10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

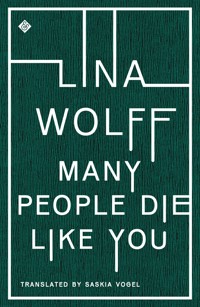

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

An underemployed chef is pulled into the escalating violence of his neighbour's makeshift porn channel. An elderly piano student is forced to flee her home village when word gets out that she's fucked her thirty-something teacher. A hose pumping cava through the maquette of a giant penis becomes a murder weapon in the hands of a disaffected housewife. In this collection from the winner of Sweden's August Prize, Lina Wolff gleefully wrenches unpredictability from the suffocations of day-to-day life, shatters balances of power without warning, and strips her characters down to their strangest and most unstable selves. Wicked, discomfiting, delightful and wry, delivered with the deadly wit for which Wolff is known, Many People Die Like You presents the uneasy spectacle of people in solitude, and probes, with savage honesty, the choices we make when we believe no one is watching … or when we no longer care.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 277

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

First published in English in 2020 by And Other Stories Sheffield – London – New Yorkwww.andotherstories.org

‘Nuestra Señora de Asuncion’ first published in Swedish by Granta, 1, 2013 and in English by Granta, 124, 2013.

'Year of the Pig' first published as ‘Grisens år’ by Dagens Nyheter, 2017; previously unpublished in English.

All other stories in this collection were published as Många människor dör som du by Albert Bonniers Förlag, Stockholm.

Copyright © Lina Wolff, 2009, 2013, 2017 English-language translation © Saskia Vogel, 2020

The right of Lina Wolff to be identified as author of this work and of Saskia Vogel to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or places is entirely coincidental.

ISBN: 9781911508809 eBook ISBN: 9781911508816

Editor: Anna Glendenning; Copy-editor: Ellie Robins; Proofreader: Sarah Terry; Typesetting and eBook: Tetragon, London; Cover design: Lotta Kühlhorn.

And Other Stories gratefully acknowledge that our work is supported using public funding by Arts Council England and that the cost of this translation was defrayed by a subsidy from the Swedish Arts Council and a grant from the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation.

Contents

No Man’s LandMaurice EchegarayMany People Die Like YouCirceOdette KlockareAnd by the Elevator Hung a KeyWhen She Talks About the PatriarchyVeronicaMisery PornA Chronicle of Fidelity UnforetoldNothing Has ChangedImagine a Living TreeNuestra Señora de la AsunciónThe Year of the PigNo Man’s Land

It’s not the first time I’ve seen a badly written report, but this one is worse than usual. Not that I have anything against dangling modifiers. I know how it is—to avoid a dangling modifier, one must be willing to sacrifice the flow. Perhaps he was not willing. But how am I to tell? You can’t tell whether a man knows how to modify just by looking at his face.

And the adjectives! From the very first line, the way they’re crammed in there is vulgar, and they go on to form a banal, soupy mess.

Language aside, the report is bizarre. It’s full of images, intimate images, and it has none of the matter-of-fact, concise, and streamlined qualities I requested. Furthermore, the photographs are out of focus. So much so that in certain images the people in question are barely identifiable.

“Text,” I’d specified when commissioning the assignment. “I want only text. Is that clear?”

“Yes,” he’d replied.

I meet his gaze. He looks away, and there’s no mistaking what underlies the writing of this report. Pity, and then something stronger than pity—the pleasure of presenting a certain kind of fact.

How perverse. As if I weren’t paying him enough.

I go to the liquor cabinet and pour myself a glass. I sit on the couch and take him in. He is tall, corpulent. Bulky. He could be my type, if you looked past his dullness.

“I presume the report is incomplete without commentary.”

“I have lots to say. May I sit?”

“Yes.”

He sits down and says:

“I usually start off my case presentations with a brief account of the subject’s life. Much of what I’m about to say will already be familiar to you, of course. But I’m telling you so you know what I know. So you know I crossed my t’s and dotted my i’s, so to speak.”

“I understand.”

“So, I shadowed your husband, Joan Roca Pujol. He works as an architect at an office in the center of Barcelona, Avenida Diagonal. At present, he’s working on a project for the town of Sitges. His brief is to restructure the town center in response to the large influx of homosexual tourists with serious spending power. There will be increased space for local trade, and the urban planning will foreground the area’s creative capital. Is this part of the report accurate?”

“Yes.”

“Your husband is spending a lot of time in Madrid. Which, taking into account his professional situation, he shouldn’t be. Your suspicion stems from these long stays in the capital. You suspect there’s another reason. A woman.”

“Or man.”

“In that case, I can confirm that this is about a woman.”

The corner of his mouth twitches, up and at an angle. It could be interpreted as a smile. I remember the fish I put in the oven just before he arrived. It should bake for exactly an hour, on gas mark seven. The table is already set; I set it right after lunch, as always. I was faithful to my habit. I am faithful. Loyal. I am loyal as a dog. A very dumb dog.

A woman, then. Hair color, teeth, chest size. What else? A city. Every person is a city, Joan says—occupational hazard. In his world, I’m like Verona. I’m like a balcony he can look up at, hoping some feeling might yet sprout inside him. Some he describes as Detroit, or Bonn. Perfect infrastructure but dull. Others are like Venice. The other woman may well be like Venice. As sticky as ice cream and hot. Stinking. Flaking facades. Yes, that’s it. That’s probably what she’s like. Mold-flecked masks and rotting foundations.

Decadence that knocks you senseless.

I have a few minutes before the fish has to be taken out.

“Continue.”

“Yes, a woman. Would you like to know her name?”

“No.”

“Well, it’s in the report. They meet every Thursday and Friday. Every other week, he spends the weekend at her place.”

“I understand. Now give me the details.”

He flips through the papers. Back and forth, looking at the pictures. Opening his mouth, closing it again. Theatrical. He shuts the report.

“May I speak from the heart?”

“Yes.”

“Then I’ll begin by saying—and I hope it will be of some comfort—that when they meet, your husband turns off the light as soon as he can. You see, her face frightens him.”

“Frightens him?”

“Yellow teeth. Smoking and obscene living. Her skin is ruined.”

“More details, please.”

“Details hurt.”

“My pain is none of your concern.”

“What do you want to know?”

“Everything.”

He says:

“The other woman—she lives in Madrid, by the way, on Calle Calvario—thinks mostly of her debts nowadays. Somehow, her apartment is full of them, and she thinks he, Joan, should toss her a few bills from time to time. Not large sums, but he does eat there and sometimes spends days in a row with her. Then there’s his bad habit of taking long showers after their… well, after their lovemaking. He must use upwards of 300 liters sometimes, according to the woman’s own calculations (which are probably incorrect—she isn’t the sort of woman who’s used to dealing with numbers, you get me?). But she has pointed out to him that she grew up wanting, so it’s not like she doesn’t know how to run a household, but there are all those wasted hours, time she could have spent doing other—profitable—activities. She’s preparing this talk she wants to have with Joan carefully. Suggestions like these can be misunderstood.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, he could mistake her for… a prostitute.”

“Say whore.”

“Well then. Whore. If that’s what you want.”

I take a drink. The heat spreads—as it does with this kind of whiskey. It’s like aftershave, but internal. I meet his gaze. Hold it. And he turns away. Of course, he wants a drink. He longs to have something in his hands, because this isn’t exactly going as he’d hoped. My silences and my word choices trouble him and so he wants alcohol. But he must wait; I’ll be the first to intoxication, that’s my prerogative.

“May I see it?”

He hands me back the report. Beads of sweat have formed around his nose.

I flip through the pages.

“Is it typical of the detectives’ guild to shoot out-of-focus images?”

“Typical of the guild? Do you have a lot of experience with detectives? Other than me?”

“One hears things.”

“We have to keep a certain distance. We can’t just walk over, stick the camera in their face, and tell them to say ‘cheese.’”

“I understand.”

“Then there’s her skin. It takes a while before you see what’s off about her face. But then you see it: a rough surface.”

“Which he loves. Continue.”

“The lines. There’s something severe about them. She is not a beautiful woman.”

“Which makes everything much worse. A surface can be erased. But not an interior.”

He looks at his hands. Says:

“In any case, those lines around her mouth are sharp. She says it’s unfair that you women must suffer time. You’re so soft, after all. She says time should handle you more carefully. But that’s not something that can be legislated, is it?”

He appears to be stifling a giggle.

I told you: he’s bizarre, just like the report. But he gets going after that giggle, perhaps thinking he can talk it away, wash it down with word mush. Pointing, gesticulating. Drawing flattering comparisons between me and the other woman. That’s what detectives do, what they’ve always done, in every book and throughout time. He’s probably thinking it won’t be long before I’m in tears. Then he’ll take a starched handkerchief from his jacket pocket, wipe my nose, and say “there, there.” And I’m supposed to put my head on his shoulder. Then the embrace, the cocoon of empathy, and his retainer for further assignments, leaving my account at the end of each month.

He gets up. Walks around the room. Stops by the shelf of family photos, and says:

“There are solutions.”

“Solutions?”

“Yes. We know how to get rid of people.”

Joan and I are smiling at each other in our wedding photo. Behind us is a wealth of happy people, and a bouquet of roses flying through a sky of white petals. I look out the window. You can see for miles today. It’s a beautiful night, very clear.

“Would you like to eat? Dinner’s ready.”

“No, thank you. But I’d love something to drink.”

“Gin? Vermouth?”

In a flash, I return with his drink.

“Let’s go back to ‘solutions.’ How would that work exactly? Would I get photographic evidence?”

“Oh yes, we can arrange all of that. And you can choose the murder weapon.”

“What a macabre term.”

“Macabre acts require macabre terminology. It doesn’t take much getting used to, and then it really is enjoyable. I have other examples—”

“That’s not necessary. I’m not interested.”

“Aren’t you?”

“Not at all.”

“So why the questions?”

“Female jealousy. Wouldn’t that justify exploring a hypothetical extermination?”

I laugh, and the laugh seems to echo. He is serious, sitting with his glass in hand. He’s not an ugly man. Not beautiful, not ugly. Perfectly average.

“You’re being glib,” he says. “As if you don’t understand how serious I am. If you want we can continue. Otherwise we drop it right now. When it comes to revenge, you have to make a choice. You can’t stay in no man’s land.”

No man’s land. The drink goes to my head, and this is precisely what I’d like to discuss. The no man’s land. I have an exceptional tolerance for the no man’s land. Drip a drop of that on the threshold and you’ll see how it expands, spreading through the room and the entire marital abode, and finally entering me. Then it continues out into the city and disappears. Soon it’s gone, vaporized.

“Aha.”

He squirms. Says:

“She’s just a simple whore.”

“I’m sorry?”

“Or slut, because she doesn’t even know to get paid for it.”

“Do you think insulting her will get you a bigger tip?”

“Now you’re the one insulting me. But I suppose that’s how it goes: the insulted insult. The darkness has to go somewhere.”

I go to the kitchen. Take the fish out and light the candles on the table. I hear his voice. It sounds happy, surprised, excited.

“A phallus!”

He’s walked into the office and is at the drafting table.

“What a fantastic drawing! Is it yours?”

“No, it’s Joan’s.”

“Aha, I’ve watched him work, but you never see the finished product through the window.”

“It’s the best thing that’s been drawn on Sitges’ dime to date.”

There’s something about that picture. It makes everyone who sees it happy, exactly as it’s supposed to. I’m no exception.

“It’s a proposal for a fountain, did you know that?”

No, he did not, and I tell him. The idea: stiff and straight, water spraying from its tip. A towering urban orgasm, you could say, to take place day and night, thirty meters above people’s heads. In Sitges you’ll look up at it, this fountain, and you’ll be penetrated by elation. You’ll welcome it.

I can’t stop talking about it:

“Of course, the newspapers allowed themselves to be provoked at first. It caused outrage and censure. They tried to drag Joan’s name through the mud, and that made him laugh. I was the one who’d made the clay mock-up, the one we placed in the model of Sitges, surrounded by the square and the building’s facades. We made a joint presentation to the heads of the town. The mayor sat there, looking serious and lost. ‘A phallus. A phallus. A phallus!’ he finally exclaimed, and for a few moments his face actually broke into an almost happy, if not sunny, expression. I’m trying to archive that image of the mayor in my mind, because he is almost always depicted in a dreary, newsprint sort of way, which makes you think he’s a man without a face, and heart. The mayor, that is.”

“I understand.”

I decide to show him the clay miniature. I have one in iron too, which I cast and threaded a hose through so you can watch it gush.

“The day we presented it, we bought cava from the mayor’s hometown. We hooked it up to the hose and let it rain on the chamber.”

I’m laughing. But he looks grave.

I hurry to the kitchen. Salt-encrusted fish, lukewarm and still edible, and various salads.

“Are you sure you don’t want a bite?”

“What about him? Are you sure he won’t be coming home?”

“He never comes home on Fridays.”

I had to stop myself from adding that he has meetings.

“So who did you cook for today? For me?”

“No, for him.”

“But you said he doesn’t come home on Fridays.”

“You never know.”

“I’m sorry, but this is hilarious. You’re sitting there with dinner cooling on the stove while he’s pleasuring himself with another woman. You’re unbearable. He must hate you.”

“We work together. We have a lot in common. And it’s none of your business what I do in my solitude. Cooking is quite an innocent pursuit.”

“I don’t know about that.”

He’s getting drunk. When I fetch something from the kitchen or even move for the wine across the table, it’s as though he’s reaching for me.

“Tell me about him.”

“Excuse me?”

“Tell me about him. I’ve been following him for so long, after all. Your husband walks very slowly, I’ll tell you that for free—shadowing him takes patience. He stops to look at anything that moves; you’d think he were a kid if his age weren’t so obvious.”

“Your words, not mine.”

“Don’t be so la-di-da. Tell me about you. How you do it.”

“What?”

“It.”

“What?”

“Don’t be coy. Tell me how you fuck.”

“I think it’s time for you to go. I’ll get the checkbook.”

“That can wait.”

“You seem like a simple man. Drab and simple. You should leave.”

“I don’t think so.”

“I’ll call the police.”

“Whore.”

“John.”

“Whore.”

We laugh. We’re drunk now. So drunk I knock over the wine bottle. The wine spills across the table and stains his pants.

“It happens,” he says.

“You can’t sit around like that. Wet.”

“I guess I’ll have to go home, then.”

“You can borrow a pair of my husband’s trousers. I’ll go get a pair.”

“I’ll come with you. I haven’t seen the view from the bedroom yet.”

There’s something about the light, how it moves as the buzz goes to my head. The sea turns a strange blue. The sea should be seen facing west, not like here: facing east. East is for dawn people. We are not dawn people. Not me, not the detective, not Joan.

“Cigar?”

“No, thank you.”

“A bad habit my husband has after meals.”

“You think about him all the time. And smile. It’s like rain and raincoats with you—the truth can’t get a foothold, doesn’t get in, it just rolls right over the surface then evaporates.”

I like him. I feel like telling him how I do it, and then asking him to tell me how he and his wife do it. Or he and his whoever. But he’s earnest. It’s like he’s suddenly not in the mood anymore. I get on the bed, puffing the cigar and blowing smoke at the ceiling. I’ve always liked seeing smoke from this perspective. Dispersing at the ceiling. Spreading in small ringed clouds, like an atom bomb in miniature.

“Does he smoke in bed?”

“Who?”

“Your husband.”

“He smokes where he wants. In bed, in the bathroom, and the kitchen.”

“And the butts…?”

“On the floor.”

“And you follow him around, sweeping up.”

It’s the liquor, it’s the whole situation, it’s the fountain: the elation inside me won’t sink. It rises and falls like a wave. And the hand grabs for me again, searching, methodical. That’s the kind of man he is, the detective. Methodical in his work, and perhaps a little loving.

“Tell me about how they do it. My husband and her.”

“What?”

“How they fuck, of course.”

I’m laughing at myself: imagine, me, talking like this! And he tells me. Soon I want to drag myself out of my stupor—it needles now, right as I was getting to a safe place.

“Wait.”

The idea comes from the drink, yes, it does, because we can’t deny we’re drunk now the wine bottle is empty and some of the pear cognac has been drained from the potbellied bottle. The report is on the coffee table, shut, the cover stamped with rings from the wineglasses. Of course, it would have been more appropriate for me to sit there, commenting on his work and allowing myself to be cocooned in gloom.

Appropriate. That’s a funny word. Where did that come from?

“I have to show you the fountain in action.”

I open the closet and take out the iron model, get a bottle of cava from the refrigerator, go into the bathroom and uncork the bottle, stick in the hose, and push the button. The cava sprays the entire bathroom.

“Look!” I shout. Now he’s laughing, too.

I raise the bottle, put it to his mouth. I drink. I wind the hose around his wrists. His lips look kissable. He says no one has ever put him in bondage before. He doesn’t have a lot of hair, is mostly bald. His breath is sour. He is disgusting.

I tug at him.

“Let’s play a game. Come on. Lie on your belly. Bend your knees, put your feet to your ass. Like that. Hands tied behind your back, then a hose around your ankles and the same hose around your neck. It’s a fun game. Lie still.”

He obeys. He must be quite drunk. He was nice while he was letting me talk about the business with the no man’s land. He was nice for a while after that, too, but now it’s as if the niceness has vanished and been replaced with the quality I didn’t like from the start.

I sit on the toilet, flipping through the report.

“The report is bizarre. There’s a lot that disturbs me here.”

“Sure, let’s talk about it. But take the rope off.”

“You mean the hose.”

“Yes, take the hose off. I thought this was a game.”

“This is a game.”

“Yes, but when does it start?”

“It’s not one of those games. Let’s talk about the report.”

“You have to take the rope off.”

“The hose.”

“The hose. You have to take the hose off. It’s strangling me every time I relax.”

“Yes. That’s the game.”

“Take it off. I can’t handle it anymore. I have to vomit. I’m drunk.”

“As I said, I think the report is bizarre.”

“It’s just a normal report, for Christ’s sake.”

“There are too many pictures. I think it puts my husband and his lover in a bad light.”

“Isn’t that what you want?”

“Why would I want that?”

“Because you’ve been spurned! I just did what I thought you wanted. Why hire a detective if you don’t want the truth? Why did you want me to deliver it in person if you didn’t want sympathy?”

The light in the bathroom is moving. Reflected light pounces across the shower curtain. In spite of the baldness and the corpulence, his voice is shrill. I don’t like his voice.

I crawl in between the wall and the toilet. Cover my ears. Belt out a song I learned in school. It’s about fish who drink up their own river, drinking and drinking as they’re swimming around in the water. Meanwhile, the Virgin Mary is combing her hair at the water’s edge. Why is she combing her hair at the edge of the water and why are the fish drinking their own river?

I start rocking, I can’t help it, he must think I’m crazy. Joan must be coming home soon. The last plane from Madrid has left, contrails drawn across the sky. I should clear the table. Should tidy up. Gather myself, but there’s something else inside me, too, a new no man’s land. It’s what’s spreading inside me—I’m the gauze, and the no man’s land is the ink I’m soaking up. I take my hands from my ears and scream that at him, that I am the gauze and I’m absorbing this land now, and I can’t stop and I can’t help him until it’s done. Doesn’t he understand? Doesn’t he see that I’m suffering, too? It’s not enough that I’m suffering—I’m paralyzed. So paralyzed I can’t set him free. I get this way sometimes. It’s not my fault, it just happens, it’s a part of me.

Silence, finally. One of those audible silences, one of those silences where I don’t dare open my eyes. I fall asleep, but not before telling myself to drink three glasses of water, otherwise the headache will be blinding and my eyes will be like gravel.

Joan’s steps on the stairs wake me. The no man’s land is gone, and I almost feel a lightness. The bathroom door opens and I see his shoes. He’s standing there, silent.

Then he puts his hand on my head, and it is large and hot and caressing.

“Darling,” he says. “Not again.”

Maurice Echegaray

This happened when we were living off the southbound highway. Our apartment shared a stairwell with Maurice Echegaray’s office, and there were three doors between his and ours. If Mom ran into him on the stairs, he’d complain about the cooking smell from the apartments seeping into his office through the vents. Mom said she wasn’t about to stop eating just so he could sell whatever it was he was selling. Sometimes he gave me looks. Sometimes I stubbed my cigarette out by his door. There was a sign on it: Maurice Echegaray Trade Management. The sign was made of gold plastic, and if you pressed your nose to it, it smelled synthetic. Once, he flung open his door on me. Said: You creep, you’re following me. You wish, I said, and he said excuse me and I repeated myself: You wish.

And that was it. He just watched me go, and his silhouette was slender in the light from the stairwell’s window. From then on, when I met him in the entryway or in the garage he was always wary of me, like I was vermin or just any old bug.

Otherwise, not much used to happen in our stairwell back then. Two days a week an old lady came to clean. One time a pipe burst and the floor flooded. If you said that to one of those old ladies on the stairs, I mean if you said to them that there wasn’t much going on here, they’d say things never stopped going on: our neighborhood used to be full of sheep stalls, orange groves, and an old porcelain factory that so-and-so’s old man had worked in when he was young. Then the cranes arrived. New facades, shiny facades, facades that reflected the sky. Price Waterhouse, Inditex, Iberia. On the rooftops were green oases with pools for the employees, who were bank directors, consultants, and other smooth operators.

“Up there, the traffic sounds like the ocean,” my friend Isabel told me. She’d been up there once. “You can lie on a deck chair, drink a margarita, and pretend you’re in the Bahamas, but really it’s just Valencia.”

Dad said it was nice to live here now. With all the new developments, the neighborhood was really coming up.

“I don’t know about ‘nice,’” Mom said. “The new parts are quite nice, but what we have is actually quite ugly.”

And she was right. From the balcony, you could see our house reflected by the new, and that mirror image set the defects in sharp relief. Discolored and washed-out clothes hung on laundry lines strung across the balconies. Bricks showed through the plaster. The awnings gave a pop of color, but exhaust fumes had turned their orange grimy. It was difficult to understand why Price Waterhouse would set up shop across from a building like ours, in the same way that it was difficult to understand why someone like Maurice Echegaray wanted an office in our building. Or why someone would put a gym here. It was on the ground floor of the building across from us and had a Turkish bath and an ice machine with ice chips to rub on your skin. No cellulite in the world was a match for that, according to the people who worked there. When the gym’s doors slid open, the smell of luxury wafted out onto the street, which otherwise mostly smelled of exhaust fumes and burnt earth. You could stand outside those doors, inhaling that scent of luxury, but someone would eventually come along and tell you to make up your mind: are you in or out?

It was only after the ad appeared in the newspaper that I had a chance to really get to know Maurice Echegaray. The very same week I graduated high school: Maurice Echegaray Trade Management Seeking Qualified Personnel.

“Will you look at that,” Dad said. “The Frenchman is expanding.”

“What a coincidence,” I told Isabel. “The very same week I’m graduating.”

I called the number in the ad. An answering machine picked up, and a mechanical voice said that Maurice Echegaray couldn’t be reached. I said my name was Almudena Reyes. I lived three doors away and could imagine working for Maurice Echegaray if the pay was halfway decent. He could call me, or stop by if he preferred. I thought about adding something about my education, but the beep interrupted me and calling back felt silly.

I waited. Summer was on its way, and the thermometers on the street read twenty-nine degrees. Haze veiled the sky. In the evenings the cockroaches ran in and out of the drains, and sometimes we chased them, trying to smash them with a shoe, and when we succeeded, there was a crunch and then a dark stain on the sole.

Maurice Echegaray didn’t call back. Nor did he stop by. I applied for other jobs, too, but they didn’t get back to me either. I waited a whole week, and then halfway through the second week I rang his doorbell.

“I’d like to work here,” I said when he opened the door.

“I don’t need any help,” he replied.

“It said you did in the paper.”

Maurice Echegaray fixed his eyes on me. His nose was crooked, his skin dark. His white suit had a silky sheen, and he was wearing gold-plated cuff links. There was a whiff of expensive perfume around us. Then he let me in. The apartment was the same as ours: you walked into a small hall and the living room was straight ahead. There was a set of black leather sofas that looked kind of sticky, backlit from the street.

“You’ve grown up,” he said.

“Yes,” I said.

We talked for a while. About the building in general, the neighbors and their children, the cranes and how hard it was to find a job nowadays, how no one was lining up to hire anyone. Then we sat in silence. You could hear someone walking around upstairs, water rushing through a pipe.

“I only employ professionals,” he finally said.

He clasped his hands in his lap. Crossed his legs.

“I see,” I said.

“Them’s the breaks.”

I said I was a quick study. All my teachers had said so: I had potential.

“Would you call yourself a pro?” Maurice Echegaray asked.

“No,” I said. “Not a pro. I’m saying that because I prefer not to lie, especially to myself.”

That line usually hits home with people, but Maurice Echegaray shook his head and said it was a shame I didn’t like lying because in business, lying was essential. Essential. And if you could manage to lie to yourself, that was even better, as far as believability goes.

“But maybe you can learn,” he said. “If you have so much potential.”

Silence again. He asked me if I wanted coffee, and I said no. He asked me if I wanted a glass of water, and I said yes. He left the room and came back with a glass of water that tasted of chlorine.

“I need someone to answer the phone,” he said. “And since you already live next door, well.”

I shrugged. An answering service. That was nothing to brag about, really. Though you could start at the bottom and work your way up. Some people do that: they get in at the ground floor and end up top dog. So I said yes, and we agreed I would start the next day, and if there was anything else he needed help with, I said, all he had to do was shout. The telephone hadn’t rung once that entire time.

I had been right about the phone, it didn’t make a sound. The first afternoon went by slowly; I mostly listened to Maurice Echegaray talking on the phone in his office. His voice came through the half-open office door. Sometimes it sounded upbeat, sometimes it sounded angry. When he was angry, he spoke slowly, overarticulating each syllable, as though he were speaking to an idiot. I eavesdropped a lot, but mostly I was bored. I got acquainted with the office. The black leather sofas were still shabby, and upon closer inspection the place was actually pretty messy. I emptied ashtrays and vacuumed. I watered the flowers and saw that he’d stubbed out his cigarettes in the pots, too. I cleaned the toilet, and on the mirror I used a blue spray I’d found in the cleaning closet which stank of ammonia. Then I aired the place out, created a through breeze, got rid of the stale air, even if the air that came in was hot and nauseating.

When Maurice Echegaray was leaving for the day, he said:

“It looks nice in here. Just pull the door shut when you leave.”

I waited until the door closed behind him. Then I went into his office, opened the drawers, and found his cigarettes. I sat on his chair and put my feet up on the table. I sat like that for a while, leaning my head against the headrest and looking out the window. You could see the Price Waterhouse logo across the way, mirrored glass, and a bit of sky, patterned with contrails. I drew the smoke into my throat, coughed, and put the cigarette out in the newly emptied ashtray.

Then I stowed the vacuum in the cleaning closet, poured out the mop water in the toilet, and went home to my mother, who asked how my first day at work was.