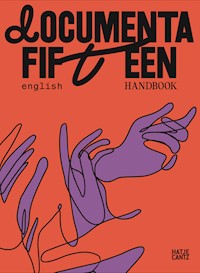

documenta fifteen Handbook E-Book

9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hatje Cantz Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Under the guiding principle of lumbung, the Indonesian collective ruangrupa is less concerned with individual works than with forms of collaborative working. As a reference work, companion, and innovative art guide, the Handbook offers orientation for these comprehensive processes; it is aimed at visitors to the Kassel exhibition as well as those interested in collective practice. All the protagonists at documenta fifteen and their work are presented by international authors who are familiar with the respective artistic practice and cultural context. Entitled "lumbung," the book introduces the mindset and cultural background of documenta fifteen illustrating the artistic work processes with numerous drawings. A chapter on Kassel presents and explains all the locations of the show, including the artists and collectives represented here.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 336

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ruangrupa and Artistic Team

A.K. Kaiza

Alvin Li

Andrew Maerkle

Ann Mbuti

Annie Jael Kwan

Ashraf Jamal

Wong Binghao

Camilo Jiménez Santofimio

Carine Zaayman

Carol Que

Chiara De Cesari

Dagara Dakin

Enos Nyamor

Farhiya Khalid

Ferdiansyah Thajib

Hera Chan

Joachim Ben Yakoub

Krzysztof Kościuczuk

Marta Fernández Campa

Max Kühlem

Nuraini Juliastuti

Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu

Pablo Larios

Ralf Schlüter

Rayya Badran

Skye Arundhati Thomas

Tina Sherwell

Jimmie Durham

I Want You to Hear These Words About Jo Ann Yellowbird

(Ars Poetica)

From what kind of yellow bird comes the name Yellowbird?

It must mean Kunh gwo, the sacred Yellowhammer.

Ka (But now), no more dreaming or explaining; Jo Ann Yellowbird took rat poison and died.

A chorus was provided a year before in

A pamphlet concerning related events:

“STOP THE GENOCIDE OF INDIAN PEOPLE” “Jo Ann Yellowbird, an activist in

the American Indian Movement, was seven months pregnant when she was kicked in the stomach

by a police officer. Two weeks later her

baby, Zintkalazi, was born dead. Jo Ann

has filed suit against the officer who kicked her

and the authorities who refused her medical treatment.”

And to show that I am a sophisticated poet and

Not a pamphleteer, I quote from the Vocabulary

Of a Lakota Primer printed to educate those children Of the Pine Ridge who have not been kicked to death:

Billy Boy said,

“I like the sheriff”

Overtake the night

Starve

Pneumonia

Wash your face

Your face is dirty

Comb your hair

Wash your clothes

Supervisor

Always take a bath

Be silent!

My eye hurts

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Earth

Plow

160 acres

Shovel

Allotment

My chest hurts

I have none

Heaven

The Pope

Church

Your ears are dirty

My ears ache

Wrong procedure

Cut your hair

Billy eya

Canakaa wustuca lake A han he ju

Aki ran

Caru na pere

Ete glu jajja

Ete nu sapa

Glak ca yo

Ha klu ja ja pi

Igmu wa pa se

Ye han nu wan po Inila yanka yo

Ista mayazan

Ta kal Tunkashile ya pi Maka

Maka iyublic

Maka i yu ta pi sope la Ma ki pap te

Makove owapi

Maku mayazan Manice

Marpiya

Oyublaye

Owacekiye

Nure ni sape

Nure opa mayazan Ogna sni

Pehin gla sla yo

from: Poems That Do Not Go Together, Wiens Verlag, Berlin and Edition Hansjörg Mayer, London, 2012

7

Mitte 228

Frankfurter Straße/Fünffensterstraße (Underpass)229ruruHaus231documenta Halle 232

Reiner-Dierichs-Platz232 WH22234 C&A Façade235KAZimKuBa235Gloria-Kino236Friedrichsplatz236Museum for Sepulchral Culture238Stadtmuseum Kassel239Fridericianum241Museum of Natural History Ottoneum 242 Hotel Hessenland242Grimmwelt Kassel245 Hessisches Landesmuseum245

Fulda 246

Hiroshima-Ufer (Karlsaue)247Compost heap (Karlsaue)249Bootsverleih Ahoi249Walter-Lübcke-Brücke249Rondell252 Greenhouse (Karlsaue)253Karlswiese (Karlsaue)255 Hafenstraße 76255

Bettenhausen 256

Hallenbad Ost257Sandershaus259 St. Kunigundis259Hübner areal260Platz der Deutschen Einheit (Underpass)260

Nordstadt 262

Nordstadtpark263Weserstraße 26264Trafohaus264

*foundationClass*collective 46 Agus Nur Amal PMTOH 48 Alice Yard 50 Amol K Patil 54Another Roadmap Africa Cluster 56 Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie 58Arts Collaboratory 60 Asia Art Archive 64 Atis Rezistans | Ghetto Biennale 66 Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture 70 Black Quantum Futurism 72 BOLOHO 74 Britto Arts Trust 76 Cao Minghao & Chen Jianjun 80 Centre d’art Waza 82 Chang En-Man 84Chimurenga 86 Cinema Caravan and Takashi Kuribayashi 88 Dan Perjovschi 90 El Warcha 92 Erick Beltrán 94 FAFSWAG 96 Fehras Publishing Practices 100 Fondation Festival sur le Niger 102 Graziela Kunsch 106 Gudskul 108 Hamja Ahsan 112 ikkibawiKrrr 114INLAND 116 Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt (INSTAR) 120 Jatiwangi art Factory 124 Jimmie Durham & A Stick in the Forest by the Side of the Road 128 Jumana Emil Abboud 130 Keleketla! Library 134 Kiri Dalena 136 Komîna Fîlm a Rojava 138 La Intermundial Holobiente 140 LE 18 142 MADEYOULOOK 144 Marwa Arsanios 146 Más Arte Más Acción 148 Nguyen Trinh Thi 152 Nhà Sàn Collective 154 Nino Bulling 156OFF-Biennale Budapest 158 ook_ 162 Party Office b2b Fadescha 164 Pınar Öğrenci 166Project Art Works 168 Richard Bell 172 Sa Sa Art Projects 174 Sada [regroup] 176Safdar Ahmed 178 Saodat Ismailova 180 Serigrafistas queer 184 Siwa plateforme – L’Economat at Redeyef 186 Sourabh Phadke 188 Subversive Film 190 Taring Padi 192The Black Archives 196 The Nest Collective 198 The Question of Funding 200Trampoline House 204 Wajukuu Art Project 208 Wakaliga Uganda 212yasmine eid-sabbagh 216 ZK/U – Center for Art and Urbanistics 218

8

10

42

44

226

266

270

274

284

8

Harvest drawings by

Indra Ameng (left) and

Studio 4oo2 (right)

9

With this handbook you will get detailed insight into documenta fifteen. While still containing general information about the exhibition, it is also informative about the important collective pro-cesses that preceded it and that permeate the show without necessarily being visible to the naked eye.

The following section, titled lumbung, is a collec-tively authored chronicle of our journey towards the 15th edition of documenta. It starts with the collective “us” of ruangrupa, the Artistic Direc-tors, and our extension, the Artistic Team, and spirals out to include more and more individuals and collectives who have joined us on the lumbung journey.

lumbung is a term you will hear a lot throughout this book and the exhibition. It refers to a concept of collective sharing that lies at the heart of documenta fifteen, and its meaning will become apparent in the coming pages. The images and drawings accompanying this section are from the lumbung harvest. The harvest is an artistic recording of discussions and majelis assemblies meant for passing forward knowledge and experi-ence. It will also be present in the different venues of the exhibition.

The handbook gives basic information about lumbung practice and the members’ and artists’ translation of their local practices to Kassel, as well as about the other artists to whom they have extended invitations. We see the three-year preparation period and associated processes as an important part of documenta fifteen. In addition, the handbook contains information about our open space, ruruHaus, and the

local ekosistem in Kassel, as well as the public program Meydan and the mediation program sobat-sobat.

This can always be only a snapshot, because documenta fifteen is not a static exhibition. Many contributions by lumbung artists and members will continue to evolve and change during the exhibition period and after.

In addition to the handbook, there are other publications dedicated to specific aspects of lumbung as practice, cosmology, experimentation, and playfulness that are, in themselves, results of lumbung processes.

We hope you will have a great time reading and spending time in the exhibition and with the lumbung members and artists. And remember! “Make friends not art!”2

ruangrupa & Artistic Team documenta fifteen

Assalamualaikum1, dear reader

1 Assalamualaikum is a com-mon greeting in Indonesia, used both formally and colloquially, meaning “peace be upon you.”

2 ruangrupa, siasat a short tac-tical guide for artist run initiative, https://www.sculpture-center.org/files/siasat.pdf

10

11

Assalamualaikum

Harvest drawings by Andrés Villalobos (left) and Daniella F Praptono (right)

12

lumbung

2019

warming up and research phase

2020

institutional and artistic building phase

2021

articulation and content finalization phase

2022

souk or istiqlal phase

2023

sustainability schemes implementation phase

system, we decided to stay on our path. We invited documenta back, asking it to be part of ourjourney. We refuse to be exploited by European, institutional agendas that are not ours to begin with. We believe that we must make this experi-ence of imagining an edition of documenta contribute back to our own endeavors.

Gudskul can be understood as a miniature of what is to come with documenta’s fifteenth edition. What ruangrupa has achieved together with Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara through Gudskul and the collective of collectives cannot be transposed literally to other contexts, not least because the investment of time and space, with its build-up of trust and friendships, cannot simply be copy-pasted. After realizing this, the timeline we first proposed was as follows:

ruangrupa is an art collective started in 2000 in Jakarta, Indonesia. Our experimentations with lumbung began critically. A vernacular agrarian term in Bahasa Indonesia, “lumbung” refers to a rice barn where a village community stores their harvests together, to be managed collec-tively, as a way to face an unpredictable future. Its initial use was as a meta-phor, to explain the possibility of putting financial resources in a central account to be managed together.

This centralized financial account and our initial approach to resources as purely financial both proved to be false. Only after several trial-and-error attempts did we realize that even shareable resources can be held by different hands, put in different pockets, and communally governed whenever different needs arise over time. Since 2013, we—ruangrupa with other Jakarta-based collectives—have tried to build ekosistems based on an understanding that even a group of people, a collective, cannot stand alone, but must purposefully play a part in their larger context—just as in nature, where different species have their specific functions and roles to keep an ecosystem in balance.

The first of these ekosistems was dubbed the Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem, taking the name of the former-warehouse complex we occupied together in Jakarta and turned into the center of many of our activities. This way-too-large experiment gave way to Gudskul Ekosistem, an informal educa-tional platform ruangrupa established with two other collectives, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara, in 2018. With Gudskul, the notion of lumbung as the operational system for the ekosistem that believes and develops as a collective of collectives carries on indefinitely. Against this background, when we were invited to make a proposal for the fifteenth edition of documenta, instead of integrating ourselves into the long-established documenta

About the lumbung processes and

how the guest becomes the host

Yet, in time, it became clear that many different forces prevented us from implementing the proto-cols laid out in the original timeline. Covid-19 was one big element, but other realities became evident, which meant we had to be ready to be tactical. Negotiation became the name of the game.

Harvest drawings by Ade Darmawan (left), and Gudskul (right)

13

About the lumbung processes and how the guest becomes the host

Harvest drawings by Ade Darmawan (left), and Gudskul (right)

14

lumbung

Harvest drawing by Daniella F Praptono

15

About the lumbung processes and how the guest becomes the host

About the lumbung processes and how the guest becomes the host

16

lumbung

After documenta accepted our invitation to join our journey and to become part of our ekosistem, we decided—with their opportunities and support—to keep on extending invitations to different people. First, to five individuals in Kassel, Amsterdam, Jerusalem, and Møn, whom we be-lieved could be an extension of ruangrupa. We thus formed the group that would become known as the Artistic Team. But there were also other initia-tives in the world which we felt were already practicing lumbung and its values. We called on them to join us in imagining together what documenta fifteen could be. The first fourteen initiatives we invited committed to becoming part of lumbung-building processes before and beyond documenta fifteen. These initiatives became known as lumbunginter-lokal members. More than 50 other artistic practices, both individual and collective in nature, joined afterwards, forming what has become known as lumbung artists.

Besides these invitations, our own existence in our current local-ities had to be carved out more deeply in Indonesia, more broadly in our international circles, and newly in Kassel. Thus, together, lumbung Indonesia, lumbung inter-lokal, and lumbung Kassel were formed, with the aim of their members identifying what resources were in their power and deciding how to use them. This way, we were sure that documenta fifteen would not be solely ruangrupa’s but would also belong to others.

This was a high-risk move, as, in the time of writing, we are still curious to see whether the 100 days of documenta fifteen will only result in pragmatic exercises—a temporary “time-off” for artists and initiatives to learn from—only to swing back to the old system of doing things, relapsing to state funding and/or free art-market systems, or even the biennial circuits. Based on our

How to do things

differently

Harvest drawings by Abdul Dube (left) and Nino Bulling (right)

17

How to do things differently

systems, or even the biennial circuits. Based on our different past, collective experiences of operating within these existing systems, they have proven to be highly competitive, globally expansive, greedy, and capitalistic—in short, exploitative and ex-tractive.

Will the much-needed dissolution of ownership and authorship happen in documenta fifteen? How will economy, credits, and aesthetics be practiced and therefore understood differently in the 100 days? These are things that we’d like to see happen.

There are different ways and practices of producing art (works). These practices are not (yet) visible, as they do not fit the existing model of the global art world(s). documenta fifteen is an attempt to clash these different realities against each other, showing that different ways are possible. Instead of fitting these various modes of production into what exists already, it should act

as a series of exercises for reshaping and sow seeds for more changes in the future. Different ways of producing art will create different works, which, in turn, will ask for other ways of being read and understood: artworks that are functioning in real lives in their respective contexts, no longer pursu-ing mere individual expression, no longer needing to be exhibited as standalone objects or sold to individual collectors and hegemonic state-funded museums. Other ways are possible. In this way, we are resisting the domestication or taming of these different practices.

Harvest drawings by Abdul Dube (left) and Nino Bulling (right)

18

lumbung

Harvest drawings by

Nino Bulling (left)

and Abdul Dube (right)

19

Approach to Kassel

From the off, we have experienced Kassel as an urban organism and ekosistem of local initiatives and collectives, rather than as exhibition context and history. To open a dialogue with surrounding ekosistems, we identified a number of interlinked “acupuncture points,” using the analogy of the ancient Asian medical practice of healing the body with a slow but holistic method that looks at the workings of the body system and its millions of nerves and arteries. This logic of acupoints in a network of energy paths was used to approach the venues and spaces of documenta fifteen. Infiltrating the urban fabric of Kassel, decentraliz-ing the center, and opening connections to the less culturally used areas in the East.

In Jakarta, out of necessity, ruangrupa would rent domestic houses and turn them into exhibition spaces, especially for art students to hang out, program, exhibit, and even live in. So, a bedroom and a living room could become exhibition spaces that would simultane-ously be someone’s living quarters. In keeping with this approach, we started ruruHaus in the center of Kassel as a shared living room in the city. While “ruru” is short for ruangrupa, the idea of ruruHaus is not for ruangrupa to occupy space in the city center, but to be part of a context where ini-tiatives from Kassel (and visiting artists and members) can con-nect, and where they can extend themselves into the future as a collective of collectives.

In Europe, there tend to be very centrist ideas about knowledge, history, and art, ideas that we would like to decentralize or decompress within the ruruHaus. In the summer of 2020, amid the pandemic, two members of ruangrupa moved to Kassel when the first window since lockdown be-gan made international travel possible again. Their focus became hosting the Kassel community along with all the visiting members and artists for whom ruruHaus would not be just a living room, but also a laboratory to test their planned translations from their own locales to Kassel’s ekosistem.

Other than the 65-year tradition of docu-menta, we encountered many other local initiatives in the city, making it possible for lumbung to take on even more meanings in Kassel. We began looking at the initiatives to understand how (self) sufficient they were and if they had a surplus that they would like to share. This could be anything: from something educational to diverse experiences.

Approach to Kassel: ruruHaus

and the fact that “We could

sleep in the living room”

20

* We later regretted this division of 20,000 Euro per artist, or communicat-ing it this way to the artists. At times it created a sense of individual ownership of each 20,000 Euro in the common pot. If we had communicated the total sum, the conversations might have differed. In some mini-majelises, the conversations led to a consideration of the total sum of the budget, while in others the artists who were more present and active in the majelises felt like they could not govern the budgets of the absent artists, and so offered them back to the artists.

lumbung

Harvest drawings by

Dan Perjovschi (left) and

Jazael Olguín Zapata (right)

21

While our collective experiences under

Covid-19 relegated us to the disem-

bodied space of video conferenc-

ing, they allowed us to reflect

again on the value of solidarity.

We needed to go even further

in fostering new networking

models and more sustainable

structures for small-to-medi-

um arts initiatives. Consequently,

we needed to rethink still further

what artistic practices and events are,

what they could and should be. All these

issues relate to socio-political problems faced

in the members’ respective contexts, from Jakarta

and Chocó in Colombia to Jerusalem; Nairobi,

Kenya; Havana, Cuba; Dhaka, Bangladesh; and

many other cities and villages where lumbung members practice.

Following ruangrupa’s longstanding practice of dividing money and resources accord-ing to needs (a duo has different needs to a large collective, the needs of a person living alone and a parent with a big household are not the same), we considered our options, one of them being paying basic income to everyone for the entire time of working with documenta fifteen. Having looked into the figures, we faced the fact that, if we paid everyone a basic income, we wouldn’t have sufficient budget for even a medium-sized exhibition. One solution, which we dubbed “full lumbung,” was to stick to the 25 lumbung mem-bers that ruangrupa proposed in their original invitation to documenta and ask them to involve more of their ekosistem in their translation of their local practice to the exhibition in Kassel. The stakes were high, given that many commen-tators in Germany and beyond took ruangrupa’s appointment and the lumbung concept to mean there being no exhibition at all, or an exhibition of non-art, in 2022. Furthermore, we were having Zoom visits with many artists who were

working in and out of collectivity in

their locales, and whom we felt

would enrich the lumbung

process and the exhibition.

So, we had to come up

with a model that would be

fair, even if not ideal, that we called gado-gado (a dish with

a bit of everything from the

Indonesian kitchen).

In the end, we decided to stick to

the fourteen members we had already

invited for the long haul and invite about

50 artists, mostly collectives, to commit to the

lumbung process and the 100 days in Kassel. The production budget for each lumbung inter-lokal member is 180,000 Euro, and 25,000 Euro seed money. Seed money is a budget paid upfront, which we see as an acknowledgment of the years of work in the artists’ localities and as a seal of our agreement to find translations of that work to Kassel in 2022. This translation in its turn is made in such a way that it becomes (re)generative for the work beyond documenta fifteen. For many, the budget came at a crucial time, strengthening their sustainability during the pandemic. While the artists received the equal amounts of 60,000 Euro for production, with 10,000 Euro seed money for collectives, and 5,000 Euro for individuals. This came out of a long discussion among the Artistic Team members and the documenta gGmbH. The discussion started with the aim to distribute part of the available budget to all the involved artists as basic income, or for basic needs. However, as the discussion ensued the idea of a common pot occurred, with 20,000 EUR per participating group in collective management, in order to leave it to the artists themselves to decide how to use it in the exhibition.*

“You are Mute”

(Covid-19 reality hitting) and going from full lumbung to gado gado

“You Are Mute”

23

From Mini To Akbar

Harvest drawings by

Tropical Tap Water

24

Through majelises, the lumbung artists and lum-bung members could become part of the collective curatorial process and the wider documenta econ-omy, or documenta lumbung. Before the pandemic, our idea was for majelises to occur every 100 days in order to decide collectively on the building of the exhibition, the principles of how to distribute resources, and other matters. The majelis is a learning space, where there is no competition. The majelises were to be held in a different city every time, and to be hosted by lumbung mem-bers. However, as a result of the pandemic, it was necessary to hold the majelises online.

The fourteen lumbung inter-lokal mem-bers have been discussing how to build both the exhibition and the longer term lumbung econ-omy—beyond documenta fifteen—since June 2020, at first in bi-weekly majelises with the entire lumbung inter-lokal, and later in smaller groups. These discussions have produced several working groups that have taken on topics that are of common necessity. Most collectives in the lumbung inter-lokal come from contexts where the state had failed to support the development of infrastructure and a support system for art and culture.

Since the model of the stable institution had failed, they had seized the opportunity to rethink institutions. So, the questions of economic survival and autonomy were central in the lumbung inter-lokal. An economy working group grew out of discussions around what sustainability is and various experiments with currencies and circular economy, inviting econo-mists to work sessions and putting forward ideas and mechanisms. Out of this working group, new ones formed: lumbung Gallery,lumbung Kios, and lumbung Currency working groups were set up to experiment practically with various ways to sustain and ask cultural questions through economic projects, as well as sustaining the lumbung pot after documenta fifteen. Another pressing issue in the lumbung inter-lokal mem-

bers’ localities is land, since, whether endangered by corporate, political, or urban infringement, the sustainability of the members’ ekosistems is at stake in the long run. The important discourse around the lumbung members’ artistic practices led to another dynamic discussion and what we called the “Where is the Art?” working group. lumbung.space and a lumbung of Independent Publishers grew out of the need to amplify those discourses, where art and life are one.

lumbung

From mini to akbar:“We are not in documenta fifteen, we are in lumbung one”

25

From Mini To Akbar

Harvest drawing by Indra Ameng

26

lumbung

Harvest drawings by

Sari Dennise (left) and

Andrés Villalobos (right)

27

With all the different majelises established—ten in total—we needed a gathering space for the majelises to come together and to get an overview of all the discussions going on. Our answer was to host a mega assembly, known as majelis akbar, on a regular basis. These online meetings have been attended by 150 to 200 artists and members. In these meetings, members and artists talk about specific projects for artists and members to collaborate on, as well as on how to be in solidarity with each other, and how to share space, knowledge, program, and equipment together during the 100 days. Examples of this are: Cinema Caravan opening their cinema for others to use, the ZK/U turning their building’s roof into a boat and bringing it to Kassel for other artists in the lumbung to activate, Party Office opening up the public program they host in their venue in WH22 for other artists to organize, and Richard Bell opening his Tent Embassy for artists to converse in during the hundred days and many more.

The majelis akbar was also a place for discussions about issues in the local context of lumbung members, for exchanging ideas about col-laboration, and for forging solidarity. For example, we also talked about how we should respond to accusations of anti-Semitism that emerged from a Kassel blog in January 2022 and were picked up by German media. documenta fifteen, the artistic direction, team members, and individual artists were attacked in a way that we understood as racist. This was a shock to us and even led to concerns for our safety. During majelis akbar in January 2022, the artists discussed how both the lumbung and documenta could stand behind and, in the spirit of lumbung, support those affected. documenta also published several statements in which it rejected the accusations and made it clear that anti-Semitism and racism have no place at documenta fifteen. At the same time, it emphasized the right to freedom of expression in art, culture, and science. The majelises have been important tools to develop common understandings and

solidarity with everyone’s local contexts, allowing us to learn from differing situations and conditions in each of the lumbung localities, especially where there has been political upheaval over the two years leading up to documenta fifteen, such as in Colombia, Palestine, Cuba, and Mali. This has also compelled us to develop a common discourse on our artistic practice.

The Where is the Art? working group grew out of this strong, shared necessity among lumbung members and artists to discuss how art is rooted in life and their social, activist, economic practices, and not limited to disci-plines or definitions. Every inter-lokal member experiences a distortion in the way their practices are translated to the mainstream international art scene, and what it tends to define as “art.” We established a working group that organizes workshops in local ekosistems and among artists and members, which formed the basis of building a collective language and knowledge base across practices and contexts.

The lumbung land working group, on the other hand, has been discussing developing a way of “investing” by using the collective pot in specific land projects run by members—projects that question ownership of land, that start from community needs and collective use and gover-nance, and that combine agriculture, biodiversity, culture, and the spiritual. Combining experimen-tation on land with experimentation on currencies and decentralized autonomous organizations would be a start towards building a true, interlocally connected and collectively governed economy.

While the conversations in the economy working group about how to sustain ourselves beyond documenta fifteen were ongoing, we learned from the permanent staff that has pro-duced previous editions that most of the artworks exhibited are sold backstage by gallerists during the hundred days of the exhibition and shipped to the collectors afterwards. We decided to move this to the front stage to make questions about

From Mini To Akbar

28

economy, ownership, labor, and exchange a matter of culture while at the same time attempting to secure resources for the lumbung members. As a visitor to the exhibition, you will come across the lumbung Kios; a network of decentralized and self-run kiosks trading goods made by the artists. In the lumbung Kios and Gallery, most of the returns will be stored into a collective pot, which is shared with all lumbung artists and members through a majelis mechanism.

Since the members and artists of the lumbung need to be constantly in touch with each other and the wider ekosistems, we needed digital platforms which are not conditioned by liberal market economy and institutional politics. lumbung.space, but also lumbung Press are mediums for lumbung artists and members to communicate with each other and the larger public. While lumbung.

space is an experimental social and publishing platform for sharing harvests by all the members online, the lumbung Press is a physical space and tool to realize artistic printing projects. lumbung.space is non-extractive, co-governed by the users, and is built on open platforms. It functions as a lumbung with a members-only backend for artists to store, discuss, and orga-nize content and a frontend where users can see and interact with the published content. Centrally stationed in documenta Halle and active from well before the opening and throughout the 100 days of documenta fifteen, lum-bung Press is a proper offset printing workshop where artists can be closely involved in the printing process of their own publi-cations, host events, and acquire skills needed to operate the printing press for the long haul, should the lumbung have the needs and means to keep it running after the exhibition.

lumbung

29

From Mini To Akbar

Harvest drawings by

Andrés Villalobos (left)

and Safdar Ahmed (right)

30

documenta fifteen is practice and not theme based. It is not about lumbung, or the commons, or any such notion. When we started, we realized that making a “showcase” of collective practices, done by many already in many art centers, would be a trap. Instead, this exhibition and journey are with collectives and artists who have longstanding experience with practicing and not preaching (much)—walking the talk—and who would like to learn new tricks, strategies, and approaches from one another to enrich their local communi-ties. So, in a way it is a study of many models.

How do people create the material and im-material infrastructures they need to nurture and sustain themselves and their ekosistem? Artists, collectives, and artist-led-institutions joined the lumbung based on how they practice. This was sometimes not immediately visible in their artistic work, but rather in the artists’ and collectives’ larger roles forming or participating in social and political movements. We are more interested in how the artists are working in their respective localities, and their practiced values.

Art is rooted in life. The ensuing objects and methods help in thinking through the issues at

hand and in finding solutions that are useful to the community. In this way it is impossible to separate art and life, and it is meaningless to exhibit the objects in Kassel without finding translations of the processes that give rise to them. So, instead of following the logic of commissioning new or exhibiting existing work, we asked all lumbung members and artists to keep doing what they are doing while harvesting it and to think about how to translate their practices to Kassel. Making one’s resources shareable within the lumbung is already a translation in itself. To make documenta fifteen the least extractive it can be, we continue to question how the artists’ “contributions” to documenta fifteen can also cycle back to each of the artists’ local context and ekosistems, and how meaningful it is.

lumbung

“Keep on doing

what you’re doing …”

Harvest drawings by Cem A. (left) and krishan rajapakshe / *fC*c (right)

31

“Keep on doing what you’re doing…”

… and find a translation

to Kassel

Translation should not be understood too literally, but more as a poetic way of bringing something already existing in touch with more potential users. In contrast to commissioning, which would mean bringing more stuff into the world, translation thus became a way for the artists and collectives to continue practicing in their localities, without having to put their often longstanding work on hold in order to be part of a big art event such as documenta. Some have har-vested assemblies in their localities and brought them to Kassel as models and challenges to learn from and in conversation with others. Many have moved their practice to Kassel as temporary occupations of the city. Others have extended their invitation and budgets to colleagues from their ekosistems to work alongside them in Kassel. Connecting their localities on the one hand and Kassel on the other, all artists have redistributed resources in a circular flow of money and cultural capital between the two sites.

When we started hanging out in conversa-tion with the artists it was shortly after Covid-19 was declared a pandemic. We thought we had two years to build and fill the lumbung with resources for both the everyday and crises alike. With Covid, the collapse came much earlier and with such brute force that it pressured us to consider how we could speed up and start sharing resources straight away. At the same time, we insisted on going slow, meeting several times, and building up trust. We wanted to get to know everyone better and to let them experience us and our dynamics, beyond simply discussing their artworks.

Speaking to the artists about how they coped with Covid in their local communities helped us understand more about their survival strategies and to decouple from their actual artworks. In this manner, we have developed a way of working collectively where we present practices or projects and the people behind them to each other, and then discuss them in several steps that allow for time to revisit and reflect. Our different processes follow different paces and

modes, but common to them all are trust, intuition, collectivity, and accepting that we might be wrong and make mistakes.

In the beginning, we spoke a lot about find-ing mechanisms for practicing lumbung values at an expanded scale. Mechanisms that can be shared without becoming mechanistic, or disciplines that one would need to follow to be lumbung. Just as lumbung is not a theme, neither is it a discipline. Intuitively, every time we invent a principle, we don’t see it through completely; we happen to leave a part open and unruly, like when we decided to turn Fridericianum into a school but still needed the space for work that demands controlled muse-um conditions. Our approach is nonsystematic, not crystalline or exhaustive. It is dynamic, and changes according to conversations between people and their needs, rather than based on one static line of conceptual thinking.

Harvest drawings by Cem A. (left) and krishan rajapakshe / *fC*c (right)

32

lumbung

In thinking about translation to Kassel, we grouped the lumbung artists in what we termed mini-majelis, small assemblies of four to five artists (individuals and collectives), put together according to time zones, due to digital meetings, and to existing friendships predating Covid that could nurture trust-building online. The first mini-majelises started meeting in February 2021. Artistic Team met with the groups a few times, but then left it to the artists and a curatorial assistant to decide on the rhythm and way of meeting, and, crucially, on how to make decisions around their common resources, known as the common pot. As one of the artists pointed out, the common pot is like a totem pole, something highly symbolic that holds the community together. On one hand the artists have been generous with their time and knowledge with each other, and on the other it was a challenge for them to decide on the common pot together because they didn’t know each other so well. It was also a challenge that the budget had to be spent by September 2022 and that all budgets pertaining to documenta are conditioned by traditional exhibition logics, with the bulk of spending being allocated to the narrow time frame of a limited exhibition period and not the extended spacetime of lumbung building.

The mini-majelises adopted different ways of running the majelis and making decisions. One group used agraw; an assembly from the North African Amazigh tradition, which takes the phys-ical form of a circle where the moderator walks around the circle, while participants stop the mod-erator if they wish to speak. A Zoom version of this was adapted in the majelis. Another mini-majelis met over dinner on Zoom and spoke in depth about their recipes and food as well as their practices. Another group would always decide on two hosts each time, who would prepare the session together and ask questions of everyone, passing the mike around, as well as taking turns to present their art practices for each other.

These meetings happened over the course of almost a year and a half for some groups online. Some of the mini-majelises met in Kassel, as we tried to organize their trips to coincide with each other. In early 2022, we asked them for their final decisions on their common pot budgets. Some of the artists redirected the budgets back into their

production budgets, mostly to be able to host more collabo-rators from their ekosistem in Kassel, or to support them in their localities after discussing with the rest of the members of their mini-majelises. Many of the artists decided to invite artists to present work in the exhibition, such as Nino Bulling, Jumana Emil Abboud, Safdar Ahmed, Alice Yard, Kiri Dalena, and Saodat Ismailova. Many worked on common projects, such as the mini-majelis that BOLOHO is part of, as they developed an online shop for which the whole mini-majelis is making artworks and developing artistic advertisements. Another majelis made a public program together called “chasing the sunset” to be held during the 100 days to allow lumbung members and artists to get together. Some members and artists have managed to use funds from the common pot to visit each other before the opening, such as Jatiwangi art Factory visiting Más Arte Más Acción in Colombia.

Many majelises are still trying to use the common pot for meeting and exchang-ing after the passing of the 100 days of documenta, and are trying to find ways to do so, despite the conditions of the funds. Fridskul is somewhat of a different mini-majelis, as the group also share the Fridericianum. Through their ma-jelises they have come to see it as a neighborhood, where in addition to their project spaces, they share living spaces, a library, as well as a public program.

Harvest drawing by Angga Cipta

33

… and find a translation to Kassel

Harvest drawing by Angga Cipta

34

lumbung

Since artists were neither responding to a theme nor to venues in the city of Kassel—unless through collaboration with collectives and artists in our Kassel ekosistem or because they find it regenerative for their own locale and ekosistem—we had to approach the distribution of venues differently. Function became an important aspect in locating a venue for a project. The spaces were matched with artists according to the functional needs and use of the spaces. For example, one difficulty was finding affordable accommodation for the collectives who have to inhabit Kassel for longer periods. Parts of venues were converted into living space, apartments, and dormitories by the artists. This is also connected to many of the artists’ practices in their localities that combine living and working space, private and public, art and life. Many artist collectives who were inhabiting the same venues also started to form majelises to discuss how to share the building together.

The process of the distribu-tion of the venues was dynamic. Apart from using the functional distribution of artists to venues, another proactive approach was for artists to find venues which fit within their practices. In some cases, the needs and uses of different collectives overlapped in the same venues. Another way of organizing the artists in the venues grew organically; especially with lumbung inter-lokal members, who had more time to develop collaborations. Artists started to choose spaces that were spatially