Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

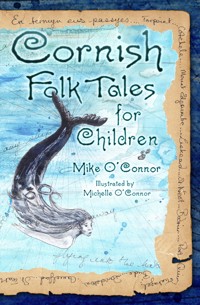

Join Jamie, the son of a travelling droll teller, as he journeys across Cornwall, a land steeped in myth and legend. Along the way you will hear mysterious and exciting tales like what happened when Bodrugan took his soldiers to capture Richard Edgcumbe, why the ghost of Lady Emma was never seen again, what proper job King Arthur gave the Giant and how St Piran came to settle in Cornwall. These stories – specially chosen to be enjoyed by 7- to 11-year-old readers – sparkle with magic and explode with adventure. As old as the moors and as wild as the sea, they have been freshly re-told for today's readers by storyteller Mike O'Connor.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 117

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

My grandchildren:Charlie and Ellie Pearson.The best proofreaders ever!

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mike O’Connor, 2018

The right of Mike O’Connor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8860 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

About the Author and Illustrator

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Torpoint: The Droll Teller’s Son

2 Cotehele: The Hunting of Edgcumbe

3 Mount Edgcumbe: The Lady and the Sexton

4 Liskeard: Bat Rowe’s Bear

5 St Neot, the Stags and Crows’ Pound

6 Bodmin: The Monks of Laon

7 Port Quin: The Watcher of the West

8 Tintagel: Arthur’s Birth, The Sword in the Stone, Excalibur

9 Bude: Arthur and the Great Boar

10 Davidstow: The Old Goose Woman

11 Camelford: The Last Battle, Excalibur, The Chough

12 St Teath: Anne Jeffries and the Fairies

13 St Breock: Jan Tregeagle

14 Padstow: The Little Horsemen

15 Padstow: Davy and the King of the Fishes

16 Bedruthan: The Giant’s Steps

17 Crantock and the Dove

18 Perranporth: St Piran

19 Ladock: The Wrestler and the Demon

20 The Feathered Fiend of Ladock

21 The Battle of Penryn

22 The Ghost of Stithians

23 Praze: Sam Jago’s Last Day at School

24 St Ives: John Knill

25 Zennor: Betsy and the Bell

26 Zennor: The Mermaid of Zennor

27 St Just: The Wrestlers of Carn Kenidjack

28 Mousehole: Tom Bawcock

29 Marazion: St Michael and the Mount, Cormoran’s Breakfast

30 Marazion: Tom the Tinner

31 Prussia Cove: The King of Prussia

32 Cury: Every Summer a Song

Adro dhe’n Awtour ha Lymnores

About the Author and Illustrator

MIKE O’CONNOR OBE is an expert in folklore and ancient music from his home of Cornwall. He is known for his work for the TV series Poldark: selecting and arranging the historical music and writing lovely songs for Demelza. Among folklorists he is known as a great storyteller and for his research of the world of travelling storytellers in Cornwall, a world described in his best-selling Cornish Folk Tales and revisited in this book.

Mike is a storyteller, fiddler, and singer, as is Anthony James, one of this book’s heroes. Sometimes writer and character are hard to separate!

MICHELLE O’CONNOR, Mike’s daughter, is an artist and art teacher. She too is deeply engaged in traditional arts: dancing, singing, and playing the violin.

She understands the stories and their Cornish landscape intimately. She knows that sometimes the stories seem to grow from the land of their birth, and that is reflected in her atmospheric illustrations.

In creating this book it’s as if father and daughter are travelling the lanes of Cornwall together, in the footsteps of Anthony and Jamie, swapping stories, writing and sketching as the miles and words flow past.

Aswonvosow

Acknowledgements

I thank Maga Kernow for Cornish language advice, Michelle for her great illustrations, my fellow storytellers for their inspiration and encouragement, the storytellers of old for keeping the culture alive, and Anthony James, for taking us all on wonderful journeys and always bringing us safely home.

(Mike)

Raglavar

Introduction

This book tells some of the best folk tales from Cornwall. Also, it is the story of Anthony James, a travelling storyteller. Anthony was born about 1767 in Cury, on the Lizard. He learned the fiddle as a lad, and could play at dances and sing to entertain. Britain was then at war with France and Anthony served overseas in the army, but in the last years of the century he lost his sight and was repatriated. A military pensioner, he was accommodated in Stoke Military Hospital, Devonport in the Winter, but in Spring he crossed the Tamar to earn a living.

Anthony was known as a ‘droll teller’. In Cornish dialect a ‘droll’ is a story, delivered in speech, rhyme, song, or any combination. The word’s origin is the Cornish word ‘drolla’, meaning folk tale. Guided by his son, Jamie, Anthony walked the Duchy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, living on tales, songs and tunes.

Like Anthony, most of the ‘supporting cast’ are also real, though I have changed a few dates.

Cornwall is a special land with a unique culture. Once independent, it has its own classical literature, music and its own Celtic language. Though in decline, the Cornish language was then still spoken in the far West, especially by fishermen and smugglers …

Anthony is fondly remembered as being from times past. But his stories and songs live on. So, let us start our journey. Once again let us travel through Cornwall with Anthony James.

To help us on the road each chapter has a riddle associated with it. The answer is usually at the end of each chapter.

In many places we would begin ‘once upon a time’. But this is Cornwall, so ‘En termyn eus passyes …’

1

ONAN

Torpoint: The Droll Teller’s Son

In my bed I never sleep,

I often run but never walk,

Slow and wide or fast and steep,

I often murmur, never talk.

Beside the great river it was very dark. Young Jamie had been there all night, waiting and watching. He could hear the lapping of the water; it was nearly high tide. Then he heard oars splashing and voices in the darkness.

Then the first light etched the hills. He could see the outline of the ferry. In the bow was a tall figure. Jamie’s heart raced. He had waited for this moment for a long time.

‘Dad!’ he shouted. The tall figure waved.

The ferryman moored the boat then helped the tall man ashore. The tall man offered money but the ferryman laughed and shook his head.

‘No sir,’ he said. ‘Your tale paid the fare. I haven’t laughed so much for ages.’

The tall man held a stick which he swept from side to side as he stepped forwards.

‘Jamie!’ he called. The boy ran to him and gave him a great big hug.

Jamie was a bright lad, but he had never been to school. In those days only the children of rich people went to school.

Jamie lived in the village of Cury in West Cornwall. His mum taught him to count: ‘onan, dew, tri, peswar, pymp*’, and to say the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Agan Tas nei, eus yn nev* …’. People there spoke Cornish as much as English.

Importantly he learned the words ‘En termyn eus passyes’ which is like ‘Once upon a time’. This was because Jamie’s dad, Anthony James, was a storyteller. Blinded in the wars with the French, in Winter he lived in Plymouth in a military hospital.

But now it was Summer. Jamie had made his way to the River Tamar to meet his dad. For when the days were warm Anthony James went round Cornwall telling stories, playing his fiddle and singing songs. He was a travelling droll teller and young Jamie was his guide.

Each had a pack on his back and each carried a fiddle. In their heads was a world of stories, songs and tunes. Together they began walking across Cornwall.

Where the going was good Anthony would walk unaided, tapping his stick against the kerb or wall. Where the road was rough Anthony would place a hand on Jamie’s shoulder. But now, such was their joy at being together, that though the road was good they held hands tightly.

Then Anthony spoke. ‘Jamie, it’s 75 miles from Cury to Torpoint. How did you do it?’

Jamie laughed, ‘Two days ago I walked towards Helston. I met Mr Sandys from Carwythennack. He asked a carter and got me a ride to Falmouth. There I met Frosty Foss the droll teller. His cousin drives the mail coach and I travelled with him. I sang songs all the way. In Bodmin I found Billy Hicks in Honey Street. He let me sleep by his fire. Next morning he gave me porridge. Then he spoke to another coachman so I got another ride. I saw Bill Chubb when they changed horses in Liskeard – he waved to me.’

‘Jamie,’ smiled Anthony, ‘you are a wonder.’

Then as they walked they swapped jokes, riddles and tall tales: the very best way to make the miles fly past.

(A river)

______________

* onan, dew, tri, peswar, pymp – counting one to five in cornish.

* agan tas nei, eus yn nev – ‘our Father, who art in heaven…’

2

DEW

Cotehele: The Hunting of Edgcumbe

Every day, I never move,

I never change my stance.

I go from Launceston to Liskeard,

But never Plymouth to Penzance.

‘This is Edgcumbe country,’ said Anthony. ‘The Earl of Mount Edgcumbe that is. South is his mansion: Mount Edgcumbe. Up river is his house of Cotehele.’

‘The Earl knew about Robin Hood. Do you remember when Robin hid underwater in a river and breathed through a reed?’

The Hunting of Edgcumbe

Richard Edgcumbe of Cotehele and Henry Trenowth of Bodrugan were deadly enemies.

One day Bodrugan brought his soldiers to capture Richard. They nearly took him by surprise. But Richard heard the hue and cry at Cotehele gatehouse. He was outnumbered so he fled through the servants’ quarters, out of the back door and into the kitchen garden, chased by Bodrugan’s men.

Richard hid among the trees above the River Tamar, but then he was spotted. The only way he could go was down towards the river. He said, ‘If I escape I’ll find a way to thank God.’

It seemed that Richard must either fight or drown. But he was outnumbered ten to one. Then he remembered Robin Hood. He waded into the river, throwing his cap into the stream where it would be seen by Henry’s men. Then he plucked a reed and hid under the water, breathing through the reed like a straw.

Bodrugan looked everywhere for Richard, then he saw that his hat was floating in the middle of the river. He thought Richard had drowned.

Richard hid until Bodrugan’s men left. Then at night a boatman rowed him down the River Tamar to Saltash and from there he escaped to Brittany. Eventually he had his revenge on Bodrugan, but that is another story.

In Cotehele woods beside the River Tamar, where Richard Edgcumbe outwitted his pursuers, there is a chapel built by Richard to give thanks for his escape. It’s dedicated to Saint George and Thomas à Beckett, but everyone just calls it the ‘Chapel in the Woods’.

(A road)

3

TREI

Mount Edgcumbe: The Lady and the Sexton

Little Nancy Etticoat

In a white petticoat,

And a red nose.

The longer she stands

The shorter she grows.

George Edgcumbe’s parties were the very best; everyone looked forward to them.

George was the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe and in 1761 he married a charming young lady called Emma, daughter of the Archbishop of York.

So that year all their family gathered for a very special Christmas party at their house of Cotehele. But on Christmas morning, when the Earl came down to breakfast, there was no sign of his wife. ‘Strange,’ he thought, for she was an early riser. A maid was sent to the Lady’s room. She returned, weeping, ‘I think Lady Emma’s dead.’

George rushed upstairs. His wife lay in bed, deathly pale. The doctor came. He said there was no sign of life. George was very sad. On his wife’s finger was the beautiful engagement ring he had given her just a few months before.

The body of Lady Emma was put in a coffin and loaded onto a boat. With muffled oars it was rowed down the River Tamar to Mount Edgcumbe. Solemnly a hearse carried it to Maker Church. Everyone watched as it was placed in the Edgcumbe vault. There was the Earl, the servants, the coachmen, the boatmen, the vicar, the churchwardens and even the sexton (the church’s caretaker).

They then went home, all very sad at the loss of this beautiful young lady. All that is, but one. The sexton ate his supper that night with a grim smile on his face.

As soon as it was dark he took a candle lantern and a sharp knife and returned to the church. Silently he entered the Edgcumbe vault and put the lantern on a handy tomb. He prised open the coffin and raised the lid. There was the body of Lady Emma. Her skin was deathly white. A rose had been placed at her throat, and her hands were crossed on her chest. On her left hand was the diamond ring. It sparkled in the candlelight.

The sexton tugged the ring. It would not move. He tugged again. Still it did not move. So he took his knife and placed it against the ring finger. He held the blade against the flesh. He pressed harder.

‘AAARGH!’ he screamed, as Lady Emma sat bolt upright in the coffin and looked straight towards him. Abandoning his lantern he fled, screaming, into the night. Later he was found in Millbrook village, babbling wildly.

That evening the Earl dined alone at Mount Edgcumbe House. He had forgotten all about Christmas and parties. As he ate he looked from the window. He saw an eerie light approaching through the trees. As it drew closer he saw a pale female form in a funeral shroud, carrying a candle lantern, walking straight towards him. He recognised his own wife; he thought it was a ghost.