13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

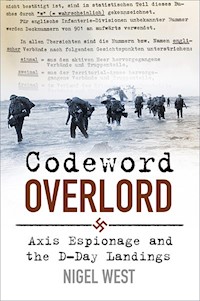

It was inevitable that the Allies would invade France in the summer of 1944: the Nazis just had to figure out where and when. This job fell to the Abwehr and several other German intelligence services. Between them they put over 30,000 personnel to work studying British and American signals traffic, and achieved considerable success in intercepting and decrypting enemy messages. They also sent agents to England – but they weren't to know that none of them would be successful. Until now, the Nazi intelligence community has been disparaged by historians as incompetent and corrupt, but newly released declassified documents suggest this wasn't the case – and that they had a highly sophisticated system that concentrated on the threat of an Allied invasion. Written by acclaimed espionage historian Nigel West, Codeword Overlord is a vital reassessment of Axis behaviour in one of the most dramatic episodes of the twentieth century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Cover illustrations: Front: Beach Group troops wade ashore from landing craft on Queen beach, Sword area, on the evening of 6 June 1944. (IWM) Back: Landing ships putting cargo ashore on one of the invasion beaches, at low tide during the first days of the operation, June 1944. (US Coast Guard Collection/US National Archives)

First published 2019

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Nigel West, 2019, 2022

The right of Nigel West to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 176 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The military organisation that has the most efficient reconnaissance unit will win the next war.

General Werner von Frisch, 1938

The invasion does not yet appear to be imminent.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, C-in-C West, 5 June 1944

During the night and the early hours of this morning the first of the series of landings in force upon the European Continent has taken place.

Winston Churchill, House of Commons, 6 June 1944

A considerable degree of surprise was achieved throughout.

Brigadier Edgar Williams, 21st Army Group, 6 June 1944

The Allies scored a great surprise on 6 June 1944 by the imposition of radio silence.

General Albert Praun, OKW Chief Signal Officer

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements and Author’s Note

Glossary and Abbreviations

Introduction

Dramatis Personae

1 OVERLORD

2 German SIGINT

3 Luftwaffe Aerial Reconnaissance

4 Protecting OVERLORD

5 The Iberian Front Line

6 BODYGUARD Spies

7 The Intelligence Assessment

8 The Rommel Analysis

9 MUSGRAVE

10 Phase II

11 Stay-Behind

Postscript

Appendix I Führer Directive No. 51, Dated 3 November 1943

Appendix II Baron Oshima’s Inspection of the Atlantic Wall, October 1943

Appendix III FUSAG Components

Notes

Select Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND AUTHOR’S NOTE

The author acknowledges his debt of gratitude to those who have assisted his research, among them the late Bill Williams, Roger Hesketh, David Strangeways, Noel Wild, Juan Pujol (GARBO), Roman Garby-Czerniawski (BRUTUS), Harry Williamson (TATE); Frano de Bona (FREAK); Ib Riis (COBWEB) Dusan Popov (TRICYCLE); Elvira de la Fuentes (BRONX), Lisel Gärtner, Hugh Astor, Christopher and Pam Harmer, Cyril Mills, Desmond Bristow, Tommy and Joan Robertson, Russell Lee, Bill Luke, Philip Johns, Cecil Gledhill, Kenneth Benton, John Codrington, Brian Stonehouse, Tony Brooks, Ladislas Farago, Gunter Peis, David Kahn, Jack Beevor, Anthony Coombe-Tennant, Vera Atkins, Rob Hesketh and Bill Cavendish-Bentinck. Also Marco Popov, Jennifer Scherr and Christopher Risso-Gill.

Many of the documents reproduced in this volume originate from official files and have been redacted during the declassification process. Where possible the redactions have been restored, but where this has not been possible the redaction is indicated thus: [XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX]

The author has retained the convention of printing code names in capitals but, for ease of reading, has restored capitalised surnames to ordinary, lower case.

GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS

AA

Anti-Aircraft

Abt

Abteilung

AFU

Agentfunkgerät

Amt

Office

APO

US Army Post Office

Army Group B

Commanded by Erwin Rommel

B-Dienst

Beobachtungdienst

B1(a)

MI5 section handling double agents

B1(g)

MI5’s Spanish section

BCRA

Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action

BEF

British Expeditionary Force

BJ

BLACK JUMBO diplomatic decrypt

CENTRO

KO Madrid’s wireless station

COMZ

Communications Zone

COSSAC

Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander

CSDIC

Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre

CW

Continuous Wave

DB

Director, B Division MI5

DGS

Dirección General de Seguridad

DOWAGER

Ops (B) in Italy

DSO

Defence Security Officer

FA

Reichsluftfahrtministerium Forschungsamt (Foreign Ministry Research Office)

FAK

Nachrichten Fernaufklaerungs Kompanie (Long-range intercept company)

Feste

Feste Nachrichten Aufklärungsstelle (stationary intercept company)

FHW

Fremde Heere West

Fnu

First Name Unknown

FSS

Field Security Section

FU III

Funkabwehr

FUSAG

First United States Army Group

GC&CS

Government Code & Cipher School

GIS

German Intelligence Service

GPO

General Post Office

GRT

Gross Registered Tonnage

GSP

Gibraltar Security Police

H Gp B

Heere Group B

Hoeh Kdr D Na

Hoeherer Kommandeur der Nachrichten Aufklaerung (Senior Communications Intelligence Officer)

I-H

Eins Heer

I-L

Eins Luft

I-M

Eins Marine

ISOS

Abwehr decrypts

JIC

Joint Intelligence Committee

JMA

Japanese military attaché decrypts

KO

Kriegsorganisation

KONA

Kommandeur der Nachrichtenaufklärung

LCI

Landing Craft Infantry

LCP

Landing Craft Personnel

LCS

London Controlling Section

LCT

Landing Craft Tank

LN Rgt

Luftnachrichten Regiment

MI 14

German order of battle section in the War Office

MI5

British Security Service

MI6

British Secret Intelligence Service

MoI

Ministry of Information

MP

US Army Military Police

MSS

Most Secret Sources

NKVD

Soviet intelligence service

OB West

Oberbefehlshaber West

OKH/Chi

Oberkommando des Heeres, Chiffrierabteilung

OKH/GdNA

Oberkommando des Heeres, General der Nachrichten Aufklaerting

OKL/LN

Luftnachrichten

OKM/SKL III

Seekriegsleitung III

OKW

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

OKW/Chi

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Chiffrierabteilung

OSS

Office of Strategic Services

PCO

Passport Control Officer

Pers Z Chi

Personal Z Chiffrierdienst des Auswärtigen Amtes

Pers Z S

Personal Z Sonderdienst des Auswärtigen Amtes

PF

Personal File

PR

Photographic Reconnaissance

PVDE

Polícia de Vigilância e de Defesa do Estado

PWE

Political Warfare Executive

RSHA

Reich Security Agency

RSS

Radio Security Service

SD

Sicherheitsdienst

SIA

Servizio Informazioni Aeronautica

SIGINT

Signals Intelligence

SIM

Servicio de Información Militar

SIPO

Sicherheitspolizei

SIS

British Secret Intelligence Service

SIS

Italian Speciali Servizio Informazioni

Skl

Seekriegsleitung

SOE

Special Operations Executive

SOS

US Army Services of Supply

V-Mann

Verbindungsmann

WOC

War Office Cipher

X-2

Counter-intelligence branch, OSS

XX

Twenty Committee

Y

Wireless interception

INTRODUCTION

Seventy-five years ago, on 6 June 1944, 168,000 Allied troops stormed ashore on the beaches of Normandy to begin the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe, supported by 12,000 aircraft and nearly 7,000 ships. The invasion plan, initially code-named OVERLORD and then designated NEPTUNE and a dozen other subordinate components, was the largest amphibious assault ever contemplated, and was an extraordinarily high-risk enterprise.

The daunting requirement to deliver a large number of heavily armed soldiers, and their supporting weaponry, to a well-defended coastline imposed significant challenges. The key to success would be the element of surprise, but the enemy was fully aware that an invasion attempt was probable sometime during the summer of 1944. The only issues at stake were the precise timing, and the exact location. If the ultimate Allied objective was to cross the Rhine, occupy the industrial assets of the Ruhr and reach Berlin, the most direct route seemed obvious.

Conventional military doctrine dictated that the invading forces should be at sea for a minimum period, so as to avoid a major naval engagement in which the convoys of troopships would be bound to suffer heavy losses. The less time the troops were afloat, the smaller the chance of a U-boat attack, of convoys blundering into a minefield, or of discovery by an E-boat patrol, maritime picket or by aerial reconnaissance. These and similar considerations dictated that the most propitious route would be across the shortest distance, the 23 miles from the Kent ports to the Pas-de-Calais. As regards timing, the tides, moon and weather would be crucial.

Such a plan enjoyed many merits, including the opportunity to provide maximum air cover over the combat zone, with Allied aircraft requiring only the minimum time to return to base to refuel and rearm. Considering that a fully equipped Spitfire only carried enough ammunition to fire its .303 Browning machine guns for less than twenty seconds, this factor was likely to be mission-critical, especially as ground support and air superiority would be absolutely vital in seizing and holding any beachhead.

Another significant necessity was the logistical resupply, involving armour, food, fuel, ammunition and transport. Past experience of beach landings had demonstrated the need to capture a medium-sized, deep-water port, with its handling facilities intact. This was a tall order, but the Calais region boasted several such towns, including Dunkirk and Boulogne, and opened up the possibility of cargo ships sailing directly from the United States.

Finally, there was a political dimension that would influence German thinking, but was unknown to the Allies. Adolf Hitler had often spoken publicly about his intention to unveil innovative new secret weapons that had a war-winning potential, and had intended a V-1 offensive for October 1943, but his scheme went awry through the intervention of Allied bombers that delayed Volkswagen’s production of the doodlebug missiles that were to be deployed in northern France in a ruthless terror campaign to flatten London. Thousands of these pulsejet-powered weapons were to be catapulted against the city from the middle of June 1944, at a rate of seventy-two per day from 104 ramps, and the German High Command (OKW) anticipated that the scale of the air offensive would force the British War Cabinet to make the elimination of the launch sites an overriding strategic priority. Indeed, Hitler predicted at a staff conference that his secret weapons would generate enough political pressure to force Churchill from office.

The Germans knew that there was very little to be done to prevent that V-1 from reaching the capital, and that there was absolutely no defence against the V-2 ballistic missile. By the end of the war the British Civil Defence authorities had logged 5,823 flying bomb incidents, of which 2,242 landed on London, killing 6,184 civilians and 3,917 members of the armed services. A further 17,981 civilians and 1,939 servicemen were injured, and 23,000 homes destroyed.

Hitler understood the strategic implications of allowing a beachhead to be gained, and on 3 November 1943 he had issued Führer Directive 51 (see Appendix I) to prepare for what he saw as the coming Allied offensive. However, Field Marshal Rommel’s preferred solution was a swift armoured counter-attack mounted by some of the ten Panzer divisions already garrisoned in France.

The Allies’ masterplan was devilishly complex, involving the embarkation of troops at eleven different south coast ports, from Falmouth in the west to Newhaven in the east, destined for the five designated beaches in Normandy. In recognition of what might go awry, they deployed fifteen hospital ships, staffed by 10,000 doctors, and prepared 124,000 beds for potential casualties.

When weighed objectively, taking into account all the relevant military and political considerations, it seemed obvious that if the Allies were to have the slightest chance of overwhelming Rommel’s so-called impregnable Atlantic Wall, manned by fifty-eight divisions of the 7th and 15th Armies, they would have to assemble in south-east England and rush across the Channel to Calais during the full moon, at high tide, perhaps relying on a diversionary attack elsewhere to draw the defenders in the wrong direction.

Of course, we now know that the focus of D-Day was in Normandy, and that in the absence of any available ports the Allies constructed two huge MULBERRY harbours off the beach where the pontoons were protected by sunken block-ships acting as breakwaters. Innovative engineers also designed and installed an underwater fuel pipeline code-named PLUTO (‘pipeline under the ocean’), laid on the seafloor from Niton in the Isle of Wight, to sustain the invasion vehicles, thus reducing the need for vulnerable tankers to make the long voyage from Plymouth or Southampton in seas likely to be infested by an estimated 125 U-boats1.

For many years much secrecy surrounded the concept of strategic deception, but a series of disclosures in the 1970s revealed that a group of ingenious American and British planners had persuaded the Allied Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, that a gamble on Normandy in preference to the more obvious choice, might catch the enemy off guard and enable a sizeable beachhead to be achieved before encountering the danger of counter-attack. The argument was that the OKW was predisposed to accept the Pas-de-Calais as the only sensible invasion objective, and the Allies possessed the means to reinforce this judgment by providing the necessary evidence. Indeed, the deception planners exercised control over the enemy’s network of spies, had access to his most confidential communications, enjoyed air superiority and could impose the very strictest security conditions on the British Isles that could not be matched anywhere on the Continent with its porous land frontiers. These factors combined to create a unique set of circumstances that could be exploited by an intelligence community which had experimented with deception schemes in the Mediterranean and Middle East to gain unprecedented experience of the art of misdirecting the Axis. The results achieved in those theatres suggested that skilful, co-ordinated manipulation of wireless traffic, double agents and camouflage could accomplish much by exaggerating strengths, disguising weaknesses and confusing the adversary.

The gamble, concealed by the codeword BODYGUARD, was momentous in every respect. Experience gained at Dunkirk, Dieppe, North Africa, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, Attu and Kwajalein showed that Allied troops were at their most susceptible when they made their way ashore in slow, poorly protected landing craft, to then negotiate the beach obstacles and evade the lethal crossfire from heavily fortified installations manned by seasoned veterans of the Russian front. The implications of a major defeat on the Cherbourg peninsula, with the invaders pushed back into the sea, would be dire, and certainly delay any further attempt for another year. Following his victory, Hitler would be free to move reinforcements to the east, and he would also have the benefit of the V-1 and V-2 onslaught. Perhaps, with his stock high, the Wehrmacht would not have been motivated to attempt a coup on 20 July, and he might have bought sufficient time, maybe an extra two years, to develop jet fighters and invest in an atomic bomb. This is sheer speculation, but such conjecture gives some context to what was riding on the chance to free Europe from Nazi tyranny.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

José Aladren

Spanish journalist and FBI double agent code-named ASPIRIN

ALMURA

GARBO’s (notional) radio operator in London

Helmut Arntz

Adjutant to General Praun

Brian Atkinson

DSO Malta

Fritz Bayerlein

Commander, Panzer Lehr Division

Elyesa Bazna

Code-named CICERO; valet to the British ambassador in Ankara

Herbert J. Bechtold

Abwehr NCO in Paris, code-named JIGGER

BEN

(Notional) Greek deserter seaman living in Methil

Kenneth Benton

SIS Section V officer in Madrid

BERTIN

Unidentified Abwehr stay-behind agent

John Bevan

Head of the London Controlling Section

Wolfgang Blaum

Alias Friedrich Baumann, head of Abt. II in Madrid until February 1945

Frano de Bona

TRICYCLE’s radio operator, code-named FREAK by MI5, accredited as the Yugoslav military attaché

Juan Brandes

Suspected Abwehr fabricator in Lisbon

Augusto Calvo

Son of WITCH, younger brother of COCK, Abt. II saboteur and member of the CRAZY GANG

Carlos Calvo

BRIE, older son of WITCH. Former Spanish army officer, Abt. II saboteur and deputy head of the CRAZY GANG

Joachim Canaris

I-H officer in Madrid KO

Wilhelm Canaris

Chief of the Abwehr until February 1944

Francisco Cano

Spanish saboteur identified by JOE. Cano denounced Gonzalez and Mateos

Alberto Carbe

Abwehr II officer at the Villa Leon, Algeciras

CASTOR

US Army sergeant and GARBO’s unconscious source

Bill Cavendish-Bentinck

Chairman, Joint Intelligence Committee

CHARLES

Abwehr agent Jean Senouque in Cherbourg

CHOPIN

BRUTUS’s (notional) wireless operator

Antonia Choxas

Code-name WITCH, double agent in Gibraltar, mother of the Calvo brothers

Ramon Correa

A double agent employed as a dockyard labourer, Falange saboteur COCK who sank the Erin in January 1942 with Fermin Mateos, elder brother of BULL. PEG’s deputy and suspected triple agent

Ernesto Cozas

(Notional) saboteur invented by Alfonso Olmo and impersonated by OGG

Fritz Cramer

Abwehr IIIF in Lisbon

Hans Cramer

Afrika Korps general and repatriated PoW

CRAZY GANG

Spanish saboteurs working for Abt. II, headed by Plazas and BRIE

Luis Cordón Cuenca

Spanish saboteur arrested in Gibraltar in August 1943

DICK

GARBO’s (notional) sub-agent 7(4), and Indian nationalist in Brighton

Juan Dodero

Suspected Falange saboteur excluded from Gibraltar after he was denounced by COCK. He died in 1944

Alfredo Dominguez

Falange saboteur and Gibraltar dockyard labourer

DONNY

GARBO’s sub-agent 7(2) in Dover, named David

DORICK

GARBO’s sub-agent 7(7) in Harwich

Carl Eitel

Abwehr officer in Lisbon code-named SPEARHEAD

Edward Ejsymont

A Polish Air Force cadet code-named CARELESS by the British and KORAP by the Germans

F.1

Double agent in Gibraltar, brother of F.2

F.2

Double agent in Gibraltar, brother of F.1

FRANCISCO

German Abt II officer in Madrid in 1942

FROG

Unemployed Spaniard in La Linea recruited as a saboteur by COCK. An occasional fruit vendor, elder brother of BULL and member of the CRAZY GANG

FRUITIES

Double agent network consisting of F, F.1 and F.2

Paul Fidrmuc

Abwehr source code-named OSTRO

Frank Foley

SIS officer

Jean Frutos

Double agent in Cherbourg code-named DRAGOMAN by the British and EIKEL by the Germans

Alfred Gabas

French naval officer and double agent in Cherbourg code-named DESIRE

Roman Garby-Czerniawski

Abwehr V-Mann 372. Code-named BRUTUS by MI5

Friedle Gärtner

Abwehr agent code-named GELATINE by MI5

Walter Gaul

Kriegsmarine liaison officer attached to the Luftwaffe

Alfred Gensorowsky

Head of Abwehr III in San Sebastian

William Gerbers

GARBO’s (notional) Agent 2, died on 19 November 1942 in Bootle

Angel Gauceda Sarasota

A double agent recruited for the Germans by BRIE. A Basque, employed as a lorry-driver in the Gibraltar dockyard, code-named CARELESS by the British and NAG by the Germans

GON

A chemist working as a British double agent in Gibraltar

Paciano Gonzalez

Spanish saboteur denounced by Cano. Former army officer arrested in Spain in July 1944

Anthony Gordon-Bright

Head of the MoI’s Spanish Section, code-named AMEROS, GARBO’s (notional) unconscious sub-agent

Hermann Göritz

Head of Abwehr Barcelona 1944–45

Willi Hamburger

Abwehr defector in Turkey

Leonard Hamilton Stokes

SIS station commander in Madrid

Tomás Harris

Head of MI5’s B1(g)

Roger Hesketh

Ops (B) deception planner

Jack Ivens

SIS Section V officer in Madrid

Ralph Jarvis

SIS station commander in Lisbon

Johann Jebsen

Abwehr officer code-named ARTIST by SIS

JOE

Double agent in Gibraltar

Otto Kamler

Abt. I officer in Madrid, then Lisbon, alias of Otto Kurrer

Cornelia Kapp

SD defector in Ankara

KEEL

SD double agent in France

Rudolph Kellerman

Head of Abwehr Barcelona 1943–44

José Estella Key

Codenamed RATS by MI5

Philip Kirby Green

Deputy Defence Security Officer, Gibraltar

Friedrich Knappe-Ratey

Abt. I officer in Madrid, code-named FEDERICO

Bertie Koepke

I-H officer in Barcelona

Rolf Kolding

Head of Abwehr Barcelona 1942–43

Walter Kopp

Signals Chief, OB West

KORAP

Abwehr code name for Edward Ejsymont

Ludwig Kramer von Auenrode

Chief of Madrid KO, alias von Karstoff, code-named LUDOVICO

Friedrich-Adolf Krummacher

OKW intelligence chief

L

Elderly Spanish fisherman and DSO informant arrested in La Linea in March 1944

George Lang

Abt I officer in Madrid, code-named EMILIO

Adolf Langenheim

German consul in Tetuan

André Latham

Abwehr agent, code-named GILBERT

Johnny Leden

Notional USAAF mechanic, run by JEEP

Renato Levi

Code-named CHEESE by MI5; ROBERTO and V-Mann 7501 by the Abwehr

Guy Liddell

Director, MI5’s B Division

Peter Lloyd

SIS Section V officer

LOTHAR

Unidentified Abwehr stay-behind agent

Maria Marek

Croat code-named THE SNARK by MI5

John Marriott

MI5 officer

José Martin Muñoz

Spanish saboteur arrested in Gibraltar in August 1943 having been identified by NAG, code-named PITUS

J.C. Masterman

Chairman, XX Committee

Fermin Mateos

Spanish dockyard labourer and saboteur denounced by Dodero and by Cano, and excluded from Gibraltar. He sank the Erie with Ramon Correa

H.G. (‘Tito’) Medlam

DSO, Gibraltar

Alfred Meiler

Alias Alfred Kohler, code-named PAT J by the FBI

Wolfgang Menem

Abwehr II contact of SUNDAE

Cyril Mills

MI5’s liaison officer in Canada

MIRA

Abwehr code name for Fermin Mateos

General Frederick Morgan

Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander

Brian Morrison

SIS Gibraltar

Ludwig Moyzisch

SD representative in Ankara

OGG

Spanish double agent in La Linea, employed in the dockyard as an electrician, who posed as Ernesto Cozas

Alfonso Olmo

Bus driver and Spanish saboteur excluded from Gibraltar in October 1942

Osamu Otani

Japanese military attaché in Berlin

Aelred O’Shagar

SIS Section V officer, Gibraltar

Manoel Marques Pacheco

Portuguese Abt. I agent based in Tangier and then La Linea

Franz von Papen

German ambassador in Ankara

Marcelino Pardo

Spanish Falangist in Seville

Miguel Parra

Falange saboteur

PAT

Saboteur trained by Baumann in Seville in 1942

Gottfried Paul-Taboschat

Head of Nest Barcelona, code-named PABLO

PAULUS

Abwehr code name for Paciano Gonzalez

Kim Philby

SIS Section V officer

Emilio Plazas

Head of a Falange sabotage organisation directed against Gibraltar, code-named PEG

Manuel Pontalia Carrasco

Spanish saboteur excluded from Gibraltar

Dusan Popov

Code-named TRICYCLE by MI5, IVAN by the Abwehr and SCOUT by SIS

Ivo Popov

Code-named DREADNOUGHT by MI5

Albert Praun

OKW’s Chief Signals Officer

PRIMO

Italian double agent in Naples

Juan Pujol

V-Mann 319, code-named GARBO by MI5; IMMORTAL and BOVRIL by SIS; ALARIC by the Abwehr

QUEEN OF HEARTS

Polish double agent in Gibraltar who penetrated the CRAZY GANG. She recruited Carlos Calvo and NAG for the Germans and was married to Manuel Romero

Calixto Rodriguez

Alias Don Carlos Lunez, head of German sabotage organisation, code-named READY

Sir Edward Reed

MI5 officer

Edward de Renzy-Martin

SIS station commander in Madrid

Ib Riis

MI5 double agent in Iceland code-named COBWEB

T.A. Robertson

Head of MI5’s B1(a) section

Alexis von Roenne

FHW analyst

Manuel Romero

German agent run by Carlos Calvo. Husband of QUEEN OF HEARTS; harbourmaster at Puente Mayorga

Erwin Rommel

Commander, Army Group B

Colonel Sanchez Rubio

Spanish military intelligence officer code-named BURMA, also working for Abwehr II, paymaster for PEG in Algeciras

Gerd von Rundstedt

Commander-in-Chief, Armies West

Hans Ruser

Abwehr defector code-named JUNIOR by SIS

Charles de Salis

SIS Section V officer in Lisbon

Andres Santos

Suspected saboteur

SAP

British agent in the Gibraltar dockyard

Theodor Schade

Head of I-TLw at Madrid

Walter Schellenberg

Head of the SD’s Amt VI

David Scherr

Assistant DSO, Gibraltar

Percy Schramm

OB West’s War Diarist and official historian

SCHOOLMASTER

SIS agent in La Linea

Werner Schulz

Head of Abt. I in Madrid from February 1945

Enrique Schumer

Abwehr II contact of SUNDAE

Jean Senouque

Abwehr agent code-named CHARLES and SKULL

Natalie Sergueiev

Code-named TRAMP by the Abwehr and TREASURE by MI5

Manoel Serna

Member of the PAL sabotage network arrested in Gibraltar in June 1943

SKULL

Jean Senouque, French double agent

José Solis

Falange saboteur

Eugn Sostaric

Code-named METEOR by MI5

Hans Speidel

Rommel’s Chief-of-Staff

David Strangeways

SHAEF Ops (B) deception planner

STEM

Double agent in Gibraltar and elder brother of Fermin Mateos

STUFF

Agent inside the Plazas sabotage network

SUNDAE

Lieutenant Juan José Dominguez, double agent in Gibraltar, executed in Spain in September 1942

T-8

Spanish pilot and agent in Gibraltar

T-19

Spanish barman in La Linea and penetration of the CRAZY GANG

T-20

Clerk in Gibraltar’s Manpower Office

T-24

Spanish agent close to Colonel Sanchez Rubio

T-31

Spanish Communist, ex-Republican Army officer and Q.1’s nephew. Arrested in Spain in March 1944

T-45

Communist Spanish waiter at the Café Anglo in La Linea

T-48

Spanish secret police agent in La Linea

T-52

SIS agent, cousin of SCHOOLMASTER. Secretary in the DGS office in La Linea

T-63

Clerk in Gibraltar’s Manpower Office

T-66

Agent in the Malaga Secret Police, formerly in La Linea

Dorothy Thompson

GARBO’s (notional) mistress, code-named AMY, a secretary in the Cabinet Office

David Thomson

Assistant DSO Gibraltar

Peter Tomsen

Double agent in Iceland code-named BEETLE

TREE

Member of the PEG organisation

U.10

Spanish Communist refugee in Gibraltar and double agent

General José Ungría

Former SIM chief working for Abwehr II

Erich Vermehren

Abwehr defector in Istanbul, code-named PRECIOUS

Josef Waber

Abwehr II officer based in Madrid code-named JOSE

Noel Wild

SHAEF Ops (B) deception planner

Bill Williams

Chief Intelligence Officer, 21st Army Group

Harry Williamson

Code-named TATE by MI5; V-Mann 3725 by the Abwehr

Ian Wilson

MI5 B1(a) case officer

Francisco Zimmermann

German schoolmaster in Cartagena

1

OVERLORD

‘The whole project was majestic.’

Winston Churchill, Closing the Ring.

German Intelligence, in the form of Amt VI, the foreign intelligence branch of the Sicherheitsdienst, first learned of the code name OVERLORD when Elyesa Bazna, valet of the hapless British ambassador in Ankara, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, photographed the content of his employer’s document box and sold the resulting rolls of film to the local SD representative, Ludwig Moyzisch, on several occasions between 26 October 1943 and late February 1944. The source was considered so sensitive that Moyzisch handled CICERO (Bazna) personally, and did not initially consult his immediate superior, Paul Leverkühn, who was based in Istanbul.1

A post-war investigation into this appalling breach of security, based on interviews with an Amt VI interpreter, Maria Molkenteller2 and an Amt VI officer, SS-Obersturmführer Otto-Ernst Schuddekopf, revealed that the ambassador’s residence did not possess a safe, so Sir Hughe had stored his secret papers in a locked black tin box in his bedroom, but had left the key lying around so at least three members of his personal staff had access to it. Worse, the ambassador had persisted in this behaviour long after he had been warned about it in 1942. The first clue to the existence of a spy code-named CICERO, linked to Moyzisch, designated ‘6981’ appeared in the Prague–Istanbul ISOS channel dated 29 November 1943:

From 6981. Extracts from CICERO material on China can be passed on to 8027 if origin is in no way apparent. 8027.

According to Molkenteller, who had translated the CICERO product at the SD headquarters in Berlin, and was interrogated in London in 1945, it included between 130 and 150 secret Foreign Office telegrams.3 Dr Schüddekopf, a distinguished historian, confirmed that the SD was entirely satisfied by the documents’ authenticity, even though Moyzisch never identified Bazna’s woman accomplice.

The telegram, No. 1751 addressed to the ambassador, was in part a copy of a Chiefs of Staff policy document sent to General Eisenhower that mentioned a British intention ‘to maintain a threat to the Germans from the eastern Mediterranean until OVERLORD is launched’.

OPERATION ‘OVERLORD’

(a) This operation will be the primary United States-British ground and air effort against the Axis in Europe. (Target date, May 1, 1944.) After securing adequate Channel ports, exploitation will be directed towards securing areas that will facilitate both ground and air operations against the enemy. Following the establishment of strong Allied forces in France, operations designed to strike at the heart of Germany and to destroy her military forces will be undertaken. (b) Balanced ground and air force to be built up for OVERLORD and there will be continuous planning for and maintenance of those forces available in the United Kingdom in readiness to take advantage of any situation permitting an opportunistic cross-Channel move into France. (c) As between Operation OVERLORD and operations in the Mediterranean, where there is a shortage of resources available, resources will be distributed and employed with the main object of ensuring the success of OVERLORD. Operations in the Mediterranean theatre will be carried out with the forces allotted at TRIDENT, except in so far as these may be varied by decision of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. We have approved the outline plan of General Morgan for Operation OVERLORD, and have authorised him to proceed with the detailed planning and with full preparations.

When the German ambassador to Turkey, Franz von Papen, read this item on 6 January 1944, he immediately interpreted it to mean that OVERLORD represented a major action to be launched from Britain. His principal mission was to either maintain Turkey’s neutrality, or to persuade the government to join the Axis, so he was keenly interested in CICERO’s material, and was easily persuaded of its authenticity.

Evidently Hitler’s chief of operations, General Alfred Jodl, had reached the same conclusion. Von Papen, a professional diplomat who had engaged in espionage from the German embassy in Washington, D.C. during the First World War, also opined that the compromised text implied a classic diversion, that a British threat to the Balkans was intended to draw attention, and doubtless the enemy’s military assets too, into the region, while some other major initiative was launched elsewhere. While this verdict may not have disclosed any exact dates or targets, it did tip off the Axis to the existence of a very specific code word.

Bazna resigned his post at the end of February 1944, having taken fright at the unexpected appearance of security investigators at the chancery and residence, and cut his ties to Moyzisch after a final rendezvous in April, but the damage had been done. At his office in Berlin’s Birknerstrasse the Amt VI chief, Walter Schellenberg,4 also grasped the significance of OVERLORD. He issued a circular to all SD staff seeking details of any other references to the code word, and imposed a special search for additional references, particularly in any decrypts of Allied communications.

Born in Saarbrücken in 1910, Schellenberg had qualified as a lawyer and joined the Nazi Party in 1933. Two years later he was recruited into the SD and in November 1939 was entrusted by his chief, Reinhard Heydrich, with a delicate assignment, the abduction of two British intelligence officers at the Venlo border crossing into Holland, a highly successful mission for which he received the Iron Cross (first class) and promotion to Amt IV and counter-intelligence operations conducted with Abwehr III. He would also liaise closely, and develop personal friendships, with his Swiss counterpart, Roger Masson; the chief of the Turkish intelligence service, Mehmet Naci Perkel; and the head of the Swedish Security Police, Martin Lundquist. Suave, sophisticated and cosmopolitan, Schellenberg was the consummate counter-intelligence professional and he would play one of the key roles in the OVERLORD saga.

On 12 February 1944 Hitler signed an order to create a unified intelligence organisation, the Reich Security Agency (RSHA) headed by Ernst Kaltenbrunner, under the direction of Heinrich Himmler, which would absorb the Abwehr. The catalyst for this radical reform was the recent defection to the British of Erich and Elizabeth Vermehren in Istanbul, and the recruitment by the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Ankara of Moyzisch’s young secretary, Cornelia Kapp. The daughter of Karl Kapp, the German consul-general in Sofia, Nellie Kapp had been educated in Bombay and Cleveland, Ohio, and was an anti-Nazi. According to an SIS report addressed to MI5’s Alex Kellar dated 29 May 1944, Moyzisch had survived the defection (although his superior Leverkühn had not) because of support from von Papen, for whom he had worked in Vienna, and because Nellie had been certified ‘mentally deficient’.5

Both defectors had possessed valuable information and the damage they inflicted would be exacerbated by three further Abwehr defections, those of Willi Hamburger and Karl and Stella Kleczkowski. One of the first casualties of the Turkish debacle was the Abwehr’s chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, who was dismissed at the end of January, and then in early August arrested at his home at Zehlendorf in the Betazielestrasse by Schellenberg, who escorted him to an extended period of house arrest at the SIPO training school at Furstenberg in Mecklenburg.

These events were discussed at a conference called by General August Winter at ZEPPELIN, the staff headquarters at Zossen, which established a new section, designated Mil Amt, which would be responsible for the collection of military intelligence, with a particular requirement to provide advance warning of future enemy landings. This decision was endorsed by the Abwehr attendees, consisting of Admiral Leopold Burkner, Georg Hansen and Baron Wessel Freytag-Loringhoven of Abt. II; Franz von Bentivegni of Abt. III; and Colonel Heinrich, and effectively left responsibility for the collection of all military intelligence in the hands of the Abwehr’s Abteilung I. It was also agreed that Mil Amt, with a headquarters at Waldberg, near Furstenwalde, would be headed jointly by Hansen and Schellenberg, who would deputise for each other. When the ambitious Kaltenbrunner objected to this arrangement he was overruled by Himmler who had been persuaded by his friend and protégé Schellenberg that the SD had no experience of military matters, whereas the Abwehr had developed an expertise in the field. In practical terms the impact of this new structure was minimal, and the Kriegsorganisationen (KO) in Lisbon and Madrid were largely unaffected. Thus, although ostensibly the Abwehr had been absorbed into the Reich Security Agency (RSHA), much the same personnel continued their work in the collection of military intelligence. There would be more radical changes within the German intelligence monolith after D-Day, but during the vital period prior to the Allied landings, the individuals responsible for the recruitment and management of agents, and the assessment of information, remained mainly unchanged.

The extent to which the German analysts grasped the significance of the code word OVERLORD is not open to doubt, because on 8 February 1944 FHW issued an assessment on the subject:

For 1944 an operation is planned outside the Mediterranean that will seek to force a decision and therefore will be carried out with all available forces. This operation is probably being prepared under the codename of OVERLORD.

2

GERMAN SIGINT

‘The war will be won or lost on the beaches.’

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

31 December 1943

In the last months of the war a group of specially indoctrinated American and British intelligence officers was deployed in Europe, usually behind enemy lines in TICOM teams, to capture cryptographic equipment and archives, and to interrogate prisoners of war who were suspected of possessing a knowledge of German code-breaking.

The very existence of the Target Intelligence Committee was a closely guarded secret until details were declassified in 2010. TICOM personnel snatched large quantities of documents and materiél to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Red Army and played a key role in acquiring information that would assist the western Allies in any future conflict with the Soviets.

The TICOM project had been conceived by Colonel George A. Bicher, Director of the US Signal Intelligence Division, in the summer of 1944, and fully established by October when six TICOM teams were deployed in Europe to gather information about all aspects of the enemy’s activities in the signals intelligence (SIGINT) arena. Through the examination of documents and the interrogation of prisoners, TICOM uncovered the scale of the Reich’s cryptographic operations, which proved to be far more extensive than had ever been suspected.

The first exploitation team was dispatched in April 1945 to the Neurouenster–Flensburg area, and others were quickly assigned to different combat zones as soon as they were overrun. Approximately 4,000 separate German document files were captured, weighing 5 tons; large quantities of cryptographic equipment devices were secured and 196 PoW reports completed. Of particular interest were five SIGINT specialists who were interviewed at Nuremburg in September 1945. All the files and equipment were then flown directly to England for examination by Anglo-American analysts, who came to admire the professionalism of their adversaries.

TICOM’s research uncovered the complexity of overlapping organisations that had collected Allied signals traffic and then subjected it to prolonged analysis. German SIGINT specialists excelled at traffic analysis (T/A) and were particularly skilled at the associated disciplines of direction-finding (D/F), call sign analysis, frequency allocation, plain-text analysis and operators’ chat. They had also pioneered airborne radar route tracking, and the monitoring of transmitter zero beat tuning. Thus, before a single cipher group had been solved by a cryptographer, the analysts had accumulated a great deal of information about a particular signal and its carrier channel. Even if the text itself resisted attack, T/A could often identify the sender, the type of message, the operator’s location, the unit to which he was attached, and characteristics of the net on which he was transmitting.

The extent of the Axis investment in signals intelligence proved enormous and consisted of six principal organisations employing a staff of around 30,000. Italy possessed two main SIGINT agencies, with Finland, Austria, and Hungary one each, making a total combined strength of 36,000. In comparison, the Allies fielded an estimated 60,000, of which 28,000 were US Army personnel.

Four of the German organisations were military, being the Oberkommando des Heeres, General der Nachrichtenaufklärung (OKH/GdNA), which dealt with enemy army traffic; the Kriegsmarine’s Seekriegsleitung III (OKM/SKL III), which handled enemy naval traffic, the Luftwaffe’s Luftnachrichten Abteilung 350 (OKL/LN Abt 350); and the Wehrmacht’s Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Chiffrierabteilung (OKH/Chi). The two civilian organisations were the Foreign Ministry’s Cryptanalytic Section (Pers Z S), and Hermann Göring’s Research Bureau (FA), a Nazi Party agency that also dealt with diplomatic traffic, news releases, broadcast monitoring, telephone tapping, and other types of communications intelligence, irrespective of whether it was enemy, neutral, or friendly.

TICOM would produce a series of reports that were then, and remain today, the most comprehensive assessment of the Axis commitment to SIGINT, confirming that the source provided the foundation upon which other material was assembled, such as agent reports. Indeed, General Albert Praun, the OKW’s chief signals officer, asserted that most of the OKW’s actionable intelligence originated from SIGINT, not human sources, observing that, ‘In 1944–45 the results obtained by communications intelligence probably amounted to as much as 75 per cent of all the tactical information available to division commander.’1 However, Praun also acknowledged that Hitler and Jodl were often unimpressed by signals intelligence:

Throughout the war General Jodl, as well as Hitler himself, frequently showed a lack of confidence in communications intelligence, especially if the reports were unfavourable. However, orders were issued as early as the Salerno landing that all favourable reports should be given top priority and dispatched immediately, regardless of the time of day. Moreover, Communication Intelligence West was required to furnish a compilation of all reports unfavourable to the enemy derived from calls for help, casualty lists, and the like. Even during the first days of the invasion, American units in particular sent out messages containing high casualty figures, [and] the OKW was duly impressed. In contrast, the estimate of the situation prepared by the Western Intelligence Branch was absolutely realistic and in no way coloured by optimistic hopes.2

The Allied analyses revealed that the Germans had adopted a fragmented approach to the collection and processing of SIGINT, and that there had never been one single, centralised organisation to manage interception, traffic analysis, decryption and distribution, in sharp contrast to the Allied model. After a lengthy examination of captured documents and, having collated numerous interrogation reports, TICOM provided an overview of the various components of Axis SIGINT.

The OKH/GdNA, employing 12,000 staff and based at Juterbog, about 60 miles south-west of Berlin, was responsible for the cryptanalysis and evaluation of Allied army traffic, at any level whether strategic or operational, and undertook some radio broadcast monitoring. It was supported by two intercept stations targeted against high-level Allied traffic and nine field Signal Intelligence Regiments (KONA) assigned to various Army Groups to undertake interception, traffic analysis, cryptanalysis, and evaluation of Allied army low-level tactical traffic in the relevant Army Group areas. This was in addition to a small Signal Intelligence Section, assigned to the Army Commander-in-Chief West, which acted as a co-ordinating section for the two KONA regiments on the Western front. The unit issued three reports daily, circulated to the three High Commands (OKW, OKM and OKL) and to the Supreme Command, Armed Forces, to Heinrich Himmler, and probably to the Reich Security Agency (RSHA). These were also circulated directly to commanders at army group, army, and corps levels, and the nine KONA field units co-operated closely with their local counterpart Luftwaffe signals regiments. Until 1944, when the responsibility was passed to the OKW/Chi, the OKH/GdNA branch designated Inspektion 7/lV (abbreviated to In 7/IV) issued all the Wehrmacht’s codes and ciphers.

All branches of the German armed forces were heavily reliant on signals intelligence and much of the preparation for the expected Allied invasion was based on a very complex and comprehensive organisation. For most of the war SIGINT on the western front was the responsibility of KONA 5, until the establishment of KONA 7 in February 1943. Prior to February 1944, KONA 5 consisted of a SIGINT evaluation centre, Nachrichtenaufklärungs Auswertestelle 6 (NAAS 6), and four stationary intercept companies, Feste Nachrichten Aufklärungsstelle 2, 3, 9 and 12, as well as two long-range signal intelligence companies, Nachrichten-Fernaufklärungs-Kompanie, FAK 613 and FAK 624.3

The NAAS was based at St Germain-en-Laye and consisted of about 150 personnel, made up of interpreters, cryptanalysts, evaluators, draughtsmen, telephonists, drivers and clerks. It also employed some women auxiliaries who were usually assigned to the telephone switchboard.

Feste 2 was composed of a radio intercept platoon, a D/F platoon, and an evaluation platoon consisting of two sections: one for the assessment of content of messages, content evaluation, known as Inhaltsauswertung, and one for the evaluation of traffic, traffic analysis, Verkehrsauswertung. The unit had been formed originally to man the Wehrmacht intercept site at Münster, and in November 1944 Feste 2 amalgamated with Feste 9 and FAK 613 to form NAA 13.

Originally Feste 3 was the unit manning the Wehrmacht intercept site at Euskirchen but early in the war it had been subordinated to KONA 5. According to a member of its staff, Leutnant Hans Lehwald, it consisted of a radio reception platoon of approximately seventy receivers, and an evaluation platoon of twenty-five to thirty men. Evaluation was divided into a section for traffic analysis, cryptanalysis, evaluation, D/F and a filing section for diagrams of the radio nets, call signs, personalities, code names and D/F results. Later in 1944 Feste 3 would amalgamate with FAK 626 to form NAA 14.

Feste 9 was a stationary intercept company formed in Frankfurt in spring 1942 and sent to Norway in July, but was subordinate to KONA 5. It was posted first to Trondheim, then to Bergen, and in spring 1944 was transferred to Ski, near Oslo. The company consisted of a headquarters platoon, an intercept platoon of 120 radio operators, a D/F platoon, a radio reconnaissance platoon of about twenty men and an evaluation section with a strength of about thirty. The evaluation section was divided into a sub-section for the evaluation of message content, one for traffic, and one for cryptanalysis. Between the summer of 1944 and the following winter, most of the personnel were moved to Italy to join KONA 7.

Feste 12, consisting of a radio intercept platoon and a telephone communication unit, estimated at 120 men and 30 women auxiliaries, was subordinated to NAAS 5 until early 1944, when it joined Feste 3 to form NAA 12.

FAK 624, comprised of an intercept platoon and an evaluation platoon, was formed in Montpellier in April 1943 and attached to KONA 5. In February 1944 it was subordinated to NAA 14 of KONA 5, and in the late autumn was combined with Feste 3 to form the reorganised NAA 14. FAK 624 was equipped with approximately eighty-five vehicles with six special French radio trucks and trailers for D/F equipment. The strength of the company was roughly 250 men including interpreters, code clerks, cryptanalysts, radio intercept operators and ninety drivers.

In February 1944 FAK 613 combined with Feste 2 and Feste 9 to form NAA 13. When this battalion was broken up in late 1944, FAK 613 was reassigned to KONA 6, where it remained until the end of the war.

FAK 626 was established in August 1943, trained until January 1944 and was activated in Winniza. Its original mission was the interception of 1st French Army and US Seventh Army traffic, and later that of the US First, Third and Ninth Armies. It was subordinated to KONA 8 and was stationed in the Ukraine. In October 1944, FAK 626 was sent to Landau, where it was trained in western traffic techniques and reorganised. In November 1944 it joined FAK 624 at Landau, and both units were posted to KONA 5. The strength of FAK 626 on the Russian front was around 250–300 men, of whom 80–100 men were intercept operators, ten to fifteen D/F operators, ten to fifteen cryptanalysts, five to seven translators, and ten were traffic analysts.

In early 1944, when Army Group D was absorbed into Oberbefehlshaber West (OB West), which took control of three newly formed Army Groups on the western front, Army Group B (in northern France), Army Group H (in the Netherlands) and Army Group G (in southern France), KONA 5 was reorganised into three signal intelligence battalions, Nachrichten Aufklärung Abteilung 12, 13 and 14. NAA 12 was attached to von Rundstedt’s Army Group D, NAA 13 to Rommel’s Army Group B and NAA 14 to Army Group G. TICOM research established that Feste 12 had combined with Feste 3 to form NAA 12, and Feste 2 and 9 had amalgamated with FAK 613 to form NAA 12.

Even by the exigencies of conflicting wartime priorities, it is clear that the frequent movement and restructuring of the German SIGINT capability lacked continuity and mitigated against the creation of expert cadres that could concentrate on particular categories of SIGINT. Nevertheless, the scale of the resources devoted to SIGINT surprised and impressed their Allied counterparts, and the evidence suggested that special measures had been taken to develop a dedicated, streamlined SIGINT system in the west. However, the changes came too late to cope with the challenge of the invasion, and MI-14, the War Office intelligence branch charged with the daunting task of studying the enemy’s order of battle, was clueless when it came to Axis SIGINT arrangements.

KONA 5 remained unchanged throughout most of 1944 but later in the year, after the invasion, an attempt was made to centralise the western field organisation and a new senior communications intelligence post, the Hoeherer Kommandeur der Nachrichten Aufklärung (Hoeh Kdr D Na), was established with Colonel Walter Kopp attached to OB West, in charge of all SIGINT activities in the west, subordinate to Senior Commander of Signal Intelligence in the West, General William Gimmler. Additionally, KONA 6 was transferred from the Russian front to support KONA 5 and was assigned to Army Group B on the northern end of the western front.

When this change occurred, KONA 5 was reduced to just two signal intelligence battalions, NAA 12 and NAA 14. NAA 13, which had been composed of Feste 2 and 9, and FAK 613 were disbanded and their personnel redistributed. Feste 2 was placed under direct supervision of Colonel Kopp; Feste 9 was shifted from Norway to Italy, where it joined KONA 7; and NAA 12 with FAK 613 was assigned to KONA 6. However, KONA 5 gained one long-range intelligence company, FAK 626, which was withdrawn from KONA 8 in the east.

KONA 6, consisting of NAA 9 and NAA 12, had been created and activated in Frankfurt in 1941, and was posted to the Crimea. After the campaign in the Caucasus it was reassigned to work on the interception of Russian partisan traffic, and was finally transferred to the western front. When NAA 9 was withdrawn from the east in November 1944, it absorbed FAK 956, which had been established in October 1944, and the Long Range Signal Intelligence Company, FAK 611, which was also transferred from the east. This apparently endless process of reorganisation proved impossible to monitor externally, but reflected the strategic priorities of the Axis, such as the shift from the Russian front towards the west. Thus NAA 13 was assigned to KONA 6 from KONA 5 with the Long Range Signal Intelligence Company, FAK 613. Subordinated to NAA 12 were also FAK 610, which had been brought from the east in November 1944, and NAK 953, which had been reassigned from the east also in October 1944.

FAK 613 was given by KONA 5 to KONA 6 in late 1944. TICOM could not find out much about this unit, but concluded that most likely it was the same as other Long Range Signal Intelligence Companies.

FAK 6111 had been active on the eastern front during the Russian campaign from BARBAROSSA in June 1941, and had been stationed in Poland where it was attached to Army Group Centre. In November 1944, FAK 611 was moved to the western front and subordinated to KONA 6. NAA 9 was small enough to occupy a house at Zutphen, in the Netherlands, and consisted of thirty to forty radio and telephone operators, ten cryptanalysts and cipher clerks, and twenty-five analysts.

FAK 610 had been activated in 1940 for operations on the eastern front, and from September 1940 was based at Tilsit, subordinated to KONA 2. Later it transferred to Volkhov, where it intercepted Russian traffic until November 1944 when it moved to the western front and was assigned to NAA 13 of KONA 6.

These Wehrmacht SIGINT units, of which MI-14 had spotted only the faintest of traces, were considered by TICOM to be the foundation of all German intelligence assessments. Similar judgments were to be reached about the OKH/GdNA, as having accurately plotted the pre-war French, Dutch and British order of battle through a concerted cryptanalytical attack on the French codes and Dutch Army double-transposition ciphers, and through D/F and T/A operations aimed against the British Army. During the 1940 French campaign, with new opportunities offered by vastly increased traffic, it established the French mobile order of battle by cryptanalysis. OKH/GdNA also plotted the Red Army order of battle and located all the Soviet strategic reserves until 1943 through traffic analysis and cryptanalysis of the Soviet two-, three-, four- and five-figure codes, employed by both the Red Army and the NKVD.

Thus, by a combination of conventional SIGINT techniques, the OKW had developed a comprehensive British order of battle, and exploited the traffic generated by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to complete an impressively accurate wiring diagram of the entire British Home Army. In his assessment of British radio procedures, General Praun expressed a favourable opinion:

British radio communication was the most effective and secure of all those with which German communication intelligence had to contend. Effectiveness was based on World War I experience in radio procedure and cryptology, in which the British Army learned many a lesson from the Navy. The higher-echelon cryptosystems of the British were never compromised in World War II. The radio operators were well trained and performed their work in an efficient and reliable manner. Nevertheless, there were also some defects. Feeling safe because of the security of their cryptosystems, the British neglected to take into account the openings which their radio communication left to German traffic analysis. Plain-text addresses and signatures contained in otherwise securely encrypted messages revealed the make-up of the British nets and thereby also the tactical interrelationship of units in which the Germans were interested. The stereotyped sequence in which stations reported into their nets indicated the structure of the chain of command, while British field ciphers were too simple and did not provide adequate security over extended periods of time. Either the British overestimated the security of their own systems, or underestimated the capability of German communication intelligence. The same was true of the radio traffic of British armored units, which used such simple codes and so much clear text that the Germans arrived at the conclusion that the British were not aware of their field radio communications being observed.

In spite of impenetrable higher-echelon cryptosystems, excellent operating procedures, and efficient personnel, the security of the British radio communication in the United Kingdom during 1940–42 and especially in Africa in 1941–42, was so poor that, for instance, until the battle of el-Alamein Field Marshal Rommel was always aware of British intentions.

It was Rommel who repeatedly emphasized the predominant significance of radio intelligence reports in making an estimate of the enemy situation.

In this connection it may be pointed out that by no means all German field commanders recognised the utility of radio communication and intelligence. Many of them were quite prejudiced against these technological innovations. This may help to explain why the performance of some field commanders and their subordinate units so conspicuously surpassed or fell short of the general average. They were the ones who either deliberately or unconsciously simplified or complicated their mission by making full use of or neglecting the facilities which were at their disposal.

What surprised the Germans was that the many tactical successes scored by Rommel as the result of his unusually profound knowledge of the enemy situation did not arouse the suspicion of the British and lead them to the realization that their own carelessness in radio communication was at fault.

As in the case of the other Allied armies, the Germans observed a general relaxation in British Army radio discipline, particularly in voice communication, during the course of large-scale fighting. As a result, the secrecy which had been maintained up to the beginning of an offensive was quickly lost. A few other deficiencies continued to be evident in British radio communication until the end of the war, such as for instance the inadequate encoding of place names in connection with grid co-ordinate designations.

The surprise achieved by the British during their landing operations was remarkable. It was accomplished simply by imposing radio silences. The British Army probably acquired this device from [the] Navy.

Only in very rare instances did the British observe radio silence during ground operations. It seems incomprehensible why the British military leaders did not impose radio silence and use it in its more refined form, that of radio deception, more often. By achieving surprise, even during relatively minor engagements, they would have been able to reduce their losses.

In answer to the third question in this analysis it must be pointed out that even British radio communication was afflicted with a deficiency destined to compromise many of the Army procedures which had been so excellently devised and implemented. This deficiency was to be found in the radio communication of the Royal Air Force. The only possible explanation was interservice jealousy which led the RAF to overestimate the quality and security of its radio communication and to refuse to let it be subject to the supervision and control of the Army. At the same time Great Britain seems to have been without a unified armed forces command which would have restricted such separatist tendencies by exerting an authoritative, standardizing influence on the individual services.

The RAF was certainly not aware, however, that it was responsible for revealing many carefully guarded plans of the Army and thus for many losses and casualties.

Whereas the RAF failed to adopt the superior radio operation procedures of the British Army and Navy, other Allies who subsequently entered the war, especially the United States, introduced the proved British methods, much to their advantage. Only France failed to do so, much to its disadvantage.

During the last year of the Italian campaign the exemplary conduct of the British, with their wealth of experience, confronted German communication intelligence with a variety of problems. In this slower and more orthodox type of warfare strict control by the British achieved a high degree of radio discipline and was able to eliminate most of the national idiosyncrasies that characterized their radio communication. The standard of security in the Italian theater was extremely high.

Praun also commented on the US Army, although he was unaware at the time of writing that many of the supposed indiscretions in signals security that he had observed, and commented on critically, had been deliberately co-ordinated as part of Allied deception:

American radio communication developed very much along British lines.

Up to 1942 domestic military traffic in the United States and that carried on by the first units to be transferred to the British Isles, revealed certain distinctive features, such as APO numbers, officer promotion lists, end unit designations and abbreviations which were at variance with their British equivalents. German communication intelligence had no difficulty in driving wedges at points where these features occurred and in compromising the security of American radio communication. The manner in which the U.S. Army handled the traffic showed that its radio operators were fast and experienced. The comments made in the preceding section pertaining to the British cryptosystems are also valid for those of the Americans. The use of field cipher devices complicated German radio intelligence operations, even though their cryptosecurity was far from perfect.

The Americans deserve credit for the speed with which they adopted British operating procedures in 1942. They must have recognised the progress made by their Allies, particularly after El Alamein.

The Germans observed a continuous process of co-ordination aimed at eliminating the easily discernable differences between British and American procedures, except for linguistic differences which could not be erased. However, the radio discipline observed by the British and American units alike while they were stationed in the United Kingdom deteriorated rapidly and reached the very limit of minimum security as soon as U.S. troops entered combat. The abundance of radio sets with which the American units were equipped tempted the inexperienced U.S. divisions to transmit far too many CW and voice messages in the clear. They thereby provided the German command with many more clues regarding the tactical situation and U.S. intentions and enabled German cryptanalysis to solve many an American cryptosystem. This criticism pertains particularly to the initial engagements in North Africa, and to the subsequent actions in Normandy and France, and to a lesser extent to those in Italy. In spite of the training during combined exercises in the British Isles, the security of American radio communications was extremely poor. During the latter stages of the war the quality and security of radio communications was far from uniform in all the American armies. There were some armies whose radio traffic could hardly be observed, with the result that their intentions remained a secret. Other armies, either deliberately or unwittingly, denied themselves the benefits of radio security. Needless to say, in spite of their obvious superiority, this deficiency proved detrimental to them and resulted in needless losses.

The comments made with regard to radio silence and deception in the section dealing with British radio communication apply equally to that of the Americans.