2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

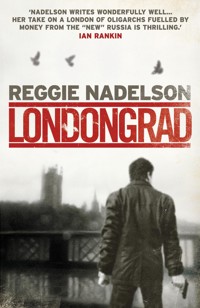

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

On the outskirts of New York, a child's swing turns gently in the breeze. Resting on it, propped at an odd angle, is the body of a young woman: naked, mutilated, and bound in silver duct tape. In the wounds on her chest, congealed blood pools in the shape of the letter T; the calling-card of a frenzied killer... Unfortunately for Artie Cohen, death is never far away. In London, where glamorous old-world émigrés rub shoulders with the hungry young zealots of Putin's Moscow, a hired gun with sadistic tastes has crashed the party. And where international espionage, business and corruption mingle, Artie might have to dance with the devil to save the life of a friend...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

LONDONGRAD

Reggie Nadelson, journalist and film-maker, is the author of eight novels, all but one of them featuring her New York detective Artie Cohen. Her non-fiction book about Dean Reed, Comrade Rockstar, is being filmed by Tom Hanks and Dreamworks. She divides her time between London and New York.

LONDONGRAD

REGGIE NADELSON

Atlantic Books

London

First published in Great Britain in trade paperback in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Reggie Nadelson, 2009

The moral right of Reggie Nadelson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance toactual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 184887 310 0

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Alice, my best friend and sister

If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.

E. M. Forster, Two Cheers for Democracy

"I'm dead," says Anatoly Sverdloff, gasping for air, lungs shot. He whispers this in Russian, in English, the crazy mixture he speaks, but stumbling, gulping to get air in, trawling for oxygen, voice so small, you can hardly hear him. He can't breathe. His heart is killing him, he says, pushing the words out in short helpless bursts.

Medics, nurses, other people crowd around the bed, a whole mob of them, shaking their heads to indicate there's no hope.

Hooked up to machines, thick transparent corrugated tubes, blue, white, pushing air into him, expelling the bad stuff. IVs stuck in his arms trail up to clear plastic sacks of medicine on a metal stand. He wears a sleeveless hospital gown that's too short.

On his back, this huge man, six foot six, normally three hundred pounds, but seeming suddenly shrunken, like the carcass of a beached whale. Only the dimples in the large square face that resembles an Easter Island statue make him recognizable.

Somewhere, on a CD, schlocky music is playing, music will help, somebody says, and a voice cries out, no, not that, put on Sinatra, he loves Sinatra. Or opera. Italian. Verdi. Whose voice is crying out? Tolya's? No one is listening.

More doctors and nurses bundled up in white paper suits like spacemen come and go. But there's no reason for it, no radioactive poison in him, why are you dressed like that? the voice says. Everybody has a white mask on, and white paper hats. Party hats. Somebody is blowing a red party whistle. People wander in and out of the room, some lost, others looking for the festivities. The guy is dead, somebody says, there's no party.

A single shoe, yellow alligator, big gold buckle dull from dust, is near the bed, just lying there. Somebody picks it up. His massive feet sticking out from a blanket are the gray of some prehistoric mammal, as if Tolya is returning to a primitive form, the disease eating him from the inside out.

And then he's dead.

He's in a coffin, for viewing, and he turns into Stalin, the enormous head, the hair, the mustache, the large nostrils, why Stalin? Why? Or is it Yeltsin? Big men. Big Russian men.

My best friend is dying, and I can't stop it, and he says, Artie, help me, and then he's dead, and I start to cry. Stop the music, I yell. Turn it off! Suddenly I have to sit down on a chair in the hospital room because I can't breathe anymore. Somebody tries to stick a tube in my nose but I fight back. The tubes trip me, I'm tangled in clear plastic tubes, falling.

He rips off the tubes, pulls out the lifelines, the IVs, and all he says is, "I knew Sasha Litvinenko. I met him, and they killed him and nobody remembers the poor bastard anymore."

Contents

PART ONE NEW YORK

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

PART TWO

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

PART THREE LONDON

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

PART FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

PART FIVE MOSCOW

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER FORTY-NINE

CHAPTER FIFTY

CHAPTER FIFTY-ONE

PART SIX

CHAPTER FIFTY-TWO

CHAPTER FIFTY-THREE

CHAPTER FIFTY-FOUR

CHAPTER FIFTY-FIVE

CHAPTER FIFTY-SIX

CHAPTER FIFTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER FIFTY-EIGHT

PART ONENEW YORK

CHAPTER ONE

From behind the bar at his club in the West Village, Tolya Sverdloff looked up and saw me.

"Artie, good morning, how are you, have something to drink, or maybe a cup of good coffee, and we'll talk, I need a little favor, maybe you can help me out?" All this came out of his mouth fast, in a single sentence, as if he couldn't cram enough good things into it if he stopped for breath.

In the streaming shafts of morning sunlight coming in through a pair of big windows, he resembled a saint in stained glass, but a very secular saint, a glass of red wine in one hand, a Havana in the other and an expression of huge pleasure on his face. He stuck his nose in the glass, he swirled it and sniffed, and drank, and saw me watching.

"Oh, man, this is it," he said. "This is everything, a reason to be alive. Come taste this," added Tolya and poured some wine into a second glass. "A fantastic Ducru. I'll give you a bottle," he said. "As a reward."

I sat on one of the padded leather stools at his bar. "What for?"

"For coming by at this hour when I call you," said Tolya, who tasted the wine again and smiled, showing the dimples big enough for a child to stick its fist in. He brushed the thick black hair from his forehead, and rolled his eyes with pleasure at the wine, this big effusive generous guy, a voluptuary. Wine and food were his redemption, he always said.

"So what do you need that you got me here at the fucking crack of dawn on my first day of vacation?" I said. "I'll take that coffee."

He held up a hand. Some opera came in over the sound system. "Maria Callas," said Tolya. "Traviata. My God, has there ever been a Violetta like that?"

While he listened, I looked at the framed Soviet posters on the wall, including an original Rodchenko for The Battleship Potemkin, and wondered how the hell he had got hold of it.

"Coffee?"

"Try the wine," he said. "You should really come into business with me, you know, Artie. We could have so much fun, you could run this place, or we could open another one, you could make a little money. Anyhow, you're too old to play cops and robbers."

"I'm a New York City detective, it's not a game," I said. "You met somebody? You sound like you're in love."

"Don't be so pompous," said Tolya and we both burst out laughing.

"Yeah, I know."

"You working anything, Artemy?" He used my Russian name.

Like me, Tolya Sverdloff grew up in Moscow. I got out when I was sixteen, got to New York, cut all my ties, dumped my past as fast as I could. He had a place over there, and one in England. Tolya was a nomad now, London, New York, Russia. He had opened clubs in all of them.

"I am on vacation as of yesterday," I said. "Off the job for ten fantastic days, no homicides pending, no crazy Russians in need of my linguistic services." I stretched and yawned, and drank some more of the wine. It wasn't even nine in the morning. Who cares, I thought. The wine was delicious.

Tolya lifted his glass. "My birthday next week," he said.

"Happy birthday."

"So you'll come to my party?"

"Sure. Where?"

"In London," he said.

"You know I worked a case there once. It left a bad taste."

"You're wrong. Is fantastic city, Artemy."

I drank some more wine.

"Best city, most civilized."

Whenever he talked about London these days, it was to tell me how wonderful it was. But he described it as a tourist might— the parks, the theaters, the pretty places. I knew that he had, along with his club there, other business. He didn't tell me about it, I didn't ask.

He put his glass down. "Oh, God, I love the smell of the Médoc in the morning, Artyom," said Tolya, switching from English to Russian.

Tolya's English depended on the occasion. As a result of an education at Moscow's language schools, he spoke it beautifully, with a British accent. Drunk, or what he sometimes called "party mood", his language was his own invention, a mix of Russian and English, low and high, the kind he figured uneducated people speak—the gangsters, the nouveau riche Russians. He taunted me constantly. He announced, once in a while, that he knew I thought all Russkis were thugs, or Neanderthals. "You think this, Artemy," he said.

His Russian, when he bothered, though, was so pure, so soft, it made me feel my soul was being stroked. Like his father spoke when he was alive, Tolya told me once. His father had been trained as an actor. Singer, too. Paul Robeson complimented his father when his father was still a student. He had the voice, my pop did, said Tolya.

"You said you need a favor?"

"Just to take some books to an old lady in Brooklyn, okay?" Tolya put a shopping bag on the bar. "You don't mind? Sure sure sure?"

He already knew I'd do what he wanted without asking. It was his definition of a friend. He believed only in the Russian version of friends, not like Americans, he says, who call everybody friends. "My best friend, they say," he hooted mockingly.

"I would go myself," said Tolya, "but I have two people who didn't show up last night. Which a little bit annoys me because I am very nice with my staff. I pay salary also tips, unlike many clubs and restaurants."

It was one of Sverdloff's beefs that most staff at the city's restaurants were paid minimum wage and made their money on tips. "I hate this system," he said. "In Spain it is civilized, in Spain, waiters are properly paid," he added and I could see he was starting on his usual riff.

"Right," I said, feeling the wine in my veins like liquid pleasure. "Of course, Tolya. You are the nicest boss in town."

"Do not laugh at me, Artyom," he said. "I am very good socialist in capitalist drag."

Tolya had called his club Pravda2, because there was already a bar named Pravda, which the owner, very nice English guy but stubborn, Tolya said, had refused to sell him. Club named Pravda must belong to Russian guy, Tolya said. English guy won't sell me his, I open my own.

Pravda2, Artie, you get it?

You like the pun, Artie? You get it? Yeah, I get it, Tol, I'd say, Truth Too, In Vino Veritas, blah blah, you're the fountainhead of all that is true, you, in the wine, I get it.

Originally, he'd planned on making P2, as he called it, a champagne bar he'd run for his friends, to entertain them, and where he would only sell Krug. He added a few dishes, and got himself a line to a supplier with very good caviar, and a food broker, a pretty girl, who could get excellent foie gras, he told me.

To his surprise, it was a success. He was thrilled. He gave in to his own lust for red wine, big reds, he calls them, and only French, the stuff that costs a bundle. And cognac. Some vodkas.

I wasn't a wine drinker. People who loved it bored the shit out of me, but sometimes Sverdloff got me over in the afternoon when the wine salesmen come around and we spent hours tasting stuff. Some of them were truly great. Like the stuff I was having for breakfast that morning.

Tolya saw himself, he had told me the other evening, as an impresario of the night. I said he was a guy with a bar.

He liked to discuss the wines, not to mention the vodka he got made for him special in Siberia that he kept in a frozen silver decanter. He went to Mali last January to visit his Tuareg silversmith. He stayed for a month. Fell in love with the music.

Sverdloff liked the idea of the rare piece of silver, the expensive wine, liked to think of himself as a connoisseur. It's just potatoes, I said. Potatoes. Vodka is a bunch of fermented spuds, I told him.

"So you'll take the books for me?" Tolya said.

"Give me the address." I finished the wine in my glass.

"They're for Olga Dimitriovna, you remember, you took some books before, the older lady in Starrett City? She likes you, she always says, please say hello to your friend. I got them special from our mutual friend, Dubi, in Brighton Beach, very good editions, Russian novels, a whole set of Turgenev," he added, and picked up his half-pound of solid gold Dunhill lighter with the cigar engraved, a ruby for the glowing tip. He flicked it and relit his Cohiba.

"Of course."

"Thank you for this, Artie, honest. It is only these books, and some wine, but this lady depends, you know?" He put his hand into the pocket of his custom-made black jeans, and extracted a wad of bills held together with a jeweled money clip. "Look, put this inside one of the books. She won't take money, but I know she needs."

I took the dough.

"I would go myself if I could," he said.

"Yeah, yeah, and how would you ever find Brooklyn anyhow?" I picked up the bottle and poured a little more wine in my glass.

"So you'll go now, I mean, you're waiting for what, MooDllo?" he said, his term of affectionate abuse, a word that doesn't translate into English but comes from "modal" that once meant a castrated ram but moved on to mean a stupendously stupid person. An asshole was maybe the right word, but in Russian much more affectionate, much dirtier. He glanced at his watch.

"What's the hurry?"

My elbows on the bar, I was slowly winding down into a vacation mode, thinking of things I'd do, sleep late, listen to music, some fishing off of Montauk, maybe ride my bike over the George Washington Bridge, see a few movies, take in a ball game, dinner out with some pals, maybe dinner with Valentina though I didn't mention it to Tolya. He was crazy about his daughter, Val, and so was I. If Tolya knew how much, he'd rip my arms out. She was his kid, she was half my age.

"Pour me a little more of that wine, will you?" I said.

"Just go."

"I hear you. I'm going."

"You'll come by tonight?" said Tolya.

"Sure."

"Good."

I was halfway out the door, when I heard Tolya behind me.

"Artemy?" He stood on the sidewalk in front of Pravda2, and held his face up to the hot sun. He waved at a delivery guy, he smiled at a couple of kids on skateboards. He was lord of this little domain, he owned it, it was his community. I envied him.

"What's that?"

He hesitated.

"You used to know a guy named Roy Pettus?"

"Sure. Ex-Feeb. Worked the New York FBI office back when, I knew him some, worked a case, a dozen years, more maybe, around the time we met, you and me."

"I don't remember," said Tolya. "Anyhow, he was in here, asking about you."

"When?"

"Last night after you left."

"Pettus? What did he want?"

Tolya shrugged. "Came in wearing a suit, said he wanted a glass of wine, didn't drink it, didn't look like a guy who knows his Pauillac from his Dr Pepper. Made a little conversation with me. Asked about you."

"What about?"

"How you were, were you still working Russian jobs," said Tolya, "How's your facility with the lingo. Doesn't ask straight out, but kind of hangs around. Tells me we met at your wedding, knows you got divorced. Pretends he is just making conversation, but what the fuck is a guy in a suit like that doing in my club? I got the feeling it was why he dropped by, wanting to ask about you."

"Why didn't he just call me?"

"What do I know? Maybe he's just some old spook who likes playing the game, what do they call it, tradecraft?" said Tolya laughing and making spooky noises and laughing some more. "Well, as my daughter says, whatevs, right?'

"Yeah, right. Last I heard Roy Pettus retired home to Wyoming."

I headed for my car at the curb. I had gotten it washed in time for vacation, and it looked beautiful, gleaming and red, the ancient Caddy convertible. I climbed in, put the Erroll Garner disc into the slot, and turned the key.

"Think about coming into the business with me, okay?" Tolya called out.

Already I was listening to the joyous music of Concert bythe Sea, but I took in what Tolya said. Every month or so, when he asked me again, more and more I thought: why not go in with Sverdloff? Why not take him up on it, a trip to London, a chance for a new life, stop chasing fuckwits who murder people? Maybe it was time.

"Don't get lost in Brooklyn," Tolya called out, grinned and waved me away.

CHAPTER TWO

If I had gone straight to Brooklyn from Tolya's, if I had not stopped at home to grab some swim shorts and call Valentina, maybe I could have avoided the whole damn thing, maybe I would have avoided the little kid, yelling and waving, mouth open in an O with a howl coming out.

By the time I saw her, as she darted into the street, I was a second away from running her down, from killing her. Sweat covered my face, ran down the back of my neck. The bag on the seat next to me fell on the floor, books tumbled out, the books I was taking to the old lady for Tolya.

I slammed on the brakes. I got out of my car in the middle of the street. There wasn't much traffic out here in this dismal corner of the city, but a few cars were honking now, and I yelled at them and grabbed her up, the kid who was yelling, and sat her down on the curb. It was a warm dry day, gusts of wind coming off the water half a mile away. Balls of newspaper and dust rolled along the nearly empty street. It was a holiday. July 4.

On the broken sidewalk out here at the edge of Brooklyn, where it butts up against Queens, I put my arm around the kid in the dirty pink t-shirt and tried to get her to talk to me.

After a while, she calmed down some, and started talking in a tiny voice and I realized she was a Russian kid. I asked her name. Dina, she mumbled, and pulled at me, and I followed her across the street, which was lined with ramshackle houses, some of the windows broken and covered with plywood and plastic. In one of the yards weeds had grown up over the skeleton of an old Mercedes. There was garbage everywhere. A desolate place, fifteen miles from the middle of Manhattan.

Dina ducked under some rough bushes. In front of us was a gate to an old playground surrounded by chain-link fencing. There was a padlock on the gate. A piece of the fence was missing and Dina got on her belly and crawled under it. I followed her into a wasteland of overgrown weeds and grass, used needles, empty bottles. It was silent, a thick, dead silence, except for something creaking, a low raw sound I couldn't identify.

The jungle gym was broken. The sandbox was empty, no sand to play in. Dina was silent now, too, she had stopped babbling, stopped talking. Then she lifted one skinny arm and pointed and I followed her gaze and saw it, a figure on a swing. It was the source of the noise, the raw creak, the metal chains grinding against the poles where the swing hung.

Wrapped in silver duct tape that glinted dully in the morning light, the figure – probably a woman – was sitting on the swing, arms tied to the chains with rope, a harsh wind moving her back and forth. Or maybe it was her own weight that propelled her as she went to and fro, back and forth, on the swing in the deserted playground in Brooklyn.

"When did you find this?" I said in Russian as softly as I could, though there was nobody else here.

"Is she dead? She is dead?" said Dina, and then suddenly broke away from me, and ran out of the playground, head down, too fast for me to catch her, a blur of skinny legs and arms and pink shirt.

I called it in, and went back to the swings.

I caught the body and held her still. She was heavy. She seemed to lean against me. I stumbled and tripped and fell on my knees. A broken bottle cut me and blood stained my ankle.

The feel of the greasy duct tape dank from humidity made me want to gag. I could feel this was flesh under the tape, that this had been a woman.

I've been a cop a long time, twenty years, more, but this was so surreal, for a second I thought I was hallucinating. I didn't know what to do, not when the body against me seemed to breathe in and out of its own accord.

Was she still alive?

From above came the sound of a solitary plane; piercing the blue sky over the city, it came in low over the Jamaica Wetlands on its way into JFK.

I had to know what was under the tape.

Holding the body still with one arm, I lifted a small section of tape off the face. The tape rasped against the skin. It had been crudely done. The tape came away easily. I touched the skin near the nose lightly, and I saw one of her eyes and thought I felt it flutter, as if it might suddenly open.

She was dead. I never was an expert on physical death but she had been on the swing a long time, far as I could tell.

Wrapped up first? Dead first?

I wanted to beat it, get out, go back on vacation, but I had to wait for help. I didn't want some other kid like Dina stumbling in here and seeing this.

Listening for sirens. Wishing I had a cigarette. Sweating in the hot sun, all I could do now was wait.

I didn't know what else to do so I sat on the swing next to her. Together, the dead woman and me, we swung back and forth, to and fro, like kids early in the morning with nobody else to see them.

Behind me was the sound of sirens, of voices, of footsteps. I got up off the swing, turned and saw them coming, a small army trooping onto the playground.

Somebody had removed the gate so the ambulance people could get through. Uniforms, detectives, forensics people, all of them streamed in. It was like a tribal ceremony, the woman wrapped in silver tape on the ground now, everyone else moving around her in a ritual dance.

I spotted Bobo Leven, a young detective who was Russian-born. I went over and told him what I knew and then I started out of the playground. Bobo tried to follow me. I told him it wasn't my case. I happened to be around, but I was leaving. He wanted my help, but I said I was sorry, I had to go, I was on vacation.

"Good luck with the case," I said finally, shaking loose of Bobo Leven, hurrying away now as a couple of photographers from forensics brushed past me to take more pictures of the corpse like the paparazzi of the dead.

CHAPTER THREE

On the wall of Olga Dimitriovna's place were three photographs, black and white pictures of children staring straight at the camera, and she saw me look at them as soon as I entered the apartment.

"Yes, you imagine these were taken by Valentina Sverdloff, isn't that right?"

I nodded.

"Please, come in, Artemy Maximovich," she said, a wiry woman about eighty, sharp as a bird, with a humorous face who was crazy about reading, especially novels. I placed the bag Tolya had given me on a table, and she took one out and admired it.

"So, tea? Coffee? A sandwich also? You are hungry, Artemy Maximovich?" She went into the tiny kitchen to prepare food.

I put my head through the kitchen door and said I'd have a sandwich with my coffee. I wasn't hungry, but I knew she was a solitary old lady who wanted me to stay a while and talk. I didn't remember the photographs.

"Valentina gave them to me, a month ago, I think."

"You know Val?"

"Of course. For a time she comes to me for her Russian lessons. But not lately. The photographs are of children at her orphanage in Moscow."

"What orphanage?"

"Where she gives money," said Olga. "I think perhaps not an orphanage but a shelter for girls. Please say hello. Please, sit down," she added.

The apartment was small, the furniture old. Olga still gave Russian lessons, she had told me, but the money wasn't much. From a radio came a Beethoven sonata.

Out of the window here on the sixteenth floor, I could almost see the playground where I'd just been. In the other direction were the nineteen brick buildings of the Boulevard Public Housing project. I could see the vast Linden Houses, too, tens of thousands of people stacked up in scores of towers and below them the tangle of urban outlands and inner suburbia, bagel stores and storefront churches, squat low synagogues, C-Town supermarkets, Chinese restaurants with bulletproof windows, makeshift mosques, Indian takeouts. And the water, the Jamaica Wetlands, the network of wild islands where water-birds congregate and the dirty strip of beach where gulls pick over garbage for their breakfast.

I love the water. I used to go out on the party boats from Sheepshead Bay and fish for stripers and blues. A few miles away from where I stood is a secret place I go sometimes, a nice tavern at the edge of the wildlife sanctuary, where you meet other cops and fire guys, Irish mostly; you drink some beers or Guinness and there's a breeze and it smells unbelievably sweet.

My phone was ringing, but I turned it off and sat with Olga Dimitriovna and ate my fried-egg sandwich and chatted in Russian. She told me there had been three muggings in her building. I told her to keep her door locked at night and the chain on, and I gave her my cell number.

"Anatoly Anatolyevich Sverdloff is a good man," she said. "He gives to everybody. Please say thank you." Olga pushed her wire-rim spectacles on top of her head, thanked me again, and offered me a glass of brandy. I refused.

"Please, come back, Artemy," she said. "And tell Valentina to come." She kissed my cheek, papery lips against my skin, and handed me a box of chocolates, which she had wrapped carefully with fancy gold paper and a red ribbon. "For Mr Sverdloff who sends me the books. You'll give this to him?"

"Yes, of course," I said.

"Tell Valentina I miss her, please."

"Is there anything else I can do for you?"

She shook her head. "But maybe I will call you for help with some of my neighbors. They are afraid."

"Of the muggings?"

"Of everything, crime, black people, of the new kind of Russians, of anything different, of a feeling that they may have to move again, or leave America. Most are legal, but they are afraid. They pull down their blinds and pray to God," she added. "Except God isn't listening. So some of us fight instead. We fight landlords. We remember how to fight. Goodbye, again, Artemy."

As I walked along the corridor of Dimitriovna's floor, I could hear classical music from behind the doors. Doors opened a crack, mostly old people looking out to see who it was, and if it was safe, and seeing other tenants looking out of their apartments, greeted each other in Russian, and fixed social arrangements for cards and tea. One elderly man held the door open long enough to take a good look at me.

"Who are you?" he said in English with a thick accent. "What do you want?" He was angry, I could see he felt I was some kind of interloper, somebody without any real business up here. Maybe he figured me for a developer.

Decades back, these high-rise towers had been built to house immigrants, forty bucks per room back then. They were almost trashed in the 1980s by gangs and guns, and people bolted their doors and rarely went out.

Now the crack dealer creeps had gone the place was threatened instead by Trump, or some other feral developer: take it over, raise the rents, blow it up, co-op it. Looked like by fall the deal would be done.

But Olga Dimitriovna and her friends weren't going to budge easy, not without a fight, not after they'd made a life, a village up on the sixteenth floor, the old-timers helping the new ones, everybody in and out of each other's apartments, sitting out on nice days on green and yellow plastic deckchairs, as if the sidewalk in front was a front porch; or making trips over to Brighton Beach to shop or eat on special occasions or maybe to the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan for music once a year.

They would resist. They would organize. If necessary, they would fight. They had survived everything else. Stalin, Hitler. Coming to America.

But even here, thousands of miles from Moscow, people were paranoid. Russia was hot as hell, in several senses, and now Putin was rattling his nukes, and people were secretly thinking: will America bend to these people? Will they cut off the stream of Russian immigrants? Will they listen to Lou Dobbs, the asshole on CNN who rants about immigrants every night? Even Russians with American passports, think: will I have to move again? Where will I go?

Near the elevator, I turned on my cellphone.

"Who is it?" I said, but the signal was dead.

I banged on the elevator door. Where was it?

Some of the tenants re appeared in the hall and watched until the elevator came and I went away. Ingrained in them was a deep suspicion, even hatred, of cops. Somehow they knew I was a cop, or suspected it. I realized I was still carrying the fancy box of chocolates and in the heat, I could smell them. I got into the elevator, feeling somebody was on my back. I opened the chocolates. I ate one. It had a nut in it.

CHAPTER FOUR

I was still holding the chocolates when I left the building, and as I got to my car, I thought I saw the kid, the Russian girl, Dina.

"Hey!"

I ran after her. Maybe I was wrong. Maybe it was the hot sun in my eyes. I ran until my lungs burned. I caught her near a wire fence that divided the street from a water-plant facility, and a stretch of filthy beach.

When she saw me, she stopped. She hadn't been running away from me.

"Why were you running?"

"I was looking for somebody," she said in Russian.

"Who?"

"Nobody."

We were outside a broken-down housing project. Some of the little yellow tiles had fallen off the façade, like scabs off a half-healed wound.

"You live here?"

She shrugged.

"You want to tell me something?"

"Yes."

I looked at her. "You're hungry?"

She nodded and I took her into a bodega on the other side of the street and bought her a ham sandwich and a Coke and a bag of Fritos and watched her eat all of it without stopping. I wondered when she had her last meal. All the time I was with her, she stared at the box of chocolate. I gave it to her. She shoved the candy into her mouth.

"Where do you live? Will you show me?"

"I have something," said Dina, clutching her fist shut.

"Show me."

When she opened her hand, she had a thin silver chain with a blue ceramic evil-eye charm in light blue and white.

"Where did you get this?"

"In the playground," she said.

I waited.

"Will you give me money for it?" She looked up at me and her eyes were like a desperate little animal.

"Why should I?"

"I got it from the playground. I got it near the swing."

"You took it from her?"

"No. I picked it up."

"How much?"

"One hundred."

"No way," I said in Russian. "No deal."

"Fifty." She was tiny and hungry and scared and an easy mark. The necklace wasn't worth five bucks.

"I'll give you twenty-five," I said and she lit up like somebody had turned a switch.

I gave her some bills with one hand while I called a friend, a good female cop I know who would come and help me get the kid to a safe place.

"I want to go home," she said.

I held on to her as best I could, but as soon as she felt me loosen my grip—I couldn't handcuff her or anything—she broke away, same as earlier, just broke free and ran like hell and disappeared among the broken buildings.

* * *

"Artie?" It was Bobo Leven, the detective who had answered the call on the playground case. He was leaning against the jungle gym smoking. I looked at the swings. The body was gone.

"Yeah, hi, Bobo."

"You got my message?"

"I got it. I'm in a hurry, so what do you need?"

"Thanks for coming."

"Yeah, sure," I said. Bobo looked anxious. "You'll do the case fine, Bobo, you'll make your name with it."

His real name was Boris Borisovich Leven, but everyone called him Bobo. He was twenty-eight and smart as hell, having finished Brooklyn College in three years instead of four, followed by his MA at John Jay in criminology. He was still living at home these days, out on Brighton Beach with his parents.

And he knew the Russkis out there as well as anyone in the city, including me. Also, his mother, who ran a little export-import business from the house—Russian embroidery, varnished boxes, cheap porcelain, that kind of shit—went back and forth a lot, so he had a handle on what was doing over there. Bobo had cousins every place: LA, London, Miami, Los Angeles, Moscow, Tel Aviv.

At six four, with the kind of long springy muscles you get if you work out right, he played good basketball. He had an accent, but he was a handsome kid with nice manners, and when I needed a favor, he was always ready.

I had worked with Bobo Leven a few times. And once, I took him out drinking with a couple of the guys, and he loved the tribal aspect of it, the fact you could say things you couldn't say to anyone else in language you could never divulge to civilians. He knew there were things that only other guys on the job understood. They liked him okay. But one of my oldest friends said to me, "He looks nice, he acts respectful, but I don't trust him much."

* * *

A couple of hazmat guys, white paper suits, yellow rubber boots, showed up and started working over the playground, taking samples of dirt, looking at their Geiger counters, whispering to each other through their masks, and Bobo, seeing them, looked nervous.

"What are they here for?"

One of the guys removed his mask and I recognized him from a job I did once. Couldn't remember his name, and he was older and heavier, but the face was the same. I went over and talked to him out of Bobo's hearing. I didn't want him getting in the way. The wind puffed out the papery white hazmat suit.

"What's going on?"

"Somebody thought the scene could be hot," said Tom Alvin, name on his badge. "They always think a scene is hot, you know, man, I mean, it's an obsession, they find a case, they send us in, and what the fuck difference does it make, you know? They're consumed, man, with the idea of a dirty bomb. They read too much shit in the papers, you know, like that spy thing over in England, what was his name, the Russian dude that got poisoned? You heard about that? Some kind of radiation shit, but it was like a couple of years ago. Man, we better all pray McCain gets elected, he's like a regular fucking war hero and if we get trouble, he's the guy." He paused. "You wanna know what they should do?"

"What's that?"

"They should stop seeing movies that got nothing to do with what's going on, all them big thrillers with nuclear shit in them, and worth nothing, nada, zero. They should spend some money inspecting container ships, and the baggage holds of all those aircraft from crazy places, how about hospital waste, how about them nuke plants that got no controls? But we don't got no money for that, right, man? It's coming, but not like this in some fucking playground, or in somebody's sushi like the guy in London. One day, it'll just come outta the sky, bang, like the Trade Center, bing bang boom!" He snorted, threw his smoke on the ground, crushed it with his foot and put his mask back on. "Artie, right?"

"Yeah."

"You working this?"

"No, just passing by."

"Didn't you work a nuke case way back in the day, out by Brighton Beach? You tracked some nuke mule who carried stuff out of Russia in his suitcase? I remember that. With some of those fucking Russkis, right?"

"Yeah," I said.

"So you think you got something here?" I gestured at the swing.

"I'm not sure. You want me to give you a call?"

I nodded in Bobo's direction. "Call him, if you want."

"What did the hazmat guy say?" Bobo asked.

"Give him your number, he'll call you."

"So would you work this with me, Artie?"

I told him I was seriously on vacation.

"I can call you for some advice?" He was polite, but I didn't feel comfortable with this guy. Maybe all he wanted was to do the case right, but there was something I couldn't explain. I wanted to get away.

"Or maybe we could have a beer together once in a while and I could talk through it with you?"

"Sure," I said, and headed for the street, Bobo following me, scribbling in his notebook fast as he could write.

Outside the playground, I leaned against Bobo's red Audi TT and wondered how he could afford it.

"Nice car," I said.

"Thanks."

"So what do you think?" said Bobo, dragging in smoke the way only a Russian guy can do it.

"I don't know," I said.

"Me either. I mean, Artie, you been on the job all this time, and who the fuck tapes up some poor girl and leaves her to suffocate in this shitty place?"

"I don't know, Bobo, I don't know who likes making people feel pain."

"You're wondering if they taped her up before she was dead?" said Bobo.

"I have to go," I said. "Keep in touch."

"A guy once told me once you get close to a case, you can't let go, isn't that right? Artie?"

"He was probably drunk," I said. "You don't know anything about me."

CHAPTER FIVE

Stacks of pink cold cuts lay on trays, little mountains of cubed cheese, orange, yellow, white, carrot sticks, candy bars, bagels, rolls, pastries that glistened, shiny under the lights, were arranged on platters, and NYPD guys in uniform were gobbling up food as fast as they could, as if they didn't know where their next meal was coming from, shoving food into their mouths, piling it high on paper plates. The long tables were set up outside the sound stage.

"Craft Services, they call it," said Sonny Lippert, my ex-boss, when I found him at the Steiner Movie Studios where the old Brooklyn Shipyards had been.

He picked up his plate and sauntered out into the courtyard, and I followed him. He sat on a canvas directors' chair and gestured to another one. I sat next to him.

I wanted his advice before I saw Bobo Leven again. The dead girl wasn't my case, it was Leven's, but I couldn't let it go. The image of the girl on the swing stayed with me like floaters that stick in your eye, float on the surface of your brain, clog your vision. Some guy had told Leven when I got close to a case I couldn't let it go, but that was crap. I was happy to turn it over to Leven. I was curious was all. I had seen the girl on the swing first and I was curious.

Or was I fooling myself? Had I become some kind of obsessive, one of those cops who can't get the smell of a homicide out of his nose?

It wasn't that I planned to work the case, I only wanted advice. Any information I got I'd pass on. Anyhow, I owed Sonny Lippert a visit. I hadn't seen much of him lately.

"So, Artie, good to see you, it's been a while," said Sonny, who was wearing a captain's uniform, the kind of dress blues guys wore to funerals. I had never in my life seen Lippert dressed as a cop. Almost all the years I'd known him, it was after he left the police force to work as a US attorney.

"What's with the outfit?" I said to Lippert who had been my boss on and off for years until he retired.

"Nifty, right," said Sonny, smoothing his navy blue jacket. "Fits me nice, right? I sucked up to the wardrobe lady, man. These people are cool. Listen, man, you want to go hear Ahmad Jamal with me in the fall, one of the last of the greats, man?" he said.

Long ago Sonny and me had started listening to music together. He still calls everyone "man", a leftover from his younger years when he hung out with jazz guys. He still listened to the music with real love.

When I was still a rookie and broke, he sometimes invited me to concerts at Carnegie Hall and sometimes to the Vanguard. It was with Sonny I first heard Miles Davis in person, and Stan Getz, and Ella.

"What the hell are you supposed to be?" I said, smiling because I suddenly felt affectionate towards Sonny.

"I'm a police captain, man," he said, buttering a roll he had on the plate on his lap. "I'm an extra. The movie I'm working. I'm a consultant. I told you. Didn't I?"

All around us real cops and fake movie cops, both, smoked and ate. One guy bit off half of an enormous sesame bagel stuffed with cream cheese and lox, tossed the other half in a garbage can and began kicking a soccer ball around the huge yard of Steiner Studios. Beyond the yard that was surrounded by a high chain-link fence, twelve, fourteen feet, was the old waterfront. With the staggering view of Manhattan and the river, once all this had been the Brooklyn Navy Yards where World War II ships were built.

"What do you know, you haven't been a cop since Shaft was in action," I kidded him, drinking my root beer.

"I sit around all day and actors come by and we shoot the shit about being a detective, and I tell them how to walk and talk, make it look real."

"How the fuck do you know how cops walk and talk?"

"It's not brain science, you know, Artie, man. One of the producers, so-called, said to me, you have that authority thing, Sonny. You got it. Teach them." He laughed. "I tell them how it is, then they go and put the girls in low-cut tops and tight pants. I mean, what female detective is going to fucking dress like that in real life? Or maybe they do now. Maybe the real ones get how they dress from the TV cops," said Sonny, heading into one of his riffs. "Truth is nobody knows what's real anymore," he added. "A lot of actual cops I know have stopped using the old lingo. Once civilians started picking up stuff from Law and Order, you know, bus for ambulance or on the job for being a cop, guys started dropping it. Hard to tell the difference, right, man? Reality and fiction, man, who can tell?"

"Jesus, Sonny."

"So you came by to chew the fat, shoot the breeze, what, Artie?"

Sonny sat back on his canvas chair and looked me over.

Small and tightly wound as clockwork doll, his hair is still black and I have to figure he dyes it because Sonny must be pushing seventy. He seems a lot younger, doesn't look much different from when he recruited me out of the academy back when. Over the years, I had worked for him on and off, usually on Russian cases. He likes to remind me how green I was when he first spotted me. I talent-spotted you, man, he'd say, like he invented me. Used to make me nuts.

Growing up in Moscow like I did, I thought I was pretty streetwise. Moscow kids, we figured ourselves at the center of the universe, the center of a vast country that was always centralized. Moscow was the place where everything happened, politics, literature, science, movies, music, everything.

We thought we were hot shit. In fact, we were so cut off from the world, we didn't know how provincial we really were until word began to trickle through. Back then, all I had from outside, the only evidence there was better, something that reminded me of my dreams, was the music, Willie Conover's Jazz Hour on Voice of America, and a few illegal Beatles tapes.

Anyhow, when I met Lippert, I was new in New York, young, willing. Lippert saw he could use me. I spoke languages, I knew which fork to use, more or less, and Lippert told me he could use me on certain special jobs. I was plenty available for flattery, which Lippert doled out in just the right doses.

For years I didn't trust him. I knew he used me when it was convenient, but, retired or not, he was still the most connected guy I knew in the whole city.

The cop actors vied for Lippert's attention, asking him if they looked okay, if they walked okay, if they resembled the real thing. For a while, he passed out advice, and they sucked it up gratefully.

"You should get in on this consulting thing, man," said Sonny. "It's very competitive, I mean every ex-cop wants in, and some still on the job would love it, and I could help you get a gig if you want, you could be a movie cop, if you wanted, maybe even go on screen, like an extra or something, man. You're still pretty good-looking. I could introduce you." He glanced over at the fence that surrounded the studio, "Jesus, look at that," he added.

Beyond the fence was a group of Hassidic men, with long black curls and big black hats, white shirts, black pants. They had been kicking a soccer ball around. Now they came to the fence, and stared, incredulous, hostile, at the fake cops. Maybe they figured them for the real thing.

A black actor was sitting on a canvas chair, reading, his back against the chain-link fence. He heard somebody rattle the fence and looked up. A Hassidic guy said something disdainful about blacks. The actor got up, body tense. Other actors crowded around him.

Insults were exchanged. You could feel the anger rise. Everyone started yelling. Only the fence kept them from fighting.

It was as if the Crown Heights riots were starting all over.

"Just fucking cut it out," a crew member yelled. "Everybody, just back off," he said, and then it stopped. On our side it was only make-believe, and there was the chain-link fence.

"Can we talk, please?" I said to Sonny again. "And not about make-believe, okay? Now?"

"Don't get your hair in a braid, man," he said and walked me across the cement courtyard, away from the crowd.

We sat on a cement block and he asked what was eating me, what I'd been up to.

I told him what I knew about the dead woman – or maybe she was a girl – on the swing, and about Dina, the kid who found her.

"You went there how? How come?"

"I was taking some books to an old lady in Brooklyn, that part doesn't fucking matter, and I saw Dina running around in the street. I want you to tell me about duct tape, and about who does this kind of murder, does it ring any bells with you, anything you ever heard of? Sonny?"

"I heard about some, Albanian, maybe even Russkis, they get these girls, they prostitute them, the girls refuse, they try to run away, the creeps who own them do this kind of stuff. The duct tape, killing them this way, it's a warning, keep still, don't do anything, keep your mouth shut. It could be Mexicans, but I don't think so, not around here." He looked at his watch. "I can get out of here for an hour, if you want, I can take a look at the scene," he said. "You have your car? I'll follow you."

I didn't want Sonny at the scene, it wasn't my case, it would complicate things, but he was already on his way to the parking lot. I saw he was eager, glad somebody had asked him about the real world.

"Murder Inc.," were the first words out of Sonny Lippert's mouth when he climbed out of his dark green Jag near Fountain Avenue.

I walked him over to the playground where I'd seen the body. It had been taken away, but forensic crews were still picking over the site. Lippert followed my gaze.

"She was there," I said. "On the swing. Tied to it. Posed."

"Go on."

"Somebody was making a point," I said. "Right?"

"Anybody look good for it?"

"I don't know."

"Weird, man, this is exactly where the mob used to dump the bodies times I was a kid," said Sonny. "Murder Inc., Jesus Christ, it was famous, man, I mean we used to come over here and look for them. The bodies. You remember a song called 'When My Bobby Gets Home'? We kids used to sing 'When the Body Gets Cold'. All of us kids, all we wanted was to play ball for the Dodgers or join up with Murder Inc., maybe get to kill someone. Sometimes we did a cat, you know, strung it up from a light bulb, dumped the body out here. You don't think it's funny? Come on, Artie, man."

"Listen to me, Sonny, try to think."