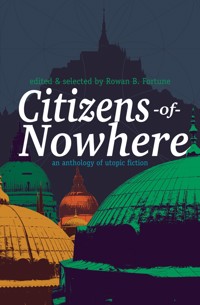

Citizens of Nowhere E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

"For me, to be a citizen of nowhere is to be uncertainly poised between those challenges [we face today] and a defiant hope that, five hundred years on from More's great contribution to literature, can rightly call itself utopian." from Rowan B. Fortune's Forward Thomas Moore's no-place that might be anywhere, anywhen, Utopia, has haunted our imaginations for over 500 years. Dismissed as a lost realm in this Age of Despair, Citizens of Nowhere offers route maps to this place where our ideals and our lives can coincide. Now more than ever, we need the hope of utopia. Citizens of Nowhere reminds us that it is never far away. Finding utopias within sci-fi, horror, romanti fantasy and modernist fiction, Citizens of Nowhere brings together stories from: Nina Anana, Fiona Ashley, Sonya Blanck, Rowan B. Fortune, Ben Jacob, George Lea, Greg Michaelson, Jez Noond, James Perrin, Diana Powell, Omar Sabbagh and Robin Lindsay Wilson.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Letters From Nowhere

A Snow Goose

K

The Ivory Tower

Notes on Housekeeping on Earth

Separate

For the Sake of Seeing

Without Fire

In the Stationary Cupboard

The Floating Market

By Herself

Somewhere In Brittany (Utopia)

Then and Now (Utopia)

Relief (Dystopia)

Eaters of Dreams

The Same Place As The Last

Biographies

Citizens of Nowhere:

an Anthology of Utopic Fiction

Rowan B. Fortune (ed.)

Published, in association with Rowan Tree Editing, by Cinnamon Press

Meirion House

Tanygrisiau

Blaenau Ffestiniog

Gwynedd, LL41 3SU

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2019 the authors.

Print ISBN 978-1-78864-094-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78864-115-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset by Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Adam Craig.

Cinnamon Press is represented in the UK by Inpress Ltd and in Wales by the Books Council of Wales.

Foreword

On October 5th, 2016, British Prime Minister Theresa May delivered a speech before the Conservative Party Conference. Here, she set out a withering critique of cosmopolitanism and outlined a deep seated, parochial nationalism. The speech included an attack on those who conceive of themselves as belonging to a community that is outside of the scope of a single place:

If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what citizenship means.

There is a tradition in literature, one recently celebrated for its five hundredth anniversary, which has questioned far more profoundly than May the idea of what citizenship means. The stories in this anthology stem from this tradition, and represent its great and imaginative diversity. Alfred North Whitehead once wrote: ‘The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.’ It could be said of utopia and its subgenres that it consists of a series of footnotes to Thomas More and his book, Utopia. For Utopia the novel can be read as dystopia, as satirical anti-utopia, as allegorical fable, as political treatise. And it can be read as utopia, as an exercise of fiction that seeks to realise the outlines of a better world. One that is, as its title—u-topia, no-place—suggests, nowhere.

My hope is that the short story I added to the anthology, ‘Letters From Nowhere’, serves as a route into the genre. It was written to be as much a commentary on utopia as a narrative belonging to it. I do not exactly outline an ideal society, although I hint at one. What I try to achieve, instead, is an outline of the ambivalent reasons we might read and write utopias. Including the wonderful example that follows my contribution. The mid-nineteenth century mystery of Sir John Franklin’s lost Arctic exploration is James Perrin’s point of departure. His eco-fable, ‘A Snow Goose’, imagines the discovery of an ideal community; in many ways it recalls the earliest utopias, whose authors were awed by the world’s scale and the possibilities of different ways of conceiving society. It is different to Jez Noond’s dreamlike ‘K’, set in a nowhere in every sense of the word—a place, a playground, obscured by time and therefore memory. Noond’s haunting story makes the reader assume the vantage of a waif with limited comprehension, truly lost in nowhere.

With ‘The Ivory Tower’, Omar Sabbagh adopts the perspective of Yussuf as a series of everyday encounters reveal the tensions in the man’s marriage; it is a story about one of the most utopian themes, the difficulties and struggles involved in human connections and relationships, the bonds that define societies. Diana Powell’s contribution is also enmeshed in everyday, recognisable concerns; she layers religious Millenarian dreams of paradise on top of a cultish, even dystopian community, and in so doing takes advantage of the short narrative form to provoke readers to consider the nature of our hopes for a better world. She exposes how such hopes can operate both as challenges to, and tools of, unjust power.

In ‘Separate’, George Lea conjures ‘that secret and forgotten place where we played, where we conspired, where we were never children.’ From this alternative and haunted topology, a parallel world, he unravels a metaphysical horror that disguises a transfiguration—Lea’s work demonstrates that utopia can find fertile soil even in genres more often conceived as anti-utopian, such as horror fiction. In the accompanying ‘For the Sake of Seeing’, Lea develops this further, introducing two enigmatic characters as they explore the ruins of a failed utopia that hides something more transgressive and more genuinely utopian. The themes and motifs of utopia can be as shocking as any in literature.

The conceit of Ben Jacob’s science fiction ‘Without Fire’ could operate as a meta-commentary on the utopia; it plays with ideas of authorial control and what real world concerns and anxieties motivate us to write such a work, to seek such an escape, in the first place. Likewise, ‘In the Stationary Cupboard’ by Greg Michaelson toys with the utopia’s preoccupation with paradisal visions of life after death, in the context of a historically familiar scenario: the interment camp and the failed radicalisms of a political upheaval. Michaelson’s story serves as a memento mori; from a place of seeming cynicism, it taps into the kernel of utopian hope and asks us to imagine a merely better world, rather than fleeing into fantasies about an altogether different one.

In Sonya Blanck’s ‘The Floating Market’, utopia is presented to the reader in an appreciation of beauty for its own sake in the midst of desperate scarcity, all in the context of a world that is only gleamed through impressions. Here, the gorgeous, crafted prose frames a contrast between the appreciation of life and the necessity of survival. Fiona Ashley takes a different approach to subverting the genre. Her prose has the quality of a fairytale, unadorned and at a remove from its protagonist; it’s a quality that fits the metaphysical drama and her ultimate, Kafkaesque twist. Ashley, like so many of the other contributors, is skilled at using the utopian prompt to comment meaningfully about what it means to be human.

As well as short stories, there are four microfictions in this collection. Three of them are by Robin Lindsay Wilson, and could aptly be called prose poems. Playing with the idea of utopia and dystopia, with elliptical moments, these pieces share with the broader genre preoccupations about time and meaning. Lea’s microfiction ‘Eaters of Dreams’ is a strange, inverted creation myth—taking the innocence of a prelapsarian idyll and turning it on its head. The collection finishes with another short story, Nina Anana’s ‘The Same Place as the Last’. It assumes a traditional utopian structure, a traveller to a better future whose impressions of it serve as a commentary on the present. This story thereby brings the classic conventions of the genre to timely themes of ecological catastrophe, far right populism and the refugee crisis.

The concerns of this final story, as well as those of the whole collection, show us how the utopia as a genre can still help us to grasp and frame the challenges we face, and to do so without forcing us to retreat into a useless cynicism. For me, to be a citizen of nowhere is to be uncertainly poised between those challenges and a defiant hope that, five hundred years on from More’s great contribution to literature, can rightly call itself utopian.

Letters From Nowhere

Rowan B. Fortune

Every time I pass the furniture shop down the main street in town I look inside the third window along, which contains a tableau taken from the life of some fictional person, the woman—or man, I guess—who is supposed to have configured this desk and bookshelf arrangement: its leather-bound volumes of the kind few people now own, and an old-fashioned map draped over the writing surface in all its poised clutter.

These are cues that are all chosen to suggest the life that the intended buyer should wish to live. I want another life, too; I want to be entirely somebody else and somewhere wholly other.

The nondescript cream envelopes were unstamped and unaddressed. They arrived at night, I think. Once I stayed up with Bernard dozing on my lap, flitting in and out of consciousness beside me. No letter arrived. At five in the morning, Bernard woke and barked, unusual for the old dear.

The regular mail only included a gas bill and a fifty per cent off menu items coupon for the new pizza place in town. A letter from nowhere—that was how I would come to describe them, thanks to Sayer—had not arrived through the mailbox, but when I went back upstairs one of those envelopes was waiting on my bedside table next to the tiffany lamp that Samantha bought me; that was where I would often put letters before reading them. It had materialised, as if from the ether.

The next day, the letter arrived as normal, sitting beneath the spam and official correspondence that the regular mailman dutifully delivered. It was like all the other letters from nowhere, including the one I had discovered on my bedside table. It started and ended the same as every other had.

Dear Carol,

…

Your doppelgänger from nowhere,

Carol

The sender wrote at length and created in her writings what I then thought to be an elaborate falsehood. And in her fantasy she and I were almost the same person, but whereas I inhabited a small bungalow and felt so completely alone, she inhabited this other world—the one I found so tempting, the one I craved. Most of her writings were about some fictitious nowhere that she had contrived and she traced in detail: the geography, governance, economy and architecture. She was exhaustive and meticulous and sometimes tedious.

In her fantasy the period she called ‘reified human history’ ended two and a half centuries ago, and this history corresponded closely enough, if not exactly, to our actual history up to around the year 1800. For over fifty days she expounded on eleventh century England, which she says is her speciality as a ‘historian of the reified human.’ Much of her exposition corresponded with what I read elsewhere at the time, checking her facts against those of agreed history.

After the end of rarified human history, my doppelgänger from nowhere tells me that there was a painful birth of a society rooted in the joys of what she called free labour. Humanity had been renewed and true human history begun. Humanity, she stressed with the repetitiveness of a religious mantra, had until then been alienated from itself. She gave numerous historical examples of such alienation from mass violence to awful working conditions. She had an almost monomaniacal obsession with the worst cruelties and would describe everything from the minutiae of tortures to the horrific deprivations.

For those hanged, drawn and quartered, the victim would be bound to a wooden panel, delivered by horse to the stage for the dreadful act. They were hanged, but not allowed to die of a merciful affixation. That way they could also have their external sexual organs removed—it was punishment reserved for men, whereas women would be merely immolated. They would also be disembowelled, beheaded and finally, literally, quartered; that is, chopped into four pieces.

Nor were her descriptions reserved for the distant past. Narrating a more contemporary war, she documented the lives of captives.

The smearing of human excrements on detainees’ bodies was not an uncommon practise. The shit would be pasted across their skin, left to mangle and matt with their body hair. It was either believed that valuable military intel could be gleamed from the humiliation, or, more likely, it was a method of relieving the abusers stress and channelling their complex moral and psychological traumas.

Everything in her fantasy, an alternative to the macabre portrait of our world, began from a different footing than it would in our reality. Education, childrearing, religion, work, culture, violence, law—it required, this other Carol enlarged, a way of thinking that would be alien to me. She would stress this in terms I found utterly, exhaustingly patronising.

I did not read every letter. In the early days, when I hoped they would stop and feared their daily arrival, it was my revenge to miss a series of them. They would appear and disappear every day. They could not be kept.

Nor could they be shown. Any attempt resulted in their prompt disappearance. I would leave them somewhere definite, on a table, tacked to the fridge, within my safety box, but they would be gone all the same. I would watch them through the whole of a night, and while the thick paper would remain, it would be blank. I would look at the words through the whole of the night, but at some point I would blink and, just as surely, the words would blink out of existence too. They existed only for me. And I assumed, were a product of my febrile mind. What I came to learn later does not clarify anything. I’m writing this only because it helps me to process what has happened, not because it helps me to understand.

It was a Sunday morning and I was having difficulty with the pain. I swallowed the eighteen pills, more than half of which were medication to counteract the symptoms of the other medication, a few of which were even medication to counteract the symptoms of the medication that counteracted the symptoms of the medication. I was the old lady who swallowed the fly—I would, and still will, die.

I took the pills with the coffee the beautiful Samantha—with her pixie cut of lush brown hair and her generous smile—made me every morning. She would arrive at eight, have my coffee and porridge to me by nine and then take Bernard for a walk; the old beagle did not need a long walk. At half-ten, she would check on me one last time and leave. On Sunday mornings my son, Joseph, joined my community-obsessed daughter-in-law. The puffy rings around his eyes growing more and more, so that he reminded me of a panda bear.

This was often all the human contact I had for months. Bernard helped to keep me sane. And the letters, however disturbing, did at least break the monotony. I resisted television, radio and the Internet, those passive entertainments felt like a surrender. I could no longer manage to read a long novel. I struggled to keep up with the stories. The letters, though, felt catered to my condition.

Back then, on good days, I could still potter about outside. And in the front garden I had a bench were I sat and read the other Carol’s missives when their content did not upset or bore me, and I chose to engage rather than ignore her horrors or tedious lectures.

If I had been younger—and healthier—curiosity would have propelled me sooner to research. Not only to investigate the content and claims of the correspondence, but the simple and impossible fact of magically appearing, magically disappearing, post. But I was neither. I could experience days without coherence, where thoughts would bleed into one another and the discomfort of wakefulness slid in and out of my delirious sleep. Grasping the reality of something so irreal, and doing so long enough to sustain curiosity, was a feat I only accomplished after seven months of receiving the letters.

At that time, I checked my emails about once a week on the old machine. I would wait for it to boot up, beeping, craning over my bedroom desk, against a window, looking out across the various striking blues, yellows and reds of my garden flowers. The machine would always crash onto a blue screen, what Joseph called the blue screen of death, and I would turn it off and then turn it on again and it would start-up properly, if still laboriously. Then I opened my inbox; I let the emails download for half-an-hour and returned to it to delete almost every one. Occasionally, there was a message from Joseph or the NHS or something, but most of it was for penis enlargers, Russian blondes and diet pills. And as I had no penis, had long lost interest in blondes—Georgian or otherwise—and could use more weight not less, all of it was for nought.

I had not touched the browser for over a year, having once been an obsessive addict of the online world, a hypochondriac and devourer of medical factoids, attempting to become a specialist in my own symptomatology. Charting every ache, every pain, offering my own prognoses, I competed with the pessimism of my doctors, conceiving worse and worse fates for myself. But eventually, after finding some gruesome pictures of my affliction untreated, I cured myself of my obsession and quit the web. But it was still there, my Mozilla Firefox—the delightfully named browser by which I entered this disembodied world. And there was a letter from Carol on the computer desk, one I had been reading all morning. It told me about Carol’s upbringing, how she moved from family to family at will, how she had met her best friend and sometimes lover Sayer Kilby Bailly.

I typed the name into Google; if more than one Carol Vaughan existed, why not another, but real-world, parallel for Mr. Sayer Kilby Bailly? Someone who, in that other world, had grown alongside my doppelgänger, but in this one had never met me. It demonstrates just how far gone I was to be thinking according to the logic of these letters, but I did not truly expect to find anything. And I definitely did not expect to find Dr. Sayer Kilby Bailly.

Not only did he exist, but also he had a website called Letters From Nowhere dedicated to the mysterious snail mail.

He wrote, ‘These letters are far too consistent and are received by people considerably too removed to be a set of unique delusions the similarities of which are explainable in terms of cultural tropes. Perhaps some semi-mystical mechanism such as the Jungian collective unconscious provides an explanation, but whatever the reason for them, I am utterly persuaded that the majority of people who receive letters from nowhere have no shared basis for their claims.

‘Nonetheless, they do share a common trait. If you have found this website because you are one of the recipients, be forewarned that you may wish to stop reading at this point. I do not wish to bring you any distress. What I am about to convey might be something you do not wish to read.

‘They all, without exception, die around three and a half years after receiving their first letter and about two months after they receive their last letter.’

I stopped reading.

My first letter had arrived just over two a half years ago. If Dr. Sayer Kilby Bailly was right, I had less than a year left. And reading those words took me back half a decade to the dull, sterile white office with its slatted curtains looking out to a concrete car park, and to the long faced, greying doctor who delivered my less definite but still wounding prognosis in a dulcet tone.

I learned a long time ago to take a practical approach to time. My body aches and if I stare into the middle distance hours vanish. At first this aspect of my illness was a locus of resentment; not only was the sickness shortening my life—fifty-four and I am like an invalid—but it was robbing even the lucidity I possess for the time I have remaining. My time was being stolen from every direction: my past taken in the form of memories, my present, in my inability to hold on to waking, active life and my future by my imminent mortality.

But to resent time is just too heavy a resentment. So, gradually, I took an easier approach, happy for every daily allotment of success—just getting out of bed, a shower—and unconcerned by the inevitable, and inevitably more common, failures. When it came to time, I held the lowest possible expectations.

It was a fortnight until I returned to Dr. Sayer Kilby Bailly’s website. But as I experienced that passage of moments, it could have been later the same day or after the elapsing of a whole year.

I wrote him an email outlining my situation.

He emailed back the same day, although I saw and read his email three days later:

Dear Ms. Carol Vaughan,

I hope this email finds you okay. I am so sorry to read of your illness and distress.

And I am sorry if my website in any way contributed to the latter. I have the utmost belief in your letters. Your approach of keeping them secret is not rare. So much so that I wonder how many recipients never convey the important missives delivered to them and how much knowledge of this other world is consequently lost.

Your scepticism is understandable, but I assure you that your letters are real. That the other Carol exists and, I strongly believe, communicates to you from benign intentions only.

Please, if I could visit you anywhere, at any time of your choosing, I would deeply appreciate a chance to talk in person. Especially since you are the first person I have met who claims that my name was mentioned in a letter. Perhaps one day this other Sayer will write to me too?

Yours sincerely,

Sayer

It was another four days before I decided to reply and a further three to fully draft and edit my response:

Dear Sayer,

Thank you for your email. As you know, I am not well, but I am prepared to accept a visit from you after my son and daughter-in-law have left from their weekly visit, at 1pm this next Sunday. Please, do not expect too much and be prepared for a very short visit.

I want to know more. Please find my details below.

Warm regards,

Carol

Small, elegant rituals still gave my life dignity. And one of my favourites—along with preparing espressos and sitting down to read—is using a letter opener. I used it on every letter from nowhere. And when Dr. Sayer Kilby Bailly’s first class letter arrived with the day’s letter from nowhere, I happily used it on that too—charmed that he had opted to reply offline. His letter was short:

Dear Carol,

I will arrive at the date and time given. I look forward to discussing your letters.

Yours sincerely,

Sayer

That Sunday my son’s visit dragged. My eye looked to the dark grandfather clock that ticked behind Samantha and my Joseph. As usual, Joseph was quiet, staring out of the dining room window into my garden where he had played on the lawn as a boy. He was looking at the sycamore tree still growing there. Samantha talked about her work at the accountancy, weather, documentaries she liked about history or geography, the local branch of the Liberal Democrat Party and redevelopment in the town centre. Neither one of them looked at or spoke to one another.

They left at 12.30 after Samantha cleaned up and I waited another forty-seven minutes before the doorbell rang. He smiled awkwardly as I let him in, and slouched a bit too much. It took him a while to get going, but when he did the initially taciturn impression he gave was completely dispelled.

‘One of those contacted, he received vivid descriptions of the cities,’ continued Dr. Sayer getting close to midnight that day.

He was a short, balding man whose rotund face was framed by a closely cut red beard and large, flappy ears. He had a shy grin that belied a manic comportment when he talked of matters relating to the letters. I loved his energy.

‘He did not save the writing, but was an illustrator for a major publisher. So he drew the descriptions out of his letters from nowhere. These are a rare glimpse of this other place. He gave them to me before he died; he said that nobody else would appreciate their significance. I present to you, Carol, the closest we have to photographs of this utopia.’

The beige portfolio he put down on the pale wood of my living room coffee table opened up and out spilled charcoal drawings of buildings. They were like the brutalist buildings of postwar London, except larger, more monolithic and even more ambitious in their elaborate shapes and sizes.

And there was a cleverer use of plants than I had ever seen in any real city. The monochromatic grey of the sketch at first disguised the verdant use of shrubbery, but soon I perceived that between the buildings was a thick veil of trees, and every window sported more florae so that it was as if the buildings were repositories for them rather than people. It was a city, but overgrown, a forested metropolis of strong slab monuments.

I wasn’t sure what to say as he smiled from the settee, but his use of the word utopia had irked me. ‘I don’t know if I would call it a utopia,’ I complained. ‘This other Carol is insufferable and sometimes even a little frenzied. She is always condescending, especially when writing about the history of her world and in her presumptions about ours, and about me; she is a snob. If such a person is a product of utopia, perhaps I am glad not to be.’

He just kept smiling. ‘I met a young man fifteen years ago, one of the first to get these letters as much as I can tell, and he told me the same thing; although, I didn’t call them utopian then. Now I’m convinced. Although they are not flawless angels, their world is a kind of paradise.’

‘Uh-huh,’ I murmured.

‘Here, look at this one,’ and he shuffled through the pile of pictures to one depicting a pathway through a forest, but with buildings rising up beyond the canopy. The artist had rendered dappled light and depicted a huge crowd of people in some kind of parade, in various costumes: great, flowing dresses adorned men and women, billowing back like ship sails; elaborate hats with points and orbs and more fluttering fabrics; people in close fitting garments with patchwork designs like troupes of harlequins; masques depicting great grotesques smiling and laughing and grimacing.

‘Carol always made me think of them as austere. I had in mind a society of intellectual idiots.’

‘If there is one thing I have learned in my time studying the letters from nowhere, it’s that utopia is a diverse place. It has an abundance of everything, a multitude of ethics and faiths and so many ways to live. Until you can interpolate more than one set of letters people always have the impression of a world taken to a single monomania. This artist believed it was a carnival utopia, a world in constant celebration. He believed that because that was his doppelgänger’s life. Your Carol is, perhaps, something like an academic, maybe a member of some society of readers or perhaps a hermit contented with her studies.’

‘There are hermits in utopia?’

‘Apparently. This world, this other world, permits so much more variation than ours. As far as I can tell, it reviles any attempt to impose a single template on life.’

I nodded and sipped my now cold tea. I was suspicious of all of this. I imagined coming to some vile dystopia and watching an agitprop film, like the ones doubtless made by the Nazis, describing the glorious accomplishments and perfect lives of the citizenry. I was also tired. My legs hurt and there was an uncomfortable, bloated feeling creeping from my belly to my chest, which made me irritated at having a guest present.

‘I… it was…’

‘Ah,’ he held up his wrist, checking a clunky watch, ‘I have overstayed.’

‘No, not at all.’

‘But I have. And I should be making my departure.’ He smiled, showing off some crooked but clean teeth. ‘Can I come back?’

‘I…’

‘You don’t have to answer right now.’

‘Yes, you can. Come the Sunday after next if you wish.’

Dr. Sayer Kilby Bailly is not the kind of man I would have been interested in during my youth. He was silly, excitable, a bit myopic. But weeks of enforced isolation made me happy for his attentions, even if he was mad.

When I told Samantha about him she was very interested, ‘I will Google stalk him for you,’ she said.

‘Stalk him?’

‘It’s normal and it’s only online, you know, to find out if people are okay. I always look them up to make sure they’re not part of a cult or something.’

I agreed, reluctantly.

The Saturday before he was due to visit the second time, Samantha came to me with a deluge of information. She took Bernard off his leash and watched as he huffed over to the couch to take a long afternoon nap, snoring loudly.

‘This Sayer guy part-owns an antique bookshop in London, Tomorrow’s Novel. I think he runs it with his brother. They inherited the business from their father and it’s famous. Been around for decades and in the same family. He has a few nieces and a dead nephew, but I don’t think he’s married. His Ph.D. is in biochemistry, but there’s no evidence he’s ever really used it. And he runs that website you mentioned. It seems kinda big. Like, there’s a Facebook group, a hashtag on twitter…’

‘A hashtag?’

‘It’s like a key word that you can use on the social network.’

‘Like Facebook?’

‘Yeah, kinda. Anyway, these letters from nowhere are all over. Hey, Carol, is that why you see him? Do you get these letters?’ She looked at me with her mouth clenched. She breathed in sharply.

‘Yes, but please don’t tell Joseph.’

Samantha laughed, but as though she hadn’t meant to laugh so that it was a little violent and quickly repressed. ‘Sorry, no… I mean, we don’t talk much. I love the world of your son, y’know? But…’

‘It’s okay,’ I interrupted.

As with his previous visit, Sayer was excited to talk about his favourite subject. He started, with little encouragement, by defining what makes a utopia a utopia. ‘I think J.C. Davis, Karl Mannheim and Krishan Kumar provide the best definitions,’ he said, as if I knew any of those people. ‘They don’t all agree, but we get a good idea by taking aspects of all three. First,’ he held up a stubby finger, ‘we need to distinguish, as Davis does, between a utopia and other ideal-worlds. For example, a utopia is not like the island of Cockaygne…’

‘The island of Cockaygne?’

‘Yes, it’s a medieval Irish mythical place where sailors occasionally wash up. It has shops that give everything away for free and rivers and houses and streets made of infinitely replenished food. Birds will fly out of the sky and land compliantly on your fire to roast themselves for your pleasure. There’s a more futuristic term for this kind of place, a post-scarcity society. A lot of modern science fictions use inexplicable technology to create the same result, but a utopia is not a world without limits. It’s the world, as it exists, populated by people as they are, but it’s better organised. The institutions are what is different.’

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘Next,’ Sayer held out two fingers, ‘we need to understand that utopia is not about perfection. It’s not perfect institutions, no more than any utopian author can expect to be able to devise such, but just better, according to someone. Mannheim gives us this part. And finally,’ he held up three fingers, smiling, ‘Kumar says that a literary utopia is always conveyed in a story. I think the letters from nowhere, therefore, count as utopian. In the literary sense, even if, perhaps, in some other way, they are not wholly fiction.’

‘I wonder why they communicate by letter,’ I mused out loud, hoping to break his flow a little.

‘It is not always just letters,’ he answered quickly. ‘Sometimes it is emails. Especially when it involves younger people. And for one person I met, it was phone calls. Everyday a phone call, by mobile.’

‘You mean, someone talked to one of these doppelgängers?’

‘No, it was a pre-recorded message. And the voice was robotic, like a computer reading out text. At least according to the women who received the calls, I never heard any just as I have never seen a letter from nowhere. Nobody, as far I have been able to discover, has ever talked back to nowhere. Utopia has somehow found a way to talk to us, but it has never been the other way around.’

Sayer reminded me of my other self’s way of talking, of the other Carol’s sometimes endearing pomposity. I always got the impression that he loved his own voice, was intoxicated by his own words. Not in a bad way, although he could be smug, but as if he was bewitched with wonderment for any subject on which his mind rested.

He would talk on tangents on and on, his voice merging with the ambiance of my home—the dulled whoosh of cars from outside, the chirping birds from the garden, the whirr of my fan during a suffocating summer day.

There would be a lull as we drank tea, sometimes I would even drift off. ‘As far as I can tell,’ he would start, apropos of nothing, looking up from a pile of papers, ‘they have something akin to a celebrity culture, but their celebrity culture is very niche. In fact, this quality of niche is what prevents them from being aristocratic, really. It’s what holds in check their social resentment, which the evenness of their distribution would otherwise leave out of control.

‘They have no household celebrities for the simple reason that they have no pervasive household culture at all. Instead, their society is a great, shifting, overlapping sea of parochialisms, adapting and altering too fast to be documented or understood holistically.

‘Certain people are famous to a subset of aesthetic devotees, which will change depending on the given artist’s—and they are all artists, in some sense—style of the moment. And every artist will in turn be a devotee. It is a utopia of writer’s writers, painter’s painters, architect’s architects.’ In this way he would continue and could do so, uninterrupted, for as many as five or six hours before becoming flustered, apologising, asking if I still wanted him to visit, and arranging to come by the next week or—if I felt very tired—the week after that.

Waiting for Sayer’s visits had a peculiar benefit. It slowed down time. He was sometimes insufferable, but always entertaining, and because I wanted his company I felt the weight of time between each new encounter. Sayer had restored something to me, however accidentally, and I felt the same kind of gratitude to him as I had previously felt only to Samantha.

I wondered a lot about Samantha and her devotions to her husband’s mother, despite her failing marriage. What obligation compelled her? I would have tried to free her of it all: myself, my son. Nobody should waste away in a loveless marriage. But I was too scared by the material implications. I selfishly wanted to keep her. And not only as a visitor, but even just as a dog walker. Seeing them—the loveless couple—sitting with each other every Sunday morning would make me horrendously guilty, the kind of guilt you feel physically, a nausea.