6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

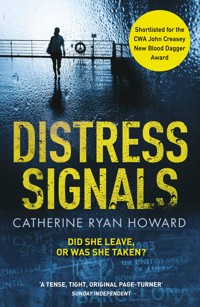

AN IRISH TIMES AND USA TODAY BESTSELLER ONE OF AMAZON UK'S 'RISING STAR' BEST DEBUTS OF 2016 WINNER: BEST MYSTERY, INDEPENDENT PRESS AWARDS 2017 USA SHORTLISTED FOR BOOKS ARE MY BAG IBA CRIME NOVEL OF THE YEAR 2016 SHORTLISTED FOR THE CWA JOHN CREASEY NEW BLOOD DAGGER 2017 SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2016 BORD GAIS ENERGY IRISH BOOK AWARDS (CRIME) Did she leave, or was she taken? The day Adam Dunne's girlfriend, Sarah, fails to return from a Barcelona business trip, his perfect life begins to fall apart. Days later, the arrival of her passport and a note that reads 'I'm sorry - S' sets off real alarm bells. He vows to do whatever it takes to find her. Adam is puzzled when he connects Sarah to a cruise ship called the Celebrate - and to a woman, Estelle, who disappeared from the same ship in eerily similar circumstances almost exactly a year before. To get the answers, Adam must confront some difficult truths about his relationship with Sarah. He must do things of which he never thought himself capable. And he must try to outwit a predator who seems to have found the perfect hunting ground... Distress Signals is a highly confident and accomplished debut novel, impeccably sustained, with not a false note. The exploration of the often murky backstage workings of the luxury liner world is fascinating, and there is a psychologically acute portrait of a killer that is genuinely moving. We will hear a great deal more of this author. - Irish Times

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

DISTRESS SIGNALS

Catherine Ryan Howard

This one’s for you.

Adam

I jump before I decide that I’m going to.

Air whistles past my ears as I plummet towards the sea, dark but for the panes of moonlight breaking into shards on its surface. At first I’m moving in slow-motion and the surface seems miles away. Then it’s rushing up to meet me faster than my mind can follow.

A blurry memory elbows its way to the forefront of my thoughts. Something about how hitting a body of water from this height is just like hitting concrete. I try to straighten my legs and grip the back of my thighs, but it’s a moment too late. I hit the water at an angle and every nerve ending on the left side of my body is suddenly ablaze with white-hot pain.

I close my eyes.

When I open them again, I’m underwater.

It’s nowhere near as dark as I expected it to be. Beyond my feet, yes, there is a blackness down deep, but here, just beneath the surface, it’s brighter than it was above.

It’s clear too. I can see no dirt or fish. I twist and turn, but I can see no one else either.

As I look up through the water, the hull of the Celebrate looms to my right, the lights of its open decks twinkling. I have a vague idea where in the rows of identical balconies my cabin is, and I wonder if it’s possible for two people to leave the same spot on such an enormous ship, fall eight storeys and land in completely different places.

It must be because I seem to be alone.

I drift down, towards the darkness. Pressure builds in my chest.

I need to get to the surface so I can take a breath. So I can call out and listen for the sounds of legs and arms splashing, or for someone else calling out to me.

I move to stretch both arms out—

A hot poker burns deep inside my shoulder. The pain makes me gasp, pulling water into my throat.

Now all I want to do is to take a breath. I must take one. I can’t wait any longer.

But the surface is at least ten or twelve feet above me, I think.

I start to kick furiously. My lungs scream.

I’m not a strong swimmer; I go nowhere fast. My efforts just keep me at this depth, neither sinking nor ascending.

The surface gets no closer.

The urge to open my mouth and breathe in is only a flicker away from overwhelming. I start to panic, flailing my left arm and legs.

I lift my face to the light as if oxygen can reach me through the water the same way the moon’s rays can, and that’s when I see a shadow on the surface.

A familiar shape: a lifebuoy.

Someone must have thrown it in.

I wonder what that someone saw.

The edges of my vision are growing dark. Everything is cold except for the spot where my right arm meets my torso; a fire burns in there. The pressure in my chest is pushing my lungs to rupture and burst.

I tell myself I can do this.

All I need to do is get to the lifebuoy.

I kick, harder and stronger and quicker now, somehow. Soon the Celebrate starts to grow bigger. I keep kicking. Then the moon gets bigger too, the water around me brighter still. I keep kicking. And just before I am sure that my lungs will burst, when they are already straining and ripping and preparing to explode—

I break the surface, gasping, sucking down air while my body tries to expel it, coughing and choking and retching and spluttering.

I can breathe.

I’m close enough to the lifebuoy to reach out and touch it. I grip it with my right arm and throw my left – hanging limp, the elbow at a disconcerting angle – over, but now all my weight is on one side of the buoy and it starts to flip.

I realise it’s only assistance, not rescue, and that even though I’m utterly exhausted I’ll have to keep my legs moving just to keep my head above water.

I’m not sure how long I can do this for.

One thing at a time. Don’t panic. One thing at a time.

I’m panting, hyperventilating, so my first task is to slow my breathing down. Breathe in. The right side of my face is stinging. Breathe out. My teeth are chattering. Breathe in.

I can’t see anyone else in the water.

In the distance off to my left are the lights of Nice, emerging from behind the Celebrate’s bow, the amber streetlights following the curve of the promenade first and then, crowded into every available space beyond, hotels and office buildings and apartment blocks. Behind me I know there is nothing but sea for hundreds of miles.

The Celebrate is towering over me, a gargantuan monster jutting out of the water and rising to two hundred feet above my head. I think perhaps I can hear tinkling music drifting down from her decks. The only other sounds are my breaths and the splashes I make in the water.

I try to be quiet, to be still, and listen for someone else making the same noises, or someone calling out—

I hear it then, faint and in the distance.

Whump. Whump. Whump.

I know the sound but I can’t remember what makes it. I’m trying to when I see something maybe fifteen or twenty feet beyond my left arm: a dark shape bobbing on the surface.

Whump, whump, whump.

The noise is getting louder.

As I stare at the shape, the gentle rippling of the water and the moon conspire to throw a spotlight on it, just for a second, and I catch a glimpse of short brown hair.

Hair I know looks a lighter colour when it isn’t soaking wet.

The body it belongs to is facedown in the water and, as far as I can tell, moving only because of the gentle waves beneath it.

Whump-whump-whump-whump-whump—

There’s a blinding glare as a helicopter bursts into the sky above the Celebrate, the noise of its motor so loud now that I can feel the sound thundering through my chest.

Its search beam begins sweeping back and forth across the water.

They’ve come for me.

My time’s almost up. I wonder how they could’ve possibly got here so fast. Didn’t I just hit the water a minute or two ago? Have I been here for longer than I think? Or have they come for someone else?

Whump-whump-whump-whump-whump.

Above me now, the helicopter dips to hover close to the surface, kicking up waves that push me off course and splash cold, salty water in my face. I kick harder. The body disappears from view and undulating waves take its place. I blink away a splash. The body reappears. A wave crashes over me. When I open my eyes a second time, the body is gone again.

Whump-whump-whump-whump-whump.

The sound is tunnelling a hole in my brain. It’s not above me any more but in me. I feel like it’s coming from inside my head.

Then, the grip of a hand on my arm.

Everything is bright with white light now. Am I hallucinating? Is that what happens when you go into the water from several storeys up, possibly dislocate your shoulder, nearly drown and then exhaust yourself trying to stay afloat in open sea?

But no, there really is someone by my side, a man in a wetsuit with an oxygen tank on his back. All I can see of his face are his eyes through the foggy plastic of his mask. He lifts it up over his nose and says something to me, but the words are lost in the helicopter’s deafening roar.

I turn away from him and try to find the body again. I scan the surface but I can’t see it now.

A bright-red basket is dropping on a rope. The wetsuit man grips me under the arms and pulls me towards it.

He speaks again, this time shouting right into my ear from directly behind me.

This time, I hear him.

‘Is there anybody else in the water? Did you see anybody else in the water?’

I say nothing.

I focus on the belly of the helicopter. It’s navy blue and glossy. I think I see a small French flag painted on the underside of its tail.

‘Was it just you?’ he shouts. ‘Did you go in alone?’

We reach the basket and another wetsuit man. Together they lift me into it.

I am now looking up at the night sky. It seems filled with stars.

The man’s face appears above mine, blocking my view of them.

‘Can you hear me?’ he asks. ‘Can you hear me?’

I nod.

‘Were you alone in the water? Did you see anyone else?’

Above me the helicopter’s blades spin. Whump-whump-whump-whump-whump. Out of the water, the pain in my shoulder is sharper. I start to shake.

All I wanted was to find Sarah.

How has it come to this?

‘No,’ I say finally. ‘It was only me in the water. There is no one else.’

Part One

LOVE IS BLINDNESS

Corinne

Even at 5:45 a.m. the Celebrate’s crew deck wasn’t empty.

Something fleshy and pink and snoring was splayed on an inflatable chair bobbing at one end of the swimming pool. A young stewardess reclined on a sun-lounger, smoking, her red and yellow uniform revealing that she worked the breakfast buffet and either slept in her clothes or stored them in a ball on the floor of her crew cabin. Huddled around one of the plastic tables, three security guards argued in English about a soccer match and some goal that should never have been allowed.

Shifts ran constantly and around the clock; the midnight buffet clear-up finishing only minutes before the breakfast prep had to start. It was always someone’s spare moment before work or smoke break or post-shift crash. With the crew quarters impossibly cramped, below the water line and always smelling faintly of seawater and sewage (and, sometimes, not so faintly), everyone dashed outside to the crew deck whenever they could.

Blinking in the sunshine, Corinne stepped out onto it now and paused for a moment while her eyes adjusted to the light. There was an unoccupied table and chairs on the portside. Careful not to spill either of the two coffees she was carrying, she headed for it.

As she passed the table of security guards, Corinne felt the gaze of one of them crawling up her cabin attendant’s uniform to her face. The flash of him she’d caught with her peripheral vision left a vague impression of youth, broad shoulders and closely cut blond hair. The man’s eyes, she felt sure, stayed on her all the way to the table and lingered after she sat down.

She didn’t entertain for a second the notion that this attention was down to admiration or attraction. He was at least three decades her junior and Corinne’s face wore many more years than she’d lived. On top of that her hair was grey, her body weak and painfully thin. That left mild interest (What is a woman of her age doing working on a cruise ship?), which was fine, but also suspicion (What is she really doing here?) and recognition (Don’t I know her from somewhere?), which were not.

The table was unsteady on its legs and Corinne had to lean her elbows on it to keep it from rocking. It was also missing its parasol and one off-white plastic leg was pockmarked with cigarette burns – ‘crew grade’, in company-speak. Everything the crew had was second-hand, from the flat, stained pillows on their bunks to the chipped crockery in their mess, all of it already used and abused by paying passengers until Blue Wave deemed it no longer good enough for them.

Corinne sipped her coffee until she felt the guard’s attention fade and a quick glance confirmed his focus was back on the football debate. Then she checked her watch. She had about five minutes before Lydia arrived, tired and wired after her overnight shift.

Lydia was her cabin-mate and, over the past week – the first for both of them aboard the Celebrate – they had fallen into a pleasant routine. They met for coffee on the crew deck just after Lydia finished her shift and before Corinne started hers, and again in the mess just as Corinne was ending her work day and Lydia was gearing up for another one. Lydia was very young – only twenty-one – and had never been away from her home in the north of England before. Corinne suspected the girl found comfort in the company of a woman her mother’s age. Not that Corinne minded in the least. Lydia was a warm, cheerful girl, and it was nice to have someone to talk to about normal, everyday things. The world outside the shadow.

There was just enough time. Corinne pulled a small notebook from a pocket in her uniform skirt and laid it on the table beside her coffee cup, angling her body so that nobody else would be able to read what was on its pages.

The bridge towered into the sky behind her. All the crew’s outdoor space was sunk into the bow, another cabin attendant had told her, because there was nothing else a cruise ship could do with the open deck immediately below the bridge. You couldn’t put bright lights there for safety reasons, and paying passengers needed bright lights. So with the curved white walls of the bow rising up around them, the crew had the only swimming pool on board that didn’t offer a view of the sea.

For all Corinne knew, he could be one of the officers at the Celebrate’s helm right now, boring holes into her back. From what she’d seen on TV and in movies, officers on the bridge had access to binoculars. She couldn’t take any chances.

The sea breeze blew the notebook open, flipping a few pages with rapid-fire speed. Corinne pressed a hand to it to stop it from blowing away. It was a small diary, the week-to-a-view kind, with her own small, neat handwriting filling the spaces for the last four days with short notations.

Cabine 1002: lit parfait?

Rien.

Cabine 1017: Valises, mais pas des passagers . . .

Cabine 1021: Ne peut pas entrer – le mari dit la femme est malade.

Sunday: the bed in 1002 hadn’t been slept in. She’d found nothing out of the ordinary on Monday. Tuesday: belongings in 1017, but no passengers for them to belong to. Then on Wednesday, a request through the door of 1021 that she not disturb them, from a male passenger who said his silent wife was sick in bed.

All these incidents; they’d all come to nothing.

She’d keep looking.

In the little pocket at the back of the notebook, there was a single sheet of folded paper. Corinne retrieved it now. She glanced over her shoulder. No sign of Lydia yet. No one else on deck appeared to be paying any attention to her. She unfolded the page. Laid it flat on the table in front of her, smoothed out the creases with the palm of her hand.

Then, as she did every morning, she looked at the black and white photograph printed on the lower half of it, studying the man’s features. She closed her eyes, recalled the face from memory. Repeated this a few times until she could remember every last detail.

Looked at him and said, silently, I will find you.

Maybe today will be the day.

Then she carefully refolded the page and placed it back in the notebook, and put the notebook back in the pocket of her uniform.

Lydia would arrive any second.

Corinne couldn’t afford to get caught.

Adam

The night before Sarah left was only unusual in that we didn’t spend it at home.

We nearly always stayed in on a Saturday, taking up our established positions on the couch for a relaxed evening of pizza, bad-singing-competition-TV and good subtitled Scandinavian dramas.

I didn’t much like Going Out Out, as the kids called it, the kids being what I called everyone under twenty-five since I’d turned thirty six months ago.

Officially my stance was that Ireland’s binge-drinking culture should not be a cultural claim to fame we were proud to promote, but an embarrassing problem we were desperate to solve. Our newly graduated youth, blinking in the harsh light of the real world, were faced with just two options: join the queue for the dole or join the queue for Canadian work visas. It would drive anyone to drink.

That had to be why they did it, right? To numb their pain? Because it couldn’t be for fun, could it? A typical Saturday night’s going out out, as far as I could tell, started with you being sad you were sober, ended with you wishing you weren’t so drunk and, in between, all you did was queue for things: for service at the bar, to get into the club, to use the toilets, for a box of greasy fried chicken, for a taxi home.

That’s what I said, anyway.

The real reason I didn’t like it was because Cork felt like an ever-shrinking city where a run-in with an old school-friend or former college classmate was never more than a corner away. There was a limit on how many ‘What are you up to these days?’ a guy could take when he wasn’t up to very much.

‘I’m writing,’ I would say. ‘I’m a writer.’

Me: hating myself for how sheepishly I said it.

Them: confused frown.

‘Screenplays,’ I’d add. ‘Movies?’

‘Oh, right.’ The enquirer would nod. ‘Nice. But I meant, like, for work. What do you do?’

Sometimes I skipped the writing thing altogether and confessed immediately to whatever temp job I’d taken that week, stapling things together in some generic office or answering phones in a call centre. The spotty teens I’d left behind me when I’d dropped out of university were now young professionals collecting good salaries from investment banks, legal firms and software giants. They’d graduated during the Boom and avoided the landmines of the Bust, mostly. Their news was about promotions and bonuses and company cars, while I was still excited about the fact that scrawled across the top of my latest rejection letter had been my name. My name! Personalisation: progress, at last.

But it proved difficult to explain the concept of failing upwards to a casual acquaintance who really only wanted to know whether or not you’d gone back on the dole.

‘God, so bloody what?’ Sarah used to say in the cab on the way home, ducking underneath my arm so she could lean her head against my chest, the degree of her exasperation in direct proportion to how many drinks she’d had. ‘I don’t know why you let them get to you. You still have your dreams.’

‘Ah, yes,’ I’d say. ‘My dreams. What’s the current exchange rate on those, do you think? My phone bill is due.’

‘Well, you also have a gorgeous girlfriend. Who believes in you. Who knows you’re going to make this happen. Who has no doubt.’

‘None at all?’

‘None whatsoever. Can we get take-away? I’m starving.’

‘But you’ve no evidence. And I think the take-away is closed.’

‘That’s what belief means, Ad. I mean, really.’ A poke in the ribs. ‘Aren’t you supposed to be a writer or something?’

I joked about it, yes, but the truth was it got to me. I’d been trying to make this writing thing happen for years. Fantastical dreams were fine in your twenties, but I was thirty now. When even I had started to wonder if I should let my fanciful notions go, talking about them with people who had already moved to the Real World made it harder to convince myself that, no, I shouldn’t. Not yet.

I started making excuses, coming up with reasons to stay in on Saturday nights. I was tired. I was broke. We were broke because of me. Whatever my story, Sarah would nod, understanding, and our conversation would move on to deciding between a box-set re-watch or tackling our Netflix queue. Sometimes she went out with the girls and I was glad she did, because I wanted her to do what she wanted and those nights typically won me a few weeks’ reprieve. We still went out together every now and then, but eventually our go-to pub had a new name and our go-to club had closed down. I no longer recognised the songs that won especially loud cheers from the crowd when the DJ played them, and had no clue as to why we were all suddenly drinking out of jam jars with handles on.

But that was before. Now, things were changing.

Finally.

‘I bet it’s like turning eighteen,’ Sarah said as we manoeuvred around each other in the bathroom, getting ready. I was already dressed; she was wrapped in a bath towel. ‘From the moment you can produce ID, nobody bothers to ask for it.’

‘So tonight no one’s going to go, “But what do you actually do?” because for once I actually want them to?’

Oh, me? I’m a writer. Screenplays. Yeah, not doing too bad, actually. Just made a sale. Major Hollywood studio, six figures. For a script I wrote in a month.

‘Exactly.’ Sarah was putting on an earring, fiddling with the back of it. ‘They all know already anyway. You were on the cover of the Examiner, remember?’

I moved behind her, met her eyes in the mirror over the sink.

‘And,’ I said, ‘the back page of the Douglas Community Fortnightly.’

‘And that advertiser thing you get free in shopping centres.’

‘That was the one with the very good picture.’

‘That wasn’t of you.’

‘It was still a very good picture.’

Sarah laughed.

‘So who’ll be at this thing?’ I asked. ‘Anyone I know?’

We were going to a going-away party. If the pubs and clubs of Ireland had worried that austerity would damage their trade they needn’t have; there were enough pre-emigration shindigs these days to keep the industry afloat all by themselves. That night it was the turn of Sarah’s colleague, Mike, who was heading to New Zealand for a year.

‘Susan will be there. James – you met him before, didn’t you? And Caroline. She’s the girl we ran into the night of Rose’s birthday. You know Mike, right? Don’t think you’ve met the rest of them . . .’

While Sarah was saying this, I wrapped my arms around her waist and rested my chin on her shoulder, savouring the fruity smell of some lotion or potion as I did.

There was no long fall of blonde hair to move out of the way. Just that afternoon Sarah had walked into a hairdresser’s and asked for it all to be chopped off. That morning, the ends of it had been tickling the small of her back. Now it was clear off her neck. The cut had exposed more of her natural warm-brown colour, and I think it was this that made her eyes appear bigger and bluer than they had before. She also seemed more grown-up to me, somehow, and there was something incredibly distracting about all that exposed skin . . .

I pressed my lips against the spot where her neck met her left shoulder.

Sarah said she’d decided to get the haircut on a whim, that she’d just decided to do it after seeing a picture in the salon’s window as she walked by. But a week from now, I’d learn that she’d made an appointment with the salon a week earlier.

‘Just don’t abandon me, okay?’ I murmured.

I was expecting one of Sarah’s trademark eye-rolls and a sarcastic remark. Maybe a reminder that I was now, technically speaking, a big-shot Hollywood screenwriter and could surely hold my own in conversations about Things Adults Do instead of standing on the periphery, smiling at the right moments but otherwise only moving the ice-cubes in my drink around with a straw. Or perhaps Sarah would point out that I didn’t need to go to this thing, that it was a work night out, that she’d been going by herself until I’d moaned about spending the night before she left for nearly a week home alone, prompting her to – eventually – say, fine, tag along.

But instead she turned to face me, wrapped her arms around my neck and said: ‘I would never abandon you.’

‘Well, good. Oscar night will be stressful enough without having to find a date for it.’

I kissed her, expecting to feel her lips stretched into a smile against mine. They weren’t. I moved my mouth to her jawline, down her neck. There was a faint taste of something powdery, some make-up thing she must have just dusted on her skin. I brought my hands to her waist and went to un-tuck the towel.

‘Ad,’ Sarah said, wriggling out of my arms. ‘I booked a cab for eight. We don’t have time.’

I looked at my watch. ‘I suppose I should take it as a compliment that you think that.’

‘Funny.’ An eye-roll. (There it was.) ‘Can you grab Mike’s card? I think I left it on the coffee table. I’m nearly done here. I just have to get dressed.’

I turned to leave.

‘Oh, Ad?’

I stopped in the doorway.

Sarah was in front of the mirror, twisting to check her hair. Without looking at me, she said, ‘I meant to tell you: the others aren’t exactly delighted about me being the one to get to go to Barcelona. They’ve all been milking it with their honeymoons and their maternity leave but God forbid I get to have a week out of the office. I mean, it’s not like I’m off. I’m there to work. Anyway, I’ve been trying not to go on about it, so . . .’

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘I won’t bring it up.’

I smiled to myself as I crossed the hall into the living room. Honeymoons and maternity leave. Now that I’d sold the script, we could finally start making our own plans instead of being forced to watch as the realisation of everyone else’s clogged up our Facebook feeds.

But first . . .

I collected Mike’s card from the coffee table, then dropped into my preferred spot on the couch. It offered a clear line of sight to my desk, which was tucked into the far corner of the living room and so, crucially, was only a few feet from the kitchen and thus the coffee-maker.

A stack of well-thumbed A4 pages were piled on it, curled sticky notes giving it a neon-coloured fringe down its right side. I got a dull ache in the pit of my stomach just looking at it.

The rewrite. I had to start it tomorrow. And I would. I’d drive straight home after dropping Sarah at the airport and get stuck in, make the most of the few days and nights that I’d have the apartment to myself.

Sarah emerged from our bedroom, wearing a dress I hadn’t seen before.

The money from the script deal hadn’t arrived yet but, since I’d learned it was on its way, I’d been melting my credit card. Sarah had supported me for long enough, paying utility bills and covering my rent shortfalls with money she could’ve been – should’ve been – spending on herself. That morning I’d sent her into town with a gift-card for a high-end department store, the kind that comes wrapped in delicate tissue and in a smooth, matt-finish gift bag.

‘This is just a token,’ I’d said. ‘Just a little something for now, for tonight. You know when the money comes through . . .’

‘Ad, what are you doing? You don’t know how long that money is going to take to arrive. You should be hanging onto what you’ve got.’

‘I put it on the credit card.’

‘But you might need that credit yet. I really wish you’d think before you spend.’

‘Look, it’s fine. We’ll be fine. I just wanted to . . .’ Sarah’s mouth was set tight in disapproval. ‘Okay, I’m sorry. I am. It’s just that I don’t want to wait to start paying you back for . . . For everything.’

She’d seemed annoyed. Disappointed too, which was worse. But then, later, she’d come home with a larger version of the same bag, and now she was twirling around to show me the dress that had been inside it: red and crossed in the front, the skirt part long and flowing out from her hips.

‘Well?’ she asked me. ‘What do you think?’

She looked beautiful in it. More beautiful than usual. But with the new hair, not quite the Sarah I was used to.

‘Nice,’ I said. I pointed to my jeans and my dark, plain T-shirt. ‘But now I feel underdressed.’

‘Change, if you want to.’

Our buzzer went. The cab was here.

‘No, it’s fine,’ I said. ‘Let’s just go.’

Aside from the clothes Sarah was wearing when I drove her to the airport the next morning, that red dress was the only item I could tell the Gardaí was missing for sure.

Cork International Airport, all eight gates of it, is perched on a hill to the southwest of the city. Each year it reportedly begins nearly one out of every three days shrouded in thick, dense fog, the kind that delays take-offs and hinders landings and which once, a few years ago, contributed to a fatal crash-landing on the runway. In other words, it was a terrible place to build an airport. Ask any Corkonian about this and they’ll mutter something about how the airport’s planning application must have come clipped to a bulging brown envelope stuffed with cash.

On that Sunday morning the skies were clear but dark clouds waited on the horizon, threatening showers later in the day. Typical August weather for Ireland: warm enough to be muggy, with the ever-present threat of torrential rain.

It was a ten-minute drive from our apartment to the terminal’s doors. Sarah was at the wheel.

‘I could be coming with you,’ I said to her as the car passed through the airport’s main gates. ‘I could put the flight on the credit card, stay in your room.’

‘It’s only supposed to be me in there.’

‘Who’d know?’

‘The hotel, and so would work once they received the bill. In Spain each guest has to hand over their passport so the front desk can make a copy. Every guest’s name has to go on the register.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘I think Susan told me.’

‘We could sneak me in.’

‘You need to work.’

‘I could work while you do.’

‘Adam,’ Sarah groaned. She looked over at me to see if I was being serious.

‘Relax.’ I held up my hands. ‘I’m just joking.’

We’d already talked about me going to Barcelona, back when Sarah had first found out that she had to go. But the only way to not get her into any trouble would’ve been to book another hotel room just for me, and there was no way we could afford to do that. A week later, I sold the script. But selling it meant I had to rewrite it, and the rewrite was due just after the Barcelona trip. So now I didn’t have the time to go.

‘Sorry,’ Sarah said. ‘It’s just . . . Well, you know. The flight.’

She didn’t like flying and knew what rain clouds over the airport meant: a bumpy take-off. I’d been purposefully avoiding the subject.

‘How long is it?’ I asked.

‘Couple of hours.’

‘That’s not too bad. And you’re going straight to the hotel when you land?’

Sarah nodded.

‘Text me when you get there.’

‘Yeah.’ She glanced at me. ‘So what were you and Susan talking about last night?’

‘What? When?’

‘When I came back from the bar, you two looked like you were deep in conversation.’

‘She asked me for advice,’ I said. ‘Turns out she’s not just all breasts and hair. She wants to be a writer. Who knew?’

‘Not me,’ Sarah said. The car pulled to the right, getting in lane for Departures. ‘In all the years I’ve worked for her, I’ve never heard her so much as mention such a thing. I don’t think I’ve ever even heard her mention books. Then, what do you know, my boyfriend makes a script sale and suddenly she’s all over him like a rash, asking for advice.’ A pause. ‘So that was it?’

‘What?’

‘All you and Susan talked about.’

‘Yeah, pretty much. Why?’

‘Just wondering.’

‘You aren’t . . .’ I raised my eyebrows and waited for Sarah to look over and see.

‘What?’

‘I mean, I know I’m quite the catch now that I can make a living in my underwear and everything, but you don’t need to worry.’

Sarah parked the car in the Taxis Only lane outside the terminal building, killed the engine and turned towards me.

‘Ad, what are you on about?’

‘I’m just saying. Jealousy is a terrible thing.’

‘What the—’ Sarah stopped, getting it. ‘Yeah. You and Susan Robinson. Right.’ She rolled her eyes. ‘Although I suppose women will be all over you now that you’re rich and famous.’

‘I think you mean anonymous and poor.’

‘You won’t be poor soon.’

‘We won’t be. Anyway, this is me we’re talking about. If by any chance any girls make the mistake of being all over me, as soon as I open my mouth they’ll be on their way again. Remember when we first met? What did I start talking about immediately?’

A hint of a smile tugging at her lips. ‘Star Wars?’

I glared at her. ‘Star Trek.’

‘Is that different?’

‘I’m not going to react to that because I know you know that it is.’

‘That’s my point. Girls love that crap now. Geeks are in.’

‘I think you have to have a beard for that though.’

‘Don’t all writers have beards? You could grow one.’

‘I know I could, but you’re thinking of novelists,’ I said. ‘And poets. Poets have the best beards. Screenwriters do it clean-shaven. We like baseball caps and the combination of beard and baseball cap is just too much. But maybe I could start to wear glasses or—’

A horn blew somewhere behind us.

‘Shit,’ Sarah said, twisting in her seat to look behind her. ‘Am I parked in the wrong place? I am. Shit.’ She reached into the back seat for her handbag. ‘What time is your talk tomorrow?’

‘The one you’re missing? Twelve.’

It had been a last-minute thing, a request from my university to talk to some of their Film Studies students.

The university I’d dropped out of, mind you. Apparently all was forgiven.

‘You wouldn’t have let me come anyway,’ Sarah said.

‘You’d make me nervous. I can only talk in front of strangers.’

‘Didn’t you say Moorsey was going?’

‘He’s not sure if he can get off work yet.’

‘So you can talk in front of him but not me?’

I shrugged my shoulders as if to say I don’t make the rules. I didn’t want to get into my real motivation for inviting Moorsey. It was a test.

‘Then you’re just going to write?’

‘As much as I can.’

‘I’ll try not to disturb you.’

‘Don’t,’ I said, reaching to take Sarah’s hand. ‘I want to hear from you. I’ll miss you.’

‘I mightn’t have time to. They’ve got me booked into I don’t know how many sessions at this conference—’

A cacophony of angry horn-blowing began behind us.

‘Come on,’ Sarah said, letting go of my hand and pushing open the driver’s door. ‘Before there’s a riot.’

We both got out of the car and met at the boot. I pulled Sarah’s case out for her and set it on the ground.

‘What time are you in Thursday?’ I asked.

‘One-ish, I think.’

‘I’ll be here.’

I held her as we kissed quickly, lightly. Behind us, the horn-blowing grew more enthusiastic.

Sarah pulled away first. She grabbed the handle of her case and turned towards the terminal.

‘Have fun,’ I said.

Over her shoulder: ‘It’s work!’

I called after her: ‘Yeah, but it’s work in Barcelona!’

I got back into the car and readjusted the rear-view mirror until it filled with the angry face of a taxi driver and his extended middle finger. I waved apologetically at him and pulled off.

Sarah was just a few steps from the terminal doors when I did.

That morning she was wearing dark-blue jeans, a white T-shirt with navy horizontal stripes and a pair of those cheap, flat shoes women seem to love that must give podiatrists nightmares. She was also wearing a scarf, navy with white butterflies on it, not because it was cold but because she felt cold, what with her newly uncovered neck. A beige trench-coat hung from the crook of her arm. There was a small leather bag slung over one shoulder and she was pulling a cabin-approved, bright-purple trolley case along the ground behind her.

She’d packed light, she said. It was only going to be four days.

That afternoon, at 4:18 p.m. Irish time, she sent me a text message assuring me that she’d landed safely and had made her way to the hotel. She’d collected a schedule of the conference and it was going to be an even busier and more demanding affair than she’d been expecting. I wasn’t to worry if she didn’t manage to call or text much, she said. I was just to get writing and stay writing. She’d see me on Thursday.

The last line of her text message read:

I won’t even get to see Barcelona! :-(

If I’ve learned anything these past couple of weeks, it’s this: the most effective lies are the ones that are almost the truth.

Moorsey didn’t come to the talk.

I spoke for about an hour to a class of a hundred or so Film Studies students who’d packed into a lecture theatre in the basement of the Boole Library. Row after row of eager faces, Apple products and slogan T-shirts. En masse, they looked like they could eat me alive.

I smiled nervously at the wall at the back of the room while some professor or other introduced me. I’d never done anything like it before, but as soon as I started talking and realised that I was, in their eyes, the only one with the information they needed, I started to relax. Individually they may have phrased their questions in slightly different ways, but essentially they all wanted to know the same thing: how had I come up with an idea for a screenplay and written it down and secured an agent and made a sale, and done it all from my little desk in Cork?

‘The short answer,’ I’d quipped, ‘is one decade and the Internet.’

That got a good laugh. I made a mental note of it. I’d definitely trot that gem out again.

Afterwards, a man who said he was the course convener – whatever that meant – asked if I’d be interested in coming back for a practical screenwriting session.

‘We want to take full advantage of this,’ he said. ‘Having a Hollywood screenwriter right here in Cork!’

I fished a grubby-looking business card out of my wallet and told him to call me any time.

I made another mental note: get new business cards.

‘I dropped out of here, you know,’ I said, still riding a wave of confidence.

‘Oh?’

‘Three weeks, I lasted. One of them was Freshers’ Week.’

‘How long ago?’

‘2001.’

‘What course?’

‘English.’

The next line was supposed to be Maybe you’ll go back someday. That’s always the way this conversation went.

But this guy said, ‘Well, third-level education isn’t for everyone. You must be thrilled though. After all your hard work.’

I admitted that, yes, I was thrilled. Thrilled and a little overwhelmed. I said it was as if I’d spent my whole life insisting on the existence of an invisible friend and now, suddenly, everyone else could see him too.

The convener looked confused.

‘Well, thanks for today,’ he said, reaching out to shake my hand, ‘and best of luck with it all. We’ll be in touch.’

Mental note no. 3: retire the invisible friend analogy.

I pulled out my phone as I crossed the Quad, heading through the campus in the direction of Western Road, where I’d left the car. Drops of moisture landed on my screen as I checked for missed calls or new text messages.

There was still nothing from Sarah.

I’d sent her two messages last night and one earlier today. Why hadn’t she replied?

I thought back to what I’d sent her: inane updates about the finale of a TV show we watched and my observation that the coffee she’d brought home on Saturday from one of those giant discount German supermarkets actually didn’t taste too bad, and I tried to see them as Sarah would: evidence that I wasn’t writing. She was well aware I had a procrastination problem. Her not replying might just be her not encouraging me. And she was busy; she’d told me she would be. But had she got the messages in the first place?

I opened WhatsApp and typed a quick message to her.

...As soon as I pressed Send, a single checkmark appeared next to my message. After Sarah read it on her end, there’d be two. That way I’d know that she’d seen it, at least.

There was a text message from Moorsey, saying he couldn’t get off work but that he was having his lunch in Coffee Station if I was free to join. I checked the time: just gone one o’clock. I texted him back and said I was on my way.

Moorsey – Neil was his actual name, Neil Moore, but even his own mother called him Moorsey and he wouldn’t respond to anything but – had done everything right that I’d done wrong. I’d known him since secondary school, where he’d studied hard to get maximum points in his Leaving Cert and an award for the highest marks in Physics in the whole of Ireland. We’d both gone straight into University College Cork but he’d lasted the full four years and graduated with a first, then got some big job with the Tyndall Institute. Something to do with nanotechnology, although, typical Moorsey, he’d tell you it was mostly entering numbers on spreadsheets all day long, boring really. He’d bought a sensible house (two small bedrooms in a commuter town, price slashed because the estate was unfinished) and a sensible car (a people carrier, second hand) before I’d even managed to leave my childhood bedroom. My parents loved him, loved using him as the standard I should have aspired to. Moorsey and I joked that he was like the son they never had.

But I’d always been happy for him. He deserved it; he’d always worked hard. Moreover, he’d always listened intently while I rambled on about screenwriting books and McKee seminars and the latest batch of rejection letters that, as per Stephen King’s instructions, I was keeping impaled on a nail hammered into my bedroom wall.

Since the script sale though, something felt off between us. I wasn’t surprised he hadn’t made it to my talk, nor that my consolation prize was a limited block of time in which conversation would be hampered by the chewing of food.

I found him sitting inside the window of the cafe, a Coke and a card saying ‘23’ on the table in front of him, the card angled towards the waiting staff.

Moorsey was an Irishman straight from Central Casting: fiery-red hair, skin so pale it was bordering on translucent, a spill of freckles all over his face. Today he was wearing jeans and a T-shirt with the molecular structure of caffeine on the front of it. (Not that I’d recognise the molecular structure of anything. He’d worn it – and explained it to me – before.) Whenever I began to worry that I was still wearing the same kind of clothes I had when I’d dropped out of college, that I didn’t own the tailored blazers, inexplicably tight jeans or expensive-yet-scuffed-looking brown shoes I saw all the other men my age wearing, I thought of Moorsey and felt better.

And tried not to think about the fact that he had a PhD.

‘I ordered for you,’ he said as I sat down. ‘A club.’

‘Perfect, thanks.’

‘How did the thing go?’

‘Great,’ I said. ‘I was really nervous before it started but, actually, once it got going, I was fine. I was good. I was funny.’

Moorsey blew air out of his nose in a lazy laugh, but said nothing.

‘They wouldn’t let you out of work?’ I asked.

‘No, sorry. We have this big deadline on Friday. A project’s due.’

‘It’s fine. Don’t worry about it.’

‘Next time.’

‘Yeah.’

There was a beat of silence then, broken by the clink of ice-cubes in Moorsey’s Coke as he took a sip from it.

Another conversational dead-end.

I asked after Rose.

A few months ago, Moorsey had finally found his balls and made a move on Rose, Sarah’s best friend. We’d all known each other since college, and Sarah and I had known that Moorsey liked Rose for about that same amount of time. I thought it was great they were together.

‘Rose is fine,’ Moorsey said. ‘Actually, I have some news. We’ve, ah, moved in together.’

‘Have you? Wow.’ In all the time I’d known Moorsey, he’d never lived with anyone besides his parents and his younger brother. This was a big deal. Things must be getting serious. ‘Wow,’ I said again.

‘So you’re wowed, is what you’re saying?’

‘When did this happen?’

Moorsey shrugged, embarrassed. ‘Couple of weeks ago.’

Couple of weeks ago. That stung but I didn’t let on. Why hadn’t he told me sooner? I hadn’t seen him much since then, but we had talked. Texted. Why hadn’t he mentioned that his first-ever serious girlfriend had moved in with him?

Come to think of it, why hadn’t my girlfriend told me the news, seeing as she must have known too?

‘Moorsey,’ I said, leaning forward. ‘Have I been a total dick lately?’

‘What?’

‘Have I been a dick? About the screenplay thing?’

‘No. Not at all.’

‘You’re sure?’

‘Trust me when I say I’d let you know if you were.’

‘Okay.’

I sat back again.

‘Why do you ask? Did someone say something?’

‘No, it’s just . . .’ I shrugged. ‘I don’t know. I thought maybe you were annoyed with me.’

Moorsey snorted.

‘Jesus, Adam. You know, I think the stress of Hollywood is getting to you. It might be time to move out of LA. Get a place on the coast. Santa Monica, maybe. Then we can stalk Jennifer Lawrence together, like we’ve always dreamed.’

I laughed.

‘Okay, okay. Sorry. Maybe the stress is getting to me. They sent me notes, you know? After the sale. Honestly, there were pages and pages and pages.’ I hadn’t said this aloud to anyone yet, but now I pushed out the words that had been running around inside my head for more than a week. ‘I wonder why they bought the script at all, because it seems like they want everything in it to be different. To be honest, the thought of it . . . I’m struggling to even get started.’

My phone beeped with a text message.

‘Mum,’ I told Moorsey as I read it. ‘She’s made a batch of curry and wants to drop some of it over tonight so I don’t starve to death while Sarah’s away. Great.’

‘I love your mother’s curry.’

‘Feel free to come and collect it then. I’ve been avoiding it since she started adding peas back in ’98.’

‘You remember the year?’

‘It was a traumatic time.’

‘Why not just tell her to leave them out?’

‘She thinks they’re her signature ingredient.’

‘But I’ve seen peas in lots of—’

‘I know, I know. I don’t want to burst her bubble.’

A waitress appeared with our sandwiches. I ordered a coffee from her.

‘Where is Sarah?’ Moorsey asked. ‘Rose said something about her being away with work . . . ?’

Later, replaying this conversation in my head, I’d recall how he’d looked out the window as he’d asked me that.

‘She’s in Barcelona. At a conference.’

‘Nice. You didn’t want to go too?’

‘I couldn’t. I have the rewrite.’

‘How’s she getting on?’ Moorsey asked his sandwich.

‘Actually, I don’t really know.’

I picked up my club and started pulling out the chunky tomato pieces, eyeing my phone on the tabletop while I did. Still no new calls or text messages. By now, I hadn’t had any contact with Sarah for nearly a whole day.

When I looked up again, Moorsey was looking at me questioningly.

‘She knows I need to write,’ I said. ‘She’s trying not to disturb me.’

When my phone rang late on Tuesday morning, the sound jerked me from a deep sleep. I’d been up until four-thirty, trapped in a cycle of checking Twitter, admonishing myself for checking Twitter and then staring at my script on screen until I gave in and checked Twitter. This had gone on for hours until, finally, I’d crawled into bed, defeated.

Groggy and disorientated now, I peered at my phone’s screen. The call was from a blocked number.

I thought: Sarah.

And: it’s about time.

‘Hello?’ It came out as an incoherent croak. I coughed and tried again. ‘Hello?’

‘Adam, is that you?’

A woman’s voice. Older. It took me a moment to place it.

‘Maureen. Hi. How are you?’

I sat up, rubbed the sleep out of my eyes and wondered what Sarah’s mother could possibly be calling me for.

Sarah had only one sibling: a brother, Shane, who lived in Canada and was nine years her senior. If you listened to the conspiratorial whispers of the relatives that cornered me at O’Connell family weddings and squealed, ‘You two’ll be next!’, Shane’s arrival had been purposefully postponed and then Sarah’s had come as quite the surprise. My own parents had taken a different tack: they got married young, had (only) me nine months later and then bided their time until I turned eighteen – or twenty-two, as it turned out – when they got their lives back, duty done. As a result, our two sets of parents seemed to me to be of entirely different generations. Mine were vibrant, strong and active while Sarah’s were quiet, subdued and frail. I wanted to reel mine in sometimes while I felt like hers needed some looking after.

‘God is good,’ Maureen said. ‘Yourself?’

‘Grand, thanks.’

‘How’s the film going?’

Like all Corkonians, Maureen pronounced it fill-um. I’d taken to saying ‘movie’ instead to avoid embarrassment.

‘It’s fine,’ I said. ‘Going well.’

I’d long given up correcting her and Jack’s misperception that what I was doing was movie-making. Positive-sounding generalities were the way to go.

‘Were you doing something yesterday, did I hear?’

‘Yeah. A talk. In UCC.’

‘UCC? Really? Well, isn’t that great. Good for you, Adam.’

I smiled at this. Although I knew they liked me – they thought I was nice and kind and well brought up, Sarah said – Jack and Maureen had always frowned upon my wanting something other than a 9–5 job because, in their minds, those were the only jobs around. As far as they knew, the sole equation that worked was good Leaving Cert + college degree + straight into pensionable job, and they prayed (literally prayed – novenas, mostly) that I would realise this before the hat-shopping began. The script sale then was like a stress-test for everything they believed about how to get ahead in life, and I knew they were struggling now with how to respond to it. Maureen had just paid me a kindness.

‘Is herself awake?’ she asked.

‘Her . . . Sorry?’

‘Sarah. Is she awake? I said to myself she’s probably asleep so I called your phone instead. Are you at home?’

‘I . . . I am, but . . .’

She thinks Sarah is here?

She’d forgotten that Sarah was in Barcelona and, what, she thought she could be sleeping at home this late on a weekday morning? Maureen was famously forgetful, but still, this seemed odd. Had we graduated from looking for reading glasses that were on her head and circling Tesco’s car park twice to find the car, to forgetting that her own daughter was in another country?

‘But, Maureen,’ I said. ‘Sarah’s in Spain.’

‘What, love?’

‘Sarah’s in Barcelona,’ I said. ‘With work. There’s a conference on, Monday to Wednesday. She flew out Sunday morning and she’s back Thursday lunchtime.’ Remember? I waited for her to say that she did. When there was no sound on the line I said, ‘She didn’t tell you?’ even though I didn’t think for a second that that could be true.

Away from the receiver, Maureen said: ‘He says Sarah’s in Spain.’

A gruff male voice in the background: Jack. ‘What? But, sure, that doesn’t make any sense.’

‘Are you looking to talk to her?’ I said. ‘She has her phone.’

Maureen, back to me: ‘We’ve been calling it. We can’t get through.’

A rustling sound as the phone changed hands, then Jack’s voice loud in my ear. ‘We’ve been calling her since this time yesterday. There’s no answer.’

‘Well, I’m sure she’s just busy. There’s the conference—’

‘First it was ringing and ringing, but now it goes straight to the answering machine. Maureen sent some texts and left a message but she didn’t call us back, so we rang the office just now. The receptionist told us that Sarah’s out sick. Has been since Monday. We presumed she was at home, so we called you. Now you say she’s in Spain?’

‘She is.’ I repeated to Jack what I’d already said to Maureen: Barcelona, a conference, back on Thursday. ‘It’s a big office, Jack. I’m sure whoever you spoke to had just got the wrong end of the stick. It’s them that sent her there. I can call them for you, if you—’

‘You’ve been speaking to her?’

I hesitated before I said, ‘Yeah.’

‘Today?’

I pulled my phone from my ear to check for any new missed calls or messages. ‘No. Not today.’ Sarah had sent me only one text message since she’d landed, and that had come in on Sunday afternoon.

It was nearly Tuesday afternoon now.

Forty-eight hours with no communication. Could she really be that busy that in two days she hadn’t found sixty seconds to type me a quick text?

I opened WhatsApp and looked for the double checkmark. There was still only one beside the message I’d sent.

She hadn’t read it yet.

Maybe her phone isn’t working abroad. Or maybe it’s dead and she’s lost her charger. She could’ve forgotten to bring a European plug adaptor and she’s been too busy to find a place where she can buy another one.