Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Before schooling was widely available, for most people the classroom was at the fireside, the field and the country lane, where the bards told their tales. Many such folk tales exist to convey life-lessons in an entertaining way. These stories are not the pontifications of ancient philosophers: they are the gleanings of countless storytellers, everyday men and women with hard-won life experiences and pockets full of folklore. The tales reflect the times and places of their origin, but have been handed down from generation to generation, evolving to meet changing times. Some are amusing; some are thought-provoking; all have been polished and honed for so long that their message slips, almost imperceptibly, into the mind. Fools and Wise Men retells these stories for new generations – repaying our debts to the bards of old.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 271

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mike O’Connor, 2022

The right of Mike O’Connor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9076 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

INTRODUCTION

What are Wisdom Tales?

The Unjust World of Jack Madden

Retelling the Tales for Today

ON WISDOM

The Owl

Tom of Chyannor

The Three Advices of the King with the Red Soles

Nancherrow Bridge

Sam Jago’s Last Day at School

The Master and His Pupil

THE FAMILY

The Father and His Sons

Betty Stogs’ Baby

A Brewery of Eggshells

The Changeling of Brea Vean

The Eagles’ Nest

The Divided Blanket

Cap o’ Rushes

Grandfather’s Bag of Gold

PERSONAL QUALITIES

The Ant and the Dove

The Piskey Thresher

The Changeling and His Bagpipes

A Son of Adam

The Beggar and the Merchant

The Craig-y-Don Blacksmith

The Man in the Boat

The Small-tooth Dog

Three Heads of the Well

The Giant Fear

Fish on Friday

Canute and the Tide

How St Eloi was Cured

St Lateerin of Cullen

The Fox and the Craw

Robert Roberts and the Fairies

The Tramp and the Boots

FOOLS AND WISE MEN

The Three Wishes

The Clever Wish

The King’s Fool

The Wise Men of Gotham

Drowning Eels

A Pottle o’ Brains

A Changeling Musician

Lazy Jack

STRANGER DANGER

Mr Miacca

Gwrgan Farfdrwch’s Fable

OTHERWORLDS

The Forest

The Babes in the Wood

The Story of the Three Bears

The Haunted Wood

The Cave

Boleigh Fuggo

Tom Trevorrow

The Water’s Edge

The Haunted Mill-Pool of Trove

Jenny Greenteeth

Lutey and the Mermaid

The Man with the Green Weeds

The Night

My Own Self

The Pwca

Willy the Wisp

The Buried Moon

Jack o’ Lantern

FACING ETERNITY

The Woman and the Farmer

The Old Man and Death

Pat Makes a Deal with Death

The Hanging Game

Morgan of Melhuach

Death in a Nut

The Way Ahead

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

This book takes inspiration and tales from Victorian collectors such as Joseph Jacobs (1854–1916), pioneering scholars like Katharine Briggs (1898–1980), and from story tellers known to the author.

Duncan Williamson (1928–2007) was a Scottish Traveller and a hugely influential mine of folk tales. His tales ‘The King’s Fool’ and ‘Death in a Nut’ are copyright © The Estate of Duncan Williamson, and are included with the kind permission and assistance of Dr Linda Williamson.

Betsy Whyte (1919–88) was a celebrated Scottish Traveller, folk singer and story teller. Her tales ‘The Man in the Boat’, ‘Fish on Friday’ and ‘The Fox and the Craw’ are included with the kind permission of her great-grandson, David G. Pullar.

Taffy Thomas MBE (b. 1948) has been central to the revival of storytelling in England. Taffy is known for his sympathetic telling of traditional tales. He has a remarkably accurate memory for source tellers’ turns of phrase and his renditions are faithful without being parrot fashion. His tales ‘Giant Fear’ and ‘The Clever Wish’ are included with permission.

The Zennor tale ‘The Eagle’s Nest’, found above the desk of composer George Lloyd (1913–98), is included with the permission of Bill Lloyd.

I offer thanks to: Tina O’Connor, Del and Pippa Reid, Amy Douglas, and my friends at ‘Strong Words’ and Liskeard Storytelling Café for their insight, encouragement and support.

A story teller is a link in a chain, a reed in a river, one cloud in a storm of words. Tales are heard, learned, retold and passed on. I am grateful to be a bearer of this tradition.

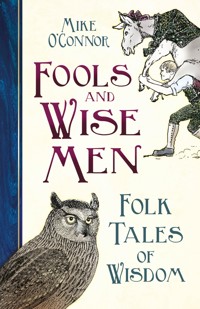

Illustrations

The illustration of Sam Jago on page 26 is copyright © Michelle O’Connor 2018, used with permission.

The other illustrations used in this book are all believed to be out of copyright.

J.D. Batten (1860–1932): Babes in the Wood, Brewery of Eggshells, Cap o’ Rushes, The Changeling and his Bagpipes, The Drowned Moon, Three Heads of a Well, Lazy Jack, The Master and His Pupil, My Own Self, Mr Miacca, The Pottle of Brains, The Three Wishes, The Three Bears, The Wise Men of Gotham.

P.J. Billinghurst (1871–1933): The Ant and the Dove.

J.T. Blight (1837–1911): Tom Trevorrow, Boleigh Fuggo, The Haunted Wood.

H. Thomson (1860–1920): Lutey and the Mermaid.

R. Heighway (1832–1917): The Fox and the Craw.

B. McManus (1869–1935): The Beggar and the Merchant.

A. de Neuville (1835–85): King Canute.

W. Pogany (1882–1955): The Man with the Green Weeds.

T.H. Thomas (1839–1915): The Pwca.

C. Whittingham (1767–1840): The Old Man and Death.

Other woodcuts are from the Dover Pictorial Archive and are reproduced in accordance with their terms and conditions.

The Tale, the Parable, and the Fable are all common and popular modes of conveying instruction.

George Fyler Townsend, preface to Aesop’s Fables, 1867.

Stories was wir education.

Duncan James Williamson, Scottish traveller (1928–2007).

If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) (attr.)1

__________________________________________________

1 Zipes, 1979. See https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2013/12/einsteins-folklore, accessed 13 January 2021.

Introduction

WHAT ARE WISDOM TALES?

A common way of categorising folk tales is by ‘type’: a classification by subject, content and form.2 But another method is by ‘function’ or ‘purpose’. The purposes of folk tales include explanation of creation and life (creation myths), societal or cultural reinforcement (tales of heroes, real or mythical), religious persuasion or reinforcement (tales of gods or holy persons), etiological tales (why things are as they are), puzzle tales (to foster debate) and entertainment. Importantly, many tales exist to inform behaviour and impart knowledge. Any tale may have more than one purpose.

Folklorist Stith Thompson devised a Motif Index in which Group J, ‘The Wise and the Foolish’, includes ‘the acquisition and possession of wisdom/knowledge, wise and unwise conduct, cleverness, and fools (and other unwise persons)’.3 But tales designed to teach, in other words wisdom tales, can include other motifs and be of various or multiple ‘types’. Story type and motif are the servants of function.4

The distinguished story teller Taffy Thomas once said to me, ‘Surely, all folk tales have wisdom.’ In the broadest sense this is true. A tale may not be literally true, but most contain elements of truth. Even the child intuitively comprehends that although these stories are unreal, they are not untrue.5

In the last half century many stories specifically identified as wisdom tales have become popular, often via motivational, religious or philosophical writers such as Idries Shah and Paulo Coelho. They show a market, a newly awakened need, for such stories.

But such tales have existed for thousands of years, from times when storytelling was a principal vehicle for education. Before schools were generally accessible, the classroom was the fireside, the field and the dusty road. The teachers were parents, grandparents, friends, and occasional travelling story tellers and visitors. Their tales were practical lessons from down-to-earth people, educated in the school of hard knocks and the university of life.

At their simplest, wisdom tales are proverbs and fables, Aesop’s being perhaps the earliest. But since their time, some 2,500 years ago, tales of Nasrudin, Akbar and Birbal, Coyote, Anansi, the omnipresent ‘Jack’ and many more have provided conventions and formats for the world’s story tellers. Animal characters, metaphor, and analogy abound.

The role of European wisdom tales has been overlooked due to cultural misapprehension or because classification systems do not neatly define them. This is shown by the common use of the term ‘fairy story’ to mean a lie rather than a meaningful product of the imagination.

Collections of multiple variants from widespread sources and different centuries tell us that wisdom tales were not fixed, but were often modified to meet changing cultural imperatives and evolving language. Even so, story tellers and publishers of past and present are sometimes criticised for ‘changing’ or ‘inventing’ tales. Such criticism often misunderstands the roles of those involved. Collectors record tales to preserve the past. Tellers tell their tales in the present. Publishers serve tellers and collectors, but re-present the tales for the future.

Some changes are made to make a tale coherent. ‘Mr Miacca’ was assembled by Joseph Jacobs from several incomplete versions. Other changes meet altered sensibilities. Jacobs changed the second wish in ‘Three Heads in A Well’ from sweet breath to sweet voice, as the idea of a woman with bad breath was unacceptable. A happy ending was added to ‘Babes in the Wood’. Many now understand that tellings, transcriptions, recordings and books are witnesses to a constant process of evolution, waymarkers on a journey.

However, some rewriting can be seen as manipulative. The brothers Grimm severely edited their collections, largely in response to Christian criticism. George Cruikshank earned the wrath of Charles Dickens for his heavy-handed rewriting of folk tales as teetotal parables.6 It is important to understand such changes.

Some tales become out of step with society’s concepts of reward and punishment. Consequently, they are changed or forgotten, as discussed in ‘The Unjust World of Jack Madden’.

Wisdom tales are an anarchic body of material. But paradoxically this world of imagination and allegorical fiction is, in the main, disciplined by experience, reality and fact. So it is that the tales remain relevant.

This book invites us to consider again wisdom tales from the British Isles, retold for our times. All are engaging, entertaining, and bright with truth.

THE UNJUST WORLD OF JACK MADDEN

While tales in oral tradition evolve to reflect time and place, tales in collections reflect the past. Most are as effective today as they were centuries ago. But a minority reflect past attitudes out of step with present sensibilities.

The justice of fairy tales can be severe and arbitrary, with frequent capital punishment. In ‘The Legend of Knockgrafton’, as a result of wishing to be cured of a disability, Jack Madden is punished with yet more disability. Sometimes such people are depicted as objectionable, to ‘justify’ the cruelty of the tale.

In stories a person’s appearance often reflects their inner qualities, so those thought ugly or disfigured are depicted as cruel, vindictive, or selfish. Misfortune or ill health is often the fault of the sufferer. The poor or disadvantaged are punished for not accepting their lot. Patriarchal attitudes are endorsed. Virginity is extolled above other female attributes.

Racial prejudice and xenophobia are found less often, as is religious prejudice, mostly against Jews, but also Anglicans, Catholics, Nonconformists, Muslims and unbelievers.

Such tales are relatively few, but they show that the prejudices or ignorance they represent were once widespread. Many reflect their times in a way we can understand and not take offence. However, others send messages that make them acceptable only as objects of study.

Story tellers are responsible for making moral judgements in choosing their repertoire. This can mean telling contentious tales with caveats, with changes, or not telling them. Such judgements ensure the relevance and wisdom of our stories.

RETELLING THE TALES FOR TODAY

The aim of this book is to retell tales for a broad readership in the twenty-first century. For that reason, they have been gently recast.

The tales have not been altered in themselves; the structure and the phrasing are largely unchanged. But the broadest colloquialisms and ponderous Victorian language have been softened, hopefully without affecting the character and regional identities of the tales.

Transcriptions contain repetitions, conjunctions and idioms natural in speech, but cumbersome on the page, and these have been carefully edited. This has been done with the approval of the relatives of source tellers and the knowledge that literal transcriptions are available.

Rewriting is a sensitive process. Throughout I have tried to use language that would be chosen by a sympathetic oral story teller of today, whilst retaining the identity of the original.

In past centuries, tales would often conclude with the cliché: ‘and the moral of the story is …’. We have not done this. When we all hear or read any tale, we should ask ourselves, ‘What is its message – and why?’

__________________________________________________

2 Uther, 2004.

3 The motif index is summarised in Thompson, 1946.

4 Briefly addressed in Killick and Thomas, 2007, p.4.

5 Bettelheim, 1975.

6 See Dickens’ essay ‘Frauds on the Fairies’ in his journal Household Words on 1 October 1853.

On Wisdom

THE OWL

A wise old owl lived in an oak;

The more he saw the less he spoke;

The less he spoke the more he heard.

Why can’t we all be like that wise old bird?

The best story tellers are the best listeners.

TOM OF CHYANNOR

En termen ez passies, thera trigas en St Leven, den ha bennen, en teller kreiez Tsei an Hur …

So begins the only surviving folk tale collected in the Cornish language.

In a time that is past, there lived in St Levan, a man and woman, in a place called Chy an Horth [the House of the Ram] …

Now Tom was a tin streamer, for in those days you still could sluice the black tin sand from the stream beds. But gradually all the tin had gone. Tom and his family fell on hard times. Tom had his wife to support and his daughter; sixteen years old she was, and the very image of her mother. So reluctantly Tom said a fond farewell to them both and set out to find work.

He had heard there was work to be had over in the east. So he walked for a day, and he walked for another day, and close to sunset he reached a farm near Praze an Beeble. There the farmer and his wife were kindly people, so Tom asked to be taken on as a farmhand. He agreed to work for a year for two gold pieces. For a year he worked long and he worked well. After twelve months the farmer said to him: ‘Here is your pay, but it’s been a hard year for the farm. If you give it back to me, I will give you something worth more than silver and gold.’ Tom thought, ‘If it’s worth more than silver and gold I’d best be having it.’ So, Tom agreed, but what the farmer gave him was a piece of advice; ‘a point of wisdom’ he called it, and the advice he got was this: never lodge in a house where an old man is married to a young wife.

Then Tom thought, ‘I still have nothing to take back to my wife and daughter.’ So, he agreed to work for another year for two more gold pieces. For another year he worked long and he worked well. After twelve months the farmer said: ‘Here is your pay, but it’s been a hard year for the farm. If you give it back, I will give you something worth more than strength.’ Tom thought, ‘If it really is worth more than strength then I’d best be having it.’ So, Tom again agreed, but again what the farmer gave him was a ‘point of wisdom’, and the advice he got was this: never forsake the old road for the new.

Then Tom thought, ‘I still have nothing to take back to my wife and daughter.’ So he agreed to work for yet another year for two more gold pieces. For that year he worked long and he worked well. After twelve months the farmer said: ‘Here is your pay, but it’s been a hard year. If you give it back, I will give you something worth more than gold and silver and strength.’ So once again Tom agreed, but once again what the farmer gave him was a piece of advice. The farmer said it was the best point of wisdom of all, and the advice he gave to Tom was this: never swear to anything seen through glass.

Then Tom decided that, though he had nothing to show for three years’ work, he would return to his wife and daughter. The farmer’s wife gave him a fine slab of heavy cake to take with him.

On the road Tom soon met some fellow travellers. They were merchants and they drove packhorses laden with wool from Helston Fair. They were going to Treen, not far from where Tom lived, so he was pleased to have some company on the road.

That night they reached an inn. When the door was opened Tom saw the landlord was an old man, but the landlady was a young woman. He remembered the first advice: never lodge in a house where an old man is married to a young wife. So he asked to sleep in the stable. That night he was woken by agitated voices. Looking through a knothole, he saw the young landlady talking to a monk, discussing how they had murdered the old landlord. But the monk stood near the knothole, and Tom was able to secretly cut a fragment of fabric from the monk’s gown with his penknife.

Next day Tom woke to find a gallows outside, for his friends the merchants had already been found guilty of the landlord’s murder. But Tom produced the fragment of cloth and told what he had heard, so the merchants were set free and went on their way, with many promises of rewards for Tom when their trading was over.

After a while they came to a fork in the road where a new shortcut had been made. ‘Come with us on the new road,’ said the merchants, but Tom remembered the second piece of advice: never forsake the old road for the new. So alone he took the old road. He’d only gone a few yards when he heard a hue and cry from over the hill. He ran across and found his new friends were being attacked by robbers. ‘One and all!’ cried Tom as he struck out with his walking stick and soon they sent the robbers flying. Then the merchants continued in safety with many thanks and more promises of reward.

So, after two days Tom got home. Looking in the window, he thought he saw his wife kissing a young man. His grip tightened on his stick, and he was about to burst in when he remembered the third advice: never swear to anything seen through glass. So, he put his stick back in his belt and tiptoed in to find it was his daughter, now a young woman and the very image of her mother, saying goodnight to her fiancé, Jan the cobbler.

Of course, they were all delighted to be together again. But then Tom had to explain to his wife that for three years’ work he had earned only cake and wisdom, to which his wife replied that he had earned nothing but cake! She was so vexed that she picked up the cake and threw it at Tom with all her might. Tom ducked and the cake missed him and smashed against the wall. As it did so it broke into pieces. Out fell not two or four or six, but fifteen gold pieces, all wrapped in a piece of paper. On it was written: ‘The reward of an honest Cornishman.’

THE THREE ADVICES OF THE KING WITH THE RED SOLES

When the chief of the Bonna Dearriga was on his deathbed he gave his son three pieces of advice, and warned that he would have bad luck if he did not follow them. The advice was this: first, never bring home an animal from a fair having been offered a fair price for it; second, never wear ragged clothes when asking a favour from a friend; and third, do not marry a wife whose family you do not know well.

The name of the son was Illan, called Donn, for that was the colour of his hair,7 and after his father’s funeral the first thing he did was set about testing the wisdom of his advice. So, he went to Tailtean8 fair with a fine mare to sell. He asked twenty gold rings for his mare, but the highest bid he got was only nineteen. But to test his father’s advice he would not accept this and rode the mare home in the evening.

On the way, Illan came to a river. He could have easily crossed it at a ford; but for sheer devilment he leaped the river higher up, where the banks were steep. The poor beast stumbled near the edge and was flung head first into the rocky stream and killed. Illan’s fall was broken by some shrubs on the opposite bank. He was as sorry for the poor mare as anyone could be. But, when he got home, he sent a giolla9 to cut off the animal’s two forelegs at the knee and, having had them properly prepared, these he mounted in the great hall of his dún.10

Next day, Illan went to the fair again and got into conversation with a rich chief of Oriel, whose handsome daughter had come to buy some cows. Illan offered to help, as he knew most of the bodachs11 and their wives who were there. A word to them from young Illan, and good bargains were given to the lady. So pleased were both father and daughter with this, that he was immediately given an invitation to hunt and fish at their northern rath,12 which he willingly accepted. So, he went home feeling very happy, and keen that this second experiment should succeed better than the first.

At the chief’s rath all was well. In the mornings there were pleasant walks in the woods with the young lady, while her little brother and sister were chasing one another through the trees, and hunting and fishing afterwards, and there were feasts of venison, and wild boar, and drinking of wine and mead in the evenings, and stories in verse recited by bards, and sometimes moonlight walks on the ramparts of the fort, and at last marriage was proposed and accepted.

One morning, as Illan was musing on the happiness that was before him, one of his promised bride’s handmaids came to his room. ‘You must be surprised at my visit, oh Illan Donn,’ she said, ‘but my respect for you will not allow me to see you fall into the pit that lies before you. Sadly, your fiancée is an unchaste woman. You will have seen crippled Fergus Rua, who plays the small cláirseach13 and who knows thrice fifty stories. He often goes to her room late in the evening to play to her, and to send her to sleep with soft music and stories of the Danaan druids.14 Who would suspect him, or the young lady of noble birth? By your hand, oh Illan of the brown hair, if you marry her, you will bring disgrace on yourself and your clan. She would willingly break off all connection with Fergus since she first laid eyes on you, but he has sworn to expose her before you and her father. If you do not trust my words, then trust your own senses. When the household is at rest tonight, wait at the entrance of the passage that leads to the women’s apartments. I will meet you there. By tomorrow morning you will need no one to tell you what to think or do.’

Before the sun tinged the purple clouds next morning, Illan was already crossing the outer moat of the lios,15 and on the back of his trusty steed, behind the saddle, was a long object carefully folded in skins. ‘Tell your honoured chief,’ he said to the gatekeeper, ‘that I suddenly have to leave, and that I request him, in his regard for me, to return my visit in a fortnight, and to bring his fair daughter with him.’ On he rode, muttering from time to time, ‘Oh, had I slain the guilty pair, it would be a well-merited death! The deformed wretch! The weak lost woman! Now for the third trial!’

Illan had a married sister, whose rath was about twelve old miles from his. Next day he went to her home. On the way he swapped clothes with a beggar whom he met on the road. When he arrived, he found that they were at dinner, and several neighbouring families with them in the great hall.

‘Tell my sister,’ he said to a giolla who was lounging at the door, ‘I wish to speak with her.’

‘Who is your sister?’ said the other in an insolent tone, for he did not recognise the young chief in his beggar’s clothes.

‘Who should she be but the Bean a Teagh,16 you rascal!’

The fellow began to laugh, but then the open palm of the young chief struck his cheek like a sledgehammer, knocked him to the ground, and set him a-roaring.

Then the lady of the house rushed to the door. ‘What has caused this confusion?’ she said.

‘I,’ said her brother, ‘punishing your giolla’s disrespect.’

‘Oh, brother, what has reduced you to such a condition?’

‘As I was on a visit at the house of my intended bride there was an attack on my house, and a raid made on my lands. Now I have neither gold nor silver vessels, nor rich cloaks, nor ornaments, nor arms for my followers. My cattle have been driven from my lands. You must help me; send cattle to my ravaged fields, gold and silver vessels, and ornaments and furs, and rich clothes to my house, so I can receive my bride and her father in a few days.’

‘Poor dear Illan!’ she answered. ‘My heart bleeds for you. I fear I cannot help you, nor can I ask you to join our company dressed in these rags. But you must be hungry; stay here till I send you some refreshment.’

She left him, and did not return, but an attendant came out with a griddle cake in one hand, and a porringer17 with some Danish beer in it in the other. Illan took them to the spot where he had left the beggar and gave him the griddle cake and made him drink the beer. Then, changing clothes with him, he rewarded him, and returned home, bearing the porringer as a trophy. In his hall he hung it from the wall.

On the day appointed, there gathered in Illan’s hall his sister, her husband, his fiancée, her father, and more beside. After supper, Illan spoke to them: ‘Friends and relations, I am going to confess some of my faults to you and hope you will learn from me. First, my dying father told me never to refuse a fair offer for an animal at a fair. For refusing a trifle less than I asked for my mare, there was nothing left to me but her forelegs that you see hanging by the wall. Second, he told me never to wear ragged clothes when asking a favour. I begged help of my sister for a pretended need, and because I was wearing a beggar’s cloak, I got only the porringer that you see dangling by the remains of my mare. Finally, my dying father told me not to marry a wife whose family I did not know well. Yet I wooed such a lady, but after responding to my advances, she at last said I should be satisfied with the crutches of her lame and deformed harper.’ Then Illan unwrapped the long package he had carried behind his saddle, saying, ‘And here they are!’

Illan’s sister was ready to sink through the floor for shame. His would-be bride was in a wretched state. Her father stormed and said it was a trick, but his daughter, torn with grief at the loss Illan’s love and respect, took the blame on herself.

The next morning the visitors had gone; but within a quarter of a year, the kind faced, though not beautiful, daughter of a neighbouring noble made the house merry by her presence. Illan had known her since they were children. He was long aware of her fine qualities but had never thought of her as a wife until the morning after his speech. He was fonder of her a month after his marriage than he was on the marriage morning, and much fonder when a year had gone by, and presented his house with an heir.

A tale redolent of past times and past attitudes. How would you tell this tale today? Could it be done?

NANCHERROW BRIDGE

If you go to Cape Cornwall and look north you will see a rocky, steepsided bay called Porth Ledden. At its northern side a stream tumbles into the ocean. That’s Nancherrow Water, it flows from high on the moors up by Carn Kenidjack, down past Nancherrow, through the Kenidjack Valley and so to the sea. Beyond lie the Isles of Scilly, and after that, Newfoundland.

Backalong ’twas no wonder if someone going from Penzance to Pendeen on a dark night should miss their way and think themselves led astray by the piskeys.

Leaving Penzance, there was neither bridge nor house in the hamlet now called New Bridge. Then beyond Cardew Water the road was just so many horse tracks, crossing each other and twisting about, round rocks and patches of furze, over miles of open downs and boggy moors. When one track was worn too deep it was never repaired, as there was plenty of room to make a new one. Bridges were few, and mostly made by placing flat slabs on the stepping stones in some of the deepest streams. Those old footbridges were nasty things to cross by night, the stepping stones were worse, and the most tricky of all were the stepping stones in Nancherrow Water. They had been there for as long as anyone could remember. They had been worn smooth by hobnails across and tin sand along, and when the stream was high many was the soul that took an unwelcome bath. It was that bad that no one would try and cross at night.

Now those were the days of the Poor Law and one of the overseers for the parish of St Just was a farmer who lived north of Nancherrow Water. His name was William Stevens. His task was to decide the levy on parishioners and make payments for the relief of the poor. It was a responsible job and time consuming, but straightforward, apart from dealing with claims from rascals like Treeve Pascoe, whom everyone suspected of making a handsome but well-concealed living from poaching, wrecking, and other nocturnal mischief.

But in those days, there were no schools for ordinary folks, and few could write, read or do sums. Anyone who could sign his name and read a psalm without spelling out the letters was considered a great scholar. Sadly, Willy Stevens was not one of those. He could neither read nor write. In particular, he could not add beyond ten; twenty if he took his boots off. So, to keep track of his payments to the poor, he kept his accounts in chalk on the dairy door, with big round Os for shillings and long chalks for pence. On the last Saturday of each month he would take the dairy door off its hinges, tie it on his back and carry it down to Nancherrow, across the river, and up to St Just Church-town, where the priest would enter his accounts in the ledger.