10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

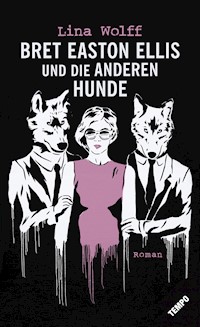

At a run-down brothel in Caudal, Spain, the prostitutes are collecting stray dogs. Each is named after a famous male writer: Dante, Chaucer, Bret Easton Ellis. When a john is cruel, the dogs are fed rotten meat. To the east, in Barcelona, an unflappable teenage girl is endeavouring to trace the peculiarities of her life back to one woman: Alba Cambó, writer of violent short stories, who left Caudal as a girl and never went back. Mordantly funny, dryly sensual, written with a staggering lightness of touch, the debut novel in English by Swedish sensation Lina Wolff is a black and Bolaño-esque take on the limitations of love in a dog-eat-dog world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 446

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

First published in English translation in 2016 by And Other Stories High Wycombe – Los Angeleswww.andotherstories.org

Copyright © Lina Wolff 2012

First published as Bret Easton Ellis och de andra hundarna in 2012 by Albert Bonniers Förlag English language translation copyright © Frank Perry 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or places is entirely coincidental.

Excerpts from “5 Dollars” from Play the Piano Drunk / Like a Percussion Instrument / Until the Fingers Begin to Bleed a Bit by Charles Bukowski. Copyright © 1970, 1973, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979 by Charles Bukowski. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

ISBN 9781908276643 eBook ISBN 9781908276650

Editor: Tara Tobler; Copy-editor and Proofreader: Sophie Lewis; Typesetting and eBook: Tetragon, London; Cover Design: Hannah Naughton

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s PEN Translates! programme. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

We gratefully acknowledge that the cost of this translation was defrayed by a subsidy from the Swedish Arts Council.

This book was also supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Contents

Not Everyone Gets to Choose How They Die, AlbaThe Proud Woman of PoitiersHeureux, comme avec une femme?meat is cut as roses are cutmen die as dogs dielove dies like dogs die,he said.

CHARLES BUKOWSKI ‘5 dollars’

Not Everyone Gets to Choose How They Die, Alba

‘It was Friday two weeks ago,’ Valentino told me on one of the days he drove me to school. ‘Alba Cambó and I met up at ten that morning and went for a spin in the car. They were playing Vivaldi on the radio. I had pushed the top back and it was a lovely day, the kind of day when the air smells of figs, salt water and sweet exhaust fumes. Alba was sitting in the same place you are now, her head against the neck-rest, looking up at the roofs as we drove through the streets and avenues. I recognised the music they were playing on the radio and hummed along to it while driving. I could never make love to Vivaldi, Alba said at that point. Vivaldi’s beautiful, don’t you think, I said. That’s why, she said. Imagine making love to the Gloria. Only saints can do that, and saints aren’t supposed to make love. Saints should be saintly. I thought about what it would be like to make love to Vivaldi. Maybe she was right. Maybe it wasn’t for people like us to make love to Vivaldi. It’s the sort of thing some people are able to do while others can’t. In any case it didn’t matter in the slightest at that moment. I had no intention of asking her to make love to Vivaldi. I was planning to ask her something else entirely. I was wondering how I should put it. I wanted to say something really big, something really important, only no matter how I tried to word it, it sounded banal. Since the first time I saw you. On the beach in San Remo. It sounded banal. San Remo sounded banal. It is a banal town, but that was where we met. Ever since I met you, Alba, it’s as though a bird has lodged itself in my heart and built a nest. It’s the bird of love. It’s you. That sounded banal as well, only then it struck me that the banal is sometimes what’s most true. I was going to tell the truth and even if the truth sounded banal, I was going to say it anyway. That was the price I was prepared to pay for telling the truth. I went over the different ways of putting it again and again. I kept thinking I’m going to turn towards her and say it now. But when I had finally mustered the courage, I saw she had fallen asleep.

We parked near Pla del Born. She woke up and we walked around on the lookout for a good restaurant. We kept walking, and it felt as though Vivaldi’s notes were dancing in my ears. Could you make love to this? I thought. Maybe if you were very old or very young. We sat at a bar and ordered drinks. We raised our glasses to each other and drank. The alcohol filled us up and made us happy. We started teasing each other. Then all of a sudden she put on a serious face and said: Valentino, do you want to marry me? And I couldn’t take it in. I really couldn’t take it in at all. This wasn’t how I had imagined it. It was meant to be my question. In my world, it’s the man who pops the question. In my world there are certain things the man has to ask and that’s not because I’m old-fashioned but because everything turns out better that way. Who wants a feminist woman in his bed? Who wants a feminist man in her bed? We should always endeavour to be someone else when we make love. That’s the only way out. She shouldn’t have said it, I thought, and Vivaldi kept dancing in my ears; something about the situation would go wrong now. You see, Alba, I said, I wasn’t expecting that. I really wasn’t expecting that. I’d imagined something different. I’d pictured something else entirely. I understand, she answered. You were the one who was supposed to say it. I got in before you. That’s right, I said. You look so sad, she said and reached up to stroke my cheek. Where’s the champagne? I thought.

We went walking round again, without a plan and without any pleasure either. We did not return to the question. We simply pretended it didn’t exist. We walked along little streets and there was ivy hanging here and there. We came to a dusty little shop selling old clothes and things. Let’s go in, said Alba. As we opened the door, the smell of mildew hit us. Pots, pedestals, busts, stuffed birds, a boar’s head and fabrics in bold colours were scattered about indiscriminately. Behind the counter was an old lady with grey hair in a bun who looked at us suspiciously as we moseyed around. Alba opened a cupboard and a pile of clothes slid out onto the floor. She started lifting up one garment after the other. She picked up an antique shawl and a small jacket with gold embroidery. What’s this? she asked the woman behind the counter. From the estate of someone who just died, she answered dryly. They only came in an hour ago and I haven’t had time to put them on hangers yet. They belonged to an old aficionado and his wife. She added the last bit reluctantly as though she didn’t consider us worthy of the information. She stepped behind a curtain and started fiddling with something and after a few seconds the sounds of Nisi Dominus issued from the loudspeakers. Alba looked up at me and smiled. Do you hear that? Yes, I said. So now we know what we’re not going to do, she said, and continued rooting through the pile of clothes. I just stood there. She asked me to come over. Put this on, she said, holding up the goldwork jacket. No, I said. I refuse to put on the clothes of someone who’s just died. If you want to try them on, you can change behind the curtain, said the lady. I don’t want to try them on, I replied. It felt as if drooping spiderwebs were entering my ears. There was itching all over my upper body. He died of a broken heart, the woman said. What a dull way to die, said Alba. Not everyone gets to choose how they die, the other woman replied. I just don’t understand what you can do with all this, I said. Everything is old and dusty. It feels unhygienic. These are lovely garments, the woman said then, and her eyes seemed to glitter in the half-light. Aha! Alba laughed. There speaks the mighty Thor, who kills bulls with his bare hands but is scared of a few fleas. And the old girl behind the counter laughed as well, and I could see she didn’t have any teeth. Her mouth was a black hole, a helter-skelter ride down to something that had no shape or form. That’s right, I said, the mighty Thor has spoken, and tried to laugh along with them. Alba was rummaging around behind the curtain. Then she drew it to one side and stood there wreathed in lace and with a hat on her head. She wasn’t wearing anything on top and you could see her breasts. Alba, I said. Put something on. Just give it a rest, she said. You really should cheer up. I could feel something touching my arm and jerked away before realising that it was the woman who had crept up beside me. The smell of old age seemed to waft from her and I moved a step further. So lovely, she said and her toothless mouth smiled broadly. That scarf was just lying there waiting for a woman like you. It was then I noticed that she was holding a silver tray in her hands with liqueur glasses containing something transparent. Do try it, she said and offered the tray to me. No thank you, I said. Go on, she said as her smile vanished. Just take it, Alba said, standing there in the black lace. Bloody old cow, I thought, draining the contents of the glass and then slamming it back down on the tray with a bang. Bloody old cow and her smelly dead-people-clothes. Come on Alba, let’s go, I said. Not until you’ve tried on the matador jacket and stood beside me for a photo, she replied. She crossed her arms and looked defiant. The old woman held out the tray to her and she took a glass. On one condition, I said then. That we leave afterwards. Immediately. Of course, said Alba. We shouldn’t spend too long in the air in here in any case. The other woman nodded and didn’t seem the slightest bit offended.

I took off my shirt and struggled into the gold jacket. The old lady’s hands wove across me like the fingers of a spiderwoman, fastening buttons and adjusting loops. Then she and Alba stood in front of me and looked me over with a critical eye. There’s something missing, the old woman said and went over to root through the pile. She returned with a cape that she swept across my shoulders. Then she removed a sword from an umbrella stand and put it under my arm. That’s it, she said. Let’s take the picture now. Alba handed her the camera and then came and stood next to me. Smile, she said. I tried out a tentative smile. The old woman took the picture. Alba got her camera back, and we looked at the image. I smiled when I saw us, despite the situation. And whenever I have looked at the picture since, I have noticed the assurance in my gaze, the indolent self-confidence in hers. Me as a matador and her as a prostitute. That was the way we were going to live. Full on, flat out and no teasing the brakes. Wholeheartedly. Otherwise why bother? We would live life even if it killed us. That was what we would do and that was the moment I realised it. Alba Cambó and I would live life, even if it killed us.

I struggled out of the coat and the jacket. Everything seemed to smell of elderly, mildewed man. Alba was still preening in front of the mirror. The old woman kept staring at her. Her mouth was half open, she had put down the tray and her arms hung loose along her sides. Come on, I said. Alba finally got changed while chatting with the other woman. The old lady was answering in hoarse monosyllables while peering intently at Alba. Thank you, this was fun, Alba said as we walked towards the door. Wait! the woman called. You must take the lace with you. You can have it, it belongs to you. Alba wound it around her throat and then shook hands with her. Then we stepped out onto the street and I could sense that the old woman was still standing there following us with her eyes, but I didn’t want to turn round.

Something had changed when we got out into the fresh air. We felt happier. It might have been the liqueur, maybe the oxygen, but all the gloom suddenly seemed to have been lifted. We walked back and forth along the streets. We went into a bar and had several drinks. We talked about music you could make love to. The Verve, said Alba. I don’t know who they are, I said. Nor do I, she said, only I’ve heard they’re good for that purpose. We laughed. We walked on. We went into a restaurant and ordered grilled prawns. Everything was perfect. It wasn’t too hot and it wasn’t too cold, the cava slipped beautifully down our throats. Alba was sitting there with the black lace around her throat, saying apparently unconnected things like: “I can’t understand why men are so fond of sex,” and “Once I saw a skull in the water when I was swimming off Palmarola,” and “When the main problem people have is that lack of lightness, it’s all over for them.” I just sat there nodding. Is that right, I would say. And I made no comment on her comments about sex. As for the skull, I told her I had seen a skull too, on Sardinia, only it wasn’t floating around but in the cliffs. I had swum a bit away from the shoreline and turned around which is when I saw it in the rock face. The black holes of its eyes were staring at me. So I know what you’re talking about, I said, you get this kind of tingling feeling in your toes when you’ve got a thousand cubic metres of water underneath you and you look towards land and see a skull. We continued in this vein, confused and drunk, and most of what we said was disconnected and meaningless but we were finally happy again and felt grateful for that.

The waiter was friendly and came over with our prawns. He put out bread, and all around us people were murmuring at the other tables but no one was loud or disturbing. I just can’t believe what a great time we’re having, I said and Alba nodded and stuffed a prawn into her mouth. So great we should feel guilty. You’re so right, I said. We groped one another under the table. We talked about going to the cinema just to be able to neck for a bit undisturbed. A bad film, at the very back of the stalls. We ordered elderberry sorbet and daiquiris. Alba took a joint out of her bag and smoked it, and the waiter didn’t seem to care. After a while I felt that the time was ripe to return to the question. So what about getting married? I said. We’ll get married in May, she said dreamily while blowing out smoke. We’ll marry in Albarracín in May. The poplar trees along the river will have just come into leaf. And the sun won’t have scorched the earth. Everything will be warm and expectant. We’ll be able to paddle down in the ravine and eat long dinners at open-air restaurants. We’ll be able to make love in the Castilian four-poster beds at a parador.

Although I’d never been in Albarracín, I could see it in my mind’s eye. A little village on a mountain. A ravine, poplars whose leaves twist in the wind and rustle softly. Black, heavy beds, black velvet, closed shutters, narrow strips of light that creep in during the hours of daylight. I could see it all before me and it was as though I had always been there, in Albarracín, as though I had always wandered the surrounding hills with the wind in my face, and the views. No lowlands. No tired cattle roving around. Just mighty birds hurling themselves into the air. Yes, we will, I said and my eyes filled with tears. Is it legal to be this happy? I laid my head on her shoulder. She stroked my cheek. They’ll be tossing us into the dungeons soon, she said. When you’re this happy, it can only ever be the last circle.

For a few hours I was convinced that I was, or at least could be, that happy. I looked out of the corner of my eyes at her walking by my side. I thought about the soft leather of her boots and the way it wrapped round her ankles, the tights that accompanied her body up to the navel. In my mind I traced every promontory and every valley along her. I could see before me how we would wake beside one another every morning from this moment on. As thrilled as it was envious, the world would look on. Time would stop as we passed by. I could see it all, and for a few hours I managed to forget completely the impossibility of the equation.

But at some point the day started to go downhill. I don’t know exactly when, but it was after we had paid and were just about to get up and go. It was then that the day fell flat with as much grace as a wounded crow. The energy drained out of me and Alba was slumped listlessly across the table. I even think the sun went behind a cloud. That was the good bit, Alba said. Don’t forget we’re getting married in Albarracín, I said. Don’t worry, I’m not going to forget that. But they mustn’t play Vivaldi. I tried to laugh and felt the wine fumes back up into my mouth. I got up and went to the toilet. It was filthy and someone had urinated beside the seat. I stood there and peed. I went back out to Alba again and she had got up and was standing there waiting, looking strained and reproachful, as though she was thinking where have you been all this time. We walked around. I looked at the clock and it was quarter to five. Which meant it was exactly four hours before the call from the hospital. How did we while away the hours? I don’t remember. I think we felt cold even though it was hot. I remember that we moved out of the shadows and into the sunlight and I remember that we moved once again when the sun was blocked by a building that cast a shadow over us. I think maybe the conversation faltered and that talking began to be a bit of an effort, that we started to feel we had to last it out. I think I even wondered when the day would ever end, when we could go home go to bed and put out the light.

When the call finally came, evening had fallen. We had eaten again, at a different restaurant and this time just soup and some fruit and a bottle of still mineral water. Her mobile rang. She looked at the display, got up and went out. I remember thinking: who is this person she can’t talk to in front of me? When we’ll soon be sharing everything? I could see her back from the table by the window. She was in the foyer and the waiters were moving round her carrying their trays. She was standing absolutely still. I fiddled with the ashtray and the toothpick container. The salt cellar had swollen rice grains in it. They looked like maggots. She came back, pulled out the chair in front of me and said, That was the hospital calling. They’ve got the results of my tests and it looks as though it’s malignant. What is? I said. The tumour, she answered. You never mentioned any tumour. Didn’t I? I thought I’d told you. Well, you hadn’t. Really, that’s odd. In any case it has spread and they think it’s too late to operate. I laughed, thinking it was all a joke. They don’t tell you things like that from the hospital. Not at night, not something like that over the phone. Not when two people are feeling so happy. Yes they do, said Alba. They didn’t want to tell me at first but then I lied and said I was abroad and wouldn’t be home for another four weeks. So then they told me. Her face looked as though it had been carved out of white stone. Her jaws moved slightly. Only, I said. Only. I didn’t know what to say. We were going to, I mean. Albarracín. The poplars and the ravine. Time was going to stand still. Albarracín. In my mind’s eye I could see a pair of cogs that had trapped a piece of flesh and were grinding it down. I tried to visualise something else. The future. The poplars. The leaves twisting in the light. The waiters walked past. One of them opened a window. The sounds from the square outside entered the restaurant. I could hear a man telling off a child, I could smell roasted chestnuts. A woman was laughing loudly. The church bells struck. I sat there thinking: the smell of chestnuts, a man telling off a child, the bells striking nine. This is how it is. It’s nine o’clock and there’s nothing to say I have to stop loving her.’

Not that Valentino’s story was the first I had heard of Alba Cambó. Our initial impression of her would be based almost entirely on what we read in the magazine Semejanzas. The same day she moved in below us (we realised that someone had come to stay because the broken pots and abandoned crowbar that had lain down there for as long as we could remember were suddenly gone and in their place were two individuals having a conversation while the aroma of exotic food found its way up to us), Mum went to the market to find out what was going on. No one knew anything at the market that afternoon apart from the fact that there had been a moving van in the street the day before, and that things had been unloaded and that a woman who must have been Alba Cambó had stood there keeping a watchful eye on the moving men as they handled her boxes. This was not enough for Mum, however, and she went down to the market again the next morning. A few hours later she came home with the latest issue of Semejanzas, which she had walked all the way up to Fnac near Pla Catalunya to buy. We leafed through the glossy pages. First there was a feature about a man who devoted himself to the illegal fishing of mussels in the estuary outside Vigo, followed by an interview with a prominent writer from Madrid whose name I can no longer remember but whose photo etched itself deeply into my brain because of a minor detail in the background: the muzzle of a pistol peering out from a bookshelf. Then there it was, the piece written by our new neighbour. A picture was included of a woman smiling and looking at someone outside the image, and there couldn’t be the slightest doubt it was her. Mum read her short story aloud. Nineteen pages long, it was about an extremely lonely man in the district of Poblenou. The man had no name in the short story but was referred to simply as ‘the man’. He was described as rather short with thinning hair and large, slightly staring eyes that looked enormously unhappy. The man’s problem was that he had been alone for so long that he had slowly but surely begun to develop a social phobia. Initially the phobia was nothing more than a vague reluctance to engage with other people, a reluctance that was manifested for the most part by his staying away from meetings with people he knew and regretfully declining invitations to family gatherings. But the problem rapidly developed into something else, something that could no longer be ignored and that imposed severe limitations on the way he lived his life. The clearest evidence that the man in the short story actually suffered from a phobia and not just from a common or garden aversion to the world around him was that he was no longer capable of eating without embarrassment in the company of other people. His hands shook so much that the food dropped off his fork and the fork would sometimes then fall out of his hands and onto the plate, landing with what sounded to him like a deafening clatter. His embarrassment was immediately evident in the colour of his face. Sometimes the man would even blush when there was not the slightest reason to do so, which meant that other people’s eyes were drawn to him, making both the situation and his phobia worse. His nearest and dearest were most concerned. Finally his daughter arranged a surprise party for him. His sixtieth birthday was coming up and his daughter thought this would be a good occasion to gather friends and family together. Perhaps a large social gathering might also alleviate some of her father’s phobia? She had heard that exposure to the objects that trigger phobias was always a positive thing. The daughter managed to get a group of about forty people together. They were all standing there in the dark in the hall of the man’s flat in Poblenou one evening as he made his way home from work. The man opened the door in the same slow and effortful way he always did. The forty people could hear the key being turned in the lock, the man putting down his briefcase on the floor in the hall and closing the door behind him. For a second or two there was absolute silence. You could have heard a pin drop in the darkness, the daughter would say a few pages later in the short story. All the guests held their breath while they waited for a signal from the daughter to burst into a chorus of congratulations, to the accompaniment of the light from the ceiling lamp which had been wreathed in coloured paper along with streamers and confetti that would be thrown up into the air to rain down over him. But just before the daughter could give them the green light, the socially phobic man farted. He was easing the pressure in his stomach, a pressure that had been building up throughout the day at the featureless office the man worked at, a pressure that Cambó described as a kind of internal and repressed rebellion against the beige-coloured walls and the white, rather damp faces that are typical of many fat people, people who never spend time in the open air, and people who eat nothing but sausage, if such people exist, that is. The sound that came out of the man was lengthy and sustained. It echoed between the walls and was drawn out into a kind of lamentation; it was then transformed into the cry that issues from the gullet of a bird one evening on some isolated mountain lake, and was finally followed by a sigh of relief. The daughter stood there paralysed in the darkness. The whole thing fell apart. The signal for the festivities to begin was not given despite the fact that the noises of celebration might have drowned out bodily sounds. A smell of sewage slowly spread through the hall. After several more seconds (Cambó managed to make the duration of these seconds appear to be an eternity) the daughter gave the go-ahead, and the guests began their gaudy congratulations. But the congratulations were only half-hearted. Derailed, embarrassed congratulations, congratulations characterised by shame, embarrassment and sorrow. Some ill-concealed giggling could also be heard from the youngest female members of the family. The eyes of the guests kept shifting about and a murmuring started up although the voices doing the murmuring sounded uncertain. Bright red, the man stood on the threshold with his briefcase pressed against his chest like armour. He asked his daughter to gather together all the guests and get them to leave his flat immediately. He refused to see them and went into the toilet where he locked the door and sat absolutely motionless on the toilet seat until he heard the door close behind the last of the guests. The story ended one week later with the daughter finding her father hanging from a beam in the sitting room, rigid in death although wearing newly polished shoes, a ludicrous attention to detail that would be his last.

It was stated that Alba Cambó had won a prize for the short story and that the jury had referred to ‘shame’, ‘loneliness’ and ‘the predicament of the modern man’ in their verdict. The prize was worth €1,000, and she said in an interview in the same issue that she was going to use the money to construct a garden on her terrace, which she seemed to have put off for some time as during the coming months we saw no sign of a garden or of any increase in the number of pots down there.

A month or two after we had read the story of a lonely man, another short story written by Alba Cambó was published in the same periodical. Mum bought this one as well. It was about a little boy who had been kidnapped from Majadahonda, a residential district for the better-off on the outskirts of Madrid. The search for the boy went on for days and weeks, but he was never found. Finally a call came from the man who had stolen the boy. The family was asked to pay a ransom. A week or two later the kidnapper was found in a rubbish bag. He had been brutally murdered; his arms had been cut off and, according to the autopsy that had been carried out, they had been cut off while he was still alive. He had also been subjected to sexual abuse. The boy was never found. This was a peculiar short story with rather a lot of loose ends – why, for example, had the man made his presence known and why should the reader believe that it was the boy who had led the killing of the man when there could just as well have been another kidnapper involved? Nor was there anything to suggest that the boy remained alive as well. There was an interview with Alba Cambó alongside this short story too. In it she said that the entertainment value of a violated female body was infinite and inexhaustible and that in writing about violated male bodies her aim was to explore the kind of entertainment value they offered. Rather unwisely she pre-empted the journalist’s questions by wondering rhetorically what was wrong with depicting violated male bodies when women’s bodies were continually being used in literature for that purpose? Some writers wrote like lazily masturbating monkeys in overheated cages, she said. They wrote as though they had lost the taste for the real flavours of a dish and had to keep adding salt and pork fat in order to make it taste of anything. Raped and murdered women here, raped and murdered women there, that was the only way the readers’ interest could be kept alive, said Alba Cambó.

The editor of the magazine had fixed on what she said about lazily masturbating monkeys. Alba Cambó on Lazily Masturbating Monkeys was written in bold above her image. This picture of her was not a particularly successful one. She was shown at an angle from the front with her lips slightly apart, an expression that actually made her look a bit retarded, even though Alba Cambó was not an ugly woman in reality. Mum said it was an unfortunate picture and an unfortunate piece of writing and that Alba Cambó might have gone a bit too far in what she said. In any case we both agreed that the first short story was better than the second. Mum put them both in a drawer in her bedroom where she kept magazine articles, obituaries and other things she felt somehow had to do with us.

Apart from the writing and the interviews there didn’t seem to be anything special about Alba Cambó. She fit in to the everyday life that was typical of the neighbourhood without any difficulty. Her hair was bleached and in rather poor condition, she was not in the first flush of youth and often had too much black around her eyes. She had a hoarse voice: it might have been the alcohol or the tobacco smoke that had damaged it, Mum thought. She was not particularly friendly and never initiated a conversation. On some days you would see her with one man and on other days with someone else. One of the men was tall and dark and said hello in a friendly way if you met on the stairs, although he never started up a conversation either. All of which made it difficult for us to form an image of Alba Cambó in those first few months. But her ceiling was our floor, and there was only a set of beams a foot or so thick separating our lives. This was something I often heard Mum say during the period following the publication of Alba’s first two stories. After all there’s only twelve inches separating our lives, she might exclaim on the phone or over a glass of wine one evening. We could hear the water rushing through the pipes when Alba Cambó flushed the toilet, and when she had a drink we could hear the tiny thud as the glass was put down on the surface of the counter. I am sure Mum entertained various notions about Alba Cambó she didn’t confide to me because even though I had read both the short stories I was far from being a sufficiently experienced conversational partner when it came to certain subjects. I think though that she must have spoken about Alba with some of her male acquaintances because on several occasions when one of them came to dinner, conversation would fall silent around the table when the sound of heels could be heard from the terrace below. The eyes of both Mum and her friend then turned towards the railing where they remained fixed as though they were both, each in their own way, visualising a version of Alba Cambó and what she was doing down there.

The building we lived in, and which I still write in, is located on Calle Joaquín Costa not far from the Universitat metro station. It is two storeys tall, built sometime in the 1940s, and has never been renovated. On the street outside shades of grey shift across the trunks of plane trees that look as though they have been attacked by scabies. But their leafy tops are healthy and in the spring they are light green; they darken in the summer and are shot through with warmer colours in the autumn. During the winter they are bare for a few months, but winters in Barcelona are short and mild and after a while the trees turn light green again. The foliage moves back and forth in the wind that comes in off the sea in the mornings and smells of seaweed and salt. On some days there is a tinge of oil in the air, from the port presumably. Even in those days our terrace was an oasis. Mum spent all her free mornings and evenings there. On it she had a deck chair and a round table where she would put a glass of wine while she smoked. From our terrace you could see part of the terrace below because it was slightly larger than ours and stuck out a bit more.

Our apartment was better on the outside than in. In Mum’s room you could see damp spots starting to form on the ceiling, and although my room was small it had a high ceiling, which made you feel as though you were sleeping in a can. The only window in the room overlooked a tiny inner courtyard. It was no more than a space for refuse really, and a means of letting light in, and had not been painted since the house was built. So my view consisted of a smooth dirty-grey surface the same colour as Blu-Tack or papier mâché. The whole building smelled in a way I believed at that time was the smell of an ordinary building but which I later realised was the smell of mould. And even though the refuse truck came every evening and the refuse space got disinfected, some vermin managed to survive. The cockroaches were red, several centimetres long, and had wings they could half-fly with. You would suddenly see them on the doorframe while you were brushing your teeth, and they would sit there calm and composed while washing their long reddish-brown antennae with their legs. The invasions were worse at the beginning of the summer and tailed off towards its end. Mum told me she had read a book by a Basque writer who suggested you should call cockroaches by name, which would make them impossible to kill. She experimented with calling one of them José María, and it really was impossible for her afterwards to crush him under her foot. This led to our having rather a lot of José Marías running over the floors on summer nights. Once I stepped on one as I was going to the toilet at night. Feeling its body scrabbling against my foot was revolting, and it was after that I decided to take things into my own hands. One night when Mum was at a friend’s, I went on the attack with a spray I had bought at the Chinese shop on the corner. I turned on the light, shifted the sofa and got spraying. Afterwards I could see them dying with their legs in the air like the sails of little windmills. As I swept them up I felt a pang of guilt that Mum’s José María probably lay among the cadavers. But new José Marías were bound to turn up, because there was an inexhaustible supply somewhere, and Mum would never have to miss her late friend.

There were maggots in the building as well although in their case Mum never suggested giving them names. It was almost impossible to get the better of these maggots, the caretaker said, because they seemed able to lay their eggs even in cement. They were everywhere and their shed skins turned up in flour bags and rice containers and on stale bits of bread. Eventually they turned into small moth-like creatures that were drawn to the light. You wouldn’t see them for a very long while, and then suddenly, as you were having your supper on the terrace or in the sitting room, talking about something nice and Mum might be sharing a bottle of wine with someone, a winged insect would come fluttering through the air like a reminder that their nests were still going strong and that the refuse space would never be entirely clean.

If any of the men friends who came to see Mum brought up the state of the apartment (they might, for instance, say it was nice but that the need for renovation appeared pressing if not to say urgent), Mum used to reply that yes, the flat we lived in was like a sinking boat. Just as you plugged one hole, another one burst open.

‘One fine day,’ she would say, ‘the water will flood in and it will sink to the bottom.’

She even joked about the need for renovation now and then and used to call the flat ‘our castle, our grave and maybe our mausoleum’. The men laughed incredulously when they heard her say things like that. Presumably they thought she had some kind of plan up her sleeve after all, and that a gang of craftsmen would arrive one day and knock down the plaster, break up the old flooring and take down the damp-stained ceilings. And they probably thought this woman needs a man, and perhaps just for a second or two they imagined what life would be like for them living with us, how long it would take them to get to work, where they would put their computers and their bookshelves, how much of the mortgage remained to be paid off, that they might be able to write the book they had always dreamed of writing in exchange for lending a practical hand and a bit of masculine glamour – ideas that might flicker past for a moment before vanishing. But not one of them ever took any practical initiative and I think they were wise to keep their distance from us. We weren’t a good match if it was financial freedom they were after. Mum’s salary working for the local government was hardly enough for any kind of extravagance and we lived on soups made of carrots, potatoes and chickpeas. We did eat meat, although, like the working classes of old, only on Sundays. Mum would often leave the soup-pot simmering for hours just like it was supposed to in the ancient recipes she worked from and which were based on the principle that many cheap ingredients could be made into something special provided they were allowed to cook together for long enough. The smell of those endless simmers found its way into all the nooks and crannies of the flat and seeped into our clothes as well, which was worse. Sometimes when I was away from home I would suddenly become aware of that smell of overcooked food. What’s that odour like mouldy old blankets, I might think, only to realise that the smell came from me. But there was a kind of pride in enduring, in bearing your cross and imagining that you were like a larva in its cocoon, trapped for now maybe but one day, one fine day, you would spread your wings and burst out and then everything would be utterly different. You couldn’t exactly imagine what it would be like, but it would be totally different and that was all that mattered. Meanwhile our motto had to be that we made the best of what we had. And if you had nothing, then you made the best of that too.

We continued to be curious about Alba Cambó, who published several more short stories in Semejanzas. Some of them were really violent, and frequently the violence was perpetrated by women and children against men. According to one of Mum’s male friends, a psychologist who taught at the Complutense University of Madrid, Alba Cambó’s short stories were unnatural and based on falsehoods about the human psyche in general and the male psyche in particular. The stuff about the psyche was not something we could judge. But we bought the magazines and kept them in the box for newspaper cuttings. I also think that Alba Cambó won some more awards, which led to some rather merry parties on her terrace, parties where people smoked marijuana, sang and laughed while we sat up there listening in the semi-darkness. She continued her excessive lifestyle well into the night as well. She did not come home until the early hours and always slept until late.

‘A real woman with a real life,’ Mum once said about Alba Cambó, and there was no mistaking a note of envy in her voice.

It wasn’t until a few days after she moved in that we realised Alba Cambó had not moved in alone. A new nameplate on the post box in the hall informed us that Alba Cambó Altamira and Blosom Gutiérrez Gafas now lived in the flat below. We saw Blosom that same evening, when we found her to be beautiful, black-skinned, and seemingly reserved and rather large. Mum said that she must be Alba’s personal assistant because she had to come from somewhere in Central America to judge by her accent. We would soon discover that she was just as uncommunicative as Alba Cambó herself, and never said hello if you happened to meet her on the street. She would stride past instead with an expression that declared ‘I know you are there but I have no intention of saying hello because we do not know one another.’ Her solemn and dignified manner (Mum referred to it as carrying her tail in the air) made it impossible to take the first step and start up a conversation of any kind. All the same she and Mum did begin talking one afternoon at the grocer’s. I have no idea what they talked about in the shop but when Mum came home the focus of her attention had shifted from Alba to her home help. Mum screwed together the coffee maker in the kitchen and, while she was putting out the cup and the sugar bowl, she said that observing Alba wasn’t particularly rewarding because she almost always sat still down there with paper and pen and a furrowed brow. The only action Cambó performed was focused on a cup she had beside her and which she drank from now and then, a movement not at all inspiring to a possible observer. Blosom, on the other hand, always had something going on. She hummed, laid the table, looked after the potted plants or laughed out loud at things she heard on the television or the radio in the living room. She shifted her body around in the heat in leisurely fashion, picking at Alba’s pots, removing dried leaves and watering them with the hose once the sun had gone down, so as not – as the women of the neighbourhood used to say – to burn the plants with water during the heat of the day. Sometimes she would go round with a pair of clippers, taking a bit off this plant and then that, moving some of Alba’s pots around and taking dirty wine glasses into the kitchen. From time to time she filled up the water in the little basin Alba had put up on one of the walls. Mum said that Blosom had acquired the habit of dipping her fingers very quickly into the little pool every so often when she passed it and then making the sign of the cross – it was a habitual movement, a reflex drummed in over years, decades maybe, and we wondered what Blosom’s religion actually was. There was a kind of stiffness to her way of making the sign of the cross, the kind of stiffness that comes with learned behaviours that have never become entirely natural to the person who has learnt them.

In the daytime Mum would sometimes hear Blosom and Alba talking while Blosom hung out the washing. They chatted like two girlfriends or sisters and there didn’t seem to be any differences between them then; when you shut your eyes and listened you couldn’t tell who was the mistress and who the servant. If Mum went close to the railing she could see Blosom bend over the washing basket and pick up an item of clothing or a sheet, and then stand up and peg the fabric to the clothes line. When she bent down again her buttocks could be seen straining against the material of her dress, and they were large, soft and round with the fabric stretched across them, damp with her sweat. I’ve never ever seen buttocks like that, said Mum. Sometimes it looked to her as though the cloth might split and those buttocks would then bloom through the hole in her dress. That was what she imagined, Blosom’s enormous buttocks suddenly bursting forth through a split in her skirt. And that wasn’t some sort of indecent fantasy, Mum said as if to defend herself, it was the only thing you could think as someone observing the situation: all that fabulous physicality in all its magnificence.

Soon, though, it was at night that the real encounters between Mum and Blosom took place, if you could refer to real encounters at this point. Because once the door had shut behind Alba, Blosom would start clearing the dinner things. She went back and forth between the table on the terrace and the kitchen; you could hear her piling plates and dishes on top of one another. Then it was her turn to go out onto the terrace with a glass of wine. First she wiped her neck and arms with a wet cloth and her breathing was strained as though she had been for a very long walk or a run. Then she relaxed. Her powerful arms lay along her body, her stomach distended and her gaze lost in the windows of the building opposite. From the chair Mum sat in she could see Blosom’s matted black hair sticking up just a few metres below. Mum used to sit there in absolute silence from fear that Blosom would think she was spying. Half an hour would pass in this way, an hour, sometimes even longer. Mum even wondered sometimes whether Blosom had fallen asleep down there. But then all of a sudden Blosom would get up, take the dirty wine glass with her into the flat and Mum would get up too and do the same.

At that time we used to buy our clothes at a market in Poblenou. I don’t know why we went all the way to Poblenou to shop for clothes, there were cheaper places nearer us, but Mum insisted on driving there. We used to go early in the morning, before the start of work and school, and when we arrived we were confronted by mountains of clothes, together with housewives and servants from the neighbourhood. We looked for bargains in the piles of underwear, skirts and quilted jackets of poor quality. If you found something you liked you pulled hard on the item of clothing, looking out of the corner of your eye at other people tugging at the same thing. Pitched battles could be waged in silence over beige knickers and nude bras at the market in Poblenou. When we drove home afterwards in Mum’s car, we sometimes stopped to fill up at the neighbourhood petrol station. Mum never filled up more than the reserve tank. I think that said something about our lives, because how can you call the reserve tank a reserve when it’s all you have?

Now and then we used to say how we longed to get away from this life and this building. How we were really nomads, not made to live between four walls, not suited to being locked in and having to live out our lives within ninety square metres. When we eventually shared these thoughts with Alba Cambó, she responded that it was true that you had to watch out for buildings because their main task was to maintain the decay going on inside their occupants. It does people good to wander, to be outside breathing clean air, she said. Letting yourself be confined inside walls just fuels the mould growing inside you. That’s right, Mum said. One day maybe we will get out of here, go off somewhere. What are you waiting for? Alba Cambó asked. I don’t know, Mum said. For Araceli’s father to come back maybe. Cambó laughed. Crap! she shouted then. You’re not waiting for any old dad, you’re waiting for Godot like everyone else.

So no Dad, not that I’ve lacked for stand-ins. Only my fathers have all been mayfly dads, the kind that are here one day and gone after three days at most. Some left traces behind, a khaki-coloured toothbrush in the bathroom, an inhaler, a book on a bedside table, and sometimes those traces would give rise to hopes that they might come back, come in the door to the flat and suddenly be struck by the idea that this really was a bit like returning home, that everything was already here – a home, a wife and a child – all they had to do was enter and start living. I wrote about all of them in my diary, and because their names eventually started to blur (Valerio, Enrique, Álvaro, José María) I began calling them ‘the Jogging Pants Man’, ‘the Chuckling Man’ and ‘the Tartare Man’ instead, and then their images would immediately reappear before me.

‘The Tartare Man’ once made himself a steak tartare on our terrace. I had no idea what steak tartare actually was until he explained with a lofty expression on his face that this was what sophisticated bohemians in Paris ate. The sophisticated inhabitants of Paris were people whose taste buds had not yet been destroyed by charred meat and fried onions. He took the ingredients out of the bag and put the tartare together in front of us. The tartare consisted of cutting up a packet of raw mince and mixing it right there and then with egg yolk, salt and pepper. Have a taste – it’s delicious, he said and offered the greasy plastic tray to Mum. She turned her head away and pretended not to look, but I did. His fingers closed hungrily around the mess and you could see the pleasure in his face as he pushed the morsel into his mouth. Uhhnn, he said. Then he swallowed and it was impossible not to think of a snake as his Adam’s apple pushed the mouthful down his throat. Please don’t let her let him move in, I thought, and she didn’t.

For his part ‘the Canary Man’ made his mark with a rather distinctive present. Before he arrived Mum explained that this man was wasn’t ugly, or attractive, but attractively ugly. He turned up one Friday evening, appearing in the gloom of our hall with a bottle he presented to Mum. Mum accepted the gift and put it on the linen cupboard.

‘Thank you,’ she said.