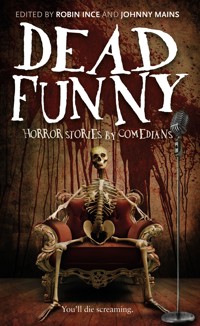

Dead Funny E-Book

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

What happens when mirth turns to murder? When the screams are not from joy, but flesh-ripping pain? Dead Funny is an audacious anthology, featuring tales of terror from some of the brightest lights in UK comedy. Award winners Robin Ince and Johnny Mains team up for this unique exploration of the relationship between comedy and horror to see if they do, as believed, make the most comfortable of bedfellows. Featuring the talents of Mitch Benn, Katy Brand, Neil Edmond, Richard Herring, Charlie Higson, Matthew Holness, Rufus Hound, Robin Ince, Phill Jupitus, Tim Key, Stewart Lee, Michael Legge, Al Murray, Sara Pascoe, Reece Shearsmith, Danielle Ward Dead Funny You'll die screaming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Dead Funny

What happens when mirth turns to murder? When the screams are not from joy, but flesh-ripping pain? Dead Funny is an audacious anthology, featuring tales of terror from some of the brightest lights in UK comedy.

Award winners Robin Ince and Johnny Mains team up for this unique exploration of the relationship between comedy and horror to see if they do, as believed, make the most comfortable of bedfellows.

Featuring the talents of

Mitch Benn, Katy Brand, Neil Edmond, Richard Herring, Charlie Higson, Matthew Holness, Rufus Hound, Robin Ince, Phill Jupitus, Tim Key, Stewart Lee, Michael Legge, Al Murray, Sara Pascoe, Reece Shearsmith and Danielle Ward

You’ll die screaming.

Robin Ince is a multi-award-winning comedian and author. His book Robin Ince’s Bad Book Club was based on his tour Bad Book Club. More recently he has toured Happiness Through Science, The Importance of Being Interested and is currently touring Robin Ince Is In And Out Of His Mind and Blooming Buzzing Confusion.

Johnny Mains is an award-winning editor, author and horror historian. He is editor of Salt’s Best British Horror series and five other anthologies, and author of two short story collections.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

The concept ofDead Funny: Horror Stories By Comedians© Johnny Mains & Clare-Louise Mains 2011, 2014

Introduction and Selection © Robin Ince and Johnny Mains,2014

Individual contributions © the contributors,2014

‘Possum’ previously published inThe New Uncanny(Comma Press, 2008) ed. Sarah Eyre and Ra Page

‘A View From A Hill’ previously published inNew Statesman(December, 2012)

The rights of Robin Ince and Johnny Mains to be identified as the editors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with Section77of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2014

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-84471-992-1 electronic

Dead Funnyis dedicated to

Rik Mayall and Robin Williams

Robin Ince would also like to dedicateDead Funnyto Nicki and Archie

Johnny Mains would also like to dedicateDead Funnyto Kevin Demant from theVault of Evilwebsite and Bob Pugh

Contents

Introduction

Foreword

Dog

A Spider Remember

The Patient

For Everyone’s Good

A View From A Hill

Most Out Of Character

Possum

For Roger

Woolboy

Halloween

Fixed

In Loving Memory Of Nerys Bag

Anthemoessa

The Dream Of Nightmares

All Warm Inside

Filthy Night

Contributor Notes

Acknowledgements

Introduction

I was luckyenough to find a sheep’s skull in a field when I was ten, and soon it was on my bedside table, with a candle stuck on it to replicate some imagined cover of a horror anthology. I was that child who hung around cemeteries, collected LPs of death and horror sound effects and Edgar Allan Poe readings by Basil Rathbone, and was told by his older sisters that, if and when he grew up, he’d become a serial killer. I became a stand-up comedian instead. On the advice of the Pope of Trash, John Waters, I have committed my hideous crimes as comedy routines rather than in actuality.

It all started with Alan Frank’s Horror Movies book. I still have it now, though stupid nine year old me cut out some of the colour plates to make into a wastepaper bin as a project at the Friday night Baptist church children’s group. It would be some time before I would see my first proper horror. At ten, I saw Vincent Price in The Pit and the Pendulum. At eleven, I was allowed to watch the black and white half of the BBC horror double bill season. I wrote to Boris Karloff’s widow and she sent me a lovely letter back.

All things horror were embraced by the outsider kids of my generation. We spent our pocket money on House of Hammer magazine and trading cards with a stick of yellow gum and images of Christopher Lee’s Dracula impaled on a cartwheel. I bought the Mayflower Book of Black Magic Stories and picked up Herbert Van Thal’s Pan Book of Horror Stories. The first I remember reading was by Dulcie Gray, an actor who specialised in playing well-bred couples with her husband Michael Denison, but I discovered that behind this prim and proper exterior was a mind that reveled in the grotesque. The outlet for being trapped in stagey, sometimes stodgy fare, was to kill and kill again on the page.

The comedians and writers I usually hang out with were usually the slightly weird kids at school, while others collected football stickers, they hung around comic shops trying to get hold of Monster Mag and imagining whole films in their heads from single stills of decapitated Shakespearians or frozen Nazis. We had nightmares, but rather than destroying us, we fed on them, and one day they’d become our day job. I still read Poe now, and I even got around to a one off, late night improvised prog rock musical with Robyn Hitchcock and a bunch of jazz musicians, mimes and opera singers, based on Guy N Smith’s killer crabs novels.

And while you are reading this book, remember that the goriest deaths will have been created while the writer was imagining their worst heckler. Interrupt at a comedy club at your peril, now you know what goes on in the minds of the stand-up.

As to the traumatic birth of this book, I ‘met’ editor Johnny Mains in 2010 through Twitter. I was due to play in Norwich, where he was then living. He asked if we could chat about the Pan Horrors after my show, which we did.

Over several beers, Johnny made less sense as the evening went on and he forgot his coat.

We met again when I came to Plymouth in 2011 with ‘Night of 400 Billion Stars’. He came to me with the idea of co-editing Dead Funny and it was something I immediately said yes to. However, Johnny and I are both hectically busy people and we never got round to working on the book until this year. But here it is. A book that we’re both extremely proud of, we’ve not had to kill any comedians during the making of it and I’d like to thank Johnny for all of his hard work.

Robin Ince

Foreword

I always thinkthat a good story becomes a truly great one that it has a smattering of black humour to it. The stories of Conrad Hill and Harry E. Turner, both authors of the infamousPan Book of Horror Stories series were able to, quite magically, mix disgusting horror and stomach ache laughter very easily.

It was during a chat about what anthology to do next with my wife when we hit upon the idea that an anthology by comedians would be a suitably quirky book. It’s certainly never been done before. The more I thought on the concept, the more I was excited by it; comedians write their own material and it can stray into very dark places at times. Why couldn’t they write short stories?

I had known Robin Ince for about a year by this time. I had commissioned a short story from both he and Charlie Higson, and what I was sent for The Screaming Book of Horror only confirmed the fact that a horror anthology, written by comedians, just might work.

So I asked Robin if he would co-edit the book with me. Robin said yes, then the work of finding a publisher began. Although interested, several publishers said no. They were impressed by the names we could bring to the book, but all said that horror anthologies didn’t sell any more. One publisher even laughed down the phone at me.

Finally, I found a publisher that was really excited by the idea, Salt. It’s another example of Indie publishers venturing into territory where the mainstream fear to tread.

And bless them, they’ve been brilliant to work with.

So here is Dead Funny. Horror stories by comedians. It’s an experiment in terror. Not all of the stories will make you laugh. Some of them might make you vomit or be scared to go outdoors after 6 p.m.

I’m so very proud of this book. It’s been a surreal experience to work on but a delight to do. Thank you to Robin Ince who is a very canny co-editor and also the authors who have written some excellent stories. I really do hope you enjoy them as much as I have.

Johnny Mains

Dog

reece shearsmith

I have neverliked dogs. I find them dirty and stupid and totally worthless. I don’t understand the mind of anyone that has a dog. How can you possibly find time to care for it? Let it stink out your home? Walk alongside it, scooping up its hot shit off the pavement and grass? ‘Let’s go for a lovely walk . . . oh, don’t forget the little plastic bag to scoop up the endless shit that this creature is going to squeeze out along the way.’ Never mind about the piss. It can piss anywhere it likes. I know that you are thinking that I sound unreasonable. People are very protective of these idiot creatures. I find it bizarre. They are of no value. I have no time for dog owners and their beasts.

I suppose, as an introduction that might be called ‘setting out my stall’, I must at this point explain my position. I am not too deluded to recognise that my views at first may sound extreme; but I must insist that you hear me out. As you will see – it all comes to bear.

From the age of about 11, summer holidays were spent with my grandparents. I would be taken on day trips to the seaside and the stately homes of the North of England. It was a curiously pious way to spend the long stretch between the summer and autumn terms of school. I found nothing odd about it, apart from, of course, the pervading sadness that sullied most of the enforced merriment. Sadness because in the time before I was fostered off to my grandparents I’d had my own two functioning parents and a super little brother who I loved very much. My brother’s name was Elliot. I knew him for ten years before he was killed and both my parents went mad with the grief of it. You’re probably thinking you have cottoned on to the gist of my tragic tale, and have leapt to the conclusion that my brother was killed by a dog. A dog attack. Mauled and bitten. But that is not what happened. Little Elliot was killed by a dog, yes – but it was ultimately far worse than had he simply been savaged by one. Elliot died of toxocariasis, the disease that hides in dog shit, blinding those that fall foul to it. Thus my brother went blind first. And being blind after having had sight is a hell that I would not wish upon anyone. Except dog owners. For it was dog owners on a day out without, I presume, a little plastic bag about them, that sealed my brother’s fate. Elliot was blinded by the disease that lives in dog faeces, and two years after he lost his sight, he was struck down and killed, having wandered sightlessly into the path of a van delivering cakes. The detail of the cake van is slightly absurd I know, but to mention Mr Kipling only seems to make it worse.

I heard the accident first. I was in the garden with my parents. Then a screech and a thud. The sound of my brother’s death. I remember hoping selfishly, as time seemed to slow down and swim around me, that it wasn’t Elliot. Not for his sake, but for mine. I would be in such trouble if he had been hurt when he was now so much my responsibility. I had been his eyes since the dog shit took his away. It’s odd, but up until his actual death, the guilt had always been ‘Who let him touch the dog shit?’, ‘How did he end up with it in his eyes?’ After this – his actual death – there could be no ambiguity about who was to blame. It was me. Ironically enough all because I took my eyes off him. When we ran outside the driver was already out of the van and trying to pull Elliot out from under the front wheels. I remember how upsetting it was to see the man tugging on his limp arms. Even then I thought it was probably wrong to be pulling on him like that, but I think the man was in shock. He was shouting that he hadn’t seen him and ‘There was no time to stop’, and even more curiously, ‘I’m not from round here’. The rest is as horrible as you might expect. Rushing and screaming and crying and misery. I hope you didn’t think this was going to be anything but nasty. There is no way of wrapping these events up nicely.

So as you can see, my childhood was ruined by a dog. It can be traced back. It is, unfortunately, that simple. The story – if I am actually even telling one (I’m not so sure that I am) – doesn’t end there. My brother and his death was one thing. But my revenge – my revenge on the lady that owned the dog, the original dog that blinded my brother – that is another thing.

It must read as unusual, I suppose, to wait so long over such a matter. I can imagine hastier people, once they had a lightning rod singled out for their rage and injustice, just kind of getting on with it. But not me. I waited. Initially I had to, as it wasn’t clear, as I have already stated, ‘Who let him touch the dog shit’. It was in months of nights alone with my brother, sat in the dark with him, to be at one with him, that I coaxed out of him the exact moment that he came into contact with the disease toxocariasis. We were able to whittle it down – over many months of talking – to an incident in our local park. Strangely enough, now without his sight, Elliot became almost bat-like with his hearing, and his sense of smell was also heightened. Doesn’t really do it for me, as far as a trade of the senses. All you really need to be able to do is see. Take smell away if you must. But in this instance, the curious amplification of Elliot’s other senses helped us triangulate and hone in on the day he fell in the excrement. The smell overwhelmed him to recall it. I could almost smell it myself. But alongside this was the voice of the owner – a woman, with a shrill high-pitched rather condescending tone – that Elliot was able to recall and ultimately, crucially, recognise again. Elliot remembered the woman berating him more than the dog. ‘Shuffling around in it like that – you’ve made an awful mess!’ As though Elliot himself were responsible for shitting in the park.

It is an awful feeling when, having done nothing wrong, you start to feel like you are being painted as the ‘baddie’. I began to feel like that after we killed the first dog. Yes, I know I didn’t mention it earlier, but it took time to find the right woman and dog responsible. We did in fact get through several others before we uncovered Mrs Lovelever. It was quite fortunate in a way, as quite by accident (and I suppose you could call them ‘accidents’) we were able to hone what we were doing, until we were quite skillful at it. Bear in mind, it was all me really, as Elliot was of little help. He could hardly be used as a ‘look out’. Basically we would sit in the park or I would orchestrate walking alongside dog walkers (after our talks I had narrowed it down to older ladies) and invariably because of his white stick they would always strike up conversation with us. It is insult to injury that the blind are so instantly pitiable. I knew people that would cry just at the sight of Elliot. A small boy, smelling his way through the world, when he should be out climbing trees, playing football or cycling down country lanes. It was a combination of all that and the tragic wearing of the blacked-out spectacles that left him looking so sad. I always found them so final. The curtain is down. Nothing to see here. No point in pretending that any light will ever get through. All boarded up. After getting the ladies chatting I would ask them about their dog as a way of getting them to talk at length (and they always would) so that Elliot with his bat-like hearing could have a good listen and decide if we were, in fact, in the company of our target. It would never take very long for Elliot to dismiss ones that were definite ‘no’s’. It was harder when he wasn’t sure. The signal for a ‘no’ was Elliot would give a cough. If he wasn’t sure he would remain silent. It used to frighten me when he stayed quiet. My heart would race in the minutes that passed, as it would become more and more possible that we had finally found the person responsible. Sometimes the women would ask Elliot if he wanted to stroke their dog. It was always a queasy moment. We decided that it was always best to say yes. It made the women feel good, like they were giving Elliot purpose for a few seconds. ‘His miserable life isn’t all that miserable today, he touched my dog for thirty seconds and it licked him.’ Pathetic.

The first time it happened, that Elliot thought we had the right woman, I nearly passed out in fear. My heart was pounding anyway because he hadn’t dismissed her with a cough. I think he was unnerved too and he let her say her goodbyes and leave before gasping, ‘I think that’s her.’ I needed it confirmed immediately.

‘Are you sure?’

‘I think so. Yes.’

When it came to the next step, it felt very much like passing through a door into something you knew would change your life forever. People in normal life don’t do what we were doing. Spending, in fact, a LOT of time doing. It was obsessional, but it felt in check because I recognised it was obsessional. When a woman was a distance away, we would wait for her to be separated from her dog, this was before they had those long ball throwers with what looks like an ice cream scoop at the end, so we relied on sticks or balls thrown by hand that would send the dogs running off into the woodland that surrounded the park. Of course it didn’t always happen so smoothly. Some never let their dog off the lead, so they were reluctantly abandoned. But it was quite an easy task to get the dog once it was in the woods and simply take it home with us via a footpath through the trees. The owners would be left calling for their mutt from the edge of the green, not realising at that point they were never going to see it again.

Now then. Killing a dog. You won’t want to hear this. We did it in the shed, and not always when my parents were out. I don’t know why. It did occur to us that there might be noise and barking etc., but I think we felt untouchable. I could always imagine a scenario of being caught, but equally imagine being able to explain it all away. The first one we killed was hard because it was the first one. In actual fact, it should have been easy as it was a very little dog; one of those that look more like a rat. It never ceases to amaze me that people spend any time on these creatures, putting red bows on their heads and stuff. Anyway. Elliot stood in the corner panting; the dog was running round in circles. I think it was excited because it was in a new place. It took some courage to even decide how I was going to kill it, and it was made worse by having to narrate everything every step of the way for Elliot’s benefit. It made it all very firm and real. I think it might have stayed more in my head, not having to say it all out loud, if you know what I mean. I pulled down a hammer, hanging from two nails on the shelf, and braced myself.

‘What have you got? What have you got?’ hissed Elliot. The first strike: I missed it and hit the floor. The dog barked and growled at my act of aggression. After that point it occurred to me I might end up bitten, so I quickly thought of something. I grabbed a hessian garden waste bag that was crumpled up in the corner and threw it over the dog. It got out from under it quickly enough, and it took several goes to get it covered and then stand on the bag either side of the dog, pinning it tight to the ground underneath. But I did it. It was then much easier to hit the bulge in the middle of my legs without feeling nearly half so sickened. It squeaked on the first hit, then kind of whistled, then stopped altogether after about twenty smacks with the hammer. I don’t know why but I started counting the blows out loud, like it was an important part of the process. As if there was a correct number I had to get to. I suppose I stopped at twenty because it was a round number. Elliot said, ‘Is it dead? What does it look like?’ and it was in his asking what it looked like that all remorse or sadness or upset for what I had just done, completely and utterly disappeared. Fuck this stupid cunt dog. My brother was blind because of it. It deserved to die. I lifted up the sack. At first I couldn’t pull it away from the mess underneath. I had hit so hard in places that the material was pushed in and out of the dog and it was mangled. I stopped bothering in the end and folded the whole thing in on itself and took it to a bin in the park. I just walked along casually, with Elliot of course, and put the whole lot in the rubbish like it was nothing.

The realisation that there were flaws in our plan came very quickly. On our way home from the park, after the first killing, we passed a woman talking to a sandy-coloured Labrador and Elliot whispered to me, ‘Oh God, I think that’s her.’ And thus it began. A spate of dog killings. Each one satisfying in the moment,, but lasting only as long as it took to walk past another possible candidate. Curiously, I never got annoyed about it. Elliot was blind, how was he supposed to know? Ultimately we realised this was going to be a little bit trial and error. Once that was understood, it was actually – and I don’t mean for this to sound ghoulish – quite fun. Aside from the fact they were all mistakes in regard to them being the wrong dogs, in our eyes (ha) they weren’t – because they were still dogs. We had moved beyond our own feeble search for justice, and our punishment had become far more encompassing. This was about the eradication of a much bigger problem. And so it followed that we began experimenting with different ways to kill dogs. I remember one spate of killings that were purely about how quickly and succinctly it could be done. Finding that ‘sweet spot’ that, with one blow, would kill it instantly. (I had read they kill pigs this way) I never managed it with one, but I think I did do it in three once. Anyway. We once tried to drown one, but it didn’t work, it kept getting out and splashed and thrashed most of the water away. And a paddling pool is not the best receptacle to drown an angry dog in fighting for its life. We needed a tin bath really.

Other methods included cutting all the legs off first, then finally the head. This could only be attempted with the more ratty dogs as I previously stated. We tried injecting one using an old icing sugar pipe. Didn’t really work. Annoyed, I think we blow torched it with an old aerosol can. Stank the shed out though.

I can’t remember when we decided that we had been getting it all wrong and it was the owners of the dogs who were actually to blame and not the dogs themselves. (The irony of this part is that some of you will be less appalled at our killing of the old women than the killing of their stupid fucking dogs.) I do know when it was, actually: we were sat watching That’s Life with Mum and Dad. Cyril had just done a funny limerick, and there was one of the many awkward segues into something more serious from Esther, when she turned her attention (yet again) to some child abuse or other, as was often the way. It was always shocking, but made worse because only moments before we had seen one of the team burst into song at a garden centre and grab a passer-by and made her join in. What I got from this report, which was about cruelty to animals, was that people who owned the animals seemed to be getting the blame. What I didn’t get from the report was any pang of guilt that I had been cruel to animals. It never even occurred to me. It just made me shift focus from the animals to the people.

The first old woman (Elliot assured me she was the one) was very sweet really, and accompanied us back to our house without any fuss. I told her that poor, blind Elliot wasn’t feeling very well and would she mind seeing that we got home alright. As I have said, people go a little bit weird around blind people – silly really since they are the one set of people that can’t see how you are (or are not) behaving, but she readily said of course she would help. Her dog was big. I was secretly pleased we were going to kill her and not it. I wouldn’t have known where to begin, but as we walked along I thought, she would easily fit into two rubbish bags. We got to our house and I told her, if she wouldn’t mind, to put her dog in the shed, just out of the way, as our mum was allergic. She said of course and once she was in there I grabbed the dog hammer (did I mention it became known as the dog hammer?) and smacked her on the head with it. She was puzzled at first and sort of bent double. This gave me a nice pop at the back of her head which I hit with the claw part and wrenched free, pulling off part of her scalp and a bit of skull, I thought. Anyway, she was easy and it all went well. The annoying part was the ‘get rid’, which took ages as despite being little, she was still bigger than what I’d been used to. I don’t remember how many more we killed. I think probably about eleven or twelve. They all merge into one when I think back. There’s the odd funny detail: one of them, I remember, her false teeth flew out when I hit her head. I was laughing and Elliot was saying, ‘What? What’s funny about it?’ It was ages before I could tell him, I was laughing so much. Another one tried, quite quickly after the first blow, to grab me; she was quite strong. I hit her again and then, as she burbled on the floor, I cut her feet off with a saw. I chopped them off with her shoes still on, but I concede it was done in spite because she had actually managed to scratch me. (I told my mum that I must have done it playing. She didn’t care.) I don’t know why I did this, but because a lot of them were old, they nearly all wore glasses and so I began keeping them. I had about eight pairs when we finally met Mrs Lovelever.