8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

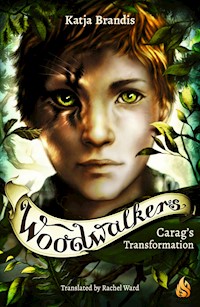

- Herausgeber: Arctis US

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: The Woodwalkers

- Sprache: Englisch

At first glance, Carag looks like a normal boy. But behind his shining eyes hides a secret: Carag is a puma shapeshifter and has only recently started living in the human world. Half human, half mountain lion, Carag grew up in the wilderness of the Rocky Mountains. He can't help but wonder what life as a human would be like even though his curiosity divides him with his family of mountain lions and puts him in great danger. When he finds out about a secret boarding school for Woodwalkers like him, that he felt a sense of home. He makes friends in Holly, a cheeky red squirrel, and Brandon, a shy bison. And Carag can really use it - because the world of Woodwalkers is full of puzzles and dangers . . .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 311

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Katja Brandis

Woodwalkers

Carag’s Transformation

W1-Media, Inc.

Imprint Arctis

Stamford, CT, USA

Copyright © 2023 by W1-Media Inc. for this edition

Author: Katja Brandis

Original title: Woodwalkers. Carags Verwandlung

Cover and illustrations by Claudia Carls

© 2016 by Arena Verlag GmbH, Würzburg, Germany.

www.arena-verlag.de

First English-language edition published by W1-Media Inc./Arctis, 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronoic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without

the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

The Library of Congress Control Number is available.

English translation copyright © Rachel Ward, 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

ISBN978-1-64690-620-8

www.arctis-books.com

For Robin

Mystery Boy, they call me; the newspapers and TV stations are all talking about me. I’m the mysterious boy who appeared out of the woods one day: “Nobody knows who he is. He doesn’t even know his own identity. He has completely lost his memory.” In reality, my memory is perfectly fine, and I remember everything. Including, of course, the very special, momentous day when I was first allowed to walk among the humans . . .

Human Amazements

On soft paws, we padded through the pine forest, my mother, my big sister, Mia, and me. I was so excited—it was like having ants under my fur.

And we’re really doing this? I asked my mother for the umpteenth time, the thought passing soundlessly from my mind to hers. We’re going into the town?

My mother snorted. If you ask again, we’ll turn right back!

Of course, she was on edge. We’d spent the last few weeks constantly begging her to take us along, so that we could see it all for ourselves, at least once. We were no longer satisfied with just hearing stories about the humans.

Soon after that, she paused and began digging in the dirt with her claws out, as if she were hunting gophers. Our stash of human things must be around here somewhere, she told us, and soon we saw something silver glitter under her paws.

She nodded with satisfaction and began to transform. Her body straightened, her hind paws became feet, her front claws elongated into fingers, her sand-colored fur vanished from her body. Now she had long, sun-bright hair that fell all the way down her back. When she smiled at us, we saw her ridiculously tiny human teeth.

“Okay, your turn now,” she said in her high human voice. “You guys remember what to do, don’t you? Concentrate. Think about what your other form looks like. Feel it within you. Can you feel the tingling?”

Mia shook her head grimly, which looked pretty silly in her puma shape.

But I managed well; moments later, I was standing there on the forest floor, feeling the pine needles prick my bare feet. I jumped up and down, laughing, just to test how it sounded again. It was great to have hands—you could do so much with them. I’d almost forgotten what that was like; we didn’t change very often.

“Come on, Mia! You can do it!” I encouraged my sister. “Or you won’t be able to come!”

“Stop bugging her,” my mother said. “You’re just making it harder for her.”

I waited impatiently, then used those incredibly useful human hands to keep on digging up the stash. It consisted of a battered tin box buried deep beneath the forest floor.

Finally, my sister had changed, too. Her brown hair was sticking up as if she had a porcupine on her head. Combing it with her fingers didn’t help much.

Mia fell to her knees beside me and, together, we pulled the lid off the box. Solemnly, my mother pulled some things out and handed them to us—long pieces of cloth, angular pieces of cloth, longish, hollow things made of leather. I’d completely forgotten what to do with that stuff.

My mother smiled again. “Carag, that doesn’t go on your head. It’s a pair of pants—you have to put your legs in the holes!”

“Why didn’t you say so?” I muttered, trying again.

Once we’d all managed to get dressed, I cast another curious glance into the tin. There were all kinds of packets and bottles—human medicine. And a couple of crumpled, greenish pieces of paper.

“What’s that again?” I asked.

“Money,” explained my mother. “Dollars. We can buy things with them.” Delicately, she picked up one of the bits of paper with a five on it and stored it inside her clothing. Then she looked seriously at us. “Okay, let’s go. We’re only going to the town once, so have a good look around. But you mustn’t change there, that’s important! They mustn’t notice who we are. Got that?”

My mouth had gone dry. “What if, if . . . they do notice?” I asked.

“Then they’ll kill us,” my mother answered curtly.

Oh. Mia and I looked at each other. Were my eyes as large and scared as hers?

Finally, we set off on our way. We probably looked terrible. Our clothes were as out of place as a fish up a fir tree. My long pants ended halfway down my shins and my T-shirt was faded, not to mention stained. We must all have had pine needles in our hair and mud on our hands.

Whatever. If people stared at us, I was way too excited to notice. So many humans! And all those gleaming, colorful cars, which stunk so bad when close up! But the shops were even more intriguing. Almost as soon as we reached the main street, I pressed myself up against the nearest window. There were hats for sale, stones—who in the world bought stones?!—clothes, cups with pictures on them, more clothes, and food, which smelled delicious.

“Soft-serve ice cream,” I read the sign beside the shop. “Vanilla, strawberry, and chocolate.”

My mother had taught me to read, but she’d never told me what soft-serve ice cream was. The sweet, creamy scent filled my nose, and a growling and rumbling started somewhere in the vicinity of my belly button. Hey, hang on a moment, what was my stomach up to? But the smell wasn’t even the worst thing. To my horror, I felt a tickle as fur started to grow beneath my T-shirt. Oh no, stop, not now!

Quickly, I closed my eyes. I’m a human, I’m a human, I thought until the fur had shrunk back to short stubble and then vanished altogether. Phew. My knees felt soft and trembled with shock.

“I’ll buy you each an ice cream,” my mother said. With a flourish, she pulled out the tattered bill with the five on it and handed it to a stranger. “One chocolate, one vanilla.”

The woman gave her some clinking pieces of metal in return and handed me something that looked like a heap of bear poop. Whatever, just try it, I thought and touched the cold brown stuff with my tongue. A wonderful, sweet taste filled my mouth. If bear droppings had tasted like that, I’d have tailed every single bear until it had to go.

Mia was given the vanilla one and she sighed with happiness. But, at the same time, she seemed uneasy and kept looking around. No wonder—there were so many humans all around us as well as all the unfamiliar smells and sounds.

We passed a shop with glass doors, through which we could see all kinds of interesting things inside: SUPERMARKET, it said.

“I want to go in there!” nagged Mia, and I joined in the begging excitedly, until eventually my mother nodded reluctantly.

“All right, then, but not for long.”

The glass doors made way for us, and Mia and I looked around in disbelief. Food, food everywhere! Mountains of food!

“Galloping gophers,” I breathed, almost involuntarily. “And the humans can just pick all that stuff up, even in winter?”

“Even in winter,” my mother confirmed, and Mia and I groaned with envy. In winter, we were often hungry because it was much harder to kill a wapiti or a bighorn sheep.

Shocked, I saw that my sister had partly changed from sheer excitement. Her lips barely fit over her fangs and she hadn’t even noticed. She was in the middle of pulling a can off the shelf, perhaps because it had a picture of a cat on it and the cat looked a bit like us. Mia used a fang to bite a hole in the can and sniffed at the contents. “Hey, you can buy roadkill in tins!” she announced, as we walked on.

I tugged at my mother’s sleeve, but she was busy picking up some of the metal money discs that had dropped out of her pocket.

My sister was still holding the busted can in her hands. “Get ahold of yourself and put that thing back,” I hissed at Mia, and she snarled at me quietly. Then she raised her head to sniff.

“Something here smells so good, don’t you think?”

A man in the supermarket was helping my mother pick up the money. Resting on his nose was a frame holding two shiny circles, and there were metal things in his ears. For a moment, I forgot the problem with my sister and stared at the guy in fascination. He smiled.

“Hey, kid. What’s your name?”

“Carag,” I said, looking up at him.

“D’you like it here in Jackson Hole?”

“I sure do!” I said, and the man laughed and gave me a round object that crackled in my hand. The thing smelled good and I popped it in my mouth. Now the man was laughing even more.

“You might want to unwrap the candy first,” he said helpfully. Then he waved and went back to work.

How nice these humans were! And how powerful they must be: to build a thing like this, this town full of wonders. What must it be like to be like them? To live like them?

Sadly, the candy only tasted of rotten fruit. I spat it out on the floor when no one was looking.

“Mia!”

At the sound of my mother’s frightened shout, I forgot every thought of humans and whirled around.

Mia’s face was covered with pale brown downy hair. An icy feeling trickled through me. She was changing back! Could she still stop it, like I’d done earlier?

My mother pulled her down an empty aisle, grabbed a packet of food that showed a laughing woman and held it in front of my sister’s eyes.

“Mia, sweetheart, concentrate. You look like that. You have to stay like that. Imagine looking that way. Imagine it really hard, okay?”

Mia nodded obediently, and to my relief, I saw her canine teeth shrinking again. A bit, at least.

But then she sniffed again and fixed her eyes on something at the end of the aisle.

“Oh no, the meat counter!” my mother muttered. And Mia was already racing away, suddenly in her puma shape—her sleek pale brown body barely seemed to touch the floor. In two bounds, she’d reached the meat counter and was fishing over it with her paw. Soon she had a steak hanging from each claw.

Customers were scattering in all directions, screaming and pointing flat, rectangular things at Mia. Were they trying to kill her? Somehow I managed to stay in my human form and dashed as many of those things as I could out of people’s hands. There was crashing and clattering.

“No, Carag, don’t!” my mother called, running after Mia, who was trying to climb onto a shelf labeled BREAKFAST CEREALS so that she could get high enough to eat her prey in peace. But my sister couldn’t get a grip on the shiny shelf, and it began to sway under her weight. She slipped and crashed to the floor amid a shower of cardboard boxes. For a moment, you could barely see her under the heap, with only her lashing tail peeking out. More people were running for the exit, shouting.

It was kind of neat how scared they were of us. It made me wonder why on earth were we so scared of them.

“We’ve got to get out of here, right now!” my mother hissed, as I picked up Mia’s clothes. “They’ll be here with guns in a minute!”

“Guns?” I asked anxiously. I didn’t know exactly what that meant, but it didn’t sound good.

Mia was just clawing her way out from under the boxes. She was chewing on a piece of beef and looked cheerful, despite being covered from top to toe in multicolored cereal. My mother grabbed her by the scruff of the neck and gave her a shake.

“Quick, we’ve got to get out of here,” she ordered, and the three of us ran for it.

But it was too late. The entrance was already being guarded by burly men in black uniform shirts—they didn’t look like they’d let anything on four legs through. My mother covered us while Mia and I slipped behind a shelf.

“You’ve got to change back,” I whispered desperately into her furry ear. “Come on, try! Please!”

A few breaths later, a human girl was sitting beside me again, combing her hair with fingers that still had needle-sharp claws.

“I’m so sorry,” she said, looking a bit down.

“You could have at least left some for me,” I complained, as I pushed Mia’s clothes over to her: they had fallen off as she’d changed.

“Quick, we have to scream and run out, just like everyone else,” my mother said, as soon as Mia had gotten dressed again.

That worked perfectly—the people in uniforms didn’t give us a second glance. Even though Mia had forgotten to hide her clawed hands in her pockets.

Utterly exhausted, our feet shredded by those painful, unfamiliar shoes, we limped back to the forest.

My father was not exactly thrilled when we told him what had happened.

“At least the humans didn’t hurt us,” I said, as he looked at me disapprovingly in his puma shape. “They were nice to us! Well, they were until Mia started plundering the meat cooler.”

He spat at me. Nice? They’re cunning and dangerous! His voice cut through my head. We have to keep away from them! He turned his bad temper on my mother. Was there really any need for this whole business in the town?

If we’d forbidden them to go, they’d have gone in secret, my mother answered, just as irritably.

To my sorrow, I realized that I was already yearning to go back to that astonishing place, where there was so much to discover. Why can’t we shape-shifters live as both, as humans and as pumas? I ventured to ask. Sometimes one thing, sometimes the other?

You need a whole lot of paper if you want to live as a human, my mother tried to explain. Paper that says who you are. We don’t have that stuff.

My father looked at me with his golden cat eyes; his gaze went through and through me. You have to choose one, Carag, he said. Doing both is impossible.

Of course, my mother had no intention of taking us again. Disappointed, I often spent half the night watching the glittering town lights from high up in the mountains—they were so much brighter than the stars. But I couldn’t help myself. Six months later, I slipped down there alone for the first time while my parents were out hunting. I wandered the streets, smelled a thousand new, exciting smells, and wished I could have a ride in one of those things my mother had called cars. I’d barely gotten back before I was longing to go there again.

Two years later, at the age of eleven, I made up my mind. But not the way my family would have liked.

I want to go to the humans and to live like them, I announced one morning, after we’d licked the dew off our fur.

The rain got into Carag’s head, Mia teased, cuffing me with retracted claws.

I took a deep breath, concentrated, and changed into a human. At once, I missed my fur—the cold, damp wind was not very pleasant on my bare skin. “I wasn’t joking.”

My father had flinched when I suddenly shifted. Discombobulated, he stared at me in my human shape. My mother seemed alarmed, too. But . . . that’s not possible! How are you going to . . . ?

“I know exactly how to do it,” I said. I’d been working on my plan for weeks. “I’ll take my things from the cache and . . .”

Forget it. You belong here, my father’s voice growled in my head. His furry ears twitched in agitation. Now stop all that nonsense; we’re going hunting. I’ll teach you how to kill a wapiti.

Xamber, I think he means it. My mother was studying me in concern. Did she think I was too young to leave? But I was eleven, and she’d told me herself that shape-shifters could be independent sooner than humans! If I’d been a true puma, I’d have gone my own way years ago.

I’ll come back and visit you, I said, feeling simultaneously excited and downcast. As often as I can.

Go and do it, if you want to, my father spat. But I’m telling you now—we want nothing to do with humans!

It was my turn to look shocked. “But even if I live as a human . . . I won’t be one. I’ll just be pretending! I’ll always be me, even if I look a bit different.”

Carag, do you really want to go there all by yourself? My mother sounded helpless. If you choose your second shape, we won’t be able to stay close to you. We might not be able to see each other again for a very long time. You know that humans don’t tolerate predators close to where they live.

“You could change, too, just now and then,” I suggested, desperately . . . and I felt even more desperate when I got no answer. Even my mother turned her head away. She didn’t trust humans much, either, and only ever changed reluctantly.

It’s a really dumb idea! Mia snuggled up to me, rubbing her soft head on my bare legs. She looked confused and unhappy. Don’t you like it here in the mountains?

“Yes, of course, but . . .” My human eyes welled up. Being a puma wasn’t enough for me. But that was so hard to explain.

We won’t be able to be there if you need us, my mother repeated sadly. I was half expecting her to change, to show me that she, too, was partly human and had some kind of understanding of what was going on inside me. But she stayed in her puma shape.

“I’ve got to go now,” I said, hugging Mia and then my father, wrapping my arms around their furry necks and pressing them to me; then I did the same to my mother. Take care of yourself. Her voice in my head sounded sad. My father didn’t move when I hugged him, and he didn’t look at me.

Would he truly cast me out? No, surely not! He was furious right now, but he’d cool down, I was sure of it.

I was beat, trembling with worry, but very determined, as I fetched my clothes from the hiding place. In human form, yet barefoot, I walked down the valley and crossed forests and clearings until I saw the first buildings. I simply walked up to the Jackson police station and knocked on the door. I claimed not to know who I was or where I’d come from. My plan worked. They took me for a human and gave me all the papers I needed.

I’m thirteen now, they call me Jay, and I’ve been in the seventh grade at Jackson Hole Middle School for a few weeks. It’s taken until now for me to start because I had to learn tons about the human world first, so I was homeschooled by my foster family.

With my short sand-colored hair and green-gold eyes, I don’t stand out at school. I wear jeans and sneakers and carry a backpack like any other student. Almost everyone here has gotten used to me by now.

Almost everyone.

And sadly, I was wrong to think all humans are nice. Some people at school make mean remarks about me when they think I can’t hear (I can—their whispers are pretty loud to shape-shifter ears). And others are even worse—they’re about as nice as a rabid pika. Especially Sean, Kevin, and his girlfriend, Beverly, who were waiting for me outside the school on that September day when everything would change. Waiting with strange grins on their faces.

Trouble

Kevin was one of the strongest boys in the school and truly enjoyed tormenting others. His girlfriend, Beverly, longed to be a cheerleader but she had no rhythm. So she had no chance. Maybe that was why her favorite activity was belittling other people. And Sean joined in because he had nothing better to do.

The three of them were looking at me like I was their prey. I felt a bit like a prey animal, too, which I didn’t much like. In my first two weeks at middle school, the three of them had left me alone because there were too many people watching out for me. But the grace period was over now. They’d pushed me once or twice, tried to trip me up, and smeared paint on my jacket. They called out dumb insults as I passed and found themselves hilarious even though I always pretended my ears were made of stone. Nobody ever stood up for me, and that made me a bit sadder every time.

On this particular day, I was looking around for a way out but the three of them had me surrounded. None of the other students was paying attention to us: the chic girls and cool guys were all heading for cars and school buses.

“Hey, Jay?” Kevin asked, coming closer while Sean closed in from behind.

“Leave me alone,” I told them.

“Oh, c’mon, Mystery Boy,” said Kevin, raising his fist as Sean grabbed my arm. “We only want to play.”

“I don’t know any games where you punch yourself in the belly.” By the time Kevin’s fist landed, I was elsewhere. Sean stared at me as the blow landed on his stomach and gave a faint oof.

Not that that fazed Kevin: in two steps, he was right back up to me, trying to get me in a headlock. This wasn’t funny.

“Stop that. I can’t breathe,” I complained.

“That’s kind of the point,” said Kevin, and Sean giggled.

Okay, enough. Lightning fast, I slipped out of his hold, grabbed Kevin from behind, and hurled him to the ground. A moment later, Sean was off his feet. I didn’t want him to fall too hard, so I dropped him right onto Kevin.

Now I could finally walk away. Or so I thought. But then there was a splash! A bucket of ice-cold water landed on my head, ran down me, and flooded my shoes.

I’d forgotten Beverly.

Water! They couldn’t know it, but I loathed the stuff. Humiliated, soaked through, and leaving a dripping trail behind me, I walked away while the others’ laughter rang in my ears. My eyes were burning and my heart hurt. I wished I could hide away somewhere, feel sad in peace. Why couldn’t these people just accept me the way I was? Why did they find it so much fun to hassle me?

A raven was hopping around on a fence beside me, cawing and spreading its wings. I glanced over at it and walked on, almost stumbling over a second raven that was strutting ahead of me. It tilted its head and looked at me with clear black eyes.

I stepped around it and sank back into my gloomy thoughts. I’d imagined school very differently. More fun. I did all right in class—most of the teachers liked my curiosity and that I was really trying hard to catch up. But sometimes I wondered exactly why I needed to learn algebra or music theory. And I hadn’t made any friends yet. Was that because pumas were loners? Or had I made an idiot of myself too often? The thought made me even sadder. And these ravens were getting on my nerves. What did they want? One of them was trying to sit on my shoulder.

“Beat it—I’m not a chair,” I muttered, slouching over to the old mountain bike my foster family had given me. All right, the ravens were finally flying off.

Maybe I ought to try to get onto the football team. Everyone liked the football stars. And movie stars. They liked movie stars, too. But I’d only been on TV once or twice—that didn’t count.

Some people were real celebrities, like the man whose face was on a poster hanging on the school fence, advertising an event. He was a VIP named Andrew Milling. You heard about him everywhere and I’d seen him on the news, too. Probably everyone wanted to be his friend.

Dripping, I climbed onto my bike and cycled “home”—to my foster family, the Ralstons. Their black Labrador, Bingo, was running around in the front yard. When I parked the bike, he bristled and barked at me, like he did every day. I guess he didn’t like predatory cats.

I ignored him as usual and, once inside, crossed the kitchen, hoping I could creep up the stairs to my bedroom. But I wasn’t quick enough.

Donald, my foster father, was a psychologist, and there was a connecting door between his clinic and the rest of the house so that he could pop through for coffee. As he was doing when I walked in.

“Hi,” I said despondently.

“Hey, how’s it going, my boy?” Donald asked with a paternal smile, putting his arm around my shoulders. But only for a second. He snatched it away. “Jeez, Jay! Why are you so wet? My sweater! I’ll have to change, and my next patient’s due in five minutes . . . You need to get changed too—go on, take a shower, and be quick about it!” With that, he left.

My little foster sister, Melody, was playing with toy horses on the beige carpeted stair. “Don’t step on them!” she said when she saw me.

For a change, there was no heavy metal droning from my foster brother’s room. A lucky break! I passed Marlon’s door . . . and at that moment it was yanked open. A brutal sound wave crashed over me. I nearly hit the ceiling with shock and Marlon—remote control in hand—doubled up with laughter.

“Yeah, that was good. Do that again,” he grunted.

I looked daggers at him, walked into my room, slammed the door, changed into dry clothes, and threw myself onto the bed. Maybe being a human hadn’t been such a good idea after all. It had been a lousy idea! There were no teachers up in the mountains, trying to stuff useless human knowledge into my head. And no idiots who wanted to beat me up. Life as a puma had been good. Why had I given it all up?

Every time I thought about my family, it felt like some small animal was gnawing at my heart. Eighteen months back, I’d tried to see them all again. But they hadn’t been there. They’d just left their den. Because of me? Or had something happened? They could be somewhere else, somewhere in the mountains, hundreds of miles away! I had no idea how I’d find them again, or if they’d forgive me.

Besides, it was fall already and soon it would be winter—it came early here in the Rocky Mountains. Sure, a fully grown puma can survive a winter in the mountains by himself. But I wasn’t fully grown. And besides, there was another teeny-tiny problem . . .

Before I could think any further, I heard quiet steps on the landing and a knock on my door.

I already knew who it was and had to smile, whether I wanted to or not.

My foster mother, Anna, came in and sat beside me on the edge of my bed. She smiled at me in the way that always gave me a warm feeling around my heart.

“Hey,” she said, stroking a strand of hair off my forehead. “Had a bad day, huh?”

I nodded. I wanted to say something, but I couldn’t manage it.

“Trouble with the teachers? Was there something you didn’t understand?”

I shook my head, and Anna looked like she was proud of me. She worked in Child Protective Services and had suggested taking me in the moment I turned up at the police station, shy and in rags. She’d been incredibly patient as she’d taught me everything a human my age ought to know—whose head is on a quarter (George Washington), what the Internet is (a place for looking at cat videos), how to write an essay (with a pen and way too many words), and what you need cell phones for (everything!).

At first, Melody had been curious about me, but then she started to resent her mother spending so much time with me. Since then, she’d been treating me like a tick in her fur. Not that she had fur.

“Do they give you a hard time?” Anna wouldn’t let it go. “Give them a hard time back.”

“I do,” I said, staring past her at my poster of the Grand Teton mountains—rugged white peaks, shimmering mountain lakes, dark green forests. “But I’m just too different. Nobody wants to be my friend.”

“You’re different, that’s true. So?” Anna looked at me fiercely.

I buried my face in the pillow. She didn’t even know how different I was. Were there other shape-shifters, apart from me and my family? I’d never met any. Maybe my parents, my sister, and I were the only ones in the whole world.

Anna stroked my shoulder a while longer, then she sighed and left me alone.

I lay there—until I heard a sound and looked up.

There was a small animal at the window. A squirrel. It was perched on the window ledge, standing on its hind legs, front paws pressed against the glass. Now it was staring into the room at me. I stared back, and then the squirrel started dancing around on the ledge. What on earth had gotten into the animals lately?

I rolled my eyes, linked my arms behind my head, and started thinking about my life again. And about the problem that prevented me from just going back to the mountains: my parents had taught me some of what a predator needs to know before I’d left them. But, unfortunately, not the most important thing of all.

I didn’t know how to kill.

Oh, I can learn that, I told myself, trying to be positive. Jump on the deer, bite into its neck, and done. Just a matter of practice.

Even the thought made me feel sick. I’d gotten used to taking steaks from a plastic packet, dropping them into the pan, and devouring them with a knife and fork. And served with herb butter, of course.

My sister, Mia would have laughed herself silly at me.

Whatever. Killing was a matter of practice—and I’d start right away. Tonight, I’d show them what I was made of!

Pretty Dangerous

Impatiently, I waited for darkness. Once everyone in the house was asleep, even the irritating family dog, I transformed in my room. It was a glorious feeling to be a puma again. A mountain lion, king of the forest. My muscles felt like coiled steel springs as I hopped up onto the windowsill and balanced there until I was certain that there was no one nearby. Then I leaped down onto the lawn from the second floor and flitted through the yard, behind which the forest began. It was a moonless night, but my feline eyes could detect the starlight. The night air smelled of freedom, and in the distance, I could make out shrill, squealing roars. There were clearly loads of wapiti bulls nearby for me to practice on.

Before long, I’d found three of them—two females and a bull—looking very appetizing as they grazed in a clearing. Somewhat closer to the campground than I really liked, but if the campers asked nicely, I could always save them a piece of meat.

Now it was time to hunt them, the way my father had taught me. Cautiously, I crept, no, stalked forward—I was a dangerous predator, after all!—one paw at a time, never once taking my eyes off the wapiti. Perfect posture, low to the ground, loose shoulders, ears pointed to the front.

One of the wapitis raised its head. Had I made a mistake? Had I forgotten to pay attention to the wind direction? No, definitely not.

Only twenty yards . . . time to spring now. Now!

I sprang. But not very far. Some mean, thin thing had been in the way of my front paws and it had sent me somersaulting. I crashed onto my back on the grass and rolled a bit farther on. Grumpily, I picked myself up and looked to see what it had been. Oh, for the love of mackerel! I’d tripped over a stupid guy rope!

The puzzled wapitis looked over at me. Then they snorted, loped very slowly away, lunging out a couple of times and showing me their white rumps. They were doing that on purpose—they were laughing at me! They’d probably found my somersault hilarious!

I felt insulted, wanted to chase them, to show them what happens to animals that make fun of a puma. But then I heard a rustle, and I suddenly realized that a guy rope is generally attached to something. Otherwise, it’d be called something else. Just a bit of string, for example.

Someone crawled out of the rectangular, dark thing on the other end of the rope, very close to me. The stench of fear was so strong you could probably smell it from miles away. The human was frantically feeling around for something. Probably a flashlight. Humans might rule the world, but they had lousy night vision couldn’t see a thing without light.

But that wasn’t the worst part. The worst part was that there was now more rustling behind me, in another tent.

“Hugo, what are you doing? What’s all that racket?” scolded a voice that sounded like a mother yelling at her son.

Steps were coming closer from the other direction. I was rooted to my spot in shock. It was like I’d been stuffed, and I didn’t know which direction to flee.

“Um,” said a voice that sounded very young and very scared. “Mommy . . .”

“Nobody can sleep through all that noise!”

“Mommy . . .”

“Yes, what is it?”

“It wasn’t me. Making the noise.”

“Hugo, you know better than to lie to me!”

More rustling. Someone had emerged from the tent. Then a sound filled the clearing. “Aaaaagh! A bear!”

Sure, I wasn’t a bear, but they clearly meant me. I panicked and ran but unfortunately headed in the wrong direction, almost crashing right into Hugo’s mother. At the last moment, I swerved, but my tail hit the woman’s legs, sending her flying, and she screamed. My eardrums were splitting! Flashlight beams were flitting over the undergrowth and my fur. If these people had paid any attention at all in biology, they’d know by now that they’d been wrong about the “bear.”

I had to get out of there! There’d be no more deer that night because everyone in the area, from the chipmunks to the bison, would know I was here now.

I ran in huge bounds, while all around me, people were crawling agitatedly out of their tents, panicking, trying to climb trees. With pathetic results.

A guy started throwing stones at me and hit me right on the muzzle. And suddenly, two suns lit up the darkness, dazzling me: a huge car engine roared. That was all I needed! What were they planning? Did they want to run me down? Help! Which way was out? I didn’t know, but I had to get away! Go, go, go! Just get away!

I leaped up onto a laundry hut and down the other side. I could hardly believe it, but my path was clear now. A moment later, I was alone in the pitch-black forest, running until the noise of the car and the screams had faded behind me. Until my tongue lolled out onto my chest—or at least that was how it felt.

I was overjoyed when I got back to the Ralstons’ house and I could leap up to my bedroom window and safety.

The very next day, my experiences were in the newspaper. I saw the headline at once:

Puma Attack on Campsite

Hugo S. (11) and his mother, Michelle S. (41), from Chicago, had a narrow escape from a frenzied mountain lion. “I was scared to death,” said Michelle.