Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

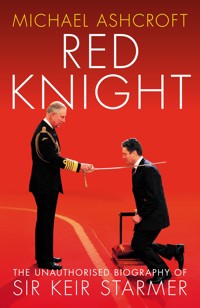

Sir Keir Starmer made the leap from Leader of the Opposition to Prime Minister in only four years, one of just a handful of politicians to have done so since 1945. Yet the landslide majority that Labour secured under him in July 2024 has been described as 'loveless' and his first months in Downing Street were overshadowed by rows and controversies, turning what should have been a political honeymoon into a period of sustained turbulence. In this fully revised and updated edition of his 2021 biography, Michael Ashcroft traces how Starmer went from schoolboy socialist to radical lawyer and Director of Public Prosecutions before – aged fifty-two – becoming an MP, then Labour leader and ultimately the occupant of No. 10. Revealing previously unknown details which help to explain what makes Starmer tick, this careful examination of Britain's first Labour Prime Minister for fourteen years offers voters the chance to assess his character and his political instincts. Having turned his party into an election-winning machine, his goal is to transform Britain into one of the most progressive states in the world. Does he have what it takes to succeed?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 767

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iii

Contents

vi

Author’s royalties

Lord Ashcroft is donating all author’s royalties from Red Flag to charity.viii

Acknowledgements

Among the scores of people who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this book, some asked not to be named publicly. For this reason, it is not possible to identify here everybody who deserves thanks; suffice it to say their background briefings were extremely useful.

The following people were notably generous with their time and help by assisting or advising in different and important ways: Prof. Bill Bowring, Sean Davey, Peter Burgess, David Jones, David Johnson, Mark Dixon, David Wharton, Margaret Crick, David Griffith, James Hanning, Safia Bugel and the staff of Haringey Archive and Local History Centre.

Thanks must also go to the formidable Angela Entwistle and her team, to Kevin Culwick and to those at Biteback Publishing who were involved in the production of this book. And special thanks to my chief researcher, Miles Goslett.x

Introduction

When this book was first published as Red Knight in the late summer of 2021, Sir Keir Starmer’s political prospects looked distinctly shaky. His principal problem was that after barely eighteen months as Labour leader, nobody could be sure what he stood for. In his defence, he had been busy. First, there was the job of trying to patch up a Labour Party that was still badly damaged by its poor showing at the 2019 general election. On top of that, he had to oppose a Conservative government led by Boris Johnson that basked in the glory of an eighty-seat majority – a task that was hugely complicated by the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic. To compound matters, he had just suffered a string of disastrous local election results and the humiliation of losing the solid parliamentary seat of Hartlepool to the Tories in a by-election. Furthermore, his dysfunctional relationship with his deputy, Angela Rayner, had left him open to mockery.

His critics, chief among them Tony Blair, did not hold back. What was his overall plan, they demanded? What were his economic policies? And was he as dull and plodding as he seemed? This disparagement prompted doubts in some quarters about whether Labour would even survive under his leadership. What nobody knew at the time was that he had already had a crisis of confidence and come close to resigning. Only the soothing words of his wife, Victoria, and the advice of his loyal political aide Morgan McSweeney stopped him throwing in the towel. Then xiihis fortunes changed. In November 2021, the Conservative government embarked on the long journey of self-destruction that ended, ultimately, in the ruling party’s worst ever general election defeat in July 2024. Starmer was installed as the first Labour tenant of 10 Downing Street for fourteen years.

Making the transition from shadow Cabinet minister to Leader of the Opposition to Prime Minister in the space of a single parliamentary term was no mean feat. With the help of a small group of trusted lieutenants, he achieved it by jettisoning MPs and party members whose hard-left political opinions he feared might stand in the way of regaining power, and by giving the public the impression that Labour had returned to the centre ground. All this happened with miraculously little damage being sustained to Labour’s image. Starmer’s ruthlessness surprised many – not least one of his former colleagues in Doughty Street Chambers who told me he’d always assumed he was a ‘political wet’. Yet certain thoughts nagged. To what degree was the 2024 general election result a positive vote for the Labour Party as opposed to being just an anti-Tory vote? The turnout was not quite 60 per cent and Labour’s share of the vote was a mere 33.7 per cent – the lowest of any majority party on record. Put another way, 80 per cent of registered electors did not back Labour at the ballot box. What’s more, were Starmer and his top team ready for government? The answers to these questions soon showed themselves.

On paper, Labour’s haul of 412 MPs against the Conservatives’ rump of 121 MPs should have marked the beginning of a period of supremacy for the new Prime Minister. Yet his political honeymoon was cut drastically short and his – and Labour’s – poll ratings plummeted during his first 100 days in office. In part, this was thanks to a series of self-inflicted blunders including manifesto breaches and sleaze scandals. These missteps raised doubts xiiiabout Starmer’s integrity and his political nous. Confidence in him suffered. More widely, he is also felt to have failed to carve out a reputation as an interesting and original thinker. Most crucially, on the economy his government stands accused of returning to the default setting of previous Labour administrations, via Chancellor Rachel Reeves dishing out public sector pay rises while imposing higher taxes and more bureaucracy on business and enterprise. In doing so, Starmer’s own claim of wanting to put economic growth at the heart of his government’s programme has proved hollow. Additionally, in defiance of the millions who voted for Brexit in 2016, he has forged closer ties with the EU. And his insistence on trying to make Britain net zero by 2050 is set to cost taxpayers multiple billions of pounds. After nearly a year in power, it is not difficult to see why his government is scrambling for consistently better poll ratings, even taking into account the role he began to play in world affairs at the time of going to press. For very different reasons, his position is weak again, just as it was in the late summer of 2021.

Little was then known about Starmer other than that most of his adult life had been spent outside elected politics, as a barrister from 1987 until 2008 and as the Director of Public Prosecutions from 2008 to 2013. He became a Labour parliamentary candidate in December 2014 and entered the Commons in May 2015 at the relatively late age of fifty-two. Five years afterwards, he was elected Labour leader. In Red Knight I sought to find out more about him, but it became clear in the early stages of the project that he did not want the book to be written. Indeed, he actively obstructed it, telling friends – who then told me – that he would rather they did not co-operate. I wrote in 2021 that while I am the first to accept that everybody is entitled to a private life, I also believe that any politician who wishes to present themself to the country as the Prime Minister in waiting should have a skin thick enough xivto be untroubled by a study of their character. He seemed to think it would be acceptable for him to stand for the highest office in the land without some probing questions about him being asked in a truly unrestrained way. This reaction confirmed that he is by nature cautious and defensive. He is also uncomfortable with the rough and tumble of politics.

As it turned out, many people who have known Starmer at various stages of his life were happy to help. Some did so publicly; others preferred to do so anonymously. Their recollections contributed to the book’s accuracy. This can be stated with certainty because in 2023 Starmer agreed to give a series of interviews to the journalist Tom Baldwin. Their conversations formed the basis of what became Baldwin’s sanctioned biography of Starmer. Much of the independently researched detail found in the pages of Red Knight also features in Baldwin’s book.

Starmer is hard to fathom at the best of times but is easily portrayed as a man of contradictions. Having attended a fee-paying school and the University of Leeds, gone on to study for a year at the University of Oxford, become a successful barrister, been appointed Director of Public Prosecutions, accepted a knighthood, entered the Commons and now become Prime Minister, he is undeniably a member of the establishment. And yet despite having succeeded in life thanks to his own hard work, he seems always to be at pains to distance himself from the establishment by speaking so often of his ‘working-class’ roots and his socialism. It is as though he is worried that the public will think less of him for having done well off his own bat.

This perception of him facing in two directions at once dominated his first years in Parliament. Having become a knight of the realm in 2014, he made it clear that he would rather not be addressed as ‘Sir Keir’. When he took up the post of shadow Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union from 2016, he xvpromised to honour the Brexit referendum result, only to demand a second vote later on. He remained in the shadow Cabinet when Labour was plagued by allegations of antisemitism but did not speak up publicly in any meaningful way for the Jewish community – despite his wife’s Jewish background. He campaigned for Jeremy Corbyn to become Prime Minister twice, at the 2017 and 2019 general elections, and then denounced him, saying he had never considered him a friend and was always ‘certain that we would lose the 2019 election’. As Leader of the Opposition, he was at pains to portray himself as being of the left but, under him, Labour was rebuilt by those on the party’s right. This has naturally made some wonder whether he was interested in gaining power for the sake of it, or whether he is driven by something more principled.

Starmer calls himself a socialist and yet, although well-off in his own right, he and his wife were happy to accept thousands of pounds’ worth of clothes paid for by the Labour donor Lord Alli, a multi-millionaire proponent of capitalism. His key election promise was to grow the economy, but his government’s policies appear to have hindered that aspiration. As for his popular appeal, all the signs are that despite his image as a football-mad man of the people, he struggles to connect with the electorate – and they have difficulty identifying with him. Most polls conducted since July 2024 have served as a reminder that he has never been as liked or as respected as Britain’s most successful leaders have been. His lack of captivating communication skills has not helped him, though, in a way, it does make his victory in 2024 more remarkable.

Having looked at Starmer’s life before he entered No. 10, it seemed only right that I should chart his first months as premier. As well as tracking his progress from 5 July 2024, the day he formed his government, I have revised and updated sections of xvithe original text. It struck me as appropriate to retitle the book Red Flag in recognition of the Labour Party’s traditional anthem and, at the time of writing, to acknowledge the concerns of so many voters, pollsters and commentators about what Starmer’s rule could mean for the future of Britain.

Sir Keir Starmer reached the political summit as quickly as he could have done. The points arising are: how did he achieve this; what has he done with the power he has gained; and what is the outlook for Britain under his stewardship? This book sets out to answer these, and other, questions.

Michael Ashcroft

April 2025

Chapter 1

‘The posher the voice, the more vulgar they are’

Any mention of the county of Surrey tends to inspire in some people’s minds the hackneyed idea that everybody who lives there owns a large house, works in the City of London and belongs to at least one members-only club. This stereotypical view, given credence by the label that the area is quintessential Stockbroker Belt territory, certainly has a ring of truth to it. Yet it is also undoubtedly simplistic. The upbringing of the self-declared socialist Sir Keir Starmer, who was raised and went to school in Surrey, serves as adequate proof that it has also always been home to people of more ordinary means, no matter how aspirational they are. The question becomes whether Starmer’s background can be considered truly working class, as he has often been at pains to suggest when making his pitch to the electorate, or whether he is really a ‘posh Trotskyist’, as some newspapers have claimed.

Tracing his paternal line back to the early nineteenth century, it is clear that four of the five generations of Starmers that came before his were solidly working class. His great-great-great-grandfather, George Starmer, was born in Lincolnshire in 1819 and was a labourer there until his death in 1870. His son, also called George, began life as a farm labourer in the same county before marrying a servant, Matilda Buswell, and moving to Yorkshire in 1890, where he was employed as a gamekeeper and then 2became a farmer. Their son, the colourfully named Gustavus Adolphus Starmer, who was Keir’s great-grandfather, was born in 1882, also in Lincolnshire. He, too, was a gamekeeper though by 1907, he and his wife, Katherine, had moved south to Surrey, where he was employed at Marden Park, an estate owned by Sir Walpole Greenwell, one of the wealthiest stockbrokers in the country. Gustavus and his family were allowed to live in Marden Castle, a nineteenth-century gothic turreted folly that was built as a hunting lodge and sometimes used by Greenwell’s guests on shoot days. Gustavus began the Starmers’ connection with the region, which lasted for more than a century via Keir Starmer’s younger sister, also called Katherine. She remained in the area, close to where she and her siblings were brought up, until 2021.

During the First World War, Gustavus was a driver in the Army Service Corps. In 1917, he was found to be unfit for service because of heart disease. He was granted a gratuity of £35 and awarded the Silver War Badge, which was given to those who were honourably discharged due to wounds or illness. He died in April 1974, when Keir was eleven years old, and was still a resident of Surrey at that time. Gustavus’s son – and therefore Keir’s grandfather – was Herbert Starmer, known as Bert, who was born in 1905. Although he was born in Liverpool, he lived and worked in Surrey almost all his life. According to the 1939 Register, the national census compiled by the British government on the outbreak of the Second World War, he was an agricultural wheelwright based in the village of Woldingham. Later, in the 1960s, he worked there as a mechanic at a garage. His wife, Doris, who was Keir’s grandmother, was born in Surrey in 1907. The couple had four children – three boys and a girl. Their third son, Rodney, was Keir’s father. He was born in 1934 and grew up in Woldingham. Rodney was certainly born into a situation most people would accept as being ‘working class’. It is debatable, 3though, whether he can be described as having stayed in that social bracket throughout his life or whether, for reasons which will be shown, he managed to open a door through which his children could potentially make their way in order to live what would surely be thought of as a more middle-class existence.

Being overly critical of private individuals whom one has never met is never wise, particularly if, like Rodney Starmer, they are no longer alive to explain themselves. With that said, when researching this book it has been noticeable that he was not considered by every interviewee who encountered him to be an easy man to know. On a visit in late 2020 to the street on the outskirts of Oxted in which he lived from 1963 until his death in 2018, for example, those neighbours who felt qualified to discuss his personality agreed to do so on an ‘off the record’ basis only. The reason for their polite reticence was soon clear. Speaking of an often scruffily dressed man, who wore a pair of shorts and a T-shirt on most days of the year and who sported an almost Victorian-era beard for much of his adult life, they variously described him as ‘eccentric’ and ‘a bit of a strange character’. One neighbour said, ‘The Starmers were staunchly Labour, and many others round here were Conservative. At election times their house would be plastered with Labour posters.’ When asked if a clash of political views might have influenced their attitude to Rodney Starmer, they insisted this was not the case. With some reluctance, one of them added, ‘He was just not very nice.’

An acquaintance of Rodney’s also mentioned that he could remember receiving a round robin Christmas letter from him in December 2014 which contained at least one barbed comment – something he thought rather incongruous given the context. In the letter, a copy of which this person was willing to share, Rodney did indeed refer bluntly at one point to ‘some of the residents in Oxted’, of whom he clearly disapproved. In what sounds rather 4like a battle cry from a class warfare activist, he wrote of these residents: ‘The posher the voice, the more vulgar they are.’ As sweeping generalisations go, this one does seem to be somewhat gratuitous and may be said to shed some light on his personality and opinions, which those who knew him have made clear were unmistakably left-wing. To what extent such views shaped the outlook of his children is an open question, but it has to be considered at the very least possible that his judgement might have rubbed off on an impressionable young mind. Andrew Cooper, a childhood friend of Starmer, says his recollection is that whenever Keir spoke of his father, ‘He was always described as quite strict.’ Another friend, Paul Vickers, has said:

Keir’s dad was a very powerful, almost slightly intimidating, figure, a very big man and was always very principled. He was probably what you might call somebody from the traditional Labour left. I’m pretty sure that’s where Keir picked up his first political insights: from his dad. His father … would always ask you, and ask Keir, questions which revolved around politics. He expected us to be interested in politics.

Tony Alston, a friend of Rodney’s who knew him through their shared interest in competitive cycling, also suggested that his was a slightly unusual personality. ‘[Rodney] was what one might call a character,’ Alston says. ‘He was one of those bluff but really kind-hearted people. He would turn up to a funeral wearing green plus twos and a baggy top. He was perfectly respectable; he was just unconventional.’ Alston knew him mainly through the long-established Southern Counties Cycling Union, of which Rodney, a cycling enthusiast throughout his life, was president for several years. He suggested that some people who were involved 5in organising and running cycling events avoided getting on the wrong side of Rodney.

I never argued with [Rodney] because I don’t argue with people, but, if he had a view, he wanted it his way. Certainly, he would fight his corner, but not in an unpleasant way as far as I remember. He was certainly popular in his own club, but he could be a trifle awkward if he thought he was right and you were wrong.

In view of the mixed feelings which Rodney Starmer seems to have generated among some of his friends and acquaintances, perhaps it is fairest to rely for a character reference on the man who spent more time with him than all those quoted: his eldest son. When he was interviewed on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in November 2020, Keir Starmer said: ‘I don’t often talk about my dad. He was a difficult man, a complicated man. He kept himself to himself. He didn’t particularly like to socialise so wouldn’t really go out very much, but he was incredibly hardworking.’ He added: ‘I understood who he was and what he was, but we weren’t close.’

By contrast, his mother, Josephine, seems to have been far more popular. Those same neighbours who were so reluctant to talk openly about Rodney Starmer described his wife in glowing terms as a kind and friendly woman who was always cheerful. They were quick to add that they believed all four of her children had inherited her good nature. She was born in Woldingham in July 1939, four months after her parents’ marriage and six weeks before the outbreak of war. Her father, Ronald Baker, who was also born in Surrey, was an electrical engineer. The 1939 Register records his profession as a driver and fitter for road passenger 6transport. The origins of her mother, Marjorie, are less clear, though it appears she died in Croydon, Surrey, in 1959. Looking back to the beginning of the nineteenth century, Josephine’s forebears were employed in a wide range of jobs every bit as humble as those done by the Starmers. Records show that among her ancestors was an attendant in a Surrey County Council lunatic asylum, a printer, a miller, a general labourer, a servant and a laundress.

Josephine’s path through life was far from straightforward. By the time she was ten years old, a recurring pain in her joints caused her parents to seek medical advice. Eventually, she was sent to Guy’s Hospital in London for tests. There, aged eleven, she was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, also known as Still’s disease; so called because the condition was first described by the English paediatrician George Still in 1896. This rare illness, the cause of which remains unknown, is characterised by fever and rashes as well as joint pain, and it can have a profoundly destabilising effect on those who live with it. The symptoms and frequency of episodes vary between individuals and are hard to predict. Sadly, Josephine was not spared the worst of what the disease is capable of inflicting.

According to the eulogy given at her funeral in 2015, she was quickly taken under the wing of the consultant who was in charge of her, Dr Kenneth Maclean. As Josephine was facing the prospect of being confined to a wheelchair for the rest of her life, Maclean was granted permission by her parents to, in effect, experiment on her with the new steroid cortisone. It had never been administered to children before the 1950s, but it had been shown to reduce swelling in the joints of adults suffering with rheumatism. In Josephine’s case, it proved something of a wonder drug, enabling her to live a fuller life for much longer than might 7otherwise have been the case, albeit with consequences for her physical health as she entered middle age and beyond.

Josephine had to spend a considerable amount of time in hospital during her childhood, but that fact did not prevent her from passing the entrance exam to Whyteleafe County Grammar School for Girls in Surrey. It was while she was a pupil there, aged sixteen, that she first met Rodney Starmer, at a local dinner and dance being held by the cycling club of which he was a member. They struck up a close friendship immediately, despite a five-year age gap. By then, he had left Purley County Grammar School, had completed two years’ national service with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers and was apprenticed to a local toolmaking firm. After Josephine left school, she became a student nurse at Guy’s Hospital, allowing her to maintain her contact with Dr Maclean, whose pioneering treatment improved her quality of life so markedly and guaranteed that she remained able to walk. Her friendship with this highly respected doctor had one further, significant benefit. When she and Rodney married in the late summer of 1960, he was a guest at their wedding. According to Rodney, who delivered the aforementioned eulogy, he took the couple aside at their reception and told them quietly that if they intended to start a family, the unknown side effects on Josephine of the cortisone treatment meant they should not wait. He also promised Josephine that if she ever had any children, he would arrange personally for her to give birth to them at Guy’s.

In a demonstration of how robust Josephine remained as a young woman, she and Rodney took their honeymoon in the Lake District. There, Rodney wanted to share with his new bride his passion for climbing hills and mountains – an activity he had first enjoyed a few years previously when visiting the Dolomites in northern Italy. They stayed at the Dower House guesthouse in 8the grounds of Wray Castle on the western side of Lake Windermere and, not yet owning a car, made their way around the area by bus. Halfway through the holiday, and having already climbed eight mountains, they got into difficulties on Loughrigg Fell, a situation that was exacerbated by Josephine’s lack of stamina compared to her husband. By chance, they soon came across a pipe-smoking middle-aged man who was sitting on a rock with a sketching pad. Showing some concern, he asked if they were all right and, noting Josephine’s obvious exhaustion, advised them on the best way to descend the great hill.

The following day, they explained to Barbara Smith, the landlady of their guesthouse, the circumstances of this brief meeting. She told them that the man who had helped them was almost certainly her friend Alfred Wainwright. He was already reasonably well known by then in Britain as a fellwalker, author and illustrator, but he would go on to become a television personality who sold millions of books, many of which are still in print today. The best known of these is A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells, a seven-volume series detailing the hills and peaks of the Lake District, which is still regarded by many walkers as the definitive guide to the Lakeland mountains. Mrs Smith arranged for the Starmers to see Wainwright again the following year when they returned to the area. They got on well, and this resulted in a friendship which lasted for the next thirty years, until Wainwright’s death in 1991. The Starmers also remained on good terms with Wainwright’s second wife, Betty, until she died in 2008.

Rodney Starmer believed that Wainwright – who, not unlike himself, had a reputation as a rather gruff man of few words – acted as a crucial beacon of hope to Josephine over those three decades. He was always kind to her and concerned about her condition, and he would write to her when her illness flared up and left her bedbound or, as was often the case, in hospital. He 9is also said to have inspired her to continue climbing as many of the Lake District’s fells as she could by ending his letters to her with the words ‘Get well, the hills are waiting for you.’ Such was the respect the Starmers accorded Wainwright that Rodney confessed in Encounters with Wainwright, a book of tributes which was published by the Wainwright Society in 2016, that he and Josephine ‘shed a tear’ when they read his obituary in The Guardian. He also declared that both of them ‘loved him like a father’.

It is clear that Cumbria itself became equally important in the lives of Rodney and Josephine Starmer, for they visited there at least once a year throughout their marriage until 2014, the year before Josephine’s death. Despite her increasing incapacity, the couple managed to ‘claim’, or scale, 212 of the 214 Wainwright fells – an achievement which gave them much joy. This impressive statistic also features in Encounters with Wainwright, which, furthermore, includes a list of the health problems that dogged Josephine as the years passed by. They included her twice needing new knee and hip joints; her contraction of the MRSA superbug in hospital in 2000; and, finally, a fall in 2008 which broke a femur and resulted in her having a leg amputated just above the knee. In fact, this fall occurred while they were in the Lake District and required them to be driven by ambulance from there to London, where the operation was performed. Remarkably, thanks to Rodney’s engineering ingenuity, even after the partial loss of a limb and when Josephine was confined to a titanium wheelchair, they continued to climb to heights of more than 2,000ft. The modifications Rodney made to the chair meant it could cope with the terrain. He also designed a walking frame for his wife.

Rodney and Josephine took seriously the advice offered to them in 1960 by Dr Maclean about having children as early as possible. Having married, Rodney took a job as a works manager at a large toolmaking firm at Ashford in Kent. In a sure sign 10that they were keen to upend their own working-class roots, the young couple secured a mortgage which allowed them to buy a bungalow on the edge of Romney Marsh. In June 1961, Josephine gave birth to their eldest child, Anna. On 2 September 1962, Keir was born. It has become standard practice in media reports to state as fact that he was named after Keir Hardie, a founder of the Labour Party and its first parliamentary leader, yet Starmer admitted in one interview in 2015 that he had no evidence for this because he had never discussed it with his parents. Still, this idea has stuck, and he has never disabused anybody of it. Anna and Keir were followed in March 1964 by twins Nicholas and, thirty-two minutes later, Katherine. Thanks to Dr Maclean, all the siblings were born at Guy’s Hospital, despite the fact the family lived nowhere near the London Borough of Southwark, where it is situated. For any young woman in good health, the relentless nature of having to look after four young children who were born within three years of each other would be a challenge. That Josephine Starmer managed this task seems nothing short of extraordinary, particularly because her own mother was not alive to help her.

Shortly after Keir’s birth, the family settled at 23 Tanhouse Road, a three-bedroom semi-detached house close to the commuter town of Oxted, which sits at the foot of the North Downs. The house was built alongside a few dozen identical properties between 1928 and 1930. With barely more than 1,100sq. ft of floorspace and only one small bathroom, it would have been cramped for a family of six, particularly as the children grew older. A two-plate Aga in the kitchen was perhaps the only outward sign of what might be thought of as anything approaching domestic luxury. The house had a driveway at the front, on which was eventually parked the family’s Ford Cortina, and a back garden overlooking several acres of undeveloped land, meaning it was 11in an open and bright position. Today, Tanhouse Road is a reasonably busy thoroughfare, but its semi-rural location means it remains pleasant. Horses graze in the surrounding fields and a brook flows yards from what would have been the Starmers’ front door. In the 1960s and 1970s, when there were fewer cars on Britain’s roads, it must have been a relatively peaceful place in which to live. As a young boy, Keir had other children to play with locally, too.

Diana Watson, who was the same age as Starmer, says she can remember visiting him at home as a little girl more than fifty years ago. ‘I went to Keir’s house for a birthday party or something,’ she says.

Their house was very modest. Even though Surrey is traditionally quite affluent, they came from a very modest background. Surrey is thought of as being very much part of the Stockbroker Belt, but east Surrey is really quite rural. It’s near the Kent border. The Starmers were unpretentious. They were normal people.

She adds:

I remember his mother had curly brown hair and brown eyes, and I’m sure I remember noticing her hands were mis-shapen and asking my mother what was wrong with them, and she told me Mrs Starmer had arthritis. She had very kind eyes. I think they were quite like Keir’s in a way.

Paul Vickers recalled visiting the house when Starmer was in his teens and found it to be slightly chaotic but friendly: ‘I used to love going there. It was always like a building site and there were holes in the wall, there was bits of masonry missing. It was always 12as though they were trying to finish the house but never actually got quite around to completing the job.’

Having moved to Tanhouse Road in 1963, Rodney Starmer continued to work in the toolmaking trade, but, due to his eldest son’s ambiguous explanations, there has always been a certain amount of confusion as to his employment status. This uncertainty justifies examining the complicated question of whether he could objectively be thought of as working class or whether he was in fact a member of the middle classes. In March 2018, Starmer gave an interview to BBC presenter Nick Robinson, in which he discussed his father’s career. He said he ‘was a toolmaker working in a factory and working every hour, basically’. He added:

My dad was a toolmaker, he was a very good toolmaker, but he had to live through the policies of Margaret Thatcher, and that decimated manufacturing. I remember distinctly, he went out to work at eight o’clock in the morning, came back at six o’clock for his tea, and went back to work till ten o’clock at night.

The following year, he again talked about his father’s occupation, telling the BBC Radio 4 Today programme that he ‘worked in a factory’ as a toolmaker. And during a subsequent interview on Desert Island Discs, he returned to the pattern of his father’s working day, this time changing the hour that his father returned home after his first shift, saying:

He worked as a toolmaker on a factory floor all of his life, and my enduring memory as a child was him, as he did, go[ing] to work at eight o’clock in the morning. He came home at five o’clock for his tea, went back at six o’clock and worked through till ten o’clock at night, and that was five days a week.

13The inference that listeners to any of these broadcasts might have drawn is that Rodney Starmer was employed by somebody else, perhaps even in a lowly capacity, and may have been one of many toolmakers who toiled at a works. Yet this was not the case. For reasons best known to himself, Starmer did not use any of these opportunities to explain that his father in fact ran his own business, the Oxted Tool Company. Initially, he operated from a unit on a farm in the Hurst Green area, close to where he lived. When this premises was no longer available, he moved to a light industrial estate at Gaywood Farm in the village of Edenbridge, just over the nearby county border in Kent. Nicky Kerman, who still runs the site, says he can recall Rodney Starmer well because he was a ‘cheerful chap with a big beard’, who was one of the first people to rent a workshop there.

He was in Unit A, which is probably about 1,500sq. ft in all, and he almost always worked alone, to the best of my knowledge. He gave it up to look after his wife in the 1990s, as far as I’m aware. I think he specialised in making tools for other people. I remember he had a lot of machines and was clearly very good at his job.

No records of the Oxted Tool Company exist in the historical files of Companies House. This makes it difficult to assess how successful Rodney Starmer’s business became and indicates that he may have remained a sole trader – as opposed to running a limited company – throughout his working life. Keir Starmer did specify that money was tight when he was growing up, saying in 2019 that ‘there were many times when the electricity and the telephone bill didn’t get paid’. This suggests that the business may have struggled at times. It is thought that if he did ever employ other people, he did so only on a small scale or on an ad hoc 14basis. He was certainly more than an ordinary labourer, however. Indeed, his friend Tony Alston says Rodney Starmer told him he had once secured a piece of work from a government department. ‘Rodney was a precision engineer,’ says Alston.

At one time he was very left-wing. His company won a job working for the Ministry of Defence. I don’t know if it’s true, but he always used to say, ‘I rang them up and pointed out I was left-wing,’ and they said, ‘We know exactly what you’re like, Mr Starmer, and we’ve offered you the contract,’ so he took the contract.

Alston adds: ‘He used to do jobs that people couldn’t get done elsewhere. It was machine work, high-quality stuff. I’m under the impression that he employed other engineers from time to time.’

While it is fair to say that a person’s own sense of who they are and of the class they feel they belong to certainly matters, it is hard to accept that Rodney Starmer was a straight-up-and-down member of the working class, as his son has often suggested. This poses the important question of how Starmer regards himself. When, in December 2019, he hinted publicly that he was considering standing to succeed Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, he tackled this topic by telling the BBC Radio 4 Today programme:

And as for the sort of middle-class thrust, as you know, my dad worked in a factory, he was a toolmaker, and my mum was a nurse, and she contracted a very rare disease very early in her life that meant she was constantly in need of NHS care, so actually my background isn’t what [people] think it is.

Technically, everything he said on that occasion in relation to his father is true, of course. Yet as a skilled manual worker who 15was self-employed and who owned a house (with a mortgage), it is certainly arguable that Rodney Starmer would be thought of by some social scientists as being a cut above other toolmakers who did work in factories for other people. None of this would matter in any way, of course, but for the fact that Keir Starmer has not been totally explicit about it when asked, presumably for self-protective reasons.

Aside from their cycling and walking hobbies, Rodney Starmer and his wife enjoyed opera and classical music, and they would regularly attend plays and concerts all over Surrey, especially at the Barn Theatre in Oxted, which is known for amateur dramatics. Its chairman, Bruce Reed, describes them as ‘a lovely couple’ who would often attend the same musical two or three times because they enjoyed it so much. He says, ‘Rod would do anything for anyone. They were both salt of the earth.’ He also remembers that, in 2005, they posed happily for a photograph at the theatre with the Duke of Kent, the Queen’s first cousin, to mark the occasion when he opened a £300,000 extension containing a new wheelchair lift. In view of Rodney’s previously mentioned comments about a ‘posh voice’ being indicative of a ‘vulgar’ person, it is amusing to reflect on Reed’s account of the reverence Rodney showed the visiting royal. Reed adds: ‘Rod usually insisted on wearing shorts, apart from the one day that the Duke of Kent visited. He told me he’d been out and bought a pair of trousers especially for the occasion. He was a shorts and sandals and socks man throughout the year otherwise.’

Family holidays were always spent in the Lake District, though, perhaps oddly, the Starmers never took their children to meet Alfred Wainwright during these visits, fearing they would intrude on his privacy. Another of Josephine’s enthusiasms was keeping donkeys, and from the 1970s, they usually had at least two of these beasts living in their back garden. Rodney even became 16a director of the Donkey Breed Society, a national charity. They also offered a home to dogs that had been abandoned or needed to be rescued. All this was fitted in around Josephine’s thirst for knowledge and education. In the mid-1970s, she enrolled with the Open University and received a degree after three years of study. Religion is not thought to have played an especially prominent role in the lives of the Starmers, though Josephine is understood to have attended a local church into her eighties. Starmer has been open about being an atheist, telling one interviewer in April 2021 when asked if he believes in God: ‘This is going to sound odd, but I do believe in faith. I’ve a lot of time and respect for faith. I am not of faith; I don’t believe in God, but I can see the power of faith and the way it brings people together.’

As a result of Josephine’s illness and Rodney’s unsociable working hours, there were few adult visitors to the house during their son’s childhood. The family lived under the appalling shadow of Josephine suddenly having to be admitted to a high-dependency unit. Such was Rodney’s devotion to his wife that he stopped drinking alcohol so he would be able to accompany her to hospital at any hour of the day or night if need be. There, he would remain with her for as long as necessary, sleeping in a chair if it came to it. He became so well versed in her illness that he knew exactly what symptoms to watch out for and what combination of drugs she was to take depending on her state. Starmer has even recalled a time when he was aged thirteen or fourteen and his father rang him from a hospital to warn: ‘I don’t think your mum’s going to make it. Will you tell the others?’ Such unwanted and painful responsibility, placed on his shoulders at a young age, certainly forced him to grow up quickly and perhaps to take life more seriously than most of his peers. Inevitably, as shall become clear, it left its mark on his personality as well.

The four Starmer siblings were all sent to a primary school 17in the village of Merle Common, approximately four miles from Tanhouse Road. It was a small, Victorian building with only about fifty pupils and is described by Diana Watson, who lived next door to it and was an exact contemporary of Keir Starmer, as ‘rather sweet and idyllic’. It has long since closed. She says: ‘It was an old, purpose-built village school with an outside toilet block and a little village hall over the road where we would go for dancing and other activities.’ She says one abiding memory she has of this time is that Keir was ‘very protective’ of his younger brother, Nicholas, who was apparently prone to ‘making mischief’. Starmer has also discussed his brother in passing, once saying:

My brother struggled at school, whereas I did all right, and I remember my parents instilling in me that we were both as successful as each other and that you always measured what people were dealing with in front of them, and so they never singled me out as a golden boy. They were proud; they wanted me to do what I did; but they always brought it back to, ‘And your brother’s doing just as well in what he’s doing,’ so now I never use the word that someone is ‘thick’ or ‘stupid’ or not able to do things. I hate that language. Or that people are ‘bright’. I see it completely differently: that people are very good in different fields at what they do, and we measure them in that way.

Nicholas lived in the north of England and for some years worked as a mechanic. He died aged sixty in December 2024. Of his other siblings, Katherine is a careworker and Anna is believed to have worked in the NHS.

When they were aged eight, Starmer and his classmates moved to the newly built Holland Middle School nearby. Diana Watson joined him there and, like him, sat the 11-plus examination in order to determine whether, from September 1974, they would 18attend the local comprehensive school, Oxted County School, or one of Surrey’s grammar schools. Diana says that she has no memory of the school forcing them to work particularly hard in order to prepare for this rigorous test, perhaps because there was less competition for it at the time. In any case, she says, Starmer’s work ethic and attention to detail was already on show by then, in contrast to the vast majority of his classmates, suggesting that he did not need to be pushed. She says:

Holland Middle School was in a bigger catchment area, so there were kids from Hurst Green who went there as well. It was the feeder for Oxted County School, a comprehensive which at that time was less desirable than it is now. Keir was quite hardworking and serious. In our year, probably four or five pupils got into a grammar school. Keir was one of them; I was another.

There is no question that his passing the 11-plus was a source of great pride to his family, not least because his elder sister, Anna, did not go to a grammar school. Of the four Starmer siblings, Keir would be the only one to take this academic route through his senior school career. His parents decided that he would go to Reigate Grammar School, some twelve miles from their house – a distance long enough to require him to catch a bus every day. It is striking that it was on these bus journeys that he would forge some of his thoughts about politics, religion, justice and equality, therefore marking not just the beginning of the next phase of his life but also the birth of his belief system.

Having considered Keir Starmer’s background, perhaps it would be most accurate to say that it was neither ‘working class’ in the strictest sense nor ‘posh’, as some journalists have attempted to prove. Instead, it was closer to what marketing employees in 19the 1980s would have called C2 – a member of the skilled worker social class that was instrumental in returning Margaret Thatcher to Downing Street three times – and what some sociologists and academics in the more distant past would have termed petit bourgeois. This French term, akin to lower-middle-class, is one that would undoubtedly be well understood by Starmer, whose deep interest in Marxist theory was to fill hundreds of hours of his time as a young man.20

Chapter 2

Schoolboy socialist

When Keir Starmer entered Reigate Grammar School in September 1974, it was on the cusp of great change. Having been founded in 1675, it was one of the oldest and most traditional educational establishments in the country. Set in grounds close to the centre of the market town of Reigate, it was not a particularly grand place, but it did bear many of the characteristics of a public school. It was academically selective; it was open to boys only; it operated a house system; masters wore gowns; rugby took precedence over football; there was a thriving Combined Cadet Force; corporal punishment was standard practice; and a steady stream of alumni went to Oxbridge. Such outward projections of exclusivity might have appealed to a certain type of parent in Surrey, but, for a host of reasons, one would not have thought automatically that Rodney and Josephine Starmer would be among them. Not only did they support Labour, a party whose ideological opposition to such institutions was well known, but the school was in fact fee-paying for most of the time that their son was a pupil there – something many people in left-wing circles considered to be beyond the pale, even if they could afford to educate their child privately. In the past, Starmer has been accused of deliberately concealing his attendance at Reigate Grammar, so, given the level of public comment his apparent defensiveness over his secondary education has attracted, it is worth examining how this toolmaker’s son ended up 22at an independent school before considering the impact of this experience on his life and career.

One of the biggest political battles being fought during Starmer’s schooldays related to the very path on which his parents set him: the fairness of selective education in England and Wales. This vexed question had dominated British politics for decades. Rodney Starmer’s assumed political hero, Keir Hardie, had even spoken about the issue during the previous century. It was reported in the Westminster Gazette on 1 August 1896 that Hardie had attended an international conference of socialists, and he was quoted afterwards as saying that he believed everybody should receive a full education which was ‘free at all stages, open to everyone without any tests of prior attainment at any age – in effect, a comprehensive “broad highway” that all could travel’. Attitudes towards the 11-plus examination specifically and grammar schools in general had only intensified since the 1950s, and many radicals and progressives considered the entire system to be nothing short of immoral. A central charge was that grammar schools created a publicly funded elite whose members were destined for university, while those children who did not attend them had to make do with lesser expectations. All this was said by detractors to reinforce social divisions.

This was the backdrop to the decision in 1965 by Harold Wilson’s Labour government to instruct all 163 local authorities in England and Wales to close the 1,200 or so grammar schools which existed and replace them with non-selective comprehensive schools. Although this comprehensivisation process picked up speed during its first five years, its rhythm was interrupted in June 1970, after the Conservative Party won the general election. The new Prime Minister, Ted Heath, appointed Margaret Thatcher as his Secretary of State for Education and Science.

As the product of a grammar school herself, Thatcher believed 23in academic selection as the best way for bright children from poorer backgrounds to advance through life. Although she accepted the idea of non-selective education (she approved 3,286 comprehensives during the forty-four months she held the Education brief), she also wanted to protect good schools. In this vein, her first act as Education Secretary was to overturn Labour’s policy and issue what was known in her department as Circular 10/70. This directive meant that no education authority should be forced any longer to subscribe to the blanket policy of comprehensivisation. Education therefore became a matter of choice at a local level, potentially allowing some grammar schools to determine their own fate rather than having change thrust upon them. The importance of a common education for everybody may have been dear to many within the Labour Party, but Rodney Starmer was on Thatcher’s side of the argument when it came to the schooling of a member of his own family. He believed in having options rather than adhering to diktats.

The headmaster of Reigate Grammar School throughout Starmer’s seven years there was Howard Ballance. He had been in post since 1968 and was of a conservative frame of mind. He is widely remembered as a man who was devoted to his job. He was of the generation of schoolmasters which had served in the army during the Second World War, but that didn’t mean he was an authoritarian figure. For example, he made a point of memorising the Christian names of all 700 pupils in his care at a time when most teachers referred to boys by their surnames only. He was also aware that as the head of a county grammar school, he was responsible for boys from every social background, some of whom were less privileged than others. He would even liaise with the local police if a boy got into a scrape which might have led to him being charged with an offence, persuading officers to allow him to deal with the problem. He cared deeply about the ethos of his grammar school 24and the success of those in it. During his fourteen-year stewardship, the school prospered, with improved exam results, greater sporting success and more emphasis on drama, music and the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award. Most crucially of all, however, Ballance is credited with saving Reigate Grammar School from being incorporated into the comprehensive system and with setting it on a new course, of which Starmer was a direct beneficiary.

Reigate Grammar School was set up in the seventeenth century by Henry Smith, an alderman of London, when he bequeathed £150 towards the purchase of land for a ‘free school’. Later, it was linked to the local parish church of St Mary’s, until the mid-nineteenth century when it was reformed as an independent establishment. After this, it developed and expanded, leading to a Victorian building programme, the results of which still stand today. In the early twentieth century, the county began paying for able boys to attend the school as well, but by the time of Starmer’s arrival, it stood at a crossroads. Three decades earlier it had opted to be taken over by Surrey County Council under the terms of the 1944 Education Act. This meant it became a voluntary-controlled school. The school’s foundation owned most of its land and buildings and appointed some of the school governors, and the local authority funded the school and employed the staff.

Although Surrey County Council was dominated by the Conservatives, there was great enthusiasm among its reform-minded members for scrapping Reigate Grammar and creating a new comprehensive school and a new sixth form college in Reigate. When Ballance learned of this in March 1971, he took legal advice from a London law firm, Blyth Dutton, about how to break free of local authority control and, through Mrs Thatcher’s adjustment, revert to independent status. Two months later, on 23 May, the chairman of the school’s governors, Albert Channing Owens, wrote to Thatcher explaining that, following a vote, the governors 25wished to apply to discontinue as a voluntary-controlled school and become fee-paying. This request was made under Section 14 of the 1944 Education Act. The letter stated that the school had made financial arrangements with the Crusader Insurance Company Ltd, of Reigate, to buy from the local education authority any property and equipment not already owned by its foundation. Noting that it was bound to give two years’ notice to disentangle itself from the tentacles of Surrey’s education authority, it was also made clear that Reigate Grammar hoped to reopen as a fee-paying school in September 1973.

This move by a voluntary-controlled school was considered worthy of national attention. The Times picked up the story a few days later, quoting the chairman of the governors as saying:

We feel there is a great need in our part of Surrey for the sort of education we offer. There are 700 boys in the school, which is about the right number. The governors have agreed to the plan and now have been told that the teachers are 100 per cent behind it. Indeed there is absolutely no doubt that many would go elsewhere if we went comprehensive.

It seems highly unlikely that anybody in Surrey who took an interest in education would have been unaware that the future of Reigate Grammar was being fought over, and that, one way or another, it was on course to become a very different kind of school. Interested parties would almost certainly have included Rodney and Josephine Starmer, because their eldest son’s 11-plus exam was beginning to show on the horizon.

Surprisingly, more than two years passed before any meaningful response from Thatcher was forthcoming. Then, on 21 June 1973, a representative of hers in the Department for Education wrote to Owens to explain that the Secretary of State could not 26accept the application. The school was advised that a second application could be made but ‘only in association with proposals submitted by the local education authority under Section 13 relating to other maintained schools which would, if approved by [Thatcher], have the effect of leaving no place for the school in its present form’. The plans of Ballance and the governors were frustrated, forcing them back into talks with Surrey County Council.

Just over six months later, in February 1974, a snap general election was called by Ted Heath, which resulted in a hung parliament. Labour, still led by Harold Wilson, returned to government and Thatcher was replaced as the Secretary of State for Education by the Labour MP Reginald Prentice. By this point, Starmer had passed his 11-plus. Then, in June 1974, three months before he started at Reigate Grammar, the Surrey Mirror reported it was ‘almost certain’ that the school would become fee-paying after the council’s overtures had been met with ‘total rejection’ by the governors. By the time of Starmer’s first day in the school, Ballance was working six and a half days a week to secure the necessary funds to make it viable as a private institution.

David Jones taught languages at Reigate from September 1975 until July 2011. One of his first pupils was Starmer, to whom he gave French lessons. Jones says that Starmer’s first few terms would have been overshadowed by its unclear future but that many parents stepped in to help Ballance. ‘A very active, very accomplished parents’ committee was formed to promote and attain the independence of the school,’ Jones remembers. Their collective efforts paid off.

As Ballance negotiated a hefty loan with the local branch of Barclays Bank, teaching staff were promised a 5 per cent pay increase if they agreed to stay on at what he hoped would be the new fee-paying school. At the same time, provisions were made to take extra pupils – including girls in the sixth form – to 27increase revenue. Donations from wealthier parents were sought as well. Ballance’s second application to become independent, in line with Thatcher’s advice, was finally approved by Prentice in May 1975, at the end of Starmer’s first year. It was decided that the changeover would take place on 1 September 1976, the beginning of Starmer’s third academic year. Ballance became the first headmaster of a voluntary-controlled school in England to achieve the status of independence. Not only that but Surrey County Council eventually agreed to cover the cost of every pupil who had entered the school via the 11-plus for the duration of their stay – a figure which ran to more than £300,000 (about £2 million in 2024). Only the parents of new pupils arriving from September 1976 would have to pay.