35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

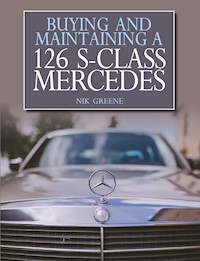

The Mercedes 126 S-Class of 1979-1991 remains the most successful premium saloon in the company's history and is considered by many to be one of the best cars in the world. "You don't simply decide to buy an S-Class: it comes to you when fate has ordained that your life should take that course. The door closes with a reassuring clunk - and you have arrived," said the sales brochure of the first real Sonderklasse, the W116. With over 300 colour photos and production histories and specifications for both Generation One and Two models, this is an essential resource for anyone with an interest in this timeless car. The book covers an overview of the key personalities who drove the development of this model; the initial 116 Sonderklasse and its subsequent evolution; the history and personality of each model and finally detailed analysis of the different engines - both petrol and diesel. This essential resource explores both the technical and social sides of how this legend was born and is superbly illustrated with 314 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Mercedes-Benz

W126 S-CLASS1979-1991

Nik Greene

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Nicholas Greene 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 542 8

Acknowledgements

The job of a writer is more often than not solitary, sitting at a screen, losing oneself in content. This often spills over into relaxation and sleep time when words, ideas, images and research get mulled over, cogitated and sometimes involuntarily spoken aloud in the small early hours. Not once did my wife Trudy complain at the loss of company or the glazed look she received upon my realization that she was actually talking to me. I thank her sincerely for her support from beginning to end.

I would like to thank all at The Crowood Press for once again having the faith in my enthusiasm for the 126.

I must give a massive thank you to those at the Daimler Archives in Stuttgart for the time, dedication and continued enthusiasm they have showed me. The Daimler Classic archives resource is an incredible place to be for an enthusiast, and never once did they take that for granted.

My special thanks go to my patient, enthusiastic friend, Bert van de Bovenkamp, who accompanied me without complaint on every research trip to Stuttgart, aided me with the German language and drove me around for no other reason than being supportive and sharing in my enthusiasm for the 126 and German beer; a true friend.

I would like to thank Ralf Weber for the photos of his beautiful 560SEL Station wagon, but more importantly for the assistance he gave with the introduction to and during the interview with Bruno Sacco; not only a Mercedes enthusiast to the core, but a rare philanthropist of his knowledge.

I wish to sincerely thank Bruno Sacco for not just agreeing to be interviewed by me but for really spending quality time with me. It was a day I shall remember fondly for as long as I live.

Thank you to all those who assisted me with photos and enthusiasm, especially: Bram Corts, author of the website resource www.1000sel.com; Allen Kroliczek for his beautiful AMG Engine pictures; and of course Philip and Les Kruger for the stunning photos of their ‘limited edition’ South African-built 126. Hopefully seeing your ‘pride and joy’ on the front cover will give you joy also.

CONTENTS

Introduction: ‘The Best or Nothing’

CHAPTER 1FROM ‘S’ TO ‘SPECIAL’

CHAPTER 2ALL THINGS TO EVERYONE

CHAPTER 3CONCEPTION TO FRUITION

CHAPTER 4PRODUCTION

CHAPTER 5THE MODELS

CHAPTER 6THE POWER UNITS

CHAPTER 7SPECIAL AND BESPOKE

Appendix ISpecifications: Generation One Saloon

Appendix IISpecifications: Generation One Coupé

Appendix IIIGeneration One Sales Per Year

Appendix IVSpecifications: Generation Two Saloon

Appendix VSpecifications: Generation Two Coupé

Appendix VIGeneration Two Sales Per Year

Index

INTRODUCTION: ‘THE BEST OR NOTHING’

When writing a book such as this, the common practice is to write an introductory biography about the company itself; however, not wanting to make light of the contribution made by Gottlieb Daimler, Wilhelm Maybach and Karl Benz as the founders, what really set Mercedes-Benz, and latterly Daimler AG, apart as a company was not only the vision and ethic that they brought with them as individuals, but the fact they were willing to recognize the talent and abilities in others – never more so than in those early days, when the ‘horseless carriage’ transitioned into the motor car. A dizzying number of inventions from an equally dizzying number of inventors rushed to make a name for themselves and instead of competing against them, Daimler quickly realized that quality over quantity was what would really raise them above the rest and consequently ‘cherry picked’ these talented people.

Gottlieb Daimler’s motto, ‘Das Beste oder nichts’ (‘Nothing but the best’) was as much about the company as it was the product.

The story of Emil Jellinek giving the name of his daughter Mércédès Jellinek, to his line of racing engines and eventually, after merging with Daimler to become Daimler-Benz, giving the Mercedes name to the vehicles produced thereafter, is a story well told and, although this is of great importance to the company history, what is doubly important is the man himself. Apart from being a perfectionist, he expected nothing less from anyone else. His fiery temper and a willingness to speak his mind raised a few hackles at DMG (Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft), especially Gottlieb himself. ‘Your engineers should be locked up in an insane asylum’ and ‘Your car is the chrysalis and I want the butterfly’, were just two documented harangues.

Emil Jellinek. BARON HENRI ROTHSCHILD

Wilhelm Maybach, on the other hand, knew exactly where he was coming from; he could already see that the only thing holding back the development of better, faster and more efficient engines was the vehicle itself. They understood that making a better vehicle meant making it more capable of being better; the ‘horseless carriage’ could never progress without addressing stability and safety.

Emil Jellinek and his chauffeur Hermann Braun in Baden near Vienna. First Daimler vehicle (6-hp ‘Double Phaeton’ model) from 1898, which Emil Jellinek had purchased in Cannstatt.

Emil Jellinek summed up what Daimler-Mercedes would become when he said, ‘I don’t want a car for today or tomorrow, it will be the car for the day after tomorrow’.

It is all too easy to look at big companies such as Daimler AG and just see a large, faceless corporation, and you may feel these early pioneers are a million miles from what has become the Daimler AG of today, but you would be wrong – these people were just the beginning of a string of individuals who ‘stuck to their guns’ and kept the integrity of their design intact. It is these individuals who would mould the company into what it is today.

The small ‘bio’ will give the reader some idea of the talent involved in creating every vehicle in the Daimler/Benz/Mercedes range, and on reading through the content of this book, hopefully it will bring alive the individuals, as opposed to just being faceless names.

WERNER BREITSCHWERDT (BORN 23 SEPTEMBER 1927)

Having been drafted to the eastern front at the age of sixteen, Werner Breitschwerdt’s electrical engineering apprenticeship at the Technical University of Stuttgart had to be put on hold until his return and release from active duty and, even though he did everything in his power to ‘catch up’, it still put him back a couple of years by normal standards. After achieving physics to undergraduate level and gaining his diploma in electrical engineering, he continued to work at the same university as scientific assistant.

After joining Daimler-Benz AG in April of 1953 he was put in charge of a team to develop the industry’s first CAD (computer-aided design) system and quickly made a name for himself as a very capable street-smart engineer; he was eventually asked to join the passenger car body division as experimental engineer.

Although not everyone took to his hands-on, outside-of-the-box, perfectionist way of working, within twenty years he was appointed director and head of development for this section, with styling (as the design division was then known) being added to his responsibilities one year later.

Barényi (second from the left), Häcker (third from the left), Wilfert (third from the right) and Professor Breitschwerdt (far right) explaining the constructive details, 1960.

Professor Dr Werner Breitschwerdt.

In 1977, Breitschwerdt joined the board of management of Daimler-Benz AG as a deputy member before being appointed a full member in 1979. In this capacity, he was once again responsible for research and development. Under his stewardship, he oversaw the development of the C111 range of research and experimental vehicles, which became a test bed for all future technologies that would play a definitive role in shaping the vision of accident-free driving by way of electronic assistance systems, alternative drive concepts and multilink suspension set-ups.

One particular milestone was the electronics side of the ABS anti-lock braking system alongside Professor Guntram Huber, which celebrated its worldwide series premiere in the S-Class (W 116) in 1978.

What Breitschwerdt’s hands-on dogged pursuit of vehicle and occupant safety in all vehicles proved to Daimler was that it didn’t have to be at the expense of their usual standards of quality, robustness, dynamic attributes and sporting elegance, and this went on to stand them in good stead as they entered a large, medium-range car segment that has continued today in the C Class range.

From 1983 until 1987, Breitschwerdt was chairman of the board of management and CEO of Daimler-Benz AG, and during this time he initiated a joint research project called PROMETHEUS (Programme for European Traffic with Highest Efficiency and Unprecedented Safety). The result was the advancement of numerous technologies offering huge leaps forward in safety. At Mercedes-Benz, these were translated into specific technical products such as the DISTRONIC PLUS cruise control system and the automatic PRE-SAFE® brake system, which we now take for granted.

Although Breitschwerdt’s manner and appearance made him an easy mark for detractors who thought he should be a little more polished, his achievements spoke for themselves. He summed himself up succinctly when he said, ‘Top management should be able to create the right motivation that gets more ideas out of the organization than the company can use’.

He has been, and he was, the recipient of numerous awards culminating in receiving the ‘Grand Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany’ and being inducted into the European Automotive Hall of Fame, Geneva, in 2009.

Mercedes-Benz record car C 111/III, 5-cylinder turbo-diesel in trial and record runs on the circuit in Nardo, April 1978. Standing in front of the record car, and sitting from left to right: driver Paul Frère (blue driver suit), driver Guido Moch, Professor Werner Breitschwerdt, Professor Hans Scherenberg, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, driver Rico Steinmann, driver Dr Hans Liebold, Friedrich van Winsen and Günther Molter.

BÉLA VIKTOR KARL BARÉNYI (BORN 1 MARCH 1907)

Bela Barényi started life in Hirtenberg near Vienna. Being born into one of the wealthiest Austrian families in Austria–Hungary afforded him the privilege of witnessing, first hand, the early transitional growth of the automobile in a world of horse-drawn carriages, as his father owned an ‘Austro-Daimler’ motor car. Little did Bela Barényi know that it would be this very automobile that would not only shape ‘his’ future, but that of the automotive world also.

After his father was killed in action in the First World War, the following ‘Great Depression’ quickly brought the family business to financial ruin and great hardship ensued. Having little money to afford to pay his school fees, he had to rethink his future. It was only the fond memories of that first automobile that spurred him on to fight tooth and nail to find the means to enrol as an engineering student at the Viennese Technical College of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering.

As a young student he quickly developed an amazing ‘vision’ of design and problem-solving, which focused his attention not on current models and thinking, but of potential future enhancements. Within a year he had sketched his ideas of a future ‘people’s car’.

Barényi called his design for a people’s car a Volks-wagen. This would become very significant twenty years later.

Early sketch, explaining the concept of crumple zones.

More struggling was yet to come; he graduated with excellent marks in 1926 just as the Great Depression was starting to bite. His aim was always to get into DMG (Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft) and, even though they had merged with Benz & Cie, the current economic climate had put a hold on recruitment.

It took almost a decade of surviving on temporary posts and a freelance draughtsmanship before finding himself a steady job at Gesellschaft für technischen Fortschritt (GETEFO, Society for Technical Progress) in Berlin; but, once again, at the beginning of 1939 he was made redundant.

Again he applied to what had now become Mercedes-Benz but was turned down. With nothing to lose, he approached Chairman Wilhelm Haspel directly and demanded a face to face interview to show him his abilities. His tenacity and determination won him over; Haspel recognized immediately his passion, not just for the motor car, but safety, ‘You, Herr Barényi are twenty years ahead of your time, you will be put under a bell-jar at Sindelfingen and everything you invent will go directly to the patent department’. Barényi never had to fill out another job application again.

The first Mercedes-Benz vehicle with bodywork developed according to this patent was the 1959 W 111 series – better known as the ‘Tailfin Mercedes’.

Particularly in the ‘post-war era’, no one really wanted to be reminded of the dangers of driving and, in essence, the topic was thought to be a sales killer; but, again, Barényi’s passion forged onward. His biggest breakthrough came on the 23 January 1951 when he registered patent DBP 854.157 with the description, ‘Motor vehicles especially for the transportation of people’; behind this austere description was no less than the description commonly referred to as the ‘crumple zone’.

Béla Barényi was the first to recognize years before, in fact, that kinetic energy should be dissipated by deformation so as not to harm the occupants of the vehicle.

All in all, this discovery was to revolutionize the entire automotive industry and became the decisive factor in ‘passive safety’. The ingenious mastermind of the idea knew that, contrary to the popular belief that ‘a safe car must not yield but be stable’, in a collision, kinetic energy must be absorbed through deformation in order for the occupants to be protected. He logically split the car body into three ‘boxes’: a soft front section, a rigid passenger cell and a soft rear section. The patent was granted on 28 August 1952.

Being an inventor through and through, and not one to rest on his laurels, Béla Barényi’s considerations under the engine hood were equally revolutionary: the steering gear moved far to the rear and the auxiliary units were arranged in such a way so as not to form blocks with each other in the event of a collision, but rather to slip past one another, permitting more effective crumpling of the bodywork.

The interior of the W 111 didn’t escape his touch either: for the first time ever in any automobile, the interior was completely redesigned so as to reduce further injury hazard in an accident. Hard or sharp-edged controls were replaced by yielding, rounded or recessed units, combined with recessed door handles, a dashboard that yielded on impact, padded window ledges, window winders, armrests and sun visors, and a steering wheel that featured a large, padded boss. Under heavy impact, the rear-view mirror was released from its bracket. In 1961, anchorage points for seat belts were fitted as standard in the ‘tail fin’. Lap belts were available from 1957 and the first diagonal shoulder belts appeared in 1962. Round-shoulder tyres also made their debut on this car.

More than 2,500 patents originated from him. Some of them have saved thousands of lives and still set the automotive standard today. He became known as ‘The Life Saver’.

What of the sketch of the ‘people’s car’? Well, in a legal battle that lasted three years, he finally won his claim that the drafts he had made of the ‘future people’s car’ as a student be recognized as the ‘intellectual parent’ of what became the Volkswagen Beetle.

In 1972 Barényi retired – but he was never forgotten. In 1994, he was received into the ‘Automotive Hall of Fame’ in Detroit and welcomed into the circle of outstanding inventors and innovators. He died in Böblingen near Stuttgart in 1997.

Since 2005, the Béla Barényi Prize is awarded in Vienna to people who have made outstanding achievements in the field of traffic and automotive transport.

Béla Barényi.

In 1967, Béla Barényi received the Rudolf Diesel Gold Medal from the German Inventors’ Association.

FRIEDRICH GEIGER (BORN 24 NOVEMBER 1907)

Freidrich Geiger was born in Süben in the south of Germany. He originally trained as a cartwright; however, his artistic nature soon drew him away from coach building and closer to coach and cart design. Although somewhat unusual for the time, he decided to give up his work as a cartwright to go to university to formally study as a design engineer. In hindsight, this turned out to be a logical and consistent career path, as, on graduation, he was lucky enough to fall straight into a position at the ‘special coach-building department’ at the Sindelfingen factory of Daimler-Benz AG, led by Hermann Ahrens.

Geiger was able to convincingly demonstrate his double talents as a hands-on engineer and a person with a sense of aesthetics and proportion, and he was given a free hand to put this into practice when customers would request oneoff creations to fit to a factory-made chassis. These models became known as ‘Sindelfingen Coachwork’. Geiger’s own stunningly beautiful Mercedes 500K (W 29) was one of his first full designs.

The stresses and losses of the Second World War seemed to break his spirit, so around April 1948 he decided to take a sabbatical to find his passion once more. In a very short while he had rekindled his love for watercolour painting and became a very accomplished artist.

Around June 1950, Karl Wilfert welcomed him back with open arms as a test engineer to the newly created styling department in Sindelfingen and within a couple of years he had been appointed head.

His quiet and unassuming manner, coupled with his iron discipline and rigour, would often be mistaken as aloof arrogance and this made him reticent to put himself in the limelight, so he relied heavily upon his team, not just a stylists but as his mouthpiece.

To mark the designer’s 100th anniversary, Günter Engelen summed him up in one sentence when he wrote: ‘Friedrich Geiger was rather the type of reticent conductor who was capable of bringing out the very best from his chamber orchestra without being overly ostentatious.’

On 1 October 1969, Geiger was appointed senior manager within the styling directorate and there he remained until his retirement on 31 December 1973. Alongside designers such as Paul Bracq and Bruno Sacco he left behind a legacy of numerous outstanding saloons, coupés, convertibles and roadsters for Mercedes-Benz.

The range of model series for which he was responsible includes the Fintail cars (W 110 and W 111/112), the Pagoda (SL from the W 113 series) and the representative Mercedes-Benz 600 (W 100). These were followed by the luxury-class models from the W 108/109 and W 116 series, the SL (R 107) launched in 1971 and the famous cars from the mid-sized series W 114/115 and W 123.

His legacy of design integrity lived on in a long line of automotive designers. Bruno Sacco said of him, ‘He created timeless designs.’

Friedrich Geiger (with a white coat) usually stayed in the background. Here (from left to right) with Karl Wilfert, Fritz Nallinger and Paul Bracq.

Sketches of the the 190 SL and 300 SL.

Friedrich Geiger.

Professor Guntram Huber joined the Daimler-Benz AG in 1959 as an experimental engineer and, in 1971, became head of department for the development of passenger car bodies. From 1977 until his retirement in 1997, Professor Huber headed this area as director.

GUNTRAM HUBER (BORN 20 MARCH 1935)

Having completed his formal education at a Landshut secondary school that specialized in classical studies, Guntram Huber went on to graduate with a degree in mechanical engineering at the Technical University in Munich.

Upon walking into a job at Daimler-Benz AG in 1959 as a test engineer in the Engineering Department for Passenger Car Bodies, he was thrown in at the deep-end, working alongside Daimler-Benz’s safety guru Béla Barényi with what was referred to as the new ‘shape-stable occupant cell and crumple zone’ for the W 111 (commonly called the Heckflosse or Fintail). Although it was almost ready for production, proper verification crash tests were yet to have been carried out, so the young engineer became personally involved in the early crash test methods, using winches and steam-powered rockets.

Huber had found his niche and over the years became a fervent promoter and constant proponent of advances in active and passive safety measures, to the point of encouraging Daimler AG to custom-design a new indoor crash test hall at Sindelfingen.

By 1971, he had been promoted director of development passenger car bodies and in March 1977, Huber succeeded Werner Breitschwerdt as head of engineering for passenger car bodies. During his tenure, numerous safety innovations developed under his direction made their way into the new range of S-Class vehicles. Major milestones such as the ABS system, which Mercedes-Benz presented as a world first in the 116 model series in August 1978, continuing with the first passenger car in the world systematically developed to meet the safety requirements for an offset crash and after fifteen years of groundwork and development Mercedes-Benz became the first automotive brand to offer customers a driver’s airbag in the steering wheel – for which Huber became known as the ‘father of the airbag’. It was followed in 1988 by the front-passenger airbag, installed first in the S-Class 126 of 1979.

In 1981, on top of his work for Mercedes-Benz, he accepted a post as a lecturer in body-shell engineering within the motor vehicle engineering department of the Technical University of Darmstadt. He was appointed an Honorary Professor in 1987. He remained Chair of the department until July 1998 – having already retired from his post as a development engineer on 31 December 1997.

Still today, he considers the Mercedes-Benz brand’s greatest service to be that it raised public awareness of the issue of vehicle safety through countless innovations and made it the norm. Indeed, many Mercedes-Benz inventions are now standard equipment in production vehicles across the globe.

Bruno Sacco discussing the C 111 project with Peter Pfeiffer.

BRUNO SACCO (BORN: 12 NOVEMBER 1933)

Bruno Sacco was born in the north-eastern Italian city of Udine close to the Slovenian border. In 1951, he passed his exams as the youngest surveyor in Italy. During a visit to the Turin motor show, his fascination for vehicle design was piqued after catching a glimpse of the French designer Raymound Loewy’s Studebaker Starlight Coupé. ‘The car took my breath away, it was like a moving sculpture from another world,’ Bruno Sacco recalled many years later. It was not until he chanced upon the same car a little later in Tarvis, where he was living with his family, that his resolve to pursue a career in design manifested itself in earnest. To what seemed like a whim to others, he moved his family 600km north-west to Turin, the spiritual home of modern designers such as Pinin-Farina, Nuccio Bertone, Gigi Michelotti and Carozzeria Ghia, to most of whom he would become a frequent visitor.

His experience in automotive design grew exponentially after managing to procure contract work with such greats as Giovanni Savonuzzi and Sergio Sartorelli at Ghia and his reputation soon came to the attention of head of testing for car bodywork and styling at Mercedes-Benz, Karl Wilfert.

Having already managed to hone his German language skills while working on the Karmann-Ghia, he agreed to a meeting and on 13 January 1958 he took up his work at Daimler-Benz in Sindelfingen as second stylist, after Paul Bracq. Looking back on his career, Bruno Sacco once said, ‘All I knew was I wanted to amass as much experience of different types of design as possible, France, Germany and the USA. However it turned out completely differently.’ This was to be Sacco’s job for the next forty-one years.

Béla Barényi in the office with the team of the Department of Advanced Engineering. People from the left: Hermann Renner, Gerhard Busch, Béla Barényi, Heinrich Haselmann, Gustav Reichstetter and Bruno Sacco, around 1970.

Bruno Sacco was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame (Dearborn, Michigan) on 3 October 2006.

In less than ten years with Daimler-Benz, Sacco was promoted into management and placed in charge of the bodywork and ergonomics department. With no formal written rules on design, he decided that the way forward was to, first, understand the Benz culture. ‘Nothing but the best’, painted on a dusty board in the factory, was where he started. ‘Once I understood it, I began to evolve the form.’

As stylist and designer he was involved in various projects under the supervision of Karl Wilfert, Friedrich Geiger and Béla Barényi , including the Mercedes-Benz 600 and the 230 SL roadsters. In addition, he was made project leader for the design of the safety exhibitions of the day, as well as the so-called ‘test labs on wheels’, the C 111-I and C 111-II experimental vehicles. In 1970, Sacco became head of the body design and dimensional drawing department at Daimler-Benz. Under his aegis, this period saw the development of the ESF (experimental safety vehicle) prototypes and the 123 series.

In 1975, and now bearing the title senior engineer, Bruno Sacco took over as successor to Friedrich Geiger as head of the styling department and from then on played a vital part in shaping the overall appearance of Mercedes-Benz passenger cars. The key stages of this gradual formal evolution were the record-breaking C 111-III diesel (1978) and the W 126-series S-Class (1979). In 1978, Sacco was appointed head of the styling department.

In 1987, the board of management appointed him director of the design department, and in 1993, in his function as head of design, he became a member of the company’s board of directors. In this capacity Bruno Sacco also assumed a mandated role for the design of products for the commercial vehicle division. In March 1999, after forty-one years’ service with Mercedes-Benz design, Bruno Sacco handed over leadership of the department to Peter Pfeiffer.

Homogenous Affinity

From early on in his learning period, Bruno Sacco saw how designers at Mercedes-Benz had succumbed to the magical pull of a fashion trend. He noted that the Mercedes-Benz W 111 series saloons, introduced in 1959, were a prime example. Similar to virtually every other European and North American manufacturer, they sported ‘tailfins’ and as quickly as they arrived, they were abandoned with equal alacrity.

The tailfin models from the upper category were superseded in 1965 by the Mercedes-Benz 250 S, 250 SE, 300 SEb and long-wheelbase 300 SE models from the W 108 and W 109 series. These vehicles signalled the beginning of a new era: design without any fads of fashion, stating its point through simple elegance.

He said ‘I am a designer at Mercedes-Benz not because I think “art for the sake of art” should be my motto, but because I want the cars for which I am responsible to sell successfully’. What he actually managed to do was to create a new design language. Something later referred to as ‘homogenous affinity’.

The first law of this philosophy was what he referred to as the ‘vertical affinity’: ‘A Mercedes-Benz must always look and feel like a Mercedes-Benz.’ It became the central pillar of the Mercedes-Benz design philosophy and ensured that a predecessor model did not appear outmoded following the presentation of a new model generation. The goal of this strategy was to retain the positive aura of a Mercedes-Benz on the roads by members of the public representing different cultures from all over the world, for as long as possible, and to this end, while most designers think ten years ahead, Sacco challenged his designers to think thirty years ahead.

The second main pillar of the Mercedes-Benz design philosophy was brand identity. This called for traditional design characteristics to be maintained, which would be further developed and featured in all model series simultaneously. In this context, the term Sacco used was ‘horizontal affinity’, recognizable by body accents, for example, in the design of the radiator grille, headlamps and tail-lights. Although there were formal differences in detail between saloons, coupés and roadsters, the family likeness remained obvious to even the most casual observer at first glance.

BRUNO SACCO AWARDS

During the years he worked at Daimler-Benz, Bruno Sacco received numerous personal awards:

1981: Honorary member of the Academia Mexicana de Diseño

1991: Received the title Grande Ufficiale dell’Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana

1993: Winner of the Cover Award – Auto & Design, Turin

1993: Awarded the Premio Mexico 1994 – Patronato Nacional de las Asociaciones de Diseño AC, Mexico

1994: Winner of the Apulia Award for Professional Achievement

1996: Voted Best Designer by Car magazine

1996: Voted Designers’ Designer by Car magazine

1997: Winner of the Lifetime Design Achievement Award, Detroit

1997: Presented with the Raymond Loewy Designer Award by the Lucky Strike brand

2002: Honorary doctorate from the Udine University, Italy

2006: Inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame, Dearborn

2007: Inducted into the European Automotive Hall of Fame, Geneva

CHAPTER ONE

FROM ‘S’ TO ‘SPECIAL’

‘You don’t simply decide to buy an S-Class: it comes to you when fate has ordained that your life should take that course. The door closes with a reassuring clunk – and you have arrived’, so said the sales brochure of the first real Sonderklasse, the W 116.

Through almost sixty years of just being ‘Sonder’, the Mercedes-Benz ‘S’ now has a class of its own and has since become the ultimate reward for a lifestyle shaped by mobility, individuality, success and sophistication, and what has made the car and its predecessors unique among the world’s great saloons.

The tradition of using the nomenclature ‘S’ for the Mercedes-Benz did not just begin with the type 220 (W 187) in 1951; its roots can be traced right back to the very origins of the Mercedes’ brand itself, at the start of the twentieth century, indicating a high-end ‘Saloon’.

An early, eye-catching example of this is the Mercedes-Simplex 60 PS launched in 1903. This elegant and luxurious touring saloon was once owned by Emil Jellinek, a key protagonist in the early history of the Mercedes’ brand. The then top-of-the-range model is now one of the most spectacular exhibits in the Mercedes-Benz Classic collection

In the years to follow, the Mercedes and Benz sales’ ranges always included several high-end, luxury ‘saloons’, even though open-top tourers were by far the most commonly used body form during this period. The more powerful models were also offered as luxury ‘saloons’ affording the ultimate in passenger comfort.

In the mid-1920s, it was a different picture. Due to ever more powerful engines and increasing volumes of traffic, which the road-building programme was unable to keep up with, safe-handling characteristics, a comfortable interior and optimum protection against wind, rain and dust, were becoming more and more important. Saloons or ‘Saloons’ and Pullman saloons gradually began to replace the open-top tourers.

These high-end saloons became a welcome addition to their range of vehicles from the high-end, luxury segment, so Mercedes-Benz started to produce them as a platform to launch their latest technological or innovative advancement.

They not only meet the highest standards in terms of safety, comfort and style: due to their status as an absolutely topof-the-range model, extremely luxurious ambience and particularly opulent and spacious interior, they are primarily tailored to meet the requirements of individuals who need to, or have to, reflect their status in the choice of their vehicle, too. This tradition follows the philosophy of a car that is always a reflection of the times. After all, with each new generation of its top-of-the-range vehicles, Mercedes-Benz has always provided convincing responses to the wishes and needs of each specific era. In a phrase that sums up the importance of the model’s history right through to the present day, the S-Class and its predecessors are, and have always been, the epitome of the perfect car. Not for nothing has the S-Class been acclaimed again and again as the best car in the world.

FROM W 191 TO ‘PONTON MERCEDES’ (1952–59)

The first time that Mercedes really admitted to using the soubriquet ‘S’ to refer to ‘Sonder’ (special) was with the release of the type 170 S (W 136), later becoming the (W 191). Even though already essentially a bespoke high-end vehicle manufacturer, they realized that there was a market to appeal directly to successful business owners and company directors.

The upgraded Type 170 S Limousine, 1949–52 (bottom). The Standard 170 D Saloon, 1949–50 (top).

Initially developed from the W 136, and looking similar, being better appointed as well as 170mm (6¾n) longer and 104mm (4in) wider, it had more in common with the Type 230 (W 153) of 1938. This in itself marked the return of Mercedes-Benz to the bespoke luxury segment; no mean feat, considering it was only six years into the first phase of Germany’s reconstruction, following the Second World War.

Following the relative success of this luxury, high-end optioned market, Mercedes decided to continue creating a ‘special’ line and the (W 191) developed into the (W 187). For the first time since before the war, this used a powerful 6-cylinder engine, the significance of which carried on to be the mainstay of the true ‘Sonderklasse’ models from the later 1970s onward.

Also, for the first time, Mercedes decided to take the model one step further and started to produce a single stand-alone luxury model to rival even the Rolls-Royce of the time, the Type 300 (W 186); it quickly found favour with business owners and statesmen alike, including that of Konrad Adenauer the Chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963, who commissioned six custom versions of the Cabriolet, Saloon and Landaulet. It became so inextricably linked with his name that to this day they are referred to as the ‘Adenauer’ .

The 1951 300 is nicknamed ‘Adenauer Mercedes’ as the first German chancellor favours this model. The design is a mixture of traditional pre-war shapes and the modern ‘pontoon’ shape. It was the largest and fastest series-produced car made in Germany. It soon became the most popular luxury car for kings, statesmen and industrial magnates.

The Mercedes-Benz 300 D (W 189) appears at the IAA International Motor Show in the autumn of 1957 as the last of the legendary 300 series.

What had become very clear was that there was a clear market for ‘special’ vehicles and Mercedes continued to build the W 186, through to 1963, albeit now called the W 189 until it was replaced by the 600 (W 100)

The Langenscheidt German–English Dictionary defines Pontonkarrosserie as ‘all-enveloping bodywork, straight-through side styling, slab-sided styling.

Even with its more integrated body style, the W 187 was beginning to look old-fashioned in comparison to the lower, wider look of other European and North American model designs; but, already, a new era of body design was well underway. The days of the old-style ladder chassis with separately mounted body parts was on its way out and the ‘self-supporting’ body was being introduced across the automotive world.

This advanced method of body mounting allowed for a much more integrated form: where hitherto large bulbous wings and running boards, for example, formed a more limited basis for shape, the ‘Ponton’ allowed more spacious interiors, lighter and more torsionally rigid bodies, which in turn improved agility and handling, as well as vastly improved aerodynamics. Out of this arose a harmonious and, by the standards of the day, generously proportioned, glazed passenger compartment.

This was now the point, according to many experts, at which automotive designers finally made the transition from styling to design.

FROM ‘FINTAIL’ TO HIGH-PERFORMANCE SALOON (1959–72)

The ‘Ponton’ body styling allowed designers to get more artistic and use a bit more flair and the ‘Fintail’ model is a case in point.

This new high-end generation represented a very special milestone in automotive history: it was the first time that the ‘self-supporting’ body shell, incorporating the safety cell and crumple zones devised by Béla Barényi, had been used on a series production car. Introduced in 1959 (220, 220 S and 220 SE (W 111)) they earned their nickname from the understated tailfins that adorned the rear wing. Not wanting them to be considered merely as a fashion accessory, they were officially known as ‘sight lines’ or ‘guide fins’, since they fulfilled a genuinely useful function for parking manoeuvres.

Nevertheless, these visual style elements were highly controversial. The later head of design, Bruno Sacco, even thought it necessary to make a statement in an internal memo. He wrote:

We believe that the design of the rear is not necessarily a North American feature, rather it is a product of the age, as tail wings have regularly been used by Italian body designers since the mid-1950s in connection with aerodynamic studies. If one imagines the car without the proposed tail wings, then in terms of the arrangement of design elements such as lights, bumpers. etc., the rear aspect of the 220 SE of 1959 represents the tail configuration that is the most copied and remodelled by other manufacturers of all time.

The designation ‘S’ continued and expanded into the SE model and, although never described as a ‘Sonderklasse’, the ‘S’ remained synonymous with any ‘flagship’ versions of each model and in this case the 300 SE (W 112) was presented in 1961.

It was fitted as standard with the ‘Adenauer’ M 189 big block 6-cylinder, fuel-injected engine, air suspension and the newly developed automatic transmission. A longer version was introduced in 1963, which again started off a new tradition in Mercedes-Benz luxury class saloons: the ‘lang’ (long) wheelbase offering rear passengers significantly more legroom and comfort. The ‘L’ designation was not used officially until 1965 with the W 109 300 SEL.

The 108 and 109 saloons replaced the ‘Fintail’ in 1965 with an initial line-up of the 250 S, 250 SE and the 300 SE for the W 108 and a single W 109 300 SEL.

The 108s were the generic models fitted with conventional steel springs but the 109 was offered as an air-sprung variant of the model series 109, available from the outset with a 10cm (4in) longer wheelbase. Both models introduced a V8 engine into the range, predominantly to be able to compete with the North American market.

The W 111 300 SE flagship ‘Fintail’.

Mercedes-Benz W 109 300 SEL, 1965–67.

The W 108 SE model clearly shorter than the SEL.

The forerunner to the S-Class bears the features of a competitive racing car. On test runs on the Hockenheimring racing track in preparation for three factory teams’ participation in the 24-hour Spa-Francorchamps race in the summer of 1969.

The 6.3 M 100 engine ‘shoe-horned’ into the W 109.

The production version of the 300 SEL 6.3.

The 108 and the 109s were the last of the ambiguous ‘S’- designated vehicles before the true Sonderklasse W/V116 of 1972, although there was something else that pointed the way to the future S-Class models and that was discreet power. The Americans referred to it as a ‘sleeper’ and the British called it a ‘Q’ car.

It all started with the W 109 300 SEL and a taunt from an auto journalist that Mercedes only build good ‘grandpa cars and taxis’. Eric Waxenberger, head of a special development department, decided to put the German press in their place.

Working at night, in his own time and without the knowledge of his superiors, he took a rejected 300 SEL body from Sindelfingen and the 6.3 M 100 from the 600 and prepared them to race, only informing Rudolf Uhlenhaut what he was doing when it was prepared to enter the Macau Enduro in 1969. It went on to finish first in the six-hour race and then second in the Spa 24-hours.

The same journalists that taunted him earlier now had to eat their words: ‘This automobile is the most the stimulating, desirable four-door saloon to appear since the Model J Duesenberg.’ Road & Track called it simply, ‘The greatest saloon car in the world’.

So successful were they, even though they were nearly three times more expensive than the entry-level 280 SEL, that they succeeded in selling 6,526; ironically using more M 100 engines than the 600.

With the addition of exceptional comfort and luxurious interior fittings, it also rivalled the performance of many sports cars of the day.

What this did for the powers that be at Mercedes Daimler was to cement the ideas that an ‘Uber saloon’ was necessary, and even though the 116 S-Class was already in the ‘pipeline’, it encouraged them that further investment in a stand-alone ‘Sonderklasse’ was the way to go.

UNSAFE AT ANY SPEED

For the many decades that followed the invention of the motor car, vehicle safety was usually based upon nothing more than the empirical knowledge that was gleaned from production and/or motor racing; and even then, it usually meant little more than striving for a car to be as stable and robust as possible and have good handling characteristics.

‘Safety’ became the ‘elephant in the room’ and vehicle manufacturers deigned not to even mention the word for fear of reminding potential customers that the motor car could bring with it death or injury. However, every passing year that brought an increase in vehicle numbers also brought with it a sharp statistical rise in death and serious injuries from vehicle accidents.

Ralph Nader’s book, Unsafe at Any Speed, highlighted the serious inadequacies in vehicle safety. The opening line to his book gave not only the American automobile market (at which it was aimed) a wake-up call, but the rest of the world too:

Ralf Nader, author of Unsafe at any Speed, at the Senate hearing in 1966 triggered by his book.

For over half a century the automobile has brought death, injury and the most inestimable sorrow and deprivation to millions of people.

Having already set up The Aviation Safety and Research Facility at Cornell University, visionaries such as Hugh de Haven understood that the same principles that apply to aircraft safety, also apply to vehicle accidents. Against much political lobbying and opposition he managed to set up a more generic, all-encompassing crash injury and research facility. He once said:

We will get into anybody’s automobile, go any desired distance at dangerous speeds, without safety belts, without shoulder harness, and with a very minimum of padding or other protection to prevent our heads and bodies from smashing against the inside of a car in an accident. The level of safety which we accept for ourselves, our wives and our children is, therefore, on a par with shipping fragile valuable objects loose inside a container… People knew more about protecting eggs in transit than they did about protecting human heads.

The world was at last beginning to understand that more could be done to save life and limb but, more importantly, much of the responsibility was laid firmly at the feet of the ‘vehicle’ manufacturer.

Much was already known about ‘active safety’ or ‘primary safety’ – terms used to refer to mechanical technology such as good handling, good steering and stopping capabilities, which, in themselves, had already greatly assisted in the prevention of many accidents, but this wasn’t enough.

De Haven’s research‘provided strong evidence that the human body was less fragile than had been generally assumed, that the structural environment was the dominant cause of injury – leading to such key safety measures as the three-point seat belts and airbags.

For many years, Hugh de Haven had been viewed as a ‘crackpot scientist’ of little merit; however, a chance meeting between de Haven and a police investigator during a safety talk at the Indianapolis State police headquarters was the beginning of a new understanding of vehicle safety.

Sergeant Elmer Paul was investigator of RTC (Road Traffic Collision) with the Indianapolis State Police Department and he had already recognized what he referred to as the ‘second impact or human collision’ as being the primary cause of death and injury in vehicles. He approached de Haven after the seminar with an offer of assistance and very quickly a new term was being ‘bandied’ about: ‘passive safety’, the recognition of and components needed to protect occupants inside a vehicle. For example:

• Passenger safety cell

• Crumple zones

• Seat belts

• Interior impact resistance

FROM ‘SPECIAL’ TO ‘SAFETY’

Mercedes, on the other hand, had visionaries such as Béla Barényi who, from the very early days of his career, decided that safety was everything, so much so that he even dared to tell Wilhelm Haspel, during his first interview, that they were ‘doing it all wrong’, before going on to tell him why items such as steering and steering wheel could be designed to enhance the safety of the occupants instead of ‘skewering’ them.

From what started as a little wood shed on the edges of the Sindelfingen plant, hand-built carriages that would propel vehicle bodies toward walls; the vehicle safety and development department became a full-blown test centre. By 1957, a test track had been built adjacent to the Untertürkheim plant, which included a skid pad featuring concentrically arranged circular tracks with different surfaces where vehicles could be tested on blue basalt, concrete, slippery asphalt and large cobblestones, with an integrated sprinkler system allowing wet-surface testing.