Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

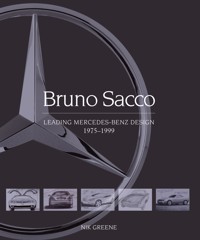

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

When Bruno Sacco walked through the doors on his first day at Mercedes-Benz on 13 January 1958 it is highly unlikely that his Daimler-Benz colleagues could ever imagine that this nervous young man would not only revolutionize design but would change the way design and innovation connected with brand tradition forever. Bruno Sacco is one of the most influential automotive designers of the late twentieth century; many models launched during his era now characterize the Mercedes-Benz brand. When Nik Greene asked Bruno Sacco to assist with this book, he replied humbly 'No-one designs a car alone, and more to the point, I never, for one minute, wanted to. From the moment I became Head of Design, I put down my pens and became a manager of minds.' With over 330 photographs and illustrations, this book includes an overview of the early days of functional vehicle design; the influence of safety on design evolution; protagonists of Daimler-Benz design from Hermann Ahrens to Paul Bracq; design philosophy and innovation under Bruno Sacco; the Sacco-designed cars and, finally, the Bruno Sacco legacy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

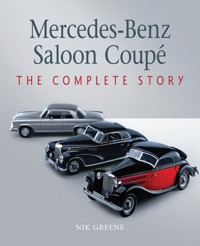

Bruno Sacco

LEADING MERCEDES-BENZ DESIGN1975–1999

Bruno Sacco

LEADING MERCEDES-BENZ DESIGN1975–1999

NIK GREENE

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Nik Greene 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 718 7

CONTENTS

Preface & Acknowledgements

Milestones of Mercedes-Benz Design

CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY DAYS OF AUTOMOBILE DESIGN

CHAPTER 2 DESIGNING THROUGH SAFETY AND ACCIDENT RESEARCH

CHAPTER 3 THE PROTAGONISTS

CHAPTER 4 SHAPING THE BRAND THE SACCO WAY

CHAPTER 5 THE MODELS

CHAPTER 6 SACCO'S LEGACY

Index

PREFACE & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In general, I don’t have heroes in my life. Having encountered many ‘celebrities’ over the years, I tend not to be fazed or awed by their presence. However, once in a while, I have had the privilege of meeting someone who came as close to what I would probably class as a hero, should I take the time to define the term. Bruno Sacco, someone whose work I had followed since my early teens, is one such person.

In the days before the internet, when information was not so easily acquired, I used to travel regularly to main dealerships to ask for car brochures and catalogues. I would collect car magazines and books and stand at a library terminal scanning newspaper articles, looking for a whisper of what the next model of Mercedes-Benz would look like. Occasionally, there would be a reference to a stylist or designer by the name of Bruno Sacco. Never in my wildest dreams did I think that I would, one day, be standing in front of this man.

Writing this book has been exciting, but it has also been frustrating. I have met and spoken with many people connected with either Bruno Sacco or design at Mercedes-Benz and not one person spoke of him or his work with anything other than praise and admiration. During the hours I spent with him, he was endlessly humble and modest about his achievements. There was not a hint of ego.

At the end of our first meeting, I asked him whether he had ever thought of writing an autobiography, or agreeing to someone telling his story. He looked at me in dismay. ‘Why?’ he said.’ I did nothing on my own. Everything we did, we did as a team; everything we did, we did for Mercedes-Benz. If you want to write about me, write about design.’

So here it is. The only way I could honour one of the greatest designers in automotive history was to write his story through the history of design, honouring the people he honoured, and showing his talent through his work and not through his ego.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

At times, writing can be a solitary act and it can feel especially lonely as one stares at a screen with dry eyes for hours on end. However, there are times when putting a book together is anything but solitary, especially when it is a book such as this.

I hope the reader will take the time to read through these acknowledgments and not just pass them by in search of the main content, because that content just wouldn’t be there if it wasn’t for a significant number of people. I cannot list them all here, as there are too many of them, but you know who you are, and I thank sincerely every one of you.

I must start with Trudy, my long-suffering wife who not only has had to put up the silence behind my concentration, but also the breaks in the silence as I eagerly expect her to be as excited as I am about a new snippet of information…. Knowing you are in my eyeline when I turn my chair means everything. I thank you for that as much as I thank you for your patience and understanding.

Even though I have been requested not to name individuals, I have to thank Daimler AG for their support and information, which has been so freely given by everyone I met. My time at Untertürkheim and Sindelfingen has been invaluable.

My sincere thanks to everyone at the Daimler archives for your hard work, patience, support and permissions. If it wasn’t for you all, this just would not have been possible.

To Harald Leschke, to Stephen Ferrada, to Harry Neimann, to Paul Bracq, a special thank you to you all for donating your precious time and insight, for answering my rambling emails, and for allowing me to use your personal images.

Herr Sacco, I am honoured; thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Nik GreeneNovember 2019

MILESTONES OF MERCEDES - BENZ DESIGN

1886

Carl Benz presents the world's first car in the form of his patented ‘motor vehicle for operation by gas engine’. The structure of the three-wheeler, which is inspired by the design of a bicycle, is an expression of engineering in its purest form.

1901

The Mercedes 35 HP establishes an independent form for the automobile and is regarded as the first modern car. The honeycomb radiator, which is organically integrated into the front of the vehicle, becomes a hallmark of the brand.

1905

The Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft in Untertürkheim sets up its own body-manufacturing shop.

The first building on the new factory grounds of the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft in Untertürkheim was the manufacturing centre. Offices were located in the front section of the building. (Photo taken around 1905.)

1909

The famous Blitzen-Benz record-breaker and racing car is the first vehicle on which the design is clearly influenced by aerodynamic considerations.

1910

A defining point is reached in the development of automotive design: a bulge below the windscreen, referred to as a ‘cowl’ or ‘torpedo’, links the chassis and engine box assembly with the body and passenger compartment to form an organic whole. With its new, smooth walls and continuous beltline, the automobile now has a harmonious form.

A worker constructing a flat-plan crankshaft in the engine manufacturing building.

The 1910 automobile, with its newly harmonious form.

1911

In parallel with the flat honeycomb radiator, DMG develops a second characteristic radiator form: the pointed version is used principally for the sporty and high-power models in the range.

1920

The DMG factory in Sindelfingen starts manufacturing Mercedes bodies.

1932

Hermann Ahrens takes charge of the special vehicles department at the Mercedes-Benz Sindelfingen plant.

Sindelfingen carpentry workshop creating body shells.

1934

With the elegant, flowing lines of its Hermann Ahrensdesigned body, the Type 500K and its 1936 successor, the 540K, represent highlights of Mercedes-Benz design, especially in the Special Roadster version, which is regarded as the ultimate dream car of the 1930s. The coupé variant establishes the modern coupé tradition at Mercedes-Benz.

1953

The Type 180, with its integral body structure, is the model which brings the classic Mercedes-Benz design into the modern era. The wings and headlamps are fully integrated into the main body, which also encloses the engine compartment and the luggage compartment at the rear. Above this rises the passenger compartment, which has a window area that is large by the standards of the day.

1954

The legendary 300 SL is introduced, with gullwing doors, new, unconventional proportions. Also new is a flat version of the Mercedes-Benz radiator grille, which becomes a defining feature of the front design of the SL sports cars. This super sports car is the last word in automotive design in its day.

W198 300 SL roadster showing the front headlights.

1957

The vertical headlamps with integral indicators introduced in the 300 SL Roadster become a defining stylistic device, which features in the front design of Mercedes-Benz passenger cars until the beginning of the 1970s.

With its clear, geometric lines, the Mercedes-Benz 600 set new standards for the class of exclusive and luxurious prestige vehicles.

1959

The Mercedes-Benz 220, 220 S and 220 SE six-cylinder saloons make their debut, with restrained tailfins that are officially described as ‘guide bars’. The tailfin Mercedes is also the world's first vehicle with a rigid occupant compartment and energy-absorbing crumple zones – attributes which mark the beginning of a new chapter in the field of safety technology.

1961

The two-door coupé variant of the 220 SE has its own distinctive design treatment, a notable characteristic being the absence of the saloon model's tailfins. The clean lines of the timelessly beautiful coupé dominate Mercedes-Benz design in the 1960s.

1963

The 230 SL appears with surprising new proportions and lines – as well as the unmistakable ‘Pagoda’ roof, a removable hard top whose special form not only looks good but also offers greater rigidity and, therefore, safety.

1971

The new 350 SL sports-car model and the S-Class of 1972 give visible and tangible expression to the integrated safety concept and define the look of Mercedes-Benz passenger cars. Important design elements are the generously sized horizontal headlamps, the indicators, which can be seen clearly both from the front and the side, the ribbed taillights and the reach-through door handles.

1975

Bruno Sacco succeeds Friedrich Geiger as head of the styling department and thus becomes the new head of design at Mercedes-Benz.

1979

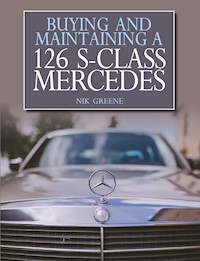

The design of the new S-Class combines traditional elements with new forms that have been developed as part of the aerodynamic optimization process. Defining features include the rising beltline, the integral bumpers and the tapering rear section.

The 126 S-Class created a new view of refinement and responsible engineering.

1982

Mercedes-Benz presents the 190 and 190 E models. The design of the new compact series, which is the forerunner of today’s C-Class, represents the consistent continuation of the principles that shaped the S-Class. The rear rises noticeably above the lower beltline of the body. It is a design choice that is initially regarded as somewhat controversial by the public, but is subsequently recognized as a timeless defining feature.

1984

The new W124 medium-size model series has a boot lid with an almost V-shaped rear face, which makes for a low loading sill while maintaining a high-level aerodynamic spoiler lip.

1991

With the new S-Class, Mercedes-Benz also presents a new interpretation of the radiator grille – the defining element of the brand.

The W201 190: the new ‘Baby Benz’.

The V-shape is framed by the taillights and is later picked up by other model series and successor generations as a characteristic styling element.

The new W140 S-Class model has an integrated radiator that is incorporated in the bonnet.

1993

As part of the first major product initiative, the Mercedes-Benz coupé study causes a stir at the Geneva Motor Show. For the first time, Mercedes-Benz presents the C-Class, the successor to the compact class, in four different design and equipment lines. The interior design plays an especially important role in expressing the particular character of the chosen variant.

The coupé study for the new C-Class.

The first showing of a completely new interpretation of the Mercedes face with four elliptical headlamps.

The compact saloon to replace the 201 C-Class.

C-Class interior options add to the sense of integration.

The Designo range of leathers.

The new E-Class Mercedes advertisements referencing the new headlamp style: ‘Seeing the Mercedes with new eyes.’

The new W220 S-Class heralded a new elongated style.

1995

The new E-Class is the first series production model with the ground-breaking twin-headlamp face. The new type of front-end design is also adopted in other model series.

The Designo range offers Mercedes-Benz customers with particularly discerning taste countless possibilities for combining exceptional paint finishes, extra-soft leather in exclusive colours and trim elements with surface finishes in fine wood, piano lacquer, stone and leather.

1996/1997

The Mercedes-Benz product initiative sees the advent of numerous new model series, such as the SLK, the CLK, the A-Class and the M-Class. Mercedes-Benz develops innovative design solutions for these fundamentally new vehicle concepts.

1998

The elongated, coupé-like profile of the new S-Class symbolizes the new forward-looking brand image of Mercedes-Benz. New standards are also set by the interior design, which harmonizes perfectly with the sportily elegant lines of the body. It exudes a strong sense of character, lightness and luxury. The side indicators, which have been moved into the mirror housings for the first time, become a defining styling feature.

1999

Professor Peter Pfeiffer succeeds Bruno Sacco as head of design.

Peter Pfeiffer takes over from Bruno Sacco as chief of design.

CHAPTER ONE

THE EARLY DAYS OF AUTOMOBILE DESIGN

FROM THE CARRIAGE TO THE FIRST PROPER CAR

In the mid- to late nineteenth century, as industrialization gradually took hold in Europe and north America, huge leaps forward in technology began to spill over into public and domestic life. Engineers, scientists, inventors and mathematicians were changing the face of society and, with the development of steam-powered engines, the world was opening up as never before.

Although vast stretches of railway were being built in earnest across the western world, many people (at least, those who could afford it) still travelled by carriage, pulled by horses or oxen on roads that were both made and unmade, many following ancient paths. It is hardly surprising that, in the early days of the automobile, many of the first ‘cars’ were built in the tradition of the horse-drawn carriage. It was the only design there was, after all.

For their first car, in 1886, Gottlieb Daimler and his chief designer Wilhelm Maybach mounted an engine into a modified carriage. The standing power unit protruded through the floor of the vehicle in front of the rear seats. A couple of years later, Carl Benz took a different design approach for his first automobile; his three-wheeler was more heavily influenced by the bicycle, with a horizontal single-cylinder engine mounted at the rear.

Daimler and Maybach quickly followed Benz in finding their own design style. In 1889, they presented their elegant two-cylinder wire-wheeled car with tubular frame, which also unmistakably borrowed design elements from bicycle manufacture.

Although Benz and Daimler had undoubtedly taken the first significant steps into the world of automobile design, their stylistic ambitions met with limited enthusiasm initially. With most radical design innovation, it takes some time to convince enough potential customers of its attributes. For the first time, the developers of the automobile were realizing that it does not matter how innovative a design is; it is the opinion of the customer that keeps a company buoyant.

Artisan-built G. Tibert 1892 17 HP.

Lutzmann-built ‘horseless carriage’ (1895).

An unknown chain-driven carriage from 1896.

Gottlieb Daimler in the back of his first ‘motor carriage’, driven by his son Adolf.

Carl Benz two-cylinder motor car, with wire wheels, showing the innovative tubular frame.

Carl Benz patent, 2 November 1886.

In simple terms, customers in the late nineteenth century were accustomed to modes of transport looking like a carriage and this is what they expected of the new automobile. At first, both Benz and Daimler were forced to respond to the conservative thinking and returned once again to carriage design. Progress and design had to be paired with conformist thinking.

Perhaps this was no bad thing. A company chronicle produced by Benz in 1910 cited a publication on the subject that dated from the early days of the automobile:

Motor cars can follow the designs of the various customary forms of carriage. When observing the vehicle from the exterior, one notices only the absence of a drawbar and the extension of the carriage body to the rear. This lengthened carriage body serves to accommodate the driving force, the engine, whereas the drawbar is replaced by a steering stick located in front of the driver’s seat.

In order to ensure that the new motor car would appeal to potential customers, Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (Daimler Motors Company, or DMG) – the engineering company that had been founded in 1890 by Daimler and Maybach – needed to convince the public that every horse-drawn carriage could be converted to an automobile by the installation of a motorized mechanism. It was no wonder, then, that carriage design in all its diversity remained the benchmark during the early period.

On 8 March 1886, Gottlieb Daimler ordered a carriage in the ‘Americaine’ version from coachbuilder Wilhelm Wimpff & Sohn, ostensibly as a present for his wife Emma’s forthcoming birthday. It became the first commercial ‘motor carriage’, and it was exactly that – a motorized carriage. It was not until 1889 that Daimler and Maybach were able to move slightly away from conventional carriage technology, by introducing the wire wheel, a two-cylinder engine and a manual gear transmission. It was another small but significant step forward in motor vehicle design.

Daimler introduced wire wheels in 1889.

1895 belt-driven two-cylinder.

Even as late as 1897, Daimler’s belt-driven cars had remained heavily influenced by carriage design. Handcrafting still dominated and, as such, the early automobiles had no individualistic design styling. The only area where design was a factor at this stage concerned the location of the drive system, and the quest for a sensible solution to this issue would change everything. Most designers were convinced that it was preferable to install the motor behind and below the passenger area. However, when Panhard et Levassor decided to introduce a front-engined car in the early 1890s, the first design challenge (both in terms of concept and construction) arose.

Émile Levassor and René Panhard were great friends of Gottlieb Daimler, and the three engineers often shared information about updates to their vehicles. The Panhard et Levassor concept was adopted by Daimler in 1897; four years later, Carl Benz introduced his first front-engined car.

Despite this important step in functional design, the first front-engined vehicles were still closely modelled on the form of a carriage, with very high ground clearance and a stout appearance. DMG still had to learn that design needed to be more than simply led by function. It took a prototype designed by Paul Daimler (see below), the eldest son of the company founder, as well as a magazine article, to convince them. The article appeared in the Scientific American periodical in 1899 and described the Daimler ‘Phoenix’ as ‘a queer-looking thing’, with a ‘picturesque ugliness’. According to the journalist, it was to be hoped that ‘some gifted genius may soon arrive … and whip it into shape and make it a damned sight more presentable!’

1894 Panhard-Levassor front-engined motor car using a Daimler engine.

1897 ‘horseless carriage’ with optional roof covering.

1897 Daimler Vis à Vis, with a Phoenix engine in the front for the first time.

Daimler Phoenix car, 1898 –1902, with the engine at the front and a four-speed gearbox.

THE PAUL DAIMLER CAR

Paul Daimler, the eldest son of the company founder, worked in the design office of DMG from 1897 onwards. The young Daimler often considered Wilhelm Maybach’s design concepts to be in competition with their own, and was not best pleased when Daimler senior overruled him. After a few run-ins with Maybach, Paul was given his own independent design office.

Having spent his formative years around Panhard and Levassor, Paul was familiar with the compact ‘voiturettes’, which had become hugely popular in France. He sensed that it would be possible to gain access to this market segment with a modern DMG design. At the end of October 1900, he completed the drawings and passed them on to the workshop.

Although three prototypes were built, the ‘Paul Daimler Car’, as it was known internally, did not go into mass production. There was a view that it would have been too appealing, to the detriment of the Mercedes models designed by Maybach. In addition, Mercedes sales had been so successful that the DMG production lines were at full capacity. However, alongside the Maybach/Mercedes, the Paul Daimler Car had shown clearly that design was not just about function; it could also represent innovation and identity.

Daimler junior went on to develop some very good engineering strategies, especially after the death of his father. He and Maybach managed to work alongside and support one another, even under the strain of the DMG board.

The Emil Jellinek ‘first modern car’.

Paul Daimler’s car never saw production.

THE FIRST MERCEDES MODEL SERIES

The development of highly sports-oriented vehicles in the period from 1899 to 1901 resulted in significant stylistic changes. With the production of its first Mercedes, DMG succeeded in making the leap from carriage-like vehicles to the first proper car.

The idea behind the 35 HP vehicle came originally at the turn of the century from Emil Jellinek, a diplomat and businessman who was based in Nice on the French Riviera. Jellinek was DMG’s main agent and distributor in the south of France, selling their cars under his company name of ‘Mercedes’, and he would often advise DMG on what they should be producing. He had already enjoyed success with DMG cars in events at the Riviera ‘speed week’, but in 1900 he urged Wilhelm Maybach, chief designer at DMG in Bad Cannstatt, to build a new car that would be even more powerful. The first Mercedes was therefore a car designed for motorsport. Differing so radically from other automobiles of the day, and with such innovative engineering details, the 35 HP Mercedes represented a final move away from carriage design. It is regarded today as the first modern automobile.

Mercedes 35 HP designed by Emil Jellinek.

The first motor car with a honeycomb radiator was also the first with the name ‘Mercedes’ marked on it in script, in honour of Emil Jellinek’s daughter.

The honeycomb radiator, designed by Wilhelm Maybach in 1896.

One of the highlights of the car’s design was the honeycomb radiator, which was designed by Maybach and made a definite breakthrough in the solution of the cooling problem. The use of small tubes of rectangular rather than round cross-section allowed for considerably improved cooling efficiency, due to the larger surface area and the smaller gaps between the tubes. The honeycomb radiator not only paved the way functionally for the high-performance reliable automobile, but also gave the vehicle a distinctive new face.

The innovative design of the first Mercedes was subsequently used as a blueprint by other manufacturers. At the Paris Motor Show of December 1902, there were so many Mercedes imitators that the press labelled the event ‘Salon Mercedes’. They also rightly referred to the racing and sports car designed by Wilhelm Maybach as the ‘first modern car’.

The appearance and influence of the Mercedes car was described in an early DMG chronicle:

The most striking thing about the outward appearance of this car was its low and elongated design, the sharply canted steering column and typical Mercedes radiator grille. This model was responsible for revolutionizing the automotive industry in every country.

Italian automobile designer Bruno Sacco, the legendary head of styling at Daimler-Benz from the 1970s to the 1990s, saw in the 35 HP Mercedes not only a masterpiece of technical beauty, but also the basis of Mercedes-Benz design history:

The design was not only technologically thought through and stylistically unique; it also proved to be extremely successful. It laid the foundations for a new era in automotive design.

DESIGNING FOR COMFORT AND SAFETY

Having its own body design and building department provided DMG with a great business opportunity, as new ways of thinking about vehicle design developed. Other automotive manufacturers had their own chassis and engine configurations but were now commissioning DMG to build their bodies for them. As time went on, there was a growing demand for a bespoke service. Although function and innovation remained the driving forces behind design, customers also began to embrace the latest trends and the desire for fashionable features began to influence design.

Compared with the horse and cart, the automobile posed completely new challenges in terms of design. Gottlieb Daimler and Carl Benz may have invented this new mode of transport, independently of one other, in 1886, but initially they followed different paths. Benz developed a patent motor car based on a bicycle with wire wheels, while Daimler’s was a motorized carriage. However, nothing could stop the rapid progression in technology, or the rise in customer expectations, and their automobiles had to be adapted to accommodate new demands. The challenge was to achieve greater comfort and greater speeds, without endangering other road users. The feature that had to change first was the chassis.

In 1889, Wilhelm Maybach, the brilliant design engineer working alongside Daimler, developed the steel-wheeled car and, at the same time, a chassis divorced from carriage-building techniques. There were also major strides in the development of increasingly powerful engines. Vehicles became faster, but they were also heavier, posing new challenges for the chassis engineers. The design solutions included coil springs, which were installed in 1895 on the rear axle of the Daimler belt-drive car, and double-pivot steering, which was introduced by Gottlieb Daimler to solve the problem of how to pilot a four-wheeled vehicle. In 1893, Benz patented this innovative steering, which was first used on the ‘Victoria’ model.

Having come across this patent when browsing through a trade journal in 1891, Carl Benz realized its significance for automobile design. The specification that ‘the extended lines of the wheel axes must converge in the centre point of the bend’ helped him to develop double-pivot steering.

The DMG direct-drive ‘Cardan’ series.

After the turn of the century, the universal driveshaft finally took over from the chain drive. It was installed in the Benz ‘Parsifal’, which appeared in 1902 as the response to the Mercedes ‘Simplex’. The universal driveshaft required a complete modification of the rear axle. The axle gearing gained an integral differential gear, which increased the unsprung masses. As this required more rear axle damping, additional dampers were installed.

Chassis engineering received a major innovative boost in the 1930s as road surfaces improved significantly, making them better suited to faster traffic. Punctures occurred less frequently and the chassis structures were safer and more comfortable. Particularly important was the additional front-wheel brake, which appeared for the first time in Mercedes series production cars in 1921, initially in the powerful 28/95 PS sports model. From the summer of 1924, all Mercedes passenger cars were fitted with brakes on all four wheels. The invention of the shock absorber made passenger cars, which were still overwhelmingly fitted with rigid axles and leaf springs, considerably more comfortable, even if this aspect still left much to be desired, especially in the smaller and lighter vehicles.

At the 1931 Paris Motor Show, the Mercedes-Benz 170 showed off a completely novel chassis with independent axles, representing a significant milestone in the direction of ride comfort and driving safety. The front wheels of this vehicle’s four individually suspended wheels were hung with no axle from a transverse-mounted pair of leaf springs. Each of the rear wheels was suspended from a semi-swing axle whose jacket tubes were each anchored to the frame by two coil springs on the wheel side and to the differential by pivot bearings. The result was a great reduction in the proportion of unsprung masses.

The first swing axle made its appearance on the teardrop race car in 1923.

A clear view of leaf springs.

Individual wheel suspension, installed in every Mercedes-Benz passenger car since its introduction in the 170 ‘Maxime’ model, gained the company a reputation for building extraordinarily comfortable and safe vehicles.

The Mercedes-Benz 170 was followed in 1933 by the 380 model eight-cylinder compressor sports car, another vehicle with fully independent suspension, whose front wheels were suspended for the first time from parallelogram transverse control arms with coil springs. This pioneering design, which treated wheel control, suspension and damping as separate systems, became the standard front suspension, not just for Mercedes-Benz but for numerous other manufacturers throughout the world.

Independent coil springs on the rear of the 170 improved comfort and road-holding enormously.

Independent front suspension of the Mercedes-Benz 170 (W15) of 1931, with two transverse-mounted leaf springs and hydraulic shock absorbers.

After various refinements, the two-joint swing axle, as introduced in 1931 in the Type 170 model, eventually became the single-joint swing axle in 1954. It would continue unchanged as a standard Mercedes-Benz component until 1972. It, too, had thrust arms and coil springs, with an additional horizontal compensating coil spring on the more powerful models.

A new era in ride comfort was opened up by a variant introduced in 1961. Initially available with the Mercedes-Benz 300 SE, it featured air chamber spring bellows replacing the coil springs; at the same time, hydro-pneumatic self-levelling was introduced for the rear axle. This was a development from a self-levelling control system that had appeared earlier on, in 1951, on the Mercedes-Benz 300, operated via an electrically selectable torsion bar spring. The Mercedes-Benz 600 even had shock absorbers whose characteristics could be adjusted from inside the vehicle.

The next significant step was the diagonal swing axle that was introduced in 1968 in the 114/115 model series. The design was based on a semi-trailing arm axle which was also supported on coil springs, ensuring that track and, in particular, camber remained largely constant under spring compression and rebound.

The front independent suspension not only became the standard for all Mercedes but was also adopted by many other manufacturers.

Single joint swing axle from a W100 600. This set-up was used well into the 1970s.

Diagonal swing axle.

The end of 1982 saw the introduction of the Mercedes-Benz 190 in the W201 compact class series. It was the direct forerunner of the C-Class. Its unprecedented multi-link independent rear suspension was a technical sensation. The optimal travel of the independently suspended rear wheels was achieved by distributing the forces and moments to five three-dimensionally arranged links, the geometry of each being especially tailored to its function. Comfort and road-holding were optimized independently of each other. All this was complemented by an equally redesigned front suspension on transverse control arms with damper struts and separately located coil springs. The multi-link independent rear suspension was gradually introduced into the other Mercedes-Benz models.

DESIGNING FOR AESTHETICS

The second decade of the twentieth century brought with it major changes. Einstein published his general theory of relativity, the first all-metal aeroplane took to the air, as did the Zeppelin. With the Trans-Siberian Railway linking the west with Vladivostok and the Panama Canal drastically shortening the route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the world was becoming smaller.

Before the First World War, automotive design centred primarily on technology. Master bodybuilders determined the structure and lines of the first cars based on little more than functionality; the idea that the shape of a car should, could or would involve a designers or an artist never entered the mind of any manufacturer.

On the art scene, however, Futurism and, later, Aestheticism were making waves. These movements idealized technology and the artistic perspective soon had an impact on real automotive design. For example, wing designs began to be drawn to represent speed and dynamism; the wing now had an aesthetic role as well as a functional one. No longer did form simply ‘follow function’; on the contrary, many automotive companies and bodybuilders used elements that were clearly designed to arouse emotions. Pioneers such as Walter Gropius (the architect and founder of the Bauhaus movement) enthused over the beauty of the car and many proposed automotive design sketches of their own. As the body of the car began to be designed more in line with aesthetic principles, the growing number of technical designers now also became stylists. These were the people who became responsible for automotive design gradually developing what would become the typical car shape of the future.

THE BLITZEN-BENZ

For Benz & Cie, the Blitzen-Benz of 1909 became the first vehicle to embody a dynamic appearance with a cohesive design idiom. A famous racing and record-breaking machine, it became the first land-going vehicle to pass the 200km/h mark, and set a new land speed record at Daytona Beach in 1911 of 141.7mph.

The Blitzen-Benz was the first vehicle to be designed taking aerodynamic considerations specifically into account. Although aerodynamics had no very significant role to play for the road vehicles at the time, the Blitzen-Benz set new standards in the evolution of the automobile. Rather than being separated from the body at the firewall, the chassis with the engine and front structure were integrated with it in a formal unit. This design feature began to be adopted on passenger cars, although this change occurred gradually, because of the greater width of the body of the vehicles. The ‘torpedo’ became a defining design feature. Also referred to as a ‘cowl’, the bulge below the windscreen provided a formal link between the engine box and the body.

The new flat sidewalls and continuous waistline meant that the separate entities of chassis, engine housing and body began to be fused into one organic unit, presenting a new challenge for body design.

The Blitzen-Benz, with its teardrop aerodynamics.

It was on the Blitzen-Benz that body design became one fluid unit for the first time.

Expressing Brand Value

In subsequent years, the lines of Mercedes-Benz automobiles continued to capture the imagination of the public. Their innovative approach was seen to reflect both the philosophy and the status of the brand. It was design that raised awareness of the product while also expressing the brand values.

A DMG chronicle made the following observations during this period:

The boom in German industry and German trade brought money into the country and this money changed hands briskly. The hard-working business ethic brought a prosperity that manifested itself in a certain desire for luxury.