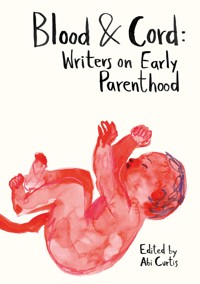

Blood & Cord E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Emma Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

A child is born and everything is made anew. In this blur of new beginnings there are tears and laughter, new words and new silences: this is an unmaking and remaking of the self. From short stories about unnerved fathers and lost mothers, to poems about 'half-built Lego palaces' and friends who share their deepest secrets, Blood & Cord is a raw exploration of new parenthood. Voicing silenced conversations about loss, grief, and loneliness, as well as the joys and laughter that are part and parcel of becoming a parent, the stories told within offer a refreshingly honest account of life after new life. This collection is a hand in the dark, offering comfort and solidarity to any new parent.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 90

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

"Many kinds of parenthood are presented in this superb new collection of poems and stories. Mothers and fathers convey the spectrum of ways in which the self is remade by parenthood, the 'complete subjugation' of this task – bodily, mentally, spiritually – tearing apart the boundaries of love for which new language is required. Thankfully, the writers herein are more than up to this otherwise monumental task. New and experienced parents alike will find solace and resonance in this wonderful book." – Carolyn Jess-Cooke

OTHER TITLES FROM THE EMMA PRESS

SHORTSTORIESANDESSAYS

How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart, by Florentyna Leow

Night-time Stories, edited by Yen-Yen Lu

Hailman, by Leanne Radojkovich

Postcard Stories 2, by Jan Carson

Tiny Moons: A year of eating in Shanghai, by Nina Mingya Powles

POETRYCOLLECTIONS

Europe, Love Me Back, by Rakhshan Rizwan

POETRYANDARTSQUARES

The Strange Egg, by Kirstie Millar, illustrated by Hannah Mumby

The Fox's Wedding, by Rebecca Hurst, illustrated by Reena Makwana

Pilgrim, by Lisabelle Tay, illustrated by Reena Makwana

One day at the Taiwan Land Bank Dinosaur Museum, by Elīna Eihmane

BOOKSFORCHILDREN

We Are A Circus, by Nasta, illustrated by Rosie Fencott

Cloud Soup, by Kate Wakeling, illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa

The Bee Is Not Afraid of Me: A Book of Insect Poems, edited by Fran Long and Isabel Galleymore

My Sneezes Are Perfect, by Rakhshan Rizwan, illustrated by Benjamin Phillips

POETRYPAMPHLETS

Milk Snake, by Toby Buckley

Ovarium, by Joanna Ingham

THEEMMAPRESS

First published in the UK in 2023 by The Emma Press Ltd.

Texts © individual writers 2023.

Selection and introduction © Abi Curtis 2023.

Cover design © Elīna Brasliņa 2023.

All rights reserved.

The rights of Abi Curtis to be identified as the editor of this anthology and of the writers to be identified as the authors of their texts have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 978-1-915628-15-2

EPUBISBN 978-1-915628-16-9

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books, Padstow.

The Emma Press

theemmapress.com

Birmingham, UK

INTRODUCTION FROM THE EDITOR

The birth of a baby is like a comet crashing into your living room, like a door inside yourself opening up, like being inside a tempest. Becoming a new parent is one of life’s greatest joys, and much of what we read and see on social media and in popular culture tells us so: blooming mothers flushed with love, adoring, doting fathers, proud grandparents. But there is an unedited side to the story: it is also full of other emotions, some of them ambivalent, and this storm of emotions is often under-portrayed. Becoming a parent can be a kind of un-making of the self. You lose your old life in many ways, both physically and emotionally. From the intensity of birth, to the strange hinterlands of sleepless nights, from the pain of baby loss, to the ferocity of love, to the sensation of having allowed a being into your world who will change it forever.

The remade version of the parent has undergone a profound transformation. The writers in this collection, some fathers, some mothers, explore this territory with searing honesty and originality. The introduction of a new baby rearranges a life, and this requires a new language and a new kind of engagement with the world. The fictions, memoirs and poetry within these pages will illuminate parenthood in unexpected ways. The title, Blood & Cord, is taken from a beautiful poem by Gail McConnell, ‘Talk Through the Wall’, which explores a form of parenthood where both parents are women, and the speaker of the poem seeks to situate herself as the partner who is not pregnant. This exemplifies how the anthology aims to represent many possible versions of parenthood. The writers here are already known and admired for their writing on parenthood, and with brand new work and work collected from award-winning volumes, they will move, surprise and console new parents everywhere.

ABI CURTIS, 2023

CONTENTS

NAOMI BOOTH

What is tsunami?

GAIL MCCONNELL

Talk Through the Wal

Now

Untitled / Villanelle

An Apple Seed

MALCOLM TAYLOR

To be where I am not

LIZ BERRY

The Other Mothers

Godspeed

Princes End

Blue Heaven

RACHEL BOWER

Flight

Continue on Loop

RUTH CHARNOCK

three tarot cards for the new mother

ABI CURTIS

September Birth

Ultrasound

On my son, falling asleep

Water Birth

JENNIFER COOKE

Inside the Eye

PAIGE DAVIS

This Too Will Pass

JANINE BRADBURY

Meridian

Stranger Days

Jellyfish

ELIZABETH HOGARTH

Animal Body

Shark Tooth

Injured Bird

SYLVIE SIMONDS

The bonds of love

ALEX MCRAE DIMSDALE

Bath

Disaster

Feeding the Baby

Things I have removed from my baby’s mouth

Covenant

DAISY HILDYARD

Waste

REBECCA GOSS

Other Mothers

CALEB KLACES

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction

SANDRA SIMONDS

Bikram Yoga

Lace Clouds over House over House over House

Exploding Florida

TOMMY BRAD

Expectant father

Author biographies

Permissions

About The Emma Press

Also from The Emma Press

What is tsunami?

Naomi Booth

In the beginning, there were no words. You lay back in the hospital bed, stunned. The midwife went about her business in the background. There were low murmurs in the corridor beyond you. Cries torn from other women, at the dark peak of their own labours. And here, handed onto your chest, flesh incarnate: silent, waxy lozenge of an infant.

There were no words as the baby slept, hot and larval, in the plastic box beside you. The ward was empty, except for the two of you. Your own small movements – tentative steps towards the bathroom, which brought fresh blood, the rearrangement of the baby’s blanket – were muffled and sacred.

No words, on that first night when they let you take the baby home and you lay her down beside you in the bassinet. Of course not. What were you expecting? An infant who exited the womb trilling with speech? Of course not. But still, it was unnerving. This absence of language. In those first nights, deep in the winter, when you swaddled her and tried to teach her to sleep, and you listened through the quiet hours to the bizarre, guttural sounds that came as she cleared her throat and lungs.

No one had told you that an early baby is less like something new, and more like something ancient and broken. Dark-sea fish, dredged from the Midnight Zone, sputtering water. Cawing pterodactyl of a baby.

The baby feeds incessantly through those long nights. The baby feeds and feeds and she rockets up the percentiles for weight. Her arms and legs uncoil and her belly fattens and she no longer looks like an injured relic. Her body writhes with the desire to move. She wants to be near to you, always. She mewls when anyone else holds her. The baby’s father grows angry at his redundancy. Then he is elsewhere.

The baby learns to focus her eyes on you – and there is an ardency in her gaze then that makes you think of locked-in syndrome.

When the baby first laughs it is a bleat. It is a hard burst of joy fired out into the world, surprising you both, and it finally breaks your fear of her.

Then she is singing to you. Before she can speak, she babbles in long, tuneful patterns – la da da da da la la la, ma ma ma ma, da da da, ow wow ow wow bow wow wow, row row row, uh-ooh uh-ooh uh-ooh uh-ooh – her frequent song of accidents – which will make it impossible for you to remember her first words, because they emerge and recede, emerge and recede, back and forth in a wash of sound, until one day she is saying quite distinctly to you, pointing to your plate, Mama, Mama, Isla eat, and you are elated at the ring of her voice, sweet and forceful, and you are sorrowful too at the loss of her peculiar sonar.

Still, she makes these new words her own: I got the chicken pops. Baby is mines. I live on planet erf. The cow is milking out some drink for its baby. Oh, it’s breezing. The sky is winding again. That’s the porcupine tree. What if there’s none breakfast? Let’s cook it in the hotenator. You’re a naughty clogs. I will do it NONE ways. Stop tickling – I’ll be egg-scrambled. It’s the earringest day. Pretend I’m a little girl that’s got none eyes. Morer. Do it to infinity. Persons shouldn’t run on roads. This day is it Monday? On the threeth time, I’ll stop. I am desperately Santa. I’m save-the-daying.

She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire. She names her favourite rabbit, Cunt. Or sometimes, Cunty-wunty.

You do not correct her speech. You longed for a shared language, and then you find that you cannot initiate her into its rules.

There are certain words that you dread hearing her say. The first is money. She says it one evening just before her second birthday – you are walking to the supermarket, and you search for a coin to give to a busker who is playing Christmas carols. Isla give money, your baby says. Mu-nee. You dread the way it will become as concrete to her as sky and cat and gate. Mu-nee. Mu-nee.

She will come home with new phrases each time she visits her father. Granny has eyes in the back of her head. The new doggy is driving him crackers. She will learn a whole new idiom from school. Other people’s phrases will ring, precocious and uncanny, in her voice: Adi had to go to time-out because he made some poor choices. That is CLASSIC. I’m not impressed with your behaviour. No offence. I’m just, like, having a seriously bad day.

You know that she will pick up bad words. You find that some of your friends moderate their language around her, and others cannot. He’s such a dickhead. Excuse my French. But he is. Two older girls at after-school club will teach her to say fuck (What is cough backwards? Ha ha). She uses her phonics to sound out the word S-E-X, which has been written in Tipp-Ex on a climbing frame at the park. But none of these words is as incongruous in her mouth as that first bad word, jangling there: mu-nee, mu-nee.