Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

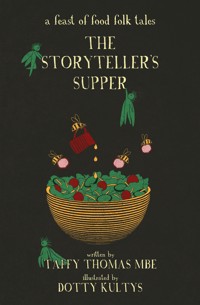

'You and me, me and you, we all bring something to the stew, From the tales we tell, to the food we've got, we all bring something to the pot.' Over the last fifty years, Taffy Thomas has shared the stage with noted Lakeland chefs, who have tickled his palate with tastings and information about dishes and ingredients, which he uses to season these magical stories, telling the oral history of food. This feast of traditional tales is spiced up with the rhymes and riddles that always enrich Taffy's work, as well as charming illustrations from artist Dotty Kultys, and will appeal to all who savour stories and food.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 193

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DEDICATION

To all the storytellers, chefs and home cooks who have fed me along the way and shown me the joy and comfort to be found in the sharing of food and stories at our tables.

Writing this collection during the pandemic of 2020, it became clear that we were all rediscovering the importance of the simple gifts we share and often overlook. Provisions, care, the joy to be found in nature, all became an invaluable part of our lockdown survival. Many people kept on working to ensure that these needs were provided, so I would also like to dedicate the book to them to remind us of a time when the sharing of our food and our stories became so important.

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Taffy Thomas MBE, 2021

Illustrations © Dotty Kultys, 2021

The right of Taffy Thomas MBE to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7509 9764 5

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Dedication

Prologue

A Welcome Toast

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Foreword

Introduction

Part I From Field & Furrow

Jack and the Boggart

The Wheat Flower

A Baker for the Fairies

The Rice Stone

Strawberry Porridge

As Good as Gold

The Golden Harp, ‘Y Delyn Aur’

Part II From Orchard & Hedgerow

Blackberry Ginny

Dividing Apples

Just Desserts

Sweet and Sour Berries

The Pear Pip

The Yazzle Tree

Part III The Storyteller’s Supper

Menu and Recipes

Part IV From Farmyard & Dairy

The Milkmaid and Her Pail

The Cheshire Cheese that Went to Heaven

Salt in the Milk

The Chicken and the Egg

Oonagh’s Special Soda Bread

Part V From the Kitchen Garden

The Queen Bee

Jack and the Magic Beans

The Parsley Queen

Soup for a Saint

A Pumpkin for the Party

The Princess of Turnips

Part VI From Sea & Shore

Why the Sea is Salty

Shrimps for a Giant

The Grasmere Gingerbread Man

Stargazey Pie

Smugglers’ Rum Butter

Davy and the King of the Fishes

Petit Fours

Epilogue

A Farewell Toast

Bibliography

PROLOGUE

Take your seat at the supper table, where we celebrate the place of food in folk tale and the place of the tale at the table. Welcome to a feast of both.

A WELCOME TOAST

A good meal

A good tale

And good company

Are all you need to merry be!TT

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Taffy Thomas has been living in the Lake District for more than forty years. He was founder of the legendary 1970s folk theatre company, Magic Lantern, which used shadow puppets and storytelling to illustrate folk tales. After surviving a major stroke in 1985, he used oral storytelling as speech therapy, which led to him finding a new career as a storyteller.

He set up the Storyteller’s Garden and Tales in Trust, the Northern Centre for Storytelling, at Church Stile in Grasmere, Cumbria; he was asked to become a patron of the Society for Storytelling, and was awarded an MBE for services to storytelling and charity in the millennium honours list.

In January 2010 he was appointed the first UK Storyteller Laureate at the British Library. He was awarded the Gold Badge, the highest honour of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, that same year. At the 2013 British Awards for Storytelling Excellence (BASE), Taffy received the award for outstanding male storyteller and also the award for outstanding storytelling performance for his piece ‘Ancestral Voices’.

More recently he has become a patron of Open Storytellers, a community arts charity supporting people with learning disabilities and autism; he is also patron of the East Anglian Storytelling Festival and of the South Lakeland Festival, Furness Traditions.

Taffy continues to tell stories and lead workshops, passing on both his skills and extensive repertoire. He is currently working on a new History Press book Storytelling for Families, to enable families to enjoy this precious art form together at home.

In 2020, while writing the manuscript for this book, his previous book The Magpie’s Nest: A Treasury of Bird Folk Tales was winner of the Literature and Poetry category of the Lakeland Book of the Year awards.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Dotty Kultys directs, writes, designs and animates stories, experimenting with seemingly unfitting styles and focusing on characters that sometimes may get overlooked. With a BA in Acting and an MA in Animation, she specialises in directing, idea generation and character performance. In recent years she has worked on a variety of projects, ranging from book illustrations, narrative poetry and song lyrics, through studio work, to animated theatre projections, music videos and short films. She is currently working freelance in Bristol.

‘When Taffy asked me to illustrate this collection of tales, I was thrilled. We’ve worked together before on animating one of his tales, “The Hunchback and the Swan”, and it was an absolute delight. What better way to join forces again than by telling tales about food! I think it’s particularly fitting that I’m illustrating this book just before Christmas. Yuletide is a time when my mum and I would spend entire evenings bustling about in the kitchen – sifting, grinding, cutting, mixing, kneading, forming, decorating – and all the while Mum would regale me with family tales, liberally sprinkling them with made-up silly rhymes. She probably doesn’t realise this, but somewhere between dicing the prunes, singing a witty ditty, and tasting the borscht to check if it needed more pepper, she instilled in me an enduring love for making food and telling stories. Thank you, Mum, for this priceless gift – and thank you, Taffy, for this wonderful opportunity to celebrate it!’

FOREWORD

Sitting around a table and enjoying a good meal is a pleasure in itself. Eating in the company of a storyteller is an even greater pleasure. Imagine the idyllic atmosphere of such a supper, where, thanks to the story unfolding, the senses are heightened and the enjoyment of the narration mingles with that of the food until it forms a whole; a unique experience in which you can no longer tell if it’s the body or the mind that is drawing comfort and sustenance from the meal.

With these happy associations of thoughts and images, I began to read the draft copy of the book that my dear friend Taffy had sent me, entrusting me with the pleasant task of providing some words of introduction.

From its first pages, The Storyteller’s Supper immerses the reader in a world of folk tales and myths. These are stories that are capable of dealing with even the most complex of themes – always handled with a lightness of touch; so light in fact that it is barely detectible. Taffy is a master of this technique. He is one of those people whom I admire enormously because they have mastered something that has been praised since the days of Ovid. This is the art of simplicity – very rare in our times, though much needed.

And with the simplicity that proceeds from the language of everyday things, these stories are our companions for a meal that is rich in different flavours and which, course by course, teaches us some important values. As an example, I would like to share the beautiful message of hope embodied by the protagonists of ‘Just Desserts’, a couple for whom resources are scarce but whom I could never call poor. Throughout the story, thanks to the care they demonstrate towards all creation, living and non-living, they show great richness and goodness of spirit; virtues that in the end will turn out to be quite rewarding. This is just a small taste of what I’m sure you’ll appreciate in the course of reading: a story that teaches the importance of humility of purpose, respect, and a sense of responsibility and community.

What makes this book really special, however, is its perspective on what food and folk stories have in common: their origin in tradition, whether cultural or oral; their sense of regionality; the very act of sharing; the presence of conviviality; and the celebration of diversity in all its forms. Taffy makes these connections by referencing the abundance of food in nature and through his understanding of dialects, popular traditions and in the details of everyday life. And if the uncertainty and frenzy of today’s society results in a certain amount of both conformity and rootlessness, reading this book leads us instead to savour the many facets of life and rediscover our identity. Today, more than ever, humanity needs voices like Taffy’s that preserve and bring to life these priceless traditions that form our cultural heritage and which are still very much part of us. This is the way to build a new pluralistic humanism that harnesses the full potential of diversity as an indispensable force for shaping our future.

So, until the moment when we can once more take our seat at the table and share the joy of a meal in the company of the people we love, I invite you to read and enjoy this wonderful book. While it may not be food for the body, it certainly offers nourishment and refreshment for the soul.

Long live storytellers; long live good food and culture that celebrates the beauty of diversity.

Happy reading!

Carlo Petrini

Founder of the global Slow Food movement

Listed in The Guardian’s 100 people who can change theworld

INTRODUCTION

I love food; I never eat anything else! To some it is merely fuel – to others it is art.

Wherever you stand on this, it is undoubtedly part of our culture.

At the Storyteller’s Supper both the stories and the food are celebrated as equal parts of our culture. At its simplest, the meal has to provide subsistence and comfort. A tale well-told can also provide subsistence to the imagination and can comfort the anxious. The full sensory experience of a meal can be savoured at the Storyteller’s Supper, where the taste of the dish is further enhanced by the story of that dish and its ingredients. The storyteller can convey the magic of food history and the dish’s journey to the table, hopefully with not too many food miles.

Many of the tales in this collection are about the pleasure of sharing food. My friend Norma Waterson once told me that her Irish grandmother always set an extra place at the table, never explaining this until Norma had grown up. Her grandmother then explained that the extra place was because ‘you never know when you are eating with an angel!’ Now that’s a pleasing ghost story.

As with my previous History Press publications I have drawn the material from the canon of European folk tales and dishes, many from oral sources. As far as my ageing memory has allowed, I have acknowledged my sources in the introduction to each tale. Whilst I am equally enthusiastic about world tales and food culture, that’s another book for another day. However, I have included a couple of tales from the Far East that proved irresistible to me. These I have respectfully reworked, making them placeless and timeless so I can comfortably tell them in my own voice. In short, I have used their bones, but not their flesh, believing the only way you can harm a folk tale is by not telling it.

Without the support of The History Press team you wouldn’t have this book in your hands. Also, without the support of my wife Chrissy this collection would never have come together and I would possibly have starved to death working on it! As it happens, if I can cook, it is because back in the 1960s a group of us lads from Yeovil Grammar School set out weekly, clutching a basket of ingredients and our aprons, to the high school for girls, where the domestic science teacher, Miss Pink, taught us to cook. Although as teenagers our motivation wasn’t solely culinary, we did return home with supper for our families in our baskets. Parents and siblings dutifully ate it.

Pondering this collection, I think of all those who have ever told me a story or fed me. Many of these are long gone and now only live in my mind as ancestral voices. Dialect stories are also included, as I have always understood the importance of regional dialect to be what the late Charles Parker called ‘the poetry of the common man’. My Somerset dialect tale draws on my memory of my mother’s and my grandfather’s voices when I listened to them on their Somerset farm. The Westmorland dialect tale from my friend, Edward Acland, draws on his memory of the voice of his grandfather. Given the roots of these tales it is a fact that, like my ingredients, they have travelled directly from field to table.

My wish is that this book will encourage us to grow or shop well, to cook well, to eat well and to listen well as we cling on to this spinning globe. As this fits in well with the aspirations of the ‘Slow Food’ movement I feel honoured that my Italian friend of many years, Carlo Petrini, the founder of this global movement, has graced these pages with a foreword. I am also delighted that Polish film animator and illustrator Dotty Kultys animates these pages with such tasty illustrations. If these and the tales feed your imagination maybe you will even set up your own Storyteller’s Supper.

Taffy Thomas

The Storyteller’s House, Ambleside 2020

Part I

FROM FIELD & FURROW

Oats and beans and barley grow

As you and I and everyone know

First the farmer sows the seed

Then he stands to take his ease

Stamps his feet and claps his hands

And turns around to view his land

Oats and beans and barley grow

As you and I and everyone know

Jack and the Boggart

Throughout these islands there are magical tales of mischievous little creatures. Variously named imps, sprites, boggles, boggarts, piskies, leprechauns, hobs or elves, they wreak havoc in the lives of ordinary folk.

Every good tale needs a hero, and Jack, not too bright and not over fond of work, is often the lad to deal with these ne’er-do-wells, tricksters or even a boggart who has pitched up on his farm. This story tells of how Jack outwitted this bothersome boggart and managed to save his precious harvest in order to ensure that his family could have a loaf of freshly baked bread each day.

Jack lived on his family farm in the north-west of England. He lived with his father, who had inherited the farm from his father, who had in turn inherited it from his father and so on, back to the days of the Doomsday Book. It was natural that when Jack’s father died peacefully one night, full of years, that his only son Jack would take over the farm.

The day after the funeral, when Jack rose early shaking himself ready for work, a boggart took up residence in the ditch at the bottom of the fifteen-acre field. Jack only discovered this when his pair of shire horses ploughed a furrow clean and straight the length of the field. When he made a big turn, lining up for a second furrow, he saw that his first furrow had been filled in … and not neatly! There on the edge of the ditch, mocking Jack, stood the boggart, hooting with laughter. Jack told the boggart that it should clear off as it was trespassing on his land. The boggart retorted that its family had made their home in that ditch for generations so he had every right to be there and would not budge. Jack told him that couldn’t be true as neither he nor any of his family had ever set eyes on any of them.

The boggart told him that all boggarts keep themselves to themselves, sleeping both day and night. This admission of laziness gave clever Jack an idea. He told the boggart that if it let him get on with his work he would give half of all his crops to it and it could then just sleep the days away. Not surprisingly, the boggart agreed to this offer.

For their first crop, Jack asked the boggart if it wanted ‘tops’ or ‘bottoms’. When it decided ‘tops’, Jack planted a field of beetroot. When the beets were harvested Jack got baskets of the delicious purple roots and the boggart only a crop of bitter leaves.

For the next crop the boggart insisted on ‘bottoms’, so clever Jack planted a field of cauliflowers. When these were harvested Jack got baskets of cream and green caulis the size of footballs and the boggart just bitter stalks and wormy roots.

The boggart, who had become increasingly angry, told Jack that the next crop had to be wheat, and that the field should be divided across the middle by a rope. Then it would have the bottom half and Jack could have the top half. Jack agreed to this and immediately started ploughing and harrowing the field. He then set about sowing wheat seeds using a seed fiddle, a box of seeds strapped to his back with a wheel and a bow like a violin bow at the bottom. As Jack walked up and down the field he fiddled the bow backwards and forwards and this turned the wheel, shooting seeds out in each direction. He then stretched a rope across the middle of the field, dividing it in half.

Having prepared the field Jack then made his way to the blacksmith’s forge with a strange request. He asked the smith to make a couple of dozen fake metal wheat stalks and paint them yellow. Jack then waited for the sun and rain to do their work. It wasn’t long before tiny green shots started to appear in the fifteen-acre field. As soon as these stalks started to ripen and turn golden, Jack took the fake metal wheat stalks and planted them among the golden wheat stalks in the boggart’s half of the field. Jack then woke the boggart in his ditch and told it that it was time to harvest. The boggart sharpened his scythe and, swinging it, set off up the field. It had only gone but fifty yards when there was a clang as the scythe blade hit a metal stalk and shattered. The boggart had to head to the blacksmith’s for a new blade. With the scythe repaired, it continued its reaping but only got another fifty yards before ‘clang!’ another ruined scythe blade. After another visit to the blacksmith, who, pleased with the trade coming his way, had mended the blade immediately, the boggart had one more attempt at harvesting the wheat when, ‘clang!’ the same thing happened.

Exasperated by this thankless task, the boggart gave up, telling Jack he was welcome to the field and its useless crops and that he had decided to leave the area for fresh fields. Jack waited to make sure the boggart had flitted before coiling up the rope and collecting the metal stalks; they had done their job.

The following day was fine. Jack sharpened his scythe and harvested the whole field. He then fixed the sheaves of wheat on his cart and took them to the miller. As he watched the mill wheel turning he knew he’d be taking home many sacks of freshly milled flour. This meant that for many weeks following, his cottage would be filled with the satisfying smell of freshly baked bread.

The Wheat Flower

I have long collected riddle tales but this tale has joined my repertoire since the publication of my Riddle in the Tale book and finds itself in this new collection. It leads beautifully into a poem gifted to me on my 70th birthday by friend and storyteller Shonaleigh. It was written by her mother, Edith Marks. I thank them both. The motifs within the story of riddles and the value of the wisdom of elders recur in many folk tales throughout the world. This version has its roots in Eastern Europe.

Before my time and before your time, but in somebody’s time, there was a cantankerous old king. Despite the fact that he had an heir in the shape of his only son who was both keen and bright, the king clung on to power, like a magnet to a piece of iron. The prince, with his youthful enthusiasm, became increasingly frustrated. The idea that the dreams and energy of young people like himself were crushed by the stubbornness of old men so grew in his mind that he vowed that as soon as he felt the weight of the crown on his head he would banish all old people from his kingdom on pain of death.

Despite the old king clinging on to life and power, eventually and inevitably the grim reaper did pay a call. The prince felt both sadness and relief as a state funeral led to his crowning. With the weight of the crown came the weight of responsibility and he wondered why he had been so keen for this moment to come. Collecting himself and his energies, he proclaimed his intent to free the young folk and allow their dreams to take flight. Every family was ordered to banish their elders on pain of death if they disobeyed. Soon down the road stretched a trail of ancient refugees, many stumbling, some with sticks or crutches. What a dismal sight!