Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

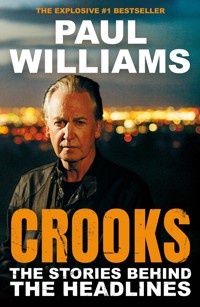

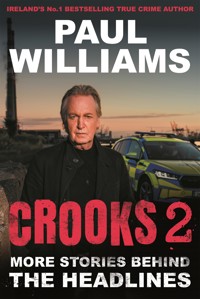

In this sequel to the explosive bestseller Crooks, Paul Williams reveals the inside stories behind more of his biggest scoops. Beginning with a sex scandal that rocked the Catholic Church, Crooks 2 shows us the personal side of some of Williams' most notorious exposés, from the unmasking of one of the world's most infamous drug traffickers to thwarting a criminal's political ambitions, covering the longest gang war in Irish history and disclosing the greed of the nation's bankers with the Anglo Tapes. For forty years Williams has shone a light where others dare not look, helping victims find their voices. In Crooks 2 he brings us inside the world of undercover operations, stings and stakeouts in the way that only he can.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 601

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY PAUL WILLIAMS

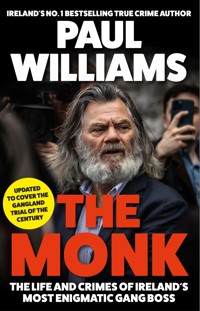

CrooksGilliganThe MonkAlmost the Perfect MurderMurder Inc.BadfellasCrime WarsThe UntouchablesCrimelordsEvil EmpireGanglandSecret Love (ghostwriter)The General

Paul Williams is Ireland’s leading crime writer and one of its most respected journalists. For over three decades his courageous and ground-breaking investigative work has won him multiple awards. He is the author of thirteen previous bestselling books and has also researched, written and presented a number of major TV crime series. His first book, The General, was adapted for the award-winning movie of the same name by John Boorman. He is a former presenter on Newstalk Breakfast and currently writes for the Irish Independent. Williams holds an MA in Criminology and is a registered member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists based in Washington, DC.

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © 2025 by Paul Williams

The moral right of Paul Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

All photographs in the picture section have been supplied by the author.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 80546 597 3

E-book ISBN 978 1 80546 598 0

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground

Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

To the many extraordinary and inspiring peoplewho trusted me to tell their stories.

And to my dear friend Joe Duffy, the voice of thepeople. The best president Ireland never had.

CONTENTS

Prologue: Grooming a New Generation

CHAPTER ONE:

Shooting the Messengers

CHAPTER TWO:

Exposing the Church’s Dirty Secrets

CHAPTER THREE:

Tracking Down the Pimpernel of International Organized Crime

CHAPTER FOUR:

Revealing ‘Mr Big’

CHAPTER FIVE:

Mikey Kelly – the Gangster Politician

CHAPTER SIX:

Exposing Gangland’s Jimmy Savile

CHAPTER SEVEN:

The Accidental Hero and the Terror of Murder Inc.

CHAPTER EIGHT:

Murdering the Innocent, a Hero’s Stand and the Mob’s Downfall

CHAPTER NINE:

The Anglo Tapes and the Crime of the Century

CHAPTER TEN:

An Army Reservist, Training a Terrorist and Joining the Rangers

Epilogue: Full Circle

Acknowledgements

PROLOGUE

GROOMING A NEW GENERATION

The two detectives stopped and searched the thirteen-year-old boy as he walked through the desolate Limerick ghetto that the gangs had claimed as their territory. The mob had embarked on their version of social engineering, using intimidation and violence to force decent people out of their homes as they turned the area into an open lawless prison for the remaining inhabitants, especially the kids.

I stood in the background with a baseball cap pulled down tight around my head to prevent being spotted and causing all hell to break loose. Other members of the four-member squad, who were covering their colleagues with machine guns, also wore baseball caps so I didn’t stand out. I was there to do a fly-on-the-wall feature as part of my coverage of the longest, most brutal gang war in Irish criminal history.

The heavily armed cops were members of a specialist team sent from Dublin to break the grip of Limerick’s notorious Murder Inc. mob. It was a cold morning in February 2009 at the height of the madness that had engulfed the city.

The cops suspected the young lad was one of the gang’s low level street dealers. He was wearing the uniform of a teenage foot soldier: new designer tracksuit, hoodie and runners. There was no way that his parents could afford to buy the expensive gear for him. He was also supposed to be in school that morning. His parents probably didn’t care about what he was up to.

The search proved negative. The kid had nothing on him.

I watched as the detectives tried to engage with the shifty teenager. Part of the unit’s policing strategy was attempting to reach out to the small army of youngsters the gang groomed and then forced to do their dirty work. The kids were being used to distribute drugs, move guns, carry out arson attacks, throw bombs and even kill.

I was witnessing a microcosm of a sociological disaster, a new phenomenon in the world of organized crime – how throughout Ireland impressionable, vulnerable children, mainly boys, were being groomed and enslaved by dangerous gangsters in much the same way predatory paedophiles select their victims. Since the boom in the drug trade in the late 1990s gangs have realized the value of using kids, some as young as ten. Within the criminal hierarchy immature foot soldiers are at the bottom of the food chain and are exploitable, dispensable assets.

Children living in deprived estates across the country are routinely seduced into crime with the offer of riches and a hedonistic lifestyle. Many of them come from already chaotic, dysfunctional family situations that include drugs, petty crime and mental health issues. They are invariably allowed to run wild and have problems at school. Some suffer from undiagnosed disorders such as ADHD and autism making them particularly vulnerable. Others come from decent families but are lured away from their hard-pressed parents who cannot afford the luxuries on offer in the gangster’s paradise. There is also the immature perception that being part of a gang means that ordinary people are afraid of them. These children are easily manipulated. Once they have been sucked into the vortex and it is too late, they find themselves trapped through drug debts and fear. Like boy soldiers in wars around the world they are indoctrinated by the gang cult.

Traditionally the pathway to crime begins when boys are in their early teens. Practically every criminal I have ever encountered began their career as a youngster. Some worked their way up to become household names. Many, like Daniel Kinahan, follow in their father’s footsteps.

Over the years I have sat with innumerable heartbroken, helpless parents who lost their children to the mobs. The reminders were always there on the mantelpieces: smiling faces of the innocent who became hopeless junkies or died from drug overdoses. Others were beaten, shot or murdered. Some had been driven to suicide to escape the despair. More had ended up in prison serving long sentences after being given no choice but to commit serious crimes including murder.

Then there were the terrified families I met who were forced to borrow money they cannot afford to pay off their children’s drug debts rather than see them maimed or killed. So many lives are destroyed by the virus of the criminal drug culture.

A major academic project conducted over several years by the University of Limerick revealed that up to 1000 children across the State are involved with criminal networks, some of whom are as young as eight years old. Based on my own experiences and from talking to police and social workers I believe that figure to be very conservative.

The most grotesque example of how children can fall prey occurred in Drogheda in 2020 when two local mobs began feuding. In January seventeen-year-old Keane Mulready-Woods was abducted and murdered by a notorious Dublin killer called Robbie Lawlor. The thirty-five-year-old, who already had four murders to his name, was determined to send a chilling message to his enemies.

Together with his cronies Lawlor deliberately dismembered the teenager’s body. Some of the severed limbs were stuffed into a sports bag which was then dumped on a street in Darndale, north Dublin, for young kids to find. Other body parts were discovered in a burnt out car the following day in nearby Drumcondra. A few months later the boy’s torso was found in Drogheda, Co. Louth.

The unconscionable act of mindless barbarism, reminiscent of the Colombian and Mexican narcos, was one of the most shocking incidents ever recorded in the fifty-year history of organized crime in Ireland. Lawlor wanted to send a clear message out with no fear of the consequences, to demonstrate that there were no longer any boundaries beyond which the monsters would not cross.

Like the thirteen-year-old wannabe gangster in Limerick, Keane Mulready-Woods was lured to the dark side when he was in his early teens. He thrived on the prestige of being part of the gang and the money he earned from selling drugs in the Drogheda estates. Keane also splashed the cash on designer tracksuits and matching runners. When the feud kicked off he was a willing soldier and had been involved in many of the seventy plus incidents of arson and serious assaults connected to it before his demise.

Keane wanted to make a name for himself. Instead his name will be forever remembered as the victim of a murder that horrified an entire nation. Lawlor was later assassinated on a street in Belfast. No one shed any tears for the monster. But by then he had left his grisly bloodstained mark on history.

One youngster who found himself in the clutches of the drug gangs bluntly described the type of people who turned teenagers like Keane into victims and killers:

Scumbags to the highest degree – they’re all junked up, they’re all on steroids. . . They’re all fucked up in the head, they’re manic in the head. They’re very dangerous people.

He added that he was living in fear of his life and the lives of his family because ‘they threaten your mother’s house’. He claimed that he had witnessed an ‘awful lot of beatings’ being dished out to customers and dealers who owed money or were being deliberately extorted for money they didn’t owe.

In recent years the Government has introduced legislation and extended social services to curb the phenomenon of young people being groomed for a life of crime. The gardaí launched specialist units to specifically target gangs involved in drug debt intimidation against innocent families. The problem is that Ireland’s administrative infrastructure and its agencies have not kept pace with an expanding population and the demands of an increasingly complex, troubled society. It means that the State will always have to play the game of catch up. Sometimes in my darkest moments I am tempted to think that it is all a bit too late.

In Limerick on that icy February day in 2009 the gardaí examined the teenager’s expensive mobile phone. It was another status symbol for juvenile criminals seduced by the bling lifestyle offered by Murder Inc.

Just then a text popped up. It was from one of the senior figures in the mob, a brutal thug called Jimmy Collins who had already introduced his own children to crime. It read: ‘Where in fuck are ya’. . . move yer arse if you wanna b a drug dealer.’

One of the cops showed me the text without speaking. The message said it all and confirmed their suspicions that the kid was indeed a courier for the mob.

The cop handed the kid back his precious phone and tried in vain to talk some sense into him. He told the aspiring drug peddler that the likes of Collins or his psychotic bosses, the Dundon/McCarthys, had no concern for him or his mates and that he was just being used and abused. ‘You know if you keep down this road it will end in disaster; you’ll end up in prison or be killed. . . or both,’ said the garda, as if he was talking to his own child.

‘We know lads like you are afraid of these boys. They’ll ruin your life like they have a lot of other young lads around this city,’ he continued, as the teenage gangster looked down, kicking stones with his expensive new runners.

Then he asked petulantly: ‘Can I go now?’ Without another word he shrugged his shoulders and laughed before moving his arse as the text demanded.

‘That tells you everything you need to know about this place. . . the kids don’t know any better,’ one of the officers remarked as we went back to the police jeep.

‘That lad is like a lot of them around here. . . he’s beyond saving. . . it is depressing to watch.’

CHAPTER ONE

SHOOTING THE MESSENGERS

The taste of blood swirled around my mouth as one of the most dangerous terrorist crime lords in Ireland came barrelling towards me in a fearsome rage. The strange thing was that there was no blood. It was as if my unconscious brain was anticipating what seemed like the inevitable – a serious beating that might well require me being fed through a tube into the foreseeable future.

I have never experienced such a sensation either before or since. But after all the years of confronting nasty, violent people it seemed to be programmed into my mental hard drive. As the six-foot plus, muscle-bound thug drew within punching range my five-footeight frame tensed up and I braced for the impact.

I remember the incident as if it were yesterday. It was a sunny afternoon in April 2011 and the guy coming at me was one Alan Ryan, the Dublin leader of the dissident republican mob the Real IRA who I had been writing about for over two years. It was little wonder then that he got so angry when I tracked him down to his hideout.

The then thirty-year-old ‘revolutionary’ from Donaghmede in north Dublin was classified by gardaí as one of the top five most dangerous criminals in the country. The self-styled republican hero was an unlikely terrorist. He was only fourteen when the 1994 IRA ceasefire heralded the beginning of the peace process and the end of the Troubles which in any case had not affected him growing up in Dublin. But that hadn’t stopped him getting involved with the Real IRA (RIRA), one of the hybrid republican groups that sprouted up to oppose the peace. The RIRA was formed by members opposed to the Good Friday Agreement when they split from the Provos. Its membership comprised the dregs of the republican movement and opportunistic criminals.

Ryan had been radicalized in his teens and claimed to be fighting for a united Ireland. His ‘brave’ comrades were responsible for the Omagh bombing in 1998 which killed twenty-nine people, including a pregnant woman and her unborn twins, and left hundreds seriously injured. The bombing was the second worst atrocity recorded in the thirty years of the Troubles. The RIRA would carry out over thirty murders and several bomb attacks in the UK as part of their ‘war’.

Ryan was typical of the young thugs who were drawn into terrorism. He first came to the attention of the police around the same time as the Omagh outrage. He was eighteen when the Garda Special Branch caught him with a loaded firearm. A year later he and his older brother Anthony were arrested along with nine others when gardaí raided a RIRA training camp in an underground bunker at Stamullen, County Meath.

In 2001 the Special Criminal Court sentenced them to four years for being found in the terrorist training camp and he also got three years for possession of the firearm. Since his release from prison Ryan had worked his way up to become the leader of the Real IRA in Dublin and had been causing havoc for two years by the time I tasted blood in my mouth.

Ryan was a typical narcissist – an egotistical sociopath – who had more brawn than brains. Tall and handsome he was known as a womanizer who liked his lovers to refer to him as ‘the model’. The non-drinker acted like a mafia boss, surrounding himself with sycophantic followers and admiring women as he held court in a north inner-city pub, the Players Lounge, which served as his base of operations. The pub was owned by fellow republican sympathizer John Stokes, the father of former Celtic F.C. star Anthony Stokes.

As a key figure of the 32 County Sovereignty Movement, the RIRA’s political wing, Ryan’s fight for freedom involved protest marches and several attempts to cause riots and disturbances in Dublin. On one occasion Ryan and his fellow ‘patriots’ hijacked a peaceful student protest against government cutbacks and turned it into a mini riot. They were also involved in the Shell 2 Sea campaign to prevent a gas pipeline being constructed in County Mayo. In 2009 I presented a documentary for TV3 – now Virgin Media – exposing the organization’s sinister involvement in the protest. The Battle for the Gasfield led to several complaints to the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI) which found the programme to be fair, accurate and balanced.

Ryan once tried to impress an attractive female journalist by claiming that he could trace his republican heritage back to Wolfe Tone and insisted that he was trying to preserve the ideals of generations of dead ‘freedom fighters’ who had given their lives for Ireland. Amongst his heroes, he bragged, was Bobby Sands and the ‘eight’ other hunger strikers who died in 1981. The plucky reporter reminded him that there were in fact ten hunger strikers. She later reported that she had felt intimidated during the encounter.

Nevertheless the ill-informed ‘model’ portrayed himself as a brave patriot who was fighting to protect his community from the scourge of organized crime and a capitalist state. The truth was a lot less romantic. Ryan and his gang were parasites in the underworld eco system who thrived on the back of criminal activity. His mob was responsible for scores of incidents in which people were threatened, tortured, bombed and shot. He was connected to at least three gangland killings.

Ryan organized the murder of drug dealers on behalf of other drug dealers. Just like the Provisional IRA had done in Dublin back in the 1980s, Ryan and his hypocritical henchmen extorted money from drug dealers in return for allowing them to sell heroin and cocaine on the streets. A drug dealer could stay in business as long as they paid towards the republican fight for a united Ireland. If they didn’t, they were murdered. Many of the city’s gangsters were terrified of him.

Much to Ryan’s annoyance I had reported how some of the money had been sent north to fund the ‘war’ while he and his acolytes trousered the rest. In the Sunday World and then the Irish edition of the News of the World I had written extensively about how he controlled a vast protection racket targeting businesspeople, using the cover of a legitimate security company. I had also exposed the embarrassing fact that despite their terrorist convictions he and his brother had obtained licenses from the Private Security Authority, a state agency.

A number of weeks before I found Ryan’s hideout I interviewed two brothers who told how he forced them to shut down their new pub and flee for their lives to the UK. Shane and Stephen Simpson were threatened by the terror boss just days after they opened their business because it was competing with the Players Lounge down the street. The brothers closed the pub in less than a week of opening and then left the country after gardaí officially warned them that there was a threat against their lives.

After the story appeared on the front page of the Irish News of the World Ryan resorted to his lawyers in an attempt to silence us. They threatened us with legal action because we exposed their criminal and terror-related activities. As usual he played the victim card. His solicitor’s letter claimed:

In addition, the allegations made are reckless and dangerous to our client and have undoubtedly placed him and his family at grave risk. . . Our client denies also the accusation that is clearly to be inferred from the article, namely, that he is a member of an unlawful organization.

But that wasn’t his only attempt to shut me up. Earlier in 2011 garda intelligence sources, who had several informants in the RIRA ranks, also discovered that Ryan had sent gang members to reconnoitre my home with a view to launching an attack. They aborted their plans when they saw that there was a permanent armed garda presence at the house: I had been receiving full time police protection since 2003. Other criminals had done the same thing over the years. As I pointed out in Crooks I probably would not be here today if it wasn’t for the gardaí.

The garda intelligence revelation made me even more determined to inform the public of what he really was, especially to the people living in the neighbourhoods that he controlled. I wanted to confront him face to face because we had a lot to talk about. To do that I needed to get him somewhere that he was not surrounded by his thugs. Ryan was hard to find. But then in April a garda source tipped me off that he spent three days a week with his girlfriend and mother of his three-year-old daughter in rural County Carlow.

The couple had been living in a council house in Carlow Town until the council built her a comfortable bungalow just outside the village of Ballon where she grew up. Intelligence sources revealed that he was regularly visited there by members of the RIRA terrorist group from Belfast and well-known criminals. A local person had also called me about Ryan’s menacing presence. He said the local authority house had been fitted with expensive security cameras.

On the afternoon of Friday 22 April I decided to have a look and travelled to Ballon with two photographers from the Irish News of the World. The initial plan was that when we had located the house we would watch it in the hope of photographing Ryan in his hideout. Once we had the pictures in the bag I was going to knock on the door. At least that was the plan. To quote the Prussian military general Helmuth von Moltke, ‘no battle plan survives contact with the enemy’. The same applies to journalists staking out terrorist thugs.

We located the house on a narrow country road. It wasn’t hard to identify as it was the only one with CCTV cameras. We drove past it for an initial look. The photographers were in a second car driving behind mine. But there was no vantage point where we could watch it without being seen. As we drove past a second time Ryan spotted us. He was clearly on high alert. He jumped in his car and drove after our small convoy.

At a crossroads we stopped to turn around. Ryan drew alongside my car. When I rolled the window down he flew into a temper when he recognized me. I told him I was there to talk to him and said I would follow him back to the house. As we did I phoned the other guys and told them to make sure and get the pictures because the situation was likely to get messy. If it got violent I wanted them to get the pictures first and then call the ambulance and the cops. I told them to stay in their car so he didn’t see that they were snapping him.

Back at the house I parked on the roadside about sixty feet from where Ryan parked his BMW and stepped out to face him. That was when he came barrelling towards me with clenched fists and I mentally prepared myself for a spell in hospital. I was in fight or flight mode but had no intention of showing fear or making a run for it. It was one of those unplanned situations where you just stand your ground and hope for the best. As he came towards me I said, ‘I’m only here to talk to you.’ But just as he got close enough to justify my instinctive apprehension the photographer’s car also pulled up on the road.

Ryan looked over at the car and suddenly stopped. The photographer’s car had blacked out windows and in that fleeting moment I realized that he thought it contained armed garda bodyguards. It was well known in the underworld that I had police protection. The fact that he couldn’t see the lads and they remained in the car saved my bacon that day. They told me later that they had been shitting themselves and had no intention of getting out.

The underworld hardman was in an extremely hostile and angry mood. He ranted about me and the fucking guards turning up at his house to harass him. I shouted over him that I was only there to get a comment about his activities: I wanted to tell his side of the story. Just like every other criminal I had ever confronted Ryan portrayed himself as a victim from the start. He fumed as he looked between me and the ‘police’ car:

What’s your problem? Why are you doing coming to my home. . . what to fuck do you want with me? All the stuff that has been written about me is all lies made up by the guards and drug dealers, I am not goin’ to give you any statement so you can turn your tape off. You are putting my life and the safety of my partner and children in danger.

I told him I wanted to know about his involvement with the 32 County Sovereignty Committee Real IRA and the allegations swirling around him. When I took out my notebook to write down what he said I had to control the shake in my hand.

I am in the Sovereignty Movement, so what? I am a republican. Youse are saying that I have loads of money, but I can’t even pay for the NCT on my fucking car [04 BMW]. I have a passport for ten years and have only gone abroad once and that was to a wedding. I haven’t got a fucking penny.

I asked Ryan about his gang’s involvement in protection rackets and his involvement in forcing the Simpson brothers to shut their pub down. He ranted, as he continued swapping his view between me and the other car:

There is no truth that I have been involved in extortion. I am a republican who has stood up to drug dealers. I get hassle [from the police] because I stand up and am anti-drugs. I get harassed by the police because a bunch of drug dealers are sitting around a table and getting the cops to do their dirty work for them.

I asked Ryan about his arrest in connection with the murder of a drug dealer called Sean Winters a year earlier. ‘I was arrested because I happened to be in the area at the time. There were nine other people lifted why don’t you talk to them as well?’ he shouted.

Ryan then made a series of bizarre allegations about incidents between the gardaí and a number of notorious drug dealers in Dublin.

‘I have nothing to do with drugs. When members of the Provos got involved with drug dealers like Marlo Hyland I stood up and said it was wrong,’ Ryan claimed.

His girlfriend then interrupted and ordered us to leave the area. ‘You’re putting our lives at risk,’ she shouted at me.

When I pointed out that the only person putting anyone’s life at risk was Alan Ryan she did not want to know. Her parents also arrived at the house and then ordered me not to write anything about Ryan or their daughter.

‘You shouldn’t be calling to my house,’ Ryan continued. ‘I never went to your house.’ I responded: ‘But you did send your boys to my house, didn’t you Alan. . . what to fuck was that about?’ He denied it and claimed that it was just ‘shite talk’ from the guards.

The confrontation lasted for about twenty very tense minutes before Ryan and his entourage returned to the house. I told Ryan he could contact me any time if he wanted to talk. Then I got in my car and left – with the bogus cop car behind me. I had survived without a scratch and got more than I could have anticipated.

On 24 April we put Ryan on the front page and spread the story over three pages inside. It was a great scoop. As I have mentioned in the past the life stories of major criminals tend to have a common, predictable theme – the protagonists either end up in prison or are killed, or both. Alan Ryan was gunned down in the street near his home in Donaghamede in September 2012. The hitman was paid for by a major crime boss in north Dublin. My sources revealed at the time that a number of gangsters had pooled their resources to get rid of Ryan. I also discovered after his death that they could have saved their money. The leadership of the RIRA in Belfast had come to the same conclusion, that Ryan would ‘have to go’. His erratic behaviour was attracting too much attention from the media and the police, who had riddled Ryan’s organization with informants. On top of that the volatile terrorist had fallen out with other members of the terror gang. He had become a liability.

The RIRA and their political wing tried to turn Ryan into a martyr who died while fighting back against the scourge of the drug dealers. In an astonishing lapse on the part of garda management at the time, the dissident republicans took over the neighbourhood where he lived. A volley of shots was fired over his coffin as part of a paramilitary-style funeral. But the propaganda stunt made no difference. The public, especially the long-suffering people in his community, were glad to see the back of him, and he was quickly forgotten.

Eventually the RIRA also faded away into the back pages of history. They had to disband when the Garda Special Branch and the UK authorities broke the back of the mob.

The weekend following the funeral I wrote Ryan’s requiem for the Irish Independent. It was the first major feature piece I wrote for my new employer after the closure of the News of the World and then leaving The Irish Sun. In December 2012 I also wrote about the life and times of veteran criminal godfather Eamon Kelly who had been one of the most powerful figures in Irish organized crime since it first emerged four decades earlier. As a man of ‘respect’ Kelly had dealings with all the gangs and mentored the likes of Gerry Hutch, the Monk and Eamon Dunne, the Don. When Dunne became a liability Kelly gave the go-ahead for his assassination in 2010.

Kelly had locked horns with Alan Ryan when they attempted to extort money from him. In 2010 Kelly escaped a botched assassination attempt organized by Ryan when the attacker’s gun jammed. Kelly had been suspected of being involved in having Ryan executed. Ryan’s comrades, who were now calling themselves the ‘New IRA’, were successful the second time around. But they made a mess of it and left so much evidence behind that the killers were quickly caught and later convicted.

Over the years I have upset my fair share of individuals, like Ryan and Dunne, who I have exposed to the world. Mostly it was the crime lords who resorted to death threats and other nefarious means to silence me. But the exposés also included the Church, dodgy bankers and so-called respectable citizens, involved in crimes such as fraud or sexual abuse. These days the job of reporting news has never been more crucial or difficult.

One of the high-minded adages of our profession, which we learned in journalism school, states that media should ‘afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted’. I stopped repeating that line when I heard it being used by a racist, homophobic, ultra conservative ‘journalist’ who targeted me and others with lies that were later proven to be untrue. That individual was once lauded by the Irish media before everyone realized how toxic and basically insane that person actually was.

I prefer to quote one of the greatest journalists and writers of all time, George Orwell, who once said that journalism is about ‘printing something that someone does not want to be printed. All the rest is public relations.’ In nearly every story that is produced for public consumption the people who are written about can be broken into two broad categories: those who benefit from the publicity; and those who are utterly pissed off by it.

But in the era of declining revenues, fake news, artificial intelligence and the wholesale production of lies on social media traditional journalism faces an existential threat like never before. My journalistic colleagues, and by that I mean, professional, trained journalists and editors who work in newspapers, TV and radio, are under threat. I am not talking of the occupational hazard that crime reporters often endure – it is still the most dangerous end of the media profession in Ireland. Two of my colleagues and friends paid the ultimate price with their lives. Up to more recent times crime reporters were the only ones to suffer intimidation. But one of the most disturbing changes that has taken place since the murders of Veronica Guerin and Marty O’Hagan is that the intimidation of the media in general has intensified. Since it migrated to the sewers of social media keyboard warriors attempt to undermine and denigrate traditional journalism. The digital age has given a platform for every type of crank, extremist and criminal to vent what they like. They have no regard for facts and can say what they like while the mainstream media cannot.

The new threats come from all sides. Criminals, the far right and far left, including the woke brigade – the noisy minority – all act like bullies to censor and toxify legitimate public debate on a whole range of issues. They go on the attack and seek to cancel the proponents of free speech if they feel ‘offended’ or find what is said does not correspond with their own fundamentalist beliefs. Their concept of ‘free speech’ is that they alone have the exclusive right to speak freely and no one else. (Full disclosure here: I am a huge fan of Ricky Gervais.)

Appalling abuse is now routinely meted out to politicians, celebrities, journalists or anyone who dares put their head above the parapet and express a view. In 2025 the Tánaiste Simon Harris and his family were subjected to a shocking campaign of intimidation that included threats to attack his children. Several other politicians have suffered the same sordid abuse and intimidation which is unacceptable in a democratic society.

I recall a particularly appropriate remark Ireland’s respected and insightful broadcaster Joe Duffy once made about the anonymous ranting rabble. He said on air: ‘I think the best advice to them is that they should pull up their trousers, turn off the computer and go out for a walk in the fresh air.’ When Joe retired in 2025 it was a huge loss to the Irish broadcasting media.

Broadcasters and journalists are becoming more concerned about how to avoid inciting the cancel brigade than speaking the unvarnished truth. But they are not alone.

Also in the mix are some highly paid lawyers who perform a similar function on behalf of powerful individuals in the corporate and political spheres to scare off the media by launching expensive libel suits. Such actions are referred to as SLAPPs – Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation – which are filed to shut down negative publicity. While it might be a different kind of threatened ‘slap’ to the one I nearly got from Alan Ryan, they are both designed to shut down media inquiries. Traditional media are hobbled by draconian libel laws while social media, the biggest purveyor of defamation, largely goes untouched. The digital age is the new lawless frontier.

The charlatan-in-chief of the democratic world, Donald Trump, invented the term fake news to denigrate and demonize the legitimate press. His aim is to distract from his lies and deceit as he goes about dismantling freedom and human decency while pushing the world into a state of chaos before our very eyes. The histrionic Greek chorus on X and other platforms, including his most ardent critics in the woke brigade, regularly adopt Trumpian tactics.

As a result a free press has never been as important to society as it is today. Despite the fact that just like everything else in life it is not by any means perfect, a free press is an essential pillar of democratic liberal society. That is why it is the first victim of demagogues, dictators, terrorists and wrong doers. The term ‘mainstream media’ is now used pejoratively to undermine traditional journalism by claiming it represents vested interests and of toeing the government line. Gerry Hutch, the Monk, articulated that view after the 2024 general election when he was confronted with legitimate questions by RTÉ crime reporter Paul Reynolds. In a temper Hutch told Reynolds: ‘You get paid from the State and RTÉ, that’s what you do. The State is paying you to say this.’ (See Chapter 5.)

Legitimate professional media has also paid a huge price in human blood. When Veronica Guerin and Marty O’Hagan were murdered it shocked the world. Back then it was a rarity to see journalists killed for what they reported. Since their deaths, it is estimated over 1600 journalists have been killed as a result of their work. Some were murdered for investigating crime and corruption. Others have been killed in wars or, like Lyra McKee in Derry in 2019, found themselves caught in the crossfire of violence. For instance, in Mexico the drug cartels have murdered or disappeared over 160 media workers since 2000. And then there is the world’s most dangerous killing field – Gaza. As Israel continues to unleash genocide and famine on the Palestinian people the journalists reporting on the outrage have also been targeted. It is estimated that 270 journalists have been killed by Israeli forces since 2022. The various methods of shooting the messengers are creating a chilling effect on journalism which is bad for everyone in society.

I have not been a stranger to abuse by the faceless digital trolls over the years. But after experiencing so many threats over the decades you become inured to abuse. The social media nuts don’t bother me. But it is something which I try to advise younger journalists about: don’t let the bastards get you down. Nor do I ever take any pleasure seeing awful things being written about people I don’t like. I am aware that some journalists also hide behind anonymous accounts to spew their own venom. I don’t use social media apart from LinkedIn and have long since stopped looking at what is said about me. But it can be quite satisfying at times to know that you have pissed off certain groups. It means that I must have been doing something right.

In Crooks I told the story of how I locked horns with fraudster Giovanni Di Stefano. He came to Ireland posing as a high-powered lawyer who claimed he would win the freedom of some of the country’s most notorious gangsters. He was dubbed the ‘Devil’s Advocate’ having gained international notoriety as he claimed to represent the likes of Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein, and UK serial killers Harold Shipman and Ian Brady.

Before Twitter/X, he used a website to launch ferocious attacks designed to discredit and intimidate journalists who crossed him in the UK. In 2006 he turned his full focus onto me after I exposed him as a fraud who had no legal qualifications and was in fact a convicted criminal. He then embarked on a full-on assault on my character. He accused me of being a cocaine addict, an extortionist, a paedophile, a user of prostitutes, a serial philanderer and a perjurer. He even claimed that I was responsible for murder.

He also posted pictures of my home on his website which gained huge traction in Ireland. The pictures had been taken by members of Marlo Hyland’s gang when they staked out my home for possible attack. As in Ryan’s case, they backed off when they spotted the garda presence there. Di Stefano eventually ended up where he belonged – behind bars.

Back in the early days, before Twitter/X, Ryan and other dissident republican groups used similar means to attack me. In recent years the Monk’s acolytes lambasted me for months on end with every kind of rubbish. I took it as a compliment.

Ignoring it has been one of the many learning curves I experienced during my career. That is why I understand why so many journalists and editors are fearful of a social media backlash. Some outlets censor their own content just to avoid pissing off the digital warriors. As some of my great mentors over the years often reminded me: you are writing for the man in the street, not other journalists. That now includes the faceless social media brigade. There is no point in entering a combat zone if you’re not prepared for a fight. I treat the online attackers the same way I did the ones making physical threats: show the bastards that they won’t beat you down. In many ways I can thank Di Stefano for hardening me up for the many social media assaults I’ve experienced. There have been so many that I’ve lost count.

Shortly after the Kinahan/Hutch feud erupted in 2016 I was a guest on the Late Late Show with Ryan Tubridy and posited a history of the two mobs involved. As part of the appraisal I correctly predicted that the non-jury Special Criminal Court was going to be a vital weapon in taking on the powerful gangs, especially the Kinahan cartel. The mob would do everything in their power to undermine the rule of law with the money and means to corrupt and intimidate juries in other Irish courts. The SCC is our anti-mafia court. Then I exposed the inherent hypocrisy of Sinn Féin’s stance on organized crime, specifically the party’s determination to abolish the Special Criminal Court. There was a general election campaign going on at the time and getting rid of the court was in their manifesto for government.

Sinn Féin’s shadowy bosses in Belfast, who dictate what its elected representatives say and think, hate the SCC because it convicted so many IRA terrorists. I pointed out that the only people who would vote for that part of their manifesto were the crime bosses, the killers, the drug dealers and the kidnappers. As a result I trended on Twitter for days and was subjected to a torrent of vituperative abuse from the supporters of the supposedly democratic party, some of which included physical threats.

RTÉ received 128 formal complaints about the comments mostly from party supporters but only two proceeded to the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI), the media regulator – now called Coimisiún na Meán. The BAI later rejected them by a majority vote.

Sinn Féin quietly dropped their demands to abolish the SCC after the election because the public did not agree with their stance. Coincidentally Sinn Féin representatives are responsible for a disproportionate number of SLAPPS or threatened libel suits against the media in recent years – many more than the rest of the political establishment combined.

Another social media attack happened in July 2024, after I appeared with Pat Kenny on Newstalk to discuss anti-immigrant riots in Coolock, west Dublin. Similar riots had erupted in Dublin city centre in November 2023. I made the point that the opening of a migrant centre had provided an opportunity for some recreational mayhem by a group of anti-social thugs, many of whom were involved in crime. Like Alan Ryan they hitched their wagons to a cause – in this case the so-called far right – so that they could attack gardaí and burn things down in the ludicrous claim of defending their communities.

It is not a coincidence that dissident republicans are heavily involved with the far-right mob. The involvement in such causes benefits the participants in their criminal pursuits and gives them more power to intimidate the communities where they live. I suggested that garda chiefs were wrong to order their officers to stand back when they should have used their legitimate powers and baton charged the thugs off the streets.

I pointed out that while this country has a major problem with unregulated immigration that needs to be addressed, it was interesting that the far right never used their power to confront the scourge of home-grown gangs who are terrorizing working-class estates. For a few hours I became the focus of the mob’s ire. Some of them pointed out where I lived and suggested I get a visit which clearly meant that those who did come would not be popping in for tea and a chat.

Proving that the vast majority of it is nothing more than hot air, the herd quickly moved onto its next target. But it illustrates how venomous keyboard warriors try to intimidate journalists and create a chilling effect on the media. I am well experienced in dealing with threats and intimidation, but it takes a huge toll on younger journalists who are simply reporting what is going on. I will continue to remind colleagues that coming under digital attack from these morons gives their work credibility.

In 2024 I marked forty years in journalism. During that time I have chronicled the evolution of organized crime in Ireland as a front seat observer in what was often a white-knuckle ride. Back then it was suggested by my publishing editors and some trusted friends that I should write a sort of semi-autobiographical book covering my personal experiences over that period. Basically they suggested taking my loyal readers on a ride-along behind the scenes of some of more notorious stories I worked on. The end product was the first volume of Crooks. I am deeply grateful to the readers who made it a bestseller.

I wrote about the first major godfathers I encountered, starting with the General and how he fuelled my interest in crime and criminology. It gave me a chance to tell how I witnessed gangland morph into a vast, multi-billion industry built on narcotics. Exhuming old ghosts by revisiting the dark corners of my career was at times an emotional experience. It brought back memories, both good and bad, of triumphs and loss. I relived many of the times that I came close to meeting the grim reaper and found myself admitting publicly for the first time that I suffered a bout of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Writing Crooks was cathartic. It also gave me an opportunity to acknowledge the many brilliant people I had the honour to work with and who helped me in my career. Crooks 2 is a continuation of the story of my personal journey.

Journalists everywhere have covered stories that they never forget the same way cops have cases that always live with them. Some stories have a tendency to pop up many years after they were first told. I have had many stories that I cannot forget as the experience is burnt into my memory banks. My first-hand experiences over a fourteen-year period exposing the mind-boggling violence of Limerick’s Dundon/McCarthy clan, Murder Inc., in the longest, most brutal gang war in Irish criminal history is one of them.

As a journalist I have been nothing more than a conduit of information to the public. I have reported on the evil things bad people do to good people. In Crooks 2 I concentrate on some of the extraordinary people who trusted me to tell their stories: individuals who have encountered adversity in its most extreme form and survived. To me they are all heroes. I am honoured to say that many of them became dear friends.

The memories from my career in journalism are filled with an awesome cast of characters. But not all of them were criminals in the traditional sense. One of the biggest stories I worked on was exposing a different type of scandal, a moral crime if you will, which fascinated the Irish public three decades ago. It involved exposing the secret life of one of Ireland’s most famous and admired priests – Fr Michael Cleary.

CHAPTER TWO

EXPOSING THE CHURCH’S DIRTY SECRETS

On New Year’s Eve 1993 Father Michael Cleary, the celebrity priest and the Catholic Church’s most outspoken moral fundamentalist, died from lung cancer at the relatively young age of sixty. Coverage of the death of one of Ireland’s most famous clerics dominated the news bulletins. A succession of church leaders, former parishioners and famous friends fondly remembered the charismatic man of the cloth in a blizzard of valedictory sound bites and comments.

The TV news showed iconic footage of Cleary and his by then disgraced best friend, Bishop Eamonn Casey, as they entertained 300,000 young people prior to Pope John Paul II’s historic Youth Mass in Galway in 1979. It marked the high point of Cleary’s fame.

All I knew about Michael Cleary on New Year’s Day 1994 was what I had seen, heard or read of him in the media. Little did I know then that I would be the one who would reveal the secrets he had hoped to take with him to the grave.

Cleary’s image was that of a much-loved man of the people and hardline stalwart of Catholic doctrine. He came from a wealthy family and enjoyed a privileged upbringing. Ordained in 1958, he never conformed to the traditional image of the austere, aloof clergyman. In appearance Cleary was unmistakable in a crowd. A tall thin man six feet four inches in height, he wore glasses, a bushy red beard and had wiry thinning hair. The chain-smoking padre always had a cigarette dangling from his mouth.

As a curate in the 1960s he worked in Dublin’s most deprived parishes where he initiated some of the first outreach youth programmes at a time when the State provided little or no support to the disadvantaged in society. His image was that of a priest whose social work extended to supporting unmarried mothers in a less enlightened, cruel era when such women were incarcerated in notorious mother and baby homes. He also worked for a time in London where he was assigned to the Irish emigrant chaplaincy.

An accomplished raconteur who would sing, tell jokes and yarns for his adoring audiences Cleary was best known as the ‘singing priest’. He co-founded the All Priests Show which staged charity concerts across Ireland over many years. Through his showbiz connections he was a religious mentor to celebrities in the entertainment and media industries.

He enjoyed considerable fame as a TV celebrity and newspaper columnist writing for the Sunday Independent and the Irish Star so that he could reach people at all levels in society. Over the decades he was a regular guest on the country’s most watched TV programme, Gay Byrne’s Late Late Show.

When it was launched by RTÉ in the early 1960s, the Late Late Show was castigated as being dangerous to the nation’s moral well-being by the all-powerful Catholic establishment. Byrne was accused of corrupting the young by confronting issues of morality and sex that had never been discussed in public before. RTÉ came under intense pressure to ban the show. Cleary broke that taboo when he became the first priest ever to appear on it. He counted Ireland’s chat show king as one of his close friends.

From the 1980s Cleary hosted a popular nightly local radio show on Dublin’s 98FM where he freely expressed his conservative opinions and dispensed advice to listeners. The show was particularly popular amongst the inmates of Mountjoy Prison for whom he acted as a broadcast minister answering letters and music requests from his captive audience. He had a reputation for being a friend to both the poor and downtrodden as well as the rich and powerful.

That position made Cleary the poster boy of a church that had dominated every aspect of Irish life since the foundation of the State. Like Bishop Casey, he used his fame and affability to push Catholic doctrine on the Irish public. By appearing to be more down to earth than the average cleric he was one of the first Irish priests to present a more human face of the Church for a still largely devout, deferential population In reality Michael Cleary was one of the frontmen at the time when Ireland was still in the pedagogic, domineering grip of a hegemonic church. He used a blend of humour and jokes to deliver bombastic utterances on sin and morals.

My perception of Cleary was that of a moral boot boy who used his huge media profile to propagate the Church’s strict precepts on divorce, abortion, contraception and homosexuality. He influenced public debate during constitutional referenda on issues such as divorce or abortion, or when topical legislation perceived to conflict with church doctrine on issues of morality and sexuality was brought before parliament.

In 1990 he publicly returned his BA to University College Dublin (UCD), It was a protest against the university’s conferral of an honorary degree on a judge who had been instrumental in ruling abortion legal in the USA.

Cleary was particularly vocal in the run up to the country’s first referendum on abortion in 1992 in the wake of the X case. The amendment had been proposed after the High Court, working from the existing legislation regarding the right to travel for abortion, initially stopped the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) from taking a 14-year-old rape victim to the UK for a termination. The ruling was later overturned by the Supreme Court and the child had the abortion. In the referendum a majority of the electorate voted along church lines in supporting an unequivocal constitutional ban on abortion.

Two other amendments, which permitted people access to information about abortion in other countries and the freedom to travel abroad for terminations were passed despite church opposition. The referendum results epitomized the nation’s moral ambivalence: abortion was illegal but everyone knew countless thousands of Irish women were forced to travel in secret to the UK for terminations like they were criminals. It was kept out of sight and was like a parallel universe. It would take another twenty-six years before the country matured enough to eventually legalize abortion in a referendum in 2018.

I was in my twenties at the time of the first referendum and part of Generation X which was the first generation to begin the slow process of secularization by questioning the relevance and power of the Church. We began to call out the lack of empathy and understanding demonstrated by Cleary and his ilk. It was one of the reasons I wasn’t overwhelmed by the news of his demise.

In Crooks I told how my wife Anne incurred the wrath of the Catholic Church when, as a trainee reporter with the Longford Leader, she wrote a feminist column supporting a woman’s right to choose if she wanted an abortion.

Just over a decade earlier one of Ireland’s greatest writers John McGahern, who lived near my hometown of Ballinamore in County Leitrim, was sacked from his job as a teacher after his second novel, The Dark, was banned by a domineering church, led by the notorious Archbishop John Charles McQuaid. McGahern’s books were among the first I ever read.

Like most of my peers, I rebelled against the Church and was a confirmed agnostic by the time I hit my teens. I remember once being beaten by a teacher in Ballinamore secondary school because I could not recite the ‘Our Father’ in Irish. He succeeded in beating religion and an interest in the Irish language out of me. When I was doing my Leaving Cert in Carrigallen Vocational school in Leitrim in 1983 – after being expelled from two previous secondary schools – I refused to attend religion classes. When the priest running the class ordered me to attend I told him it was a waste of my time and I would be more constructively employed actually studying the subjects for the exams. I’d deal with God in my own way.

The priest, a Father Collins, complained bitterly to the principal Mick Duignan and suggested that I was a bad influence on the other kids. My recalcitrance, he suggested, should be countered with the threat of expulsion which would mean the end of my education. I was delighted when Duignan stood by me which was unusual at the time. Vocational schools were the first second-level State run institutions that were independent of religious orders which was why they played an important and understated role in our social evolution. I also received the backing of his deputy, Eamon Daly, who taught me English and the value of questioning the status quo. Although practising Catholics, my parents also agreed that I was right to stand up for myself. I had won my first battle to break away from the clutches of mother church.

I learned the rudiments of my job in the Rathmines School of Journalism. It produced the generation of future reporters and editors who would go on to expose the moral corruption and hypocrisy which helped bring about the end of the Church’s unquestioned role in Irish society. I remember reading an interview with a prominent priest in the 1980s who decried the educational revolution because better educated young people had begun to question the Church’s teachings. In 1993 I had no love or devotion for the Irish Church or its vociferous disciples.

Cleary had assisted in alienating our more liberal generation. A few years before his death, he used an appearance on the Late Late Show to condemn as a harlot a female journalist with the Sunday Independent. Cleary was responding to an honest opinion piece in which the woman confessed that she carried condoms in her handbag to avoid getting pregnant or contracting HIV. In the final decade of the 20th century, his denouncement highlighted how women were still seen as second class citizens in the patriarchal Catholic world.

On another occasion he infamously argued that condoms were not a reliable device for controlling the spread of AIDS, making the ludicrous claim that the virus was smaller than the pores in the condom. All these years later it is hard to imagine that we lived in a time when prominent people could get away with such vacuous nonsense. It was also hard to take at the time. In his 2021 book, We Don’t Know Ourselves, Fintan O’Toole wrote about how the younger generations staged a quiet revolution by navigating a path around the Church’s interference and got on with their lives.