Contemporary Catholic Poetry E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Paraclete Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

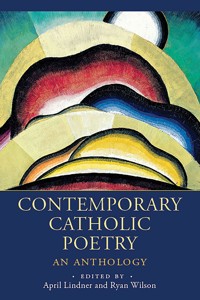

2024 Foreword INDIES Book of the Year FINALIST "...wonder shows up in these poets' work again and again." - America Magazine A Landmark Anthology of Contemporary Catholic Poetry A treasury of vibrant beauty and thought-provoking verse, this anthology is an essential addition to the library of any poetry lover or anyone seeking to explore the intersection of faith and art. This path-breaking collection brings together the work of 23 notable Catholic poets born after 1950, including Julia Alvarez, Carolyn Forché, Timothy Murphy, and Franz Wright. Edited by Ryan Wilson and April Lindner, this anthology celebrates the depth and diversity of the Catholic imagination, highlighting "the myriad ways the Church has left its mark on the imaginations of these notable contemporary poets." From personal reflections to explorations of faith, nature, life, and lament, these poems span a wide range of themes, styles, and forms, offering readers a rich tapestry of spiritual and creative expression. Whether capturing moments of beauty, wrestling with doubt, or addressing the complexities of modern life, this collection reveals the enduring influence of the Church on the poetic tradition. "Above all, poems remember. Each poem is, on a fundamental level, an act of remembrance, a kind of handprint pressed against the wall of Time."—from the Preface of Contemporary Catholic Poetry

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FORContemporary Catholic Poetry

The best thing about this carefully curated collection is that the poems gathered herein are anything but pious hymns and odes; rather, they address the concrete particularity of the everyday and the mystery of grace in a broken but beautiful creation. That’s what makes them Catholic: the faith that inhabits these poems isn’t sprinkled on top; it glows from within and illuminates the world around us.

—GREGORY WOLFE, Publisher, Slant Books, Author of Beauty Will Save the World

Bravo! This is a remarkable introduction not only to contemporary Catholic poetry, but to poetry in general. The poems are carefully chosen, consistently powerful, and truly catholic in their range. The introductions are engaging and useful. Rare is the book that’s ideal as either a gift or a textbook. This one is.

—MIKE AQUILINA, Chairman of the Board, International Poetry Forum, and Author of Rhymes’ Reasons

What an extraordinary collection of poets has been brought together here by April Lindner and Ryan Wilson in this profoundly moving panoply of twenty-three American voices covering the past seven decades, each in their way paying homage to the deep spiritual and existential concerns that haunt us all. Read it, friends, page by page by page, soak it all up and take in the music and pathos and beauty of what real poetry has to offer us.

—PAUL MARIANI, Author of Deaths and Transfigurations, The Mystery of It All, and All That Will be New

This is the definitive anthology of contemporary Catholic poetry in America and an important contribution to American letters more broadly. While deserving celebration among Catholic readers, the poets represented here merit much broader recognition. The wonderful poems in this anthology will delight, challenge, and move anyone interested in poetry.

—LEE OSER, Professor of English, College of the Holy Cross; Immediate Past President, Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers

Selective, startling, judiciously arranged—Contemporary Catholic Poetry is quite simply a gift to lovers of poetry, whatever their religious beliefs.

—MICAH MATTIX, Poetry Editor, First Things, Professor of English, Regent University, Co-editor, Christian Poetry in America Since 1940

This anthology should be a standard assignment in every Catholic school in the English-speaking world. From Julia Alvarez and Dana Gioia to James Matthew Wilson and David Yezzi, we have the most superb verse by poets eager to speak of human affairs through a Catholic lens that takes in the full range of despair, doubt, joy, love, uncertainty, death, and faith. “I conjure the perfect Easter,” one of them writes; “I am the Angel with the Broken Wing,” says another; and “Nightly angst, ennui, and gloom / Refine the human need for some perfection,” says still another. These are thoughts given in eloquent words that young Catholics should ingest throughout their high school career. So, let’s go, diocese superintendents: you now have a tool to make English a thoroughly Catholic experience. Use it.

—MARK BAUERLEIN, Senior Editor, First Things; Author of The Dumbest Generation Grows Up

If the words “contemporary” and “Catholic” anywhere in proximity to the word “poetry” raise your eyebrows in alarm at fears of low artistic merit or dubious faith, April Lindner and Ryan Wilson’s anthology Contemporary Catholic Poetry will challenge these assumptions in unexpected ways. With its wide array of prolific and award-winning poets and its expert preface tracing the development and flourishing of Catholic poetry in Europe and America, this collection will be one that teachers, editors, poets and poetry lovers alike can return to time and again to be fed by mastery of form, image and narrative and be strengthened with hope in an unbroken continuum for the Catholic Intellectual Tradition.

—MARY ANN B. MILLER, Founding Editor, Presence: A Journal of Catholic Poetry; Professor of English, Caldwell University

For Mike Aquilina, Brad Leithauser, and Ernest Suarez, wonderful friends.

—RYAN WILSON

In memory of my grandmother, Virginia Andros.

—APRIL LINDNER

2024 First Printing

Contemporary Catholic Poetry

Copyright © 2024 by Paraclete Press, Inc.

Hard cover: ISBN 978-1-64060-970-9

Paperback: ISBN 978-1-64060-646-3

The Iron Pen name and logo are trademarks of Paraclete Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lindner, April, editor. | Wilson, Ryan, 1982- editor.

Title: Contemporary Catholic poetry : an anthology / edited by April Lindner and Ryan Wilson.

Description: First printing. | Brewster, Massachusetts : Paraclete Press, 2024. | Summary: “A compilation of recent poetry that is appealing both to Catholic readers and to the general reading public”--Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023058159 (print) | LCCN 2023058160 (ebook) | ISBN 9781640609709 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781640606463 (paperback) | ISBN 9781640606487 (pdf) | ISBN 9781640606470 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: American poetry--Catholic authors. | BISAC: POETRY / Subjects & Themes / Inspirational & Religious | POETRY / American / General

Classification: LCC PS591.C3 C66 2024 (print) | LCC PS591.C3 (ebook) | DDC 811.6--dc23/eng/20240221

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023058159

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023058160

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete Press

Brewster, Massachusetts

www.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

WELCOME, ALL WONDERS: A PREFACE

NOTES ON THE TEXT

EDITORIAL NOTES

Julia Alvarez (1950)

How I Learned to Sweep

Folding My Clothes

Spic

Bilingual Sestina

Ned Balbo (1959)

Son of Frankenstein

Miraculous Spirals

Hart Island

Molly McCully Brown (1991)

The Central Virginia Training Center

Labor

Prayer for the Wretched Among Us

The Convulsions Choir

Maryann Corbett (1950)

Northeast Digs Out from Record Snowfall

Airheads

Historic District, Walking Garden Tour

Defending Veronese

Prophesying to the Breath

Staging Directions

Sarah Cortez (1969)

Lingo

Tu Negrito

A Certain Kind of Case

Rosie Working Plain Clothes

Kate Daniels (1953)

The Playhouse

Dogtown, 1957

Getting Clean

Niobe of the Painting

Reading a Biography of Thomas Jefferson in the Months of My Son’s Recovery

Late Apology to Doris Haskins

War Photograph

Prayer to the Muse of Ordinary Life

Carolyn Forché (1950)

The Morning Baking

Expatriate

Selective Service

The Colonel

For the Stranger

John Foy (1960)

Eucalyptus Trees

Cost

Techne’s Clearinghouse

Dog

Sorrow, Meister Eckhart Said

Dana Gioia (1950)

The Next Poem

Interrogations at Noon

The Angel with the Broken Wing

Pentecost

Planting a Sequoia

Counting the Children

Summer Storm

Marriage of Many Years

Marie Howe (1950)

The Star Market

The Snow Storm

The Boy

What the Living Do

My Mother’s Body

What We Would Give Up

Easter

Prayer

Brigit Pegeen Kelly (1951–2016)

Petition

The Visitation

The Garden of the Trumpet Tree

Song

The Satyr’s Heart

April Lindner (1962)

Learning to Float

St. Theresa in Ecstasy

Our Lady of Perpetual Help

Fontanel

Carried Away

The Trip to Brooklyn Misremembered as a Roller Coaster Ride

Orlando Ricardo Menes (1958)

Miami, South Kendall, 1969

Sharing a Meal with the Cuban Ex-Political Prisoners

The Maximum Leader Addresses His Island Nation

Den of the Lioness

Palma y Jagüey

Wreath of Desert Lilies

Castizo

Juancito’s Wake

Timothy Murphy (1951–2018)

The Track of a Storm

Case Notes

Hunting Time

The Blind

Jasper Lake

The Reversion

Cross-Lashed

Soul of the North

Alfred Nicol (1956)

Elegy for Everyone

A Wage-Earner’s Lament

The Gift

Why Bees Hum

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell (1960)

Other Mothers

Now & At the Hour of Our Death

Watching Dirty Dancing with My Mother

Saint Sinatra

Sunrise in Sicily

Kiki Petrosino (1979)

Young

The Shop at Monticello

Souvenir

Twenty-One

Let Me Tell You People Something

Witch Wife

Benjamin Alire Sáenz (1954)

To the Desert

Journeys

Creation

Avenida Juárez. May 7, 2010. 12:37 A.M.

Daniel Tobin (1958)

The Afterlife

Chin Music

Where Late the Sweet Birds

An Echo on the Narrows

Homage to Bosch

Aftermath

James Matthew Wilson (1975)

See

“Madre de Gracia”

On a Palm

A Prayer for Livia Grace

March 25, 2020

April 15, 2020

Ryan Wilson (1982)

For a Dog

Disobedience

Face It

Philoctetes, Long Afterward

Heorot

In the Harvest Season

Franz Wright (1953–2015)

Year One

Transfusion

Memoir

Baudelaire

Letter

P.S.

Crumpled-Up Note Blowing Away

David Yezzi (1966)

Crane

Tyger, Tyger

The Chain

The Good News

Free Period

Minding Rites

Weeds

Mother Carey’s Hen

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE EDITORS

WELCOME, ALL WONDERS: A PREFACE

Welcome, all wonders in one sight!

Eternity shut in a span,

Summer in winter, day in night,

Heaven in earth, and God in man.

Great little one! whose all-embracing birth

Lifts earth to Heav’n, stoops Heav’n to earth.

—Richard Crashaw

WHAT DO POEMS DO?

Amid the global pandemic and many upheavals of 2020, news broke about a team of archaeologists, led by a professor from Exeter University, who had discovered, deep in the Amazon rainforest of southern Colombia, an eight-mile-long wall of stone covered in artwork from more than 12,000 years ago. Among the tens of thousands of paintings are depictions of long-extinct Ice Age flora and fauna, such as the mastodon, and of masked human figures dancing, hand-in-hand, likely in some holy ritual forgotten eons ago. Many more of the paintings are simply images of a human being’s hand: innumerable human hands from 10,000 years before the birth of Christ, from roughly 9,000 years before the siege of Troy represented in Homer’s Iliad. Those humans who pressed their muddy hands against a stone wall so long ago are nameless now. Their entire civilization remains a mystery to us. And yet, their handprints, elaborate geometric designs, and exquisite paintings reveal to us glimmers from a lost world, each image speaking in a dazzling silence for its maker, illuminating our imaginations with the tacit assertion, “I was here.”

In addition to its astonishing size, the wall has another remarkable feature: some of the paintings are at such a great elevation that they cannot even be viewed from the ground. How did anyone get up that high, that long ago? Why were these paintings made? Why climb to such perilous heights to leave a handprint? No doubt, archaeologists and art historians and all sorts of scholars will be studying this magnificent monument for centuries to come, and we shall be learning more and more about a vanished civilization.

Among innumerable other questions raised by such a miraculous archeological discovery is this one: why do humans take such pains to make art? Ultimately, such questions lead us deep down into that darkling realm where we must consider what it is to be a human being. For our present purposes, however, we might begin by delimiting the question: why do contemporary human beings make poems, and why should contemporary humans read poems? For more than two thousand years, questions of what poetry is, how it works and ought to work, why it’s written, and why it should be read have nettled poets, readers, scholars, and critics. Before we address the role of poetry for people today, we should first consider yet another question: what do poems do?

Poems represent the world and the people who inhabit it: they introduce us to plants, animals, human characters, and highly specific places. They show us striking images that may be familiar to us or entirely eldritch, tell us about experiences that might be akin to our own or quite different from our own. They delight us, seduce us, inspire us, instruct us, mock us, condemn us, console us, and mourn us. They challenge us, protest against us, and, sometimes, they baffle us. They celebrate the glories of the created world and its people, and they commemorate momentous occasions; they also curse the cruelty and the horror of the world and its people, and they lament catastrophes. They imagine other people’s lives and other worlds. They invoke deities and absences. They also speak intimately of heartfelt truths, describe local haunts, and address ordinary people directly. They meditate on living, on dying, and on the passage of time. They tell us stories, they tell us lies, and they tell us stories that reveal the truth through lying, to paraphrase the great painter Pablo Picasso. They enchant us with beauty and appall us with terror. Above all, poems remember. Each poem is, on a fundamental level, an act of remembrance, a kind of handprint pressed against the wall of Time.

With this in mind, we may shift to ancient Rome to consider our question about what poems do. The Romans of antiquity used a single word for the poet and for the prophet: vates. What do the poet and the prophet have in common? If we follow St. Thomas Aquinas in thinking of prophecy as that which reminds us of what we have known but have forgotten, perhaps the linking of the poet and the prophet will not seem so outrageous. Hundreds, if not thousands, of the world’s best-loved poems belong to the memento mori tradition, the “remembrance of death” tradition. Why? This is so because we are always forgetting our own mortality. Drive down any interstate through any major city, and you’re likely to encounter any number of drivers speeding, fiddling with phones, weaving in and out of lanes, and generally demonstrating that they are not particularly aware of their own mortality or of the mortality of others. Then again, many more of the world’s best-loved poems belong to the carpe diem tradition, or “seize the day” tradition, dating back, at least, to the Roman poet Horace’s Ode i.11, published in 23 bc, the source of that famous Latin tag. Why? Not only are we always forgetting our mortality, but we’re also always being distracted from our purposes, drifting into procrastination, frittering our time away with unimportant concerns, watching silly YouTube videos, and so forth. Abstractly, we all know that we will perish and that we must make the most of our time on earth; however, in an immediate sense we are always forgetting this knowledge. We too frequently lack the spiritual discipline to keep these basic truths before the mind’s eye. Consequently, a great many poems have reminded us, and continue to remind us, of these truths which we know but are always forgetting.

Because the human being is so forgetful, the memorization and recitation of poems have long been valued for their cultural functions. For instance, consider the oral Sumerian traditions passing along the Gilgamesh before it was written; consider the function of the Sutras, or of Homer’s great catalogues; consider the rhapsodes we meet in Plato, or the Old Norse skalds and Anglo-Saxon scops passing along the Beowulf. Consider the vibrant and often violent world of the Tang dynasty as recorded by Tu Fu, or the extraordinary delicacies preserved in Bashō’s haiku, or the rubicund and puckish realm of Chaucer’s England. Times change, and the cultures of specific places change along with them, but poets seem always to be fending off forgetfulness. In all these poets, in fact, a version of meter, or measurement, has been retained to help us remember. Of course, what a given culture is in danger of forgetting shifts, and poets must shift accordingly, but poets are always reminding individuals of their era, and most especially reminding themselves, of those truths in danger of being forgotten, and poets are always attempting to give these reminders memorable form, enchanting form.

One of the things human beings are always forgetting is that the world is greater than any individual’s idea of it. The world is more complex, more manifold, more mysterious than any mortal mind can fully comprehend, as is the human individual. And yet, in our desire for power and for comfort, we often forget this wildness, this elusiveness, this uncapturable quality. I am reminded, as readers familiar with the Buddhist tradition might be, of the “Diamond Sutra,” in which the Buddha guides Subhuti toward a transcendence of his limited vision of reality. I’m also reminded of Euripides’s great play The Bacchae, in which King Pentheus over and again tries to imprison the wild god Dionysus; of course, no prison can hold that fertility god from the East, and ultimately Pentheus is ripped limb from limb by the Bacchae (as a fertility god would traditionally be ripped limb from limb) in a paradoxical reversal, or peripeteia. In short, we deny the wildness of the world at our own peril. As Henry David Thoreau once wrote, “I’ve never met a man who was fully awake.” Indeed, we drift into a kind of sleep, go about in a sort of somnolence, unaware of the cosmic drama unfolding around us and equally unaware of the spiritual drama stalking the boards and chewing the scenery within each of us. In this world of superabundant variety and bright vitality and fluorescing flux, we find ourselves, of all things, bored, for we forget the superabundant variety and vitality and flux and replace that reality in our minds with an illusory image of the world as a familiar and fully determined thing. We are, in fact, bored not with the world, but with our image of it, a reductive image which becomes commonplace.

What is too easily beheld is hardly seen. The fragile blossoms of our thoughts and words float upon a dark and fathomless river, yet we mistake the blossoms we can hold for the river we cannot. We become, in short, superstitious. The vocation of the poet, the calling of the poet, is perhaps first a call to awaken, a call to seek out that wildness, that strangeness of being which we can encounter only when we escape the prison of our own ready conceptions, when we slip through the bars of our customary habits of mind. And one of the most important reasons contemporary humans write poems is to make contact with that world outside the jailhouse of the rote routine, to reach out toward those wonders we have suspected, have sensed, maybe even have known, but cannot hold, cannot continually remember, those rare and miraculous moments of revelation.

So, having reflected on what poems do, we might now ask: why should any contemporary human read poems? The successful poem, like the successful magic trick, is a revelation more about the audience than about the artist. As the great theologian Jacques Maritain points out, all human beings possess the “poetic faculty”—the desire to make something beautiful—however, for various reasons, few human beings pursue the “poetic art.” Ideally, poems articulate insights available to all human beings, guiding the audience toward new vistas, new vantage points from which we can discover truths new to us, see afresh old and familiar truths, and glimpse the promises of eternity from our foothold in the temporal.

In fact, the great Roman poet Horace, who was Poet Laureate during Rome’s aetas aurea, or “golden age,” tells us in his epistolary Ars Poetica that the aims of poetry are aut prodesse…aut delectare, “to delight or to instruct.” As it happens, the best poems both delight and instruct us in some way. The successful poem must somehow interest us, charm us, draw us in, cast a spell on us before it can lead us toward any discovery. Poems want to give us language with which to express and understand ourselves.

If a poem can delight you in the way a painting you love delights you, if a poem can enchant you, it entices you to pay attention to it, and to yourself, in a way that we’re unaccustomed to doing. It asks you to stop, to put aside your busy schedule and your daily routine, and to linger, to relish the delectable savor of it, and to think about why it’s so delicious to you. “Wow,” you might say, “I like this. But why do I like it so much?” In the case of a painting, your eyes may devour the lines or the colors, or a striking figure. In the case of a poem, you may roll lines around on your tongue like a dollop of honey, or you may, like Emily Dickinson, feel as if the top of your head had flown off in a moment of wild discovery. But only when you are enchanted, only when you are enraptured by the flavor of the work will you be inclined to pause, and to consider what has so enraptured you, and why—what is it in you that responds so powerfully to such a thing?

Far too often, contemporary Americans come to think they don’t like poetry because they are erroneously led to believe that poetry is about ideas. It is not. There are ideas in poems, usually, and there are emotions, but of foremost importance is the relish of poems, the sudden, immediate “yes” that the right words can conjure. What’s more, every good poem ever written was written, in a sense, for you: good poets don’t write to be obscure, or difficult, or to run up footnotes like a score in some video game. No, good poets don’t write to torture high school students and college students of the future. They write with the hope of bringing readers of their time, and of the future, delight, and perhaps a bit of instruction, too. Behind most good poems is a sound love of the world, of its things and peoples and places. Poems ask you, too, to pay attention to what was so loved as to be rendered lovingly for you, for all created things pass away. Imagine if some talented artisan made an exquisite crystal chandelier for you; that’s something like a poem. It has its use: it can illuminate. However, a crystal chandelier is not one of those hideous fluorescent lights that are acquired cheaply; rather, it’s a kind of illumination that is a gift, a beautiful gift whose function and beauty are inseparable. While all sorts of subtle patterns and meanings might be wrought into such a fancy chandelier, probably you’d rejoice just to have a beautiful light-source in your house. Just so, poets would like you to admire their craftsmanship, and to study their intricacies, but most of all they want to give you an illuminating gift. That gift is a token of remembrance.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CATHOLIC POETRY IN ENGLAND AND EUROPE

To place this collection in context, we should consider its poetic ancestry, as it were. The earliest English poem extant, “Cædmon’s Hymn,” composed miraculously by a cowherd working for the monastery at Whitby, comes down to us via the ad 731 book Ecclesiastical History of the English People by the Venerable Bede, a Catholic monk. Monasteries played important roles in other Old English masterpieces such as “The Dream of the Rood” and the Beowulf. Despite his lampooning corruption within the Church, the first great English-language poet whose name we know, Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1340s–1400), was Catholic, as was the visionary Margery Kempe (1373–1438?). The roots of English language poetry reach deep into the rich soil of the Faith.

The Catholic Church and England had a long, if at times uneasy, alliance. Under King Henry VIII and his Tudor successors, Catholics found England to be increasingly hostile. When King Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn in January of 1533, banishing his wife Catherine of Aragon to Kimbolton Castle, he set into motion his own provisional excommunication. As Caesar said, upon crossing the Rubicon, Alea iacta est, “The die is cast.” In 1534, King Henry declared himself, via Parliament’s passage of the Oath of Supremacy, the head of the new Church of England, institutionalizing a separation from Rome while also demanding that his subjects swear an oath of loyalty to his new church. Those who refused the oath faced imprisonment and execution. The fate of Catholicism in England and the fate of Catholic literature in the English language were altered forever, formed by the need to flourish in a hostile environment.

Under the reign of Henry’s successors, religious divisions in England grew deeper still, a river of blood coursing through them. Elizabeth I went so far as to decree that being or harboring a Catholic priest in England was a crime punishable by death. Following years of torture, St. Robert Southwell, a Jesuit priest and author of the much-celebrated poem “The Burning Babe,” suffered terribly for the crime of being a Catholic priest on English soil. In 1595 he was “drawn to Tyburn upon a hurdle, there to be hanged and cut down alive; his bowels to be burned before his face; his head to be stricken off; his body to be quartered and disposed at her majesty’s pleasure.”

Given the tyranny of the time, Catholicism in England withdrew into the shadows, Catholic writers being forced either to hide or renounce their faith. Raised a Catholic and taught by Jesuits, John Donne renounced Catholicism and published Ignatius His Conclave in 1611, a skewering satire against St. Ignatius Loyola and the Jesuits. Shakespeare, who was raised by Catholics and whose father had taken a vow of fidelity to the Catholic Church, seems to have kept private his adult religious loyalties, though saints appear frequently in his writing and the Catholic doctrine of Purgatory is of significance to his masterpiece Hamlet. Ben Jonson converted to Catholicism while imprisoned in 1598 and returned to the Church of England only when even more stringent anti-Catholic laws compelled him to do so in 1610. Alexander Pope, generally thought the greatest English-language poet of the eighteenth century, was a Catholic. But between Pope and the nineteenth-century Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins, no major Catholic poets are to be found in the English language. Certainly, the dearth of Catholic poets during this time may be attributed in large part to the tyrannical anti-Catholic laws in England, which caused many Catholics to flee England and resettle in more hospitable countries on the European continent.

THE FLOURISHING OF EUROPEAN CATHOLIC POETRY

Catholic poetry on the continent fared quite differently. During Elizabeth’s reign in England, Spain experienced its literary Golden Age, highlighted by Catholic poets such as Fray Luis de León, St. Juan de la Cruz, Luis de Góngora, and Lope de Vega, the “Spanish Shakespeare” and inventor of the three-act tragedy. Around the same time, French poetry flourished with the literary movement La Pléiade, featuring Catholic poets such as Joachim du Bellay and Pierre de Ronsard. Catholic dramatists such as Molière and Racine dominated the seventeenth-century stage. In the nineteenth century, Catholic poets Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud stood at the forefront of French letters.

It was not only these French writers who paved the way for Catholicism’s return to prominence in English letters. In 1829 the Roman Catholic Relief Act repealed many of the oppressive anti-Catholic laws in England, making it much less unpleasant for Catholics to live there. The High Church Anglicanism of the Oxford Movement in the 1830s and 1840s sought to restore some Catholic traditions to the Church of England, and St. John Henry Newman’s powerful and public conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1845 broke significant ground.

Meanwhile John Ruskin’s influential writings and lectures at Oxford helped to bring about the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group deeply influenced by Catholic Italian poets and artists of the Middle Ages, especially Dante Alighieri and his circle. In The Renaissance (1873), Walter Pater explored his devotion to beauty—especially the beauty of works by Catholic artists like Botticelli, Luca della Robbia, and Michelangelo. This devotion also opened a passageway for spiritual exploration, as chronicled in Pater’s masterful novel, Marius the Epicurean (1885). In the novel, the protagonist Marius is drawn to the mysteries and rites of the early Catholic Church by their beauty. Combined with the relaxing of anti-Catholic laws, the cult of beauty blazed the trail by which writers of the Decadent generation would wend their way to Rome.

Across the Atlantic, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow also broke ground on behalf of Catholicism. From its inception, the United States harbored strong anti-Catholic biases that influenced the work of most major nineteenth-century writers. Despite such biases, Longfellow’s cosmopolitanism and polyglotism led him to study deeply the languages and literatures of traditionally Catholic nations such as France, Spain, and Italy. His knowledge of other cultures also led him to believe that “Every human heart is human,” as he wrote in his 1855 epic The Song of Hiawatha. As Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard, Longfellow went so far as to found The Dante Club, and even published the first American translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. He had written powerfully against slavery and against the United States’ horrific and dehumanizing treatment of Native Americans: in translating Dante’s masterpiece in the 1860s, he implicitly took a stand against America’s long-standing anti-Catholic sentiments. What’s more, Longfellow initiated a grand tradition of Dante scholars at Harvard, including Charles Eliot Norton, the Spanish philosopher George Santayana, and T. S. Eliot, whose lifelong devotion to Dante shaped Modern literature and opened the way for Catholic literature to thrive in mid-twentieth-century America.

As it happens, the so-called “Catholic Moment” in American literature would begin in London, England, where a young T. S. Eliot, abroad and working on his doctoral thesis in philosophy, would meet Ezra Pound. Both Pound and Eliot would go on to pursue projects deeply influenced by Dante, that greatest of all Catholic poets. Pound and Eliot promoted a vision of the literary work as a whole which is more than the sum of its parts. They believed that every part in a work must partake in a pattern that gives increased resonance to each constituent part. The resonating parts then give greater resonance to the whole. No line or passage has its meaning alone, no matter how beautiful. In a masterwork of literature, all parts, and all patterns, must work together, as they do in the towering cathedral of genius that is Dante’s Divine Comedy.

THE CATHOLIC MOMENT IN AMERICAN LITERATURE

Oddly enough, this Dantesque conception of literature—adumbrated in ancient lyric poets like Sappho, Catullus, and Horace, and in the great epics—resides at the core of what contemporaries generally call “The New Criticism.” This term is a kind of phantasm, conjured by a long-standing misreading of the preface to Understanding Poetry by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren. Contrary to common belief, the so-called New Critics did not advocate ending literary study with the text itself; they advocated beginning literary study there. New Critics such as Eliot, John Crowe Ransom, and Ransom’s students Brooks, Warren, and Allen Tate promoted a vision of the poem as a work whose parts should all partake in patterns and whose parts and patterns should all work in harmony. That is, the New Criticism was thoroughly Dantesque. Indeed, Allen Tate and his wife, the novelist Caroline Gordon, both converted to Catholicism. The generation of writers who grew up reading Brooks and Warren’s textbooks not infrequently converted to Catholicism. And a number of cradle Catholics found this prevailing Dantesque aesthetic conducive to their own writing.

The result was the Catholic Moment in American literature. Between 1944 and 1969, Catholic writers received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for poetry and fiction nine times. Twice was a Catholic named Poet Laureate of the United States (then called the “Consultant to the Library of Congress”). A host of Catholic writers enjoyed renown in this period: Daniel and Ted Berrigan, John Berryman, Robert Fitzgerald, Isabella Gardner, Julien Green, Josephine Jacobsen, Jack Kerouac, Robert Lowell, Phyllis McGinley, Claude McKay, Thomas Merton, John Frederick Nims, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Katherine Anne Porter, J. F. Powers, Kenneth Rexroth, Allen Tate, Hisaye Yamamoto, and many more.

But for more than a half-century-since 1969-no practicing Catholic has served as US Poet Laureate. Only a handful of Catholic writers have won the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award. Many esteemed contemporary writers were raised as Catholics, are “cultural Catholics,” or bear some influence from Catholicism; nonetheless, that brief Catholic Moment, during which the American public treated the theology of the Catholic Church respectfully, can seem like ancient history.

THE SACRAMENTAL VISION OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CATHOLIC POETRY