2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

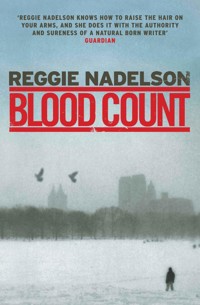

As the celebrations of Barack Obama's presidential victory draw to an end in the social melting pot of Harlem, New York, an old woman's death reveals deceit, racial tension, and city corruption... In New York's Harlem, every street is steeped in history, and the music of jazz legends plays in the memories of its residents. Artie Cohen could feel at home here - if he wasn't on the trail of a killer intent on erasing the past... An elderly Russian woman is found dead in her apartment, and Cohen finds himself in the centre of a violent debate between city developers and an older generation of Harlem tenants. Not to mention the tensions between himself, his old girlfriend, and her new, younger lover. Meanwhile someone in these once-violent streets is intent on hauling Harlem into the twenty-first century, no matter what it takes...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

BLOOD COUNT

Reggie Nadelson, journalist and film-maker, is the author of nine novels featuring the New York detective Artie Cohen. Her nonfiction book about the singer Dean Read, Comrade Rockstar, is being filmed by Tom Hanks and Dreamworks. She divides her time between London and New York.

ALSO BY REGGIE NADELSON

Artie Cohen Series:

Londongrad

Fresh Kills

Red Hook

Disturbed Earth

Sex Dolls

Bloody London

Hot Poppies

Red Mercury Blues

Somebody Else

Comrade Rockstar

BLOOD COUNT

REGGIE NADELSON

First published in the United States of America in 2010 by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York.

This trade paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Reggie Nadelson 2010

The moral right of Reggie Nadelson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84354 836 2 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 307 9

Printed in Great Britain Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Justine with love

Until last week the Red Cross, acting on orders from the services, refused to accept blood from Negro donors, although there is no physiologic difference between Negro and white blood plasma. Negroes, proud of Dr. Charles R. Drew who headed the Blood for Britain service, protested. Negro blood donations are now accepted, but the plasma will be segregated for exclusive use of Negro casualties.

Time, February 2, 1942

With many thanks to Norman Skinner, for telling me about Sugar Hill, its grand buildings and the history of the area; to Curtis Archer, for walks around the neighborhood and much more; and to Frank Wynne, for sorting it all out.

CONTENTS

Harlem, November 4, 2008 — Election Night

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Inauguration Day, January 20, 2009

Harlem, November 4, 2008 —Election Night

On a dark side street in Harlem, a silver van suddenly appears out of nowhere. Its wheels spinning, it seems to move with a life of its own, down the empty street, past the quiet brownstones and the old trees shedding their leaves.

I’ve been driving around for a while, looking for a place to park. Election night. A balmy Indian summer night in November. The sounds of the city getting ready to explode with joy, especially here in Harlem. Overhead, long beams from the arc lights on 125th Street play on the sky, the night lit up like day.

From somewhere close by comes the noise of celebration: shouting and laughter, fireworks, sparklers, music. From someplace, music—R&B, rap, Dixieland, all-enveloping—drifts through the open window of my car as I turn into 152nd Street, see an empty spot, cut across the street to grab it.

It’s tight. I back in sharp as I can, trying to fit my ancient Caddy, big boat of a car, into the space, and it’s only then I notice the van.

It comes from around the corner, comes up behind me after I’ve parked, I think. Gathering speed, it passes me, rolling down the hilly street toward Harlem River Drive.

Up here in Sugar Hill, on good days, if you’re high up in a tall building, you can see down the broad boulevards to the midtown skyline, almost down to Ground Zero, the hole in the city that’s still empty after seven years.

If I hadn’t found a spot to park that night, if I’d just given up, gone home, watched the election returns on TV, maybe none of it would have happened—not what happened then, not what followed six weeks later.

Parked now, I watch the van roll, seemingly out of control, as in a dream.

It’s new, a slick new Ford just out of a showroom, probably bought cheap now everything’s hitting the skids, car dealers selling off what they can, waiting for letters from Ford or Chrysler, or GM, telling them it’s all over, the good days gone, you’re done for, forget the ten, twenty, thirty-seven years we’ve been in business together.

Stop!

Why doesn’t the driver stop?

I can’t see a driver. It’s as if the van’s driving by itself, nobody in it, just a silvery box on wheels hurtling down to the river.

Maybe it’s the booze. I’ve been out drinking all evening, getting up enough nerve to come here, find a place to park, go over to the club on St. Nicholas Avenue. Is it the booze, a hallucination, this driverless ghost van that rolls by me faster and faster, in and out of the white pools cast by streetlights on a dark Harlem street?

But I know it’s real. I watch until it disappears around a corner as fireworks explode overhead.

SATURDAY

CHAPTER 1

Who died?”

The night when I finished a case, closed it up, got the creep who killed pigeons in the park for pleasure—and the homeless guys who liked to feed them, I went to bed early, spent a luxurious hour in the sack drinking beer and watching a rerun of the Yanks’ 2000 World Series win on TV.

As I tipped over into sleep, I realized I’d forgotten to turn off my phone. When it rang a few hours later, still mostly asleep, I ignored it, until the voice on the answering machine crashed into my semiconscious brain.

“We got a dead Russian. Get yourself over here,” said the voice, and I wasn’t sure at first if it was real or I was trapped in that nightmare where you’re buried alive, pushing up on the coffin lid, hearing a phone ring, unable to get to it.

At the foot of the bed, the TV was still on—pictures of Obama in Chicago—and I realized I was safe at home in downtown Manhattan, and then the phone rang again. It was only Sonny Lippert.

“Who died, Sonny?” I was pissed off.

“Didn’t you get my message? I told you, a Russian,” he said. “Get your ass over here, man.”

“Not now.”

“Now,” he said. “Right now. My place.”

“It’s the middle of the night.”

“Listen. Friend of mine uptown in Harlem, he needs some help, right? One of his detectives found a dead guy up in his precinct with some kind of Russian document stuck to him, skewered with a knife, like a shish kabob. He’s asking can I get it translated. Asked if I could call you.”

“Where is it?”

“What?’

“This document?”

“I have it.”

“So fax it over.”

“I want to do this in person,” said Sonny, and suddenly I knew he was lonely and wanted company.

“He’s white?”

“Who?”

“The dead guy.”

“Why?”

“You mentioned Harlem.”

“I told you, man, he’s Russian. Probably Russian.”

Still naked, I went and looked out the window and saw the light on in Mike Rizzi’s coffee shop. “I’ll buy you coffee, OK? Rizzi’s place,” I said.

I was surprised when Sonny said OK, he’d come over, couldn’t sleep anyhow. Sonny Lippert had been my boss on and off for a long time, right back to the day when he picked me out at the academy because I could speak languages, or at least that’s what he always says.

These days I humor him because of the past. He still drives me crazy some of the time, but we’re close now. He helped me with some really bad stuff last summer. When Rhonda, his wife, is away, he sits up alone until dawn reading Dostoyevsky and Dickens, listening to Coltrane, drinking the whiskey the doctor says will kill him.

Shivering, I went back to my bedroom. I yanked on some jeans and a sweatshirt, shoved my feet into a pair of ratty sneakers, grabbed a jacket and my keys, and headed downstairs, where it was snowing lightly, like confetti drifting onto the deserted sidewalk.

Who was dead? Some Russian? All I wanted was to go back to sleep.

* * *

“Morning,” a voice said, as I walked out onto the street, and I looked up and saw Sam, the doorman from the building next to mine. It was also an old loft building that dated back to the 1870s. But the owners had transformed it into a fancy condo—marble floors, doorman.

A black guy in a good suit, Sam was a presence on the street now. He was a quiet man. Didn’t say much, though once in a while we compared the stats of our favorite ballplayers. I said hi and went across the street to Mike’s coffee shop.

When I tapped on the window, Mike looked up from behind the counter. He grinned, unlocked the front door, waved me to a stool. There was fresh coffee brewing. Some pie was in the oven. It smelled good that time of morning. From the ceiling hung a string of green Christmas lights.

Mike Rizzi pretty much runs the block: he takes packages, watches kids, serves free pie and coffee to local cops on patrol.

In New York, everybody has a coffee shop, a bar, a restaurant where they hang out. It’s the way our tribes set themselves up, claim their piece of territory. To eat, I go over to Beatrice at Il Posto on East Second Street; to drink to my friend Tolya’s club in the West Village, or maybe Fanelli’s on Prince Street.

“What’s the pie?” I said.

“Apple,” said Mike. “You’re up early, man.”

“Can I have a piece?”

He was pleased. Mike’s obsessed with his pies.

“Deck the halls with boughs of holly,” came a voice over the sound system Mike rigged up years ago.

“Who the fuck is that?”

“Excuse me? That,” he said, “that is Nana Mouskouri, the great Greek singer.” Mike, who’s Italian, is crazy about the Greeks. Over the ziggurat of miniature boxes of Special K, on a shelf against the back wall, he keeps signed pictures of Telly Savalas, Jackie Onassis—he counts her as an honorary Greek—and Jennifer Aniston. “You know her real name is Anastasakis,” Mike says to me about once a week.

“’Tis the season to be jolly . . .”

“What are you doing around at this hour?” Mike looked at me intently. “You just got home from some hot date? You found a nice woman yet, Artie?”

“Sonny Lippert. Needs me for something.”

“Jesus, man, I thought Lippert retired.”

I ate some pie. “That’s really good, Mike.”

“Thanks. So, you ever see her?”

“Who?”

“Lily Hanes. You could bring her over to me and Ange for supper. Ange always says, ‘When’s Artie going to marry Lily?’”

“Sure.”

“What, you met her, like, ten, fifteen years ago? I know you’ve dated plenty of women, and we liked Maxine and all when you got married to her, but you weren’t the same with her like with Lily.” Mike was in a talkative mood.

For ten minutes while Mike pulled pies out of the oven and set them on the counter to cool, while I drank his coffee, we exchanged neighborhood gossip. I agreed to go over to his house in Brooklyn—he drives in every morning, around two a.m.—for dinner. But all the time we were making small talk, I could see there was something on his mind.

“What’s eating you?”

“Nothing, man.”

“You pissed off because McCain didn’t get in?”

Mike’s a vet, served in the first Gulf War, volunteers at the VA hospital. McCain’s a god to him.

“I got over it, more or less. It was that broad’s fault, Palin. Geez. Who invited her to the party?” Mike looked over my head toward the door. “You got company,” he said.

CHAPTER 2

Wrapped in a camel hair coat, Sonny Lippert took off his brown fedora and climbed on the stool next to mine. His hair was all gray now. He had finally stopped dyeing it. He tossed a sheet of paper on the counter in front of me and greeted Mike, who brought him a mug of coffee. “Anything to eat, Sonny?”

“You got a poppy bagel?”

“Sure.”

“Yeah, so can you do it well toasted, with a little schmear, but not too much? OK?”

“You got it.” Mike reached for some cream cheese.

I picked up the piece of paper—it felt thin and greasy, like onionskin—and when I unfolded it, I saw it was printed in Russian. “This is what you called about?”

“Yeah, man, I need you to translate it, Art. OK? They found it stuck in his chest with a knife, like I said, right near his heart,” said Sonny, pointing at the paper. I saw the edges were brown from blood.

“Where’d they find him exactly?”

“Harlem, up by the border with Washington Heights. Church cloister. Half buried, dirt all over him.”

Mike put a plate down in front of Sonny. He picked up the bagel, spread the cream cheese on it, and bit into it. “Nice,” he said to Mike. “Thanks.”

“They whacked him before they buried him?” I said.

“They cut him up good, with a curved boning knife, it looks like, same as they used to stick the paper to his heart.”

“You said he was still alive when they buried him?”

“I said maybe.” Sonny ate another bite of his bagel.

“Who told you?”

“An old pal name of Jimmy Wagner, he’s the chief of a precinct uptown, the Thirtieth. One of his homicide guys found this guy a couple days ago. I think. I think Wagner said a couple days. He thinks it’s mob stuff. Drugs, maybe. Some kind of extortion.”

“Why’s that?”

“He didn’t say, just asked for me to get him a translation,” said Sonny. “Just read it, Art, OK?”

“Don we now our gay apparel, fa la la la la la la la la . . .”

“What the fuck is that music?” Sonny said.

“Mike likes it. She’s Greek,” I said. “The singer.”

“Yeah, right. Just translate the fucking Russian,” he said. “Please.”

I gulped some coffee. I put on my glasses. Sonny was amused.

“They’re just for reading, so shut up,” I said.

While I looked at the blood-stained paper, Sonny made further inroads on his bagel. Mike poured him more coffee. I read, and then I burst out laughing; I couldn’t help it. This was stuff I knew by heart, but you would, too, if you’d grown up in the USSR, like I did. I didn’t leave Moscow until I was sixteen, and the stuff had been drilled into me like a dentist going down into the roots.

“You find it funny, Art? It’s a joke?”

“Yeah, I so fucking do.” I read out a few lines.

“In English, for chrissake.”

I read: “‘Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.’”

“Jesus,” said Lippert. “It’s the fucking Communist Manifesto.”

“Yeah, your parents would have appreciated it,” I said. Lippert’s parents had been big Communists back in Brooklyn—it’s part of Sonny’s history; it never leaves him. Now, he stared at the paper and shook his head, deep in some memory of childhood.

“Does that help?” I said. “Is that it?”

Reaching into his coat pocket, Sonny took out two pictures and tossed them on the counter and said, “Take a look at these.”

In one photo was a dead guy on a slab at the morgue. The second was a close-up of the guy’s upper arm where there were some tats, Russian words circling his bicep.

“Same guy as they found the paper on?”

“Yeah,” said Sonny.

Naked, the dead guy had a huge upper body, heavily muscled arms, a slack face. A lot of Russians who work security in the city were once Olympic weight lifters, though I’d picked up at least one hood who’d been a nuclear physicist. Times change.

What were you? I always ask them. What were you back then, before the empire collapsed, before everything changed?

“What about the tats?” said Sonny.

I held up the picture.

“Jesus,” I said. “I never saw Russian tats like this, but it goes really well with what’s on the paper.”

“Yeah? What?”

“‘Workers of the World Unite. You have Nothing to Lose But Your Chains,’ you know that one, right, Sonny? I mean, ask yourself, is this guy the last crazy Commie true-believer left on planet Earth, except for maybe a few elderly ladies holding up pictures of Stalin on the street in Moscow? Maybe he belongs to a gang of old Commies. Maybe he strayed, turned capitalist, whatever.” I yawned. “I’m going back to bed.”

“You’ll help me with this one, won’t you, Art?” Sonny asked. “You could do me a favor and drop in on Jimmy Wagner.”

“What’s your interest? You’re retired. What do you want this for?”

“I’m consulting on certain cases that come my way.”

I saw now that Sonny was looking thin, old, his face lined.

“You feel up to working?” I was worried. Truth is, I love the man.

“I’m taking a few things on.”

“Why’s that?”

“Why’s anyone hustling right now? Tough times.”

“You have your pension, right? You told me you had some investments.”

He stared down at the remains of his breakfast.

Once upon a time, Sonny Lippert was the most connected guy in the city. He could raise anyone on a dime. You’d say, Sonny, I need a lawyer for a friend, I need somebody in forensics, a contact with the Feds, and he’d say, No problem, Artie, man, just give me a few minutes.

He had to be in bad shape financially. The meltdown was killing the city. Madoff had been arrested, but I didn’t figure Sonny for a big enough player to have put his money with the bastard.

“Sonny?”

“Just say I’m doing some consulting work, OK? Can we leave it at that, Art? OK? Please?”

“Sure.”

Sonny got up, put his hat on, tossed a five on the counter, thanked Mike for the bagel and coffee. “So I’ll figure on hearing from you by the beginning of the week, right? Just plan on working with me a couple days, maybe more, right, man?” he said. “And Artie?”

“What’s that?”

“Answer your phone.”

I went home, got into bed. Warm under the covers, drifting off to sleep, I forgot about Sonny’s case. I’d left the answering machine on again, too tired to bother. When it rang, I said out loud, “I’m asleep.”

The phone rang again. The answering machine clicked on. I was sure it was Sonny, and I yawned. And then I heard her voice. I grabbed for the phone as fast as I could.

“Artie? Are you there? Pick up the phone, please, Artie? I need you. Please. Hurry.” It was Lily.

CHAPTER 3

I need you.” Lily’s voice echoed in my ear as I got in my car.

I tried playing back what she had said, but I knew from her tone she must be in big trouble. I was still groggy with sleep, and all I had really heard was that she wanted me to hurry. I looked at the road. Saturday morning, early. No traffic.

I’d scribbled the address, in Harlem, on a scrap of yellow paper I put on the dashboard. 155th Street. I drove too fast, breaking the speed limits on the FDR.

Everything was gray, the tin-colored river where chunks of ice had formed, the buildings on the Queens side of the East River, everything except the red neon Pepsi sign. It was cold. I turned on the heater and put the radio on for the forecast. Snow. Fog. Cold. Sleet fell on my windshield.

I drove. I tried Lily on my cell over and over, but she didn’t answer. The only time I’d seen her in a year had been six weeks earlier, election night, the Sugar Hill Club in Harlem.

That night in November, when I see her, she looks wonderful. Her red hair sticking out from under a gold cardboard tiara, Obama’s name spelled out on it in glitter, Lily is wearing a white shirt, collar turned up in her jaunty way. She’s laughing. She doesn’t see me at first.

“Lily?”

“Hi, Artie,” she calls out to me, spotting me near the bar. “Hi,” she says, smiling, and then, for a moment, she’s swept away into the crowd.

This is why I’m here. This is why I drove uptown, why I had jammed my car into the tight spot on 152nd where I saw the silver ghost van.

I knew she’d been working on the Obama campaign, living uptown in a friend’s apartment. So when my pal Tolya Sverdloff had said, “Let’s go to Harlem election night,” I was OK with it. “I’ll meet you at the Sugar Hill Club,” I had said. I’d been here with Lily once or twice to listen to music. I figured she might show up.

In the club, the tension is electric, everybody waiting for the results. In the club I see white faces, black, Latino, Asian. People are yakking in Russian, Italian, French. Tonight everybody is a believer. Once Obama is elected, everything will change, people say. If it happens; when it happens. Soon.

The results are coming in, slowly at first. Inside the club, the TV hangs overhead like some ancient oracle, and with every win, the crowd turns to look.

Yes we can!

“Lily?”

Almost a year since I’ve seen her. It’s a year since we agreed to stay away from each other. No calls. No e-mails. I’ve kept tabs on her as best I can. We know some of the same people.

For a while I went to bars and coffee shops I knew she liked. Sometimes I went past her building on purpose and felt like an idiot standing on the corner of Tenth Street, watching out for her.

How long have I known her? Almost fifteen years, on and off.

The only thing I’d had from her all year was a handwritten note when Val died. Tolya’s daugther Valentina died and Lily wrote to me. Just that once. Only then.

Now, Saturday morning driving through the gray city dawn, sleet coming down on my windshield, Lily, her desperate phone call earlier, election night, were all rattling through my head. Like a maniac, I drove to Harlem, dialing her phone number over and over, hurrying to see her, to help her. Lily needed me.

“Artie? You knew I’d be here, didn’t you?” Lily says when she spots me at the club on election night. She’s close enough I can smell her perfume. “It’s wonderful, isn’t it?” She gestures at the TV. “I mean, if we win.”

“You’re superstitious?”

“Yeah. I’m not hatching any chickens before they’re cooked.” She laughs. “That’s not right, is it? Oh, God, I’m so happy. Hello, Tolya, darling,” she says, hugging him as he appears, diamond Obama button blazing on his black silk shirt, magnum of champagne in his hand, pouring it in her glass, in mine, in his. Lily gulps her drink.

“God, I wish they’d hurry the fuck up.” She glances at the TV screen. “So you guys thought I’d be here?”

“Luck,” I say. Lily smiles. Tolya laughs. He knows I’m lying, knows I picked this joint because I thought Lily might come. He keeps his mouth shut. We’ve been best friends a long, long time.

Suddenly, the noise in the club dies down. There’s a sudden hush. One more state. He’s almost in, somebody whispers.

The anxiety is so solid it forms a sort of invisible shelf everybody seems to lean on. We’re glued to the TV. Lily clutches my arm. I smell her perfume again. Joy. It’s perfume I gave her.

“What time is it?” somebody calls out. “Eleven,” somebody yells back. The bartender gets up on top of the bar so he can see better. In one hand is a red-and-white-checked dishcloth. In the other, a martini glass, as if he was in the middle of making a cocktail. He stands there, suspended, waiting.

As I drove uptown on my way to Lily that Saturday morning, the weather guy on 1010 WINS was reporting lousy weather—snow, cold, sleet, airports shutting down, flights cancelled.

Sudenly, I skidded. For a few seconds I was out of control. Like the silver van on election night.

I got through it, kept heading north, trying to get to Lily as fast as I could. Where was she again? 155th Street? I knew she was in big trouble. I had heard it in her voice. Call me, I yelled into the phone, even though I was alone in the car.

I was heading for a part of town I didn’t know at all. It made me edgy. If something went wrong—a crime, a death, an accident—I’d be a white cop in a black neighborhood at the other end of the city, where I didn’t know anybody, the Saturday before Christmas with a storm coming. Last time I’d been uptown was election night and that didn’t count, that had been a night out of real time when the whole city had dropped its tribal attitudes and celebrated together.

Maybe I should call somebody, make some kind of contact in case I needed help, I thought. But until I knew what was wrong, I didn’t want to involve other people. Maybe Lily was just unhappy. She wouldn’t call me for that. Would she?

I turned the radio up. The news was all bad. Financial shit, the system coming apart, Madoff’s arrest. The election, the blaze of optimism, the joy, already seemed a lifetime ago.

“We did it!”

Eleven o’clock. Eleven p.m. Somebody yells it out: “He’s in!” The club goes nuts. Somebody pounds out “Happy Days Are Here Again” on the piano. Up on the screen, I can see people going crazy, not just in New York, but in places like Iowa! Iowa!!

Everybody is hugging and kissing, we’re all drunk, the bartender pops corks on bottles of pink champagne, somebody hands me a huge glass of bourbon. A girl in a silky red dress jams an Obama hat on my head and kisses me on the mouth. She’s drinking flavored vodka; she tastes like pears. Outside, cars are honking, people singing. Inside, everybody is yelling, crying, hugging, singing, high-fiving.

Tolya, bottle in one hand, is dancing with a pretty woman almost as tall as him, in a silvery top, silk pants, high heels. A girl who looks like Beyoncé—at least she does to me, drunk as I am—bumps into me, and apologizes and laughs, and Tolya pours her some wine, too, and she says, “It’s sweet, isn’t it? Tonight it is so sweet.”

“Where were you on election night 2008?” people will ask, the way they still ask each other about 9/11 or about the day JFK was shot. When I was a kid in Moscow, older people sometimes asked, Where were you when He died? and they meant Stalin. Where were you?

But this time, this night, we’ll remember it differently, this lifechanging event. We did it!

On the TV, there are all the faces, people crying, older black people unable to stop crying. There’s Jesse Jackson in Chicago, face swamped with tears. Enough to break your heart.

“We want Obama,” a guy near me in the club shouts. He says something in Italian. In English he adds, “Fuck Berlusconi, we want an Obama.” An Irish guy is hanging all over me, moaning, “I love this place. I love you guys.”

“Now I can stay in America,” says Tolya. He’s never loved America the way I do, but tonight it’s different. He hugs me. “Now I can stay here.” In Russian, he adds, “Maybe I buy nice house in Harlem. Become black Russian.” He laughs and can’t stop.

I put my arms around Lily. I can smell her hair, feel her against me. I kiss her. She doesn’t seem to mind, maybe because everybody is kissing, and for a moment, she’s with me again, and I’m lost.

“‘Where were you that night?’ We’ll say that, won’t we?” she says, half to herself. “We’ll be able to say to each other, ‘Where were you that night?’ And we’ll be able to say, ‘I was there. I saw him elected.’ We did it.”

“I was thinking the same thing.”

And then Lily is pulled away from me, dancing now with a good-looking black guy, a young guy.

They’re holding each other tight on the floor, and I tell myself it doesn’t mean anything, that tonight everybody’s dancing, everybody’s in love, it doesn’t mean anything at all. Does it?

For a second I lose sight of her, then she surfaces near the bar, her back to me.

I think to myself: If she turns in my direction in the next five minutes, I’ll go to her. If she turns around, I’ll go over, I’ll tell her how I feel.

But she doesn’t. She doesn’t turn around.

By the time I got off the Drive, the snow was coming down heavy, and I took a wrong turn. I found myself on the Harlem side street where I’d parked on election night, then turned the car around. For a second or two, I was lost. I felt uneasy. The streets were empty.

Finally, I pulled into Edgecombe Avenue. I found Lily’s building. Over the front door a plaque read THE LOUIS ARMSTRONG APARTMENTS. I looked up. The tall building was made of old brick. From a second floor overhang gargoyles—grotesque stone animals—leered down at me. The snow had settled onto the creepy figures.

I got out of my car, left it near the front door, and ran up the steps to the building, bumping into an elderly man in a tweed coat and cap, who muttered at me. A woman trying to get a little girl zipped into a pink jacket looked up at me and looked pissed off, maybe because I was parked in a delivery zone, or maybe she didn’t like my looks. Or my color. Dog walkers emerged from the building, one of them stopping, fussing with her hand to get the snow off her shoulders. Except for me, everybody was black.

I dialed Lily again. No answer. Anxiety, the kind that feels like a gust of icy wind on the back of your neck and along your spine, suddenly got to me. I stopped for a second, then I went inside.

CHAPTER 4

Red hair held back with a rubber band, face white, Lily looked frightened. Green sweatpants, an Obama shirt. She was waiting for me as I came out of the elevator on the fourteenth floor.

“God, I’m so glad you’re here,” she said, taking hold of my sleeve. “Thank you for coming.” Her voice was flat, but she was shaking. With cold? With fear? She led me down the long corridor, stopped in front of a door marked 14B and hesitated.

“This is your place?”

“Yes.”

“Let’s go inside. It’s cold.”

“No. Across the hall.” Lily gestured to the door opposite hers.

“What is it?”

“Come with me.” She unlocked the door. We went into the apartment.

“Whose place is this?” I said.

The woman lay on a worn brown velvet sofa. Lily, who had locked the apartment’s front door behind us, pulled back a purple shawl to reveal her face.

“She’s dead, isn’t she?” said Lily.

I felt the woman’s neck for a pulse. “Yes.”

“I didn’t know what to do. I never saw a dead body, not somebody I knew. Wars and stuff, but when you’re a reporter, it’s different. I thought I should cover her face.”

“You did the right thing.”

“She was my friend.” Lily shivered. The room was freezing. “Who left the terrace door open?” Lily asked nervously.

I went to shut the terrace door, where heavy silk curtains the color of cranberries—that Russian color somewhere between wine and blood—billowed in the bitter wind. When I turned around, Lily was staring at the dead woman.

“She always said she could only sleep in a cold room because she was Russian,” said Lily.

“Who is she? ”

“Marianna Simonova. She was my friend.” Lily put her hand on the oxygen machine that stood near the sofa. I had seen one like it before. The oxygen tank was enclosed in a cube of light-blue plastic. It stood on wheels. A coil of transparent tubing ran from the tank to the woman’s nose. The oxygen was still on; it sounded like somebody breathing.

“I left it like that,” said Lily. “I didn’t want to touch her.” She started to cry silently.

“She was sick,” I said.

“Yes.” Lily stumbled a little, moving back from the sofa. I got hold of her hand to keep her from falling.

Her hand was ice cold. I rubbed it to make it warm. I could feel the electricity between us even now. It had always been like that with Lily and me, and I knew she felt it too. Abruptly, she pulled her hand away.

“I shouldn’t have asked you to come,” she said. “It’s not fair.”

“I’m glad you called. Talk to me.”

“Marianna was so sick, and I couldn’t help her.”

“What with?”

“Her lungs were shot. I think her heart couldn’t take it. She drank. She smoked like crazy. You can smell it everywhere.”

I looked around the room with its high ceilings and fancy plaster moldings. The building must have gone up around 1920. The apartment needed a paint job. The yellow walls were grubby. The stink of cigarette smoke was everywhere; it came off the furniture, shabby rugs, the red silk drapes, off the dead woman.

“What should I do?” said Lily.

“Tell me what’s going on. You said she was your friend.”

“Help me.” Lily sat down suddenly in a small chair with carved wooden arms; she sat down hard, as if her legs wouldn’t support her.

I asked if Lily knew who the woman’s doctor was.

“What for?”

I told her somebody had to sign the death certificate. She said there was a guy in the next-door apartment who was a doctor. Maybe he could sign it. “They were friends,” Lily said. “Him and Marianna.”

“Didn’t she have her own doctor?”

“Of course. Sure.”

“You have a name?”

“Why?”

“It’s better if somebody who was taking care of her signs the certificate,” I said, and wondered why Lily was suddenly wary.

“Lucille Bernard,” she said finally. “Saint Bernard, Marianna called her. She could be pretty funny. She was funny.”

“You met her? The doctor?”

“Yes.”

“You have a number?”

“I took Marianna to an appointment once or twice,” Lily said. “At Presbyterian. Bernard’s office is in the hospital. I might have the number.”

“Let’s call her.”

“Why can’t we just get Lionel? I’ll go next door and get him.” Lily’s eyes welled up. She wiped her face with the back of her sleeve.

“Lily? Honey? It was you who found her?”

“Yes.

“How come you didn’t call 911?”

“Marianna was sick. I didn’t think it was an emergency, not if you die from being sick. Was that wrong?”

“Of course not. Did anybody else see her like this? I mean before you found her?”

“Why does it matter?” she said.

“What about last night?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know why you’re interrogating me. She was sick. She just died. I’m sorry I called you out.” Lily seemed half out of her mind now. This dead woman on the sofa had obviously meant a lot to her in a way I didn’t understand.

“Come on, honey,” I reached for her hand. “Let’s get the doctor’s number.”

Lily didn’t move. Didn’t let me hold her hand.

“Come on.”

“Don’t nag me.”

I sat on the floor near Lily’s little chair. “Is there something else going on?”

“I’m just sad.”

She was sad, but she was scared, too, and I had to know why. Was Lily lying? My gut told me she was holding stuff back. I switched on a standing lamp with a fringed shade. The low-wattage bulb spilled a dim pool of yellow light on the body.

Marianna Simonova’s getup was like a costume. Her head was wrapped in a purple silk scarf, she wore a white shirt with a high neck, Cossack style, a long skirt, and over it all, a heavy brown velvet bathrobe with fancy embroidery. Around her neck was a gold cross with red stones.

Her hands were clasped across her body, one of them curled in a fist. I figured she was arthritic.

It was as if she had been arranged—or had arranged herself— for death. There was no sign anyone had hurt her, no actual sign of her dying, either, except that she was dead. She was as composed as one of the icons on her mantelpiece.

Kneeling by the sofa, I saw she wasn’t so old, no more than seventy. Her face was still smooth, and it was a long, imperious, oval face with a weirdly high forehead, thin, plucked eyebrows, a skinny nose.

The fingers of her left hand were cold but still pliant. Rigor hadn’t set in yet. I touched the other hand. It wasn’t arthritic after all, just curled in a fist. I pulled back the fingers. Something she had been holding fell out. It was a horn button from a man’s jacket. I put it in my pocket.

Simonova wasn’t a victim. Was she? This wasn’t some case I was working. But I took the button anyway, and then I touched her face. The skin was soft, almost alive, like one of those dolls they sell at fancy toy shops, the kind with the creepy feel of human flesh.

On the floor was a biography of Rasputin in Russian, and a paperback, an English mystery, the kind my mother used to love, which she read secretly in her kitchen back in Moscow. She hid them in a kitchen cupboard with the potatoes. I remembered them all.

A little table near the sofa, black and inlaid with mother-of-pearl, was piled with pill bottles, a half-empty liter of cheap American vodka, a pack of Sobranies, most of them already smoked, a glass ashtray full of the butts. A small glass with water still in it had red lipstick on the rim, and there was a bottle of perfume. I took out the stopper, smelled it. From the low chair where she was sitting, Lily watched me.

“Artie?”

“What?”

“Please cover Marianna up,” Lily said. “I feel like she can see me.”

I put the shawl back over the dead woman’s face, which is when I noticed something I hadn’t seen before: the tip of the woman’s left ring finger was missing, and the flesh where it had been cut was thick with scar tissue.

“Lily?” I wanted to ask her about the finger, but she suddenly got up and left the room.

CHAPTER 5

Along with the stench of cigarette smoke in the dead woman’s apartment was a heavy flower smell. It came from dried rose petals in a brass bowl on an old mahogany table. Candles, most of them almost burned out, gave off a cloying stink, too, clove and cinnamon. When I touched one, it was still warm, the wax soft. Something else in the room stank in a different way: age or death.

Lily, who said she had gone to the bathroom, had reclaimed her seat in the little chair. I knew she needed time. I’d let her sit for a few more minutes. I didn’t ask about the dead woman’s missing fingertip, not now. Instead, I walked around the enormous room. Only half consciously, I was looking for clues. There was something wrong about Lily’s shift in mood from flat to frantic, something wrong the way the dead woman was posed on the sofa, something wrong in the way the place stank.

Across the room from where Lily sat I saw that part of the ceiling and wall were wet. A plastic sheet on the floor caught the water that dripped from the roof through the ceiling. Chunks of crumbling plaster lay in wet pools on the plastic.

A rickety card table held a gold-colored bust of Pushkin. The cracked marble mantelpiece was jammed with pictures, some framed in leather, some in silver. I reached for one of them.

“Leave it,” Lily called out. “Just leave it all, OK?”

I crossed the room to where she sat. “What is it? Lily? Honey?” I had never seen her so out of control, tears creeping down her cheeks.

All the years I had known her, Lily had almost never cried, unless you counted election night, and that was for joy. Not even when she was out reporting on the sex trade in Bosnia and was beaten up so badly by thugs she almost died. People think Lily’s remote, even cold, obsessed with her work, unyielding in her opinions. And she is. Sometimes. She has a temper. I didn’t care; I never had.

Seeing her in the sweatpants, her hair a mess, her face pale and wet, I realized that nothing mattered to me as much as being with her. Nothing.

“Hey.”

“What?”

I touched her sleeve lightly. “I’ll help you. I’ll fix it. Whatever it is.” I put my arms around her. She didn’t pull away this time.

Just come home with me, I wanted to say. Just come downtown, we’ll go to my place, I’ll be with you, I’ll take care of you. But I didn’t. I couldn’t take the chance she’d say no.

“Marianna was so sick.” Lily’s voice was barely audible. “She was in such pain.”

“What happened?”

“I sublet the apartment across the hall when I decided I was going to work for Obama over on 133rd Street. I wanted a change anyway, so I rented the place from a friend who was going to Chicago for a year,” said Lily. “A few weeks after I got here, I met Marianna in the hall. We talked. She invited me for a cup of tea. I could see she needed help, so I got into the habit of stopping by. I put out her meds every night, and made sure the oxygen was working right, and then I’d come by most mornings to check in on her again.”