5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

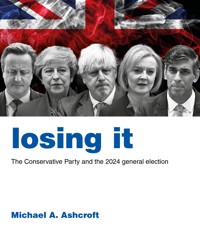

The 2024 general election produced the worst defeat in the Conservative Party's history. Five years after winning a commanding majority, the Tories lost half their vote and two thirds of their seats in parliament. In Losing It Michael Ashcroft examines the seismic result and its causes. Drawing on extensive polling and analysis – as well as conversations with voters across the country, who describe in their own words how the Tories squandered not just the election but their reputation for competent government – this is a pitiless account of how the Conservative Party came to be seen by those who elected it to office. Before the Tories can begin any kind of recovery, they need to understand and accept what happened and why. This book sets out the reasons in uncompromising terms.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 75

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

i

ii

losing it

The Conservative Party and the 2024 general election

Michael A. Ashcroft

Contents

vi

Introduction: Lessons from history

IT IS NEARLY TWENTY years since I published Smell the Coffee: A Wake-Up Call for the Conservative Party. That work, my first foray into political polling, aimed to show why the Tories kept losing elections. One of the most important findings was that, after eight years and two further defeats, they had still not really learned, let alone acted upon, the lessons that should have followed Labour’s landslide victory in 1997.

The Conservative Party cannot wait another eight years before getting to grips with what has just happened. On 4 July it lost half of its vote and two thirds of its seats in parliament. It is faced not just with an enormous Labour majority but, in Reform UK, an insurgent competitor on what it has always considered its own territory. Whether the Conservatives recover, and how quickly, will define the shape of politics for many years beyond the current parliament. The 2024 general election felt like a nadir, but there is no rule to say that things can only get better, as someone once said: there is no reason why there must be only two major parties or, if there are, why the Conservatives must always be one of them.

For the Tories to approach any kind of recovery, they will need to understand and accept why they lost not just the election but the reputation for competent government that was once an indispensable part of their appeal. To many readers, the reasons for viiithe defeat might seem so obvious as to be hardly worth writing down. But it is human nature, not least among politicians, to learn the lessons that suit you and draw the conclusions that fit with what you already thought. My large-scale polling and analysis, together with focus groups around the country with voters who switched to other parties, provide some pretty inescapable evidence of how the Conservative government came to be seen by those who elected it.

There are three broad reasons for what befell the Tories in 2024. First, it is always difficult for a government to be re-elected after so many years in office. The party gets tired and runs out of steam; disappointments accumulate; the voters grow weary and have a healthy instinct that it’s time for change.

Second, the Conservative voting coalition of 2019 was extremely unusual, and it was never going to be easy to hold it together. The combination of Jeremy Corbyn, Boris Johnson and the aftermath of the EU referendum threw together lifelong Labour voters, liberal remainers, Farage-supporting arch-Brexiteers and traditional Tories to produce a winning but unstable alliance with conflicting worldviews and contradictory demands.

But these are both reasons why winning yet another term would be tough for any government. They do not explain why the Tories got the trouncing of a lifetime: why people were so sick of them that the Liberal Democrats have taken the seats once held by David Cameron and Theresa May, or why we have Labour MPs in such socialist utopias as Poole, Bury St Edmunds and the Isle of Wight. For this we have to look to the third reason, which is that the Conservative administration became, to use a technical term from political science, a total shambles.

The Tories didn’t so much play a difficult hand badly as drop all their cards on the floor. People will understand and, to an extent, forgive the unenviable decisions that ixgo with running a country. Even now, many who abandoned the party still give former ministers generous leeway over their handling of covid, even on decisions they think look wrong in retrospect. What really did for the Conservatives was a series of unforced errors, both political and personal. In the last parliament, these began with partygate and continued right up to the election. They included a succession of unelected prime ministers, an experimental budget that produced the opposite of the economic stability that voters looked to the Tories to uphold, endless infighting, failure to keep promises, and a growing impression that the Conservatives were completely detached from their lives and concerns. To despairing voters, senior Tories seemed to be playing out a soap opera for their own amusement, rather than tackling the country’s mounting problems. The consequence was, among other things, a loss of trust in the party that voters say was the principal reason for its defeat and which will be extremely hard to repair.

Some argue that the Conservatives chose the wrong policy direction, and that correcting the course will be the key to its future. But in our conversations with former Tory “defectors”, the very few who thought this were as likely to say the party had become too right-wing as too left-wing (and even then, they usually thought its other flaws were more serious). The more common criticism of the government’s political direction was that it didn’t have one. Reminding the Republicans that they had to deliver for their voters, Ronald Reagan used to like to say, “you’ve got to dance with the one that brung ya”. But if you will permit another metaphor, it’s not as if the Conservatives took one group of voters to the party and then danced with another. It’s more that they went straight to the bar, got in a fight with their mates, tripped over their own feet and passed out in the car park. In the rain.

All of this is explored in detail in the pages that follow. Our participants complained at length about failure to control immigration, the cost of living, housing, the economy, xthe state of public services, and much more. But when we asked them to complete the sentence “By 2024, the Conservative Party had become too…”, the answers were more often about character than politics. “Broken”, “chaotic”, “clueless”, “complacent”, “confused”, “corrupt” and “crooked” only take us to the third letter of the alphabet (the rest can be found in chapter three) – and don’t forget, these are all from people who voted Tory in 2019.

It was not always like that. People like to talk about fourteen years of Tory failure, but the party faced three elections after 2010, won two with an overall majority, and achieved a bigger share of the vote each time. They were lucky in their opponents, but there was more to it than that. Many of our defectors, and not just to Labour and the Lib Dems, told us the best years of Conservative rule were the early ones. They recall in the Cameron era a sense of purpose, unity, stability, and absence of drama. Others were most drawn to Johnson, at least in the early days, enjoying his optimism and the sense that he understood them and was on their side. Some said that of the five post-2010 prime ministers they had most admired Theresa May, for her sense of duty and the calm way she got on with the job in seemingly impossible circumstances. For aspiring leaders, these are all qualities worth reflecting on.

We also asked people what, and whom, the Conservative Party had stood for at its best, whenever they thought that was. More often than not, the answer came down to stable, sensible government, a realistic understanding of the world, and people who worked and saved and tried to do the right thing. These things, they said, had somehow been lost along the way. Only one in ten defectors to other parties – and only just over half of those who actually voted Conservative in July – told us they thought the Tories were on the side of people like them.

Debate is already well advanced on what the party must do to recover. The phrase xi