Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

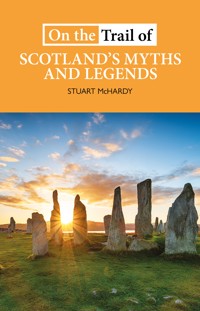

A journey through Scotland's past from the earliest times through the medium of the awe-inspiring stories that were at the heart of our ancestors' traditions and beliefs. As the art of storytelling bursts into new flower, many tales are being told again as they once were. As On the Trail of Scotland's Myths and Legends unfolds, mythical animals, supernatural beings, heroes, giants and goddesses come alive and walk Scotland's rich landscape as they did in the time of the Scots, Gaelic and Norse speakers of the past. Visiting over 170 sites across Scotland, Stuart McHardy traces the lore of our ancestors, connecting ancient beliefs with traditions still alive today. Presenting a new picture of who the Scots are and where they have come from, this book provides an insight into a unique tradition of myth, legend and folklore that has marked the language and landscape of Scotland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 276

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

STUART MCHARDY has lectured and written on many aspects of Scottish history and folklore both in Scotland and abroad. His life-long interest in all aspects of Scottish culture led to his becoming a founding member and president of the Pictish Arts Society. From 1993-98 he was also the Director of the Scots Language Resource Centre in Perth. Following many years on the seminal McGregor’s Gathering (BBC Radio Scotland) he has continued to broadcast on radio and television. He lectures annually at Edinburgh University’s Centre for Continuing Education in the areas of Scottish mythology, folklore and legend. He is also the author of a children’s book, The Wild Haggis and the Greetin-faced Nyaff (Scottish Children’s Press, 1995) and has had poetry in Scots and English published in many magazines. Born in Dundee, McHardy is a graduate of Edinburgh University and lives in that city today with his wife Sandra.

Books in the Luath On the Trail of series

On the Trail of Bonnie Prince Charlie

On the Trail of the Holy Grail

On the Trail of John Muir

On the Trail of John Wesley

On the Trail of King Arthur

On the Trail of Mary Queen of Scots

On the Trail of the Pilgrim Fathers

On the Trail of Queen Victoria in the Highlands

On the Trail of Scotland’s History

On the Trail of Robert Burns

On the Trail of Robert Service

On the Trail of Robert the Bruce

On the Trail of Scotland’s Myths and Legends

On the Trail of William Shakespeare

On the Trail of William Wallace

First Published as Scotland: Myths, Legend and Folklore 1999

Revised Edition 2005

Reprinted 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018

This Edition 2024

ISBN: 978-1-913025-15-1

Maps by Jim Lewis

Illustrations by Nulsh the Bold, Scottish Cartoon Art Studio, Glasgow

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by

3btype.com

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Stuart McHardy

In Memoriam

Martin Hendry

1943–1999

Contents

Index Map

Map A

Map B

Map C

Map D

Preface

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 The Hollow Hills

The Eildon Hills

Tomnahurich

Calton Hill

The Fairy Hill of Aberfoyle

The Two Hunchbacks

CHAPTER 2 The Goddess in the Landscape

The Cailleach

The Carlin

Bride / St Brigit

CHAPTER 3 The Cateran

Serjeant Mor

Cam Ruadh

Ledenhendrie

CHAPTER 4 The Turn of the Seasons

Beltane

Samhain

CHAPTER 5 Saints

St Serf

St Kentigern

St Maelruba

St Merchard

St Columba

St Abban

CHAPTER 6 Supernatural Beings

Nessie

Kelpies

Loch Slochd

Loch Pityoulish

Loch nan Dubrachan

A Female Kelpie

Silkies

Urisks

Brownies

Glaistigs and Gruagachs

A Lochaber Glaistig

An Argyll Glaistig

CHAPTER 7 Witches and Warlocks

A Spell on Eilean Maree

Kate McNiven

North Berwick Witches

The Witches of Auldearn

The Witch of Laggan

Michael Scot

The Wizard Laird of Skene

An Edinburgh Warlock

CHAPTER 8 Picts

The Maiden Stone

Martin’s Stane

A Pictish Centre?

Sueno’s Stone

Vanora’s Stone

Norrie’s Law

The Sleeping Pict

CHAPTER 9 Giant Lore

Lang Johnnie Moir

The Fianna

The Muileartach

The Making of the Outer Hebrides

Guru

Fear Liath Mor

CHAPTER 10 Stone Circles and Standing Stones

Clach Ossian

The Stone of Odin

Deil’s Stanes

Granish Moor

Lang Man’s Grave

Calanish

CHAPTER 11 Wells, Trees and Sacred Groves

Nine Maidens Wells

Bride’s Wells

Clootie Wells

Eye Wells

Moving Wells

The Queen and the Well

Katherine’s Well

The Well in Willie’s Muir

Sacred Trees

The Rowan

The Yew

Sacred Groves

CHAPTER 12 And Then . . .

Calanish

The Cailleach

Cailleach and the landscape

The Cailleach and lochs

Wells

The Cailleach’s House

The Loathly Hag

The Corryvreckan Whirlpool

The Cailleach and deer

Bride

Bride Locations

Breast-shaped mountains

Harvest rites

Bride and the Cailleach

Masculine figures

Conclusion

Further Reading

Key to Map A

Ref

A1 Butt of Lewis: said to be formed from giant’s head

A2 Breasclete: village by Calanais

A3 Loch Roag: loch from which magical cow appeared

A4 Calanish: major standing stone alignment

A5 Lewis: island where Calanais is situated

A6 Taransay: island formed from giant’s head

A7 Harris: said to be part nine-headed giant’s body

A8 Pabbay: island formed from giant’s head

A9 Killegray: island formed from giant’s head

A10 North Uist: said to be part of giant’s body

A11 Benbecula: said to be part of giant’s body

A12 South Uist: said to be part of giant’s body

A13 Eriskay: island formed from giant’s head

A14 Barra: part of giant’s body

A15 Mingualay: island formed from giant’s head

A16 Sound of Bernera: island formed from giant’s head

A17 Iona: important sacred centre

A18 Cuidrach: site of battle in Skye

A19 Bracadale: site of story of female kelpie

A20 Sound of Mull: site of hag’s death

A21 Mull – Carn na Caillich: cairn named after hag

A22 Glen Duror: site of glaistig story

A23 Glencoe: site of Pap of Glencoe

A24 Fort William: mentioned in tale of Serjeant Mor

A25 Raasay: mentioned in tale of nine-headed giant

A26 Eigg: site of holy well

A27 Rum: mentioned as raided by nine-headed giant

A28 Loch nan Dubrachan: location of tale of Kelpie

A29 Dun Dreggan: hillfort where Finn killed a dragon

A30 Glenmoriston: site of story of St Merchard

A31 Applecross: ancient ecclesiastical site

A32 Loch Maree: site of pagan rites

Key to Map B

Ref

B1 Maes Howe: magnificent chambered tomb in Orkney

B2 Stenness: major stone circle in Orkney

B3 Orkney: site of major megalithic remains

B4 John o Groats: location of Silkie story

B5 Forsinard: site of giant story

B6 Maiden Pap: breast-shaped hill

B7 Navidale: site of ancient sacred enclosure

B8 Shetland: location of fire festival

B9 Edderton: story of giant putting stones

B10 Ben Wyvis: story of the Cailleach

B11 Strathpeffer: story of giants putting stones

B12 Dingwall: site of pagan practices

B13 Clootie Well: ancient healing well

B14 Culloden: site of another clootie well

B15 Inverness: location of Tomnahurich

B16 Tomnahurich: ancient sacred mound and cemetery

B17 Auldearn: site of witch activities

B18 Loch Loy: site of witch activities

B19 Forres: site of witch coven

B20 Knock Of Alves: site of witch coven

B21 Burghead: site of midsummer fire festival

B22 Banff: site of ancient fair

B23 Pitsligo: site of nine maidens well

B24 Strath Dearn: story of well moving to Canada

B25 Loch Slochd: site of kelpie story

B26 Granish Moor: location of prophesying witches

B27 Loch nan Carraigean: site of stone circle

B28 Loch Pityoulish: site of kelpie story

B29 Tullochgorm: location of brownie tale

B30 Loch Uaine: part of thieves’ road

B31 Loch Morlich: part of thieves’ road

B32 Loch an Eilean: part of thieves’ road

B33 Lairig Ghru: pass through Cairngorms linked to Grey Man

B34 Ben Macdui: location of Grey Man of Ben Macdui

B35 Kingussie: mentioned in story of witch of Laggan

B36 Newtonmore: story of wizard eating serpent

B37 Laggan: location of witch of Laggan

B38 Dalarossie: sanctuary site witch failed to reach

B39 Gaick: home of hunter who fought witch of Laggan

B40 Tap o Noth: home of giant

B41 Glen Clunie: possible birthplace of Cam Ruadh

B42 Lochnagar: site of breast-shaped peak

B43 Maiden Stone: Pictish symbol stone with legend

B44 Bennachie: breast-shaped peaks and site of several tales

B45 Balmoral: site of Shandy Dann ceremony at Halloween

B46 Stonehaven: location of midwinter fire festival

B47 Durris: location of midsummer fire festival

B48 Skene: home of Wizard Laird of Skene

B49 Tough: site of nine maidens well

B50 Kildrummy: site of nine maidens well

Key to Map C

Ref

C1 Wigton: location of Bride’s well

C2 Loch Carlingwark: site of ancient votive offerings

C3 Sanquhar: location of Bride’s well

C4 Dundonald: site of St Monenna dedication

C5 Rutherglen: location of Halloween baking ceremony

C6 Carntyne: probable site of fire festival

C7 Glasgow Cathedral: founded by St Kentigern

C8 Tintock: ancient fire site

C9 Dumbarton: site of St Monenna dedication

C10 Roseneath: site of ancient sacred grove

C11 Aberfoyle: site of fairy hill and disappeared minister

C12 Callander: story of Beltane rites

C13 Ben Venue: meeting place of forest spirits

C14 Ben Arthur: Arthurian placename

C15 Balquhidder: location of Beltane rites

C16 Killin: location of Beltane rites

C17 Corryvreckan: great whirlpool linking goddess and Columba

C18 Jura: island south of Corryvreckan

C19 Paps of Jura: breast-shaped peaks

C20 Colonsay: site of story of moving well

C21 Finlaggan: site of story of moving well

C22 Port Ellen: story of princess and frog

C23 Kilchrennan: location of ‘two hunchbacks’ story

C24 Ben Cruachan: mountain associated with Cailleach

C25 Rannoch Moor: hideout of post-Culloden Cateran

C26 Rannoch Moor: The Cailleach’s House

Key to Map D

Ref

D1 Drummochter: associated with wizard Michael Scot

D2 Craigmaskeldie: mountain with Bride association

D3 Glen Esk: Angus glen with Bride association

D4 Cairnwell: site of battle

D5 Glenshee: location of Cateran story

D6 Water of Saughs: site of battle with Cateran

D7 Glen Lethnot: location of Cateran escape route

D8 Cortachy: site of nine maidens well

D9 Memus: location of kelpie stone

D10 Finavon: site of nine maidens dedication

D11 Arthur’s Seat, Strathmore: Arthurian place name

D12 St. Vigean’s: museum of Pictish symbol stones

D13 Glamis: site of nine maidens well

D14 Meigle: Arthurian legend site and museum of Pictish stones

D15 Martin’s Stane: Pictish symbol stone with legend

D16 Pittempton: story of nine maidens and dragon

D17 Bride’s Ring: ancient site

D18 Dundee Law: probable ancient fire site

D19 Invergowrie: site of story of Goors of Gowrie

D20 Barry Hill: legendary prison of Vanora (Guinevere)

D21 Dunsinane: ancient hillfort overlooking Strathmore

D22 Lang Man’s Grave: fallen standing stone with legend

D23 Kinnoull: site of Beltane dragon ceremony

D24 Perth: mentioned in nine maidens section

D25 Murrayshall: location of nine maidens well

D26 Tullybelton: probable ancient fire site

D27 Dunkeld: site of Halloween fires

D28 Aberfeldy: site of Halloween fires

D29 Fortingall: location of ancient yew

D30 Amulree: dedication to St Maelruba

D31 Sma Glen: location of Clach Ossian

D32 Fendoch: legendary site of Fenian fort

D33 Dunmore: reburial site of Ossian

D34 Fowlis Wester: probable fire site, Pictish cross and standing stones

D35 Crieff: location of witch burning tale

D36 Sherrifmuir: site of battle

D37 Stirling Castle: probable nine maidens site

D38 Culross: location of St Serf’s monastery

D39 Loch Leven: St Serf’s Isle

D40 Carlin Maggie/Bishop’s Hill: natural formation associated with hag

D41 Maiden Bore: site of fertility rites

D42 Craig Rossie: Roman site overlooking Strathearn

D43 Tarnavie: location of earth spirit story

D44 Dunning: site of St Serf killing dragon

D45 Newburgh: nine maidens location

D46 Norman’s Law: story of giant putting stones

D47 Cupar: where Pictish silver was sold

D48 St. Andrews: tale of giant putting stone

D49 Norrie’s Law: site of Pictish silver hoard

D50 Balmain: farm where hoard found

D51 Largo Law: story of ghost and buried treasure

D52 Isle of May: ancient holy island

D53 Dysart: St Serf location

D54 North Berwick Law: site of famous witch coven

D55 Traprain Law: ancient tribal capital and possible nine maidens site

D56 Haddington: county town of East Lothian

D57 Calton Hill: ancient fire and fertility site

D58 Holyrood: site of St Triduana’s well

D59 Edinburgh Castle: probable nine maidens site

D60 Earlston: Thomas Learmont spirited away

D61 Eildon Hills: location of Thomas the Rhymer legend

D62 Bodesbeck: story of Brownie of Bodesbeck

D63 Maiden Paps: breast-shaped peaks

D64 Tinto: ancient fire site

Preface

AS A CHILD TOURING SCOTLAND I constantly nagged my parents to visit stone circles, brochs and standing stones. As I grew older I began to realise that many of these ancient sites had stories told of them and I found these stories as entrancing as the sites themselves. Tales were originally handed down through the generations by word of mouth, in Gaelic, Norse or Scots. They survived because they had meaning for both the people telling them and the people listening to them. Before writing this was how all human knowledge was transmitted; tales and legends were of central importance to human society. If they had no significance they would not have survived long enough to have been written down. For many years I have been researching Scottish legend and folklore and though there is much in common with the lore of other countries like England, Ireland, Scandinavia and Wales, our culture is uniquely our own.

I have spent much of my life researching Scotland’s past to try and gain a clearer understanding of who I am. What I have found is that Scotland is not a Celtic country, but a Scottish country in which traditions and beliefs often called ‘Celtic’ are just as rooted in the traditions of Germanic-speaking peoples, like the Scandinavians, the English, and of course Scots speakers. The old phrase ‘We’re aw Jock Tamson’s bairns’ perhaps deserves a postscript: we’re aw mongrels as weel. The traditions and tales in this book are intended to illustrate the diversity and complexity of Scottish culture.

Scotland’s landscape is renowned for its beauty and visitors flock here from all over the world despite our often atrocious weather. I hope these stories show that our landscape is not just rich in beauty but also rich in lore and legend created over thousands of years. As we enter a new and potentially exciting political situation it is important that we try and get as clear a picture as we can of who we are and where we come from.

Stuart McHardy

Introduction

People come from all over the world to visit Scotland. Its beauty is well known – the magnificent mountains, the lonely glens and lush straths, tumbling rivers and placid lochs – all can touch the heart and stir the soul.

For all the vastness of the Scottish landscape, each of its mountains has a particular story connected to it. From the dawn of time, the myths and legends of Scotland and the exploits of those who lived here have come down to us in stories in Gaelic and Scots, tales from times when those languages themselves had yet to breathe.

Writing came to Europe only a few thousand years ago and much of the material in this book comes from before then. People then loved their land even more than we do today: they saw themselves as tied to it in ways modern city-dwellers have long forgotten. Much of the material in this book comes directly from those ancient times, reworkings of the great themes of life and death, love and liberty, told against the background of the Scottish landscape. It was and is a landscape of the eye, the heart and the soul of the peoples who have lived here. Magical animals, supernatural beings, heroes, giants and goddesses walk this landscape. As the ancient art of storytelling bursts into new flower, many of these tales are being told again as they once were.

Many things have changed over the past centuries – languages, religions, technology – but the love of the land survives, the glory in its splendour which informs the substance of its legends. What they tell us above all is that we are not so different from our far-off ancestors, and perhaps in the face of environmental destruction and world-wide pollution we may yet learn from them how to live in better harmony with the earth.

The past few decades have seen a world-wide resurgence of people wanting to know more about their ‘roots’, especially in Europe. Although there are varying reactions all over the world to this situation, here in Scotland we have our own way of doing things. There is a growing interest and participation in the rituals surrounding such ancient sites as the Clootie Well (B13) on the Black Isle, north of Inverness. This ancient sacred well is now a well-known tourist spot and people come from great distances to tie a rag to the trees adjoining the well and to make their wish. This is simply the continuation of an old tradition, once extremely widespread. In this book we shall look at some of the sites and rituals associated with this kind of ancient well-worship.

But there are examples of rituals practised even in Scotland’s cities today. Calton Hill (D57) in Edinburgh – itself a name redolent of ancient belief – is the traditional site for a Beltane fire ceremony which has just been revived. It is now attended by thousands as dusk falls on the 31 April (following the traditional way of counting the new day from when the old one dies). This fire festival once took place all over Britain, a rite of sanctity and fertility. Though the actual ceremony today owes more to Mediterranean influences than traditional Scottish behaviour, the celebration and the use of fire, ritual dance and music all echo the May Day rites that seem to have come from the dawn of time. Other parts of Scotland too have seen their own Beltane fires lit, and other fire festivals such as the Burnin o the Clavie at Burghead (B21) or the Up-Hellya Festival in Shetland are immensely popular.

People are drawn to other ancient sites such as stone circles and these have been the focus of many different types of activity. Some people see happenings, like the reborn druids with their midsummer ceremonies at Stonehenge, as central in new forms of pagan worship. Yet others think they may attract UFOS, since suggestions have been made that they are some kind of portal between worlds. The fascination of such sites seems to be growing stronger. The continuing attraction of Arthurian material has been matched over the past few years by a distinctly mystical interest in the thoughts and beliefs of our Celtic ancestors. More books than ever are published on Celtic and even Pictish subjects but we must remember not to lose our critical faculties. The term Celtic, which should apply only to linguistic matters, now surfaces in all sorts of areas and I suppose it is only a matter of time before Arbroath smokies and Forfar bridies are presented as Celtic food!

It has been overlooked by many scholars who have written on ‘Celtic’ society that the last Celtic-speaking tribal warrior society did not disappear until the eighteenth century in Scotland. When the Highland, Lowland and English followers of Prince Charles Edward Stewart were slaughtered at Culloden on 16 April 1746 it truly was the end o an auld sang. The tribal society of the Gaelicspeaking areas of Scotland was already in terminal decline but it is still a remarkable fact that so little has been written about that society. It is as if the body politic of the British State was put into shock by the Jacobite Rebellion and that Scottish history has been suffering ever since. The classic texts on the Celts concentrate on Irish and Welsh material despite the fact that Celtic society continued for hundreds of years later – here in Scotland. And it was a life in which learning was passed on through story and song.

The history of Scotland has long been obscured because of a few historical events. Little written material survives from ancient times due to various raids and invasions. The earliest of these started in the ninth century with the Vikings, who often raided monasteries – the natural home for written material as well as the precious metals they were seeking. Later came the invasion of the English king Edward Longshanks in the thirteenth century. Edward destroyed all documents he could find as they were sure to undermine his opportunistic and dishonest claims to be sovereign lord of Scotland. What he did not destroy was taken south to England and disappeared.

Later, the Reformation saw the unleashing of fanatical mobs who burned books and destroyed great art, claiming it was all ‘Papist’. Because of this and because of the close links between Ireland and Scotland, Scottish culture has come to be presented as an Irish import through Gaelic, or an English import through the medium of Anglo-Saxon, which influenced Scots north of the border.

The heroes that populate our landscape come from various traditions – from the Gaelic Finn MacCool and his Fenian warriors to stories of Arthur and his cheating queen, which have survived from times when people in the Southwest, the East and North spoke an ancestor of modern-day Welsh. There are also tales of giants and giantesses which step straight out of the traditions of Scandinavia, first told in a language related to the Scots and English we hear today.

Scotland has a complex history indeed and most of it was initially passed on through the spoken word. It is the spoken word attached to the landscape that has provided the material for this book. I have found these stories in earlier published material mainly – often guidebooks and local histories whose authors had no particular interest in legendary material, seeing it only as adding a bit of colour. The nineteenth century in particular saw many such publications, triggered by the start of tourism, given such powerful impetus by the works of Sir Walter Scott. Today as we begin to realise we have had little access to Scotland’s actual history, such material takes on new significance.

Recent research in Australia has shown the capability of oral tradition to pass on factual material over thousands of years. Aboriginal tales of giant marsupials, for example, had been dismissed as the fantasy of primitive savages. Excavation of the bones of such creatures, now called diprodotons, and sometimes found in sites over 20,000 years old, tells a different story. Other tales mention vocanic eruptions that have also since been confirmed by excavation. The fact is that while mainstream European scholarship has long asserted that oral tradition was made redundant when writing was introduced, the spoken word has never ceased to be important.

Much of the material in this book has a long pedigree. How long may be impossible to say, but the intriguing possibility is that the story of the raising of the great stone circle of Calanish on Lewis, passed by word of mouth from generation to generation, is true.

Some stories, like those of Finn MacCool or Arthur, exist in many places because they were told in those places and it is part of the traditional art of storytelling to place stories in a landscape the audience knows. Without such location the stories would lose much of their relevance. Such stories include ones of an ancient Mother Goddess known as the Cailleach in Gaelic and the Carlin in Scots, stories associated with our magnificent and decidedly moody mountains, tales of lochs and rivers inhabited by supernatural creatures, stories of romance and heroism associated with the Pictish symbol stones, tales of revenge, and harrowing tales of the persecution of women as witches perhaps because they held on too strongly to the old ways.

We should remember that Scotland has gone through many significant changes since people started arriving here almost 10,000 years ago. Some of these changes we know about, many we never will. What is significant is that the legendary landscape has retained many ancient ideas despite these often substantial changes. The old idea that major change was a result of invasions by increasingly superior and technologically advanced warrior aristocrats is a fantasy of the ruling classes. We now know that the development of new styles of pottery represent technological advance in itself rather than invasion. Language change was also presented as a result of military conquest. The reality is that Scotland has spoken different languages at different times. It has been predominantly P-Celtic-speaking (the ancestor of modern day Welsh) as well as Q-Celtic-speaking (the ancestor of modern day Gaelic) and Germanic-speaking, as today, when most of us have Scots or Scottish-English as our first language. However at different times from the eighth to the eleventh centuries there were Germanicspeaking Norse settlements in different parts of the country and there are suggestions today that Germanic speakers settled here during or after the short visitations of the Romans. There are also suggestions that perhaps Germanic tribes were settling our southeastern coasts almost as early as the Gaels are said to have founded Dalriada, around 500 AD.

Legendary material, however, has a way of passing by such upheavals – as if the psycho-sociological relevance of the stories runs deeper than language itself within society. This might explain why we have the Cailleach in Gaelic matched so precisely by the Carlin in Scots.

Maybe the old ways are not yet totally gone. Apart from resurgences of well-dressing and the Beltane fires, and the survivals of other rituals like the various midwinter fire festivals, these tales can perhaps help us see more clearly how our ancestors lived and what they believed. Industrialisation and literacy are, like the habit of living in cities, very recent in terms of the history of this land, and our much-loved landscape retains a great deal from earlier times.

I have divided the book into topics which link tales of similar kinds and hope this will lead the reader into a deeper understanding of our landscape and hopefully also into physical exploration of this beautiful, ever-changing and lore-laden land.

CHAPTER 1

The Hollow Hills

IN VARIOUS PARTS OF THE country different heroes are believed to be resting below ground awaiting the call to come forth to the aid of Scotland. It may be that such stories are connected to the ancient beliefs associated with the great chambered cairn burials known throughout our landscape. Scholars nowadays see these as communal burials and no longer as the tombs of kings or other supposed high-status leaders of contemporary society. These chambered tombs often contained the bones of several individuals, though not all of the bones. Skulls and thigh bones seemed to dominate, suggesting a link with the well-known motif on Scottish gravestones, the skull-and-crossbones, portrayed in countless Hollywood films as the flag of pirates. It is now thought that these were the sites of specific rites on the great feast days of the year. Samhain, today conflated with Halloween, was very much a feast of the dead in tribal times. The bones were brought forth at these times and used in rituals in which the spirits of the dead would be asked to ensure that the seeds planted in the earth would grow in the coming spring. This also might help to explain the importance of genealogies or family histories in Scotland, for if you are asking your ancestors for direct help it seems a good idea to be sure of who you are talking to! Such genealogies, passed on by word of mouth, went back for many generations and the seannachie, the traditional genealogist of the Highland clans, had his counterpart at the coronation of kings, as well as at the investiture of clan chiefs.

The Eildon Hills

The Eildon Hills (D61) to the south of Melrose in the Borders were known long ago to the invading Romans as Trimontium, the three-peaked hills. It has long been told locally that King Arthur himself is sleeping inside the Eildons awaiting his call to arms.

A local horse-dealer called Canonbie Dick, a fearless character ‘wha wid hae sellt a cuddy tae the Deil himsel’, was riding home one evening by the Eildons when he was hailed by a man in very old-fashioned dress. He asked to buy the horses Dick had with him and, after some hard bargaining, paid for them in ancient gold coins before disappearing into the night. This happened several times and at last Dick’s curiosity got the better of him and he suggested the mysterious stranger take him home for a drink to seal the bargain. Reluctantly, the stranger agreed but warned Dick that he would be going into danger, particularly if he lost his nerve. This only served to intrigue the horse-dealer even more and he urged the stranger to hurry. The stranger led Dick to a hummock on the side of the Eildons still known today as the Lucken Hare, where to Dick’s surprise he opened a concealed door in the side of the hill. At once he found himself inside a huge torch-lit cavern full of rows of stalls, and in each stall a sleeping horse waited with a warrior clad in armour. The horses were all black as coal, as was the armour of the sleeping warriors. On a great table lay a massive sword and a horn of like size. The stranger told Dick that he was Thomas of Ercildoun, the famous Thomas the Rhymer, and he uttered the fateful words, ‘He that shall sound that horn and draw that sword shall, if his heart fail him not, be king over all broad Britain. But all depends on courage, and much on your taking the sword or horn first.’

Dick took up the horn and with a trembling hand managed to blow a feeble note. In response a thundering sound erupted and the men and horses began to rise. Horses stamped their hooves and snorted as warriors sprang to their feet, sword in hand. Dick was terrified and dropped the horn, reaching his hand to lift the enchanted sword. A great voice rang out:

Woe to the coward that ever he was born

Who did not draw the sword before he blew the horn.

At that a mighty wind came up and Dick was tossed in the air and thrown clean out of the cave. He had made the wrong choice. The following morning he was found lying on the hillside by local shepherds. Lifting his head he told his strange story, fell back and died.

A variant on this story is that once the Rhymer has bought enough coal-black horses the warriors will sally forth from their slumbers to put the world to rights. In other legends the sleeping warriors are King Arthur and his knights awaiting the call to come to the aid of Britain.

It is said that the Eildons are where Thomas Learmont of Ercildoun, now called Earlston (D60), was spirited away by the Queen of the Fairies for seven years. When at last he returned he had the gift of prophecy. Thomas of Ercildoun is believed to have been a real figure who lived in the thirteenth century and many folk rhymes and prophecies are attributed to him. The spot where he was spirited away is marked by a stone where there once was an ancient tree – probably a yew – now known as the Eildon Tree Stone. Such is Thomas the Rhymer’s hold on imagination that he is mentioned in several of Scotland’s earliest histories and is said to have lived in many parts of the country.

Thomas

There are many versions of his story but all agree he was on Eildon when he saw a fair lady dressed all in green, her horse’s mane dressed with silver bells, riding towards him. Taken by both her beauty and her majesty, he doffs his hat and kneels before her. She knows who Thomas is and says that she has come to see him. She takes him up behind her on her horse and she heads for Elfinland. When they come to a red river, Thomas asks what river this can be.

‘This,’ she tells him, ‘is the river of blood that is shed on the earth in one day.’

They ride on and come to a crystal river. Again Thomas asks what river this can be and the Elfin Queen tells him, ‘This is the river of tears that is spilled on the earth in one day.’

On and on they ride until they come to a thorny road and Thomas asks what road this can be.

‘This is the road you must never set foot on, for this is the road to Hell.’

They ride on and on and come to a great orchard and Thomas asks to be let down so he can have an apple or two for he is hungry and the apples look very fine to him. The Queen tells him he cannot touch them for they are the apples that are made of the curses that fall on the earth in one day. They ride on and she reaches high up into one particular tree and plucks him an apple. She gives him the apple, saying, ‘It will give to you a tongue that will never lie.’

And this is how he got the gift of prophecy. They ride further on and at last come to a great and beautiful valley which she tells him is Elfinland. Thomas lived here for seven long years, after which he returned to earth and became a great prophet. It is said that among other things he foretold that the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean would one day meet through Scotland, and this is taken to mean the Caledonian Canal. Many and varied are the prophecies and rhymes from all over Scotland attributed to Thomas after his return from Elfinland, but a few years later the following is said to have occurred.