Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

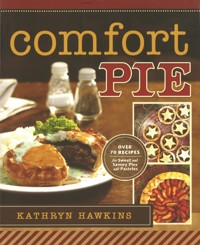

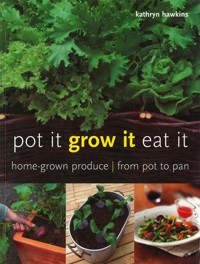

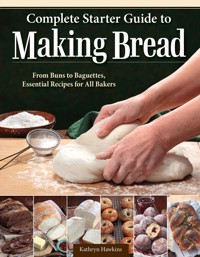

If you are a seasoned bread maker looking for tasty new bread recipes or baking techniques including how to bake bread in an air fryer or slow cooker or if you are new to breadmaking, The Complete Starter Guide to Making Bread is for you. With more than 35 years of experience as a recipe and food writer, author Kathryn Hawkins understands the importance of providing clear, concise, and easy-to-follow instructions for creating the perfect loaf of bread. Chapters include the history of bread and breadmaking, essential ingredients, and breadmaking techniques including kneading, proofing, knocking-back, shaping, baking, cooling, slicing, and storing. The 30 sweet and savory recipes include the classic white loaf, soda bread, cinnamon bread, whole wheat loaf, focaccia, cornbread, and a variety of gluten-free and vegan versions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 179

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© 2024 by Kathryn Hawkins and IMM Lifestyle Books, an imprint of Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

Portions of Complete Starter Guide to Making Bread (2024) are taken from Self-Sufficiency: Breadmaking (2016), published by IMM Lifestyle Books, an imprint of Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

Portions of Complete Starter Guide to Making Bread (2024) are taken from Amish Community Cookbook (2017), published by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Fox Chapel Publishing.

ISBN 978-1-5048-0144-7

eISBN 978-1-63741-416-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024940861

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112, send mail to 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552, or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Contents

Introduction

A Brief History of Bread and Making Bread

Essential Ingredients

Equipment

Basic Techniques

Troubleshooting

Recipes

Basic White Bread

Free-Form White Loaf

Whole Wheat Loaf

Poppy Seed Braid

Spelt Bloomer

Baguette

White Sourdough

French-Style Sourdough (Couronne)

Ciabatta

Rye Sourdough

Gluten-Free Sourdough

Gluten-Free Oaty Loaf

Focaccia

Steamed Sesame Buns

Bagels

Pita

Grissini

Naan

Brioche

Doughnuts

Chocolate Bread

Christmas Bread

Carrot and Cumin Loaf

Air Fryer Cheese and Onion Buns

A Very Slow Loaf

Soda Bread

Easy Cinnamon Bread

Cornbread

Banana Nut Bread

Corn Tortillas

Photo Credits

Bibliography

About the Author

Introduction

Making bread is truly fascinating. A food that contains a few very simple ingredients—flour, water, yeast, and salt—when given the correct conditions and care, work together to make something that most of us eat and enjoy every single day. Bread is one of life’s simple pleasures. Nothing beats a slice of freshly baked bread and butter or a freshly ripped crusty chunk dipped in olive oil.

The process of making bread dough can be regarded as therapeutic—there’s nothing better for relieving a bit of tension than thumping and kneading dough on a kitchen tabletop! Adapting a recipe by adding extra ingredients and shaping the dough to fit your requirements is creative. Filling your kitchen with the delicious smells of a fresh bake heightens the senses. And, of course, the finished product tastes great and is guaranteed to bring satisfaction. Bread is the staple food of many diets all over the world, and being able to make your own means you can provide tasty and nutritious loaves for yourself, your family, and your guests.

This book aims to provide anyone who wants to make their own bread a good grounding in all the essentials that go together to make the perfect loaf. You’ll find a guide through the ingredients, as well as a simple explanation of their role in making dough. This is followed by an in-depth look at the different stages involved in breadmaking. It might look a bit daunting at first glance, but it really is very straightforward once you get going. Just a few simple guidelines and you’ll be well on your way to creating your perfect loaf.

Once you’ve read through the basics, you’ll find the all-important recipe section. These pages should provide you with instructions for all the basic loaves you might want to cook, from a simple white loaf to more luxurious enriched breads. There are recipes for gluten-free baking as well as yeast-free loaves, and throughout this section, you’ll find hints and tips for making variations in flavor, texture, and shape. All recipes are or can be adapted to be vegan-friendly.

You don’t need any fancy equipment. Once you’ve got your ingredients organized, you should be able to get started right away. Soon, you’ll be enjoying the tempting aroma of your own loaves baking in the oven and the taste of delicious, healthy, freshly made bread. Happy baking!

An excellent loaf, like this Free-Form White Loaf, can be made with four basic ingredients: flour, yeast, water, and salt.

A Brief History of Bread and Making Bread

Bread is a familiar food recognized all over the world. It is sometimes referred to as “the staff of life” and provides vital sustenance from times of famine and hardship, when individuals often survive only on bread and water. It is also found in feasts and festivals when bread is an integral part of a celebratory meal.

In many cultures, bread plays a significant role and is often part of family traditions. Here, a family shares bread during Ramadan.

Bread has been a mainstay in culinary and cultural life since prehistoric times. It has been the center of religious customs and superstitions for centuries. For example, in some Christian traditions, the “breaking of bread” during the Holy Communion symbolizes the body of Christ; crosses on fruity spiced bread buns at Easter represent the crucifixion; loaves hung in houses on Good Friday ward off evil spirits; and loaves baked with a cross cut into the tops is a ritual to “let the Devil out.”

Other breads are baked for specific occasions: hot cross buns for Easter, matzo for Passover, and abundantly decorated loaves for Harvest Festival to signify fertility and abundance for the year ahead. The pan de muerto is made for Mexico’s Day of the Dead and is bread decorated with bread bones to symbolize the cycle of life from birth to death. After the breaking of the fast at Ramadan, iftar, bread is an important part of the meal that follows, representing sustenance and nourishment.

Baking bread during the Christmas season often served as a symbol of hope for good crops as well as good fortune for families in the upcoming new year. Sourdough bread is one of the popular types of bread to make during the holiday season.

Before specific tools were invented, flour was made by grinding and pounding grains and seeds, stone on stone.

With the invention of tools like as pestles and mortars, people were able to grind grains and seeds more easily and consistently.

The evolution of bread goes hand in hand with developments in crop raising, milling, and baking. Grain production is completely reliant on climate. In Europe, West Asia, and the Near East, thrive the grains that give bread its chewy texture, such as wheat, rye, and barley. Where the climate is less suitable, such as East Asia, other crops like rice have become the staple of choice.

Since humans started using tools two to three million years ago, they were able to grind grains and seeds to make a coarse flour by using a pestle-and-mortar-type utensil. These simple flours were mixed with water and cooked in the fire or on hot stones to make hard, flat breads. This “bread” was a common part of the diet in late Stone Age life in parts of the world where grain grew well. Today, this basic technique is still used in recipes like roti, chapati, and tortillas— all forms of this ancient cooking method.

As civilizations and machineries developed, this simplistic grinding process was superseded by two flat stones, referred to as “saddle stones,” pressing against each other to produce a finer grain dust. This method is represented in Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the stones themselves have been excavated in many parts of the world.

Tortillas are still made as they were in the Stone Age by mixing the flours in water and cooking it over a fire, such as over a stovetop, to create a flat bread.

Saddle stones were created in ancient civilizations to obtain a finer grain dust that was more ideal for breadmaking.

The ancient Egyptians are credited with leavening bread, although they probably discovered the process by accident. No doubt a batch of simple dough was left out in the open and became contaminated with wild yeasts in the air. In the warmth of the sun, the dough began to ferment and rise. When these newly created “yeasted” breads were baked, they were lighter in texture and were easier to eat than the usual flat baked loaves.

Alongside this baking creativity, Egyptians were wine and beer makers, so they knew how to use yeast in these processes. It was only a matter of time before they put the two processes together. Soon, the bakers discovered that a piece of this fermented dough could be added to a fresh batch of dough to make it rise. By 2,000 BCE, bread had become so popular in Egypt that there is evidence of a professional baking industry, producing leavened and traditional flat breads.

When the Israelites fled Egypt, they left behind the leavened bread they had been used to. After praying for food when they found themselves starving in the desert, their prayers were answered when they discovered tiny, sweet-tasting grains (probably lichens blown in on the desert wind). They were able to grind this plant material to make porridge and their own flat breads. And so, the origin of Passover unleavened bread, matzo, became a tradition.

Due to the popularity of bread in Ancient Egypt, Egyptians began commercially producing leavened and traditional flat breads, which was confirmed by Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Wheat wasn’t grown in Greece and the North Mediterranean until around 400 BCE. Until then, bread made from barley was the mainstay. Once wheat was embraced as part of the diet, the people from this region began making dough from partly refined wheat flour and whole grains. Soon they regarded these “white” loaves as superior and fit for the gods. They also added seeds, honey, fruit, and nuts to doughs and enriched their loaves with olive oil.

Koulouri Thessalonikis, Greek sesame bread rings, date back to the Byzantine Empire. Today, they are a common street food in Greece.

The spread of the Roman Empire saw the real development of breadmaking. The less-reliable, spontaneous fermentation processes of the Egyptians were phased out and replaced by a reliance on brewers’ yeast, a technique picked up from the Gauls, who added beer to their doughs. Bread in its many shapes and forms became a central feature in late-Roman culinary life, and a vast amount of wheat was imported from North Africa and beyond to keep up with the popularity. The Romans used teams of animals or enslaved people to operate massive geared grinding stones that produced flour on a much larger scale, and they also used sieves to remove the coarse outer layers, resulting in finer flour.

To produce large amounts of flour, the Romans used teams of animals to operate massive grinding stone wheels.

In Europe, by the Middle Ages, there was a thriving bakery trade with specialist bakers producing whole-grain traditional loaves as well as more-refined and luxurious white bread. Loaves were produced to suit all levels of society: “hall” bread for the property owners made from the finest milled grain; hulled bread, made from bran, for the servants; well-cooked, crusty whole wheat (known as wholemeal in the UK) loaves for cooking; and trenchers, which were thick, dense, flat breads used as a plate during medieval feasts—after the platter contents had been consumed, the leftover trencher was soaked by the juices from the meal and was either eaten at the table or given away to the poor.

Maize was the staple grain known to Native Americans, so they used it to make flat breads. They often used a metate, a Mesoamerican flat mortar, to grind the corn into a flour.

Fancy breads and pastries became popular during the Renaissance period, and domestic recipes began to appear in cookbooks of the time. During the eighteenth century, agricultural systems further evolved. Cereals could be more refined and ground, and the introduction of silk sieves produced a finer, powdery form of flour. Bakers were able to use brewers’ and distillers’ yeasts as ingredients, adding them directly to bread mixtures rather than the traditional method of adding a piece of fermented dough to achieve a rise.

In America, Native Americans were making flat breads from corn, also known as maize. This was the only grain available to them until early settlers arrived from Europe and brought with them wheat and rye, which thrived.

The origin of tandoor bread, bread made in a traditional clay oven, is unknown. But it dates back 5,000 years during the Indus Valley Civilization, located in the region we know today as South Asia.

The newcomers found that their flours combined well with cornmeal to make different types of loaves. Influxes of various European immigrants helped increase the variety of baked goods as each settler brought with them their own country’s recipes. Scandinavians used rye flour to make limpa, a yeast-leavened spice loaf, while the Germans used rye to make rich, dark pumpernickel bread. Italians from Naples introduced the bread-based pizza, and the Dutch, doughnuts and waffles. The prospectors and explorers who arrived in the West in the nineteenth century brought with them their sourdough techniques, and today sourdough bread is synonymous with San Francisco.

As civilizations evolved, water then wind was harnessed to turn the stones in purpose-built mills. In modern industrial times, purpose-built mills like windmills were constructed to grind wheat for flour.

Wheat has been growing in northern China for a long time but was mainly eaten by the more affluent in society. Most of the population ate millet and barley among other grains. In this part of the world, the baking oven was not known, and so bread and similar foods were steamed. In Japan, rice was the crop of choice and was simply eaten as a grain. However, after a succession of famines in the nineteenth century, bakers became more interested in making bread; although it was drier, sweeter, and more cake-like than more familiar Western breads.

In India, wheat was common in the north but was expensive, so various grains and other cereals were used to make flours for baking. Clay ovens, called tandoors, have been used to make crisp, chewy, and bubbly naan bread for many years, but most flat breads from this part of Asia are cooked on simple flat stones and griddle-type flat plates.

The Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe and North America brought with it huge social changes. Work took people outside their own homes and personal incomes increased. People left rural areas and moved to towns and cities, and to meet demand, the bakery business expanded and became mechanized on a large scale. In the 1870s, steel roller mills arrived, and white flour was able to be produced on a huge scale and old coal ovens were replaced with more efficient gas ovens, which helped speed up the baking process.

By the twentieth century, advances in the breadmaking process were evolving more rapidly. Flour was bleached, seemingly to make it more appealing, and the requirement to enrich flour with calcium, iron, and vitamins was introduced. After the second World War, once rationing was over, the consumption of foods high in fat and sugar rose in popularity, and baking bread became a factory operation.

The most notable development happened in 1961, when the Chorleywood bread process (CBP) was launched. This sped up the whole industry by developing a factory procedure that was able to use lower-grade wheat, more yeast, and more chemical ingredients in combination with rapid fermentation and high-speed mechanized dough mixing. CBP was adopted by many countries around the world; the resulting bread was softer and less crusty and was easily available and affordable. This mass-produced bread was easy to eat and provided easy sustenance for people on the move. In the home, the bread lasted several days and provided a cheap filler to bulk out more-expensive foods like meat, fish, and dairy products. As more and more women went out to work, they had less time to make their own loaves, and most people became reliant on commercially produced bread.

With advancements in technology during the twentieth century, mills were able to speed up the breadmaking process by using industrial grinders to make flour.

Just a few decades later, a resurgence in baking would begin again. Once we all became more concerned about what we were eating in relation to our health, there was a drive to reduce fat, sugar, and salt in our diet. Consumers began to demand better flavor, texture, and quality from their daily bread. Concern about the use of pesticides in wheat production, and artificial additives used during commerical breadmaking, prompted a return to more-traditional types of flour as well as a rise in the production of organic cereals. Advances in medical research helped diagnose Celiac (Coeliac) disease, which is an individual’s intolerance to wheat and gluten. Manufacturers began to change the way they produced bread, and more organic, less-refined, and gluten-free loaves appeared on the shelves at local bakeries and grocery stores.

The development of the Chorleywood bread process (CBP) in 1961 resulted in mass-produced bread that was softer, easier to eat, affordable, and lasted several days at room temperature.

In the 1980s, a domestic mechanical bread machine was invented in Japan, and in a small way, this too contributed to the way we looked at our daily loaf. Soon, many homes embraced this appliance, which not only made and proved the dough from scratch, but also baked it as well. We were back to baking daily loaves, but in only a fraction of the time than making it by hand.

In recent years, artisan bakeries have sprung up, and more bakers are making bread to traditional recipes again. With the rise in popularity of farmers markets and specialist shops, bread has become more and more exotic and flavorsome. As is often the way, this sparks off an interest in the domestic setting, and once again, cooks have begun making their own bread from scratch.

While cooking was seen as a necessary evil a few years ago, taking up valuable leisure time and entertainment outside the home, in times of austerity and stress, home baking has become something that many of us enjoy. Never was this more apparent than during the worldwide pandemic in 2020. More and more of us spent time in our kitchens during lockdown, experimenting with recipes that we didn’t usually have time to make. The rise in veganism across the world and increase in environmental concerns have also helped increase the interest in making bread from scratch. Many bread recipes are naturally vegan, and those that aren’t can usually be adapted to become vegan-friendly.

Breadmaking has become so popular now that it has developed its own personality across all forms of social media with individuals sharing images, techniques, and recipes of their prized loaves. On television, shows based around baking challenges are fascinating audiences all over the world. There can be no doubt that we are enjoying baking bread more than ever before, and we are creating all sorts of delicious variations using the wealth of ingredients we have available to us today.

Household appliance companies have created easy-to-use and time-efficient bread maker machines for those who wish to make homemade bread.

Essential Ingredients

The archetypal loaf is made from flour, water, yeast, and a little seasoning. The type of flour you use along with other variations in ingredients will affect the outcome of your bread. The following pages offer a comprehensive guide to the different types of flour, leavening agents, and liquids you can use, as well as other ingredients that can be added to enrich, flavor, and give texture to your bakes.

Yeast is the most commonly used leavening agent for making bread. Its three standard forms are shown here: fresh, active dry, and instant dry.

To reduce the risks to the health of the wheat crops and the surrounding environment, sustainable farming methods have been encouraged, such as less reliance on artificial fertilizers to raise production levels.

Wheat

Today, wheat is one of the most important crops grown globally and is a vital ingredient for most breads and bakery items. To many of us, seeing fields of uniform wheat stems swaying gently in the breeze is a familiar and comforting sight. Over the past 200 years or so, farming has changed dramatically as demand for wheat has increased. More land has been taken over for raising crops, soil is fertilized before sowing to encourage growth, and crops are sprayed with pesticides and herbicides to prevent pests and diseases as well as to restrict weed growth. These practices, over time, cause a lack of biodiversity in soil and carbon escape when the soil is tilled, and this leads to an overall negative impact on the surrounding environment, wildlife, and human health.

However, new practices are being developed and adopted all the time to help reduce the risks to the environment and health. More sustainable methods are being encouraged, and subsequently, crops will benefit from growing in a healthier, more-natural ecosystem and environment—one that is not reliant on artificial fertilizers and other controls to raise production levels.

Before the invention of the combine harvester, wheat grass was cut by hand with simple farming hand tools, such as a sickle.