Born Under a Union Flag E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A book about the relationship of a football club to a political decision? On one level this is madness. But in Scotland it makes perfect sense. What do Rangers mean to Scotland and what does Scotland mean to Rangers? What do Rangers mean to Britain and what does Britain mean to Rangers? How does the club and the game interact with the world around it? Questioning how British and Scottish identities fit into supporting Rangers, Born Under the Union Flag provides the first solid exploration of the relationship between sport and national identity. Well-known and informed contributors from both sides of the independence debate, including Harry Reid, Iain Duff, and Will McLeish, all lend their disparate viewpoints this book, showing just how nuanced - and difficult - the discussion really is. A must-read for anyone interested in Rangers, the history of Scottish football, or the independence debate. Like a great football match, when the final whistle is blown, the players will shake hands and move on. If they have any sense, the winners will be magnanimous in victory; the losers will rue the day but accept the result nonetheless. I guess the one thing neither side wants is a draw and a replay. But that's up to the voters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 308

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

COLIN ARMSTRONGis a former columnist for bothRangers Newsand the Rangers match-day programme. He contributed to the bookTen Days that Shook Rangers(Fort,2005) andFollow We Will: The Fall and Rise of Rangers(Luath Press,2013, and has written extensively on the subject of Rangers for other media, includingWhen Saturday Comes, The Rangers StandardandWATPMagazine. Born in Glasgow, he now lives in Falkirk with his wife Shona and their two children Connor & Sophie.

ALAN BISSETTis a novelist, playwright and performer. He was Glenfiddich Spirit of Scotland writer of the Year in2011and in2012was shortlisted for the Creative Scotland/Daily Record Writer of the Year award. His most recent novel,Pack Men,about a trip by Rangers fans to theUEFACup Final in Manchester, was called by Irvine Welsh ‘a landmark in Scottish fiction’ and was shortlisted for the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust Novel of the Year. He is active in the Yes Scotland campaign and is currently writing a play about Graeme Souness.

IAIN DUFFis an award-winning journalist with almost20years’ experience of writing for publications in both England and Scotland. He joined Glasgow’sEvening Timesas a news reporter in1995and two years later became the paper’s chief reporter at the age of25. The same year he won the prestigiousUKPress Gazette Scoop of the Year award and was nominated as Scotland’s young journalist of the year. He later joined the Press Association, where he was Scottish editor for six years. His books includeFollow on: Fifty Years of Rangers in Europe(Fort,2006) andTemple of Dreams: The Changing Face of Ibrox(DB,2008).

JOHN DC GOWis a freelance writer who is a regular contributor toESPNon Scottish football and RangersFC, and has contributed to football magazines such asAway End. He is also a co-founder ofThe Rangers Standard. Besides writing about football, he is particularly interested in studying Rangers and their relation to sectarianism, both in ending the backward form of hatred, but also how it relates to freedom of speech and belief.

ALASDAIR MCKILLOPis a co-founder ofThe Rangers Standard. He is the co-editor ofFollow We Will: The Fall and Rise of Rangers(Luath Press,2013) and a contributor toBigotry, Football and Scotland(Edinburgh University Press,2013). He is a regular contributor to the online current affairs magazineScottish Review, where he writes about sport and politics.

WILL MCLEISHwas born in Glasgow and spent more than ten years playing semi-professional football in Scotland. He is a formerBBCScotland sports broadcast journalist and was First Minister Alex Salmond’s political spokesperson from2007–2011(Special Adviser).

EILEEN REIDIs Head of Widening Participation at the Glasgow School of Art. She was formerly Lecturer in Philosophy and Politics at Langside College, and philosophy columnist with theGlasgow HeraldandScottish Review. As a columnist and in her current role she deals with a wide range of political, social and cultural issues, with particular emphasis on education, poverty and under-representation in Scotland’s institutions. She is also the eldest daughter of Jimmy Reid and works closely with researchers, biographers and others interested in her father, and working-class culture generally.

HARRY REIDIs a former editor ofThe Heraldand author of a number of books includingOutside Verdict: An Old Kirk in a New Scotland(Saint Andrew Press,2002) andThe Final Whistle: Scottish Football – The Best and Worst of Times(Birlinn,2005).He holds honorary doctorates from the Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow for his services to journalism.

GAIL RICHARDSONis a popular blogger and prominent member of the online Rangers community. A lifelong Rangers fan, she attended her first game at Ibrox when she was six years old. She is a socialist and a feminist.

JOHN ROBERTSONhas been Member of Parliament for Glasgow North West since2000. He worked for British Telecom for over30years, during which time he was active in the Communications Workers Union and West of Scotland chairman of Connect union. He is the chairman of the Westminster Rangers Supporters’ Club.

PAMELA THORNTONwas born and raised in Glasgow, then lived and worked in Gloucestershire for over25years. She returned to Scotland just as the new Scottish Parliament was born. Pamela’s father and uncle were Rangers supporters and she learned to sing ‘Follow Follow’ as a toddler. She is currently working on a novel. Pamela can be found on Twitter @pamelathornton.

ADAM TOMKINShas been a Professor of Law at the University of Glasgow since2003. He and two of his sons are season ticket holders at Ibrox. He blogs about Scottish politics at notesfromnorthbritain.wordpress.com.

GRAHAM WALKERhas published widely in the fields of Scottish and Irish history. He is co-editor with Ronnie Esplin ofIt’s Rangers For Me?(Fort,2007) andRangers: Triumphs, Troubles, Traditions(Fort,2010). He is the co-author, also with Ronnie Esplin, ofThe Official Biography of Rangers(Hachette Scotland,2011).

ALLAN WILSONis from Glasgow. His short story collectionWasted in Lovewas shortlisted for Scottish Book of the Year in2012. He is a founding member of Scotland WritersFCand is working on various novels, short stories and plays.

RICHARD WILSONis a Senior Broadcast Journalist atBBCScotland, having previously written forThe Heraldand theSunday Times Scotland. He lives, works and is immersed in football in Glasgow, a city that is also, captivatingly, full of contradictions.

ALEX WOODis a retired headteacher. He was born in1950, and spent his early years in Brechin, Girvan and Paisley. He writes on education for theTimes Educational SupplementScotlandand other journals. He is now completing a book on his experiences over four decades at the front line in Scottish schools. Throughout his life he has had an active interest in politics. He was a member of the Labour Party from1968until1986, was twice a parliamentary candidate and for seven years a councillor on Edinburgh District Council. For the last20years he has been a member of theSNP.

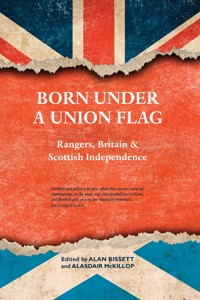

Born Under a Union Flag

Rangers, Britain and Scottish Independence

Edited byALAN BISSETTandALASDAIR MCKILLOP

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published2014

ISBN (PBK): 978-1-910021-12-5

ISBN (EBK): 978-1-910324-07-3

The authors’ right to be identified as authors of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988has been asserted.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Professor Adam Tomkins

Foreword by Richard Wilson

Introduction by Alan Bissett and Alasdair McKillop

1 A Hand-Wringer’s Tale

GAIL RICHARDSON

2 From Darlings to Pariahs: Rangers and Scottish National Pride

GRAHAM WALKER

3 Losing Your Soul and Discovering Your Roots

HARRY REID

4 The Man’s for Turning: How a Unionist Became Pro-Independence

COLIN ARMSTRONG

5 Constitutional Dilemmas: The British Club in Scotland

ALASDAIR McKILLOP

6 The Long Road From Ibrox to Brechin

ALEX WOOD

7 Two Rangers Fans Debate National Identity

ALAN BISSETT AND JOHN DC GOW

8 Bluenose Not Blue Noes

PAMELA THORNTON

9 Things Don’t Look So Different From South of the Border

IAIN DUFF

10 A Labour of Love

JOHN ROBERTSON

11 HMRC Miss the Target

WILL MCLEISH

12 A Tattoo of the St George’s Cross and Other Stories

ALLAN WILSON

13 Jimmy Reid’s Govan

EILEEN REID

Acknowledgements

DURING SEASON 2013/14, Rangers accumulated points quickly as the club strode to the League One title with ease. In putting together this book, we stockpiled debts at a similar rate. First, we must thank the contributors for producing a range of excellent chapters on a topic that didn’t necessarily lend itself to clear editorial guidance. They worked efficiently and dealt with requests with more patience than we as editors had a right to expect.

While it would not be proper to elevate any single chapter as being worthy of special praise, Colin Armstrong was in with the bricks, as it were. He helped knock the idea into shape and the project wouldn’t have come to fruition without his sound advice in the early stages. Elsewhere, Kirsten Innes and Rodge Glass looked over things from time to time.

Over the past couple of years, a number of people might have found themselves discussing aspects of the book without really knowing it. Thanks to Andrew Sanders, Ian S Wood, Peter Geoghegan and Tom Gallagher for a number of things, not the least being the production of work to inspire and aspire to. Encouragement and interest also go a long way. Gerry Braiden atThe Heraldregularly produces copy that will be a vital source for future historians interested in the places Scotland’s religious and political fault-lines meet. There have been plenty of stimulating discussions on these issues and more. For all things Rangers): Chris Graham, Stewart Franklin and Graham Campbell.

Gavin MacDougall, Louise Hutcheson and the staff at Luath Press directed the process with their usual expertise after greeting the proposal with support and suggestions.

Finally, during preparation of the book, Lucy Carol McKillop was born. A sense of much-needed perspective is the very least she offers. Her country might change around her and the fortunes of football clubs ebb and flow, but some things will always remain the same. This is for her, with love.

Foreword

PROFESSOR ADAM TOMKINS

A BOOK ABOUT the relationship of a football club to a political decision? On one level this is madness. But in Scotland it makes perfect sense.

It would not happen in England. If there were ever an English referendum on the break-up of Britain it would occur to no one to compile a collection of essays on what Manchester United, Arsenal or Nottingham Forest fans had to say about it. No club in England – of any size – has a political identity or a political presence similar to that which is enjoyed in Scotland by the two great clubs of Glasgow. But while Rangers and Celtic may be unique in Britain, there are comparators on the continent. Real Madrid and Barcelona are the obvious examples, and there are others in Italy. Likewise, the role played by Ajax in seeking to safeguard Dutch Jews from persecution at the hands of the Nazis has given the Amsterdam club an important political profile. I’ve been to the Amsterdam Arena only once but, as is sometimes also the case at Ibrox, the Israeli flag was flying high, proud and defiant.

I was born in England, raised and educated there, and moved to Glasgow 11 years ago. In England I was an Arsenal fan with a season ticket at Highbury. I rarely missed a home match and for years I travelled all over country and continent alike in support of the Gunners. I moved to Scotland for work. It was an opportunity that came knocking, not one that I had been seeking. While we were flat-hunting we stayed with a friend who was a colleague and a Bluenose. On the day we moved in to our new flat, Rangers hosted Arsenal in a pre-season friendly: the champions of Scotland against the champions of England. I bought tickets in the Main Stand and took my friend as a thank you for having put us up while we were in transition. Arsenal won 3-0, with a little help from the referee, as I recall. But there I was – at Ibrox – on the very first night of my new life as a resident of Glasgow.

Years were to elapse before I would return. With no dog in the Old Firm fight I declined to pick a side. During my time in London, Arsenal fans were divided over which of the great Scottish teams they should root for. Those who knew the club’s history tended to go for Rangers, but those who could remember only as far back as the 1970s were dazzled by Liam Brady’s midfield genius and knew that his association was with the green and white side of the city. So I sat on the fence and took myself to Firhill from time to time, pretending that I could somehow get used to a small club with a dreadful ground despite more than a decade of having been spoilt (in terms of ground and team) in London N5. I was kidding myself, but it was my oldest son who saw through it. Aged six, he was dutifully sitting next to me at Firhill and, bored in a quiet moment, starting singing, ‘We are the people!’ ‘Not here, we’re not,’ came his father’s swift reply, although when asked ‘Why?’ no explanation good enough for a six-year-old was forthcoming. On the way out of that game, which was dismal, my boy looked at me and said, ‘Dad, that was fun, but next time can we go to a proper match?’

I knew what he meant. His wee pal at school was a Rangers fan, as was his dad. And a week or two later the boys were sitting together in the Family Stand with their new Rangers scarves and grins as broad as you like. That was the week before the club went into administration. Undeterred, we bought season tickets in the Club Deck for the remainder of the season, went to the Old Firm game at which Celtic could have won the league (it finished 3-2 but all I remember is being 3-0 up) and, apart from moving our seats down the Main Stand for the following season, we’ve never looked back.

Watching the lower leagues through the eyes of my sons has been fun. If you’re only six or eight years old and your heroes are stuffing the opposition 8-0, it really doesn’t matter that it’s ‘only Stenhousemuir’. All that matters is that we score when we want, we’re top of the league, and we’re going up.

But I’d be lying if I said that I went along to Ibrox only in order to take my kids. It gives me a thrill to be the kind of dad that takes his boys to the game, but there’s much more to it than that. I absolutely love it. Being in a big crowd again. Belonging again. Singing again. Losing my mind with frustration again. I’d missed it, and it is wonderful to be back. I didn’t really choose Rangers just as a decade earlier I hadn’t chosen Glasgow. But when the chance came knocking, I opened the door and embraced it. Serendipity can be incredibly powerful, intoxicating even.

When, after the game, I return home a little hoarser and reflect on the day, I wonder why it is that this particular coat fits me so well. Why Rangers? Was it just luck? Or does it have anything to do with politics, with culture, with sensibility? It’s not a difficult question: of course it has to do with these things.

My 11 years in Scotland have changed me. Born and raised in England but with a young family settled in Glasgow, I’m no longer the Englishman I was. I’m British. And one of the reasons I love Rangers FC is that it seems to me to know how to be a British club in Scotland and a Scottish club in Britain. The club’s multiple identities reflect my own. But, more than that, they have helped me plant my feet more firmly in this city, no longer the Sassenach outsider looking in or passing through, but someone who has come to cherish Glasgow as his home.

Those of us who feel passionately about our Scottish or our British identities are engaged in a political argument that will define both Scotland and Britain for a generation or more. At Ibrox we see the Saltire and the Union flag flying side by side. Defiantly and proudly British and Scottish at one and the same time, what this says to me is that we don’t have to choose between them. We can be both. In this, I sense, all but the most extreme Nationalists and Unionists can agree. The argument is not ‘ScottishorBritish’, as if we can be only one of these things, but ‘how do we best realise our mixed and complex identities: together in Union or together simply as neighbours who share the same island?’

The Union flag, of course, represents not only the Union of England and Scotland but also the Union of Britain and Northern Ireland. One of the fascinating and most important facets of the Scottish independence debate is that the Irish question has (hitherto, at least) played no role in it. Whilst there is a close relationship between Ulster and West Central Scotland, both sides in the Scottish independence debate have sought to keep the politics of Northern Ireland distinct and firmly at arm’s length. The argument between Scottish Nationalists and Unionists does not map on to the much older, and much more bitter, dispute over the relation of Britain to Ireland. There is no evidence that Celtic supporters will voteen massefor independence: the longstanding ties between working-class Catholics and the Scottish Labour party have begun to loosen, but the SNP’s attempts to lure this demographic away from Labour have been only partially successful.

Likewise, as this book exemplifies, Rangers fans can be found on both sides of the independence argument. Indeed, some of the banners displayed in recent seasons by the Blue Order and the Green Brigade show that the two sides of the Old Firm have something in common: a shared sense of injustice at the SNP’s so-called anti-sectarian legislation, the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012 (whether the injustice is real or based on a misperception I leave for another day). Whether dislike of that legislation will influence the way supporters of the Old Firm vote in the independence referendum remains to be seen.

No sane person could want Scottish politics to become more like Northern Irish politics, but could it be too much to hope that the opposite may be true? Could something be learned in Ulster from the way we are doing our constitutional politics here in Scotland? Passions will run high in the independence debate. There is an awful lot at stake. But, like a great football match, when the final whistle is blown, the players will shake hands and move on. If they have any sense, the winners will be magnanimous in victory; the losers will rue the day but accept the result nonetheless. I guess the one thing neither side wants is a draw and a replay. But that’s up to the voters.

Foreword

RICHARD WILSON

FOOTBALL TENDS TO recoil whenever politics imposes itself. The game’s governing bodies, out of a sense of self-preservation but also to prevent a loosening of their control, actively discourage a crossover between the two. Clubs are supposed to exist in isolation from their surroundings, as though oblivious, but for some this is impossible, as well as unwelcome. Many sporting institutions owe their size, reach, status – even much of their glory and their despair – to the ties that bind them to a specific community. What, after all, would have become of Barcelona if the club was not a representation of the Catalan culture and identity?

In Scotland, Rangers and Celtic embrace their rich heritages, which are a potent combination of social, cultural and political influences as much as sporting prowess, while also trying to limit the extremist views that are potentially contained within these identities. They are precarious relationships at times, but then that is no reason to deny them. Football and politics do mix, often they are an essential combination, in the same way that football and culture, and football and society, are naturally entwined.

These connections ought to be properly understood, though. At this stage in Rangers’ long history, this subject is perhaps more interesting and more pertinent than it has ever been. A period of crisis reduced the relationship between the club and its supporters to one single dynamic: loyalty, for its own sake and for its ability to be nourishing and comforting. In the hour of need, fans responded out of a sense of duty, to be an essential part of the process of recovery. To not stand up for Rangers when the club was on its knees was to not be a true Rangers fan.

There was a cause, and it was to be there when the club needed you. The journey back to the top flight, to the former status and certainties, was a profound renewal of the elements, old and new, of the Rangers identity. But this has always been an ongoing process. It was, for instance, the 1970s when politically overt songs began to be heard from the majority of both sets of Old Firm fans. The Rangers support, too, was deeply influenced by the influx of shipyard workers from Northern Ireland during two migrations last century.

If the Rangers support could once be considered a loosely homogenous group, at least up to the early 1980s, that is no longer the case. What makes the fanbase so vibrant is that it spans across the social divisions of wealth, education and class. So ask one Rangers fan now what they consider to be their identity, at least in relation to the club, and their answer will differ from another Rangers fan, and another, and another. It is a defunct stereotype to pigeonhole the Ibrox support as mainly Conservative voting, actively Protestant, Unionist and Royalist. Complexities abound that enrich the notion of what it is to be a Rangers fan.

Yet at the same time, the celebration of Britishness – of a kinship with the rest of the United Kingdom, but most specifically England – has become more prominent in the past two decades. Rangers were once the national club of Scotland, with supporters organisations spread across the length and breadth of the country, and that remains broadly true. No team in Scotland would have prompted such a vast migration across the border as Rangers did when the team played in the 2008 UEFA Cup final in Manchester. Yet that essential Scottishness, which is most vividly reflected in the club’s heritage in the Govan shipyards and its deep, unbending roots in Glasgow’s working-class and professional communities, coincides amicably with a celebration of Rangers’ place in Britain.

If it remains the archetypal Scottish club, despite an ongoing wariness of the Scottish Football Association and by extension (sadly but hopefully briefly), the national team, then it is also classically British. Many football supporters in England take sides when it comes to the Old Firm, and they identify in Celtic the instincts of the underdog, of a rebellious nature, and in Rangers the sense of being the establishment. These are limited and unhelpful constructs in Scotland now, but still how the clubs are perceived in England and further afield. Outside Scotland, it is only in Northern Ireland and Ireland that regard for each team tends to strictly divide along religious lines.

Old Firm fans mostly celebrate their respective identities, because they are essential to their prominence. Without them, they would be two ordinary Scottish clubs, rather than emblems that the Scottish and Irish diaspora cling to across the globe.

At a time when Scotland is wrestling, intellectually and politically, with the prospect of independence, Rangers fans should eschew being limited by old ideas of what they represent. Books like this one provide a critical service. What does it mean to be a Rangers fan? What does it mean to be a football fan? How does the club and the game interact with the world around it? Supporters ought to be more self-aware, both to deepen the emotional ties with their club and to restrict the lurches into stereotyping.

Rangers fans are not defined by being anti-Catholic, or anti-Irish. Nor are they defined by being Unionist, despite the Union Jack flags and singing of ‘God Save the Queen’. Plenty of fans will, for instance, vote for independence. Politics remains an influence on the identity of the club and its followers, but only as one amongst several others. To be a Rangers fan is, at its most distilled, to celebrate the team and its history, the successes and the failures. It is to understand that Rangers as an institution once proudly stood for industry, endeavour, propriety, the pursuit and celebration of hard-won triumphs and of unashamed excellence and pre-eminence, and can do so again.

Discussions about football and politics, culture and society are more important than ever because the Ibrox support cannot be considered a homogenous group. It is mixed and divergent, full of contradictions, but bound to the same single premise: loyalty to the club, an emotional, financial and practical commitment to being part of the Rangers community, whatever your politics, your place in society, your background. Books like this one are important because it recognises, explores and asserts this diversity.

Football is, beautifully, both a simple and a complex sport. It is part of our everyday existence and so overlaps, enhances and contributes to every other aspect of our lives. We should embrace that.

Introduction

ALAN BISSETT andALASDAIR MCKILLOP

SCOTLAND IS CURRENTLY Undertaking a thorough examination of itself, intense even for a nation used to self-enquiry. The announcement of a referendum on independence from the UK, after the Scottish National Party’s majority win in the Holyrood elections of 2011, began a steadily growing focus on the sort of country we have been, are, and could be. Conclusions are multiple and contradictory – after all, where does Scottishness end and Britishness begin? – and also heavily contingent upon the as yet unknown result of the vote. ‘Stands Scotland where it did?’, as Shakespeare once wrote. Well, we shall soon see.

Sensing that constitutional upheaval may be on the way, the rest of the United Kingdom is starting to consider the implications. Chancellor George Osborne, for example, intervened recently to warn Scotland that the remainder of the UK would not be entering into a currency agreement, post-independence. In this, he was backed by the other Westminster parties. Such is the importance of the Union that the prospect of Scottish autonomy has been the sole political issue of recent times to bond Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats in unqualified common cause. One would likely have to go back to the Second World War to find such a precedent. Make of that what you will.

The term ‘rUK’ (meaning ‘rest’ or ‘rump’ of the UK) has been commonly used to describe a state that will carry on regardless, presumed to be a legally continuing entity from which Scotland has merely absented itself. However, it has also been posited that, given the UK was formed in 1707 by the union of Scottish and English parliaments (which built on the 1603 Union of the Crowns), both Scotland and ‘rUK’ will (or at least should) become new states, whose place in Europe will be subject to renegotiation and whose assets and liabilities would be contested. Such matters, touching as they do on history and identity, state and individual, have the potential to excite great controversy.

What any of this means for a unifying ‘British’ identity – as opposed to separate Scottish, Welsh, English or Northern Irish ones – is entirely up in the air. Some would argue that Scottish independence will cause a radical interruption, indeed ending of British identity; others, including Alex Salmond, claim there would be elements of continuity, based on shared geography, language, traditions, institutions and history. The social union is a concept that has been the subject of some debate and its expression following independence would surely be scrutinised intensely.

As this discussion has been taking place, Rangers FC, a 142-year-old club, has gone through one of the most traumatic periods in its history, following the corporate and footballing consequences of financial collapse in 2012. Rangers fans have in the past displayed banners describing their club as ‘quintessentially British’. How curious that ructions at this great institution – captive to successive robber barons and subject to a dismantling – have mimicked those of the nation-state from which the club draws its image. Pity the Rangers fan: facing Ayr United and Brechin City in the lower leagues, while Celtic sail unchallenged to domestic dominance and Scotland’s place in the Union is fiercely contested. Is it mere coincidence that Rangers first glimpsed their austere future in 2008, when Lloyds Banking Group demanded a tighter say on the club’s finances, the same year that the financial crash rocked world markets?

Indeed, over the last 30 years Rangers have served as a microcosm of the UK’s fortunes. The arrival of Graeme Souness at Ibrox in 1986, with the attendant wealth, glamour and success, mirrored an upsurge in the City of London after Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Big Bang’ deregulation of the financial sector. The ‘Nine-in-a-Row’ years in the ’90s, when Rangers dominated in both the footballing and business sense, tracked a UK economy buoyed by property, consumerism and retail. Rangers peaked with the high-spending Dick Advocaat boom of the early ’00s, just as the UK’s credit market reached immense proportions, before the chickens of reckless borrowing came home to roost and it became clear that the fiscal ambitions of both Rangers and the banks were not matching reality. For David Murray read Gordon Brown. For suffering Rangers fans read ordinary Brits.

Just as the rise of the SNP may prove to be a potential calling of time on Britain, so too did Scotland – at least, its various footballing tribes and organisations – turn a rancorous face towards Rangers at the club’s lowest ebb. There has also been the controversial shadow of an SNP policy targeted at Old Firm fans, for better or worse: the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications Act (Scotland) 2012. Some view this legislation as a well-meaning attempt to limit sectarianism, others a blow to freedom of speech.

While the rise and fall of the Light Blues in the last 30 years can be traced to economic and political patterns beyond the game, Rangers are, nonetheless, still a football club. Their symbolism can only be inferred and interpreted. It is true that Rangers FC make no attempts to hide their Britishness – a picture of the Queen, after all, hangs in the Ibrox dressing room – but they are also a Glaswegian entity, with strong historical links to the Govan shipyards, as prominent on the Scottish cultural landscape as whisky, golf or Billy Connolly. Indeed, this tension (reconciliation?) between Scottishness and Britishness in the form of Ibrox Stadium is one of the dominant themes of this book.

It is often taken for granted, by combatants on both sides of the independence debate, that a Rangers fan will or should be a dyed-in-the-wool Unionist, whose No vote is a foregone conclusion. No doubt there are many such Rangers fans. But there are also many who intend to vote Yes, just as there are supporters of Celtic, Aberdeen, Hibs, Dundee United and Hearts who intend to vote No. While no one would wish to portray Rangers supporters as paragons of virtue, lazy stereotypes can also surround the club. Are Rangers fans not as capable of free thought as their fellow Scots? Won’t the pragmatic and practical implications of independence or the Union win out over a loyalty to either flag? The mutual suspicion with which the Tartan Army and Rangers fans have viewed each other in recent decades may suggest some irreconcilable difference between overt displays of Scottishness and Britishness, but which Rangers fan does not cheer on Scotland? And which Scotland fan was not impressed by Danny Boyle’s spectacular opening ceremony at the London Olympics of 2012?

The overlap between Rangers and Scotland, or between Rangers and Britain, is the difficult terrain this book wishes to explore. Our line-up alone scotches (if you will) the idea that Rangers are a solely Unionist club: a number of our contributors are Yes-voting Bears who believe independence will bring about a better future for Scots. The fact that they couldn’t care less about the Union in no way diminishes their love for the team. Others in our line-up are pro-Union, and they have marshalled intellectual and moral arguments which defy the caricature of the knuckle-dragging Loyalist, an image which continues to be relied upon, even by those who should be rising above it.

We even have an Aberdeen fan reflecting on his conflicting feelings for the Glasgow club.

Each contributor brings a unique perspective on the independence issue, on national identity – whether Scottish or British – and on what Rangers FC represent. Personal histories are offered up as illustration, political narratives are questioned and tested. The stakes of this debate are high indeed and countless influences will determine where people stand in relation to the major issues.

For the record, our editors do not share a viewpoint on politics or Rangers. One of us is a Yes activist, the other a Unionist. One of us is a regular at Ibrox, the other has a connection based on nostalgia. One of us has written about Rangers through the lens of fiction, the other in a more journalistic capacity. Both of us have a desire to explore the complexity of this most inspiring, maddening and fascinating club, especially at such a significant crossroads in its own and Scotland’s history. In short, we wanted to ask: what do Rangers mean to Scotland and what does Scotland mean to Rangers? What do Rangers mean to Britain and what does Britain mean to Rangers? These essays are the results of that enquiry.

Sport is part of society and the idea that wider society is not affected by the reverberations from the coliseum is contested. As a ritualised form of combat, football can become a cauldron of symbols and themes. This year, the UK in general and Scotland in particular are going through a period of febrile, internal strife. As the referendum approaches, there’s the increasing feel of a nation being cleaved in two. Rangers fans are used to being one half of a binary division, just not this binary division.

What will emerge at the other side of the referendum – what kind of Scotland, Britain or Rangers – none of us yet know. But this book hopes to make a useful contribution to the most important national conversation in our recent, shared history.

1

A Hand-Wringer’s Tale

GAIL RICHARDSON

THERE IS A small group of Rangers fans whose motto is ‘Defending Our Traditions’ – a motto that manages to be both clearly defined and utterly bewildering at the same time. What are the traditions of Rangers? Beyond playing at Ibrox, wearing royal blue and winning a lot of trophies, I would struggle to come up with any. How can a sporting institution bear the burden of the views and ideologies of a diverse group of hundreds of thousands of people?

In season 2012/13, Rangers had an official average attendance of over 45,000 for home matches. When the team contested the 2008 UEFA Cup Final in Manchester against Zenit St Petersburg, it is estimated that over 200,000 Rangers fans travelled to the city for the event. How is it possible to accurately ascertain the views that these people hold, let alone expect a football club to represent them?

I would argue that many people simply project their own beliefs and values onto the club and expect it to uphold them. I would also argue that this is a form of madness.

What do you imagine when you think about a Rangers supporter? The answer to this is likely to vary, depending on your own allegiances. If you’re a Rangers fan, do you expect me to be like you? If you’re not a Rangers fan, do you have a preconceived idea of who I am or what I might believe? If you don’t imagine anything other than a red, white and blue scarf and a subway ticket to Ibrox, then you win a prize.

Of course, there is no such thing as a homogenised Rangers fan, but there are many stereotypes and misconceptions that are widely held about Rangers fans – by fans of opposing teams, the media and by other Rangers fans too. Most of these fall into the category of ‘isms’: Protestantism, loyalism, Unionism.