6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

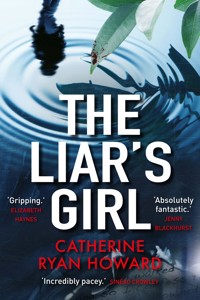

Shortlisted for the Edgar Award, Best Novel 2019 Irish Times' Best Book of the Year, 2018 'Dark, yes, but tender too. The Liar's Girl is tightly plotted and crackles with suspense.' Ali Land, author of Good Me Bad Me 'A killer premise that totally delivers. A creepy, claustrophobic tale that never lets up on the tension while also managing to strike a truly tender note.' Caz Frear, bestselling author of Sweet Little Lies Her first love confessed to five murders. But the truth was so much worse. Dublin's notorious Canal Killer, Will Hurley, is ten years into his life sentence when the body of a young woman is fished out of the Grand Canal. Though detectives suspect they are dealing with a copycat, they turn to Will for help. He claims he has the information the police need, but will only give it to one person - the girl he was dating when he committed his horrific crimes. Alison Smith has spent the last decade abroad, putting her shattered life in Ireland far behind her. But when she gets a request from Dublin imploring her to help prevent another senseless murder, she is pulled back to face the past - and the man - she's worked so hard to forget.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

THE LIAR’S GIRL

Also by Catherine Ryan Howard

Distress Signals

‘Absolutely fantastic. I was gripped the entire way through, can’t recommend it enough…’ Jenny Blackhurst

‘Catherine Ryan Howard is such a skilled storyteller - every setting was evocative, every hook well-placed, every twist expertly-timed. I flew through it! Astonishingly good.’ Jo Spain

‘Gripping.’ Elizabeth Haynes

‘A stand-out book… Real and sympathetic characters, a flawlessly-paced plot and a genuinely original premise. I finished it at 2:00am, my heart pounding!’ Gillian McAllister

‘Slick, smart and stylish... Really clever.’ Holly Seddon

‘The Liar’s Girl is BRILLIANT. [Catherine Ryan Howard has] outdone herself... It’s even better than the Dagger-nominated Distress Signals and that’s saying something!’ Michelle Davies

‘Bloody good… the paciest I’ve read in a long while.’ Sinéad Crowley

‘Distress Signals is a highly confident and accomplished debut novel, impeccably sustained, with not a false note… a psychologically acute portrait of a killer that is genuinely moving. We will hear a great deal more of this author.’ Irish Times on Distress Signals

‘This is Catherine Ryan Howard’s debut thriller, and what a tense, tight, original page turner she’s delivered… Definitely a new, exciting and original author to watch.’ Sunday Independent on Distress Signals

‘Catherine Ryan Howard is an astonishing new voice in thriller writing. Pacey, suspenseful and intriguing, I highly recommend it for a top class page turning read.’ Liz Nugent on Distress Signals

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Catherine Ryan Howard, 2018

The moral right of Catherine Ryan Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 897 4E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 898 1

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To Dad, for publicity services rendered

It’s 4.17 a.m. on Saturday when Jen comes to on a battered couch in a house somewhere in Rathmines, one of those red-brick terraces that’s been divided into flats, let out to students and left to rot.

He watches as her face betrays her confusion, but she’s quick to cover it up. How much does she remember? Perhaps the gang leaving the club on Harcourt Street, one behind the other. Pushing their way through the sweaty, drunken crowds, hands gripping the backs of dresses and tugging on the tails of shirts. Maybe she remembers her friend Michelle clutching some guy’s arm at the end of it, calling out to her. Saying they were moving on to some guy’s party, that they could walk there.

‘Whose party?’ he’d heard her ask.

‘Jack’s!’ came the shouted answer.

It was unclear whether or not Jen knew Jack, but she followed them anyway.

Now, she’s sitting – slumped – on a sofa in a dark room filled with faces she probably doesn’t recognise. The thin straps of her shimmery black dress stand out against her pale, freckled skin and the make-up around her eyes is smudged and messy. Her lids look heavy. Her head lolls slightly to one side.

Someone swears loudly and flicks a switch, filling the room with harsh, burning light.

Jen squints, then lifts her head until her eyes reach a single bare, dusty bulb that hangs from the ceiling. Back down to the floor in front of her. A guy is crawling around on all fours, searching for something. She frowns at him.

This place is disgusting. The carpet is old and stained. There are broken bits of crisps, hairs and cigarette ash nestled deep in its pile. It hasn’t been laid. Instead, the floor is covered with large, loose sections of carpet, ragged and frayed at the edges, with patches of dusty bare floor showing in between. The couch faces a fireplace that’s been blocked off with chipboard, while an area of green paint on the otherwise magnolia chimney breast marks where a mantelpiece once stood. Mismatched chairs – white patio, folding camping accessory, ripped beanbag – are arranged in front of it. Three guys sit in them, passing around a joint.

Another, smaller couch is to Jen’s left. That’s where he sits.

The air is thick with smoke and the only window has no curtains or blinds. The bare glass is dripping with tributaries of condensation.

He can’t wait to leave.

Jen is growing uncomfortable. Her brow is furrowed. He watches as she clasps her hands between her thighs and hunches her shoulders. She shifts her weight on the couch. Her gaze fixes on each of the three smokers in turn, studying their faces. Does she know any of them? She turns her head to take in the rest of the room—

And stops.

She’s seen them.

To the right of the fireplace, too big to fit fully into the depression between the chimney breast and the room’s side wall, stands an American-style fridge/freezer, gone yellow-white and stuck haphazardly with a collection of garish magnets.

Jen blinks at it.

A fridge in a living room can’t be that unusual to her. As any student looking for an affordable place to rent in Dublin quickly discovers, fridges free-standing in the middle of living rooms adjacent to tiny kitchens are, apparently, all the rage. But if Jen can find a clearing in the fog in her head, she’ll realise there’s something very familiar about this one.

She’s distracted by the boy sitting next to her. Looks to be her age, nineteen or twenty. He nudges her, asks if she’d like another drink. She doesn’t respond. A moment later he nudges her again and this time she turns towards him.

The boy nods towards the can of beer she’s holding in her right hand, mouths, Another one?

Jen seems surprised to find the beer can there. Tilting it lazily, she says something that sounds like, ‘I haven’t finished this one yet.’

The boy gets up. He’s wearing scuffed suede shoes with frayed laces, jeans, and a blue and white striped shirt, unbuttoned, with a T-shirt underneath. Only a thin slice of the T-shirt is visible, but it seems the design on it is a famous movie poster. Black, yellow, red. After he leaves, Jen relaxes into the space he’s vacated, sinking down until she can rest the back of her head against a cushion. She closes her eyes—

Opens them up again, suddenly. Pushes palms down flat on the couch, scrambling into an upright position. Stares at the fridge.

This is it.

Her mouth falls open slightly and then the can in her hand drops to the floor, falls over and rolls underneath the couch. Its contents spill out, spread out, making a glug-glug-glug sound as they do. She makes no move to pick it up. She doesn’t seem to realise it’s fallen.

Unsteadily, Jen gets to her feet, pausing for a second to catch her balance on towering heels. She takes a step, two, three forward, until she’s within touching distance of the fridge door. There, she stops and shakes her head, as if she can’t believe what she’s seeing.

And who could blame her?

Those are her magnets.

The ones her airline pilot mother has been bringing home for her since she was a little girl. A pink Eiffel Tower. A relief of the Grand Canyon. The Sydney Opera House. The Colosseum in Rome. A Hollywood Boulevard star with her name on it.

The magnets that should be clinging to the microwave back in her apartment in Halls, in the kitchen she shares with Michelle. That were there when she left it earlier this evening.

Jen mumbles something incoherent and then she’s moving, stumbling back from the fridge, turning towards the door, hurrying out of the room, leaving behind her coat and bag, which had been underneath her on the couch all this time.

No one pays any attention to her odd departure. The party-goers are all too drunk or too stoned or both, and it is too dark, too late, too early. If anyone notices, they don’t care enough to be interested. He wonders how guilty they’ll feel about this when, in the days to come, they are forced to admit to the Gardaí what little they know.

He counts to ten as slowly as he can stand to before he rises from his seat, collects Jen’s coat and bag and follows her out of the house.

She’ll be headed home. A thirty-minute walk because she’ll never flag down a taxi around here. On deserted, dark streets because this is the quietest hour, that strange one after most of the pub and club patrons have fallen asleep in their beds but before the city’s early-risers have woken up in theirs. And her journey will take her alongside the Grand Canal, where the black water can look level with the street and where there isn’t always a barrier to prevent you from falling in and where the street lights can be few and far between.

He can’t let her go by herself. And he won’t, because he’s a gentleman. A gentleman who doesn’t let young girls walk home alone from parties when they’ve been drinking enough to forget their coat, bag and – he lifts the flap on the little velvet envelope, checks inside – keys, college ID and phone too.

And he wants to make sure Jen knows that.

Mr Nice Guy, he calls himself.

He hopes she will too.

Will, now

The words floated up out of the background noise, slowly rearranging the molecules of Will’s attention, pulling on it, demanding it, until all trace of sleep had been banished and he was sitting up in bed, awake and alert.

Gardaí are appealing for witnesses after the body of St John’s College student Jennifer Madden, nineteen, was recovered from the Grand Canal early yesterday morning—

It was coming from a radio. Tuned to a local station, it sounded like; a national one would probably have reminded listeners that the Grand Canal was in Dublin. The rest of the news bulletin had been drowned out by the shrill ring of a telephone.

As per the rules, the door to Will’s room was propped open. He leaned forward now until he could see through the doorway and out into the corridor. The nurses’ station was directly opposite. Alek was standing there, holding his laminated ID to his chest with one hand as he reached across the counter to pick up the phone with the other.

In the moment between the silencing of the phone’s ring and Alek’s voice saying, ‘Unit Three,’ Will caught another snippet – head injury – and by then he was up, standing, trying to decide what to do.

Wondering if there was anything he could do.

Unsure whether he should do anything at all.

He decided to speak to Alek. They were friends, or at least what qualified as friends in here. Friendly. Will waited until the nurse had finished on the phone before he crossed the corridor.

‘My main man,’ Alek said when he saw him. ‘They said you were sleeping in there.’ Alek was Polish but losing more and more of his accent with each passing year. Five so far, he’d been working here. The last four in Unit Three. ‘You feeling okay?’

‘I was just reading,’ Will said. ‘Must have dozed off.’

‘Anything good?’

Will shrugged. ‘Can’t have been, can it?’

Alek picked a clipboard up off the counter and started scanning the schedule attached to it. ‘Shouldn’t you be in with Dr Carter right now?’

The news bulletin had moved on to the weather. Rain and wind were forecast. In keeping with tradition, the disembodied voice joked, tomorrow’s St Patrick’s Day parade would be a soggy one.

Will hadn’t realised that was tomorrow. It was hard to keep a hold of what day of the week it was, let alone dates and months.

‘That got moved to three,’ he said. ‘I think because she has a court thing …?’

Alek looked up from the clipboard. Patients shouldn’t know anything about what the staff did outside of the high-security unit but Will had just revealed to Alek that he did.

If Alek was going to reprimand Will for it, now would be the time.

But Alek let the moment – and the breach – pass.

He treated Will differently to the others. They all did. That’s how Will knew his counsellor had a court appearance in the first place. She’d let it slip at the end of their last session when she was advising him of the schedule change, less careful with him than with her other patients. He appreciated this differential treatment and never took it for granted. He felt like he’d earned it over the last ten years. He’d never caused them any trouble. He’d always done whatever he was told.

And now he was going to have to take advantage.

Will checked the corridor. No one else was around. Mornings were for counselling and group sessions; Will wouldn’t be here either if it wasn’t for Dr Carter’s trip to court.

It was pure chance he’d heard the bulletin.

‘Ah, Alek,’ Will started. ‘The radio—’

‘Oh, shit.’ Alek dropped the clipboard onto the counter and moved in behind it, reaching up for the little transistor radio sitting on the top shelf. The radio clicked off. ‘Sorry. That isn’t what woke you up, is it?’

‘No, no,’ Will said. ‘It’s fine. I was just going to ask you – were you listening to the news just now?’ Alek raised an eyebrow, suspicious. ‘I thought I heard something there about the, ah, about the canal?’

A beat passed.

Alek picked up his clipboard again. ‘I wouldn’t worry about it, man.’

‘Do you know what happened?’

‘Why do you want to know?’

‘I was just wondering …’ Will paused, swallowed hard for effect. ‘Was it about me?’

‘About you?’ Alek shook his head. ‘No. What made you think that?’

‘We’re coming up on ten years, aren’t we? I thought maybe it was something to do with that.’

‘It’s not.’

‘No?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sure?’

Alek looked at him for a long moment, as if trying to decide something. Then he sighed and said, ‘That was Blue FM. They do their news at ten to.’ He met Will’s eyes. ‘It’s almost one. I’ll put on a different channel.’

‘Thanks,’ Will said. ‘I really—’

‘Don’t thank me, because I didn’t do this.’ He reached up and switched the radio back on, moving the dial until he found a station promising a lunchtime news bulletin after the break. Then he took a seat behind the counter and pushed a leaflet about the benefits of mindfulness towards Will. ‘Pretend you’re reading that, at least.’

It was the top story.

The leaflet’s text blurred in front of Will’s eyes as he banked each detail. Jennifer Madden. A St John’s College student. A first-year, going by her age. Found in the Grand Canal near Charlemont Luas station yesterday, having last been seen at a house party in Rathmines on Saturday night. Gardaí are treating her death as suspicious. Believed to have suffered a head injury before going into the water. Anyone with information should call the incident room at Harcourt Terrace.

And thanks to the weather report, Will could add another detail: this had happened a few days before St Patrick’s Day.

Warm relief flooded his veins.

Finally, after all these years, it was happening.

And just in the nick of time, too.

‘Alek,’ he said, leaning over the counter, ‘I need to speak to the Gardaí. Right now.’

Alison, now

They came to my door the morning after Sal’s dinner party.

I was still suffering. It’d been a St Patrick’s Day one, held in my honour, me being the sole Irish member of our group. Sal and I had drifted into a motley crew of ex-pats who’d bound themselves to an arrangement to get together once every couple of months, taking it in turns to be Chief Organiser. There was a core group of six or seven who could be relied upon to show up, and then several more who occasionally surprised us. We called ourselves ‘The EUs’ because while we could claim nationalities in nine different countries, they were all within a train-ride or Ryanair flight of our adopted home. One of Sal’s goals in life was to infiltrate Breda’s American ex-pat community and convince at least some of them to join our gang.

I’d arrived early to help Sal and Dirk set up, but was forbidden from doing anything except sit on their sofa holding a champagne flute of something Instagram had apparently claimed was called a Black Velvet. It looked a bit like bubbly Guinness. I don’t actually like Guinness, but I kept that titbit to myself. Instead, I watched as Sal, looking like a 1950s housewife in her belted green dress, bright red lipstick and neat blonde bun, unloaded a bag of garish decorations onto her dining table: gold confetti, rainbow-coloured novelty straws and serviettes with cartoon leprechauns on them.

‘Classy,’ I remarked.

‘They are compared to what else was on offer,’ Sal said. ‘You can thank your lucky charms I didn’t get any hats.’

‘You know “lucky charms” is more of an American thing, right? A breakfast cereal? We don’t actually say that.’

‘Is a rant about “Patty’s Day” coming next?’

‘No, I’ll wait until everyone else gets here for that. They all need to hear it.’

Sal rolled her eyes. ‘Something to look forward to, then.’

‘I still can’t believe you’re throwing a dinner party,’ I said. ‘Even if it is one with novelty straws and leprechauns. You’re such a grown-up.’

‘Don’t remind me.’ Sal paused to appraise her table. It was set for twelve, an impressive showing for The EUs. ‘We own white goods, Ali. White goods. And then there’s this bloody thing.’ She held up her left hand, wiggling her ring finger. The platinum band glinted under the ceiling lights. ‘I’m still not used to it.’

They’d only been married a month. Dismissive of tradition, Sal had had her wedding here, forcing her family to travel over from London. The skin on her forearms was still lightly browned from their honeymoon in the Maldives, and I hadn’t yet worked my way through all the luxury toiletries she’d swiped for me from the bathroom of the five-star resort they’d stayed in. My bridesmaid dress was still at the dry cleaner’s.

The doorbell went then and Sal hurried out of the room to answer it. I wondered where Dirk was, then realised he must be the one making all the clattering sounds coming from the kitchen.

I took a tentative sip of my drink and discovered it was, literally, bubbly Guinness. Guinness topped with champagne. A crime against both substances. I was grimacing at the sour aftertaste when the door to the living room opened and an attractive man I’d never seen before walked in, closely followed by Sal, smiling demonically and making suggestive faces at me behind his back.

‘This,’ she announced, ‘is Stephen.’

I knew what was coming before she said it: Stephen was Irish too. He had that look about him. Not the red-headed, freckled one we’re famous for, but the more typical reality: pale skin, blue eyes, black hair. Sal had found another one of us and she seemed very excited about it. As she explained that he was a colleague of Dirk’s, that he’d just moved here a fortnight ago, that he didn’t really know anyone yet but we’d snared him for our group now and did I mind sharing my Guest of Honour spot with him for the evening, I realised why: she thought she’d found him for me.

Groaning inwardly, I stood up to shake his hand and exchange hellos.

‘Drink?’ Sal asked him. ‘What’ll you have?’

Stephen looked to my glass, then to me, and I shook my head as much as I could before Sal would see.

‘How about a beer?’ he said.

A South Dublin accent. Our age, as far as I could tell. Thirty-ish. And if he worked with Dirk at the software company, that meant he likely had a college degree …

I knew where this was going.

I had to concentrate on keeping a pleasant expression on my face.

‘You won’t have one of those?’ Sal pointed at my glass. ‘It’s a Black Velvet. They’re delicious.’

‘I, ah, I don’t drink Guinness,’ Stephen said. ‘That’s why I had to leave Ireland, actually. They found that out.’

I forced a laugh. Sal’s smile faltered, because although neither Stephen nor I knew this yet, her main was Guinness stew.

They settled on a Heineken and Sal left to fetch it, leaving Stephen and me to have the standard So, You’ve Just Met a Fellow Irish Person Abroad talk. He confirmed my suspicion that he was from South Dublin, told me he’d spent the last three years in Abu Dhabi and that, this time around, he was trying to avoid repeating what he’d done out there: so assimilated himself within the Irish ex-pat gang that he’d ended up playing GAA every weekend and only ever drinking in an Irish pub that could’ve been called Six Degrees of Stephen’s School Friends. I told him I was from Cork, that I’d been in the Netherlands nearly ten years, that I worked in Ops Management for a travel company, and that Sal and I had met in the laundry room of our student accommodation in Den Hague. We’d recognised the confused look on each other’s faces as a shared inability to process the instructions posted above the machines, and been friends ever since.

‘Don’t tell anyone,’ Stephen said, ‘but the guys at work were saying “den hag” for three days before I realised that meant The Hague.’

I smiled. ‘Don’t worry about it. When I first got here, I thought Albert Heijn was a politician.’ Stephen raised his eyebrows. ‘It’s a chain of supermarkets,’ I explained. ‘The supermarket I was going to, on a regular basis, for at least a month before I put two and two together. Dutch sounds nothing like it looks, half the time. To us, anyway. That’s the problem.’

‘Do you speak it?’

‘A little. Very little. Nowhere near as much as I should. Everyone speaks English here, so you get lazy. And Suncamp are a British company. It’s all English at work.’

‘Did you go to college here then or …?’

‘I went here.’ I took another sip of my drink, forgetting that it tasted like something they make you drink in a hospital before they scan your intestines. He hadn’t spoken by the time I’d forced a swallow, so I asked, ‘Where did you go?’ even though I had already guessed the answer and I didn’t want to hear it said out loud, didn’t want to hear those three bloody words—

‘St John’s College.’

All I could do in response was make a hmm noise.

‘I could walk there from my parents’ house,’ Stephen said, ‘and both of them went there, so I really didn’t have a choice.’

I fixed my eyes on my glass. ‘What did you study?’

‘Biomedical Science.’ He paused. ‘Class of 2009.’

I did the sums: he’d have been in his third year back then so. But I didn’t need to do them. That tone he’d used, an odd mix of pride and solemnness. The dramatic pause. The fact alone that he’d felt the need to tell me when he’d graduated.

It all added up to: Yes, I was there then. I was there when it happened.

‘Do you get back home much?’ he asked me.

‘Sorry,’ I said, standing up, ‘but while I have the chance, I’m going to find a potted plant to dump the rest of this concoction in. Back in a sec.’

And that was it. The swift and sudden end of Sal’s dream that Stephen could be the man for me coming before she’d even returned with his drink.

I’d never be able to tell her why.

Not the real reason, anyway.

For the rest of the evening (through three courses, goody-bags consisting of packets of Tayto and Dairy Milk bars, and an hour’s worth of Father Ted YouTube clips because trying to describe it to our mainland-Europe diners wasn’t getting us anywhere), I concentrated on enjoying myself, thankful that Sal’s never-ending hostess duties prevented her from grabbing me for a sidebar.

She did it via WhatsApp the next morning instead.

What happened with Stephen? I brought him for you and you barely spoke to him! Since I know you’re going to give me some I’m-concentrating-on-my-career BS now and I’M going to have to give YOU the Cat Lady talk again, I’ve just saved us both the bother and given him your number. He was STARING at you all night (not in a serial killer way). In other news, am DYING. May actually already be dead. Haven’t even gone into the kitchen yet. Too afraid. Sent D out for caffeine and grease. Was good, though, right? Send proof of life. X

I read it at my kitchen table, nursing my second cup of black coffee while my stomach gurgled and ached, protesting at last night’s abuse.

So Sal had given Stephen my number. How in absolutely no way surprising. When it came to such stunts, the girl had prior. I wasn’t annoyed, but I feared Sal would be soon. Because if Stephen did call or text, I’d just deploy my usual, terminally single strategy: say I was busy until next week, cancel those plans last minute and then repeat as required until he got annoyed and gave up. It wasn’t a great plan, but it beat having to tell him – or Sal – the truth further down the line.

I typed a quick reply, assuring Sal that I was indeed alive, thanking her for the party and promising I’d call her later. I didn’t mention Stephen at all.

I’d just pressed SEND when I heard the knock on the door.

I thought it was the postman with a parcel. Or that there was a new guy bringing my neighbour’s weekly grocery delivery, and he’d accidentally come to the wrong house. But huddled on my doorstep, heads dipped beneath the gutter’s narrow overhang in a futile attempt to shield themselves from that morning’s heavy rain, were two men about to introduce themselves as members of An Garda Síochána.

The younger one wasn’t much older than me. Tall, with a thick quiff of reddish-brown hair and a beard to match. Bright green eyes. Not unattractive. He pulled a small leather wallet from an inside pocket and flipped it open, revealing a gold Garda shield and an ID.

Garda Detective Michael Malone.

The other one I recognised, even though I’d only spent a few hours with him, one afternoon almost ten years ago. The sparse tufts of grey hair left on the sides of his head had been made thinner still by the rain, and patches of bald, pink scalp were shining through. He was turned away, eyes on something further down the road, hands stuck in his pockets.

Garda Detective Jerry Shaw.

‘Alison Smith?’ Malone asked.

‘What’s wrong?’ I said. ‘Is it …? Are my parents—’

‘Everyone’s fine. Everything’s okay.’ He glanced down the hall behind me. ‘Can we come in? There’s something we need to talk to you about. Should only take a few minutes.’ He flashed a smile, but if he was going for reassurance he fell way short of the mark.

Two Irish detectives. Here at my door in Breda.

And one of them was Detective Jerry Shaw.

This could really only be about one thing, but I asked the question anyway.

‘What’s this about?’

Shaw finally turned towards me. Our eyes met.

‘Will,’ he said.

Alison, now

I led them down the hall, into the kitchen, suddenly conscious of my loose grey sweatpants and misshapen old T-shirt, the dregs of last night’s make-up smudged around my eyes. I’d hit my bed around four, just about managing to kick my shoes off before I fell asleep. Turns out that after you’ve had five of them, Black Velvets don’t taste so bad after all.

While my back was turned to the detectives, I licked a finger and swiped underneath my eyes as discreetly as I could. I tucked my hair behind my ears and ran my tongue over my teeth. I hadn’t even brushed them yet.

I glanced down at my sweatshirt. No discernible stains. Good.

I pointed them to my kitchen table. My cup and phone were still sitting there, marking my spot. The detectives took the two seats across from it.

The pot of coffee I’d brewed half an hour before was still half-full. I offered some and both men gratefully accepted a cup. While I watched Shaw spoon a genuinely alarming amount of sugar into his, Malone started telling me about how they were both exhausted because they’d caught the dawn flight out of Dublin and then driven here from Schiphol in a hired car.

‘Has he been released?’ I asked. I’d interrupted a complaint about the lack of signage on local roads, but I just couldn’t wait any longer.

Shaw said, ‘No.’

This was the first word he’d spoken since he’d come inside.

My shoulders dropped. I’d been tense with this possibility ever since I’d pulled back the front door.

‘He’s still in the CPH,’ Malone said. ‘The Central Psychiatric Hospital. Although he is scheduled to be moved to Clover Hill next month.’

‘The holiday’s finally over,’ Shaw said.

‘Clover Hill is a prison,’ Malone explained. ‘It’ll be a big change for him.’

‘Sorry if this is a stupid question,’ I said, ‘but shouldn’t he be in prison already? Why is he in a hospital?’

‘A psychiatric hospital,’ Malone corrected. ‘It’s still secure, but he can receive treatment. At some point – very early on in his incarceration, I think – it was decided that his needs would be better served there.’

‘He was getting treatment? What for?’

Shaw snorted. ‘For being a serial killer, love.’

Malone said to me, ‘Will was very young when he entered the system, and he was a … Well, let’s just say he was very much a unique prisoner. The Prison Service decided that the CPH was the best home for him. Until now, at least.’

‘Why are you here?’

The two detectives exchanged a glance. Then Malone asked me if I kept up with the news at home.

‘No,’ I said. ‘To be honest, I couldn’t even tell you who’s Taoiseach.’

‘Well,’ Shaw said, ‘you’re not missing anything there, love, let me tell you.’

‘What about your parents?’ Malone pressed. ‘Might they mention things to you?’

‘If you mean deaths in the parish and the year on next-door’s car, then yeah. As for actual news, no.’ I looked from one detective to the other. ‘Why don’t you just tell me what’s happened because obviously something has?’

‘We found a body,’ Shaw said. ‘In the Grand Canal. Nineteen-year-old girl. A student at St John’s.’

His tone was so matter-of-fact that it took me a second to put the words together and process what he’d actually said. Malone turned to glare at his colleague but all he got in response was Shaw picking up his coffee and taking a grotesquely noisy slurp.

‘What happened?’ I asked. My mouth was suddenly bone dry. ‘What happened to her?’

‘We’re still trying to—’ Malone started.

‘Stunned,’ Shaw said, ‘it seems like. By a blow to the head. Probably went into the water unconscious then. Cause of death was drowning.’

A cold brick of dread settled in my stomach.

Malone leaned forward. ‘We got a report last Saturday morning. A pair of joggers were passing under the Luas tracks at Charlemont when they spotted something in the water. It was the body of Jennifer Madden, nineteen. A student at St John’s since September. She’d last been seen at a party in Rathmines the night before.’

The weekend before St Patrick’s Day, then.

I said, ‘Could it just be a coincidence?’

Malone shook his head. ‘Doesn’t look like it, no. Jennifer … She, ah, isn’t the first. She’s the second. Louise Farrington was found in January, by Baggot Street Bridge. It looked like a tragic accident, at the time. But now with this second case … Well, the dates fit.’

‘Why did you think the first one was an accident?’

Malone went to answer but Shaw cut in. ‘Because that’s what it looked like.’

‘What’s important,’ Malone said, shifting his weight, ‘is that we don’t think that any more.’

‘Someone’s copying him,’ I said.

They both nodded. Shaw said, ‘Seems that way.’

I placed my palms flat on the table in front of me and willed the walls to slow and still.

Then I asked the detectives if they had any idea who.

‘We’re following a number of leads,’ Malone said. ‘One of them is the reason we’re here.’

I honestly had no clue what was coming next. I hadn’t lived in Ireland in nearly ten years. I hadn’t been in Dublin since the weekend of Will’s arrest. I wasn’t in touch with anyone from home except for my parents.

How had any lead led back to me?

‘It seems,’ Malone said, ‘that Will heard a news report about Jennifer the day after her body was found. According to a nurse on staff at the CPH at the time, Will became upset, and asked if he could make a call to the Gardaí. He said he needed to speak with us. We’ – Malone indicated himself and Shaw – ‘went out there yesterday. To the CPH.’

‘You’ve talked to him?’ My mind was racing. How was he? How does he look? What did he say? Is he sorry? Did he tell you why? I had to concentrate in order to pluck a single coherent thought from the noise. ‘But he can’t know anything. He’s been inside, all this time. Unless … You don’t think …? You don’t think he was working with someone back then, do you? That there were two of them? And this is the other guy, back at it now? Is that a possibility?’

‘Why would you ask us that?’ Shaw was watching me closely. ‘Do you think that’s a possibility?’

I met his eyes. ‘I think I learned ten years ago that anything is possible.’

‘But,’ Malone said, ‘specifically.’

I looked to him. ‘I can’t say I remember anything that made me think that, no. But then I didn’t think that my boyfriend was a serial killer either.’ I stopped to take a breath, to steady my voice. ‘What did Will say?’

I hadn’t said his name in so long the sound felt like a foreign object in my mouth, one with sharp edges that pressed painfully against the soft skin of my throat.

‘Well,’ Malone said, ‘that’s just it. When we met with him, Will told us he did have information that could potentially assist us, but that he wouldn’t tell it to us.’

‘That’s ridiculous.’ I looked from one man to the other. ‘Why would he bother telling you he knows something and then refuse to say what it is when you get there? That doesn’t make any sense.’

‘What I meant was,’ Malone said, ‘he wouldn’t tell us.’

Shaw leaned back in his chair, folded his arms across his chest and mumbled something under his breath.

I thought I heard waste of time.

‘Admittedly,’ Malone said, ‘it’s unlikely that Will would have any valuable information. But that doesn’t change the fact that he does have a relevant role here, even if it’s one he hasn’t actively participated in. Our working theory is that this is a copycat. If that’s the case, by this time next week, we’ll have another dead college student on our hands. A third innocent victim, unless we catch this guy. And if we don’t do everything we can possibly can, if we don’t explore every last lead, however small or unlikely, then we will have that girl’s death not just on our hands but on our consciences, too.’

He’d lost me.

I said, ‘I think I’ve missed a step …?’

‘We can’t force you to do this,’ Malone said. ‘So we’re here to ask.’

‘Ask me w—’ I stopped, realising.

No. No way. Absolutely not.

And then I said those words out loud.

‘How about you have a think about it?’ Malone said.

‘I don’t need to.’

‘If it’s the press you’re worried about, that won’t be an issue.’

In my mind’s eye, I saw a flash of a tabloid newspaper’s front page, one side taken up with a picture of me in cut-off shorts and a bikini top, taken on a girls’ holiday to Tenerife the summer before I’d started college. The other side was all headline. SERIAL KILLER’S KILLER GIRL.

They got the photo from my Facebook page, which I’d only signed up for a couple of weeks before Will’s arrest. This was before the press copped on to the fact that people’s social media profiles were treasure troves of personal information just waiting to be mined, so it was far more likely that a friend I was connected with on the site had screenshot the photos and sold them.

‘We’ll take steps to ensure that your involvement in this will be kept top secret,’ Malone was saying. ‘We’ll get you in and out before anyone even knows you’re in Dublin.’

‘No,’ I said again.

‘Well,’ Shaw said, hoisting himself up out of his chair, ‘thanks for the coffee.’ He looked at Malone with an expression that said he’d known all along it was going to go this way.

‘Why don’t you take the day?’ Malone said, standing up too. ‘Like I said, we can’t force you to do this. But we don’t know what he might say. It might be important. It might give us the break we need.’ He took a business card from a pocket, placed it on the table. ‘We need to know no later than four this afternoon, Alison, so you can fly back with us tonight. If you say yes, you’ll be meeting with Will at the CPH first thing tomorrow morning. All the necessary arrangements are already in place.’

Alison, then

‘Liz?’ I whispered. ‘Are you awake?’

The light was faint and blue-grey. Morning, then, but very early, still. The room was chilly – we’d turned the dial on the thermostat all the way to the snowflake symbol before we’d gone to bed – but the reddened skin on my back and arms still burned hot, every contact with the sheet like the rough scratch of sandpaper. Various items of summer clothing and accessories were taking shape in the shadows, messy little mounds on the tiled floor. I could see the neon strings of bikini tops, the tie-dyed print of cover-ups we’d bought from a beach stall, straw hats, damp towels, plastic flip-flops. Empty or half-drunk plastic water bottles of various sizes stood like an audience on top of the scratched chest of mahogany drawers stood against the opposite wall. Outside, the resort was uncharacteristically silent but for the clicking call of the cicadas.

In the other single bed, Liz began to stir.

‘I don’t feel well,’ I said into the semi-darkness.

Her first response was something indecipherable, her voice thick with sleep. But then she rolled over to face me. ‘What time is it?’ She swiped at her hair, pushing wayward strands of it out of her eyes. ‘Ali?’ Liz raised herself up onto her elbows. ‘What’s wrong?’

I was sitting up on the edge of my bed, arms wrapped around my stomach, hunched over, wincing as a sharp pain bisected my abdomen from hip to hip. It’d started a couple of hours ago, just brief stabs at first, but after a couple of trips to the bathroom that I could only describe as traumatic, it was now worse and near constant. I’d also broken out in a cold, clammy sweat.

I felt awful.

‘I think I might have food poisoning,’ I said miserably.

‘What? Why?’ Liz sat up, swinging her spindly legs onto the floor. ‘Have you been sick?’

‘No, but I think I’m going to be.’

‘And have you been—’

‘Yeah.’ I made a face. ‘Twice.’

‘Oh boy.’

‘I think it was the burgers. I was the only one who had a chicken one, wasn’t I? But’ – I inhaled sharply as an especially painful pinch gripped some part of my insides – ‘those Sambuca shots probably didn’t help. And then there was the ice. Do they make that with tap water? Are you supposed to drink the tap water here?’

‘We’re in Tenerife,’ Liz said, ‘not Calcutta.’

Our third day in Playa de las Americas was dawning. Only our third day and here I was, doubled over with stomach pain. Presumably still asleep elsewhere in the apartment were another two girls from our class, and elsewhere in the resort were the remaining eight members of the group. So far we’d spent our time sunbathing, drinking and overspending, and then sleeping those activities off until we were ready to go again. The quintessential post-Leaving Cert holiday.

I’d actually been dreaming that I’d accidentally burned through my entire fortnight’s budget in just the first couple of days, and thought the panic of this is what had woken me up in the middle of the night. Then I’d felt the shooting pain, the sudden movement in my gut, and realised I had real problems.

‘Warning,’ Liz said, standing up. ‘I’m turning on the light.’

There was a click, followed by a blinding glare. When my eyes adjusted, I saw that Liz was bent over, rummaging in her suitcase. It was lying open on the floor where she’d left it on the first day. Her wavy blonde hair was a tangled mess, her eyes still rimmed with the thick eyeliner and the T-shirt her drunk self had pulled on to sleep in was inside-out, the label and seams clearly visible. She found a small box of something – tablets – and straightened up, bringing the box close to her face to read the label.

‘These are the job,’ she said, throwing it to me. She selected one of the water bottles and passed it to me. ‘Take two of them.’

‘What are they?’

‘Imodium. They keep things in and they keep things down.’

I swallowed the tablets with a swig of water.

Liz left the room, returning half a minute later with the large plastic dish that had been sitting in the sink, clean towels and a bottle of sports drink, ice-cold from the fridge. She set them all down within my easy reach. Then she wet a facecloth in the bathroom and wiped my forehead and cheeks with it, tying my hair back from my face with an elastic band she’d had in hers.

‘God,’ she said, ‘you look awful.’

I smiled weakly. ‘Thanks.’

‘Any time.’ She patted my shoulder, then jerked her hand away. ‘Jesus, the heat off that!’

‘Sunburn,’ I said. ‘Unrelated.’

‘Unless you have heat stroke.’

‘Does that make you …?’

‘I don’t know. Maybe. Do you want me to put on some more after-sun?’

‘No, no. It’s okay.’

While I sat perched on the edge of my bed, clenched and tense, Liz worked around me to straighten my pillows and smooth out the crumpled sheets. When she was done I lay back down, drew my knees up to my chest to help with the pain and closed my eyes.

I spent the rest of the day like that.

And then three more days after that the very same way.

The pain did dull to mere discomfort, but I was hot and sweaty and sick, and too much of all those things to lift my head up off the pillow. I faded in and out of sleep. I couldn’t eat and only drank because Liz would appear every couple of hours with a bottle with a straw stuck in it, forcing me to take a few sips. Had this happened to me at home, in my own room with my mother nearby, it would’ve been horrible but tolerable. Here, hundreds of miles away, on a thin mattress on a hard, uncomfortable bed in a bare-bones holiday apartment, it was nightmarish.

On the second evening Liz went to reception and arranged for a visit from a local doctor, who took my temperature, wrote me a prescription and told Liz to start feeding me bananas. That’s what she said, anyway. I didn’t understand much of what he’d muttered in Spanish to me, but I got the feeling he was bemused more than anything. I guess he saw plenty of eighteen-year-old Irish girls away from home for the first time whose bodies quickly baulked at their bad decisions.

I pleaded with Liz to leave me to suffer alone, but she refused to go further than the resort’s swimming pool without me, and she only went there for short periods while I was asleep. Instead, she brought me magazines, played cards with me and made sure I was drinking my water and eating my bananas. She had housekeeping bring fresh sheets and she dragged the TV in from the living room, although we couldn’t find anything on it in English except BBC News.

The other girls wandered in and out, wrinkling their noses while they made sounds of sympathy, but they didn’t let my sickness get in the way of their holidaying. I was vaguely mad at them for doing that and angry at Liz for not doing it at all.

‘I’m ruining your holiday,’ I said to her. We’d been living for this fortnight for nearly nine months and now, thanks to me, she was spending it in the apartment. ‘You should go out with them. Go out tonight. I’ll be fine. Really.’

‘Are you serious?’ She rolled her eyes. ‘If I was sick and you left me by myself, I’d bloody murder you. We’ll both go out when you’re feeling better.’

‘But we don’t know when that’ll be. You could miss this entire holiday.’

‘Eat your bananas.’

The Plague, as we started calling it, lasted nearly four nights and days. I’d spent my first forty-eight hours in Tenerife sunburnt and hungover, so that was pretty much the entire first week chalked down to a loss. The second one was great, and I flew back to Cork with a tan, fabulous memories and plenty of group photos I didn’t feel comfortable showing my parents, but I still felt bad that I’d reduced Liz’s holiday by half.

I didn’t even mention I’d been sick until I was safely home. My mother’s open mouth and eyes grew bigger and bigger while I gave her all the ghastly details. She wasn’t at all impressed that I hadn’t called to tell her while it was happening, and she was convinced that it was alcohol, not food, that had caused the problem, even though I pointed out that I didn’t think that was medically possible.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘aren’t you lucky you had Liz? She sounds like a right little Florence Nightingale.’ Then she muttered, almost to herself, ‘I didn’t know the girl had it in her.’

——

The summer that starts with the Leaving Cert exam and ends with the publication of their results – which alone will determine our college places – is the most glorious one of all for Irish teenagers. The worst is over; school’s out for ever. College and adult life await. It’s the only one filled with possibility and adventure, but not yet sullied by reality. Anything could happen yet.

But there’s a price to pay: it rushes by. One minute it was all stretched out ahead of us, the next it was a Wednesday in the middle of August and the college offers were coming out.

I was already awake when my phone began to chirp at 5:55 a.m. I’d barely slept, and whenever I had I’d dreamed of disappointment.

I reached for my laptop, fully charged and waiting for me beside the bed. I booted it up, navigated to the CAO homepage and entered my log-in details. By then it was 5:56 a.m.

The laptop’s fan buzzed and whirred, as if protesting at being woken up at this ungodly hour on a summer’s morning. The clunky machine was years old, on its last legs. I’d been dropping hints to Mam and Dad for months, cursing the thing every time it couldn’t handle new software or it failed to save my work. I hit Refresh now because leaving it idle was the quickest way to get it to freeze up and I just couldn’t deal with that this morning on top of everything else.

5:57 a.m.

I felt sick to my stomach, a hangover without the headache. What if I didn’t get in? I could barely remember now what I’d put down as my second choice, symptomatic of my refusal to accept that I’d ever have to do it. If I didn’t get in, I’d repeat. That was the only option. Do the Leaving Cert all over again, try again next year.

Please God, though, don’t let me have to do that.

5:58 a.m.

The house was silent. I’d warned Mam and Dad not to get up, promising I’d wake them when the results were posted. There was just no point in us all getting up for six, especially if it was bad news.

The truth was, I wanted to find out by myself. I wanted to be by myself with it, just for a minute, whether it was good or bad.

5:59 a.m.

I wondered where Liz was checking hers. Probably sitting in bed with her computer, like me. Only knowing Liz, once she saw them, she’d roll over and go back to sleep. She hadn’t even bothered going into school the week before to get her exam results. She’d just checked them online and then headed for the pub, cool as a cucumber, bemused at me when I said she was missing out on a rite of passage, on that moment of opening the envelope, on seeing the grades slide out.

‘I just don’t need all the amateur dramatics,’ she’d said. ‘The day my brother got his there was a full-on performance going on outside the school gates. I just can’t be arsed with that.’

I thought the real reason might be that she didn’t want to have to perform if things didn’t go well for her.

I’d gone in.

6:00 a.m.

Time. Heart thundering in my chest, I hit Refresh again.

First round offer: English Literature, St John’s College Dublin (SJC0492).

I leapt out of bed so fast I nearly sent the laptop crashing onto the floor. I ran out of my room and across the hall into Mam and Dad’s room, ready to burst out, ‘I got in!’ at the top of my lungs – but their bed was empty. I went back out into the hall, saw the bathroom door standing open, the light off.

Where were they?

I heard it then: muffled voices a floor below me. They were up already.

I raced downstairs and into the kitchen with a flourish, pushing the door open so fast that it swung back and hit off the wall with a clatter. They were at the table, both still in their pyjamas. Dad was sitting down and Mam was standing over him, about to fill his mug with coffee from the machine. They looked up at the noise, then at me with raised eyebrows.

I indulged myself with a dramatic pause before yelling, ‘I’m going to St John’s!’

She squealed. He started clapping.

‘Brilliant,’ Mam said. ‘I knew you’d do it.’

Dad got up and patted me on the back. ‘Well done, well done.’

‘What are you guys doing up, though?’ I felt breathless with adrenalin. ‘I told you there was no point in us all being up at this hour.’

‘I had to.’ My father pushed his glasses up his nose. ‘I wanted to know sooner rather than later whether or not I have to remortgage the house. Is it too late to change your mind and go to UCC, do you think?’

This had been his running joke all summer. All year, as a matter of fact. If I went to University College Cork, I could live at home. St John’s meant campus accommodation fees, to the tune of nearly six thousand euro per academic year.

A bottle of Buck’s Fizz and three champagne flutes appeared.

‘Mam,’ I said, ‘it’s six in the morning.’

‘It’s only fizzy orange juice, love. You’ll be out tonight drinking shots of God knows what.’

‘Paint stripper,’ my father said.

‘I’m sure you can manage a glass of this.’

I rolled my eyes and took a sip.

‘We got you a little present.’ My father moved back the dining chair next to his and lifted a huge box up onto the table. It wasn’t wrapped, but there was a red ribbon tied around it.

All I had to see was the Apple logo and I gasped. The drink nearly flew out of my hand. My mother saw this happening and took it from me.

‘What?’ I pulled the box towards me. ‘No way. No way.’

‘She seems more excited about this than St John’s,’ my mother said wryly.

‘Look after it,’ Dad said to me. ‘And use it for studying.’

‘I will, I will. Thanks, Dad.’

‘Your mother did the bow.’

She rolled her eyes. ‘And I made sure he got the right one, more importantly.’

My phone beeped with a text message.

‘Liz,’ I said, looking at the screen. The message just said, CALL ME.

‘Oh – Liz.’ My mother was pouring a glass for my father now. ‘How did she get on, I wonder?’

‘I’m about to find out.’

I took my phone out the back door and into the garden, stepping carefully onto the patio in my bare feet. The sky was clear – it was going to be a gorgeous day – but the garden was in cold shadow, the sun still hidden behind the house.

I selected Liz from my speed-dial list and put the phone to my ear. It only rang once before I heard her voice saying tonelessly, ‘I didn’t get in.’

‘What?’

‘Don’t make me say it a second time.’

I didn’t understand. We had a plan: Liz and I, together at St John’s. I was going to do English Literature and she was going to do English and French. We were going to share an apartment on campus. We were going to have the time of our lives living in Dublin. We’d been talking about it for years, planning every detail for months.

A week ago, we’d celebrated us both getting enough Leaving Cert points, at least based on what we could guesstimate from last year’s threshold for entry. I had a few more than Liz, but then the course I was hoping to get demanded a few more. For all our stress and anxiety, neither of us truly believed we wouldn’t end up with what we wanted when the college offers came through today: a place in St John’s.

‘You mean you didn’t get your first choice?’ I said. Both of us had put down more than one course at St John’s, just in case.

‘No,’ Liz said. ‘I got like, choice number five.’

‘Which was what?’

She sighed. ‘Bloody Business at CIT.’

‘You put down a course in Cork?’

‘I didn’t think I’d have to worry about getting it,’ she snapped. ‘God. This is such bullshit.’

The cold cement beneath my feet was making the rest of me shiver. ‘The points must’ve gone up,’ I said.

‘Oh, you think?’

I forgave the snappiness, considering.

‘You didn’t accept it, did you, Liz? You should wait for the second round.’

‘Why?’ she said. ‘I’m not going to get it then either.’

‘You never know.’

‘Yeah, I do.’

‘So, what? You’re going to stay here for the next four years?’

‘Rub it in, why don’t you?’

‘I’m just asking what your plan is.’

‘My plan right now is to go back to sleep.’

I knew from the tone of Liz’s voice that she was in one of her moods and there was no point trying to talk her out of it. She’d decide when and where she’d get over this, and I’d just have to wait for it to happen.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Well, I’ll call you later. And I’ll see you tonight anyway.’

‘I’m not going tonight.’

I rolled my eyes. ‘Liz …’

We were supposed to be going to a party at this girl’s house, Sharon.

Her parents were away in France for a fortnight so she’d the run of the place, and the house was out in the middle of nowhere, on some back road past Ballygarvan, so there’d be no next-door neighbours to worry about disturbing. She’d invited half the class to it. A CAO Offers Day Party.

The thing was, Sharon was really Liz’s friend. They played hockey together. I didn’t know Sharon well enough to go along by myself, so Liz flaking out on tonight’s plans left me out of them as well.

‘Go back to sleep for a while,’ I said. ‘I’ll call over in a few hours. You might feel different then—’

‘I won’t.’

I was about to repeat that I was sure she’d get something at St John’s in the second round, and that to ignore this first offer, that we’d be laughing about this next week when—

Beep-beep-beep.

She’d hung up on me.

It was only when I turned to go back inside that I realised she’d never asked me how I’d got on.

——

Liz was mostly MIA for the next week. We talked on the phone a couple of times and on Sunday night I did manage to coax her out to go pick up some McDonald’s, but she was sullen and snippy for the whole hour and I was relieved when she dropped me back home.

It was only then the subject of what course I’d got came up, and the conversation was brief. She said, ‘So you got English Lit, then?’ and I said, ‘Yeah,’ and then she started talking about something else.

The following morning, two girls from our class came into the cafe where I had a summer job helping out in the mornings. We talked about where everyone was headed – one of them was going to Galway, the other had found out months ago that she’d secured a place to do something somewhere in the UK – and what we were wearing to our Debs ball, which was coming up.

‘How come you didn’t go to Sharon’s party?’ one of them asked me.

‘Oh …’ I didn’t want to say it was because of Liz, because that would be inadvertently revealing that she’d failed to get the college course she wanted and that I wouldn’t go places without her in tow. ‘Something came up at the last minute. How was it?’