Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

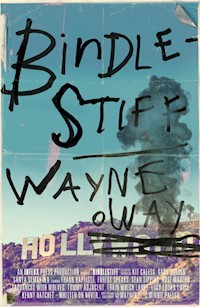

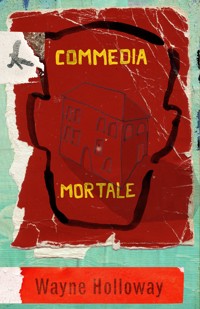

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'"Idiosyncratic" doesn't begin to get near him' – Guardian Liguria, Italy. In a mountain village sits an old farmhouse that stores the memories of those who have lived there and suffers the tales of the visitors who come and go. The house weaves its magic on all who encounter it. New owners move in and over time become entangled with a parade of oddball characters. From pagan ritual to the antics of modern village life, the clash between outsiders and locals, Commedia Mortale seeks to understand what is authentic in both: the tall tales of ageing Second World War Partisans, the dreams of a chef to travel to parts unknown supported by a Greek chorus of drunks, a talking parrot, and asylum-seeking footballers with their own dreams, and miraculously a visit to the village by Anthony Bourdain himself. Parsed through the eyes of a film maker, the ultimate outsider, Commedia Mortale summons dreams of kinship and nightmares of enmity. Ranging across philosophy, food, history, love, loss and landscape, Holloway conjures up a unique portrait of a place, the fables of its past and the dilemma of how to live now.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

COMMEDIA MORTALE

Wayne Holloway

Influx Press

London

4

5

‘The desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews.’

— W.H. Auden, ‘Death’s Echo’

Contents

7

Prologue

Stregone

After an afternoon swimming in the river I was desperate for a cold beer. My tinnitus was equalised by the sound of rushing water, the experience of near silence in my head always energises me – only the crashing of waves surpasses it – but it was a steep climb back up to the road, hot and humid. The bar served Tuborg Gold on tap. A brand that speaks to me of nothing. A strong beer with a bitter, chemical aftertaste but cold and amber. So I ordered a media and sat outside on the narrow balcony with a zinc bar top overlooking the valley and the thread of road, town and terrace that bisect these mountains as they twist, turn and slope, becoming hills before running out onto the coastal plain. The balcony perches above it all, certain death below if it were to fail, and there is not one drinker who ever sits here that hasn’t imagined how many people it would take 8for it to collapse under their weight or what misalignment of stars could bring about sudden disaster; steel rebar – compromised somehow – or rotting concrete badly mixed when first poured conspiring with temperature and humidity to precipitate catastrophic failure.

Sitting here was always a trip in itself.

I sit alone – it was my fate to do so – spaced out, buzzing from the sun, numbed by a day of doing nothing under it, punctuated by refreshing dips, the sense memory of that, of cool water on hot skin, distracting me from opening my book on a balcony held up as if by magic, a panorama of the whole valley at my feet, a scene so varied in shape and colour that it would make a fiendish thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle.

Sun softens the mind, enabling free association of words and thought. We respond to it as if swamped by drugs; a rush of serotonin our reward for providing the body with its daily fix of vitamin D. Addicted to its pleasures, we are literally sun-spanked on peptides.

Two men come inside – I see them when I get up to order another beer – backlit by sunshine, momentary silhouettes that quickly resolve into people. The younger one is dark, with dense curly hair tamed under a jaunty bandana with a faded red and yellow pattern, a sleek black feather tucked behind one ear. He wears billowing blue pantaloons and leans on a dark wooden stick, which reminds me of an embossed Rastafarian swagger stick, redolent with meaning, but this one was more Lord of the Rings, its bulbous head a natural knot in the wood rather than something worked. A precocious stick. One last detail: he was wearing lime-green North African slippers.9

Imagine preparing the props and wardrobe for a big scene in a blockbuster movie like Pirates of the Caribbean; so say there are three levels of detail or elaboration. Main players, featured extras, and then general background – think close-ups, mid- and wide shots – the latter having no need for jewellery or any small detail that would only be picked up in close-ups, so just the odd hat or scarf thrown in for colour variation. Featured extras were tricky: you could waste time on them, or indeed be caught out in the edit suite for overlooking them. They required some styling, props, but nothing too elaborate.

This guy was more of a featured extra. At a glance he looked the part from head to toe but wore no bangles and I didn’t notice any earrings, necklaces or tattoos for that matter, something usually reserved for the main players as they were time-consuming to apply and a bitch to get right. The feather was probably his own touch. Something he brought to the party.

The other man was slightly older – or just more weathered – blond, thin on top with a light moustache and bare dirty feet, his ripped jeans more like ragged curtains framing each leg. He had a faraway look in his eye, whereas the darker one was intense, his eyes – olive-stone shaped and jet black – darted over every surface scanning the room. The blond’s eyes were pale blue. Shifty, they didn’t rest on anything for long, giving you the impression that he wasn’t really looking at anything at all, his eyes were lit from elsewhere, reflecting a different scene altogether.

Asphalt sears the soles of your feet, literally hardening them for modern life on the streets, tempering them against slivers of glass and metal, diamonds of grit and stone, shards of brick, bones and 10the ooze of rubbish. These tempered feet are paid for in a silent currency of pain, paid in full and worn, if that is the word, worn with indifference, perhaps resignation, but never pride.

I returned to my spot on the balcony and picked up my book, The House on the Via Gomito, which was taking me weeks to get through, to the extent that I was bogged down in it, so any distraction led me to put it aside. The two men – two men sounds odd, they didn’t strike me as such; although boys or youths was factually incorrect, there was something essentially naive about them – came out onto the balcony a few minutes later with two glasses of water and a single cappuccino on a small tray. We said hello and one of them mentioned the view. I offered a slight smile in return. I tried to focus on my book but I found myself drawn to their conversation. They spoke in a polyglot of Italian, Spanish and English.

– Great spot isn’t it? The blond gestures, sipping his water and whispers,

Almost a mirror.

The other one sipped the coffee before rotating the cup and offering it to his friend. He had an old metal tobacco tin and spent minutes sifting through the dark dry tobacco, finally rolling himself a cigarette. Through this action he sought to own time, shifting us all sideways in his direction. The blond prosaically smoked a straight, almost finishing it before his friend licked the paper on his.

I am really drawn to your energy, I feel your aura.

Said looking out to the mountainside opposite, as if addressing it and not his companion. (Or maybe he was talking to the mountains, it would make more sense?)

By his words and actions he ceded power to the younger 11man, despite his rollup being a disappointment. With his energy and fierce eyes I had expected the tightest, straightest pencil of a cigarette, something perfect. In fact, it was badly made – bulging in the middle – amateur, a hastily prepared, last-minute notion rolled on the hoof as it were by a set dresser or prop assistant seeking to make a good impression with her (unnecessary) attention to detail and her understanding of background action and its unpredictable on-screen visibility.

The cigarette trailed loose threads of tobacco, he didn’t even pinch them off. When he finally lit it they flared away trailing tiny sparks. It smoked badly and he had to suck hard to keep it going. With a simple look, a raising of eyebrows, the blond could have rebalanced the scene in his favour, but he didn’t.

Here, have one of mine…

Would have clinched it. Instead he continued…

I felt it as soon as we met.

I should say that this is a rough translation of what he actually said, two sentences cobbled together from three languages. Almost a mirror might have been take a look at yourself in the mirror; whether literally in reference to the mountain opposite or figuratively, meaning take a look at yourself. I didn’t invent this bizarre phrase – I’m not putting words in his mouth – that would have been odd, to want to do that, to make up something like that just on first impressions of this unlikely double act. No, the key words were definitely spoken; a mirror, the reference to another person’s charisma and him being drawn to it. The sense of the latter was not sexual nor did it come across as submissive, I intuited neither of those inferences. There was an increasingly odd flow of energy between them.12

The dark guy finally gives up on the rollup, which died at the bulge. His fingers claw a straight out of his friend’s proffered packet.

The acolyte leans in to light it.

I really want us to work together, so we can amplify each other.

For fuck’s sake.

With this the blond recused himself from any potential kudos. I smile as if reacting to something I had just read although there was little mirth in The House on the Via Gomito, the story of a childhood lived under a violent imperious father. Yet I had kept with it, rubbernecking the car crash of this family saga over at least four hundred pages leavened by at least three other easier reads, none of which I can remember by name, something contemporary and Japanese and a horror story, yes definitely a horror, a bloody tale soaked in South American tribal curses and witchcraft, the vulnerability of our insides…

The house itself, its rooms and balconies and the close proximity of the people who lived there, is what kept me reading. The way in which they frame our lives, capture us in their memory, as much as we inhabit them in ours. This amplified itself across the books I was reading simultaneously, with their houses of horror and refuge respectively.

The blond guy was now talking up a storm, about a fresh start, things to overcome, hurdles both inside and out, the challenge of setting out on a new path, about his job, the farmers he worked for, how in this valley the opportunities were endless…

All I saw was dirty feet and a shared coffee, sipped from both sides.13

Who were these two? Perhaps novices best describes them. Whatever it was they were novices at made them behave like tentative children. They were new to this, to speaking unusual words. Imagine wet clones straight out of the vat in a show like Star Trek or Altered Carbon, sleeved fully grown yet as naive and innocent – momentarily – as children, slick and fresh from the amniotic sack. What power could either of these two men really possess? One in rags, the other slightly ridiculous. Summer hippies in a mountain village where it is cheap to live, the detritus of the wealthy North freewheeling down to the Mediterranean as they have done for decades. Or had the dark one come up from the South, from Spain, or further, the enclaves of Morocco? Perhaps whatever simmered between them was a clash of the compass rose, a hot sultry Scirocco riding up over a cold blustery Tramontana? A silent yet seductive southern breeze, for I realise he had yet to say a word, communicating only with his eyes and twitches of lips, which are thin – surprisingly not full and sensual – parallel lines like the ridges of a walnut, intricate and mysterious.

Winds of a different temperament.

I lose interest, finish my beer, the last mouthfuls warm and unpleasant as I ponder another, a buzz beginning to build behind my temples, pleasant and familiar. On my way back from the bar I catch…

This is my new home.

Said with a hint of him being profoundly surprised to find himself there. A prosaic turn of conversation. It crossed my mind that perhaps the other’s silence was more a lack of comprehension than charisma. If so, the blond was wasting his time, or perhaps indulging his own fantasies, projecting a 14need in himself onto this relative stranger, who, in his eyes at least, looked the part of something he was looking for.

The blond was not lost, he was too wily to be lost, but he was searching, whether he knew what he was looking for I couldn’t tell. It wasn’t for me to see it. He was still in the dark, yet confident that he could talk his way into enlightenment. The dark one smiles and listens. He enjoys the chatter without the need to add to it. Oddly, I instinctively trust him. I admire his ability to be quiet yet encourage others to talk, to enjoy that without judgement was a subtle power, a rare strength of personality.

Words are heavy, they weigh us down, what we say implicates us by revelation. Silence is light, mysterious, it soars. Without speaking we can weave spells that strike those below with the surprise and ferocity of an eagle predating a rabbit.

I realise that on some level he is waiting for the blond to talk himself out, like a shrink who listens and speaks rarely, if at all.

That summer I was in the middle of writing a pilot for a TV series set in the world of fantasy wargaming, an almost invisible subculture where the awkward, the nerdy, the misfit, the non-binary (in the broadest sense), the waifs and strays, find a place in which they feel free to express themselves. In a word, to live, and have fun just like everybody else. And then this world is discovered. To be monetised/molested for all it is worth and the oddballs become leftovers; half of them are culled, priced out, others make themselves over into cosplay norms, willing victims of the film/TV/game franchise circle jerk that is at the heart of the ludo/entertainment/industrial complex. What’s left, the holdouts, radical hardcore nerds, the heroes of my show, 15have to fight to stay in the shadows as the margins themselves become commodified.

Two waters and one cappuccino.

Wally Hope, another outsider, born on Ibiza, the white island, in a house where his mother kept a locked room full of his father’s Nazi paraphernalia. He grew up a different kind of a pagan, an organiser of festivals, happenings, and a seeker of truth through being in the world just like the two men sitting next to me. Or was there just one, who invoked the other? Or perhaps none, was I imagining them both? Had I been in the sun too long, had my mind wandered too far? Wally had summoned a snowstorm in midsummer from under his cloak, hastening the tragic end of his life. There are people who will swear that it was so, the snow, his swirling cloak in a summer garden in Essex in the 1970s, and I wanted to believe that, for reasons of romance, but more than that, to fill the void of it not being true.

Had the blond invoked, willed the other into existence to serve him, or – which is more likely – just to provide some company? This lonely outsider, with bare feet and broken toes, thirsty like I was upon entering the bar, asking for two glasses of tap water to quench his thirst. The success of his summoning enough to cheer him, like Wally and his snowstorm, manifestation for its own sake, for pleasure.

He pays for the coffee, catches me watching his friend and smiles conspiratorially, as if to say: you see him too, right?

A warlock in peacetime.

At the door, just as he is about to step back into the sunlight, the silent one pauses, looking back towards the perilous balcony. His stick sends its shadow slashing across the floor, casting a benign spell, or so I choose to believe and 16by doing so keeping the peace. For there are many peaces which hold or are broken in every place and at every time, big and small, some visible but many less so, as fragile and quotidian as the things and the people that keep them.

This is mine.

17

Istvan

On the exterior wall of the house, overlooking the valley, is a life-size plaster bust of Istvan’s head and shoulders. He has a narrow face with a sharp pointy nose and chin. An eighteenth-century face, suggesting Voltaire perhaps, the outline of his hair reminds me of a periwig. It suited his narrow features but perhaps this was just sloppy casting. Istvan overlooked the terrace for ten or more years until a storm blew it down, leaving a jagged stump, a nub, what was left of his neck and shoulders. This has since fallen away but I remember it more than I can recall his actual likeness.

In the valley a storm can mean the sky emptying a bucket of tennis-ball-size hailstones in the space of minutes, out of the blue – literally out of a blue sky just minutes before – smashing bonnets and roofs like a crazed ball-peen hammer attack, ending abruptly as we exodus our vehicles discombobulated into returning sunshine, the incongruous 18marbles of ice to be broomed to the sides of roads in banks of slush, flooding the roads an hour or so later. The sort of natural event that is ridiculous, that makes you laugh out loud. Although I suppose one of those stones could kill you, could definitely kill a child; an absurd way to go, the worst of luck, like a coconut falling from a tree in the tropics (which nearly killed Keith Richards, among countless others) or a pane of glass falling onto the pavement in a city, missing passers-by by inches or severing their heads. The odds are long yet getting shorter. If you live in nature it is more likely to kill you. Fire, drought, flood and famine. Typhoons, for example, catch you out in the open; you run from them or cower in flimsy barns to little avail.

Istvan’s self-portrait didn’t stand a chance.

Fragments of his work can be found all over the house. I mean the work was fragmentary; he worked in fragments. Primary colours painted on found objects – slashes of yellow on a piece of slate, a hole drilled through a stone, the inside painted a lurid green, white, black stripes, bold circles perfectly cinched around rocks – visitations of colour and form. On the first-floor landing was an old, handmade wooden box with many drawers meticulously outlined by a fine brush in red, which feels alpine – red paint on sanded wood – as if from a chalet higher up in the mountains, although I’m not describing it very well. Each drawer – they didn’t fit perfectly, swollen by damp, you had to worry each one in and out – was full of small household objects like needles, spools of thread, biros and pencil stubs, faded business cards from local restaurants and taxi firms, shopping lists, a drawer full of nails, another with faded unsent postcards but also a few received, tantalising 19glimpses into another life in full quotidian flow. Written in German and Hungarian, warped by time; greetings, wish-you-were-heres and see-you-soons.

All unsere Liebe dieses Weihnachten 1986.

Upstairs was a bookshelf full of art books from what looked like the 1970s and ’80s, black spots of mould peppering the spines and front edges as if fired from a shotgun. Stiff, crooked volumes propping each other up as the damp worked on them, a collection distilled from a lifetime spent in the art circles of central Europe. Monochrome photographs of mostly naked, hairy men and women, posed in tableaux or as part of an installation or captured in blurry snaps taken at happenings, in basements or warehouses, probably clandestine; performance art that involved the body, paint and big ideas.

The house shares rocks and stones with the mountain it is built into. You can’t disentangle the two, they are conjoined twins – house and mountain – sharing the same mother.

Istvan had scribbled this on a postcard – in English, for some reason – I don’t know how many languages he spoke, but he was Hungarian by birth and lived in Germany. His paintings that years later I discovered online reflect an ongoing fixation with this entanglement.

I met him at the house for the first and only time to pay the balance of what I owed him. I had already deposited the taxable sum with a lawyer in his office on the coast.

It was Easter, more wet than cold, but I found him sitting in the dark cantina hunched inside a big overcoat. I sat down opposite him at a rickety kitchen table drilled by woodworm. I ran my finger across the braille of it. He stood bolt upright to remove his coat as if I had sat on the 20other end of a seesaw, my weight somehow displacing his. Under the table I smelt then saw a mangy old Labrador fast asleep. The walls and ceiling were a dingy stained Artex. The cottage-cheese-like appearance was immediately oppressive. It felt like it could drip on us at any moment.

– Hello.

A shake of hands. A strong grip, smooth palms, corded arms.

– Guten tag. Welcome to Casa Istvan.

His hand gestured to the room, perhaps ironically.

This had been a place for animals: cows, sheep or donkeys, who I imagine would have been happy here. He had opened a bottle of wine for us to share before he left. It was half empty and he was already drunk. As he poured me a glass, I noticed a patchwork of old white scars and more recently healed over red nicks on his right hand, wrist and fingers. He could have been a farmer in another life, is what I thought, sitting as we were in a farmer’s house, although what would I know about that? His left pouring hand was relatively unscarred but had a slight tremor and the neck of the bottle clinked the glass a little too hard but without chipping it or spilling a drop. An artist, a drinker. The whole place felt like an installation from one of his books. In the corner was an open fire, but I don’t recall it being lit. Easter fires were usually smoky, the rain pushing down on the chimney to billow smoke out into the room. A single bulb hung low over the pitted table. Who knew how long he had been sitting there with his dog; a still-life tableau. I don’t remember what we talked about. The house, probably. He wasn’t the sort of person to give any tips. 21Definitely not his art, which I only noticed after he had left. He didn’t mention it. I assume he wanted to finish the wine, shake hands and take the money. I remember the physicality of the money itself because it was the first year of the Euro. The notes were brash, cartoonish, extra-large and felt like plastic; invented for the performance of exchange. They didn’t tear, you couldn’t easily rip them. By comparison the pounds in my pocket were old, clipped and fusty, clandestine currency worn down by use and sullied by too many hands. Notes aged like we did, especially along their folds. These crisp Euros in Istvan’s hands looked out of place, a prop master’s mistake in a low-budget movie, or perhaps the product of a fresh surprising optimism, gifted from a potentially bright future.

How much was it? I have always thought it was twenty thousand Euros. That figure feels right but how would I have given it to him? In a holdall? I have no memory of the mechanics of exchange, just him sitting there a bit withdrawn, dismissive even. If I gave him forty five-hundred-Euro notes, then perhaps this was doable, but again, I have no memory of it or of getting this amount from a bank. I do not know what a five-hundred-Euro note looks like but the house exists; it is ours, and the amount shown on the deeds – sixty thousand Euros – was not the full amount. There was definitely no bank transfer, which, to be frank, would have jeopardised the mutual goal of tax evasion. A large amount in whatever denomination would have had to be checked a few times, whirring through the machine, or did the teller pass the notes from one hand into another, right under my nose as it were, fingers licked to count methodically? I remember none of it.22

However I came by it, I gave him the money, disappointed that it wasn’t bundles of lire. Proper money. I remember them fondly as I do pounds, pesetas and francs, a true union of European lucre. These old lire – like snot rags in your pocket, crumpled up, greasy, ripped, folded origami-tight, bundled with elastic bands – cash that stank, of sweat, of hard work or slick with the adrenalin of easy money pocketed quickly and spent without consequence. Sad single notes or a couple of coins retrieved from the bottom of purses, from deep pockets lined with lint. Coins and paper worn from constant use, intimately warm from the desperate passing from hand to hand, or damp, lifeless, sequestered in a shoe box, squirrelled away, perhaps forgotten, acquiring the odour of wherever they had been kept safe, of lavender, a dry linen bag at the back of a drawer, the stink of animals – shit or milk – if hidden in farm sheds or behind rafters in hay lofts, or the acrid smell of old motor oil from being counted into a mechanic’s hands or the sweet note of tobacco or biscuit if stashed in a tin. All of this teeming life, the life of money, our life – money in pay packets or freshly printed stacks of notes mustering in a vault, like mint trainers destined to become scuffed, worn and just like us, destined to carry their experiences as they make their way in the world, the scars, the memories running through them and us like liquorice in a stick of rock; money that sticks to some people and not to others.

I would have remembered that.

Euros have no character, only function. Come to think of it, the teller has no reason to lick his fingers before counting, they are designed to separate with ease. Now real money is to be found elsewhere, in India, South America, places like 23Kazakhstan, Ghana, Vietnam. Even the mighty dollar has remained unchanged. The last vestiges of proximity to money, our sensual relationship with it. We are just left with the ghost of exchange, ephemeral notes and coins not storied enough to hold out against a cashless future.

My friend Paul arrived at the house, he had gone to get cigarettes from the new machine in the village. So long ago, it was a time when we smoked without thinking about cancer, or to be less melodramatic, we smoked without the shadow of mortal thoughts crossing our mind, which is to say we smoked pleasurably, guiltlessly, that’s how long ago this was and how young, relatively, we were. He helped us drink off what remained of the wine. Istvan left with his money in an ancient jalopy, which didn’t make it further than the first turn on the gravel lane before conking out. We helped him push start the car. Three times it took for the engine to catch, and the car finally lurched forward. The last I ever saw of him was the back of his head and the knuckles of his hand out of the window waving goodbye and the dog sitting up front as the car spluttered its way up onto the tarmac road and off down the hill, on his way, implausibly, to Budapest to visit his brother.

Concrete moments in time, although somehow listless when translated into memory. In the sense of being flat-footed, having lost the anima of the detail they contain, the transient play of light, movement, colour and smell, the conscious expectation and outcome that only occurs once in cosmic time, then dulls, degrades over a lifetime of being just a memory. No longer in the game of life, like money that has changed hands for the last time. How many times can you remember something before the currency of it runs out? The same thing, the same event, either so flattened out as to become 24rote, with exactly the same details, or the opposite, a shifting series of memories of the same thing but really not the same thing at all, and therefore not fit for the purpose of recollection, downgraded by the vagaries of connotation. A compressed Jpeg, filed away among millions of others to be resuscitated by words, to be used rather than cherished, useful when placed in a story they don’t deserve to feature in. And how can one memory ever be discrete from another? They are not inviolate palaces but rather violated prisons, and we the thief, pickpocketing ourselves. Life bleeds, spends itself recklessly, regardless. It is uncontained, we can only imagine it from the debris of recollection.

In that first year – a year of boundless enthusiasm and energy, not to say money – we got rid of the Artex ceiling and pulled up the cream tiles that looked like wet tobacco ends from rollups had been smeared on them. The artworks remained, part of the fabric of the house, subtle details of Istvan’s presence until entropy or accident removed them. Then only one was left, a strange flimsy-looking canopy made from wooden slats wired together like rotten teeth, hanging over the front door protecting a single light bulb that still works to this day, a little miracle.

Cemented into the wall to one side of the door is a piece of slate with the chiselled legend Istvan Laurer 1984.

All of this lent a recent hinterland to the house without defining it. The house was inviolate, however much we tampered with it. It didn’t shrug you off; it was a benign presence. You lived in it, easily. It had never been a blank canvas, nor somewhere that demanded to be filled. Its shape was enough. There was a solidity to it that reassured you: the walls were two feet thick. It had ceiling arches which 25reminded you of churches, a similar sense of permanence. This was the house, the character you experienced, not the things people had put in it. Things and people were transitory if not irrelevant. In summer the thick walls absorbed heat from the sun, keeping the interior cool. At night they released it, like some kind of battery, the walls were hot to the touch until past sundown. You could feel the pulse of it up to a few feet away. Istvan had felt the pleasure of it and now we did. A small, robust memory. Just that, the heat from stones on your hand at night. He took his share of that pleasure with him to Budapest.

I had been to Budapest in 1984. The same year he bought the house and chiselled his name to prove he had done so.

Perhaps Istvan chuckled to himself as he laid those bloody tiles before sunning himself like a pig in shit on the terrace. How many things do we do in our lives, happily oblivious to the fact that somebody else will come along and undo them, replace them, cursing us?

Buda and Pest. A city bifurcated by the Danube, two different places, one medieval, the other nineteenth century. Europe and the Orient, the croissants served in the cafes of one celebrating the defeat of the other. The old town and the new, bound by bridges. I remember the stories that spill from this city, spun from other people’s memories and served up as entertainment or admonition, along the fault line of story…

Nobody pays the ferryman, the bridge stole his income; an old story already told by another.

The horror of the six-year-old Jewish girl ringing a service bell six floors up from the kitchen to order lemonade and sandwiches, hungry or just for the hell of it, an expression of 26power and powerlessness. The maid, the servant, ridiculously young or perhaps very old, traipsing up and down the stairs to this unhappy girl’s every whim. Oh was she deliriously happy – wielding the power to wear out the soles of another’s shoes! – while at the same time being inconsequential, a little girl in a big bad world as 1940 counts down to ’44. The servants’ hatred or indifference a yardstick of her success or failure. I try to worry meaning from it, circling the story over and over, teasing new details each time as if they would unlock a bigger truth hidden within and the rest would all tumble into place. For what? Insight? Understanding? Of whom? Why else recount it? Am I sick? I imagine this place as a tower, of course, a girl in a tower, the servant feeling dizzy resting halfway up or down the spiral staircase…

The summer of 1984. I was interrailing with my first girlfriend; we roamed all over Europe that summer. Our first communist city, a city without advertising.

In another Hungarian town, Pecs – south near the Croatian border – we met a young Soviet conscript. He wore a military hat with a huge brim, set at such a jaunty angle on his head that it defied the laws of gravity. In a bar we traded stories of growing up in England and Odessa, chased by vodka and beer until finally he took off his shirt to reveal a tattoo of Stalin spread across his pimpled back, the beady eyes and beneficent smile flexed between his shoulder blades. The boy’s face was flush with pride as he tasted victory, for what could we show or do to match that? Although I did notice him glancing frequently at my girlfriend’s breasts.

I wondered, would he be so happy in thirty years’ time on a beach with his grandkids? For me that tattoo was an 27early intimation that our youth would dissipate. It wouldn’t always be like this, but what would it be like? It was right there in front of me, Stalin mocking us for our callowness.

And galloping on horseback across the steppes to Baku, and destiny, to win or lose, live or die, immortal twenty-two…

It kind of killed my buzz back then, on that hot summer afternoon in Hungary. And today – whenever that is for you – I imagine that conscript, now a post-Soviet Ukrainian citizen, middle-aged and under fire, a volunteer, too old to be conscripted, occupied or occupying, dead even, bearing the sigil of another world reclused under his shirt, no longer immortal.

Or perhaps he is sunning himself on the beach, T-shirt on, somewhere out of harm’s way, on the Caspian or the Black Sea.

Grandpa, why don’t you take your T-shirt off, it’s so hot!

A sly smile passing between father and son under the parasol. The son shaking his head.

Or.

At a Ukrainian checkpoint.

Fingers fumbling with sweat and fear, undoing shirt buttons at gunpoint. Fat fingers, sweaty because overweight, out of shape, on the verge of becoming eternal.

My mind circles, I can’t help it. Was the tower I imagined the little girl lived in a symbol of destruction? The fallacy of power, like in Tarot decks – which I hardly know anything about – towers like cocks pointing to your doom.

She w/rung the shit out of that bell.

Back then I visited Budapest without the weight of memory, we visited bars in the ghetto, not looking up for any towers, real or imaginary, living our young lives from 28the perspective of the street and no little wonder. Now I can’t wake or move without its hand upon me, not a guiding hand – how could it be that? – but a dead one.

Thirty years later I google Istvan Laurer for the first time. In my mind’s eye I remember a Joseph Bueys character – the ex-Luftwaffe pilot artist who had sat in a cage with a wolf – Istvan, whip thin, rolling skinny cigarettes with liquorice paper and pungent tobacco from a grimy leather pouch. He looked old then, in that dingy room, but looking him up he must only have been in his fifties. His hammer and mallet hands and disfigured fingers producing the most perfect of tight rollups.

Et voila.

My age now.

Istvan had bought the house with his German partner who was a banker. Ten years later they split up and eight years after that he sold the house to me. He left here to visit his brother in Budapest.

In that car.

Good luck.

I wonder if he got to see his brother and how long the money lasted. Beuys had survived a plane crash in the Crimea, rescued from the flames by Tartar tribesmen, or so he says. Did Istvan make it home, also in one piece albeit exhausted, with a pocket full of money, to change into Forints and spend as he saw fit, or so I imagined?

Online, his photos are very much of a kind. Portraits of a serious mid-century white male European artist staring either into the camera or just off it, smoking intently with his work in soft focus behind him. Scruffy, important-looking studio spaces, full of performative creativity; 29kinetic spaces in which the artist is busy making. His open face reminding me of Oskar in The Tin Drum. In fact, there is a headshot of Istvan as a boy and he is the spit of Oskar, perhaps the go-to face for mid-century middle European children, ripe for AI farming, generating skins for gamers on apps like Midjourney, the prompt being:

Malnourished / war child / high forehead / blue eyes / twentieth century / Russia / Germany.

A precocious face. Arms crossed over an open book. A prodigy reading a book from a private library. Or was it a professional photographer’s prop? A tome made from cheap rag paper. A little cheesy, a little too much Hans Christian Anderson.

White is a default for many of these algorithms so I wouldn’t have to prompt that, and if you type Jewish (which you might for this look, from this time and place) then this is flagged. As well as Oskar, his stark presence in the photographs reminded me of the boy Flyora in Klimov’s Come and See, the go to face of mid-century horror.

The paintings are mostly circular, something I don’t like, an odd aesthetic. I couldn’t tell you the meaning of their content, some figurative representations of animals, birds of prey, tropical birds also, parrots, flamingos, very colourful; a lot of greens, bold colours, kitsch, perhaps not far off early Kate Bush album covers, so a shared ’70s sensibility, planet aware, a distrust of human politics, I’m not sure. Tendrils also, the profuse fecundity of nature entwining us; you can see this in his work.

Our house was literally part of the hillside. In the spring and autumn, rainwater flowed down the bare rock walls of the stairs until I got somebody to wall it in. The kitchen 30flooded regularly, water bubbling up randomly, yet in summer and winter it was bone dry. The seasons passed through the house and the house rode the seasons, shrugging off whatever nature threw at it.

As we age, the place we live in stays the same. (If we can afford to stay in the same place, or not afford to move from it.) After a certain time we rarely change things or redecorate, the pictures on the walls stay where they are permanent shapes on the wall; we stop refreshing their arrangement, we hardly notice them, they belong to the house. It’s us that change. We no longer live in it in the same way. Things fray at the edges, small jobs go undone, disrepair adds up. The house gains a certain patina. It’s a second skin perhaps. Physically we make small changes, add extra bannisters to help us get upstairs, perhaps do something in the bathroom, slip mats, handholds, etc., but emotionally the shift is greater; we can’t help but haunt our previous life. The house we made love in, had our children in, the patterns of our lives now out of sync (ever so slightly at first, but then…) Hallways we tiptoed down drunk, late at night; the desk where we used to work; the corner we always caught ourselves on, the nub of a nail or carpet staple on the stairs, the same small wound on a wrist, arm or ankle, repeated over years. A house also has many psychological facets, atmospheres, vibes, generated in the dining room or kitchen where we entertained. Memory conspires with the house to suggest our time in it is nearly up. To chide us, and not just for the tiredness of decor, the dust and neglect. Our lives become an intimate study of how time passes in space, our private space observing us more than we notice it, the Hubble telescope of the home.

The tables turn and we become the ghosts of entropy.31

Istvan Laurer 1984.

No mention of his partner’s name, it was his house. What he left behind seemed so benign I didn’t feel the need to find out more about him for twenty years. Perhaps the anniversary of having the house prompted it, or just getting older, like him. I even got a tattoo on my forearm that year.

Forza Agaggio.

Venti anni.

Which is why I nearly missed it, an archived gallery website of his work on which I found paintings of the house, the shape like a children’s drawing framed by the three cypresses on the terrace. An oblong outline, six windows and a front door, exterior side steps to the right and V-shaped roof, the moon behind it. (I have never seen the moon behind the house, it is always in front, traversing usually from left to right and back again at all times of day and night.)

Istvan couldn’t stop painting or drawing the house, some date from when he was there but mostly in the years afterwards, from memory and becoming more fantastical, the last dating from 2010.

Archived websites are like houses in which we become archived, nothing is added or taken away or moved around anymore, nothing updated or refreshed, websites that are haunted by our absence, achingly evocative of the more we could have done.

If you stare into the abyss long enough, it will stare back at you.

I think a man like Istvan would have read Nietzsche. I haven’t, other than a few mis/quotes, like there ain’t nothing Nietzsche couldn’t teach ya, a lyric from somewhere, a song, long ago…32

Forest fires are a problem up and down the valley in the summer, and if you make bonfires, you get heavily fined. Istvan must have done this in late autumn, warmed by wine on a cold and starry night. The fire caught, racing up one of the trees like a candle, and they had to come up from the village to put it out and to scold him.

Crazy Istvan. He ran about half-naked up there.

It is the only story I heard about Istvan from Gino, a farmer who has olive trees on terraces below our house of which he was protective, so this is a story he would tell.

The absence of the third, although there is a stump. The two remaining trees identify the house as ours more than the house itself.

I can see him stumbling about the terraces at night, drunk, smoking, howling at nothing, for I have done it myself, a pleasurable release.

His paintings have a decorative style. The perspective is flat and antirealist, kind of like Chagall and Japanese block prints, the innocent framing and bold colour blocks of Gauguin. So the moon, or what represents the moon and gives directionality to the shadows, can be where he wants it and them to be compositionally, without recourse to compass or the natural procession of the sky at night. He chose to place it behind the house, lighting it for us. I don’t write about art often so don’t know the common terms, but this is what I see: he foregrounds the terrace, which is where we spend most of the time. In real life he extended it; it was his stage, a place from which to scry the world. And it looks exactly like that in the paintings and now I also scry the world from there.

In another painting the house is framed inside an outline of a head, I assume his, with the side steps clearly visible 33and the moon and stars reflected onto the terrace as if onto a pond or a purely fantastical body of water, a full green moon side by side with a sliver of a silver one. In another the house is drawn inside a geometric projection of a rectangle, which is itself inside a huge head, a block from which he carves his vision of the house, like in the childhood game of Chipaway. We have the drawings of the terrace extension, a Geometer’s plan for the work he went on to carry out. Art and life, his will imposed on the world; the terrace he built is now the centre of your experience of the house, its pleasure, where you survey the valley, the sky and the mountains all at once, and in the summer an inside-outside house.

Yellow is one of his favourite colours. Lemon yellow. It seems to flood his canvases. The reason must be metaphorical, because there is very little actual yellow in the valley that I can think of; a rash of autumn blooming crocus, a lemon tree that grudgingly bears a few lemons, but dry, discoloured nasty ones. Definitely not enough yellow to balance the greens in their many shades and densities throughout the year. Green dominates. Perhaps he chose yellow because it is a hopeful colour, a colour of resistance to the rule of green.

Das Haus Istvan Laurer ’83.

Below is – again – a rough translation of what he wrote next to one picture a year before he chiselled the slate on the front wall. He must have been in the manic phase of buying and occupying a new house to write this, the purchase of which empowered him to think differently.

The search for truth was louder both in terms of the pictorial form and the pictorial vocabulary. Those who prefer the more dramatic version may read this as: he lived through the crisis that no artist is spared.34

Which probably reads better in German. Is the search for truth a crisis? If so, what are the stakes? And why do artists have to undertake it?

More interesting to me is: what is the story of this house?

In a forgotten folder I find more drawings by Istvan, this time dreams for the house that never materialised. A loggia upstairs, with arches instead of windows open to the elements, also a short bridge from the main house to the derelict buildings behind, which were to be restored. This span creates the beginnings of an alleyway, a shared space between houses, the beginnings of a hamlet. I have seen smaller vicoli, just like this, intimate paths between homes, semi-enclosed by walkways overhead. Were these drawings part of his vision as an artist? His crisis was one of love (which presumably ran out), but also of time and money, of which he presumably never had enough.