7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Contains:

- Horst Wessel: Life and Death, by Erwin Reitmann

- SA Sturmführer Horst Wessel: A Portrait of a Life of Sacrifice, by Fritz Daum

- Horst Wessel: Through Storm and Struggle to Immortality, by Max Kullak

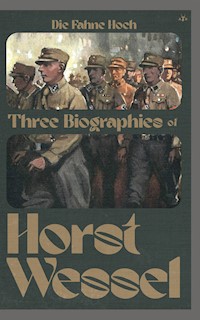

The namesake of this book—“Die Fahne Hoch,” or “Raise the Flag”—is a song written by Horst Wessel as a fighting song for the SA. After his martyrdom, it was adopted as the official anthem of the NSDAP and later as the national anthem of the Third Reich itself, as the Horst-Wessel-Lied. The three biographies in this collection are not so much dry factual recitations as they are passionate eulogies for a young man who laid down his life for his country, driven by idealism and a fanatical love for his people. Horst Wessel’s stature as an icon of the Third Reich achieved such heights that the legend of his life and death crosses into the territory of founding mythology for National Socialist Germany.

Horst Wessel served as an example to the youth of a defeated and desperate nation, a shining illustration of the value of courage and devotion, and proof that noble deeds often far outlive one’s own life and even the original circumstances in which they were made. Antelope Hill is proud to bring these short biographies together in one collection, Die Fahne Hoch, newly translated for the English reader.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Die Fahne Hoch: Three Biographies of Horst Wessel

Die Fahne Hoch Three Biographies of Horst Wessel

Horst Wessel: Life and Death

By Erwin Reitmann

SA Sturmführer Horst Wessel: A Portrait of a Life of Sacrifice

By Fritz Daum

Horst Wessel: Through Storm and Struggle to Immortality

By Max Kullak

TRANSLATED BY KLOKKE VAN AELST

A N T E L O P E ii H I L L ii P U B L I S H I N G

Translation Copyright © 2022 Antelope Hill Publishing

First printing 2022.

The original content of these works is in the public domain. Three separate works have been translated and combined into this collection:

Horst Wessel: Life and Death

by Erwin Reitmann, originally published in German as

Horst Wessel—Leben und Sterben

by Traditions-Verlag Kolf & Co., Berlin, 1933.

SA Sturmführer Horst Wessel: A Portrait of a Life of Sacrifice

by Fritz Daum, originally published in German as

SA.-Sturmführer Horst Wessel—Ein Lebensbild von Opfertreue

by Enßlin & Laiblins Verlagsbuchhandlung, Reutlingen, 1933.

Horst Wessel: Through Storm and Struggle to Immortality

by Max Kullak, originally published in German as

Horst Wessel—Durch Sturm und Kampf zur Unsterblichkeit

by Langenfalza, Verlag von Julius Beltz, Berlin and Leipzig, 1934.

Translated by Klokke van Aelst, 2022.

Cover design by Swifty. Painting by Karl Mühlmeister appeared in SA.-Sturmführer Horst Wessel—Ein Lebensbild von Opfertreue.

Edited by Tom Simpson.

Formatted by Margaret Bauer.

Antelope Hill Publishing

antelopehillpublishing.com

Paperback ISBN-13:978-1-956887-20-4

EPUB ISBN-13: 978-1-956887-21-1

Contents

Introduction

Horst Wessel: Life and Death

Preface

Horst Wessel: A Portrait of His Life

Songs by Horst Wessel

Wir Tragen an Unserm Braunen Kleid

Edelweißlied

Horst-Wessel-Lied

Remembering Horst Wessel

The New Sturmführer

The Storm Evening Meetings

Nobody Wants Us

The Shawm Band

How to Break the Red Terror

The Orator

The SA Enters the Fischerkietz for the First Time

Nuremberg

We Celebrate the Constitution

We Push Our Way Through

What Is Horst Wessel to Us?

Horst Wessel’s Death: Shared by Peter Engelmann

The Report of a Nurse at the Horst Wessel Hospital

The Account of the Doctor in the Horst Wessel Hospital

Photos

SA Sturmführer Horst Wessel: A Portrait of a Life of Sacrifice

The Young Horst Wessel

Introduction

Horst Wessel

Defending Oneself Is a Right and a Duty

Horst Finds the Way

The Dedicated SA Fighter

In Red Berlin

Hard Work

Storm 5

Horst Wessel the Poet

The Winds of War Blow through the Red Districts

Storm 5 Gets a Shawm Band

The Trip to Pomerania

Publicity Trip to Frankfurt on the Oder

Raise the Flags

The Terror of the East

Horst Wessel the Worker

Farewell to the Old Life

Warned Again

Dark Days Are Dawning

Sickness and Murderous Thugs Attack Horst Wessel

The Hero’s Last Stand

Here Mournful Love; There Poisonous Hatred

Never Forget This, German Youth

The Flags Are Lowered

Horst Wessel: Through Storm and Struggle to Immortality

Admittance to the Sturmabteilung

National Socialism

SA Service

Publicity Trip to Pasewalk

Among the People

The Sturmführer

Party Congress in Nuremberg 1929

Struggle and Sorrow

Rotmord

Lower the Flags

Immortality

Introduction

Horst Wessel: a man whose name is still known today, more than ninety years after his passing. He died a martyr for National Socialism, as Dr. Joseph Goebbels described him, and became the face of an entire organization and the symbol of a movement the likes of which the world had never witnessed before. Although the Berlin Sturmführer enjoyed only local fame during his lifetime, after his death his name became the common knowledge of every German. Streets, squares, hospitals, and monuments were devoted to him. One of his songs, known as the “Horst-Wessel-Lied,” would even become the party anthem of the NSDAP.

Horst Wessel: an interesting figure to examine both from a historical as well as a meta-political point of view. One would be surprised that, despite his fame, practically no biographical texts were written about him after the Second World War. Daniel Siemens seems to be the only exception in this regard. In his book, Horst Wessel: Tod und Verklärung eines Nationalsozialisten, originally published in Germany in 2009 and translated in 2013 under the title The Making of a Nazi Hero—The Murder and Myth of Horst Wessel, he presents the most complete biographical account of the young man to date. When it comes to quality translations of original German biographies published in the years after Wessel’s death, however, one could only look in vain—until now. This compendium brings together three works from the 1930s, translated for the first time for an English-speaking audience:

1. Horst Wessel—Leben und Sterben by Erwin Reitmann, originally published in 1933 by Traditions-Verlag Kolf & Co. in Berlin.

2. SA.-Sturmführer Horst Wessel—Ein Lebensbild von Opfertreue by Fritz Daum, originally published in 1933 by Enßlin & Laiblins Verlagsbuchhandlung in Reutlingen.

3. Horst Wessel—Durch Sturm und Kampf zur Unsterblichkeit by Max Kullak, originally published in 1934 by Langenfalza, Verlag von Julius Beltz in Berlin and Leipzig.

Erwin Reitmann was a fellow combatant of Horst Wessel. One can therefore assume that he knew Wessel very well and thus knew what he was writing about. Nevertheless, Reitmann’s biography feels mostly like propaganda, which is to say, that it feels like the least-subtle propaganda compared to the other two works. This is somewhat ironic when one reads the purpose of the book on the first page: “It is intended to paint a clear and unembellished picture of the unique personality of Horst Wessel.”

Fritz Daum’s biography seems to be the most complete. It is also by far the longest of the three and, like Reitmann’s, the amount of propagandism is very high, almost equaling the latter. The subtitle of this book shows that the specific target audience was the German youth. However, this does not mean that the language used is childish in any way. Daum tries to set as perfect an example as possible for the young readers, in which he succeeds by means of the narrative style of the book.

Max Kullak brings us the shortest book of the three. Like Erwin Reitmann, Kullak was a member of the SA, as shown by the dedication at the beginning of the book. Whether he was acquainted with Wessel is not known. Despite the brevity of this biography, the author manages to give a unique view on several events. As an additional bonus many songs that are included in this book. In the translation of both this and the other two books, the original German lyrics have been preserved alongside the English translation. Not providing the original lyrics would not do justice to the splendor of the German language and it would deprive the reader of the chance to read these verses as they were once sung in real life.

Translating three books that describe the life of one and the same person—although in different ways—has some advantages. Each author places different touches in his own work. Where one book only mentions a person or an event by name, for example, the other book expands on it at length. For example, Reitmann mentions the recruitment drive to Pasewalk in a single sentence, whereas Daum and Kullak each devote a separate chapter to it. Conversely, Kullak pays little attention to the death of Werner Wessel, Horst’s younger brother, while Reitmann and certainly Daum successfully use the boy’s death to portray Horst as a true hero. The same can be said of Erna Jänicke, Horst’s alleged girlfriend, whom he saved from the hands of the Red Front.1 Reitmann mentions her by name only once and Kullak does not even mention her at all. In Daum’s case, on the other hand, Jänicke actually has an important supporting role. A possible explanation for the omission of the existence of this lady will be discussed below. Numerous other examples can be given besides these, including the incidents involving the shawm band and the entry into the Fischerkietz.

A second advantage can be directly linked to this. By reading the three parts of this compendium side-by-side, the reader not only obtains a picture of the life of Horst Wessel himself, but also, to a certain extent, a picture of Horst’s family and friends. For example, both Kullak and Daum tell the story of Sturmführer Albert Sprengel and how he came to be nicknamed “Barrikadenalbert.” Werner and Inge Wessel, Richard Fiedler, and Dr. Joseph Goebbels are also recurring characters.

Because these three books deal with a specific time and place, terms and names are used which are not a part of today’s general knowledge. Especially for a non-German speaking audience, names like Reichsbanner, Corps Normannia, and the Bismarck League, to name a few, will sound strange. However, from explicit and implicit explanations present in the books, the reader will be able to determine the meaning and significance of these organizations. Footnotes have been added to give context and to enhance the experience of the reader.

In a more general way, the reader also gets a good idea of what life in Berlin was like in the 1920s. Propaganda trips to the villages around Berlin, political speeches in smoke-filled pubs and conference halls, large-scale street and bar fights between individuals of various political factions, evenings filled with the singing of new storm songs, nights in prison filled with the singing of those same storm songs, bloody faces, broken bones, bruised ribs and, yes, bullet holes; it was all part of the daily life of many young people in those days.

This brings us to a third advantage. By placing three different reports side-by-side and reading them carefully, some interesting discrepancies emerge. The most striking difference is found in the last moments before the attempt on Horst Wessel’s life. In Kullak we read that Wessel, when he hears knocking on the door exclaims, “Come in, Albert.” In Reitmann’s case we read another name: “Come in, Richard.” The fact is that we do not know which name he called out. However, both names are possibilities since both were good comrades of Wessel. After all, Albert here refers to Albert Sprengel and Richard to Richard Fiedler. In another place we read about the limited funeral procession at Horst Wessel’s funeral. Reitmann writes that ten wagons were allowed to follow the hearse. In the case of Kullak and Daum, there were only seven.

The above discrepancies are ultimately only minor details. However, they make it clear that the reader should not necessarily believe every detail in these books. This is especially true for every sentence that is placed between quotation marks. It seems almost impossible that the three authors knew exactly what Wessel said during his conversations as a child. Equally impossible seem the lively conversations with the nurse after the assault on his life that Reitmann and Daum write about. These doubts are reinforced by the official description of his injuries: his tongue, uvula, and palate would have been largely blown away by the impact of the bullet. Elsewhere we read about Mensur, a ritual fencing match customary in certain student associations in the German regions. According to Daum, Wessel would have trained this with his left arm after hurting his right arm. If we are to believe Walter Reinhart, a fellow Corps member of Wessel’s, Horst would have been able to do anything but master the art, even after many training sessions. The author of this introduction, having held a Mensur sword—a Mensurschläger—in his hands on several occasions in Germany, can also confirm that this is not something that can be mastered easily, let alone with the left arm. Finally, figures also seem somewhat embellished. Thousands are said to have attended the funerals of both Horst and Werner. Is it possible? Yes. Is it credible? A little less so.

Regarding quotations attributed to Horst Wessel, there are also several exact similarities between the different books. The best example is again found in Kullak and Reitmann. When Horst is present at a meeting of the Social Democratic Party, he says, according to both authors, “Ich bin zwar noch sehr jung, aber sehen Sie, gerade die Jugend hat ja letzten Endes unter den heutigen Zuständen am meisten zu leiden.”2 Did both authors have access to the same source? Did Kullak, who published his book in 1934, have access to the work of Reitmann, whose book had appeared one year prior? We have no way of knowing. One should not forget that a biography by Hanns Heinz Ewers was also published in 1932. The same question can be asked: did Kullak, Reitmann and Daum have access to Ewers’ work? For the time being, an English translation of this last book is still lacking; an answer to this last question is therefore also pending.

Finally, attention can be drawn to the details that the authors leave out, whether intentionally or not. For example, we read that Wessel gave up his law studies to become a worker. In reality, he left university after repeatedly getting bad grades. Then, there is the elephant in the room: Erna Jänicke. Above it was mentioned that Kullak does not mention this lady and that Reitmann mentions her only once. This is somewhat bizarre, given that Jänicke was present in the apartment at the time of the assault. She is mentioned frequently in Daum’s book, and both he and Reitmann refer to her as the girl who was saved by Horst from the clutches of communism. What all three authors forget to mention is that Jänicke was a former prostitute. Daum, however, seems to make the allusion, albeit very subtly.

The communist magazines went one step further and called Wessel her pimp, murdered because he had stolen her from the pimp Ali Höhler, who is better known as Wessel’s murderer. That this is not explicitly written down should not, of course, be surprising. It would merely give a bad image: a pimp as a role model for the new youth. That Wessel was Jänicke’s pimp is anything but an established fact, as corroborated by the court testimonies by both Jänicke and Höhler. They only knew each other by name, and further relations did not exist.

It is by no means the intention here to depict Horst Wessel as a scoundrel, nor to label the three authors as liars. Let it be clear that these three books are propaganda. The boundary between biography and hagiography is not absolute in this case. Also, the line between fantasy and reality is not always clear. However, this does not take away from the fact that Horst Wessel did achieve certain things as a Sturmführer. The story of the shawm band is a good example. From higher-up, the establishment of a band was forbidden. Wessel was the first to establish one anyway, with great success in the field of propaganda as a result. The fact that Wessel was the most requested speaker for speeches after Gauleiter Joseph Goebbels, as both Reitmann and Kullak attest, also corresponds with reality. And although he did not write the melody himself, the “Horst-Wessel-Lied” is one of his creations: a creation that is still known almost a century later.

Each of these books contributes to the myth of Horst Wessel: a young man, inspired by the ideals of the Führer, Adolf Hitler, and determined to put them into practice. In certain respects, Hitler and Wessel have some things in common. Both lost their father at a very young age, and both grew up in relatively turbulent times. However, this is also where the biggest difference between them lies. Horst Wessel, the son of a pastor, may have grown up in Weimar Germany, but the years of learning and suffering that the Führer endured in Vienna are foreign to him, not to mention the war years at the battlefront in Flanders. A leader born from among the people Wessel was not. The three authors know this and act appropriately to make Wessel the hero he needed to be. The focus is not on his experiences as a proletarian, as is the case for Hitler in Mein Kampf, but on his experiences as a well-to-do citizen in relation to the proletariat. Wessel is given a double task: he first had to become one of the people before uniting them.

Answering the question of who Horst Wessel was as a person is a research question for historians. From a meta-political perspective, this question is less relevant. Here it is not Horst Wessel as a person, but Horst Wessel as an idea that is of importance. It is unimportant which facts correspond to reality and which facts were embellished for propagandistic purposes. It is about an idea, an archetype. The new youth was in need of an example in the fight for a new Germany. Young, heroic, determined, resilient, faithful to the ideals; a true National Socialist. This is the role model the youth needed, and this role model bears the name Horst Wessel.

Klokke van Aelst

April 20th, 2022

Horst Wessel: Life and Death

ERWIN REITMANN

This book is intended to help faithfully preserve the memory of the martyr of the National Socialist Freedom Movement.

It is intended to paint a clear and unembellished picture of the unique personality of Horst Wessel. And above all, it should allow the greatness and purity of our worldview to be measured by the life, struggles, and death of the dead hero.

PREFACE

As an old comrade-in-arms of Horst Wessel, I felt called upon and obliged to erect a memorial stone in this form to my dead comrade, the hero of the National Socialist movement.

I speak here as one of the many who were allowed to fight for Germany’s liberation in Horst Wessel’s storm. These leaves are intended to express the gratitude of thousands of SA men who today faithfully guard the name and legacy of this great martyr.

May this book be a source of spiritual strength for the reader, from which he can draw when his strength begins to fade in the fight for Germany.

Erwin Reitmann

Berlin, July 1932

HORST WESSEL: A PORTRAIT OF HIS LIFE

Kamerad Wessel

Hanz Flut

Kamerad Wessel, wir trauern um dich . . .

Unsere Augen verlernten das Weinen;

Unsere Augen wollten Versteinen,

Da uns das Leuchten der deinen verblich—

Kamerad Wessel, wir trauern um dich!

Kamerad Wessel, wir ehren dich . . .

Tief zur Erde die Fahnen wir senken;

Hoch nach Walhall die Blicke wir lenken,

Schaudernd, als wenn ein Adler entwich—

Kamerad Wessel, wir ehren dich!

Kamerad Wessel, wir denken an dich . . .

Wenn für Deutschlands Zukunft wir streiten,

Soll dein heldischer Geist uns begleiten

Brausend wie Lenzwind, der wild uns umstrich—

Kamerad Wessel, wir denken an dich!

Kamerad Wessel, wir rächen dich . . .

Schwelend genährt von Elend und Schmerzen;

Bricht einst der Haß aus gemarterten Herzen,

Lodernde Flamme, die nimmer verblich—

Kamerad Wessel, wir rächen dich!

Comrade Wessel

Hanz Flut

Comrade Wessel, we mourn you . . .

Our eyes have forgotten how to cry;

Our eyes wanted to fade away,

As we lost the glow of yours—

Comrade Wessel, we mourn you!

Comrade Wessel, we honor you . . .

Low to the ground we lower our flags;

High to Valhalla our gazes we direct,

Shivering as if an eagle had taken flight -

Comrade Wessel, we honor you!

Comrade Wessel, we think of you . . .

When we fight for Germany’s future

Let your heroic spirit accompany us

As fierce as the breeze that blew around us—

Comrade Wessel, we think of you!

Comrade Wessel, we will avenge you . . .

Smoldering, nourished by misery and pain;

Once hatred breaks out of tortured hearts,

A blazing flame that never faded away

Comrade Wessel, we avenge you!

“Germany must live, even if we must die!”

In the present age of decline of all moral values, of flattening of character and dulling of the spirit, which has spread particularly strongly among young people thanks to a certain system, the name of Horst Wessel illuminates the dark present like a ray of light. Horst Wessel’s life and death must serve as a beacon to the world around us. Horst Wessel—student and worker! The new German man who dedicated his whole life to the fight for freedom.

“Nothing for myself—everything for Germany” was not just a phrase for him. He always proved that he was serious about it.

Horst Wessel’s holy blood-sacrifice was a seed on the thorny path to German freedom that has blossomed in many ways. Many have gone before him on the blood-soaked path, and many, many, will follow him.

The great, young deceased showed thousands of despairing fellow Germans that there are still ideals for which German people lay down their lives. Under the radiant swastika flags a spiritual type has formed, the most beautiful and glorious personification of which is Horst Wessel.

In the middle of the Westphalian countryside by the mighty Teutoburg Forest, Horst Wessel was born in Bielefeld on October 9th, 1907 as the son of the pastor Dr. Ludwig Wessel. He was the first sprout to come out of a happy marriage. Westphalia has tough soil and equally tough people. Westphalians are people rooted in the soil, as Hermann Löns described them.

Until his sixth year, little Horst spent an untroubled youth in Mülheim upon the Ruhr, in the land of coal mines and pits. His father worked here as a pastor, but was called to the famous St. Nikolai Church in Berlin in 1913, from whose chapel the hymn writer Paul Gerhardt had once preached.

Close to the St. Nikolai Church, on the border of Old Berlin and the busy hustle and bustle of the city center, lies the Jüdenstraße.3 Horst spent his youth here in house number 51/52. The adjoining hidden streets and alleys always offered the best opportunity for cheerful play. Many a time he would have heard the beautiful chimes of the parochial church in the side street, which trembled through the quiet alleys and streets every half hour.

When the World War broke out in 1914, his father joined the German army as its first volunteer chaplain. As a government priest, he served the Fatherland first in Belgium, then in Kaunas at the headquarters of Field Marshal von Hindenburg.

Horst had a sister named Ingeborg and a brother named Werner. Horst Wessel and his brother Werner were brothers through thick and thin. They could not be separated from each other. One did not leave the other. Although the two brothers got along well, they were very different in character. Werner Wessel, who in contrast to Horst was more of a romantic, tried to emulate his brother in every way. After enjoying traveling for a long time and being completely devoted to the subject, he later found his way to National Socialism and exchanged his traveling coat for the brown uniform.

Horst also enjoyed hiking at first, but very early on he became involved in politics. He was a level-headed, realistic thinker who was well ahead for his age. At school he was the “hero” of the class and, as his great talent allowed him to follow along with ease, he could get away with jokes that made the whole class laugh. He was the ringleader who cooked up many a prank with his classmates. Once the teacher gave the pupils the task of writing down their political opinion in an essay. Since the matter could be done anonymously, Horst was on-board in no time and wrote an essay that pleased the teacher to no end.

Horst Wessel attended the Humanist Gymnasium, graduated from high school at the age of eighteen and studied law. He joined the Kösener Corps Normannia. After some time, he went to Vienna and became a member of the Alemannia Corps there. It was then that Horst’s student days had begun, but not those preoccupied with beer and wine. He had decided on a different worldview. As a young man he had already joined the political front—also a sign of the spiritual need of our youth, which thirsts for freedom like no other generation has.

Horst Wessel’s tremendous temperament, his love for his fatherland, and his ardent idealism broke the shackles of a rich bourgeois life. He did not find what he was looking for in the Bismarckbund,4 of which he was a member at first. But even then, as later on, it became clear that, like a magnet, he attracted the best forces to himself and immediately became the leader and spokesman of the opposition. He instinctively realized that the Bismarckbund was not an association of revolutionary youth. The leadership had grown old, and the lack of a worldview meant that the best people soon left. Horst joined because he knew of no better association. After some time, however, he found his way to the Wiking, and here he believed he had found the right thing. He was completely committed to the cause. He worked day and night. Everywhere he campaigned and pushed forward. He himself once wrote, “School and home fell into insignificance in comparison [to politics].”

The struggle for the political ideal was more important to him than anything else. His innate talent as a leader soon put him in a leading position in this military association as well. He could not do enough for his people. What he demanded of himself as a matter of principle, he believed he could also demand of others. It was simply incomprehensible to him how people did not give it their all. This is the only way to understand what he once wrote: “As soon as I had a break, mostly during the holidays, the comradeship also broke down completely. You had to work on people continuously, otherwise they would soon give up. Strange, really, because in and of itself an idea that doesn’t drive even the followers to work together is worth nothing.”

Through the Wiking, Horst also joined the Black Reichswehr and received a brief military training.5 His mother tells of how Horst left one day and she never heard from him again. After six weeks, she finally received the news from her son that he had been trained in the Black Reichswehr—instead of enjoying the summer holiday.

Even in moments like these, Horst Wessel’s entrepreneurial spirit and boldness were evident.

His affiliation with the Wiking, the so-called Organization Consul (O.C.), did not last too long.

All the idealism and self-sacrifice he had mustered for this military organization had been uselessly squandered. The surrender of Ehrhardt had left him, like so many other comrades, severely disappointed and embittered. Horst withdrew from politics, but could not bear to stand on the sidelines in the fight for Germany’s rebirth for long.

In the autumn of 1926 Horst joined the National Socialists, not out of recognition, but out of disappointment, as he himself wrote. Here he finally found what he had longed for all these years and what he had aspired to with all his heart: a greater ideal.

With a restless soul, he had previously been wandering between worlds. Now he had finally found the path to inner satisfaction. He immersed himself with all thoroughness in the teachings of the National Socialist worldview and thoroughly re-educated himself in all fields. He had always been an ardent nationalist, but now he also became a socialist, without which there can be no genuine nationalism. Therefore, Horst became a socialist as much out of instinct as out of reason! The love for his impoverished fellow Germans—social justice at any price—had long been glowing in his breast as a warning spark that never went out. The realization now kindled this spark into a soaring flame. Later, as a speaker and Sturmführer, one could often enough observe his passionate, ruthless, advocacy for the oppressed, downtrodden workers. It was characteristic that he felt most at ease in the company of modest people. For God’s sake, no arrogance! How he hated those elements of the bourgeoisie who looked down on the workers in their overalls. He confronted these guilt-ridden pests with bitter mockery and sublime irony. It is also thanks to Horst Wessel’s radical attitude that he later, as a Sturmführer, pulled so many people out of the Marxist front.

Wessel’s first activity within the party began in the SA, when he went to Pasewalk and Kottbus. In January of 1928 he went to Vienna and stayed there until July. The Berlin District Leader, Dr. Goebbels, gave him the task of studying the structure and working methods of the Hitler Youth in Vienna. This activity proved immensely beneficial. He often told his co-workers that he had learned a great deal from the Vienna Hitler Youth, which he then applied to the SA. When he returned to Berlin from Vienna, he first took over the post of head of a street cell in the Alexanderplatz section. Here he did valuable groundwork. He formed a good corps of functionaries through evening training sessions.

One evening Horst Wessel found himself standing at the lectern in the meeting hall and spoke. Horst had suddenly become a speaker. How much more he could gain from this activity! He must have restored the faith in Germany of hundreds, even thousands, of people during his many meetings. Who was more suited to be a speaker than he, with his passion, his idealism, his quick wit, and his oratory skills? Soon word spread everywhere. He was requested in Berlin and the Brandenburg region. He was the second-busiest speaker after Dr. Goebbels. It was a tactic of Horst Wessel’s to declare right at the beginning of his speech: “I may still be very young, but you see, it is precisely the youth who ultimately have to suffer most innocently from today’s state of affairs.” With this tactic, he took the wind out of the sails of old, crusty opponents right from the start.

In the meantime, Horst Wessel’s great abilities had been discovered and he was now the center of attention. He was offered the post of Sturmführer on several occasions. Too busy with his work as a speaker, he declined several times. But when he was called to join Troop 34 in Friedrichshain on May 1st, 1929, he accepted and in no time at all built up a storm in this district of strong communist resistance that had no equal in Berlin.

Storm 5 soon achieved a certain notoriety. “Respected by friends; feared by the enemy” very quickly became a reality. Day and night Horst Wessel was on the move, neglecting all else. The storm grew from day to day in an almost frightening way. How did this happen? Horst Wessel had soon realized that there were still a great many idealists in the Marxist camp, and his whole struggle was directed towards winning over these valuable forces. It is to Horst Wessel’s great credit that he began the struggle for one of Berlin’s communist strongholds, the eastern part of Berlin, with a death-defying, proportionally small group. The methods and the nature of the struggle were ultimately decisive. The boldness with which he drove the movement forward at first caused a paralyzing astonishment in his opponents, which then very soon gave way to bloodthirsty revenge. All the plans of the great struggle were organically underpinned. We worked according to a certain system. First, we provoked the enemy through marches and similar actions. In this way we achieved an engagement from the local opponent with us, which they did well enough. Then it was not long before the first people from the Red Front appeared at our rallies. A not insignificant number of them did not come out of recognition, but were attracted by the personality of Horst Wessel. Here the process of transformation orchestrated by Horst Wessel started. Since the Führer usually always gathers people of good character around him, it is not surprising that a crowd of bold people soon gathered around Wessel. They came from all quarters and wanted to join in. Like a magnet, Wessel drew people to him. Through struggle, leader and followers were bound together ever more tightly. A wonderful fighting community developed. The people went through fire for their Horst, and he himself was attached to his people with all of his heart. Whenever Horst Wessel was together with his comrades, he made use of their language and expressions to the utmost. The whole appearance immediately revealed the outstanding leader, but not the academic! It was no wonder that it was precisely the humblest people from the proletarian class who felt attracted to him! They talked to him as if he were their best friend, and yet no one dared to challenge his authority. That Horst was the leader was so self-evident to everyone, it simply had to be, and everyone was proud of their leader. It is easy to understand that there were not too many intellectual know-it-alls in this circle.

Wessel detested narrow-mindedness; modesty and straightforwardness suited him. He also did not fail to dress well. He preferred to wear bear boots, breeches, and a waistcoat.

Horst had a healthy sense of humor, and we were to experience his brightness and quick wit many more times in the future.

You could have taken him for a real Berliner by the whole of his character and behavior. Horst didn’t let anything happen to his comrades, and if he was in the right, he defended his position relentlessly to the highest degree.

In order to fully understand the working class, in order to connect with it more and more, he worked as a student at a construction site. Here he got to know the soul of the worker down to the deepest depths, but here he also had to put up with the terror and nastiness of the Marxists. Being a student, Horst was always in a position to lead a comfortable life, and yet he did not. He was not afraid to swing a hammer, carry stones, or shovel sand like they did. Socialism, the love for the fellow countrymen, was deeply ingrained in him. He tried to get closer and closer to his comrades. He renounced all material goods. He proved to them that he was their leader, but as a human being he lived just as frugally as they did.

Entirely on his own, he made his way through life.

Horst had dearly earned the trust of his comrades. Even the lowest-ranking SA member had the greatest trust in him. Only in this way was it possible for Wessel to do the most fantastic, daring things with his comrades. He could rely on his troops completely. Horst was the type of political soldier, a role model for his people in the truest sense of the word. He often undertook the most daring actions with his storm. On the storm evening meetings, however, he tried with all of his might to implant the teachings of National Socialism in the hearts of his people.

His talent as a speaker and his knowledge served him well here. These were not dull evenings of instruction, for the way Horst educated his people to become National Socialists kept everyone engaged.

Due to the constant growth of the storm, which some comrades observed with increasing concern, we eventually had to hold the storm evening meetings in conference venues. In time, however, the constant influx from the Marxist camp also brought in subversive elements who tried to sow discord between the leader and the members. The enemy had instinctively recognized Horst Wessel’s dangerousness and left no stone unturned to eliminate him.

How bitterly he must have suffered from the subsequent quarrels, how it must have hurt him, the great idealist, that members of his own ranks rose up against him and began to undermine his achievements, which he had built up with so much love and relentless labor.

He could truly have lived a quiet life. The whole world lay open to him. His mother wanted him to go on a vacation to visit his two uncles living in South America after he had passed his final exams. Horst decided against it. The bond that had wrapped itself around him and his comrades was now too tight to let him go.

He was offered the post of Oberführer in Mecklenburg, but he declined it. The struggle for Berlin, for the red East Berlin: that was his mission.

His captivating songs, which are now sung everywhere by the awakened nation, came into being. How his big eyes gleamed when he was able to present his comrades with a new song. When he sang the song “Die Fahne Hoch” for the first time at the storm evening meeting,6 probably none of his comrades-in-arms believed that he had helped create a song which today has become the liberation song of millions of Germans. The song “Die Fahne Hoch” bears witness to Horst Wessel’s genuine spirit, and it speaks of courage, pride, resistance, faith, and hope. An awakened Germany sings the song with joy and pain; it resounds equally passionately in city and country.

The song has long since become immortal. Future generations will be reminded of the time of Germany’s greatest shame, against which one of the most glorious freedom movements ran. But above all, it will recall the great blood-sacrifices that a flourishing, idealistic youth made for their fatherland.

Who in Germany today does not know the “Horst Wessel Song”? Even in the “Hohe Haus,” the Reichstag, this glorious song resounded when a hundred and seven National Socialists left the room in February of 1931 to protest against the repressive policies of the Brüning government. No meeting, no rally, no gathering of National Socialists ends before the “Horst Wessel Song” has been sung.

How proud Horst Wessel was at that time when he could announce that the song had already been requested by so and so many SA formations from all over the Reich. Even at that time we saw that the song was triumphantly spreading through Germany at lightning speed. It was as though everyone had been awaiting this song. Many a time Horst sat down at the piano at the storm evening meetings and performed a new song he had written for his comrades. Storm 5 always provided new songs, which were then carried on by the others. The evening meetings always began with a song and also ended that way. Horst always gave his storm new songs.

He brought the “Wiener Jungarbeiterlied” to Berlin, where it quickly became popular.7

The storm evening meeting was a moment of joy, when all the new thoughts and plans he had accumulated over the course of a week were shared with his comrades. Here he was in a circle of people who understood and admired him, here he came out of his shell and always made an effort to give it his all.

How jubilant everyone was when Horst announced one day that we were going to buy a shawm band. We were still a little in disbelief, but very quickly we owned one.

Despite his great masculine maturity, he had a heart like a child. He was attached to his mother and siblings with the deepest love.

But as harmonious as Wessel’s family life was, National Socialism exerted too much power. The quiet tranquility and harmony were soon destroyed. The duty to serve their fatherland tore the Wessel sons away from their mother. First National Socialism took Horst Wessel, but soon his mother also had to give her second son Werner.

Their mother once said in a conversation, “I had my sons completely under control; just one wink of the eye was enough, but National Socialism was stronger than I was.”

Werner Wessel was serving in Storm 1 at the time when Horst was expanding his storm. The two brothers went on marches together in the same unit. Even though Werner Wessel did not have the energy and leadership talent of his brother, he soon became indispensable to his storm. He also gave his storm a number of very beautiful songs, which soon became common property throughout the Berlin SA.

On December 23rd, 1929, Werner Wessel had an accident while out snowshoeing. The snowshoeing group of the Berlin National Socialists was on a trip to the Giant Mountains. They got caught in a terrible snowstorm that drove off several people from the group, including Werner Wessel. They tried in vain to make their way to the rescue hut, but the blizzard prevented all vision. Werner Wessel and the other comrades, already completely exhausted, sat down to rest. That was their downfall, for sleep overtook them and the white death claimed four blooming lives as its victims. The rescue teams set out too late; they could only recover the bodies.

On the same day, Horst Wessel paid his last respects to the murdered National Socialist Fischer with his storm. Who knew that such a terrible thing had happened at the same time? The next day, the newspapers carried the news throughout the entire Reich. The bodies of the victims were laid out in the Wang church. Werner Wessel’s mother wanted her son to be buried next to her husband’s final resting place in the Nikolai cemetery.

The transport of the deceased by rail was delayed because of the holidays. So Horst decided to take his brother to Berlin by truck. He got behind the wheel himself and drove off with a companion.

It was a sad journey through the Silesian districts. He was on the road day and night. Overtired, he set off on the journey homeward, the coffin with the body of his brother and the two other victims from Berlin behind him in the covered carriage. Exhausted, he fell asleep on the road in the middle of the night and did not wake up until late in the morning.

Werner was laid out in his parents’ home. On December 28th, he was laid to rest and thousands of National Socialists paid their last respects to the young deceased. They had carried him to the grave like a prince. When the coffin, covered with the swastika flag, was lowered into the grave, the song of the “Gute Kamerad” rang out.

Torches were flickering back and forth, and it was late in the evening when the last comrades took leave of Werner Wessel’s remains.

When Storm 5 marched through the Jüdenstraße after the funeral and passed by Wessel’s house, Horst stood at the window and silently saluted his beloved storm with his arm raised. Here was shown the symbol of a community in hardship and death.

After a long time, Horst took part in the storm evening meetings again, but it was apparent immediately that he made a crestfallen, almost broken-down impression. The usual sparkle in his eyes had disappeared, no more jokes came from his lips, and a deep sadness lurked in his being. It seemed as if he had suddenly alienated himself from his people. The death of his brother had been a heavy blow to his heart, and melancholy seemed to rule over him completely. I had never seen Horst quite happy since then; he had suddenly become another person.

All this hardship had put him on the sickbed. Spies and traitors believed that their hour had come. The storm evening meetings no longer presented the usual picture; a cold, sober tone set in. The subordinate leaders who now stepped in were at first unable to cope with the situation. Dark forces began to undermine the leader, and when they started to move against him in secret, they failed because of the cohesion of the storm.

Now Horst Wessel’s indispensability became apparent. He was the sole master of this great storm; without him the storm was a ship without a captain.

The storm evening meetings lost their charm, everyone hoped that Horst would soon reappear, and then that Storm 5 would once again become what it had been for so long: the much-feared elite storm of the Berlin SA.