9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

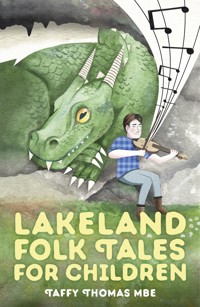

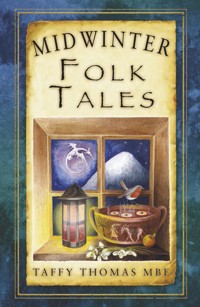

These engaging folk tales from Cumbria were collected as fragments that the author has brought back to life. Shaped by the natural world, local customs and generations of chattering, these traditional tales reflect the unique Cumbrian wit and wisdom. Herein you will find intriguing accounts of Hunchback and the Swan, the Screaming Skulls of Calgarth, the Millom Hob Thross, Hughie the Graeme, Cumbrian Crack, and Billy Peascod's Harp. They will make you want to visit the places where they happened and meet some of the characters that feature in them. Including charming illustrations from the local artist Steven Gregg, this captivating collection will be enjoyed by readers time and again. Taffy Thomas has lived in Grasmere for well over thirty years, and is a highly experienced storyteller with a repertoire of more than 300 tales. In the 2001 New Year Honours List he was awarded the MBE for services to storytelling and charity, and in 2010 was appointed as the first UK Storyteller Laureate.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

DEDICATION

‘Stories are like Fairy Gold: the more you give away, the more you have.’

To all Cumbrians who have come to hear my stories, and so generously shared theirs …

for stories truly abound in this most magical of counties.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

PART 1

OUT OF THE LAND

One

Long Meg

Two

Aira Force

Three

Hunchback and the Swan

Four

The Bishop’s Rock

Five

Urswick Tarn

Six

The Fell King

Seven

The Rock Climbers

Eight

The Parton Smugglers

Nine

The Hartshorn Tree

PART 2

SPECTRES AND SKULLS

One

The Claife Crier

Two

The Screaming Skulls of Calgarth

Three

The Spectre Army of Souter Fell

Four

The Chess Puzzle

Five

Girt Will o’ t’ Tarns

Six

The Legend of Armboth Hall

Seven

The Ghost Ship

Eight

The Slave Girl’s Revenge

Nine

The Grey Lady of Levens Hall

PART 3

FAIRIES, OAKMEN AND A HOB

One

The Vixen and the Oakmen

Two

The Beetham Fairy Steps

Three

The Millom Hob Thross

Four

The ‘Lucks’ of Cumbria

Five

Tom Cockle

PART 4

ROMANS, REIVERS AND NORSEMEN

One

How Mungrisdale got its Name

Two

Sealed with a Handshake

Three

Hughie the Graeme

Four

The Roman Wine Story

Five

The Three Friends

Six

The Ballad of Kinmont Willie

Seven

The Legend of Furness Abbey

Eight

The Horn of Egremont

PART 5

SHEPHERDS, HENWIVES AND STRANGERS TO THE TRUTH

One

Cumbrian Crack and the Hat that Paid

Two

A Woman’s Burden

Three

Riddle Women

Four

Yan, Tan, Tethera and the Seventeen Sheep

Five

John Peel and Friends

Six

Mary Baines, the Witch of Tebay

Seven

Witch of the Westmorelands

Eight

Dickie Doodle

Nine

Will Ritson and Strangers to the Truth

Ten

The Borrowdale Cuckoo

PART 6

SAINTSAND SINNERS

One

The Legend of Devil’s Bridge

Two

Billy Peasecod’s Harp

Three

Aileth

Four

Cartmel Priory

Five

St Bega

Six

The Generous Hand of St Oswald

Seven

The Legend of St Andrew’s Church

Eight

Down’t Lonnin’

In Conclusion

Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

FOREWORD

I recently sent a small collection of my serious poems to a well-respected literary journal – though mostly known as a comedian, monologuist and folk singer, I have long had another string to my bow as a writer of ‘serious’ poetry.

‘Not for us,’ came the sniffy reply, ‘The problem is that your poems tell stories.’

I decided when I read the editor’s words that when my next book of poems comes out it will be prefaced by a quote from American writer Tim O’Brien, from his book The Things They Carried, ‘But this I know, the stories save us.’ Stories do save us: they tell us who we were and where we came from; they take us into a world that sometimes, mystically, seems to make more sense than our supposed real world of hedge-fund managers and derivatives, high-speed rail links and The X-Factor.

Children love stories for the simple reason that they haven’t had the sense knocked out of them by all the rubbish we grown-ups have to put up with, and when we grown-ups get the chance to hear a good story – well, those of us who still have the spark in us relish it and sit back and lap it up like a cat with a pat of stolen butter.

Taffy Thomas is one of the world’s great storytellers; with his Storyteller’s Chair and his Tale Coat and his vast collection of tales, he has travelled the world scattering wit and legend, wisdom and fun, like an old oak shedding its leaves in an autumn blow. I have shared the stage with him on many occasions and in many and various places, from the hard streets of Liverpool 8 to the kinder climes of a South Lakeland pub, and have never failed to be entranced by his stories. In this collection of Cumbrian tales there are lots more fallen oak leaves to dance in the wind and delight you. Enjoy.

PREFACE

This collection of folk tales is one to be shared and enjoyed from the page as much as when the storyteller regales his listeners. When the tales are read, standing behind will be the ghosts of all who told them before, but also within them is the spirit of the wonderful landscape. The stories and legends also evolve from the people inhabiting that landscape, from the Pagan beliefs that surrounded the tales brought by the Norsemen, which existed around these parts longer than most other places because of the remote terrain, to the many legends brought by the missionaries and the invaders who arrived later.

By dividing the book into a series of parts highlighting the themes of the stories, I hope the discovery of their delights will become more accessible and enjoyable. As I say in the book, ‘people remember their history as stories’; that’s true, but the stories also reflect the character and spirit of the people, and here in Lakeland, above all, the character and spirit of the land.

To people living so remotely and so close to nature, it is not surprising they should sense a ghost or boggle behind every bush, a fairy on every fellside or a wood sprite in every willow, oak or rowan tree. Cumbrians still tread paths known to have been trodden by Vikings, Romans and early saints. So, it is said that, although we know Hardknott as the site of a Roman fort, it was also once believed by folk to be a fairy rath – indeed, the home of Eveling, king of the fairies.

As Findler says,when referencing the thoughts of Cumberland bard Robert Anderson (born in Carlisle in 1770):

If the Lakelanders did keep the books on legendry, giants and fairies alongside the Family Bible, who knows that these humble folk did not see a closer connection between such volumes than the rest of the outside world ever realised.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As a professional storyteller who possesses the majority of the stories in this collection as part of my everyday repertoire, it is appropriate that these acknowledgements are a story in themselves: the story of my journey to this unique collection, and the story of the people who took me on that journey.

When I was the Director of legendary folk arts company Magic Lantern, living in Suffolk in the 1970s, something happened that changed my life and repertoire. A commission to work with Welfare State International, a Cumbrian arts company, sent me north where I fell in love twice. First, I met and fell in love with my future wife and muse. Secondly, I fell in love with the beauty of Lakeland, with its lakes, mountains, culture and traditions.

When I told a Suffolk farmer on my return that I was relocating to the North West permanently, he commented, ‘Well, Taffy, we never thought you would leave us, but love will draw you where gunpowder wouldn’t blast you.’ How true!

In my new life I immersed myself in the vibrant local culture; I attended the monthly Ireby ceilidhs with the Ellen Valley band, and was soon invited to contribute tales from my rich repertoire. One good story deserves another, so band member Sue Allan told me ‘The Spectre Army of Souter Fell’. Ed Mycock told me of hunt suppers and shepherds’ meets, where traditional songs and folk tales were still sung and told. At these events I learned that Cumbrians often carry their narratives in ballad, poem or monologue, usually in dialect. I have tried to represent this strand in this collection, although I would never patronise Cumbrians by faking their rich dialect in performance. Whilst I can never be Cumbrian, my children can never be anything else.

At the World’s Biggest Liar Contest in Wasdale, I heard ‘John Peel’ sung with pride by ‘Bill the Bellman’, and heard tell of the fantastic stories of Will Ritson, former landlord of the Wasdale Head Inn. I spent time with participants, including acclaimed many-times winner farmer John Graham, and legendary fell runner Joss Naylor.

I transported Ambleside huntsman Sammy Garside to the Troutbeck ‘Mayor Making’, a hunt supper, joining in the songs and telling a story or two. Skelwith Bridge character Tony Bragg took me to hound trails, making sure I didn’t lose my shirt by backing too many no-hopers.

Coppicer Walter Lloyd yarned, played the fiddle and showed me the Cumbrian traditions of forestry, using fell ponies, charcoal burning, and making Herdwick wool rope.

Even greater riches were to be found nearer home in my adoptive village of Grasmere. Joining The Grasmere Players, I discovered senior members had knowledge and talent far beyond Arsenic and Old Lace and romantic comedies. Percy Jacobs had a prodigious knowledge of local geography and geology, and Vivienne Rees was steeped in local, particularly oral, history. Vivienne’s husband, Jim, a Welshman in exile, had expansive knowledge and a memory to match. He would think nothing of stopping me in the street, and, on hearing I was heading for a performance at Carlisle Castle, would recite the first twenty verses of ‘The Ballad of Kinmont Willie’ with gusto from memory. The delight that was Joyce Withers showed me the pleasures of the Cumbrian dialect, making it comprehensible and fun.

In the summer we dressed in our best to take part in the Grasmere Rushbearing parade, and were welcomed as part of it; I was now ‘at home’.

Windermere’s Des Charnley, a guide at Windermere Steam Boat Museum until his early death from cancer told local stories monthly at my South Lakeland Storytelling Club. Des had a local repertoire that inspired me to dig deeper.

As most of these tales exist only as fragments or ‘shavings’ in the current oral tradition of the county, I have had to flesh them out with research from local history books and previous story collections. All of these are credited in my Bibliography. It is fair to say that the whole would not have come together without the support and the research of my wife Chrissy, our PA Tony Farren, and young Cumbrians – my daughter Rosie, Ellie Nelson, Ryan Walker, and illustrator Steven Gregg – I remain indebted to all. Each story is preceded by an introduction defining its journey to me, and the source. If you enjoy these tales, please visit their locations and pass them on.

Whilst all mentioned in these Acknowledgements, and others, have their fingerprints on the content and style of this collection, the whole is fondly dedicated to the memories of Joyce Withers, Jim Rees and Des Charnley.

ILLUSTRATIONS

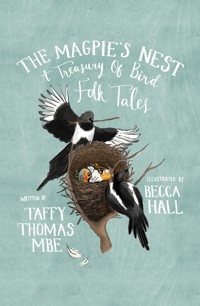

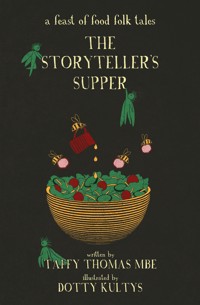

The illustrations have been drawn by young Cumbrian artist Steven Gregg.

I was born and raised in Cumbria, and am currently living in Ambleside. As a student I studied Graphic Design at Nottingham Trent University. I am now working in freelance illustration, and was delighted to be involved in the book. I grew up with many of these stories and couldn’t resist the chance to create my own illustrative interpretation of them.

Steven Gregg

The cover illustration has been created by Katherine Soutar, who has done the covers for the whole collection of the folk-tales series.

The image on the sign for the storytellers’ garden was done by John Crane, who has had a long association with the storytelling centre, providing images for its publications.

LONG MEG

Near the village of little Salkeld stands the stone circle that comprises the Neolithic monument called Long Meg and Her Daughters. Older than Stonehenge, it is completely unspoilt by modern commercialism: visitors can walk up to it and view it, and neither the resident cows nor the local land owner seem to mind.

Many years ago, in the village of Little Salkeld in the Eden Valley, there lived a woman by the name of Margaret, although folk called her Meg. Meg kept the old religion, which is to say she was a witch. She had many daughters and brought them up in the old religion. The village priest knew he had a coven of witches nearby, but didn’t interfere provided they didn’t practice their religion on the Sabbath. Likewise, Meg and her daughters respected the priest’s religion and maintained a distance.

The witches had two main annual celebration days, namely Halloween and the Summer Solstice. A problem only arose if either of these dates fell on a Saturday, for if the witches didn’t cease their activities by midnight, they would be straying onto the Lord’s Day. One summer, the priest noted that the Summer Solstice was due to fall on a Saturday. He went to Meg and pleaded with her to finish their celebrations by midnight. Meg assured him that she herself would, but that her daughters were now teenage girls and that teenage girls can be rather wilful. However, she would do her best to persuade them to conform. Knowing he could do no more, the priest returned to his church.

Meg called her daughters to her to plan the following Saturday’s Solstice celebrations, and asked that those celebrations be finished by midnight. The daughters of course complained vehemently, and the problem was not resolved. On the Saturday evening, Meg and her daughters were dancing in a field just above the village. As the hands of the clock passed 11.30 p.m., Meg approached the musicians, paid them and called for one last dance. At the end of this dance the musicians and Meg proceeded down the hill towards the village. Coming up the hill in a long, black cloak was a stranger with a fiddle under his arm. If the wind had blown this cloak aside, Meg might have noticed a cloven hoof. The stranger approached the dancers and asked if they were in need of a musician. Mischievously, Meg’s daughters paid him a bag of gold. The stranger took out his fiddle and started to play his music, as though the very hounds of hell were at his heels. And with a whoop, the daughters danced wildly in a circle. They were still dancing when the church clock struck midnight. In the church, the priest heard the sound of the party continuing and dropped to his knees in prayer. There was a flash of light and the dancers were all turned to stone, including Meg herself, who was just outside the circle, heading for home.

They do say that if you visit that circle and count the stones and twice reach the same number, the stones will come to life and chase you down the hill. On many occasions I’ve counted, but never twice reached the same number.