2,77 €

Mehr erfahren.

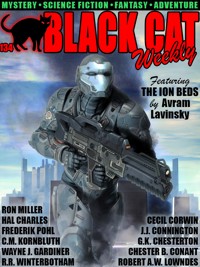

- Herausgeber: Black Cat Weekly

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This issue, we have 3 original tales. All are mysteries. Plus, we have 1 original science fiction tale, also a mystery. I leave you to unravel this puzzle! (Okay, I guess it’s not that much of a puzzle—one of the mysteries is also a science fiction story.) I moved Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken’s selection to the science fiction section (it was definitely science fiction) and I moved famous science fiction artist Ron Miller’s mystery into the lead spot. Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman’s story, by Wayne J. Gardner, is in the usual “Barb Goffman Presents” place.

For mysteries, we also have a G.K. Chesterton classic and a Golden Age novel by J.J. Connington. Plus, of course, a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles.

On the science fiction side, we have the “Michael Bracken Presents” story, Avram Lavinsky’s excellent “The Ion Bids Mystery,” plus tales by Cecil Corwin, R.R. Winterbotham, Chester B. Conant, plus a 3-way collaboration by C.M. Kornbluth, Robert A.W. Lowndes, and Frederik Pohl. Fun stuff!

Here’s the complete lineup—

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Velda Does a Good Deed,” by Ron Miller [short story]

“Who Grabbed the Golden Hammer of Thor?” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“I Remember It Well,” by Wayne J. Gardiner [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“The Asylum of Adventure,” by G.K. Chesterton [short story]

Mystery at Lynden Sands, by J.J. Connington [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Ion Beds Mystery”by Avram Lavinsky [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“Crisis!,” by Cecil Corwin [short story]

“The Thought-Feeders,” by R.R. Winterbotham [short story]

“Forbidden Flight,” by Chester B. Conant [short story]

“Einstein’s Planetoid,” by C.M. Kornbluth, Robert A.W. Lowndes, and Frederik Pohl [Novelet]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 672

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

VELDA DOES A GOOD DEED, by Ron Miller

WHO GRABBED THE GOLDEN HAMMER OF THOR?, by Hal Charles

THE ASYLUM OF ADVENTURE, by G.K. Chesterton

I REMEMBER IT WELL, by Wayne J. Gardiner

I REMEMBER IT WELL, by Wayne J. Gardiner

MYSTERY AT LYNDEN SANDS, by J.J. Connington

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter XIII. Cressida’s Narrative

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

THE ION BEDS MYSTERY, by Avram Lavinsky

CRISIS!, by Cecil Corwin

THE THOUGHT-FEEDERS by R.R. Winterbotham

FORBIDDEN FLIGHT by Chester B. Conant

EINSTEIN’S PLANETOID by C.M. Kornbluth, Robert A.W. Lowndes, and Frederik Pohl

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2024 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

Cover art by Luca Oleastri.

“Velda Does a Good Deed,” is copyright © 2024 by Ron Miller and appears here for the first time.

“Who Grabbed the Golden Hammer of Thor?” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“I Remember It Well” is copyright © 2024 by Wayne J. Gardiner and appears here for the first time.

“The Asylum of Adventure,” by G.K. Chesterton, was originally published in Maclean’s Magazine, Nov. 1, 1924.

Mystery at Lynden Sands, by J.J. Connington was originally published in 1928.

“The Ion Beds Mystery” is copyright © 2024 by Avram Lavinsky and appears here for the first time.

“Crisis!” by Cecil Corwin, was originally published in Science Fiction Quarterly, Spring 1942.

“The Thought-Feeders,” by R.R. Winterbotham, was originally published in Science Fiction, October 1941.

“Forbidden Flight,” by Chester B. Conant, was originally published in Future, October 1941.

“Einstein’s Planetoid,” by C.M. Kornbluth, Robert A.W. Lowndes, and Frederik Pohl was originally published in Science Fiction Quarterly, Spring 1942.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly.

This issue, we have 3 original tales. All are mysteries. Plus, we have 1 original science fiction tale, also a mystery. I leave you to unravel this puzzle! (Okay, I guess it’s not that much of a puzzle—one of the mysteries is also a science fiction story.) I moved Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken’s selection to the science fiction section (it was definitely science fiction) and I moved famous science fiction artist Ron Miller’s mystery into the lead spot. Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman’s story, by Wayne J. Gardner, is in the usual “Barb Goffman Presents” place.

For mysteries, we also have a G.K. Chesterton classic and a Golden Age novel by J.J. Connington. Plus, of course, a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles.

On the science fiction side, we have the “Michael Bracken Presents” story, Avram Lavinsky’s excellent “The Ion Bids Mystery,” plus tales by Cecil Corwin, R.R. Winterbotham, Chester B. Conant, plus a 3-way collaboration by C.M. Kornbluth, Robert A.W. Lowndes, and Frederik Pohl. Fun stuff!

Here’s the complete lineup—

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Velda Does a Good Deed,” by Ron Miller [short story]

“Who Grabbed the Golden Hammer of Thor?” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“I Remember It Well,” by Wayne J. Gardiner [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“The Asylum of Adventure,” by G.K. Chesterton [short story]

Mystery at Lynden Sands, by J.J. Connington [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Ion Beds Mystery”by Avram Lavinsky [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“Crisis!,” by Cecil Corwin [short story]

“The Thought-Feeders,” by R.R. Winterbotham [short story]

“Forbidden Flight,” by Chester B. Conant [short story]

“Einstein’s Planetoid,” by C.M. Kornbluth, Robert A.W. Lowndes, and Frederik Pohl [Novelet]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Paul Di Filippo

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Enid North

Karl Wurf

VELDA DOES A GOOD DEED,by Ron Miller

I’ve got to get out of this business. It’s not that I don’t like it, which I sometimes do, it’s just that I can’t seem to make any money. If it weren’t for Joe letting me eat on the house and the Loewensteins being nice enough to let my rent ride for the last three months, I don’t know what I’d be doing. Probably shedding feathers back on the runway at Slotnik’s, God forbid. I really don’t want to give up detecting, though—the Hawkshaw course cost me twenty bucks and I’d hate like anything to waste it. That twenty bucks wasn’t easy to come by.

Besides, I wasn’t quite ready yet to get the old hoo-ha from my erstwhile pals at the Follies. So I wasn’t too proud to say, sure, you bet, when Mr. Arkady offered me a sawbuck to run some errands for him. He’s the old coot that deals in antiquarian books who lives in the apartment directly across the hall from me on the third floor. I’d hardly ever seen him—which was OK by me since he’s looks like a vampire on a crash diet—let alone spoken to him, so I was surprised when he asked me to give him a hand. I said “sure” partly because I need the cash and partly from guilt. When Volume Seven of my course arrived—“Picking Locks and Performing Searches”—I’d used Arkady’s apartment to practice on. I was very pleased because he never knew I’d been there. Or at least I hoped not.

I’d found a note in my mailbox when I got back from the beach after caging lunch from my reporter pal, Chip. I still had my camera and the bag with my swimsuit with me, but figured I might as well find out what the old man wanted.

There was only a kind of distant croak in response to my knock, so, taking this as an invitation, I opened the door and went in. As I’d half expected, the place didn’t look any different than when I’d last seen it. It was dark—Arkady always kept the shades pulled—and smelled of mildew and decaying leather. A dump with about four million old books piled everywhere.

“Mr. Arkady?”

In response to my question there was a kind of honk from the direction of the bedroom (all of the apartments in the Zenobia Arms are laid out alike), that might have been, “In here, Miss Bellinghausen” and might have been, well, just a honk.

Winding my way through a narrow path between piles of moldy books, I found the bedroom. Arkady was sprawled on an old Army cot, looking even more like Dracula than ever.

“Ah, Miss Bellinghausen,” he said, settling the honk versus voice question, “thank you for coming.”

I said that he looked like Dracula, but even John Carradine would have looked healthy if placed next to Arkady. The old man really looked sick—kind of like the pictures I’ve seen of people in the German concentration camps, all shrunken and wasted away.

“You want me to get you a doctor, Mr. Arkady?” I asked as I put my bag and camera by the bed. “You look pretty rotten.”

“No, no—I do not trust doctors and, besides, they charge much too much money.”

“What can I do for you, then?”

“Well, first I must apologize for intruding on your time, Miss Bellinghausen—”

“Please call me Velda.”

“Velda, then. I must apologize, but I know you are the only one other than myself who is usually in the building for the greater part of the day.”

“God knows that’s true enough.”

As we spoke, I was taking a closer look around the place. Other than the bed with Arkady there was nothing but books, thousands and thousands of books.

“There must be a million books here!” I said.

“Some of them are very rare. This volume, for instance,” he said, holding up a flat, brown, beat-up looking old book, “is a copy of Tamarlane by Poe. It’s easily worth a hundred thousand dollars.”

“Holy cow!” I said, taking the book from him and turning it around in my hands. I’d seen better-looking phone books at the booth outside Joe’s. “If a book is worth that much, I bet some people would kill to get their hands on it.”

Little did I know that truer words have seldom been spoken.

“I was hoping,” Arkady said, “that, if it is not too much of an imposition, I might ask you to run a few errands for me…just until I get over this poor spell. For some reason I have been feeling extremely weak lately. I am afraid that I have many clients who are expecting my services and I cannot ignore them in the meantime.”

“I’d be glad to whatever I can, Mr. Arkady,” I said, glad for the offer of at least a diversion from my funk.

“I would be most happy to compensate you for your services—in fact, I would insist on it. Twenty dollars, perhaps?”

God, I wanted to do the right thing and say, “No, no, not at all! I’d be glad to lend you a hand. After all, what are good neighbors for?” But, Jesus! A sawbuck! So I swallowed hard and said that sounded just fine, thanks very much.

Well, it turned out to be the easiest twenty bucks I ever made. All I had to do was deliver bundles of old books to other old coots around town and collect Arkady’s fees. Most of these antique collectors—and you know how I meant that—were more than a little surprised to find me instead of Arkady when they answered their door, not that anyone seemed particularly disappointed. In fact, once they discovered that I wasn’t selling cosmetics or something, they seemed perfectly happy that Arkady hadn’t shown up. No one even asked about him.

More than once it was pretty hard tearing myself away from these old book collectors. I’d discovered that if I timed my deliveries just right I could usually promote a free lunch, since most of these geezers would have given me their last bowl of milk toast rather than see me leave. On the other hand, I’ve always hated places like hospitals and old folks’ homes and there was too much about the collectors’ homes that reminded me of them. Besides, while I don’t mind being ogled by rheumy-eyed octogenarians, neither do I want to be the cause of an embolism.

This went on for the rest of the week. By Sunday, it was pretty clear that Arkady wasn’t getting any better. So, again, I urged him to see a doctor and, like before, the stingy old bastard refused. That was a shame, but if he put that cheap a price on his own life, that was his own lookout.

Still, a couple of days later he was looking so godawful I thought that maybe I should try to figure out a way to get someone to see him. I mean, it was the least I could do. Besides, if he croaked that’d be the end of my weekly sawbuck. My first choice, naturally enough, was Doc Finlayson. He owed me for a big favor—the preservation of his license, no less—so he was always willing to make an installment on its repayment. As far as I was concerned, he’d repaid it several times over already, but who am I do say anything? So when I went down to Joe’s diner to bum another lunch, I used his phone to call the doctor. When he answered, I told him how awful Arkady looked and he sounded concerned and said he’d stop around that afternoon. I thanked him, hung up and went to the counter where Joe had a cheeseburger waiting for me.

“A client?” he asked, hopefully.

“I only wish. I’ve been picking up some spare change running errands for one of my neighbors who’s been sick. He seems to be getting a lot worse, so I asked Doc Finlayson to look in on him.”

“What do you think’s wrong with him?”

“Beats me. The guy’s about a thousand years old, so who knows?”

“Old guy, huh? Not the one who sells the antique books?”

“One and the same. Why? You know him?”

“Not exactly. Sold him my dad’s World War One diary last year. Gave me three hundred bucks for it.”

“No kidding? Kind of tough, though, wasn’t it? Selling something that personal and all?”

“Are you kidding? I never liked the bastard. Figured he owed me the three cees.”

* * * *

I’d only been back at my place for fifteen minutes when I heard the tentative tap at my door I recognized as Finlayson’s. I shouted for him to come in while I was changing clothes in the bedroom.

“Haven’t heard from you since that dreadful case with the Fort girl. How’ve you been?”

“So-so,” I replied, tucking my shirttail into my jeans as I came into the front room. “You know how it is.”

“All too well.”

“If you’re ready, I’ll take you over to Mr. Arkady’s room.”

“I’m glad you called me,” he said as I led the way into the hall, “but I’m surprised you did, since you have a doctor living right here.”

“What do you mean?”

“I saw his card on the mailbox downstairs as I came in. Doctor Rubrogra.”

“First I’ve heard of him. I knew someone new moved in a couple of days ago, but I’ve been so distracted running around for Arkady, I completely forgot about it. Funny place for a doctor to live, I’d think.”

“Well, you never can know about things…” Finlayson said uncomfortably, as he ran his finger around the inside of his collar. I knew what he meant. “Maybe he’s not a medical doctor. Maybe just a professor or some such thing.”

I didn’t bother to knock on Arkady’s door since his voice had gotten so weak I knew I wouldn’t be able to hear him whether he said “come in” or “get lost.” I told the doctor to wait while I went to the bedroom to tell the old man I’d brought someone to see him.

I’d only seen the book dealer the day before, but already he looked ten times worse. His skin was the color of old lard and had shrunk so close to his bones that it looked like it had been applied to his skeleton with a brush. He turned his eyes toward me and I thought they looked like a pair of fish eggs. I swallowed hard and told him that I’d brought a friend of mine, a doctor, who wanted to take a look at him. As I saw his mouth start to quiver with protest, I hastened to say that this was being done as a favor to me and wasn’t going to cost him a penny, at which news he relaxed. It was all pretty ghastly so I made no objection when Finlayson, who’d come in behind me, shooed me out of the room.

“Oh wait!” Arkady said in a voice that sounded like crumpling cellophane. “Doctor, will you give Miss Bellinghausen this? She left it here the other day.”

Finlayson came back out of the room with a little box hanging from strap. It was the camera I’d thought I’d lost. I’d been looking everywhere for it, too.

I decided to wander on downstairs to see what I could find out about my new neighbor from his mailbox. The card said only “Dr. Damien Rubrogra,” in the neat sort of copperplate hand that hadn’t been seen since the Harding administration. It didn’t tell me any more than what I’d heard from Finlayson. Rubrogra had moved into the apartment directly below Arkady’s, which would be 2A. I trotted back up the stairs and knocked at the door, not really expecting to find anyone home in the middle of the afternoon. I was half disappointed (because I’d kind of looked forward to a little lock-picking practice) when I heard the chain on the other side of the door rattling.

The door swung open a few inches and at first I thought the doctor must be standing behind it—until I glanced down and saw the little man glaring back up at me, the bright lenses of his pince-nez glasses making him look like some sort of ambulatory night light.

“Well?” he said belligerently, apparently not the least intimidated by the fact that I towered over him by at least a foot. He was a chunky little lump of a man who looked exactly like someone six feet tall who had been squashed by pressing really hard on top of his head. Evil little eyes glared out at me through the horizontal folds of his face.

“Oh, well, ah, Doctor Rugobra… I, ah, I live upstairs. I know that you’re new to the building and just thought I’d, ah, sort of welcome you to the, uh, neighborhood, sort of.”

“Is that so?”

“Well, uh, yeah, I guess.”

His gaze ran up and down me and I could actually feel it, like mice with cold, wet feet. He licked his lips—or what at least I guessed were his lips. They could have been just two more wrinkles for all I knew. The effect was much like that thing you do with kids where you make a fist and stick the tip of your thumb through the middle two fingers. You know what I mean? It doesn’t look as funny when a face does it, though.

“Say, do all the broads in this dump look as good as you?”

“Well, no, not really,” I replied. Ipheginia Birdwhistle, the aspiring Broadway star who lived on the top floor, was pretty good-looking, but she was short and blonde, so I wasn’t really lying to him.

“Say, if you really wanna welcome me to the place, why don’t you come in and have a drink? That’d be real friendly-like, you know?”

I knew all right.

“That’d be swell, but I better take a rain check on that. I got a sick friend upstairs I better get back to.”

“Do that again,” he said.

“Do what?”

“Show your teeth like you just did.”

“You mean like this?” I asked, baring my teeth like a grizzly bear or at least how I thought a grizzly bear would go about doing it.

“Hmmm.” he hmmmed, gazing up at my face from a foot below.

“What do you mean, ‘hmmm’?”

“Those are pretty nice teeth you have there, though that lower right lateral incisor looks a little iffy to me.”

“Pardon?.”

“You will have to excuse me. I’m a retired dentist, from Chillicothe. It’s hard to break old habits.”

While he was talking I was looking over his head into the room beyond. There wasn’t much to the place other than what I’d seen from the door. The front room was pretty much empty, except for a pile of cardboard boxes stacked up against a wall. Even the walls were bare.

Rugobra must have noticed the expression on my face. “You will have to excuse me,” he said, rubbing the palms of his hands together with the sound of a wet sponge being wrung out. “I’ve only just moved in, as you probably know, and most of my furniture hasn’t yet arrived.”

“You interested in photography?” I asked.

“What makes you ask that?”

“I noticed the enlarger in the other room,” I replied, wondering why he was suddenly so edgy.

“Oh, that’s just a sort of souvenir, really.”

“I would think that a key fob be easier to haul around.”

“It’s really only a hobby I indulge in now and then.”

It was a pretty serious hobby, I thought. The thing stood as tall as I do, a big gadget that looked a little like one of the spotlights at the Follies. It sat in the middle of what appeared to be an otherwise empty room. A heavy cord connected it to a wall socket.

Starting to feel pretty much like I do when I visit the snake house at the zoo, I made an excuse and hurried out of the place.

When I got back upstairs, Finlayson was just packing up his little black bag. I could see that Arkady was asleep.

“How’s he doing, doc?”

“Nothing really serious. Mostly age, lack of exercise and slight malnutrition. What’s really wrong with him is anemia. Haven’t seen a case like his since I was in Japan after the war. Here,” he said, tearing a little square of paper from a pad, “take this down to the pharmacy at the end of the block and have them fill it for you. Follow the directions and make sure the old man takes it. It’ll do him good. And make sure he eats.”

“Sure thing. I got some film here I got to run down there anyway, to get processed.”

* * * *

I paid my daily visit to Arkady the next morning.

“I brought you some chicken soup from Joe’s,” I said.

“You are an angel of mercy!”

“How are you feeling?”

“Still not so hot. And look here,” he said, leaning forward in bed and pulling up the back of his pajama shirt. The skin wasn’t the usual fish belly color. It was bright red. “How in the world do you suppose I got a sunburn while lying in bed?”

“Beats me.”

“What do you have there?”

“I got some medicine Dr. Finlayson said I was to make sure you took every day.”

I handed him the bottle and told him to follow the directions. Meanwhile, I opened the other package I’d picked up.

“What do you have there?” he asked.

“Some snapshots my pal Chip took of me down at Coney Island the other day.” I flipped through the glossy rectangles. “Aww, rats!”

“What’s the matter?”

“Look here,” I said, tossing the photos into his lap. “Every single one of them is fogged!”

* * * *

I showed the snapshots to Chip later and, to my surprise, he was more puzzled than upset.

“Anything wrong with your camera?” he asked.

“Take a look for yourself,” I said, handing him my Brownie. “Looks to be all in one piece to me.”

“There’s something weird looking about these pictures. I might have thought you’d just messed up rewinding the film or that maybe the drug store made a mistake. But look here,” he said, handing me one of the photos, “see that pattern? There’s not just fogging…there’s some sort of shadowy image, like gears or something.”

He asked if I’d mind if he showed the photos to F-Stop Fitzgerald, the paper’s staff photographer and I said sure, go ahead.

He called me the next day.

“F-Stop wants to know if you’ve been hanging around any hospitals lately.”

“Hospitals? Why would I be hanging around a hospital? I feel fine.”

“He said that your film was spoiled by X-rays. That pattern I saw? Those were the parts of your camera showing up on the prints.”

X-rays?

When I saw Arkady later that day, I told him that I thought someone had been deliberately trying to make him sick.

“Why? Whatever for?”

“I know you have books here that are worth a lot of money. Has anyone been trying to get you to sell any special book, one that you won’t let go or someone might think you’re asking too much for?”

“I don’t know… Well, there is this crank from somewhere in the midwest who’s been trying to buy a book from me for years. He’s gotten to be a real nuisance, though I haven’t heard anything from him for a couple of months.”

“What book is that?”

Arkady stretched a long, thin arm to the bookcase beside his bed and pulled out a small, brown book.

“This is a volume of poetry by Edward de Vere. He was a minor Elizabethan poet and the book has no real value. It’s just that I promised it to my niece, who is very fond of de Vere’s work for some reason.”

I took the book from him and turned it around in my hands. It was bound in leather that was shedding in feathery flakes, like a molting bird. It left powdery brown stains on my fingers. I flipped though it and was surprised to see how white the paper was. I guess they used better material back in de Vere’s day than in the true detective magazines I like to read.

I handed the book back to Arkady and asked, “Do you happen to have a worthless old book that looks just like this one?”

“Too many,” he replied. “Whyever do you ask?”

I met Rugobra coming down the stairs as I was going up to my apartment a couple of days later. He still looked like some kid’s clay model of a gnome that the kid had gotten tired of and punched. He had lips that looked like slivers of raw liver and he licked them like he liked how they tasted.

“My goodness,” he said, “you certainly seem pleased with yourself, Miss Bellinghausen.”

“Oh, but I am! That nice Mr. Arkady gave me this swell book of poetry for my birthday. Some old writer named de Vere. Wasn’t that sweet?”

Rugobra turned even grayer and broke out in a sweat like a squeezed sponge. He stared at the little book I had in my hand—which I had been carrying around for two days, for Pete’s sake—in much the same way I used to see the front row at Slotnik’s Follies looking at me.

That evening I decided that a nice hot shower would be just the ticket. I was just climbing into the stall when I heard a floorboard creak outside the door.

“About time!” I thought.

I had just enough time to grab a shirt and pull it on when the door burst open, admitting an ugly little munchkin with an automatic in its pudgy paw.

“Eek!” I said in feigned surprise.

“Get your hands up, lady!” Rugobra said, trying his best to sound like Humphrey Bogart and failing.

“You’re in the wrong bathroom in the wrong apartment on the wrong floor,” I said.

“But I don’t have the wrong dame! Where’s that book?”

“What book?”

“Don’t play dumb with me. From the looks of you, it’s probably the only book you own.”

I resented that. I have at least five or six books.

“You know exactly which book I mean,” he continued. “That book Arkady gave you. It’s rightly mine.”

“So what’s so important about an old book?”

“Edward de Vere is the man that many experts, myself included, believe was the actual author of Shakespeare’s plays.”

“Do tell.”

“I am convinced there is a letter from de Vere hidden in the binding that proves this is true. The discovery will make me the greatest expert on Shakespeare in the world!”

“You’ll still look like a garden gnome,” I said. “But what about the X-rays? I figured that out. That’s no photographic enlarger you got, it’s an X-ray machine. And it’s right under Arkady’s bedroom.”

“I figured if I could bump off the old man without anyone getting wise, I could buy the book for a song at the estate sale.”

“Well, if you want it so bad, the book’s right here in the bathroom.”

“What?”

“See? Over there hanging above the sink.”

He looked where I was pointing. I probably could have kicked the gun out of his hand right then, but I was starting to have too much fun. What he saw was a little brown book dangling at the end of a string attached to the ceiling light fixture. It was wet and dripping an oily-looking liquid into the sink.

“What are you doing?”

“There it is. Soaked in bug killer.”

I took two steps over to the sink and picked up a Zippo cigarette lighter that was sitting by the tap. I snapped it open and an inch-long flame licked up.

“And what do you suppose might happen if I got a little careless with this thing?”

“You wouldn’t dare!”

“You think not?” I said, touching the flame to a corner of the book. There was a soft POOF as the book almost instantly disintegrated in a flash. A shower of greasy black ashes fell into the sink.

“NO!”

Rugobra dropped the gun and grabbed his throat with one hand and his chest with the other. I heard a muffled pop that was probably an artery or something exploding. He dropped like the sack of potatoes he resembled.

I knelt and felt for a pulse, being pretty sure I wouldn’t find one. I was right.

“Well,” I thought, “I guess that was a kind of poetry.”

A few hours later, after I’d called Lieutenant Dillinger and had the mess in my bathroom cleaned up, I went down to Arkady’s place to report what had happened. I hadn’t told Dillinger much, just that my new neighbor had broken into my apartment and dropped dead from a heart attack. Dillinger said that he wasn’t surprised, me being dressed as I had been, and let it go at that. I was a little more forthcoming with Arkady.

“Good heavens, Velda!” he said. “Weren’t you a little rough on the man?”

“No one fries one of my friends and gets away with it.”

So, if there is any real moral to this report, try to remember that no matter how badly you might want something it’s never right to try to get it by exposing an old man to dangerous radiation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ron Miller is an author/illustrator specializing in science, science fiction and fantasy. He is responsible for 73 books of his own, many of which have received awards and commendations, including a Hugo. He has designed postage stamps (one of which is attached to the New Horizons spacecraft) and has worked on motion pictures such as “Dune.”

WHO GRABBED THEGOLDEN HAMMER OF THOR?,by Hal Charles

Detective Kelly Stone had never been so excited about a case. Housemakers, the top-rated cable show about constructing new homes, was the favorite program of both her and her father, an ex-contractor. Watching a new house go up was almost as fun as the banter between the Flicker triplets, the show’s hosts, and this coming season’s added bonus—Housemakers was being filmed in her home town.

No sooner had she parked her car at the build site than she was greeted by a cute, small woman with a blonde ponytail. “Thank you for coming so quickly, Detective Stone. I’m Teresa Taylor, the showrunner for Housemakers.”

“My dispatcher must have received a garbled message,” admitted Kelly, “because she said something about the Golden Hammer of Thor being missing.”

Teresa Taylor laughed. “I suppose that description does sound a lot like typical TV hyperbole. At the end of the shooting season, which is next week, I was going to try something new—presenting the so-called hammer to the triplet who does the best job. But this morning the award was missing from my house.”

“Sounds interesting.”

“More like necessary. Harry, Gary, and Mary Flicker have evolved a poor working relationship. They spend most of their off-camera time sniping at each other.”

“That attitude sure doesn’t come across on the show,” said Kelly.

“Are you a real detective or just another actor Teresa hired?” said a female, who looked like she spent most of her time pumping iron.

“Mary Flicker, Detective Kelly Stone,” introduced the showrunner. “She’s here about the missing hammer.”

“I have never once visited that sawdust-covered rental where Teresa lives,” said Mary. “Besides, I spent last night at a local bar, The Nighthawk, out-drinking the locals. Unfortunately, there were a lot of losers with bruised male egos down there who might have trouble admitting they lost to a woman.”

“The Nighthawk recently installed a whole-establishment camera system for insurance purposes,” said Kelly, “so your story should be easy to check on.”

“Gotta go learn how to use the new mortiser,” said Mary, departing.

“Gee, Mary,” said a male voice, “then you’ll have one tool in your tool kit that you can actually use.”

“Detective Stone,” said Teresa, “meet Gary Flicker.”

Kelly shook hands with the triplet who looked much less addicted to iron than his sister.

“Before you even ask, Detective, I spent the entire night here trying to figure out how to lay flooring straight when the addition juts out at a five-degree angle.”

“I left last night about midnight,” confirmed the showrunner, “and Gary was here when I arrived at sun-up.”

“If you’ll excuse me,” said Gary. “The plumbing in the crawlspace doesn’t have the proper downward pitch, and I’ve got to fix it.”

As he walked off, Kelly said, “Gary seems quite dedicated to the integrity of the house-build. By the way, is the so-called Golden Hammer of Thor worth much?”

“It’s got more gold in it than the entire town has in their crowns,” said Teresa. “The web…network thought it was worth forking out the money to keep the peace on their highest-rated show.”

“It’s worth more than five times my contract,” said the suddenly-appearing Harry Flicker. “I think Mary took it because her bad attitude caused the web not to renew her contract next year.”

“The second part’s true,” admitted Teresa. “And Mary’s become an alcoholic, so she’s an insurance nightmare for the production company.”

“I see,” said Kelly. Then she turned to Harry. “Got an alibi for last night?”

Harry whispered in her ear. “I was with Teresa all night, but don’t let the cat out of the bag.”

“Don’t need to,” said the detective. “I think I know who stole the Golden Hammer of Thor.”

SOLUTION

Mary was a liar. Kelly suddenly realized that the female triplet had made a contradictory statement. How could she know that showrunner Teresa’s rental was sawdust-covered if she had, as she claimed, never been there? The Nighthawk’s cameras confirmed Kelly’s diagnosis. Mary is currently employing her miniscule woodworking talents in the carpenter shop of state’s lock-up. Teresa awarded the Golden Hammer of Thor to Gary, which caused Harry to break up with her. Teresa then, in true reality TV-fashion, exchanged her sawdust-covered rental for Gary’s spic-and-span, sixth-floor condo.

THE ASYLUM OF ADVENTURE,by G.K. Chesterton

A VERY small funeral procession passed through a very small churchyard on the rocky coast of Cornwall; carrying a coffin to its grave under the low and windy wall. The coffin was quite formal and unobtrusive; but the knot of fishermen and labourers eyed it with the slanted eyes of superstition; almost as if it had been the misshapen coffin of legend that was said to contain a monster. For it contained the body of a near neighbour, who had long lived a stone’s throw from them, and whom they had never seen.

The figure following the coffin, the chief and only mourner, they had seen fairly often. He had a habit of disappearing into his late friend’s house and being invisible for long periods, but he came and went openly. No one knew when the dead man had first come, but he probably came in the night; and he went out in the coffin. The figure following it was a tall figure in black, bareheaded, with the sea-blast whistling through his wisps of yellow hair as through the pale sea grasses. He was still young and none could have said that his mourning suit sat ill upon him; but some who knew him would have seen it with involuntary surprise, and felt that it showed him in a new phase. When he was dressed, as he generally was, in the negligent tweeds and stockings of the pedestrian landscape-painter, he looked merely amiable and absent-minded; but the black brought out something more angular and fixed about his face. With his black garb and yellow hair he might have been the traditional Hamlet; and indeed the look in his eyes was visionary and vague; but the traditional Hamlet would hardly have had so long and straight a chin as that which rested unconsciously on his black cravat. After the ceremony, he left the village church and walked towards the village post office, gradually lengthening and lightening his stride, like a man who, with all care for decency, can hardly conceal that he is rid of a duty.

“It’s a horrible thing to say,” he said to himself, “but I feel like a happy widower.”

He then went in to the post office and sent off a telegram addressed to a Lady Diana Westermaine, Westermaine Abbey: a telegram that said: “I am coming morrow to keep my promise and tell you the story of a strange friendship.”

Then he went out of the little shop again and walked eastwards out of the village, with undisguised briskness, till he had left the houses far behind, and his funeral hat and habit were an almost incongruous black spot upon great green uplands and the motley forests of autumn. He had walked for about half a day, lunched on bread and cheese and ale at a little public-house, and resumed his march with unabated cheerfulness, when the first event of that strange day befell him. He was threading his way by a river that ran in a hollow of the green hills; and at one point his path narrowed and ran under a high stone wall. The wall was built of very large flat stones of ragged outline, and a row of them ran along the top like the teeth of a giant. He would not normally have taken so much notice of the structure of the wall; indeed he did not take any notice of it at all until after something had happened. Until (in fact) there was a great gap in the row of craggy teeth, and one of the crags lay flat at his feet, shaking up dust like the smoke of an explosion. It had just brushed one of his long wisps of light hair as it fell.

Looking up, a shade bewildered by the shock of his hairbreadth escape, he saw for an instant in the dark gap left in the stonework a face, peering and malignant. He called out promptly:

“I see you; I could send you to jail for that!”

“No you can’t,” retorted the stranger, and vanished into the twilight of trees as swiftly as a squirrel.

The gentleman in black, whose name was Gabriel Gale, looked up thoughtfully at the wall, which was rather too high and smooth to scale; besides the fugitive had already far too much of a start. Mr. Gale finally said aloud, in a reflective fashion: “Now I wonder why he did that!” Then he frowned with an entirely new sort of gravity, and after a moment or two of grim silence he added: “But after all it’s much more odd and mysterious that he should say that.”

In truth, though the three words uttered by the unknown person seemed trivial enough, they sufficed to lead Gale’s memories backwards to the beginning of the whole business that ended in the little Cornish churchyard; and as he went briskly on his way he rehearsed all the details of that old story, which he was to tell to the lady at his journey’s end.

* * * *

Nearly fourteen years before, Gabriel Gale had come of age and inherited the moderate debts and the small freehold of a rather unsuccessful gentleman farmer. But though he grew up with the traditions of a sort of small squire, he was not the sort of person, especially at that age, to have no opinions except those traditions. In early youth his politics were the very reverse of squires’ politics; he was very much of a revolutionary and locally rather a firebrand. He intervened on behalf of poachers and gipsies: he wrote letters to the local papers which the editors thought too eloquent to be printed. He denounced the county magistracy in controversies that had to be impartially adjudged by the county magistrates. Finding, curiously enough, that all these authorities were against him, and seemed to be in legal control of all his methods of self-expression, he invented a method of his own which gave him great amusement and the authorities great annoyance. He fell, in fact, to employing a talent for drawing and painting which he was conscious of possessing, along with another talent for guessing people’s thoughts and getting a rapid grasp of their characters, which he was less conscious of possessing, but which he certainly possessed. It is a talent very valuable to a portrait-painter: in this case, however, he became a rather peculiar sort of portrait painter. It was not exactly what is generally called a fashionable portrait painter. Gale’s small estate contained several outhouses with whitewashed walls or palings abutting on the high road; and whenever a magnate or magistrate did anything that Gale disapproved of, Gale was in the habit of painting his portrait in public and on a large scale. His pictures were hardly in the ordinary sense caricatures, but they were the portraits of souls. There was nothing crude about the picture of the great merchant prince now honoured with a peerage; the eyes looking up from under lowered brows, the sleek hair parted low on the forehead, were hardly exaggerated; but the smiling lips were certainly saying: “And the next article?” One even knew that it was not really a very superior article. The picture of the formidable Colonel Ferrars did justice to the distinction of the face, with its frosty eyebrows and moustaches; but it also very distinctly discovered that it was the face of a fool, and of one subconsciously frightened of being found to be a fool.

With these coloured proclamations did Mr. Gale beautify the countryside and make himself beloved among his equals. They could not do very much in the matter; it was not libel, for nothing was said; it was not nuisance or damage, for it was done on his own property, though in sight of the whole world. Among those who gathered every day to watch the painter at work, was a sturdy, red-faced, bushy-whiskered farmer, named Banks, seemingly one of those people who delight in any event and are more or less impenetrable by any opinion. He never could be got to bother his head about the sociological symbolism of Gale’s caricatures; but he regarded the incident with exuberant interest as one of the great stories calculated to be the glory of the country, like a calf born with five legs or some pleasant ghost story about the old gallows on the moor. Though so little of a theorist he was far from being a fool, and had a whole tangle of tales both humorous and tragic, to show how rich a humanity was packed within the four corners of his countryside. Thus it happened that he and his revolutionary neighbour had many talks over the cakes and ale, and went on many expeditions together to fascinating graves or historic public houses. And thus it happened that on one of these expeditions Banks fell in with two of his other cronies, who made a party of four, making discoveries not altogether without interest.

The first of the farmer’s friends, introduced to Gale under the name of Starkey, was a lively little man with a short stubbly beard and sharp eyes, which he was in the habit however of screwing up with a quizzical smile during the greater part of a conversation. Both he and his friend Banks were eagerly interested in the story of Gale’s political protests, if they regarded them only too much as practical jokes. And they were both particularly anxious to introduce a friend of theirs named Wolfe, always referred to as Sim, who had a hobby, it would seem, in such matters, and might have suggestions to make. With a sort of sleepy curiosity which was typical of him, Gale found himself trailed along in an expedition for the discovery of Sim; and Sim was discovered at a little obscure hostelry called the Grapes a mile or so up the river. The three men had taken a boat, with the small Starkey for coxswain; it was a glorious autumn morning but the river was almost hidden under high banks and overhanging woods, intersected with great gaps of glowing sunlight, in one of which the lawns of the little riverside hotel sloped down to the river. And on the bank overhanging the river a man stood waiting for them; a remarkable looking man with a fine sallow face rather like an actor’s and very curly grizzled hair. He welcomed them with a pleasant smile, and then turned towards the house with something of a habit of command or at least of direction. “I’ve ordered something for you,” he said. “If we go in now it will be ready.”

As Gabriel Gale brought up the rear of the single file of four men going up the straight paved path to the inn door, his roaming eye took in the rest of the garden, and something stirred in his spirit, which was also prone to roaming, and even in a light sense to a sort of rebellion. The steep path was lined with little trees, looking like the plan of a sampler. He did not see why he should walk straight up so very straight a path, and many things in the garden took his wandering fancy. He would much rather have had lunch at one of the little weather-stained tables standing about on the lawn. He would have been delighted to grope in the dark and tumble-down arbour in the corner, of which he could dimly see the circular table and semi-circular seat in the shadow of its curtain of creepers. He was even more attracted by the accident by which an old children’s swing, with its posts and ropes and hanging seat, stood close up to the bushes of the river bank. In fact, the last infantile temptation was irresistible; and calling out, “I’m going over here,” he ran across the garden towards the arbour, taking the swing with a sort of leap on his way. He landed in the wooden seat and swung twice back and forth, leaving it again with another flying leap. Just as he did so, however, the rope broke at its upper attachment, and he fell all askew, kicking his legs in the air. He was on his feet again immediately, and found himself confronted by his three companions who had followed in doubt or remonstrance. But the smiling Starkey was foremost, and his screwed-up eyes expressed good humour and even sympathy.

“Rotten sort of swing of yours,” he said. “These things are all falling to pieces,” and he gave the other rope a twitch, bringing that down also. Then he added: “Want to feast in the arbour, do you? Very well; you go in first and break the cobwebs. When you’ve collected all the spiders, I’ll follow you.”

Gale dived laughing into the dark corner in question and sat down in the centre of the crescent-shaped seat. The practical Mr. Banks had apparently entirely refused to carouse in this leafy cavern; but the figures of the two other men soon darkened the entrance and they sat down, one at each horn of the crescent.

“I suppose that was a sudden impulse of yours,” said the man named Wolfe, smiling. “You poets often have sudden impulses, don’t you?”

“It’s not for me to say it was a poet’s impulse,” replied Gale; “but I’m sure it would need a poet to describe it. Perhaps I’m not one; anyhow I never could describe those impulses. The only way to do it would be to write a poem about the swing and a poem about the arbour, and put them both into a longer poem about the garden. And poems aren’t produced quite so quickly as all that, though I’ve always had a notion that a real poet would never talk prose. He would talk about the weather in rolling stanzas like the stormclouds, or ask you to pass the potatoes in an impromptu lyric as beautiful as the blue flower of the potato.”

“Make it a prose poem, then,” said the man whose name was Simeon Wolfe, “and tell us how you felt about the garden and the garden-swing.”

Gabriel Gale was both sociable and talkative; he talked a great deal about himself because he was not an egoist. He talked a great deal about himself on the present occasion. He was pleased to find these two intelligent men interested and attentive; and he tried to put into words the impalpable impulses to which he was always provoked by particular shapes or colours or corners of the straggling road of life. He tried to analyse the attraction of a swing, with its rudiments of aviation; and how it made a man feel more like a boy, because it made a boy feel more like a bird. He explained that the arbour was fascinating precisely because it was a den. He told them at some length of the psychological truth; that dismal and decayed objects raise a man’s spirits higher, if they really are already high. His two companions talked in turn; and as luncheon progressed and passed they turned over between them many strange strata of personal experience, and Gale began to understand their personalities and their point of view. Wolfe had travelled a great deal, especially in the East; Starkey’s experiences had been more local but equally curious, and they both had known many psychological cases and problems about which to compare notes. They both agreed that Gale’s mental processes in the matter, though unusual, were not unique.

“In fact,” observed Wolfe, “I think your mind belongs to a particular class, and one of which I have had some experience. Don’t you think so, Starkey?”

“I quite agree,” said the other man, nodding.

It was at that moment that Gale looked out dreamily at the light upon the lawn, and in the stillness of his inmost mind a light broke on him like lightning; one of the terrible intuitions of his life.

Against the silver light on the river the dark frame of the forsaken swing stood up like a gallows. There was no trace of the seat or the ropes, not merely in their proper place, but even on the ground where they had fallen. Sweeping his eye slowly and searchingly round the scene, he saw them at last, huddled and hidden in a heap behind the bench where Starkey was sitting. In an instant he understood everything. He knew the profession of the two men on each side of him. He knew why they were asking him to describe the processes of his mind. Soon they would be taking out a document and signing it. He would not leave that arbour a free man.

“So you are both doctors,” he observed cheerfully, “and you both think I am mad.”

“The word is really very unscientific,” said Simeon Wolfe in a soothing fashion. “You are of a certain type which friends and admirers will be wise to treat in a certain way, but it need in no sense be an unfriendly or uncomfortable way. You are an artist with that form of the artistic temperament which is necessarily a mode of modified megalomania, and which expresses itself in the form of exaggeration. You cannot see a large blank wall without having an uncontrollable appetite for covering it with large pictures. You cannot see a swing hung in the air without thinking of flying ships careering through the air. I will venture to guess that you never see a cat without thinking of a tiger or a lizard without thinking of a dragon.”

“That is perfectly correct,” said Gale gravely; “I never do.”

Then his mouth twisted a little, as if a whimsical idea had come into his mind. “Psychology is certainly very valuable,” he said. “It seems to teach us how to see into each other’s minds. You, for instance, have a mind which is very interesting: you have reached a condition which I think I recognize. You are in that particular attitude in which the subject, when he thinks of anything, never thinks of the centre of anything. You see only edges eaten away. Your malady is the opposite to mine, to what you call making a tiger out of a cat, or what some call making a mountain out of a molehill. You do not go on and make a cat more of a cat; you are always trying to work back and prove that it is less than a cat; that it is a defective cat or a mentally deficient cat. But a cat is a cat; that is the supreme sanity which is so thickly clouded in your mind. After all, a molehill is a hill and a mountain is a hill. But you have got into the state of the mad queen, who said she knew hills compared with which this was a valley. You can’t grasp the thing called a thing. Nothing for you has a central stalk of sanity. There is no core to your cosmos. Your trouble began with being an atheist.”

“I have not confessed to being an atheist,” said Wolfe staring.

“I have not confessed to being an artist,” replied Gale, “or to have uncontrolled artistic appetites or any of that stuff. But I will tell you one thing: I can only exaggerate things the way they are going. But I’m not often wrong about the way they are going. You may be as sleek as a cat but I knew you were evolving into a tiger. And I guessed this little lizard could be turned by black magic into a dragon.”

As he spoke he was looking grimly at Starkey and out under the dark arch of the arbour, as out of a closing prison, with these two ghouls sitting on each side of the gate. Beyond was the gaunt shape like a gallows and beyond that the green and silver of the garden and the stream shone like a lost paradise of liberty. But it was characteristic of him that even when he was practically hopeless, he liked being logically triumphant; he liked turning the tables on his critics even when, so to speak, they were as abstract as multiplication tables.

“Why, my learned friends,” he went on contemptuously, “do you really suppose you are any fitter to write a report on my mind than I am on yours? You can’t see any further into me than I can into you. Not half so far. Didn’t you know a portrait painter has to value people at sight as much as a doctor? And I do it better than you; I have a knack that way. That’s why I can paint those pictures on the wall; and I could paint your pictures as big as a house. I know what is at the back of your mind, Doctor Simeon Wolfe; and it’s a chaos of exceptions with no rule. You could find anything abnormal, because you have no normal. You could find anybody mad; and as for why you specially want to find me mad—why that is another disadvantage of being an atheist. You do not think anything will smite you for the vile treachery you have sold yourself to do day.”

“There is no doubt about your condition now,” said Dr. Wolfe with a sneer.

“You look like an actor, but you are not a very good actor,” answered Gale calmly. “I can see that my guess was correct. These rack-renters and usurers who oppress the poor, in my own native valley, could not find any pettifogging law to prevent me from painting the colours of their souls in hell. So they have bribed you and another cheap doctor to certify me for a madhouse. I know the sort of man you are. I know this is not the first dirty trick you have done to help the rich out of a hole. You would do anything for your paymasters. Possibly the murder of the unborn.”

Wolfe’s face was still wrinkled with its Semitic sneer, but his olive tint had turned to a sort of loathsome yellow. Starkey called out with sudden shrillness, as abrupt as the bark of a dog.

“Speak more respectfully!”

“There is Dr. Starkey, too,” continued the poet lazily. “Let us turn our medical attention to the mental state of Dr. Starkey.”

As he rolled his eyes with ostentatious languor in the new direction, he was arrested by a change in the scene without. A strange man was standing under the frame of the swing, looking up at it with his head on one side like a bird’s. He was a small, sturdy figure, quite conventionally clad; and Gale could only suppose he was a stray guest of the hotel. His presence did not help very much; for the law was probably on the side of the doctors; and Gale continued his address to them.

“The mental deficiency of Dr. Starkey,” he said, “consists in having forgotten the truth. You, Starkey, have no sceptical philosophy like your friend. You are a practical man, my dear Starkey; but you have told lies so incessantly and from so early an age that you never see anything as it is, but only as it could be made to look. Beside each thing stands the unreal thing that is its shadow; and you see the shadow first. You are very quick in seeing it; you go direct to the deceptive potentialities of anything; you see at once if anything could be used as anything else. You are the original man who went straight down the crooked lane. I could see how quickly you saw that the swing would provide ropes to tie me up if I were violent; and that going first into this arbour, I should be cornered, with you on each side of me. Yet the swing and the arbour were my own idea; and that again is typical of you. You’re not a scientific thinker like the other scoundrel; you have always picked up other men’s ideas, but you pick as swiftly as a pickpocket. In fact, when you see an idea sticking out of a pocket you can hardly help picking it. That’s where you’re mad; you can’t resist being clever, or rather borrowing cleverness. Which means you have sometimes been too clever to be lucky. You are a shabbier sort of scamp; and I rather fancy you have been in prison.”

Starkey sprang to his feet, snatching up the ropes and throwing them on the table.

“Tie him up and gag him,” he cried; “he is raving.”

“There again,” observed Gale, “I enter with sympathy into your thoughts. You mean that I must be gagged at once; for if I were free for half a day, or perhaps half an hour, I could find out the facts about you and tear your reputation to rags.”

As he spoke he again followed with an interested eye the movements of the strange man outside. The man had recrossed the garden, calmly picking up a chair from one of the little tables, and returned carrying it lightly in the direction of the arbour. To the surprise of all, he set it down at the round table in the very entrance of that retreat, and sat down on it with his hands in his pockets, staring at Gabriel Gale. With his face in shadow, his square head, short hair and bulk of shoulders took on a new touch of mystery.

“Hope I don’t interrupt,” he said. “Perhaps it would be more honest to say I hope I do interrupt. Because I want to interrupt. Honestly, I think you medical gentlemen would be very unwise to gag your friend here, or try to carry him off.”

“And why?” asked Starkey sharply.

“Only because I should kill you if you did,” replied the stranger.

They all stared at him; and Wolfe sneered again as he said: “You might find it awkward to kill us both at once.”

The stranger took his hands out of his pockets; and with the very gesture there was a double flash of metal. For the hands held two revolvers which pointed at them, fixed them like two large fingers of steel.

“I shall only kill you if you run or call out,” said the strange gentleman pleasantly.

“If you do you’ll be hanged,” cried Wolfe violently.