Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

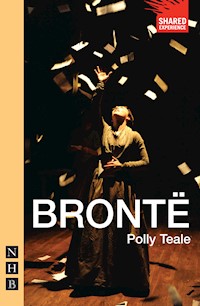

A compelling literary detective story about the turbulent lives of the Brontë sisters - dramatised by Polly Teale and Shared Experience, the team behind After Mrs Rochester and Jane Eyre. In 1845, Branwell Brontë returns home in disgrace, plagued by his addictions. As he descends into alcoholism and insanity, bringing chaos to the household, his sisters write… Polly Teale's extraordinary play evokes the real and imagined worlds of the Brontës, as their fictional characters come to haunt their creators. Brontë was produced by award-winning theatre company Shared Experience in 2010, in a co-production with the Watermill Theatre, Newbury, directed by Nancy Meckler. Shared Experience are acclaimed the world over for their powerful, visually-charged productions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 118

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Polly Teale

BRONTË

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

An Interview with Polly Teale

Author’s Note

Original Production

Dedication

Characters

Act One

Act Two

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Reality and Fiction

An interview with Polly Teale

This isn’t the first time you’ve been drawn to the Brontës. How did it all start?

Ten years ago I adapted Jane Eyre for the stage. I was intrigued by the mythic power of the madwoman, by Brontë’s repulsion and attraction to her own creation. Her danger and eroticism. Her terrifying rage. I wanted to explore what this figure represented. How she came into existence. To do this, I needed to research Brontë’s life and times. To see how the madwoman had been born in reaction to the Victorian ideal of femininity. How she had grown out of the Victorian consciousness. Later, I went on to write a play about Jean Rhys, who wrote a book inspired by Jane Eyre. Wide Sargasso Sea was a prequel, imagining the madwoman’s life before she was locked away. Giving her her own story. In Jean’s book, the madwoman was no longer a monster. We discover her as a child, follow her journey, her growing alienation, knowing of course where it will end. The book became a modern classic. The madwoman was out of her attic, back on the run, ready to stray into our fiction in whatever form she might choose; a potent symbol of female power and psychosis.

This third and final piece is a return to the source, the beginning, the Brontës. I wrote the play with a question in my mind: how was it possible that these three women, three celibate Victorian sisters, living in isolation on the Yorkshire moors, could have written some of the most passionate (even erotic) fiction of all time? How could they have created such potent psychological portraits that they would come to haunt us, becoming a part of our collective consciousness?

But why return to the Victorians? Things have changed so much for women. What can the Brontës tell us about our own lives?

Yes, of course things have changed, yet we are still hugely drawn to these stories, these characters. Jane Eyre is believed to be the second most-read book in the English language (after the Bible). Wuthering Heights remains one of the great literary creations of all time and is still a bestseller. Today it is difficult for us to imagine a world where women were not allowed to enter a library, where women had to publish under men’s names, where women had no part in public life. And yet one hundred and fifty years is not so long ago. Their struggles are not so distant. A century and a half may be long enough to change laws and even statistics, but how long does it take to change our thinking? Our deeper understanding of who we are and what’s possible for us? Writing the play also made me think about the cost of greater visibility, greater ambition. The way that it can distract and distort. The way it can undermine the sense of self. Branwell is perhaps the most tragic figure in the play, ruined by the weight of other people’s expectations, by fear of failure, the pressure to succeed.

Why mix fictional and real characters onstage?

The external lives of the Brontës were dreary, repetitive, uneventful, yet their inner lives were the opposite. To be able to dramatise this collision of drab domesticity and soaring, unfettered imagination, to be able to see both the real and internal world at once, was essential if we were to understand their story.

But Cathy and the madwoman function in different ways. Cathy is in the house because Emily is creating Wuthering Heights. She is alive in Emily’s imagination as she conjures her up to write. She is an embodiment of Emily’s longing to return to the free state of childhood. The madwoman has a different relationship to her creator, Charlotte. She is an expression of everything (sexual longing, rage, frustration) which Charlotte wishes to disown, to conceal from others. She erupts out of Charlotte’s unconscious and must be constantly stifled or locked away. In the second half, when Jane comes to life, Charlotte takes on the role of Jane, casting herself as the ‘good angel’, the moral centre of the story and antithesis of the madwoman. If Jane is an idealised version of Charlotte, then the madwoman is everything that she, the Victorian woman, is not allowed to be.

What about Anne? Why isn’t she haunted by one of her fictional creations?

Anne’s writing had a much stronger social, political agenda. It was less about her deep unconscious needs, her inner world, and more of a social document; a tool to provoke reform, to expose injustice.

There are several references to the social changes that are taking place. It was very important to me to place the Brontës in history, to know that they lived at a time of huge social upheaval. The changes they were witnessing during the Industrial Revolution were the beginnings of everything that has come since. The conversations they have about the working conditions at the mill could be about contemporary sweatshops. They were there at the beginning – the sense of emerging capitalism, of the huge possibilities and dangers of mechanisation. It’s all there.

What was it like to write about real people? Does it liberate or restrict?

The first three months of work on the play was all research. At one point I thought my head would explode with all the information, the wonderful detail, the endless dates, the theories of the biographers. I think though, in the end, you have to decide what it is about this story that fascinates you here, now, in the twenty-first century. The danger of biographical work is that it gets bogged down in event, in detail, in the surface narrative of the life. You have to be pretty brutal and chuck out anything that isn’t relevant to your bigger question, your theme.

You want to be able to dig down, not just move forward through the story. To do that, you have to make space. For those who know a lot about the Brontës, they will notice huge omissions and also the occasional liberty! In the end, though, this is a response to the Brontë story, not a piece of biography. That’s the reason I begin the piece in modern dress. I didn’t want to pretend this was real. I wanted us to look at it through the filter of time, to know that we are playing a kind of game: dressing up, trying to imagine, putting ourselves in their shoes, joining all those before us who have done the same. After all, this is a story of make-believe, of the power of the imagination to transcend time and place, to take us to places we cannot otherwise go.

This interview was first published in the Guardian on 13th August 2005

Author’s Note

The play begins with a Prologue during which the actors change from modern dress into Victorian costumes. As they change they shift into character.

The present tense of the first half of the play is set on a day in July 1845 when Anne and Branwell return from Thorpe Green, where they have been working as governess and tutor. At this time Emily was writing Wuthering Heights and Charlotte about to write Jane Eyre. Hence the presence of Cathy (the heroine from Wuthering Heights) and Bertha (the mad woman from Jane Eyre).

Cathy and Bertha appear on stage as they surface in the minds of their creators. Cathy appears much as she is found in Wuthering Heights. Emily is writing the section where Cathy is feverish and delirious, close to the end of her life. She has torn open her pillow and is obsessively trying to remember the names of the birds from which the feathers come, in the belief that it will reconnect her to her childhood, to the free, primitive self that exists before self-conciousness, before socialisation. The image of Cathy unable to recognise her reflection, unable to recognise her adult self in the mirror, is central to both Cathy and Emily’s crisis. Their fear of being neutered, being destroyed by conformity.

Bertha, the mad woman from Jane Eyre, first surfaces in Charlotte’s childhood fantasy of herself as the exquisitely beautiful daughter, admired by all. Later Bertha becomes an expression of the part of Charlotte (sexual longing, rage, frustration, loneliness) which she wishes to disown, to conceal from others. In the second half of the play, when Jane Eyre comes to life, Charlotte takes on the role of Jane, casting herself as the ‘good angel’, the moral centre of the story and antithesis of Bertha.

The rest of the first half is a series of flashbacks which progress through the Brontës’ childhood, returning to July 1845 towards the end of the act.

Polly Teale

Brontë was first performed by Shared Experience Theatre Company at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, Guildford, on 25 August 2005, and subsequently at West Yorkshire Playhouse, Leeds; Warwick Arts Centre; Project Arts Centre, Dublin; York Theatre Royal; Oxford Playhouse; Liverpool Playhouse; the Lyric Hammersmith, London and The Lowry, Salford. The cast was as follows:

CHARLOTTE

Fenella Woolgar

EMILY

Diane Beck

ANNE

Catherine Cusack

MRS ROCHESTER (BERTHA) / CATHY

Natalia Tena

BRANWELL / ARTHUR HUNTINGDON / HEATHCLIFF

Matthew Thomas

PATRICK / ARTHUR BELL NICHOLLS / ROCHESTER / MR HEGER

David Fielder

All other characters played by members of the company

Directed by Polly TealeDesigner Angela DaviesComposer and Sound Designer Peter SalemLighting designer Chris DaveyMovement Director Leah HausmanFeaturing images by Paula Rego

Brontë was revived by Shared Experience Theatre Company in a new production co-produced by the Watermill Theatre, that opened at the Watermill Theatre, Newbury, in April 2010. The cast was as follows:

CHARLOTTE

Kristin Atherton

EMILY

Elizabeth Crarer

ANNE

Flora Nicholson

MRS ROCHESTER (BERTHA) / CATHY

Frances McNamee

BRANWELL / ARTHUR HUNTINGDON / HEATHCLIFF

Mark Edel-Hunt

PATRICK / ARTHUR BELL NICHOLLS / ROCHESTER / MR HEGER

David Fielder

All other characters played by members of the company

Directed by Nancy MecklerDesigner Ruth SutcliffeComposer and Sound Designer Peter SalemLighting designer Tim LutkinMovement Director Liz Ranken

BRONTË

For Ian and Eden

Characters

THE BRONTË FAMILY

PATRICK

CHARLOTTE

BRANWELL

EMILY

ANNE

CATHY

BERTHA

The actor playing Patrick also plays

ROCHESTER

MR HEGER

ARTHUR BELL NICHOLLS

The actor playing Branwell also plays

HEATHCLIFF from Wuthering Heights

ARTHUR HUNTINGTON from The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

A dash (–) indicates that the speaker is interrupted at that point.

An ellipsis (…) indicates that the speech trails off.

ACT ONE

The stage looks like a rehearsal room towards the end of rehearsals. Objects from the world of the play silted up around the room along with various pieces of Victorian furniture. Everywhere there are books. Some old. Some modern books about the Brontës.

While the audience enters the actors are already onstage wearing modern rehearsal clothes. They will change into Victorian costumes during the Prologue.

They are sitting at a table studying books about the Brontës.

EMILY. How did it happen?

ANNE. How was it possible?

CHARLOTTE. Three Victorian spinsters living in isolation on the Yorkshire moors.

EMILY (examining a picture in a book). It’s hard to believe that they really dressed like this, for walking on the moors, carrying in coal, scrubbing floors.

ANNE. Writing books.

CHARLOTTE. Here’s the painting done by their brother Branwell, now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery.

She takes a biography from the actor playing BRANWELL BRONTË and looks at the cover, on which is BRANWELL’s painting of the sisters.

There is a smudge in the middle where he has painted himself out. She looks too fat.

The actors peer at the portrait.

ANNE. Too miserable.

EMILY. Too pinched.

CHARLOTTE. Not that they were pretty. Not at all.

ANNE. Their lives would have been different if they had been. They would have married.

EMILY. Died in childbirth.

CHARLOTTE. Or had lots of children and never written another word.

ANNE. Perhaps the odd recipe, a letter here and there, but nothing we – (To the audience.) would know about.

CHARLOTTE. They would be gone.

ANNE. Lost.

CHARLOTTE. Sunk without trace.

EMILY. In the deep dark river that claims us all.

Beat.

ANNE. We have no mother. Can none of us remember her. That’s why our books are peopled by orphans. Children abandoned.

EMILY. Lost.

CHARLOTTE. Alone.

ANNE. We cannot imagine what it would have been like to have kisses and cuddles. A woman’s soft touch. Her warmth and forgiveness.

CHARLOTTE. Perhaps that is why we’re so uncommonly close. So uneasy with strangers.

ANNE. Perhaps that is why we have little patience with children. Why we are utterly ill-suited to the only job available to us.

ALL. Governess.

ANNE. There are stories about our mother, things we’ve been told. A bird was once trapped in the house. It flew again and again at the window. Broke its wing, its beak, its leg. She kept it and nursed it back to life.

CHARLOTTE. No mother. Can’t remember. Not a word, not a look. Not a smile.

EMILY. We were lucky.

CHARLOTTE. Lucky?

ANNE. How so?

EMILY. She was not there to criticise. To insist on ladylike manners, pretty clothes and gentle speech. To organise tea parties with eligible men. We were allowed to read whatever we found. Whatever we could get hold of.

The actor playing PATRICK BRONTË brings a pile of books and places them on the table. Leaves. CHARLOTTE, EMILY and ANNE read the spines.

Milton. Byron. Shelley.

CHARLOTTE. Scott. Homer. Shakespeare. Brontë. Patrick Brontë… Yes. (Pause.) Our name printed on the spine in beautiful curling letters.

PATRICK joins them.

ANNE. Our father, born Brunty, an Irish peasant, had himself published, at some expense, a volume of poems and a book of sermons that sit alongside the rest.

PATRICK. The word. It is this alone which separates us from animals. The power not only to live but to know