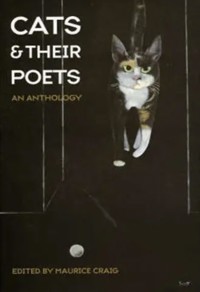

Cats and Their Poets E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Cats are universally revered, worshiped and feared, evoking love and fascination in their hosts and companions. This delightful anthology of poems about cats, from the eighth-century Pangur Ban to the present, encompasses both the arcane and the familiar, the simple and the satisfyingly subtle. Cats and their Poets contains work by seventy-five writers, from Philip Sidney, Christopher Smart, Cowper, Keats, Rosetti, Dickinson and browning, through to Yeats, Don Marquis, Strachey, Sackville-West, Graves, MacNeice, Stevie Smith, Gavin Ewart, Hughes, Gunn, Silkin, Longley, Mahon, Ni Chuilleanain, Thomas Lynch and Vikram Seth. There are translations from Heine, Baudelaire, Verlaine, Mallarme, Valery and Apollinaire. These wonderful poems, selected and introduced by one of Ireland's most respected men of letters, say as much about their enigmatic creators as they do of their mysterious muses. They will surprise, illuminate and comfort the reader in equal measure.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 111

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2002

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CATS & THEIR POETS

INTRODUCED& CHOSEN BY MAURICE CRAIG

LILLIPUT MMII

In memory of Mephisto,Ramelek,Pyramus and Pidge,and in celebration of Minna

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Pangur Bán, Anon

The Nature of the Creature, Geoffrey Chaucer

The Rat’s Strong Foe, Sir Philip Sidney

An Appeal to Cats in the Business of Love, Thomas Flatman

Epitaphium Felis, John Jortin

The Poet’s Lamentation for the Loss of his Cat, which he us’d to call his Muse, John Winstanley

Lisy’s Parting with her Cat, James Thomson

On the Death of a Favourite Cat, Drowned in a Tub of Gold Fishes, Thomas Gray

from ‘Rejoice in the Lamb (‘Jubilate Agno’), Christopher Smart

The Colubriad, William Cowper

An Old Cat’s Dying Soliloquy, Anna Seward

from The Kitten, Joanna Baillie

To his young son Carlino in Italy, from England, WalterSavage Landor

To a Cat, John Keats

Mein Kind, wir waren Kinder, Heinrich Heine

Lines on the Death of a College Cat, Frederick Pollock

Cats, Charles Baudelaire

Cats, Charles Baudelaire

The Cat, Charles Baudelaire

Cat, Emily Dickinson

On the Death of a Cat, a Friend of Mine aged Ten Years and a Half, Christina Rossetti

Sad Memories, C.S.Calverley

Last Words to a Dumb Friend, Thomas Hardy

Cat and Lady, Paul Verlaine

Connoisseurs, D.S. MacColl

The Cat and the Moon, W.B. Yeats

A Cat’s Example, W.H. Davies

White Cats, Paul Valéry

Double Dutch, Walter de la Mare

Five Eyes, Walter de la Mare

Lost Kitten, Robert Service

The Tom-Cat, Don Marquis

The Song of Mehitabel, Don Marquis

The Old Trouper, Don Marquis

A Cat, Edward Thomas

Milk for the Cat, Harold Monro

The Cat, Lytton Strachey

‘Je Souhaite dans ma Maison’, Guillaume Apollinaire

On a Cat Aging, Alexander Gray

On Maou Dying at the Age of Six Months, Frances Cornford

from The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock, T.S. Eliot

On the Death of a Much-Loved Kitten named Sam Perkins, HowardPhillips Lovecraft

Ballade of the Cats of Bygone Time, ‘Michael Scot’ (Kathleen Goodfellow)

The Greater Cats, Victoria Sackville-West

War Cat, Dorothy L. Sayers

Cat-Goddesses, Robert Graves

Quorum Porum, Ruth Pitter

Cruel Clever Cat, Geoffrey Taylor

The Lost Cat, E.V. Rieu

‘She Cannot Read’, Francis Stuart

‘A Sleeping Shape lies on the Bed’, Nerissa Garnett

The Singing Cat, Stevie Smith

Monsieur Pussy-Cat, Blackmailer, Stevie Smith

My Cat Major, Stevie Smith

Diamond Cut Diamond, Ewart Milne

Cat, Cecil Day-Lewis

Cats, A.S.J. Tessimond

The Death of a Cat, Louis MacNeice

Black Cat in a Morning, Norman MacCaig

Old Cats, Francis Scarfe

My Old Cat, Hal Summers

The Family Cat, Roy Fuller

In Memory of my Cat Domino: 1951–1966, Roy Fuller

from Lady Feeding the Cats, Douglas Stewart

Sonnet: Cat Logic, Gavin Ewart

A 14-year old Convalescent Cat in the Winter, Gavin Ewart

‘Jubilate Matteo’, Gavin Ewart

In San Remo, Charles Causley

‘Jeoffrey’, John Heath-Stubbs

Problem, Kenneth Lillington

Lines on the Death of a Cat, John Gallen

High on a Ridge of Tiles, Maurice Craig

Three Cat Poems, Maurice Craig

from ‘Other’, Fergus Allen

London Tom-Cat, Michael Hamburger

Odysseus’ Cat, U.A. Fanthorpe

Apartment Cats, Thom Gunn

Esther’s Tomcat, Ted Hughes

Of Cats, Ted Hughes

His Cat, Jon Silkin

My Cat and I, Roger McGough

Tam, Michael Longley

Autumn Blues, Derek Mahon

Cypher, Eiléan Ní Chuillenáin

Grimalkin, Thomas Lynch

The Stray Cat, Vikram Seth

A Cat’s Conscience, Anon

Index

Acknowledgments

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

The cat, as everyone knows, has a unique and complex relationship with man. Very generally admitted to our firesides, yet classified in law as animal ferae naturae, his place in human affections has varied, and still varies, very widely indeed.

I do believe that the essence of what happened is accurately conveyed in that magical fable of Kipling, ‘The Cat that Walked By Himself’. By the end of the tale a sequence of implicit bargains has been struck, and these remain in force. There is, however, in Kipling’s narrative one false note, or rather a moment in which the cloven hoof of the imperialist shows itself in a distrust of beauty and in the cult of ‘manliness’ which is such a marked feature of the Victorian ethic. ‘Three proper men out of five’, says Kipling’s Man, ‘will always throw things at a Cat whenever they meet him.’ To this day, in many quarters, it is thought or felt to be not quite masculine to be fond of cats.

Kipling sounds, in the story, another note which, if not false, is misleading. ‘I am the Cat’, he makes him say, ‘that walks by himself, and all places are alike to me.’ But, to the cat, all places are emphatically not alike, except in the sense that there are no places which are out of bounds, nowhere, however perilous, which he is not driven by his insatiable curiosity to explore. And having found a place or places to his liking, he will return to it or to them with inexhaustible persistence and guile.

I think that Kipling was right about the first reason for the cat’s reception into our houses and into our company: its therapeutic value in charming the baby by its fur and its purring and its playfulness, rather than by any more material services which it might render to its hosts. The ability to catch mice comes third in the diplomatic strategy of his campaign to secure entrance to the cave. That, I think, is how it really happened. Cats were family pets in ancient Egypt, as well as being sacred objects if not actual gods. Their utility in controlling the rodent population, though undoubtedly useful to the cultivators of cereals, is surely incidental.

‘I am not a friend, and I am not a servant’, says Kipling’s Cat. He says it very early on in the negotiations: in fact he says it when the Woman has said that, having the Dog and the Horse, she has no need of friends or servants. The Cat takes this at face value, but he keeps his counsel. That is the text which later peoples, less civilized than the Egyptians, have found hard to swallow. Many of the poems in this book are, in effect, variations on that theme.

It may as well be said at the outset that there have been cases of close and self-giving friendship and love between cats and human beings. It must also be said, in rebuttal of the widely held belief that cats cannot be trained to do anything which they do not antecedently want to do, that they can. The detailed and entirely convincing narrative of Anthony Hippisley-Cox, who trained a troupe of ordinary domestic cats to perform reliably in the ring, is in prose and so has, alas, no place in this book. I have myself seen, on a lonely farm in Brittany, three or four young lions being taught to jump over a placidly standing sheep. Hippisley-Cox once struck one of his cats, and it went on strike for five days (A Seat at the Circus [1951]).

There is not a great deal of evidence that the Greek or Roman poets set as much store by their cats as by, for example, their pet sparrows or, to be more precise, the pet sparrows of their mistresses. Catullus is silent on the cause of death of Lesbia’s bird. Perhaps the cat, if he were the culprit, succeeded in making himself scarce or even invisible. (If I were of a suspicious turn of mind I might speculate on whether ‘Catullus’ might be a diminutive of ‘cattus’ which was the demotic Latin for a cat. While verifying this I found a word ‘catillus’ which means a licker of plates … But I digress.)

Fifteen hundred years later, John Skelton was in no doubt about who killed his sparrow Philip, and devotes much of his poem to a recital of the horrible things which he hopes will be done to the cat. During the intervening centuries all too many of these horrible things were in fact done to cats, nor did this barbarity cease, nor is it even yet extinct.

The cat, like many of the rest of us, had a thin time of it during the Middle Ages. Almost alone in those dark centuries there shines out the anonymous Irish monk, who in the monastery of Sankt Paul in Carinthia in about the eighth century, wrote the famous ‘Pangur Bán’ (p.3). In this incomparable poem the author draws a parallel, by no means forced or far-fetched, which every writer will recognise, between the occupation of the sedentary scribe and of his guest. ‘Neither hinders the other, each of us pleased with his own art, amuses himself alone.’ It was to be a long time before any such sympathetic attempt to think one’s way into the cat’s mind was again to be made.

Geoffrey Chaucer disposes of the cat in six rather perfunctory lines about his practical utility, with no sign of affection or of close observation, and in another, rather obscure passage (in the Wifeof Bath’s Prologue) he seems to be referring to some kind of folk-belief or superstition. Superstition, and perverted religion, are accountable for those atrocities inflicted upon the cat in the following centuries, from which, in Lytton Strachey’s words, ‘shuddering History averts her face’.

From near the end of the Middle Ages there is an anecdote which seems to run clean counter to what might be expected. Hakluyt relates that an Italian ship’s cat was lost overboard but ‘kept herself very valuantly (sic) above water’ so that the master sent a boat manned by half a dozen men to rescue her almost half a mile from the ship. Hakluyt is surprised: ‘I hardly believe they would have made such haste and meanes if any of the company had been in like peril.’ Italians, he explains, value a cat as a good spaniel would be valued in England. But he suspects that the captain had a special fondness for this cat. Nearly two hundred years later Fielding records a similar incident, this time of a kitten, one of many, which, falling from the window of the captain’s cabin into the water, was rescued by the boatswain who swam back holding the kitten in his mouth, to all appearance dead. But while the captain was playing backgammon with a Portuguese friar, the kitten recovered, not entirely to the satisfaction of some of the crew who believed that drowning a cat was a good way of raising a favourable wind.

With the Renaissance comes the fitful recognition of the cat as an individual being. De Bellay loved cats and, in a poem nearly three hundred lines long, celebrated the life and mourned the death of his cat Belaud. Ronsard, on the other hand, did not care for cats and said so in an acid quatrain. Montaigne, their young contemporary, supplies the classic text on which so many variations have been played in the centuries since he wrote: ‘When I play with my cat, who knows whether she is amusing herself with me, or I with her?’

Sir Philip Sidney (p.6) shows some direct observation of how a cat ‘may stay his lifted paw’ while he is deep musing to himself. And at least Sidney hopes, or rather intends, that his cat shall have a long life. Shakespeare has very little to say about cats: Milton nothing at all. There are no cats in the King James Bible and very few dogs except those which ate Queen Jezebel (I Kings 20 v 23). According to Aubrey, Archbishop Laud was very fond of cats and imported, in 1637 or 1638, some tabby cats from Cyprus, which were sold at first for five pounds each. In time, says Aubrey, they ousted the English cats which, he says, were white with some bluish piedness. Certainly the cats have been hard at work ever since, mixing up the genes.

Thomas Flatman, a little after Milton’s time, observes the behaviour of cats and draws certain analogies between theirs and ours. There was to be plenty of that later on. But while, in the early eighteenth century, the number of cat-poems begins to increase, they are still, for the most part, little more than the incidental adjuncts to a polite scheme analogous to genre-painting or conversation pieces in which cats appear simply as decorative props. They are not individualised, nor, so far, is there any exploration of their mental processes. James Thomson, one of the first to put words into the cat’s mouth, (p.11) makes her (she is un-named except as ‘Puss’) express conventional regret at the loss of creature comforts and, we must concede, an instinctive sense of impending loss. The little girl Lisy, her owner, who is being sent away (presumably to boarding-school), makes a longer speech and dwells more on the affection between them.

John Winstanley, a Dublin poet and contemporary of Swift, takes up—unknowingly of course—the Pangur Bán theme, and in his elegy (p.9) for his (un-named) cat looks forward to W.H. Davies, two centuries later (p.43). The set-up is the same: poet and cat pursuing their respective preoccupations, with the cat providing solace or a solution to the ‘writer’s block’. Gray’s famous cat ‘the pensive Selima’ (p.13) is remarkable only for two things: for observing and admiring her own reflexion (which not all cats can do) and for losing her balance and falling into a goldfish bowl.

John Jortin, a mid-century Latinist, here rendered in the translation (p.8) by Seamus O’Sullivan, most movingly has his cat, speaking from the Elysian Fields, send a message of undying devotion across the waters of the Styx.

Then there is Christopher Smart. (p.15)