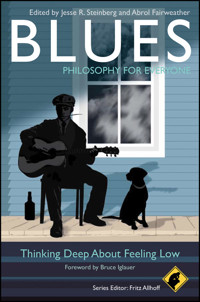

Blues - Philosophy for Everyone E-Book

18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Philosophy for Everyone

- Sprache: Englisch

The philosophy of the blues

From B.B. King to Billie Holiday, Blues music not only sounds good, but has an almost universal appeal in its reflection of the trials and tribulations of everyday life. Its ability to powerfully touch on a range of social and emotional issues is philosophically inspiring, and here, a diverse range of thinkers and musicians offer illuminating essays that make important connections between the human condition and the Blues that will appeal to music lovers and philosophers alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 444

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

FOREWORD

IT GOES A LITTLE SOMETHING LIKE THIS…

Part 1 – How Blue is Blue? The Metaphysics of the Blues

Part 2 – The Sky is Crying: Emotion, Upheaval, and the Blues

Part 3 – If it Weren’t for Bad Luck, I Wouldn’t Have No Luck at All: Blues and the Human Condition

Part 4 – The Blue Light was my Baby and the Red Light was my Mind: Race and Gender in the Blues

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Abrol Fairweather

PART 1 HOW BLUE IS BLUE? THE METAPHYSICS OF THE BLUES

CHAPTER 1 TALKIN’ TO MYSELF AGAIN

CHAPTER 2 RECLAIMING THE AURA

CHAPTER 3 TWELVE-BAR ZOMBIES

Playing the Blues

Defining the Blues

Wittgenstein to the Rescue

Good Blues, Bad Blues, Walking Dead Blues

CHAPTER 4 THE BLUES AS CULTURAL EXPRESSION

Two Categories of the Blues

What is Cultural Expression?

A Too-Loose Definition of Culture

Conclusion

PART 2 THE SKY IS CRYING: EMOTION, UPHEAVAL, AND THE BLUES

CHAPTER 5 THE ARTISTIC TRANSFORMATION OF TRAUMA, LOSS, AND ADVERSITY IN THE BLUES

The Roots of the Blues in Trauma, Loss, and Adversity

Transforming Trauma, Loss, and Adversity

The Blues as Living Oral History

Transformation through Music

Emotional Regulation in the Blues

The Creative Reverberation of Traumatic Loss

The Blues as a Living, Evolving Legacy

CHAPTER 6 SADNESS AS BEAUTY

The Nature of Beauty

Truth, Goodness, and Beauty

Beauty and the Blues

CHAPTER 7 ANGUISHED ART

CHAPTER 8 BLUES AND CATHARSIS

PART 3 IF IT WEREN’T FOR BAD LUCK, I WOULDN’T HAVE NO LUCK AT ALL: BLUES AND THE HUMAN CONDITION

CHAPTER 9 WHY CAN’T WE BE SATISFIED?

Introduction

Why the Blues will Always be With Us

Why Epictetus Never Sang the Blues

Akrasia, or ‘I can’t help myself’

Objections (‘This Life Sounds Horrible!’)

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction, and I Like it, I Like it, Yes I Do

In Place of a Conclusion

CHAPTER 10 DOUBT AND THE HUMAN CONDITION

How Does One Avoid Skepticism?

The Experience Machine

Contextualism

My Take on Skepticism

CHAPTER 11 BLUES AND EMOTIONAL TRAUMA

Emotional Trauma

The Therapeutic Power of the Blues

Three ‘Clinical’ Illustrations – The Role of Lyrics

Musical Characteristics of the Blues

Concluding Remarks

CHAPTER 12 SUFFERING, SPIRITUALITY, AND SENSUALITY

Marx Sings the Revolutionary Blues

Did the Buddha Have the Blues?

Kierkegaard’s Passion and the Passion of the Blues

CHAPTER 13 WORRYING THE LINE

Story

Song

Prayer

PART 4 THE BLUE LIGHT WAS MY BABY AND THE RED LIGHT WAS MY MIND: RELIGION AND GENDER IN THE BLUES

CHAPTER 14 LADY SINGS THE BLUES

Why so Blue?

Women and the Blues

Stealing the Blues

Conclusion

CHAPTER 15 EVEN WHITE FOLKS GET THE BLUES

CHAPTER 16 DISTRIBUTIVE HISTORY

The Rip-Off Account

Musical Traditions

Recorded Music: The Blues

Rock and Race

The Music Business

Sensibilities

The Evolution of Taste

Conclusion

CHAPTER 17 WHOSE BLUES?

Questioning Ourselves

A Twice-Told Tale

What Makes Us Different?

Whose Blues?

Our Blues

Unfinished Business

PHILOSOPHICAL BLUES SONGS

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

VOLUME EDITORS

JESSE R. STEINBERG is an assistant professor of philosophy and the director of the Environmental Studies Program at the University of Pittsburgh at Bradford. He has been a visiting professor at Victoria University in New Zealand, at the University of California at Riverside, and at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He has published a number of articles on topics including philosophy of mind, metaphysics, philosophy of religion, and ethics.

ABROL FAIRWEATHER is an instructor at San Francisco State University and the University of San Fransisco. He has published in the area of virtue epistemology and sustains interests in philosophy of mind, metaphysics, and philosophy of language. He has contributed to popular culture volumes on Facebook and Dexter. The guitar, vocals, and lyrics of Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mississippi John Hurt are major influences.

SERIES EDITOR

FRITZ ALLHOFF is an associate professor in the philosophy department at Western Michigan University, as well as a senior research fellow at the Australian National University’s Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics. In addition to editing the Philosophy for Everyone series, he is also the volume editor or co-editor for several titles, including Wine & Philosophy (Wiley-Blackwell, 2007), Whiskey & Philosophy (with Marcus P. Adams, Wiley, 2009), and Food & Philosophy (with Dave Monroe, Wiley-Blackwell, 2007). His academic research interests engage various facets of applied ethics, ethical theory, and the history and philosophy of science.

PHILOSOPHY FOR EVERYONE

Series editor: Fritz Allhoff

Not so much a subject matter, philosophy is a way of thinking. Thinking not just about the Big Questions, but about little ones too. This series invites everyone to ponder things they care about, big or small, significant, serious… or just curious.

Running & Philosophy: A Marathon for the MindEdited by Michael W. AustinWine & Philosophy: A Symposium on Thinking and DrinkingEdited by Fritz AllhoffFood & Philosophy: Eat, Think and Be MerryEdited by Fritz Allhoff and Dave MonroeBeer & Philosophy: The Unexamined Beer Isn’t Worth DrinkingEdited by Steven D. HalesWhiskey & Philosophy: A Small Batch of Spirited IdeasEdited by Fritz Allhoff and Marcus P. AdamsCollege Sex – Philosophy for Everyone: Philosophers With BenefitsEdited by Michael Bruce and Robert M. StewartCycling – Philosophy for Everyone: A Philosophical Tour de ForceEdited by Jesús Ilundáin-Agurruza and Michael W. AustinClimbing – Philosophy for Everyone: Because It’s ThereEdited by Stephen E. SchmidHunting – Philosophy for Everyone: In Search of the Wild LifeEdited by Nathan KowalskyChristmas – Philosophy for Everyone: Better Than a Lump of CoalEdited by Scott C. LoweCannabis – Philosophy for Everyone: What Were We Just Talking About?Edited by Dale JacquettePorn – Philosophy for Everyone: How to Think With KinkEdited by Dave MonroeSerial Killers – Philosophy for Everyone: Being and KillingEdited by S. WallerDating – Philosophy for Everyone: Flirting With Big IdeasEdited by Kristie Miller and Marlene ClarkGardening – Philosophy for Everyone: Cultivating WisdomEdited by Dan O’BrienMotherhood – Philosophy for Everyone: The Birth of WisdomEdited by Sheila LintottFatherhood – Philosophy for Everyone: The Dao of DaddyEdited by Lon S. Nease and Michael W. AustinCoffee – Philosophy for Everyone: Grounds for DebateEdited by Scott F. Parker and Michael W. AustinFashion – Philosophy for Everyone: Thinking with StyleEdited by Jessica Wolfendale and Jeanette KennettYoga – Philosophy for Everyone: Bending Mind and BodyEdited by Liz Stillwaggon SwanBlues – Philosophy for Everyone: Thinking Deep About Feeling LowEdited by Jesse R. Steinberg and Abrol Fairweather

Forthcoming books in the series:

Sailing – Philosophy for Everyone: A Place of Perpetual UndulationEdited by Patrick GooldTattoos – Philosophy for Everyone: I Ink, Therefore I AmEdited by Rob Arp

This edition first published 2012© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd., The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Jesse R. Steinberg and Abrol Fairweather to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Blues – philosophy for everyone : thinking deep about feeling low / edited byJesse R. Steinberg and Abrol Fairweather.p. cm. – (Philosophy for everyone)

ISBN 978-0-470-65680-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)1. Blues (Music)–Social aspects. 2. Music and philosophy. I. Steinberg, Jesse R.II. Fairweather, Abrol.ML3521.B64 2012781.64301–dc23

2011026137

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is published in the following electronic formats: ePDFs 9781118153253; Wiley Online Library 9781118153284; ePub 9781118153260; Mobi 9781118153277

This book is dedicated to the folks that have produced the greatestmusic on Earth. Thank you!

BRUCE IGLAUER

FOREWORD

The blues is an art of ambiguity, an assertion of the irrepressibly human over all circumstances, whether created by others, or by one’s own human failing.

(Ralph Ellison)1

The blues is a form of magic. Yes, magic, not just music. It is incredibly simple, usually involving somewhere between one and five chords; usually in 4/4 time; with verses rarely more than sixteen bars long; and often with only two lines of words, often one repeated, in a verse. Yet the blues is infused with a subtlety and power of emotion that transcend even the listener’s ability to understand the meaning of the words. The passion, the humor, the sorrow, the joy all seem to communicate on a subliminal, non-intellectual level that defies explanation.

Amazingly, the blues, a music that has won a worldwide audience, was created by an incredibly isolated group of people, an almost-invisible and often despised minority population with little interaction with the white majority in their unchosen home country. They were dragged in chains from their homes in Africa and deposited in a strange land under the control of owners who often literally worked them to death, enforced illiteracy, divided their families and original tribes, and often even banned them from owning musical instruments. Even after the legal end of slavery, the sharecropping system made it virtually impossible for African-Americans to emerge from dire poverty, to own land, or to create a future for their children. In their own country, they were (and still often are) the ultimate ‘other.’ All this in the ‘land of the free.’

How did these isolated, oppressed, often illiterate people manage to create a music that has reached beyond their own culture to find an audience among not only the white majority in the United States but also among people around the world? What is it about this music that can inspire fans and musicians in Argentina, China, India, Russia, and Singapore to adopt the blues as their favorite music? What is it about the blues that has fueled mainstream rock and pop music? And what is the ‘inside’ of the blues, the part that audiences have such a hard time understanding, even when they can identify and enjoy the structures and sounds of the ‘outside’ of blues?

For almost 300 years, African-Americans’ choices for brief relief from endless work and poverty were found either on Saturday night or Sunday morning. If they chose the church (the religion of their captors, which they transformed into something very much their own), then the ultimate brighter future was found after death, in the arms of Jesus, as so often expressed in song. If they chose Saturday night in the country juke joint or city blues bar, then the songs were secular and spoke, as does all blues, in literal terms about everyday life. Often these songs were of the disappointments of living, especially the failure of love to survive, either because of the cruelty of the beloved or the foibles of the singer, and, by extension, the members of his or her audience: ‘It’s my own fault, babe, treat me the way you want to do’ (from ‘It’s My Own Fault’ by John Lee Hooker). Sometimes they were about the positive attributes of the singer and again, by extension, the members of his or her audience. These were the attributes to which poor people could relate – primarily that of being a good lover, which could be suggested by the blues artist’s singing and playing ability, or the audience members’ dancing ability. And sometimes the songs were nothing but a release, a rhythmic excuse to party, to forget the hopelessness of daily life and just whoop and holler and try as hard as possible to attract a sexual/romantic partner. But, under any circumstances, the songs and the spirit of the songs were about reality, not the glories of the life in heaven to come. No wonder the preachers declared that the blues was ‘the devil’s music.’ Not only did the blues imply that the here and now were more important than the afterlife, but also those who spent their meager income on Saturday night had nothing for the collection plate on Sunday morning!

The continuing power of the blues is rooted in how strongly the music and the creators of the music (by which I mean not only the blues musicians but also the culture that created and nurtured them) had to fight for an iota of joy and a sense of community in the face of overwhelming odds – to be someone and not ‘the other.’ Even now, when the conditions that created the blues, at least those specific to the rural South, have almost disappeared, the power of the music that those conditions engendered lives on. Imagine a prize fighter who has built himself up to a level of incredible strength for the fight of his life. Even if the fight happened years before, the power of those muscles is still there. Thus, the power of the blues lives on.

Explaining the emotional, spiritual effect of the blues is almost impossible. Even defining the blues is a challenge. But here’s what we can perhaps agree on: The blues is a folk music form that was created primarily by African-Americans, probably evolving out of unaccompanied work songs. It generally involves both singing and playing instruments. It often has twelve bars and three chords arranged in a I-IV-I-V-VI-I structure. It usually contains flatted thirds and sevenths, the so-called ‘blue notes.’ Its lyrics speak of secular rather than religious or spiritual matters, though it shares many structures and vocal techniques with gospel music. Most blues has a strong, danceable rhythmic pulse. (Note that the inclusion of the long, flashy guitar solo is something that mostly happened after white fans adopted the blues. For black people, the blues was always first about words and groove.)

Okay, so we now have a vague but functional historical and musical definition. But then there’s that other quality, the emotional/psychological one that’s generally called ‘tension and release.’ How does that work, the part that ‘hurts so good’? Some psychologists say that the chord movement from V to I is somehow soothing to people on an elemental level. But there is that same chord movement in plenty of other types of music that don’t create the tension and release of the blues.

Often tension is created in the blues by things happening late: The voice will start a verse a beat after the instruments begin it. If there is drummer, he or she will generally be playing the snare drum on the second and fourth beats of a 4/4 measure, but will create tension by not playing squarely on the beat but intentionally a nanosecond behind. Singers and instrumentalists will intentionally hit a note that is below the ‘correct’ pitch (if you were writing out the parts on sheet music) and bend their note or voice up to the correct pitch, creating tension by entering ‘wrong’ and release by finally being ‘right.’ The longer it takes to get to the ‘right’ pitch, the more the tension and the greater the release. Listen to Albert King’s guitar or Muddy Waters’ slide to hear this technique done to perfection. These techniques are almost unknown in European classical music. They are all about Africa, where moving pitches are considered very much ‘correct.’ All these things speak to how the blues creates musical tension and release. But still, this doesn’t speak to how the blues works on us – that ‘healing feeling.’ That’s the eternal, wonderful magic of this music.

The blues certainly wasn’t created as a self-conscious ‘art form’ and most blues musicians, past and present, would describe themselves as entertainers, not ‘artists.’ The blues existed for decades as folk music, passed from person to person, before it was first recorded in 1921. But, in the country juke joints of Mississippi or the South and West Side black clubs of Chicago where I first got my blues education, the idea of discussing, dissecting, and analyzing the blues would have been laughed at. It was party and dance music, music for people who had literally picked cotton until their hands were raw or chopped animal carcasses in a slaughterhouse or cleaned houses (as Koko Taylor told me, ‘I spent many hours on my knees, and I wasn’t praying … I was scrubbing rich folks’ floors’ – from the blues standard ‘Five Long Years,’ originally cut and recorded by Eddie Boyd) or worked in a mill, ‘trucking steel like a slave.’ It was music to celebrate their mutual roots, to hear someone else singing the story of their lives, their loves, and their losses, so they didn’t feel so alone in their struggles. These people had almost everything in common. When I spent a Sunday afternoon at Florence’s Lounge on Chicago’s South Side, listening to Hound Dog Taylor, I was one of the few people in the bar who hadn’t been born in the South, who hadn’t labored in the blazing sun, who hadn’t come north with a few dollars in a pocket or purse, no education, and the hopes of finding a labor job and having a better life.

There’s a joke that says ‘all blues starts “woke up this morning.”’ Yes, that’s a cliché of the blues. But for the people at Florence’s this meant more than ‘I opened my eyes in bed as the sun came up.’ It meant that they were bonded by the mutual experience of ‘I woke up this morning knowing that in half an hour I’ll be pushing a massive plow behind a farting mule or bending over to hoe weeds, and I’ll be doing that until it’s too dark to see. And tomorrow and the next day and the next day, I’ll do it again, until, most likely, I work until I die, broke, just like my parents and grandparents.’ That was the shared subtext, the other information hiding in those simple lyrics.

As one essay in this book points out, the blues is no longer a popular music for most African-Americans. Even when I came to Chicago in 1970, when there were forty or fifty clubs in the black ghetto that regularly presented blues bands, younger blacks dismissed the blues as old-time, Southern music, and often used dismissive descriptions such as ‘Uncle Tom music’ or ‘slavery time music.’ Older blacks with roots in the South were often blues fans, but, even during the commercial heyday of the blues, from the 1920s through the early 1960s, many blacks preferred other forms of music, from jazz to gospel to vocal groups and even to white pop and country music. The blues was (and is) seen in the black community as blue collar music, music for the uneducated, the hard-drinking, the occasionally violent patrons of lower-class bars. The white parallel would be hillbilly music, the poor, moonshine-drinking, toothless, embarrassing cousin of commercial country music. Even though black people have defined the blues much more broadly than whites, and have included artists such as Dinah Washington, Louis Jordan, Sam Cooke, Johnnie Taylor, Otis Redding, and other black pop and soul singers under the mantle of the blues, blues was never the only popular music in the black community, and it has been decades since it was among the most popular. Meanwhile, audiences that know little of the culture that generated the blues have adopted and adapted the blues, morphing it into British blues and hard arena rock, and even injecting the structures of blues into punk rock.

Since the blues emerged from the Southern juke joints and Northern bars into the mainstream of American and world music, it has become more of a form of entertainment and less of a shared community folk music. When I sit in white blues clubs and primarily white festival audiences, rarely do I see fans stand up and holler, or wave their arms over their heads when the lyrics hit that familiar spot, the way the fans showed their appreciation in the black clubs. They may love the music but will generally wait until the end of the song to applaud or whistle their approval. The bluesmen and blueswomen present the music to the audience and the audience receives their presentation – the sharing of mutual experience isn’t there, even though the audience can still feel the tension and release. Does the blues work the same way on an audience of middle- and upper-class ‘blues cruisers’ as it did on an audience of black Southern sharecroppers or urban factory laborers? Of course not. But does that make its emotional impact less legitimate, or just different? Can audiences around the world, audiences that didn’t grow up in the blues culture, still feel the primal blues urge to survive the pain of real life by sharing it, and to glory in the joy of simply being alive, as the creators of the blues intended? I believe so.

With this book, we have a series of reflections, ruminations, and dissections of the blues as both a form of music and as a cultural force. Certainly these can give us some insight into the blues. But for a truer insight than any of these authors, myself included, can give, I urge you to dive into the very, very deep and endlessly invigorating well of blues music itself. Buy some blues recordings (I could suggest a good label if I weren’t so modest). Attend some live performances by blues artists, white or black, who have some sense of the tradition. Immerse yourself in this wonderful, invigorating, life-affirming music. It won’t hurt… or, if it does, it will be the kind of hurt that ‘hurts so good.’

NOTE

1 Ralph Ellison, ‘Remembering Jimmy,’ Saturday Review XLI (July 12, 1950), p. 37.

JESSE R. STEINBERG AND ABROL FAIRWEATHER

IT GOES A LITTLE SOMETHING LIKE THIS…

An Introduction to Blues – Philosophy for Everyone

The blues is deep. Philosophy is deep. Combined, they are doubly deep. However, you may be wondering whether these seemingly different enterprises really have any strong connection to one another. Is philosophy bluesy? Is the blues philosophical? A glance at the dominant figures in the history of each clearly reveals strikingly different colors – black and white, respectively. Moreover, blues and philosophy seem to focus on very different topics. Blues lyrics talk about women, whiskey, suffering, death, and the devil. The feel of the music is loose, gritty, raunchy, and rolling. Philosophy lacks a musical tone or tempo and avoids all mention of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll unless absolutely necessary. The feel of philosophy is tight, logical, and prim and proper. So the connection between blues and philosophy is not as apparent as that between Muddy Waters and McKinley Morganfield, or, as an example that philosophers are fond of, between Clark Kent and Superman. Blues and philosophy are definitely not one and the same. Yet the essays in this book make the case that there is a lot of connective tissue. These connections have to do with a shared approach and response to the many profound and enduring questions of human nature, knowledge, and existence.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!