collection, then declaims a long one about a city, which time has so much altered, and then another about the Trojan War, from his Greek cycle. His poems, without exception, are far too long and contain too many adjectives. Before Papa became a poet he was an accountant.

Kingsley, my oldest brother, rushes in panting and drops down so hard onto a chair in the back row that everyone turns around. He is still wearing flannels and I can smell him even from where I am seated. When I look at him, he pulls a funny face.

My father’s voice goes up a tone. He lets one more pause fall, then ends on a note of triumph. Paul walks to the front during the applause and I look at his feet, then briefly at his face, with the sun in it. My eyes fleetingly meet his. He is already speaking. I hardly hear what he says, but I know the words. And then it’s over.

My mother introduces me. I tune up. My fingers are tingling. And then I play: a question, an answer, a question.

* * *

When everyone has left, I come downstairs again. I go to where he stood, six feet away from where I was sitting, perhaps eight feet or so. I can see myself perched there, glancing sideways, turning my head. My cheeks are on fire again. Through the window I see my father pouring champagne into a glass. He gives it to my mother. The house is clearly breathing once again, through the open windows, while the last light of day dies away.

When I’d finished playing, Paul came to talk to me. He asked if I intended to take my musical ambitions further. I shrugged. “Possibly.”

“Then you must move to London.”

“I realise that.”

“I have acquaintances there. I could help you find lodgings.”

I nodded, thanked him, then said: “Sorry, but my mother wants to talk to me.” My mother! I’m almost eighteen.

“Of course.” He gave a nod and walked away. I took a deep breath, breathed in, breathed out. Outside the air smelled of grass and fire, of perfume. I thought he’d follow me, otherwise I’d still be speaking to him now. Expectations adhere to each other, forming even greater expectations. Something insignificant is added to the heap, and then something else, until it’s hard to see over the top, and then it’s difficult not to perceive yourself as hemmed in, and then it’s difficult to tell the difference between what is and what might be. Until he has gone, that is. Perhaps it will be weeks until I see him again. I should have said something smart or witty. The sun inside my breast departs, leaving a question mark in its place, an imprint of yearning. I could simply have talked to him a while. He wouldn’t have said what he did without a reason, those things about lodgings and acquaintances and so on. And he recited his poem about the woman who is always searching.

My father beckons me. I go outside.

“You played beautifully, my darling.” He hiccups, puts his arm around me, draws me towards him. The wind brings the smell of the sea with it, not the salt.

My mother drains her glass in one swift draught.

I wriggle free. “I want to study at the College of Music.”

“Sweetheart, you’re much too young still.” My father smiles apologetically at me.

“And then you’d have to move to London,” my mother says. “My little girl. I’m not sure you could cope.” She touches my cheek, gives it a little pinch.

“Of course I’ll cope.”

She is silent. My father stares into the dark garden.

“Of course I’ll cope,” I repeat, more loudly. “I’m not a child any more.”

My father puts his hand on my shoulder. I shake it off. Inside the house my shoes leave earth behind them, and grass. I meet my sister on the staircase, holding a plate with a sandwich in her hand. “Weren’t they charming?” she says. “Paul’s poems, I mean.”

“I think I love him,” I say.

“You’re in love, and that’s a completely different matter.” She looks at me sternly. “You mustn’t confuse one feeling with another, you know.” According to her it would be better not to act on feelings at all.

I heave a deep sigh.

“Stop acting all romantic.” She follows me into my room, sits on the bed and starts eating. She hardly eats at all during dinner and then afterwards she’s always hungry. “You really did play beautifully though.”