7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Lord Cockburn, Victorian defender of Edinburgh's beauties, describes Calton Hill as 'the Glory of Edinburgh'. 'It presents us,' enthused Cockburn, 'with the finest prospects both of its vicinity and the city… it is adorned by beautiful buildings dedicated to science and to the memory of distinguished men. 'Following on from the success of Arthur's Seat, the Journeys and Evocations series continues with a look at the events and folklore surrounding Edinburgh's iconic Calton Hill. Standing only 338 ft (103m) high, this small hill offers a fascinating view of Edinburgh both literally and historically. The book brings together prose, poetry and photographic images to explore the Calton Hill's role in radical nationalist politics through the centuries as well as taking a look at the buildings, philosophy and intrigue of a central part of Edinburgh's landscape. Two of the city's leading storytellers, Donald Smith, director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre… and historian and writer Stuart McHardy, have sifted through the centuries to compile the remarkable guide to Edinburgh's famous landmark. EDINBURGH EVENING NEWS on Arthur's Seat.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 141

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

STUART McHARDYis a writer, occasional broadcaster and storyteller. Having been actively involved in many aspects of Scottish culture throughout his adult life – music, poetry, language, history, folklore – he has been resident in Edinburgh for over a quarter of a century. Although he has held some illustrious positions including Director of the Scots Language Resource Centre in Perth and President of the Pictish Arts Society, McHardy is probably proudest of having been a member of the Vigil for a Scottish Parliament. Often to be found in the bookshops, libraries and tea-rooms of Edinburgh, he lives near the city centre with the lovely (and ever-tolerant) Sandra and they have one son, Roderick.

DONALD SMITHis Director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre at Edinburgh’s Netherbow and a founder of the National Theatre of Scotland. For many years he was responsible for the programme of the Netherbow Theatre, producing, directing, adapting and writing professional theatre and community dramas, as well as a stream of literature and storytelling events. He has published both poetry and prose and is a founding member of Edinburgh’s Guid Crack Club. He also arranges story walks around Arthur’s Seat.

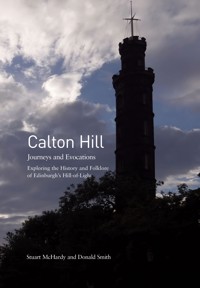

Calton Hill

Journeys and Evocations

Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2013

eBook 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-908373-85-4

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-66-3

The publishers acknowledge the support ofSeeing Stories and Creative Scotlandtowards the publication of this volume.

Map by Jim Lewis

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith 2013

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Calton Hill Map

A Victorian Viewpoint – Robert Louis Stevenson

Part 1 A Radical Tour

Part 2 Pillars of Folly and Wisdom

The Vigil

A Little Magic and Mystery

The Declaration of Calton Hill

Acknowledgements

The authors of this book are grateful to the Scottish Storytelling Forum for its encouragement of this storyguide to Calton Hill, and to the European ‘Seeing Stories’ landscape narrative project, which is supported by the EU Cultural Programme, funded by the European Commission. We also acknowledge the research of ‘Scotland’s Cultural Heritage’, into the City Observatories presented in A Caledonian Acropolis by David Gavine and Laurence Hunter, and the City of Edinburgh Council’s exhibition in the Nelson Monument. For those seeking further information about the streets around Calton Hill we recommend Ann Mitchell’s excellent book The People of Calton Hill. The content of this volume however reflects the views only of the authors, and the information and its use are not the responsibility of the European Commission or any other cited source, but of the authors.

We are delighted that, following the success of our first volume Arthur’s Seat: Journeys and Evocations, Luath Press is developing a Journeys and Evocations series to reach out across Scotland. We look forward to more evocations of our and your special places.

Introduction

Edinburgh’s Calton Hill is a volcanic fragment, stubbornly enduring as an untamed space encircled by the city. It was established in 1725 as one of the world’s earliest public parks, which was then later populated with a striking – if strange – assortment of monuments. ‘Edinburgh,’ suggested 20th century bard Hugh MacDiarmid, in a poem of that name, ‘is a mad god’s dream.’ He was surely standing on Calton Hill as he described Leith and the estuary of the Forth ‘cleaving to sombre heights’.

But MacDiarmid was only the latest in a long line of poets and philosophers to be gobsmacked by Calton Hill. Lord Cockburn, the Victorian defender of Edinburgh’s beauties and inspirer of today’s Cockburn Association, was lavish in his eulogy on this exceptional urban landscape. Writing to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh in 1849,he describes Calton Hill as ‘the Glory of Edinburgh’.

‘It presents us,’ enthused Cockburn, ‘with the finest prospects both of its vicinity and the city… it is adorned by beautiful buildings dedicated to science and to the memory of distinguished men… that sacred mount is destined, I trust, to be still more solemnly adorned by good architecture, worthily applied, so as the walks and the prospects and the facilities of seeing every edifice in proper lights and from proper distances be preserved, and only great names and great events be immortalised; it cannot be crowned by too much high art.’

Today, Edinburgh City Council and the Edinburgh UNESCO World Heritage Trust, which guards Edinburgh’s designation as a World Heritage Site, are both labouring admirably to fulfil Cockburn’s remit, restoring the diverse monuments and fostering a sense of the Hill as a unified and unique landscape. But they are not wholly in control: Calton Hill has its own alternative energies. A focus of ancient rituals, modern performances, and political demonstrations, Calton Hill is a public park which is an ungated inner city space: uncultivated and subject to the licence of the night, as well as the enlightenment of the day.

Many artists have been drawn to Calton Hill, as our Journeys and Evocations will show, but perhaps pride of place should be accorded to Edinburgh’s own Robert Louis Stevenson. Stevenson was a child of the Edinburgh Enlightenment and of its unique concatenation of philosophers, engineers, lawyers and ministers. But what he saw from Calton Hill was a more mixed inheritance of light and dark, mental aspiration mingled with social squalor, moral ideals with human reality. Calton Hill is ‘the eye’ of Edinburgh through which everything can be seen in nature and in human culture. Even in the Hill’s immediate vicinity, the classical order of Waterloo Bridge looks down on the shady chasms of Calton Road below.

Stevenson’s famous description of the view from Calton Hill, published in 1889, is our first evocation but towards the end of his life the author, exiled by ill-health to Samoa, returned to Calton Hill in a little noticed story:The Misadventures of John Nicholson. The hero is a young man divided like the youthful Stevenson between the respectable Edinburgh world of prosperous terraces (Randolph Crescent in this case) and the dubious twilight of jails and slums that still wrapped itself around the south side of Calton Hill. Clearly, Stevenson is recalling over the decades his own borderland experiences on Edinburgh’s Hill of Light.

He proceeded slowly back along the terrace in a tender glow; and when he came to Greenside Church, he halted in a doubtful mind. Over the crown of the Calton Hill, to his left, lay the way to Collette’s, where Alan would soon be looking for his arrival, and where he would now no more have consented to go than he would have wilfully wallowed in a bog…But right before him was the way home, which pointed only to bed, a place of little ease for one whose fancy was strung to the lyrical pitch, and whose not very ardent heart was just then tumultuously moved.The hill-top, the cool air of the night, the company of the great monuments, the sight of the city under his feet, with its hills and valleys and crossing files of lamps, drew him by all he had of the poetic, and he turned that way; and by that quite innocent reflection, ripened the crop of his venial errors for the sickle of destiny.

On a seat on the hill above Greenside he sat for perhaps half an hour, looking down upon the lamps of Edinburgh, and up at the lamps of heaven. Wonderful were the resolves he formed; beautiful and kindly were the vistas of future life that sped before him… At that juncture the sound of a certain creasing in his greatcoat caught his ear. He put his hand into his pocket, pulled for the envelope that held the money,and sat stupefied… He looked up. There was a man in a very bad hat a little to one side of him, apparently looking at the scenery; from a little on the other side a second nightwalker was drawing very quietly near.Up jumped John. The envelope fell from his hands; he stooped to get it, and at the same moment both men ran in and closed with him.

A little after, he got to his feet very sore and shaken, the poorer by a purse that contained exactly one penny postage-stamp, by a cambric handkerchief, and by the all-important envelope. Here was a young man on whom, at the highest point of loverly exaltation, there had fallen a blow too sharp to be supported alone; and not many hundred yards away his greatest friend was sitting at supper – ay and even expecting him…

Close under Calton Hill there runs a certain narrow avenue, part street, part by-road. The head of it faces the doors of the prison; its tail descends into the sunless slums of the Low Calton. On one hand it is overhung by the crags of the hill, on the other by an old graveyard. Between these two the roadway runs in a trench, sparsely lighted at night, sparsely frequented by day, and bordered, when it has cleared the place of tombs, by dingy and ambiguous houses. One of these was the house of Colette; and at this door our ill-starred John was presently beating for admittance.

So, in Stevenson’s recall, Calton Hill and its surroundings embody all the Jekyll and Hyde qualities of Edinburgh. It looks upwards to the starlit heavens while retaining something of Erebean night. Welcome to these journeys into this much-evoked yet little understood glory – ‘a mad god’s dream’.

A Victorian Viewpoint

Robert Louis Stevenson

The east of new Edinburgh is guarded by a craggy hill, of no great elevation, which the town embraces. The old London Road runs on one side of it; while the New Approach, leaving it on the other hand, completes the circuit. You mount by stairs in a cutting of the rock, to find yourself in a field of monuments. Dugald Stewart has the honour of situation and architecture; Robert Burns is memorialised lower down upon a spur; Lord Nelson, as befits a sailor, gives his name to the topgallant of Calton Hill. This latter erection has been differently and, yet, in both cases, aptly compared to a telescope and a butter-churn; comparisons apart, it ranks among the vilest of men’s handiworks. But the chief feature is an unfinished range of columns, ‘the Modern Ruin’ as it has been called – an imposing object from far and near, and giving Edinburgh, even from the sea, that false air of a Modern Athens which has earned for her so many slighting speeches. It was meant to be a National Monument and its present state is a very suitable monument to certain national characteristics. The old Observatory—a quaint brown building on the edge of the steep—and the new Observatory—a classical edifice with a dome—occupy the central portion of the summit. All these are scattered on a green turf, browsed over by some sheep.

The scene suggests reflections on fame and on man’s injustice to the dead. You see Dugald Stewart rather more handsomely commemorated than Burns. Immediately below, in the Canongate Churchyard, lies Robert Fergusson, Burns’ master in his art, who died insane while yet a stripling and, if Dugald Stewart has been somewhat too boisterously acclaimed as the Edinburgh poet, he is most unrighteously forgotten. The votaries of Burns, a crew too common in all ranks in Scotland and more remarkable for number than discretion, eagerly suppress all mention of the lad who handed to him the poetic impulse and, up to the time when he grew famous, continued to influence him in his manner and the choice of subjects. Burns himself not only acknowledged his debt in a fragment of autobiography, but erected a tomb over the grave in Canongate Churchyard. This was worthy of an artist, but it was done in vain; and although I think I have read nearly all the biographies of Burns, I cannot remember one in which the modesty of nature was not violated, or where Fergusson was not sacrificed to the credit of his follower’s originality. There is a kind of gaping admiration that would fain roll Shakespeare and Francis Bacon into one, to have a bigger thing to gape at; and a class of men who cannot edit one author without disparaging all others. They are indeed mistaken if they think to please the great originals – and whoever puts Fergusson right with fame – cannot do better than dedicate his labours to the memory of Burns, who will be the best delighted of the dead.

Of all places for a view, this Calton Hill is perhaps the best, as you can see the Castle, which you lose from the Castle, and Arthur’s Seat, which you cannot see from Arthur’s Seat. It is the place to stroll on one of those days of sunshine and east wind which are so common in our more than temperate summer. The breeze comes off the sea, with a little of the freshness, and that touch of chill, peculiar to the quarter, which is delightful to certain very ruddy organisations and greatly the reverse to the majority of mankind. It brings with it a faint, floating haze, a cunning decolouriser, although not thick enough to obscure outlines near at hand. But the haze lies more thickly to windward at the far end of Musselburgh Bay and over the Links of Aberlady and Berwick Law and the hump of the Bass Rock it assumes the aspect of a bank of thin sea fog.

Immediately underneath, upon the south, you command the yards of the High School, and the towers and courts of the new Jail—a large place, castellated to the extent of folly, standing by itself on the edge of a steep cliff, and often joyfully hailed by tourists as the Castle. In the one, you may perhaps see female prisoners taking exercise like a string of nuns; in the other, schoolboys running at play and their shadows keeping step with them. From the bottom of the valley, a gigantic chimney rises almost to the level of the eye – a taller and a shapelier edifice than Nelson’s Monument. Look a little further, and there is Holyrood Palace, with its Gothic frontal and ruined abbey, and the red sentry pacing smartly to and fro before the door like a mechanical figure in a panorama. By way of an outpost, you can single out the little peak-roofed lodge, over which Rizzio’s murderers made their escape and where Queen Mary herself, according to gossip, bathed in white wine to entertain her loveliness. Behind and overhead, lie the Queen’s Park, from Muschat’s Cairn to Dumbiedykes, St Margaret’s Loch, and the long wall of Salisbury Crags; and thence, by knoll and rocky bulwark and precipitous slope, the eye rises to the top of Arthur’s Seat, a hill for magnitude, a mountain in virtue of its bold design, upon your left. Upon the right, the roofs and spires of the Old Town climb one above another to where the citadel prints its broad bulk and jagged crown of bastions on the western sky. Perhaps it is now one in the afternoon and at the same instant of time, a ball rises to the summit of Nelson’s flagstaff close at hand, and, far away, a puff of smoke followed by a report bursts from the half-moon battery at the Castle. This is the time-gun by which people set their watches, as far as the sea coast or in hill farms upon the Pentlands. To complete the view, the eye enfilades Princes Street, black with traffic, and has a broad look over the valley between the Old and the New Town: here, full of railway trains and stepped over by the high North Bridge upon its many columns, and there, green with trees and gardens.

On the north, the Calton Hill is neither so abrupt in itself nor has it so exceptional an outlook, and yet even here it commands a striking prospect. A gully separates it from the New Town. This is Green side, where witches were burned and tournaments held in former days. Down that almost precipitous bank, Bothwell launched his horse, and so first, as they say, attracted the bright eyes of Mary. It is now tessellated with sheets and blankets out to dry, and the sound of people beating carpets is rarely absent. Beyond all this, the suburbs run out to Leith; Leith camps on the seaside with her forest of masts; Leith roads are full of ships at anchor; the sun picks out the white pharos upon Inchkeith Island; the Firth extends on either hand from the Ferry to the May; the towns of Fifeshire sit, each in its bank of blowing smoke, along the opposite coast; and the hills enclose the view, except to the farthest east, where the haze of horizon rests upon the open sea. There lies the road to Norway: a dear road for Sir Patrick Spens and his Scots Lords; and yonder smoke on the hither side of Largo Law is Aberdour, from whence they sailed to seek a queen for Scotland.