Blood Will Out E-Book

21,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute Special Issue Book Series

- Sprache: Englisch

Unique in focus and international in scope, this book brings together 10 essays about the material, metaphorical, and symbolic importance of blood.

- An interdisciplinary study that unites the work of noted historians and anthropologists

- Incorporates insights from recent work in symbolism, kinship studies, medical anthropology, the anthropology of religion, the sociological study of finance, and textual analysis

- Covers topics such as Medieval European conceptions of blood; blood and the brain; blood and the cultural study of finance; and blood types, identity, and association in twentieth-century America

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 524

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Series page

Title page

Copyright page

Notes on contributors

Acknowledgements

Introduction: blood will out

The materiality of blood

Fungibility and substance

Donation

Religion-kinship-politics

The truth of blood

Vitality and flow; containment and stoppage; metaphor and naturalization

Conclusion: genes and vampires; multiple temporalities of blood

1 Lifeblood, liquidity, and cash transfusions: beyond metaphor in the cultural study of finance

Finance as blood sport: lifeblood, liquidity, bloodbaths, pressure, flow

Dissecting the physiology of capital circulation: The legacies of William Harvey

Organic economic analogies: Mixing more than metaphors

The bloody politics of financial intervention

Meta-materiality: Beyond metaphor in the study of finance

2 The way blood flows: the sacrificial value of intravenous drip use in Northeast Brazil

Water of life

Blood, sweat, broth, and Catholicism

Droughts and dryness, rain and tears

Soro vs broth: vein vs mouth

Blood substitutes and substitutional forms of sacrifice

Conclusion

3 Medieval European conceptions of blood: truth and human integrity

Blood reveals the truth

Blood fuses the body-soul unit

Blood defines the outlines of a person

The special status of Christ's and pious Christians' blood

The incoherent blood and bodies of women and Jews

Conclusions

4 The blood of Abraham: Mormon redemptive physicality and American idioms of kinship

A bloodless Communion?

The blood of Abraham

Conclusion: resurrected and unborn

5 Who is my stranger? Origins of the gift in wartime London, 1939-45

The blood bank and The gift

Knowing strangers

Knowing donors

Journeys of the gift

6 Bloodlines: blood types, identity, and association in twentieth-century America

7 ‘Searching for the truth’: tracing the moral properties of blood in Malaysian clinical pathology labs

Lab work

Biomedical spaces

Extracting blood

Samples, testing, and screening

The label as mediating artefact

Getting results; pursuing information

Qualities of blood

Conclusion

8 The art of bleeding: memory, martyrdom, and portraits in blood

Inside the Red Fort

Martyrs and memory

Coming together to bleed

Traces

Affective literalism

Sanguinary politics

Conclusion

9 Blood and the brain

The multiple meanings and symbolic resonance of blood: the missing blood

Ghostly blood

Finding the blood

Controlling the blood

Vessels of the blood

Facing blood in the brain

Concluding remarks

Index

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute Special Issue Book Series

The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute is the principal journal of the oldest anthropological organization in the world. It has attracted and inspired some of the world's greatest thinkers. International in scope, it presents accessible papers aimed at a broad anthropological readership. We are delighted to announce that their annual special issues are also repackaged and available to buy as books.

Volumes published so far:

This edition first published 2013

Originally published as Volume 19, Special Issue May 2013 of The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Society

© 2013 Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain & Ireland

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Janet Carsten to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Blood will out : essays on liquid transfers and flows / edited by Janet Carsten.

pages cm

“Originally published as volume 19, special Issue May 2013 of The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute”–

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-65628-0 (pbk.)

1. Blood–Symbolic aspects. 2. Blood–Social aspects. 3. Blood–History. I. Carsten, Janet, editor of compilation. II. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Special issue.

GT498.B55B578 2013

306.4–dc23

2013020970

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

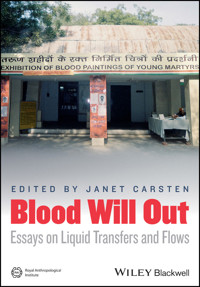

Cover image: Cover image: Outside exhibition of portraits painted in blood of Indian martyrs for Independence, held in Delhi in 2009 (photo Jacob Copeman).

Cover design by Richard Boxall Design Associates.

Notes on contributors

Bettina Bildhauer is a Reader in German at the University of St Andrews. She is the author of Medieval blood (University of Wales Press, 2006) and Filming the Middle Ages (Reaktion, 2011), and co-editor (with Robert Mills) of The monstrous Middle Ages (University of Wales Press, 2004) and (with Anke Bernau) Medieval film (Manchester University Press, 2009), as well as the author of several shorter pieces on medieval blood. Department of German, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, Fife, UK.

Fenella Cannell is Reader in Social Anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her books include Power and intimacy in the Christian Philippines (Cambridge University Press, 1999) and The Christianity of anthropology (Duke University Press, 2006). Her current research is with American Latter-day Saints. Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics, London, UK.

Janet Carsten is Professor of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of The heat of the hearth: kinship and community in a Malay fishing village (Clarendon Press, 1997) and After kinship (Cambridge University Press, 2004); and editor of Cultures of relatedness: new approaches to the study of kinship (Cambridge University Press, 2000) and Ghosts of memory: essays on remembrance and relatedness (Blackwell, 2007). Social Anthropology, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Jacob Copeman is a Lecturer in Social Anthropology at Edinburgh University. His publications include Veins of devotion: blood donation and religious experience in North India (Rutgers University Press, 2009/Routledge, 2012), Blood donation, bioeconomy, culture (ed., Sage, 2009) and The guru in South Asia: new interdisciplinary perspectives (co-ed. with Aya Ikegame, Routledge, 2012). Social Anthropology, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Susan E. Lederer is the Robert Turell Professor of the History of Medicine and Bioethics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Her books include Flesh and blood: organ transplantation and blood transfusion in twentieth-century America (Oxford University Press, 2008) and Subjected to science: human experimentation in America before the Second World War (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995). University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Emily Martin is Professor of Anthropology at New York University. She is the author of The woman in the body: a cultural analysis of reproduction (Beacon Press, 1982 [1987]), Flexible bodies: tracking immunity in American culture from the days of polio to the age of AIDS (Beacon Press, 1994), and Bipolar expeditions: mania and depression in American culture (Princeton University Press, 2007). Her current work is on the history and ethnography of experimental psychology. Department of Anthropology, New York University, New York, NY, USA.

Maya Mayblin gained her Ph.D. in 2005 from the London School of Economics and Political Science. She is the author of Gender, Catholicism, and morality in Brazil: virtuous husbands, powerful wives (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), and held a British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the University of Edinburgh, where she is Lecturer in Social Anthropology. Social Anthropology, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Kath Weston is Professor of Anthropology and Women, Gender, and Sexuality at the University of Virginia. Her publications include Families we choose (Second edition, Columbia University Press, 1997), Gender in real time (Routledge, 2002), Traveling light: on the road with America's poor (Beacon Press, 2008), and ‘Biosecuritization: the quest for synthetic blood and the taming of kinship’ (in Blood and kinship: matter for metaphor from ancient Rome to the present (eds) C.H. Johnson, B. Jussen, D.W. Sabean & S. Teuscher, Berghahn, 2013). Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Nicholas Whitfield completed his Ph.D. in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. He is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Social Studies of Medicine, McGill University. Department of Social Studies of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal QC, Canada.

Acknowledgements

The workshop for which this book was first written was held at the University of Edinburgh in May 2010, and funded by the Leverhulme Trust as part of a Leverhulme Major Research Fellowship. I am grateful to all the contributors for their many inspirations and comments, to the Leverhulme Trust for making this work possible, and to Jonathan Spencer for his support, his comments, and for suggesting the title. I also thank Richard Fardon and the anonymous readers for JRAI for their very helpful comments on an earlier draft of the introduction. Julie Hartley provided initial help collecting materials; I am grateful to her, and to Joanna Wiseman and Evangelos Chrysagis for their editorial assistance.

Introduction: blood will out

Janet Carsten

University of Edinburgh

Newspaper reports from Bangkok in March 2010 described a novel form of political demonstration. Thousands of demonstrators gathered to empty plastic containers of donated blood, collected from volunteers, on the fences and gateways to government headquarters. In a rite that seemed to combine elements of sacrifice and curse, and was also clearly a transformation of forms of civic participation in blood donation campaigns, the pouring away of blood became a vividly expressive act of political opposition to the perceived illegitimacy of the current regime (Associated Press 2010; see also Hugh-Jones 2011; Weston, this volume).

A little more than a year later, in April 2011, from a quite other part of the world, it was reported that, as prelude to Pope John Paul II's beatification, a phial of his blood would be displayed as an object of veneration by the Vatican: ‘The Vatican said the blood, which had been stored in a Rome hospital, had been kept in a liquid state by an anti-coagulant that was added when it was taken from him’ (Hooper 2011).

The entanglement of the medical and religious encapsulated by the papal phial was further underlined by the description of how this blood had been obtained, and its potential future destinations:

The Vatican said doctors had taken a quantity of blood from the pontiff while he lay dying, which had been sent in four containers to the blood transfusion centre at the Bambino Gesu hospital in Rome. Two ‘remained at the disposal’ of his private secretary, Stanislaw Dziwisz, who was later made a cardinal and the archbishop of Krakow (Hooper 2011).

What is blood? This volume begins from the premise that the meanings attributed to blood are neither self-evident nor stable across (or even within) different cultural and historical locations. The many meanings of blood that are captured in the essays that follow vividly attest to its polyvalent qualities and its unusual capacity for accruing layers of symbolic resonance. Whether literally present in spaces of blood donation, as in the twentieth-century London or US contexts discussed here by Nicholas Whitfield and by Susan Lederer, respectively, or indicated through elaborated metaphor, as in Kath Weston's discussion of the deployment of sanguinary metaphors in depictions of the economy, blood has the capacity to flow in many directions. Analysing the meanings of blood in particular contexts illuminates its special qualities as bodily substance, material, and metaphor. But, taken together, these essays also attempt to answer another kind of question: can we have a theory of blood, and what would such a theory look like? If blood, like money, seems to be more or less ubiquitous, it departs from money in lacking a well-worked seam of sociological or anthropological theory with which it is associated. This initial puzzle suggests that, in assembling a volume on blood, we need to attend both to implicit theories of blood and to the several dispersed fields where they might be located.

The significance of blood, as the two opening vignettes make clear, is not limited to any of anthropology's classic domains: politics, religion, kinship, or even to their more recent offshoots, such as the body or medical anthropology. Rather, the interest in blood lies in its propensity to travel within, between, and beyond all of these. Its scope, in other words, requires a broad view, and returns us to the insights of foundational work on symbolism, such as that of Claude Lévi-Strauss (1969a [1962]) or Victor Turner (1967). While the former drew attention to the fact that ‘some objects are good to think’, the latter attended closely to the links between material properties and their emotional resonance in specific contexts. In demonstrating blood's recurring but divergent significance across cultural and historical contexts, the essays collected here articulate another theme familiar from classic studies of symbolism: a tension between the ‘arbitrary’ nature of the sign (Saussure 1960 [1916]) and the particular power of ‘natural symbols’ (Douglas 2003 [1970]).1

But what kind of thing is blood? Is it an unusual bodily material, a sub-category of corporeal substance, or is it part of some larger category whose significance is not constrained by bodily features? Is it part of the person and relationships, or an object that can be commodified (Baud 2011)? Or does its uniqueness stem, as Stephen Hugh-Jones (2011) argues, from the many spheres in which it participates, and the corollary that it is irreducible to the category either of commodity or of personhood? The connections between the essays collected here suggest that the meanings of blood are paradoxically both under- and over-determined. Seemingly open to endless symbolic elaboration, its significance appears from one perspective to be curiously open; but from another point of view, it is this very excess of potentiality that is over-determined. Not only does blood have a remarkable range of meanings and associations in English (Carsten 2011), but many of these readily encompass their antinomies (Bynum 2007: 187). The essays in this volume demonstrate that blood may be associated with fungibility, or transformability, as well as essence; with truth and transcendence and also with lies and corruption; with contagion and violence but also with purity and harmony; and with vitality as well as death.

The contexts presented here are indeed wide-ranging: depictions of blood in German medieval religious and medical texts (Bildhauer); politically inspired portraiture executed literally in blood in contemporary India (Copeman); Mormon conceptions of blood in the United States (Cannell); transformations in ideas about blood donation in twentieth-century Britain and the United States (Whitfield; Lederer); practices concerned with the flow and fungibility of blood, food, and water in the body among peasants in Northeast Brazil (Mayblin); working practices in clinical pathology labs and blood banks in Malaysia (Carsten); the interpenetration of blood and finance in descriptions of trade and capitalism in the global economy (Weston); and up-to-date brain imaging for medical purposes in the United States in which blood seems strangely absent (Martin). In keeping with this diversity of contexts, the contributors approach their material in remarkably different ways. While several of the contributions are historically framed, relying on both documentary and visual material, others attend to contemporary narratives about blood, and are based on close observation of particular contexts or the interplay between spoken exegesis and visual images. Some of the discussions rely on a juxtaposition of such different kinds of evidence. We hope that the range of evidence and approaches offered within and between these essays will be an added enticement for readers to engage with our subject matter.

The obvious geographical, cultural, and historical discontinuities between the sites discussed here suggest that commonalities between them might be fortuitous or far-fetched. In fact, the essays demonstrate continuities in blood symbolism where we might not expect them – in the idea that blood reveals the truth, for example, which appears in the context of medieval medical and religious texts discussed by Bettina Bildhauer, in the exegesis on portraits painted in blood of Indian martyrs for Independence analysed by Jacob Copeman, in the history of twentieth-century blood-typing documented by Lederer, and in the Malaysian political rhetoric and practices of clinical pathology labs that I describe. But there are also discontinuities in contexts where we might perhaps expect to see similarities. For example, the two historical considerations of the twentieth-century development of blood donation and transfusion services considered here, that of Britain, discussed by Whitfield, and of the United States, by Lederer, reveal some very different underlying social anxieties – in the one case about class, and in the other about race, among other concerns.2 To take another example, the two contemporary Christian settings – that of Latter-day Saints in the United States considered by Fenella Cannell, and rural Catholics in Northeast Brazil by Maya Mayblin – reveal strikingly divergent ideas about blood. The rather ‘eviscerated’ notions of blood articulated in the Mormon case may be linked to wider Protestant precepts and iconography, while Mayblin's analysis shows a remarkable ‘fit’ between the ideas about blood, water, and sacrifice that she elucidates and prevailing conditions of water scarcity in the local ecology. The contrast thus appears to speak to a complex interplay between historical forces and the development of Christianity in specific locations. But it also is suggestive of how symbolic registers may be elaborated (or reduced) in an implicitly contrastive logic that underlies and contributes to the historical differentiation of divergent branches of a world religion.

If discontinuities between the cases discussed here emerge as much as continuities, this might perhaps be regarded as an expected outcome of the close attention paid by the authors of these essays to the specific sites, locations, historical eras, and cultures they have studied. In this sense, the essays are separately and collectively intended as a contribution to an ‘anthropology of blood’. In drawing together the themes that unite them in this introduction, however, I have endeavoured to foreground continuities where these emerge – perhaps partly because these seem more arresting in the face of the obvious dissimilarities between contexts. This disposition also reflects the starting-point for this collective endeavour, which was not only to grasp the cultural specificities of ideas about blood, but also to look for commonalities, and to understand their wider significance. Locating this discussion in a wider anthropological literature has also highlighted how, while there is much previous work that is relevant, there has been surprisingly little sustained attention given to placing this topic in a comparative frame.

In tracing the ways in which blood flows within and beyond the locations discussed in this collection, what emerges most clearly is the literal uncontainability of blood – its capacity to move between domains, including the religious, political, familial, financial, artistic, and medical, which in other contexts are often kept separate. Delineating the contours of this uncontainability of blood, and examining how it operates, brings to light further themes that illuminate blood's particular qualities. Some are closely tied to its material attributes and its bodily manifestations, others involve symbolic or metaphoric elaboration, but often the distinctions between physical stuff and metaphorical allusion seem porous and difficult to disentangle. Some symbolic associations may refer to or resonate with others, and may also allude to physical or material qualities. A distinction between literal or material qualities and metaphorical ones is of course further undermined by the fact that, as the essays collected here show, what are claimed as the literal or material qualities of blood are themselves culturally and historically variable.3 Tim Ingold's emphasis on the processual and relational properties of materials seems apt here: ‘To describe the properties of materials is to tell the stories of what happens to them as they flow, mix and mutate’ (2011: 30).

In the discussion that follows, the themes of materiality, bodily connection, contagion, violence, transformability, and vitality are associated with apparently literal or physical attributes of blood. But they may also emerge in more symbolic or metaphorical ways. So, as in the example of the Thai political demonstrations or Pope John Paul II's blood with which I began, these themes segue into others that are less closely tied to blood's physical manifestations: ancestral connection, truth, morality, corruption, and transcendence. And this suggests that blood might be a productive medium through which to consider symbolic processes, metaphor, and naturalization (see Jackson 1983; Lakoff & Johnson 1980).

The main themes of the essays have already been mentioned: blood's multiple and sometimes contradictory registers; the relation between metaphor and materiality; blood's apparent capacity to encapsulate the truth; its association with vitality. All of the essays in different ways bring together practices or discourses that might more conventionally be analysed separately, including those concerning religion, medicine, politics, kinship, and economics, showing how images of blood or ideas and practices relating to blood run through these, sometimes providing continuities, but also often disjunctures, of register.

In keeping with blood's tendency to flow between and beyond specific sites, the structure of this introduction does not adhere to the bounded domains of classic anthropological texts. Through the medium of blood, we see how – as in real life – politics may merge with religion or medicine, and the lines between morality, kinship, religious ritual, and health practices may be difficult to discern. This necessitates paying close attention through these themes to the ways in which metaphors are deployed, as well as to blood's physical attributes, before tacking back to our starting-point. To explore what blood is, what a theory of it might look like, or the wider processes such a theory might illuminate, we need first to delineate some of blood's distinctive features.

The materiality of blood

Anthropological analysis does not always proceed from what is hidden or obscure. Sometimes it is the most obvious features of objects or relations that call for attention. Blood has a unique combination of material properties that make it distinctive within and outside the body. Colour and liquidity are the most striking of these, but their co-occurrence and association in the body with heat, and the propensity of blood to clot, turning from liquid to solid, may be equally important to its capacity for symbolic elaboration (see Carsten 2011; Fraser & Valentine 2006). Colour was of course central to Victor Turner's classic symbolic analysis, and his discussion underlines the significance of the connection between the striking visual features of blood and its emotional resonance (1967: 88-9).

Several of the authors in this volume connect blood's material properties to the way it is symbolically elaborated in particular contexts. Bildhauer's discussion of medieval texts, building on her earlier study (Bildhauer 2006), shows how both colour and heat together are central to its medical and miraculous properties. Here we are immediately confronted with the impossibility of separating these qualities from religious notions. Medieval concepts of blood, as Caroline Bynum (2007) has shown, are bound up with ideas about the sacred and, in particular, with the miraculous eternal vitality of Christ's blood, encapsulated in powerful relics. While Christ's blood in these ideas is seen as exceptional, the blood of humans, as discussed below, holds the body and soul together. Normally hidden in the body, when it becomes visible it gives access to the truth. Because of its living qualities, bleeding is a sign of crisis. Good blood is a sign of health, while either too much or too little blood in the body may cause sickness and require regulation through medical attention. Blood can thus secure life, but also be a source of danger through its lack of boundaries.

In an utterly different context – but one that is linked by the importance of Catholicism – Mayblin considers the significance of blood for peasants in the drought-ridden Northeast of Brazil. She shows how blood partakes in a ‘fluid economy’ where its liquid property is part of a wider system of ideas in which access to water for agriculture is paramount to survival, but which also connects to religious ideas about the significance of Christ's sacrifice. Here peasants understand themselves to be involved in their own sacrificial labour in the fields in which the water and nourishment they lose through the sweat and energy of hard work must be continually replenished. Crucially, water and food that are consumed are transformed in the body into blood. But when these villagers are unwell, their preferred form of cure is to administer sterile isotonic solution, soro, intravenously as a form of instant infusion that replenishes and strengthens the body. This especially pure form of liquid can be likened to the sacrificial water that gushes from Christ's side, as depicted in highly valued local religious imagery, and which is associated with the holy spirit and with life. Soro is understood to be particularly effective in replenishing blood that is continually depleted through everyday human sacrificial labour. Here water, food, and blood exist as transformations, or possible substitutions, of each other, and exhibit varying states of purity – a theme that is also present in Bildhauer's discussion of medieval texts, and to which I return below.

While material properties of blood are clearly central to both Bildhauer and Mayblin's analyses, they are also just one starting-point for grasping the medical and religious understandings delineated in their essays. In analogous ways, the colour and liquidity of blood might be seen to enable other practices discussed in this volume. The portraits of Indian martyrs for Independence described by Copeman that are literally (as well as metaphorically) painted in blood make use of its redness and liquid form – though interestingly, as neither quality persists outside the body, these have to be artificially enhanced. Here the interpenetration of metaphorical and literal meanings of blood is especially dense, and the emotional resonance of these pictures rests on the complex entanglement of historical, national, political, medical, and bodily perceptions of sacrifice (see also Copeman 2009a). If Copeman's essay offers a particularly vivid depiction of how different meanings of blood evoke and amplify each other, it also powerfully demonstrates the centrality of visual and material cues to these wider resonances.

But of course blood's physical properties cannot simply be thought of as the causal factor in what is obviously a very complex web of signification. Sometimes these properties actually limit the uses to which blood may be put. Thus in the twentieth-century development of blood collection for transfusion and of blood-typing, discussed by Lederer and by Whitfield for the United States and Britain, respectively, physiological barriers to the use of one person's blood in the body of another had to be overcome. Nevertheless, as both these essays demonstrate, the fact that transfusion might result in adverse bodily reaction was itself amenable to interpretation in social and racial terms. The history of premodern European ideas about the links between blood and heredity shows how elements in such thinking long pre-dated innovations in blood collection (de Miramon 2009; Nirenberg 2009). Such entanglements were both persistent and amenable to historical transformation in new circumstances (see, e.g., Foucault 1990 [1976]: 147).

Accounts of one of the earliest experiments in animal-to-human blood transfusion, conducted in 1667 under the auspices of the Royal Society, in which Arthur Coga was transfused with the blood of a sheep, indicate that the religious and moral connotations of blood were very apparent to participants. Coga's assertion (made in Latin) that ‘sheep's blood has some symbolic power, like the blood of Christ, for Christ is the lamb of God’, reportedly ‘became a topic of London wit’ (Schaffer 1998: 101). While the leap from scientific experiments on transfusion to Lamb of God was taken humourously, concerns about the moral and spiritual qualities of blood permeate contemporary discussions about such experiments (see Schaffer 1998). It appears likely that, as Mayblin suggests, the liquidity of blood encourages a heightened possibility of multiple associations envisioned in terms of flow within and between bodies. But the entanglements of scientific rationalism and religious imagery also underline that the material qualities of blood are only one plausible starting-point for understanding its symbolic salience.

Fungibility and substance

We are already confronted by the difficulty of containing an anthropological discussion of blood within any of its particular dimensions. Attention to its material qualities has merged with consideration of religious, political, racial, and other matters. But there is an interesting symmetry here in terms of understandings of blood within the body. The essays of Bildhauer and Mayblin underline how blood may be conceived as the transformation in the body of food that has been consumed. These are just two instances of a culturally more widespread phenomenon, partly associated with the spread of humoral medicine, and which can also encompass other bodily fluids, such as semen and breast milk, that are understood as transformations of blood (see, e.g., Carsten 1997; Good & delVechio Good 1992). Thus blood itself is not a stable entity, and its composition and quantity may be altered through adjustments to diet, blood-letting, or other means that are undertaken to achieve improvements to health and/or the proper balance of different humours.

Changes in the composition or quantity of blood in the body may be purposefully achieved but they may also be inadvertent, resulting from illness, accident, or misadventure or – as in the case of peasants in Northeast Brazil – from the sheer wear and tear of hard work. But one might say that processes of life itself and social exchange bring about such alterations. The consumption of food, breastfeeding, and sex are widely understood to have serious implications for health and well-being. Elaborate rules governing these practices in order to maintain purity or reduce the possibility of contagion, such as those of the caste system in India, are one expression of such ideas (see, e.g., Daniel 1984; Lambert 2000; Marriott 1976; Marriott & Inden 1977). The physical importance of blood within the body, and its role in supporting life, make it an apparently obvious focus for regimes of bodily vigilance through blood-letting or other means. One might see the widespread occurrence of menstrual taboos or the negative associations of menstruation as more or less over-determined both by the significance of blood and by the connection of menstruation with processes of fertility, sex, and gender (Knight 1991; Martin 1992 [1987]; this volume).

As well as being subject to transformation within the body, blood can of course also be thought to be a vector of connection between bodies or persons. This may be articulated as occurring through the transfer of semen or breast milk (both, as noted, perceived as transformed blood), through maternal feeding in the womb, or through habitual acts of commensality, which are perceived to produce blood of the same kind in the different bodies of those who share food. Here liquidity seems to be a key quality, and the symbolic resonance of bodily fluids may be enhanced by the fact that sexual intercourse, breastfeeding, and family meals are often occasions of heightened emotionality (Taylor 1992; Turner 1967). As historians and anthropologists have observed, the physical transformation understood in Christian ideas to be set in train by marital relations – in which husband and wife become ‘one body’ or ‘one flesh’ – had profound implications for ideas about marriage and marriageability in Europe (Johnson, Jussen, Sabean & Teuscher 2013; Kuper 2009). A parallel can be drawn here with a concern in Islamic contexts about the potential incestuous implications of breastfeeding in case of future marriage between those who have consumed milk from the same woman (Carsten 1995; Parkes 2004; 2005).

In many cultures, being ‘of one blood’ or the phrase ‘blood relation’ connotes kinship. While this connection might seem almost too obvious to be worth stating, and is certainly central to Euro-American ideas about relatedness (Schneider 1980 [1968]), anthropological renditions of exactly how the connection between blood and kinship is understood further afield have often been surprisingly imprecise or under-specified (Carsten 2011; Ingold 2007: 110-11).4 And this seems to be partly a result of the implicit conflation of Euro-American indigenous ideas with anthropological analysis of the sort that David Schneider (1984) warned against. Somewhat bizarrely, however, considering the attention Schneider paid to sexual procreation in this regard, his own usage (and that of his informants) of blood and the ‘blood relation’ in American kinship was highly unspecified (Carsten 2004: 112), and this is the starting-point for Cannell's essay in this volume. As she elegantly documents, blood in US culture – or in the subculture that Mormonism represents – can have many meanings, and these cannot be assumed to be historically or culturally stable.

If materiality constitutes the first set of under-theorized aspects of blood to be considered here, then kinship can be seen as a second field in which blood is often invoked but more rarely analysed with much theoretical precision. Because of the continuities between kinship and wider ideas of social connection, this is a significant lapse that inhibits understanding of the ways in which rather abstract political ideologies that draw on kinship, such as nationalism, are rendered emotionally salient (Anderson 1991 [1983]; Carsten 2004: chap 6; Foucault 1990 [1976]; Robertson 2002; 2012). Before returning to the power of blood as political and religious symbol, I take up another apparently more physically circumscribed theme from the contributions in this volume – the importance of blood in medical contexts.

Donation

We have seen how the imagery of blood in kinship connection may blend ideas that have a literal referent, in terms of bodily fluids, with more symbolic or metaphorical usages. But metaphorical allusions to connections ‘in the blood’ apparently also occur in the absence of any obvious literal source. The donation and collection of blood for transfusion might then be expected to provide a rich and rather open set of opportunities for possible symbolic elaboration. Not surprisingly, anthropologists have recently turned to blood donation to explore its meanings and cultural significance (see Copeman 2009b). An emerging body of scholarship on blood donation in New Guinea (Street 2009), India (Copeman 2004; 2005; 2008; 2009a; 2009c), Brazil (Sanabria 2009), Sri Lanka (Simpson 2009), the United Kingdom (H. Busby 2006), and the Indian community in Houston, USA (Reddy 2007), amongst other locations, demonstrates the complex ways in which blood donation both draws on and expands local practices and idioms of gift-giving, the body, political, religious, or personal sacrifice, kinship connection, and ethics. One obvious point underlined by this work is the importance of considering blood donation not as an isolated phenomenon, but as a ‘total social fact’ – to co-opt an apt Maussian phrase.

Efforts to encourage blood donation in contexts of scarcity, as well as the declared motivations of donors, draw on ethical discourses from a combination of religion, politics, or kinship – as conventionally delineated by anthropologists. This suggests that an analysis of the symbolic mechanisms through which blood operates needs to place the medical contexts in which blood donation occurs within this much wider frame, and, conversely, that medical practices have the effect of multiplying the emotional and symbolic potential of blood (Copeman 2009a; 2009b; Hugh-Jones 2011). There is a parallel to be drawn here with organ donation, in which a shortage of available organs has been seen to jeopardize potentially the ethical management of transplantation. While attention has been focused on ‘tissue economies’ (Waldby & Mitchell 2006), issues of ‘bioavailability’ (Cohen 2005), or the trafficking of human organs (Scheper-Hughes 2000; 2004), it is also clear that such pressures are often ambivalently experienced, for example, through the medium of family ties (Das 2010; Fox & Swazey 1992; 2002 [1974]; Lock 2000; 2002; Sharp 1995; Simmons, Simmons & Marine 1987). Perhaps not surprisingly, the connections to donors and their families envisaged by organ recipients also have the potential to be elaborated in terms of kinship, and to be understood as transforming aspects of the person. This is particularly evident in cases of heart transplants, and is apparently associated with the heart's centrality to notions of the person and understandings of it as the seat of the emotions (Bound Alberti 2010; Lock 2002; Sharp 2006).

Blood donation seems generally to be apprehended in terms of more diffuse relations than those set in train by heart transplantation. Nevertheless, Copeman notes the strong link between the idea that donated blood has come ‘from the heart’ and the authenticity of the emotions flowing with donation. This is part of the efficacy of the blood portraits he describes. Blood donors I spoke to in both Malaysia and the United Kingdom often situated their acts of donation within a sequence of kinship experiences involving histories of family illness or parental acts of blood donation (see also Waldby 2002). And in Malaysia I was told of patients who spoke of the ways their bodies had been altered following blood transfusion in line with what they assumed had been the personal or ethnic characteristics of the source of the blood they had received.

Far from bracketing off these kinds of associations, in the conditions of scarcity that pertain to the availability of blood for medical uses, publicity for blood campaigns actually relies on the emotional resonance of family ties, ill-health, and often also of national sacrifice (Copeman 2009a; Simpson 2004; 2009). Historical accounts of the establishment of blood collection and transfusion services are of particular interest in showing the articulation of medical, political, familial, and other understandings of blood as they are reformulated for new purposes. The essays of Lederer and Whitfield in this volume speak to the complexity of these manoeuvres. The expansion, rationalization, and bureaucratization of blood banking in London during the Second World War together with new technologies of pooling and fractionating blood, described by Whitfield, necessarily distanced blood donors from recipients. This was accompanied, somewhat paradoxically, by a need to make potential recipients more vividly present to donors in order to maintain adequate supplies. New forms of propaganda featuring fictionalized stories about recipients were devised to meet this need. But how much specificity or distance was the right amount? While ideas of kinship and locality were deployed to maintain a sense of connection to recipients, Whitfield also shows how ‘strategic anonymity’ was a means to mitigate a shift from a system in which the danger of too much closeness between donor and recipient was recognized, to one where too great a distance posed a different kind of threat.5

During this period, in which existing class relations were perceived to be undergoing a thorough upheaval as a result of war conditions (as at least the British myth of this era would have it), it would seem that class distinctions between donors and recipients were downplayed. The stories used in publicity for blood donation are at once personalized and generic – they concern ‘ordinary men and women’, soldiers, sisters, and mothers – with features or faces made unspecific by the style of illustration. Here Jonathan Parry's acute observations about the gift (1986) – where it is only under the conditions of capitalism that there is a need to establish the fetishized category of the ‘pure’, disinterested gift – seem particularly apposite. Rhetorical allusions to a community bound by the gift of sacrifice for the nation express how the category of pure gift can be instantiated in blood donation. Richard Titmuss's emphasis on ‘the gift relationship’ (1997 [1970]) was thus, as Whitfield shows, an accurate reflection of a response to technological changes that had occurred some decades before his study.

In the US case discussed by Lederer, the development of blood-typing in the early to mid-twentieth century is interwoven with ideas about race together with religion and the Cold War. The scientific analysis of blood has the capacity to reveal the truth – as does blood in other cases discussed in this volume (see below). But what kind of truths are these? Here anxieties about the specificity of blood are accurately mapped onto social anxieties about racial mixing (see also Lederer 2008; Weston 2001), while class – a focus of British anxieties – remains a more submerged feature. Religion, as Lederer shows in this volume, may blend with or be separated from racial categories. Perhaps not surprisingly, her examples include discourses about the distinctiveness of Jewish blood, which was of course a theme in medieval and early modern European texts (Bildhauer 2006; this volume; Bynum 2007; Nirenberg 2009). But she also documents the active avoidance of interracial blood transfusion, an avoidance which apparently persisted in Mormon hospitals, even after the abandonment by the 1970s of separate blood supplies for white and black patients (Lederer 2008: 197).6

Lederer's exposition of the development of blood-typing and its capacity to blend with earlier associations of blood can be supplemented by more recent cases of anxiety about contagion, and scandals involving contaminated blood in China, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere associated with the HIV/AIDS pandemic (Anagnost 2006; Baud 2011; Chaveau 2011; Feldman & Bayer 1999; Laqueur 1999; Shao 2006; Shao & Scoggin 2009; Starr 1998). Thus while the donation of blood has the power to evoke community and kinship, and this may be reinforced by medical usages and scientific typologies, its ‘symbolic overload’ has clearly not been curtailed by scientific specification. The donation of blood is, for many who are not permitted to donate, an exclusionary rather than an inclusive act (Copeman 2009a; Seeman 1999; Strong 2009; Valentine 2005). The trope of ‘bad blood’, a ‘euphemism’ for syphilis in the United States, carries associations that merge race, ancestry, and sexual practice (Lederer 2008: 115-16, 148). And it is precisely because of the multiple connotations of blood, and the histories of these exclusions, that being refused permission to donate is as suffused with resonance as is the act of donation.

Religion-kinship-politics

Blood donation, as we have seen, has political, religious, economic, and familial significance. Each of the themes discussed here has segued into others; blood's capacity to flow in different directions renders its analysis peculiarly difficult to contain within any specified topic. The subheading ‘religion-kinship-politics’ is intended to gesture to this tendency, but also to serve as a reminder that these distinct domains are analytical artefacts as well as ideological features of modernity (see Cannell & McKinnon 2013; Yanagisako & Delaney 1995). While this ideology may predispose us to see the compartmentalization of realms of life, such as the clinical pathology labs described in my essay, or forms of Christian worship evoked by Cannell and by Mayblin, as obvious or self-evident, attending to the manner in which blood flows within and between such domains highlights their artefactual nature. My essay shows how, as the blood sample travels around the clearly delimited space of the lab, it accrues and sheds different kinds of attributes which enfold moral, ethical, and kinship ascriptions that hold within and beyond the lab's boundaries. Although these boundaries are actively guarded and maintained, they are, inevitably, also porous. ‘Blood flows’ thus illuminate not only blood itself, but also the work that domaining does – and the limits of domaining.

In this section and those that follow, I turn from the more physical attributes of blood to its looser, symbolic associations. A central paradox here concerns stability. Understandings of blood in the body, explored here by Bildhauer, Mayblin, and others, often emphasize its fungibility and its transformative potential. And Christ's blood is in Christianity attributed with transformative powers to a miraculous degree (Bildhauer, this volume; Bynum 2007). The ritual of Holy Communion, or Eucharist, for many Christians, involves a literal transubstantiation of communion wine into the blood of Christ (Feeley-Harnik 1981; Mayblin, this volume). The phial of Pope John Paul II's blood referred to at the beginning of this introduction clearly partakes of a long history of miraculous and transforming blood. But blood in Euro-American ideas of ancestry and descent is also generally understood to stand for permanence and fixity (Schneider 1980 [1968]). Weston (1995: 103) has commented on this tension in the meanings attributed to ‘biological connection’ and ‘blood ties’ in notions of kinship in the United States and Europe – where, in spite of its obvious association with the changing processes of life, biology is taken to stand for permanence. Blood may also be a potent symbol of disconnection and erasure in ideologies of kinship and ideas about family connection. Thus studies of adoption in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere show the importance of idioms of blood in articulating these disconnections, and also their permanent consequences (see Carsten 2000; Kim 2010).

In Cannell's contribution to this volume, different US Mormon understandings of blood are carefully teased apart. Significantly, the Mormon version of the ritual of Communion with which Cannell opens her essay involves a severely pared down reference to the Communion wine and its transformative potential. Here the symbolism of wine and blood is indicated by paper cups of water, and this can be associated with the Mormon proscription of alcohol as well as a wider history of Puritan practices and beliefs. But it also reflects an emphasis on the resurrected body of Christ, Cannell argues, and on redemption rather than the suffering body. One might say that Christ's blood has, like the Communion wine, been ‘bleached’ in the visual conventions of Mormon aesthetics – where the dazzling whiteness of favoured statues of Christ makes a stark contrast with, for example, the visceral prominence of red blood in the medieval images discussed in Bildhauer's essay (see also Bynum 2007) or Spanish seventeenth-century religious statuary (Bray 2009).

An emphasis on whiteness, light, and simplicity does not, however, inhibit a remarkable proliferation of Mormon ideas about blood. Here the blood of ancestry is highly elaborated: the injunction to trace family genealogy coexists with the revelation to teenagers of their biblical ascription to one of the twelve tribes of Israel in a ritual of Patriarchal Blessing. These two modes of ancestry reflect the joint importance of choice and destiny that is characteristic of Mormon eschatology. The reflections of Cannell's informants on possible interpretations of a particular ancestral ascription highlight the potentially troubling inferences of race and the ideas of permanence with which inheritance is invested. Here one senses that ideas about biblical descent are potentially in conflict with their personal and ethical implications for contemporary adherents. For some, there is unease about the connotations of these ideas – the manner in which personal agency, which is also a central Mormon tenet, may be constrained by the permanence of ancestry and ideas about race. Cannell suggests both that ideas about race are today less exclusionary than they were in the past (in line with more mainstream US ideology), and that the ambiguities surrounding blood, inheritance, and individual agency reinforce for adherents the mystery and sacredness of kinship that is central to Mormon beliefs.

Although Cannell's informants did not speak about these matters, it is significant that, as noted above, Mormon hospitals in the United States have a history of exclusionary practices of blood transfusion in which Mormons were reluctant to take African American blood (Lederer 2008: 197; this volume). This vivid exemplification of the manner in which literal and symbolic aspects of blood may flow into each other is also evident in Copeman's essay. As we have seen, the starting-point for Copeman's central protagonists seems uncompromisingly literal: portraits of Indian martyrs to Independence are painted in blood in order to evoke a strong emotional response in those who view them. Here, in a seemingly similar set of strategies to those of the Thai demonstrators described in my opening vignette, blood must be physically present to induce a reaction. But as Copeman shows, literalness also has a kind of evanescent quality: blood's colour fades; it is not necessarily clear how central the medium is to the message that viewers of these portraits perceive. In any case, blood's presence in both these cases is intended to invoke further layers of symbolic association – to the blood of martyrdom and sacrifice (see Castelli 2011; Copeman 2009a). It also serves as a reminder, or a threat, of further acts of violence and sacrifice that may be demanded in the name of the nation in the future. Here not only have religious, medical, corporeal, and political messages converged through the medium of blood, but temporal dimensions of what blood invokes in the past, present, and future have been merged so that the past is made viscerally present. Blood's literal presence is required, it seems, in order to make evident that its materiality is superseded by a plethora of higher symbolic meanings.

The truth of blood

What kind of stuff is blood? One answer given by the essays in this collection, perhaps unexpectedly, is that it is the stuff of truth. The capacity of blood to ‘reveal the truth’ – morally, personally, politically, and medically – is a striking theme uniting many of the contexts considered here. This emerges very clearly in Bildhauer's discussion of medieval texts, where blood that becomes visible has a unique capacity to reveal the inner state of the person, his or her moral purity or corruption, as well as his or her health. These ideas would seem to draw partly on biblical notions as well as on humoral medicine. Blood in Leviticus (17: 1-15) is described, as in the texts considered by Bildhauer, as both the animating life-force and the bearer of the soul. For this reason its consumption is proscribed in Leviticus.7 But we have also seen that blood's truth-bearing capacities are reflected in the twentieth-century scientific development of blood-typing in the United States considered by Lederer. Here it is particular kinds of scientific, racial, personal, and moral truth that are revealed. In a parallel case, Jennifer Robertson (2002; 2012) has shown how the elaboration of discourses around blood-typing in Japan encompasses ideas about horoscopes, personality, blood donation, match-making, eugenics, and the nation. The possibility of finding true love through matching blood types, for example, or the importance of eating correctly for one's blood type, shows how the nature of these truths is continually under revision depending on the social and political context as well as the state of scientific discoveries.

In the context of clinical pathology labs and blood banks in Malaysia, discussed in my essay, the truths that blood is required to establish might be assumed to be straightforwardly medical. These are sites of diagnostic testing in which the blood sample is the most common medium for analysis. But here we see how, as bodily samples travel around the lab, they may be attributed meanings by the staff that conflate medical, personal, familial, and moral qualities. Samples and their accompanying documentation are thus liable to accrue layers of significance that might be thought quite outside the processes and purposes of laboratory analysis. Meanwhile, in the radically different context of Malaysian public politics, the heavily contested blood sample of the de facto leader of the opposition, Anwar Ibrahim, arrested in 2008 under a charge of sodomy, was claimed by the government as an icon of truth, and apparently required in order to reveal his moral state. But to an increasingly incredulous Malaysian public, it seemed that this blatantly political manoeuvre might backfire – to reveal instead political corruption in high places. In this somewhat bizarre conjunction of routine laboratory testing and theatrical politics, the truths that blood may reveal are far from stable; they have the capacity to uncover further truths, and also to destabilize moral and political certainties.

The truth-bearing quality of blood appears, then, to give it special efficacy, as is evident in Copeman's case of Indian blood portraits. Donating blood for the purpose of retouching these paintings, like other acts of donation, attests to the truth of the donor's commitment. But here the ‘symbolic overload’ of blood, its capacity to be read in so many ways, suggests that any one truth already implies all the other truths that may be embodied in blood. And this may connect to the way in which blood seems in many contexts to be perceived as a kind of essence – of the person, and of his or her bodily and spiritual health, disease, or corruption – as is clear, for example, in the cases discussed by Bildhauer and by Mayblin.

But there is a caveat here because we should beware of essentializing blood, or of an overly reductive approach to the different cultural and historical locations considered in this volume. As Fenella Cannell and Emily Martin show in their essays, blood may be many things even within one closely connected set of contexts. Martin's arresting example of contemporary medical images in which the brain appears without blood reminds us that, even within a quite narrow frame of medical understandings, blood has many meanings. If the blood-brain barrier discussed in her essay is physiologically important in limiting the uptake of pharmaceuticals by the brain, it can also be contrasted with images of a brain suffused with blood, and in which leakages or embolisms are a potential cause of death. While the brain can be visualized as devoid of blood but with millions of neurones firing to light up fMRI scans, Martin suggests that the cerebro-spinal fluid can also be seen as a purer form of blood, dealing with the higher cognitive functions of thought and control associated with the brain. And placing this understanding of the cerebro-spinal fluid alongside Martin's earlier insights about gender and medical representations of the body in The woman in the body (1992 [1987]), as she does here, provides a revealing contrast. Whereas menstrual blood and menopause were shown in that work to be associated with chaos, waste, pollution, and decay, and of course with women, blood's function here is one of nourishing the brain, and essentially maternal. But cerebro-spinal fluid is imagined as a highly refined and more male form of blood. Martin shows how this hierarchical differentiation of blood in the body is linked to purity and to gender imagery in a way that reveals striking parallels with the cases discussed by Bildhauer and by Mayblin. But she also makes clear that understandings of blood remain open to new truths of scientific discovery – for example, the prioritization of cognition – while still retaining their salience.

Vitality and flow; containment and stoppage; metaphor and naturalization

I suggested above that blood's apparently unique capacity among bodily substances to reveal the truth could be linked to its strong association with life itself. The idea that blood embodies the life-force is evident in the proscriptions of Leviticus, in Bildhauer's consideration of medieval texts, and in the practices of the Brazilian peasants considered by Mayblin, but it also occurs outside Judaeo-Christian contexts. Conducting village fieldwork in Malaysia in the 1980s, I was told that, at the time of death, ‘the soul leaves the body and all the blood flows out’ – even if this was not visible to the human eye. If a person died in the house, everything in the house, especially the food, became soaked with blood. Therefore food could not be cooked or consumed in a house where a death had occurred until after the funeral had taken place (Carsten 1997: 124).

Vitality in these ideas is apparently linked to the flow and liquidity of blood – to its mobility. Excessive bleeding is one obvious cause and sign of death – in this sense blood's truth-bearing capacity is incontrovertible. Images of both containment and of permeability occur in several of the contributions here. Outpourings of blood – whether induced through purposeful acts of violence or incurred by accident – are signs of danger. And, as Martin notes, stoppages of blood, clots and embolisms, are equally hazardous. But the flow of blood – or life – may also be perceived as religious sacrifice – as in practices discussed by Bildhauer and by Mayblin. In Christian contexts, such pouring out of blood may be linked to Christ's sacrifice for humanity, and the flow of blood can be a means to achieve transcendence (see Bynum 2007). Transcendence may also be sought through political acts of violence such as those considered by Copeman, or more explicit acts of martyrdom (Castelli 2011) that are also invoked in the idiom of sacrifice. The antinomies which blood encompasses here – involving life and death, movement and stoppage, health and disease, violence and peace, the sacred and the profane – make clear how its polyvalent associations extend in an extraordinary multiplicity of directions.

But even this plethora of resonances does not exhaust the symbolic idioms in which blood participates. Whereas Martin's essay, which closes this volume, draws attention to the spaces where blood does not flow, and to stoppages and blockages, Weston's opening contribution is concerned with the flow of lifeblood in the financial body. Her essay lays out with wonderful precision the layered resonances of different somatic models and understandings of blood to which contemporary descriptions of the economy refer. Images of ‘lifeblood’, ‘circulation’, ‘flow’, ‘liquidity’, or ‘haemorrhaging’ in the financial system resonate with understandings of blood in the body. While the circulatory model discovered by William Harvey in the early seventeenth century is predominant here, Weston shows how older notions that predate Harvey's model may also be called upon, involving, for example, ideas about stagnation of the economy and the blood-letting that is necessary to deal with it. As well as demonstrating the pervasiveness of sanguinary images in depictions of the financial system, and laying out an archaeology of somatic models, Weston's essay confronts the central problem of this volume: the issue of metaphor.

How should we understand the widespread occurrence of metaphors of blood, and what is their significance? Together with other contributors in this volume, Weston places the term ‘resonance’ alongside metaphor, but she also includes other figures of speech and literary device in her analysis, such as analogy, allegory, and synecdoche. The multiple resonances of blood, she suggests, which are evident in all the cases described here, enable a kind of ricochet effect, in which resonances referred to through linguistic means pile in on each other, but without requiring the primacy of one particular set of references or idioms to be specified or even suggested. Thus in the case she describes, the ‘naturalness’ of the organic analogy in finance is so deeply and historically embedded in patterns of language as to pass without question, and indeed one effect is to obscure the fragilities, instabilities, and inequalities of the financial system itself.8 While one might object that this implies a Whorfian model of the world in which language determines thought and action, this conclusion is actually too simplistic. The significance of the bodily processes that are engaged here, the very materiality of blood, implies that there is no crude way in which one could ascribe primacy in these processes either to the physicality of blood or to linguistic devices. Rather, the power of metaphors and images of blood rests with the constant tacking back and forth, or resonance, among the different evocations that are described in these essays.