Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

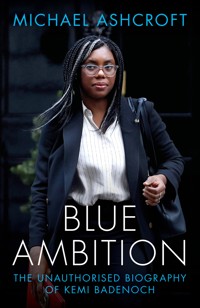

During the Conservative Party leadership contest in the summer of 2022, Kemi Badenoch made an immediate impression on the public as a politician with robust views and a strong personality. Although only a junior minister at the time, she was marked out as a rising star and, having exited the race after the fourth ballot, even as a potential future leader. From September 2022, she served in the Cabinets of Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak, combining her post as the Secretary of State for Business and Trade with that of the Minister for Women and Equalities. Badenoch's centre-right instincts and admiration for Margaret Thatcher have helped to guarantee that her popularity among the grassroots of her party remains high, yet her background is unusual by Westminster's standards. Having been born in London and raised in Nigeria, she describes herself as 'to all intents and purposes a first-generation immigrant'. She returned to Britain aged sixteen to sit her A-levels before studying computer systems engineering at the University of Sussex. She then worked in the banking sector before becoming a Member of the London Assembly in 2015 and, in 2017, entering the House of Commons as the MP for Saffron Walden. So what makes Badenoch tick? How has she achieved Cabinet rank so quickly? And what would be the implications for the direction of the Conservative Party if she did become its leader? In this meticulously researched biography, Michael Ashcroft charts Badenoch's fascinating course from relative obscurity to being hailed in some quarters as the saviour of conservatism in the UK.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

Contents

Author’s Royalties

Lord Ashcroft is donating all author’s royalties

from Blue Ambition to charity.viii

Acknowledgements

Many people kindly agreed to be interviewed for this book and most of them are named in the text. However, some asked not to be identified publicly. They know who they are and I want to express my gratitude to them for providing the various background briefings that proved so useful.

Thanks must also go to the formidable Angela Entwistle and her team, as well as to those at Biteback Publishing who were involved in the production of this book, and to Richard Assheton. And special thanks to my chief researcher, Miles Goslett.x

Introduction

In July 2022, the Conservative Party was in a state of chaos. Having been in government for a dozen turbulent years, its MPs were divided, its identity was confused and its reputation was in the gutter thanks to a series of scandals. Boris Johnson’s resignation as Prime Minister that month prompted the third Tory leadership contest in the space of six years.

Of the eight men and women who put themselves forward to succeed Johnson, the Equalities Minister, Kemi Badenoch, was arguably the least well known as far as the public was concerned. She was certainly the candidate whose decision to stand caused the most surprise in Westminster. In the space of just a few weeks, however, she made an impression as a politician with robust views and a strong personality. After seeing off four of her rivals, she was quickly hailed as a rising star. Having survived the race until the fourth ballot, she had cemented her position in the party and marked herself out as a potential future leader.

From September 2022, she served in the Cabinets of Liz Truss and then Rishi Sunak, latterly combining her post as Secretary of xiiState for Business and Trade with that of Minister for Women and Equalities. This status provided a platform on which to demonstrate her centre-right instincts and, thanks to her trenchant views on questions of race and gender identity, she attracted widespread attention. Significantly, however, it was not only the grassroots members of her party who were interested in her pronouncements but the supporters of other parties as well. They, too, seemed to appreciate that she was prepared to say things that other elected representatives were not.

Badenoch’s no-nonsense – sometimes blunt – approach was not the only thing that differentiated her. Her background is also unusual according to the expectations of British politics in general and the Conservative Party in particular. She was born in London but was raised under successive military regimes in Nigeria. She returned to Britain aged sixteen to sit her A-levels and attend university and has described herself as ‘to all intents and purposes a first-generation immigrant’. After working as a systems analyst in the banking sector and in a non-editorial role at TheSpectator, she became a Member of the London Assembly in 2015 and, in 2017, entered the House of Commons as the MP for Saffron Walden.

Having profiled several other MPs in recent years, I was keen to find out what makes Badenoch tick, to establish how she achieved Cabinet rank so quickly, to weigh up whether she has what it takes to become a Tory leader and to consider what the implications for the direction of the party would be if she did. By examining the details of her life and career with the help of some of those who know her best, this book aims to shine a light on each of these areas as the Tory Party grapples with its future direction.xiii

Some people believe that Kemi Badenoch could be the saviour of conservatism in Britain. Readers will be able to judge for themselves how likely this is.

Michael

Ashcroft June 2024

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

I have chosen to refer to Kemi Badenoch as ‘Badenoch’ throughout this book. Although she used her maiden name, Adegoke, when she stood for Parliament for the first time in 2010, since 2012 she has consistently been referred to by her married name for official purposes.xiv

Chapter 1

The Cosbys

In December 1979, a young husband and wife from Nigeria travelled thousands of miles into the depths of a London winter on a mission to ensure the baby they were expecting could be delivered in what they believed was the best environment money could buy. A few days after a consultation with a Harley Street doctor, they headed south to the suburb of Wimbledon. There, at St Teresa’s Maternity Hospital, they waited for the miracle of a new life to begin. At the time St Teresa’s, which was run by an order of Roman Catholic nuns called the Sisters of St Anne, was known as a private maternity clinic to the stars. During the 1970s, the children of the media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, the James Bond actor George Lazenby and the Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor were among those born there. On Wednesday 2 January 1980, the name Olukemi Olufunto Adegoke was added to the clinic’s record of births. Neither the child’s mother, Feyi, nor her father, Femi, could have known it then, but their decision to make the trip to Britain would prove highly significant. For even though the infant was taken straight back home to Lagos to be brought up there, she had acquired a legal 2right to UK citizenship by virtue of having been born on British soil. Ultimately, this status cleared the path for her to return to London as a teenager in the 1990s, to make a life for herself in this country and, in 2017, to become an MP, which she did under her married name, Kemi Badenoch.

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, it was not unusual for Nigerian women – nor, indeed, those from a range of other countries who could afford the airfare and medical bills – to opt for treatment at the appealingly old-fashioned St Teresa’s. It had opened in 1938 as a private hospital for patients with advanced cancer and heart disease, but after the NHS was founded a decade later, it was converted into a small maternity unit. For the next nineteen years, just over half of its seventy or so beds were funded by an NHS contract. This model made it possible for the Sisters of St Anne and their lay colleagues to care for the marginalised in society, to whom they felt a duty, as well as better-off clients who could pay. When the clinic’s NHS funding was cancelled in 1967, the nuns were determined to carry on with their work. They did so via a mixture of private patients’ fees, donations, bequests and the efforts of volunteers, looking after the needs of as many women as they could, regardless of their financial position. St Teresa’s international reputation was well deserved. The standard of care there was so high that between 1948 and 1974, only one mother died in more than 28,000 deliveries. It made a point of not being a conveyer belt-style institution but a place where women were given individual attention and, if they wanted it, time to recuperate in relaxed surroundings after the rigours of childbirth. Badenoch’s parents liked the hospital so much they returned there in order that Feyi could give birth to their next child, a son, Folahan, in June 1982. Despite the best efforts of the nuns, however, funding dried up not long afterwards and the hospital was forced to close in 31986. It has since been demolished and a block of flats has been built on its former site.

Kemi Badenoch’s birth was formally registered by her mother in the London borough of Merton the day after she was born and it is through the information included on her birth certificate that it is possible to start piecing together her parents’ backgrounds and, by extension, some details of her own upbringing. The certificate lists two addresses for Feyi Adegoke. Her British address in January 1980 was given as Flat 31, Ayerst Court, Beaumont Road, Walthamstow, in the outer reaches of north-east London. In fact, this property was where her brother, Emerson Adubifa, and her sister-in-law, Elizabeth, lived. Two weeks after recording the birth with the British authorities, the Adegokes and their newborn daughter were safely installed at the other address on the certificate – their own home, 73 Itire Road in the Lagos district of Surulere.

The Adegokes were an English-speaking couple who belonged to the Yoruba people, a west African ethnic group that makes up about a fifth of the population of Nigeria. Britain first annexed Lagos in the 1860s and from 1914 Nigeria became part of the British Empire, gaining independence in 1960. This meant that Badenoch’s parents both grew up in a British colony until they were ten or eleven years old. They had met in the mid-1970s at University College Hospital in Ibadan, the capital city of Oyo state in the south-west of the country. Femi was working there as a houseman, having graduated as a doctor from the University of Lagos in 1974, and his future wife, Feyi, was a postgraduate student specialising in medical physiology.

Although Femi’s family were practising Anglicans, his mother, Esther, was born into a Muslim family and by one account lived a rather extraordinary life. She entered into a polygamous marriage as a young woman but left her first husband, who was abusive, and 4later married Daniel Adegoke, who worked for the Ports Authority as an engineer and draughtsman. They had six children together, one of whom was Femi. She later became a successful trader, dealing in gold and jewellery and selling fabric by the yard from her shop in the largest market in Lagos. She had no formal education and could not read or write, but the wealth she built up from scratch was sufficient to have Femi educated at Ibadan Grammar School, which, like most schools in Nigeria, was fee-paying. Some of her other children attended universities in America.

Badenoch’s mother, Feyi, was one of seven children. Her father, Badenoch’s grandfather, was the Rev. Emmanuel Adubifa, a Methodist minister. Badenoch is herself a baptised Methodist, though she is no longer religious. The connection between Britain and Nigeria remained strong after independence and Badenoch’s parents were both able to travel to the UK when they were university students in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Dr Abiola Tilley Gyado, who knew them both independently, remembers, ‘We’d say to each other “Are you going on summer flight?” That meant “Are you going to London?” Students could have holiday jobs in Britain. It was considered acceptable. Kemi’s mother and I travelled to London together.’

Femi and Feyi were married in 1977 at Hoare’s Memorial Methodist Cathedral in Lagos. By then, Feyi was a lecturer at the University of Lagos’s College of Medicine, where she would go on to become a professor of medical physiology. In the early 1980s, Femi decided to open his own private GP’s practice, which he combined with working in a teaching hospital. Private healthcare options have always been prevalent in Nigeria because of its underfunded state healthcare service and over time Femi’s clinic, which was called Iwosan, meaning ‘healing’, began to thrive. It was based on 5the ground floor of 73 Itire Road, which Femi eventually inherited from his mother. The young family lived in the three-bedroom flat upstairs and this was the place Kemi Badenoch called home for the first thirteen years of her life.

After the civil war that had scarred Nigeria in the late 1960s had ended, the 1970s was a boom decade. Lagos, which remained the capital until 1991, was at the centre of this economic upswing. Oil had first been discovered in Nigeria in 1956 and over the next fifteen years production grew steadily to a peak of 2.3 million barrels per day, turning it into the wealthiest and most diverse nation in Africa. Indeed, Nigeria became so prosperous that it was able to export food. Inevitably, the population of Lagos, its largest city, increased at a dizzying rate, from approximately 2.5 million in 1980 to almost 5 million by 1990, as it attracted people from all over the African continent seeking work. Some of the money generated by the oil industry found its way to Badenoch’s father’s clinic, which secured contracts to treat the employees of various oil companies, and it continued to flow steadily during the earliest years of Badenoch’s life. Yet friends say that the Adegokes remained pretty typical among middle-ranking educated Yoruba families living in Lagos at the time, being comfortable rather than truly affluent. There was certainly nothing ostentatious about their life. They had no driver, for instance, though some middle-class families did, and they had no domestic staff either. The children were expected to help their parents keep the house tidy.

Badenoch’s father was not the only person in the family who enjoyed professional success during the 1980s. In 1985, her mother, Feyi, was awarded a fellowship to a medical college in Omaha, Nebraska. By then Kemi and Folahan had been joined by a sister, Funlola, born in Lagos in 1984. Feyi and the three children moved 6to America for almost a year. When they returned to Africa in 1986, it was time for Badenoch to start school. One of the most enduring legacies left by the British in Nigeria is its education system, so much so that even today the two countries are broadly in line with each other when it comes to schooling. Badenoch first went to St Saviour’s, a traditional primary school for children up to the age of eleven. Her father had a strong interest in music and enjoyed listening to a wide range of styles, from the Nigerian musician Fela Kútì to Frank Sinatra. In her spare time, he taught her to play the piano. She also enjoyed swimming and reading books written by Enid Blyton, notably the Famous Five and Secret Seven series. As a young girl she was keen on debating, even being asked to take part in a televised children’s discussion programme aimed at ten-year-olds. Although she was seen on camera in the studio, she was not asked to participate in the debate, to her annoyance.

If her primary school years were generally straightforward, however, her secondary school career, which began in 1991, was less settled. It opened with a brief spell at the Federal Government Girls’ College Sagamu, a state-run boarding school in a rougher town about forty miles north of Lagos. It was one of fourteen federal government colleges established in the newly independent Nigeria with the aim of fostering national unity. Badenoch hated it and left within the space of a year. ‘I had a very tough upbringing,’ she told the Evening Standard of this chapter of her life in 2018.

We all had to do something called ‘manual labour’. Mostly it meant getting up at 5 a.m. and cutting grass endlessly. Everyone had their own machete. Because that’s how you cut grass in Africa. There were no lawn mowers. We had to tend our own patches. I still feel as if I have got the blisters.

7As much as she resented having to do physical work before sunrise, it is just as likely that she felt out of place at the school and missed her parents. By the standards of a patriarchal society such as Nigeria’s in the 1980s, her father is said to have taken an unusually modern approach to bringing up his children, often making breakfast for them in the morning and helping them with their homework in the evening. As he lived and worked in the same building, he had more time than many fathers would have done to devote to them and the bond between him and his eldest daughter was always strong.

Having persuaded her parents to withdraw her from her boarding school, Badenoch was next sent to Vivian Fowler Memorial College, a fee-paying Catholic school close to the family home. In 1993, when she was thirteen, the family left 73 Itire Road, which had by then expanded to incorporate an inpatients section and had therefore become a small hospital, and moved to a four-bedroom house not far away in the Gbagada area, where Badenoch’s mother still lives. At about the same time, Badenoch switched schools again, this time enrolling at the International School Lagos (ISL), a co-educational college that catered mainly for the children of university staff. It was based within the university campus, had decent facilities and, usefully, its fees were heavily subsidised for the offspring of university employees. When Badenoch arrived, her younger brother was already a pupil there.

In a nation in which it is estimated that at least 500 languages are spoken, English is Nigeria’s lingua franca and lessons in every school that Badenoch attended reflected this fact. She communicated with most of her friends and peers in English as well, even though Yoruba was her first language. Indeed, owing to her parents’ jobs, her grasp of both spoken and written English was apparently better even than that of some of her teachers. Dr Gyado sent her 8own children to ISL. ‘It was a brilliant school,’ she says. ‘Kemi was a lot of fun, but she was also inquisitive. She took her studies very seriously. She wasn’t very sporty – that may have been because the environment didn’t allow it at school. The school was quite academic.’

One friend Badenoch made during her time there was Taiwo Togun. ‘We both arrived at ISL in Form 4,’ Togun remembers.

Kemi started a few days before me. I met her on my first day. She just came into the class and introduced herself to me. We found out that our parents went to medical school at about the same time, her mum worked in the college of medicine, my mum worked in the college of medicine, so there was a lot in common. She was brilliant in the things she was interested in. She loved English. She was probably one of the best students in our English class. And I think she really liked maths as well. I don’t think she had any issues in school academically.

Togun says that Badenoch was not a rebel but she could be outspoken. ‘If there was something she didn’t agree with, she would respectfully tell the teacher, but I wouldn’t call her a rule-breaker,’ she says. ‘I think her parents probably instilled a certain amount of confidence in her.’ As well as being capable in the classroom, she was also a skilled chess player, winning a national girls’ competition when she was seven years old. Some might argue that learning chess at a young age would come in useful years later when coping with the political scheming of Westminster, to say nothing of letting her get inside the minds of others. Yet Togun says that at the time they met, Badenoch’s ability to checkmate her opponent’s king did not simply reflect her enjoyment of the game; it also acted as a unifying force among their year group. 9

I wouldn’t call her a ringleader, but she had friends in all classes. We had some guys who were the brilliant boys in school and Kemi became their friend by playing chess. I think her dad taught her when she was a child and once the boys became her friend, they became every other person’s friend. I think what endeared her to them is she would beat some of them and they thought, ‘Who is this girl?!’ Sometimes when people are very smart they tend to talk to smart people only, but she broke that idea, so we all became friends – girls and boys, brilliant, average, struggling.

Togun believes that Badenoch’s mindset from childhood to the present day has always been: ‘I’m probably the best thing in the room, you just don’t realise it, and you will realise it sooner or later.’ The way Togun describes this attitude is nuanced, however. She doesn’t necessarily mean that Badenoch believes herself to be brilliant in all that she does; more that Badenoch feels that her inner strength will eventually come to the fore, an outlook that has helped to bolster the conviction that her parents always encouraged in her. Equally, her instinct to bring people together, which is another form of networking, could be seen as a self-protective measure after the upheaval of being sent away to a boarding school she loathed and which clearly left its mark on her. If this is true, it is a trait that has so far served her well in politics.

During their early teenage years there was a limited amount of socialising outside school hours but, according to Togun, none of the girls in their class had a boyfriend and the idea of hanging around in shopping malls or cafes in the way that, say, European or American children might was absolutely not par for the course in 1990s Lagos. Apart from anything else, many middle-class parents were conservative and quite strict. Badenoch has said that her own 10family was very close. Unlike the parents of some of her friends, hers remained married, providing a solid platform on which she was able to build. Her family was also fairly relaxed and informal by Nigerian standards and they were apparently known jovially as the Cosbys, after the 1980s American television comedy The Cosby Show, whose main character, played by Bill Cosby, was a doctor in New York. Still, there were boundaries that had to be observed. ‘I didn’t really go to parties,’ Togun says.

Our parents didn’t really allow us to go. I don’t think Kemi was allowed to go either. Maybe she went to one or two, but her father would be outside, if I remember correctly, or she was only allowed to spend thirty minutes there. Because everyone’s parents would say, ‘What are thirteen- or fourteen-year-olds doing outside their house in the evening?’ From six o’clock, my parents said they didn’t allow it, so I don’t think Kemi’s parents allowed it. It wasn’t about security. It was more ‘What are you doing? Why do you need to be at a party?’ Their attitude was ‘That’s not what we do. You can wait until university. There’s plenty of time to do all of that. Just focus on your schoolwork.’

Badenoch spent quite a bit of her free time with cousins and family friends. ‘It was about instilling values,’ says Togun. She remembers middle-class life in Lagos thirty years ago as conventional and, like many other cities in developing nations, simpler than it is today. She says that from the age of thirteen, Badenoch lived in what she remembers as being a fairly modest house in a quiet cul-de-sac. It had no garden to speak of. Churchgoing was encouraged and there was little in the way of outside entertainment. 11

Lots of people had television, but it wasn’t broadcast 24/7. It would come on at 4 p.m. and go off at 11 p.m. There were cinemas when my parents were in school, but by the time we were born there were no cinemas until the 2000s, I don’t think. I probably didn’t see a cinema in Lagos until well after I graduated from university in 2004 or 2005.

Furthermore, people did not tend to go on holiday often and diets were monotonous, consisting mostly of soup and rice. ‘Kemi was the first person I met who used to eat wheat bread, or brown bread,’ she says. There were few fast-food outlets or anything similar because Western restaurants had not reached Lagos by that point. ‘We had Mr Biggs, which used to sell doughnuts, meat pies, sausage rolls, even chicken pie,’ says Togun. ‘Chicken used to be a luxury then. You only ate chicken once a week.’ She adds that most people had to be very careful with their money. ‘My parents had to be, and I’m almost certain Kemi’s parents had to be because we had similar backgrounds. So you would not get to do a lot of things that you wanted to do, because you had to spread the income you had over three or four children.’

Nigeria has long been regarded as a risky place to visit, but it would probably be difficult for many Britons to grasp just how volatile it could be when Badenoch was growing up there during the final quarter of the twentieth century. It was an era when the country ricocheted from coup to coup, resulting in three decades of military juntas, which were active until the turn of the millennium. Almost nobody was immune to some sort of disruption during this fractured period. Thanks to the near-constant state of economic and political flux, corruption among the top tier of the government and 12civil service was the rule rather than the exception and the threat of violence hummed menacingly in the background.

In the 1970s, the government had been able to borrow heavily based on its projected petroleum revenues, which by the middle of the decade accounted for almost half of its gross domestic product. President Murtala Muhammed, who took office in July 1975, was in power when some of these loans, which were earmarked for a series of modernising projects, were made. After Muhammed was assassinated in February 1976, General Olusegun Obasanjo succeeded him, serving as Nigeria’s head of state until 1979. In that year, Shehu Shagari became Nigeria’s first democratically elected president, marking a brief democratic interlude under what became known as the Second Nigerian Republic. Following another coup in 1983, in which the hardline Major-General Muhammadu Buhari was installed as the military head of state, inflation began to soar and living standards fell as the global oil price fluctuated. From the mid-1980s, Nigeria defaulted on its debts and hundreds of thousands of west African economic migrants who had settled there were expelled, in part to ease the job market. In 1986, Nigeria was forced to embark on a structural adjustment programme approved by the International Monetary Fund, necessitating limited public spending and devaluation of the national currency, the naira. By the late 1980s, when Buhari had himself been overthrown by General Ibrahim Babangida, its economy was weighed down by about $30 billion of foreign loans and the World Bank had demoted it to the status of a poor nation. This was the shadow in which Badenoch was raised.

In one sense, growing up under a series of military regimes was second nature to Badenoch, her siblings and her friends. Quite simply, they knew nothing other than the instability under which 13most Nigerians lived. At the same time, her middle-class family was relatively lucky because they were largely insulated from the disorder. When the value of Nigeria’s currency began to drop and exchange rate controls and capital controls were imposed, restrictions were by necessity imposed on family life, but in essence they remained in a reasonable position compared with many of their fellow citizens. With that said, these tensions undoubtedly affected her. In her maiden speech in the House of Commons in 2017, Badenoch spoke of ‘living without electricity and doing my homework by candlelight, because the state electricity board could not provide power, and fetching water in heavy, rusty buckets from a borehole a mile away, because the nationalised water company could not get water out of the taps’.

This was not an exaggeration, says Taiwo Togun.

People didn’t have generators then the way they do now. If the light went, you had to use candles or lanterns and when there was no light, there would be no water, so you would have to fetch water, sometimes from within the complex, sometimes from the next one. Everybody said, ‘The government should do this, the government should do that, why don’t we have water, why don’t we have light?’ Then everybody started providing for themselves, but that didn’t start until maybe 2000 or 2001.

It is somehow appropriate to find that, amid the disorder, the schoolgirl Kemi had already become aware of a female leader who had taken a country that was in decline and, through what she called ‘the politics of conviction’, transformed it. That person was, of course, Margaret Thatcher. In fact, Badenoch has claimed that when she was young, she held Thatcher in such high regard that 14she would invoke her name during discussions with members of the opposite sex. ‘They say a prophet is never loved in their own country,’ she told Nick Robinson of the BBC in 2020.

Growing up in Nigeria – this is a country that is very patriarchal … There were competitions that the girls weren’t allowed to take part in because we were girls. There were privileges that the boys were given which we weren’t given. And they would laugh at us and say, ‘Girls can’t do this, girls can’t do that.’ And you’d just say two words: Margaret Thatcher. And there was nothing they could say in response to that. She was inspirational.

Just how inspirational Thatcher was to Badenoch would become clear, for as Nigeria’s economic and political prospects worsened, her parents invited her to help them make a decision that would have profound consequences for her personally. Unbeknown to anybody at the time, the upshot of this was that Badenoch would one day meet Thatcher and, remarkably, would subsequently sit around the same Cabinet table from which her political heroine had run Britain for eleven and a half years.

Chapter 2

Golden Ticket

By 1995, Nigeria was widely considered to be a pariah state. Aside from its economy being in the doldrums, human rights abuses were rife and it was rapidly moving up the scale of the most dysfunctional countries in the world. Matters reached a head on 11 November when it was suspended from the Commonwealth following the executions of nine environmental activists who had been incarcerated by the government on contested charges of murder. Among those hanged was Ken Saro-Wiwa, an author who had become one of the regime’s fiercest critics. International condemnation followed the killings, with Western nations recalling their ambassadors and the World Bank withdrawing its backing for a multi-million-dollar development deal. Even Robert Mugabe, the corrupt President of Zimbabwe, was critical of Nigeria for having imposed the death penalty so arbitrarily. As Badenoch’s parents watched their country sink ever lower, they had begun making plans to remove their eldest daughter from the turmoil so that she could live abroad.

In fact, by the mid-1990s Badenoch’s parents were, like much of Nigeria’s small but historically prosperous middle class, living in reduced circumstances themselves. Under General Babangida, the 16head of state, a presidential election had been held in June 1993. Although the result was never officially declared, Chief Moshood Abiola of the Social Democratic Party defeated Bashir Tofa of the National Republican Convention, managing to transcend the complicated politics of ethnicity and religion that had plagued Nigeria up to that point. The majority of voters had been pleased about Abiola’s apparent victory, but this outcome appeared to go against Babangida’s interests and the poll was annulled. Yet another coup followed in November 1993, in which the merciless kleptocrat General Sani Abacha seized power. All hope of a return to democracy and security was dashed. Instead, the country slid into a long cycle of strikes and protests. Many of these demonstrations took place at universities, including the University of Lagos, where Badenoch’s mother worked. It was closed for the best part of a year. Badenoch’s father was not immune to professional problems either, as the oil company contracts that had kept his business buoyant for more than a decade were terminated and, in a double blow, many of the nurses who worked at his clinic relocated to Britain and Australia. Money was tight and the future appeared to be bleak. Yet one consequence of Badenoch’s parents having grown up in a British colony was that they felt their link with Britain itself was strong. Indeed, it could be said that in some respects they, in common with many other educated Nigerians, viewed Britain almost as an extension of their own country.

‘Anyone who had the chance to get out of Nigeria left,’ says Feyi Fawehinmi, a distant cousin of Badenoch, of this period.

The economic crisis made life very tough for everyone in the 1990s. People thought it was so bleak and the country had no future. People’s circumstances really changed. They didn’t take 17anything for granted any more. You had to fight for everything and rely on friends. Inflation ravaged savings. The damage done in the 1990s destroyed a lot of the Nigerian middle class. Kemi’s family was a victim of that. My family was a casualty as well. At that time the greatest love that parents could show their child was to get them out of the country. If you had the means to do it, you would.

It wasn’t just the dire economic situation that had an effect on people’s outlook. Fawehinmi goes on to say that the sense of lawlessness in Nigeria also hastened many people’s departure. ‘What was called “jungle justice” was common when we grew up,’ he remembers. ‘For example, if someone was caught stealing, they might be doused in petrol and set on fire by a vigilante mob. These things have informed who Kemi is.’

Badenoch’s 16th birthday fell in January 1996 and she sat the Nigerian curriculum’s equivalent of GCSEs at around that time. She also took the SAT exam, a key component in the process of applying to an American university. She has said she achieved a high enough score in it to win a partial scholarship to study medicine at Stanford University in California, but because her parents were unable to afford to send her to America, they decided instead to take advantage of the fact that she had been born in London.

It has been hinted at in some quarters that Badenoch’s parents made a conscious decision to have their first two children in Britain not only to guarantee their safe arrival in a reputable hospital but also to secure each of them a British passport. This is a challenging claim which warrants scrutiny. Whenever Badenoch has been asked why she was born in Britain, she has usually explained that her mother had an ‘obstetric referral’ to a private doctor in Harley 18Street and in December 1979 returned to London to give birth at the private St Teresa’s clinic. The idea that her parents were NHS ‘health tourists’ is therefore inaccurate, for no British taxpayers’ money was spent on the medical treatment received by her mother. And yet it is the case that anybody born in the UK before 1 January 1983 had an automatic right to a British passport, regardless of their parents’ nationality or permanent residence. The question is, therefore, whether Badenoch’s parents were aware of this rule when she and her brother Folahan were born in 1980 and 1982 respectively.

As described in the previous chapter, Badenoch’s late uncle Emerson – that is, her mother’s brother – was already living in London at the time of her birth, and his home address in Walthamstow even features on her birth certificate. But Badenoch has rejected any suggestion that she was what she has called an ‘anchor baby’, a pejorative term referring to a child who is born to a foreign mother in a country which offers citizenship as a matter of routine. In an interview with TheTimesin February 2024 she said, ‘It’s very, very aggravating when people say my mother had me here to be an “anchor baby”. She’s the most incorruptible woman.’ Indeed, Badenoch’s parents were supposedly unaware that she and her brother were entitled to become UK citizens until this was pointed out to them by a family friend when Badenoch was fourteen years old. On discovering that her parents had applied for a visa to visit London which had apparently been declined, this unnamed friend is said to have explained to them that Badenoch and her brother were technically British on the basis of where they were born and so an application for two passports in their names should be made instead. Badenoch told a 2022 podcast interview with TheSpectatorthat her mother found this suggestion ‘absolutely preposterous’ initially but when she looked into the law and realised there was nothing 19standing in the way of her first two children exercising this right, the relevant paperwork was completed and dispatched. ‘I remember the day that the passports arrived,’ Badenoch recalled. ‘I always tell people it was like in CharlieandtheChocolateFactorywhen you open the chocolate bar and there’s the golden ticket … All of a sudden these pink passports arrived. It was amazing.’ According to her, the fact that she was able to assume a British identity at a time of her choosing was down to nothing more than ‘fate’. Whatever the truth, it is undeniable that she played no part in deciding where she came into the world and that for her to have been born in London was quite simply her great good fortune.

Badenoch has said that even though she had not lived away from home before, other than for a brief spell at her state-run boarding school when she was eleven, she was desperate to leave the havoc of Nigeria behind. Having grown up in a country where ‘tipping’ the police simply in order to go about one’s daily business was considered normal, the attractions of Britain’s liberal society would have been obvious. The idea of beginning a new life in London aged sixteen does not seem to have daunted her in the least, despite the fact she had never even travelled on public transport before. An escape route having been found thanks to Britain’s citizenship laws, she and her father made the necessary travel arrangements in the summer of 1996. ‘Dad spent several months’ pay on my plane ticket,’ she recalled in an interview with the Daily Mail in 2017. ‘We went to the travel agent with all his savings stuffed in a plastic carrier bag. He had £100 left when he’d paid for my ticket, and he gave it to me to take to England. So that’s all I had when I arrived.’

Her first port of call in London was 81 Springfield Avenue, a five-bedroom house on the outskirts of Wimbledon. It had been bought not long before by Dr Abiola Tilley Gyado, her parents’ 20longstanding friend who had also been the chief bridesmaid at their wedding. Dr Gyado had been the director of Nigeria’s Aids programme during the early 1990s before moving to London to work for the charity Plan International. She had three children who attended boarding schools outside the capital, so she and Badenoch lived together during the week. ‘People would talk about people “checking out” of Nigeria,’ Dr Gyado says of that period of Nigeria’s history. ‘That was the language used for those who were leaving. Kemi’s parents stayed because they still had things to do there, so she came on her own. She wanted to experience another life. I knew Kemi before she was born. She was like a child to me.’ Indeed, Badenoch referred to her as her ‘aunt’, even though they were not actually related in any way.

Many middle-class parents in Nigeria at that time hoped that their offspring would opt for one of four careers when they grew up: medicine, law, accounting or engineering. Expectations were always high and, as professionals themselves, Badenoch’s mother and father were no different. Their desire was that she would eventually read medicine at a British university and, initially, she seems to have gone along with this idea. She quickly set to work finding a suitable school at which to study for her A-levels and settled on Phoenix College, a state-funded sixth-form college for 16–19-year-olds that was within walking distance of Dr Gyado’s house. She began there in September 1996. Set in fifteen acres of grounds and with buildings dating back to the 1930s, it had previously been called Merton Sixth Form College, but its name was changed in 1990 following a reorganisation of the area’s secondary education provision. It was underwritten by the Further Education Funding Council for England, the Department for Education body that was in charge of the sector at the time, and it operated outside local authority control. By 21the standards of sixth-form colleges in the 1990s, it was considered small, having fewer than 400 students on its roll. Facilities included several tennis courts, a sports hall, a cafeteria, a library and a drama studio. Ultimately it proved unsustainable to run and it closed in 2000 after being in operation for only a decade.

One former member of staff who agreed to be interviewed for the purposes of this book describes it as a happy place, even if it was not at the top of the tree academically. ‘There was a fairly low bar to entry – I believe that students needed to have at least four GCSEs at C grade or above,’ says this person, who asked not to be named. ‘The college wasn’t exceptional in any way. There were only between 100 and 150 full-time students in each year and about forty staff.’ It is understood that many of the students were there to gain GNVQs or to retake GCSEs rather than to study for A-levels and so class sizes for those, like Badenoch, who wanted to matriculate were small.

According to a prospectus dating from the mid-1990s, students at Phoenix College were encouraged to develop their independence, meaning that the college was in some respects closer in style to a small university than a school. There was no uniform and students and tutors were on first-name terms. ‘We offered pastoral support,’ explains the former staff member. ‘We had a vice-principal who looked after the welfare of the students and every student also had a tutor, but the students only had to be there when they were attending lessons.’

Although Phoenix College appears to have been a neat solution for Badenoch insofar as it was conveniently located for her, and free of charge, her time studying there does not seem to have been entirely without tension. Having grown up in Nigeria’s professional middle class, and being used to the rigidity of that country’s traditional education system, in which pupils were expected to look 22smart and behave well at school or face disciplinary action, she seems to have had some difficulty acclimatising to the looser ethos of this particular south London institution. ‘What struck me was how foul-mouthed some of the students were,’ she told the Daily Mail in 2017.

I’d never used the F-word – my grandfather was a reverend and we were raised as strict Christians – and I found it shocking and scary that young people spoke flippantly, even rudely, to adults. This was an area of London with a large black population, yet it was a black culture I didn’t recognise. A lot of damage has been done by accepting this kind of behaviour, shrugging it off as the inevitable corollary of deprivation and poverty.

It wasn’t just some of her fellow students who seemed to bother the teenage Badenoch. She also believed that some of the staff were discriminatory. ‘Teachers treated us differently from the white people at the college,’ she told the Daily Mail in 2019.

They assumed we had it tough. They couldn’t tell the difference – and this is where judging by skin colour is a terrible thing – between someone who had perhaps grown up in a very disadvantaged family and had serious challenges, and someone from a stable family who had loads of opportunities. You would have people who quite clearly had special needs – who were autistic, I recognise that now – and it would be like, ‘That is just how black people behave.’

Moreover, other members of staff had what she remembers as a depressingly defeatist attitude. She opted to study biology, chemistry 23and maths at A-level. On the face of it, sufficient grades in these subjects would probably have allowed her to follow in her father’s professional footsteps. Since the University of Oxford was, apparently, the only British university she had heard of when she arrived in London, she has said that it was her aim to study medicine there rather than anywhere else. Over the course of the six terms that she worked towards her A-level exams, however, various barriers presented themselves. One story she has told on several occasions is that a senior member of staff at Phoenix College actively steered her away from this aspiration altogether. Having explained that she wanted to be a doctor, and that both of her parents were doctors, she was apparently told, ‘Medicine is really, really difficult. Have you considered nursing?’ She said that this epitomised ‘the culture of low expectations that I’ve learned, being in the UK’. After this small humiliation, she and a Chinese student went to see another member of staff at the college to seek their advice. As she later told a TED Talk audience:

We both said, ‘We want to go to [Oxford] university, what do we do?’ And they said, ‘There’s no point in applying because they’ll never take you. They don’t take people like you. They’re elitist institutions and all they want are posh people, children of their friends and so on. There are many other schools you can go to that’ll be just as good.’ So I didn’t apply [to Oxford] because that’s what the teachers told me.

More than twenty-five years after Badenoch left Phoenix College, it would be almost impossible to prove or disprove this account, but the former staff member who agreed to be interviewed says that he is quietly sceptical of it, calling it an anecdote that sounds 24‘trite’. He goes on: ‘I can certainly think of one student who went to Cambridge.’ He did go to the trouble of asking a former senior colleague whether they remembered Badenoch, but, like him, they did not. ‘If she was quiet and diligent she probably wouldn’t have been that memorable,’ he concludes. ‘We had nice students and nice staff. There was a good relationship between the two.’ Dr Gyado offers a slightly different perspective, however. ‘Kemi talked to me about the poor behaviour of other students,’ she confirms. ‘I think we probably arrived at the conclusion that it was because it wasn’t a fee-paying school. Fee-paying schools can open up a lot of possibilities.’

Free IT training was also on offer at Phoenix College, which, bearing in mind the internet was in its infancy in the 1990s, was undoubtedly a bonus. Perhaps because of the perceived resistance to her plans to study medicine, or maybe as a result of a growing sense of her own independence, Badenoch changed her mind about her career plans halfway through her A-levels, deciding that she no longer wanted to become a doctor. Instead, she said, she wanted to work in computing. She had apparently begun to learn the art of computer coding at an extraordinarily young age and had always enjoyed problem-solving. She told her parents, with whom she would speak by telephone, and they were disappointed but accepting. The only tasks facing her were to find a computing course at a university that appealed to her and then to secure the requisite A-level grades.