Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ryland Peters & Small

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

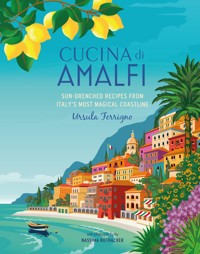

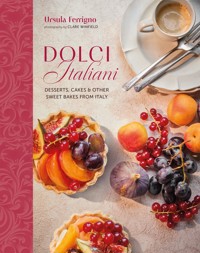

Over 70 irresistible RECIPES for ITALIAN DESSERTS, cakes, tarts, pastries, gelato and more! CREAMY and INDULGENT, to LIGHT and REFRESHING, the authentic Italian recipes in this book CATER TO ALL TASTES. BESTSELLING author URSULA FERRIGNO imparts her knowledge of the sweet side of Italian cuisine through her passion for Italian food. Picture the scene – you're sitting in a delightful trattoria on the Amalfi coast on a warm summer's evening after a day by the sea, enjoying a small slice of the melt-in-the-mouth torta that the waitress recommended. You walk back through the cobbled streets back to your hotel and spot a gelataria and can't walk past without enjoying a scoop of the most delicious pistachio gelato you've ever experienced. Dolci Italiano holds the secret to bringing that feeling into your own kitchen with this unmissable collection of the best Italian desserts. Recipes range from classics such as Lemon & Pistachio Torta, Cannoli (small filled pastry shells), and Sweet Ricotta Bread, to the more adventurous Bomboloni (small doughnuts), Pizza Dolce and Zabaglione Ice Cream. From ending the meal at a large family gathering, to a special bake for a festival or celebration or making some small treats to take when visiting friends, there's a dessert for every occasion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DOLCI Italiani

DOLCI Italiani

DESSERTS, CAKES & OTHER SWEET BAKES FROM ITALY

Ursula Ferrigno

photography by CLARE WINFIELD

DEDICATION

To Mummy and Daddy in their memory.

Senior Designer Toni Kay

Senior Editor Abi Waters

Head of Production Patricia Harrington

Creative Director Leslie Harrington

Editorial Director Julia Charles

Food Stylist Kathy Kordalis

Prop Stylist Zoe Harrington

Indexer Vanessa Bird

First published in 2025 by Ryland Peters & Small

20–21 Jockey’s Fields, London

WC1R 4BW

and

1452 Davis Bugg Road Warrenton, NC 27589

www.rylandpeters.com

email: [email protected]

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text © Ursula Ferrigno 2025

Design and commissioned photography

© Ryland Peters & Small 2025

Printed in China.

The author’s moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-78879-682-8

E-ISBN: 978-1-78879-704-7

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

US Library of Congress cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland www.arccompliance.com

NOTES

• All spoon measurements are level unless otherwise specified.

• All eggs are medium (UK) or large (US), unless specified as large, in which case US extra-large should be used. Uncooked or partially cooked eggs should not be served to the very old, frail, young children, pregnant women or those with compromised immune systems.

• When a recipe calls for cling film/ plastic wrap, you can substitute for beeswax wraps, silicone stretch lids or compostable baking paper for greater sustainability.

• When a recipe calls for the grated zest of citrus fruit, buy unwaxed fruit and wash well before using.

• Ovens should be preheated to the specified temperatures.

CONTENTS

Introduction

CAKESTorte

TARTS & SWEET BREADSCrostate e pani dolci

SMALL CAKES, PASTRIES & BISCUITSPasticcini e biscotti

DESSERTSDolci

ICE CREAM & SORBETSGelati, semifreddi e sorbetti

EDIBLE GIFTSRegali

Index

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

The Italians, as a nation, have a very sweet tooth, and sweet things are very much part of daily life. This passion is said to have been inspired by the seafaring and trading Venetians, who were among the first in Europe to refine and trade in sugar. Up until about the 12th century, honey and fruit were the only sweeteners in the West (plus maple syrup in North America). It is not clear who first discovered the properties of sugar cane, but the Arabs certainly knew how to refine it, and this ensuing ‘white gold’ was introduced to Europe, via soldiers returning from the 11th-century Crusades. The Venetians then developed sugar-refining factories in Tyre, in modern-day Lebanon, before moving them to the island of Cyprus, a Venetian possession for a time.

The Venetian Republic had a monopoly on sugar (and on spices, coffee and chocolate) until the discovery of America. On his second voyage in 1493, Christopher Columbus planted sugar canes on islands in the Caribbean. There the canes thrived, liking the climate much more than that of Europe, and so the Venetian monopoly was broken. By the 18th century, the West Indian islands were the main world source of sugar, and its production, sadly, contributed massively to the abhorrent slave trade.

The Arabs were also important in other sweet aspects of Italian cuisine. They ruled Sicily for roughly 200 years. Apart from sugar, they introduced many trees, fruits and nuts – chiefly pistachios, figs and citrus fruit – and these are hugely important in many Italian cakes, pastries, biscuits/cookies and puddings. They were also responsible for the ice creams for which Italy is now so renowned. The story goes that they flavoured snow from Mount Etna with fruit juices and syrups, thus inventing gelati and sorbetti. My recipes in the relevant chapter are a little more sophisticated…

So a liking for sweet flavours has long existed in the Italian palate. And that, married with the Italians’ love of celebrating, means that sweet things – cakes, pastries, biscuits – are intuitively associated with occasions such as birthdays, christenings, weddings, saints’ days and religious festivals such as Christmas and Easter. But it actually goes further than that: the Italians love sweet things so much that they indulge almost on a daily basis – a quick small pastry with a coffee for breakfast, or a slice of something delicious mid-morning or -afternoon. After the riposo (the Italian siesta) is a popular time for having something sweet: this gives a burst of energy for the rest of the day (so they say!). Visiting friends and family conjures up yet another excuse: I wouldn’t dream of popping in to see neighbours or friends without taking with me a box or bag of homemade biscuits.

And of course the displays in Italian pasticcerie are always so enticing, it is difficult to pass without staring and indulging! In October last year, when I finished teaching in Puglia, some students and I shared some pasticciotti (a speciality of the region, see page 103) in a tiny bakery in Specchia: a coffee, pastry and glass of iced water, all served with such pride. I am proud of all the following recipes and hope that some, or many, of them will inspire you.

A FEW NOTES ON INGREDIENTS

To make Italian cakes, pastries, biscuits/cookies and puddings, all you need are good ingredients, and I cannot emphasize this enough. The eggs must be fresh, because the fresher they are, the more air they will trap when beaten, particularly important in sponge-making. Fresh eggs also add colour and inimitable flavour, and I try to find Italian eggs, but you can use free-range or organic. When I use Italian eggs, my pasta is richer and yellower, as are my custards.

The sugar must be caster or superfine; as it is finer than granulated, it blends in more easily. The flour for cakes, sponges and pastries should be plain/ all-purpose, soft and sifted (this traps the all-important air): Italian 00 flour is perfect, because it has already been sifted twice (thus the two 0s). I don’t, however, use self-raising/rising flour very often, as I think a combination of 00 and baking powder is much more potent. Other flours can also be used, such as buckwheat or chestnut flour, or fine polenta/cornmeal. And please, always, seal a flour packet tightly; it goes stale if exposed to air, which can affect baking results, and can pick up migrating flavours.

Try to buy nuts in the shell, and crack open when needed. They will be much fresher. Fruit should be as fresh as possible, and in good condition. One fruit that I use a lot is the lemon. You can buy unwaxed lemons, but if you are unsure, simply scrub the lemon skin with a clean, soap-free brush under cool running water. Dry before use.

A FEW NOTES ON EQUIPMENT

For most of the recipes in this book, you need an oven, and this should be reliable. If your oven is performing a few degrees of heat up or down from the displayed temperature, this is enough to potentially ruin a cake. To test how efficiently your oven is working, buy an oven thermometer and hang it from the middle rack of the oven. Turn the oven on to about 200°C/Fan 180°C/400°F/Gas 6. Keep the oven door closed until the oven alerts you that it has reached the set temperature. Check the oven thermometer. If the temperatures match, you are fine. If not, perhaps you should get an engineer to have a look.

Other factors come into play when baking in your oven. You must always preheat it before cooking, about 15 minutes usually, and position the shelves carefully. A cake should be in the centre of the oven. And when baking more than one cake at a time, stagger them rather than having them directly above or below each other. Even though your oven might be working well, it is always a good idea, halfway through baking, to turn a cake pan, baking sheet or muffin tray around. But never open the oven door until the item you are cooking has set and is lightly browned or it may sink.

Considering oven pans, you should always use a cake pan the same size as I have specified, otherwise the recipe might not work so well. Similarly, springform pans are better in some circumstances than loose-bottomed. I use middle-weight metal pans, many of them non-stick, which makes cake removal much easier. I use baking paper (also known as greaseproof/ wax paper) to line baking sheets and cake pans. I give instructions on how to line cake pans below, but various shapes and forms are available ready-made, as paper liners or silicone moulds, ready-to-use, from good kitchen shops.

LINING ROUND CAKE PANS

1Place a sheet of baking paper on your work surface. Cut a strip about 5 cm/2 inches taller than the height of the pan, making sure it is long enough to wrap around the inside of the pan.

2Fold over one long edge of strip by roughly 3 cm/ 1¼ inches. Make a series of small cuts along this folded edge.

3Take another sheet of baking paper and draw a circle around base of the pan. Cut out the circle.

4Lightly grease the bottom and sides of the pan with butter. Press the strip around the sides of the pan with the cut edge folded into the centre of the base. Lay the paper circle in the bottom of the pan over the cut edge.

LINING LOAF & SQUARE PANS

1Grease your pan, then place it on top of a sheet of baking paper. This must be big enough to come up the sides of the pan. Make a pencil mark at each corner of the tin, then cut the paper from the outside diagonally towards the mark at each of the four corners.

2Carefully place the baking paper inside the pan, and the cut edges will overlap, lining the pan snugly. Cut off any excess paper.

CAKES

Torte

Cakes for every occasion

Italian cakes are luscious and full of flavour, and are made mainly in special pastry shops – pasticcerie – rather than in restaurants or at home. Sadly, away from Italy, we don’t have easy access to authentic pasticcerie, so I am here providing you with recipes for a wonderful array of Italian cakes to make in your own kitchen. They are as delicious as anything shop-bought, probably more so (if I say so myself), and are easy to make.

Most Italian families buy cakes for special occasions such as Easter, Christmas, other Christian celebratory days and for birthdays. But they also eat cake on a day-to-day basis (the Italians really like cake!): with coffee in the morning, for merenda (snack) at tea time, or after a meal. I have seen people in cafés having a glass of something alcoholic and a slice of cake for breakfast. I think I draw the line at that…

But one cake is often made at home, and that is the Italian sponge, pan di Spagna (so-called because it was introduced to Italy by the Spanish invaders of Sicily). Classically it is a mix of egg yolks and caster/superfine sugar, into which beaten egg whites and flour are gradually folded. The French savoie biscuits (the sponge fingers used in tiramisù) and cake are similar. But an Italian sponge cake can also be made using whole eggs, which is similar to the French genoise – the name coming obviously from ‘Genoese’, suggesting an Italian influence. I wonder which came first? Sometimes butter can be included, which makes the cake denser and slightly longer-lasting. Light, soft and airy, the Genoese sponge cake on page 47 can be eaten filled or topped, and is used as the basis of many Italian puddings such as zuppa Inglese (see page 129), cassata (see page 122) or zuccotto (see page 126).

Chocolate is a favourite cake flavouring in Italy, as is coffee. Spices make their appearance too, as do many nuts, such as walnuts and hazelnuts. Almonds are even more common, as they grow prolifically in the south, introduced by the Arabs when they ruled Sicily. The Arabs also imported pistachios from the Middle East, and these are used a lot in Italian cake-, biscuit- and gelato-making. I have a real soft spot for pistachios. I love eating them dried and salted, splitting the shells open with my fingernails; they are wonderful cracked and glued decoratively to the sides and top of a creamy cake, and in the ricotta filling of Sicilian cannoli (deep-fried pastry tubes, see page 96).

There is a great Italian tradition of preserving fruit, and these products find their way into many an Italian cake. Some are dried – grapes as raisins, plums as prunes, apricots as themselves! – and eaten as they are, as a wholesome snack or included in cakes and other foods. Some fruits are candied (see page 170), usually the peel of oranges, lemons, grapefruit and citrons. Candied citrus peel is used in the Milanese panettone, in a filling for Sicilian cannoli, and in cassata. Candied pumpkin is often used in the classic Tuscan panforte, and chestnuts are candied for the luxurious Italian version of the French marrons glacés, marroni canditi. (An unusual variation on the theme is mostarda di Cremona, where candied fruits is cooked in a mustard syrup and served as an accompaniment to boiled meats or cheese.) But fresh fruits are used too, such as apples, apricots, raspberries and pears, and citrus juices are a common flavouring in cakes from southern Italy. Even vegetables are used: I have given you an unusual Italian carrot cake here!

CHERRY & RICOTTA CAKE

Torta ricotta e ciliegie

Ricotta gives a gloriously squidgy texture to this cake, which is to be enjoyed in the cherry season. We are exposed to many different varietals in Italy, but on a recent trip, we used plums (the same quantity), quartered, in place of cherries to great effect.

150 g/⅔ cup/1¼ sticks unsalted butter, softened

225 g/1 cup plus 2 tablespoons caster/superfine sugar

250 g/generous 1 cup ricotta

2 lemons, grated zest of both and juice of 1

4 large/US extra-large eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 tablespoons cherry vermouth

175 g/1⅓ cups self-raising/ rising flour

½ teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon fine sea salt

50 g/½ cup flaked almonds

200 g/1 cup stoned/pitted cherries

icing/confectioners’ sugar, for dusting

20-cm/8-inch springform cake pan, greased and lined

Serves 8–10

Preheat the oven to 180°C/160°C fan/350°F/Gas 4.

In a stand mixer, beat the butter and sugar until pale and creamy. Beat in the ricotta and lemon zest until combined. Add the eggs, one at a time, making sure each one is incorporated before adding the next. Beat in the lemon juice, vanilla and cherry vermouth.

Combine the flour, baking powder and salt in a sieve, then sift over the butter mixture and fold together. Fold in half of the almonds until just incorporated, making sure not to over-mix. Scrape the batter into the prepared pan and scatter the cherries on top, followed by the remaining almonds.

Bake in the preheated oven for 50–60 minutes until a skewer inserted comes out clean. Cover with foil towards the end of the cooking time if the cake is browning too much.

Remove from the oven and leave to cool completely in the pan. Release from the pan and lightly dust with icing sugar to serve.

HAZELNUT & CARROT CAKE

Torta di carote e nocciole

This is a winning combination created by my friend Madalena in Selci Lama, a small village near Perugia. If I didn’t include this recipe I would be extremely disappointed in myself. She owns a bakery, hence the inclusion of cake crumbs. Most carrot cakes have a cream cheese topping, but the Italian version is just as it is and I find that equally as delicious. A lighter and healthier version.

340 g/12 oz. organic carrots, peeled and finely grated

170 g/1⅓ cups hazelnuts, toasted and ground

60 g/2 oz. cake crumbs (Madeira or sponge cake)

1 teaspoon baking powder

2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

grated zest of 1 lemon

5 large/US extra-large eggs, separated

110 g/½ cup plus 2 teaspoons caster/ superfine sugar

icing/confectioners’ sugar, for dusting (optional)

23-cm/9-inch cake pan, greased and lined

Serves 6–8

Preheat the oven to 160°C/140°C fan/325°F/Gas 3.

Place the carrots in a bowl with the hazelnuts, cake crumbs, baking powder, cinnamon and lemon zest.

Beat the egg yolks with half the sugar using a stand mixer until thick enough that the whisk will leave a trail. Fold it into the carrot mixture.

Whisk the egg whites until stiff, but not too dry. Whisk in the remaining sugar. Carefully fold the meringue into the carrot mixture using a large metal spoon.

Spoon the cake batter into the prepared pan and bake for 1¼ hours until golden and well risen.

Serve with a dusting of icing sugar if desired.

CHESTNUT, CHOCOLATE & HAZELNUT CAKE

Torta di castagne, cioccolato e nocciole

This is perfect as an alternative to Christmas cake. It has a celebratory feel with the inclusion of orange, chestnut and brandy. It can also be made dairy free very successfully by using plant-based alternatives.

250 g/2 cups cooked chestnuts

150 ml/⅔ cup full-fat/whole milk

75 g/2¾ oz. dark/bittersweet chocolate (70% cocoa solids), roughly chopped

50 g/⅓ cup hazelnuts, toasted and chopped

60 g/¼ cup/½ stick unsalted butter, softened

125 g/⅔ cup caster/superfine sugar

3 large/US extra-large eggs, separated

1 tablespoon brandy

grated zest of ½ orange

100 g/3½ oz. sweetened chestnut spread

100 g/½ cup crème fraîche

icing/confectioners’ sugar, for dusting (optional)

18-cm/7-inch cake pan, greased and lined

Serves 6–8

Preheat the oven to 180°C/160°C fan/350°F/Gas 4.

Soak the chestnuts in the milk for 10–15 minutes until soft, then drain and discard the milk.

Whizz the chocolate in a food processor until it forms a coarse paste, then set aside. Rinse out the processor, then add the chestnuts and hazelnuts and blend to a rough paste. Set aside.

Put the butter and sugar in the processor and cream together until smooth. Add the egg yolks, one at a time, then add the brandy and orange zest. When everything is well combined, transfer to a large bowl and fold in the chocolate and the chestnut mixture.

Whisk the egg whites to stiff peaks and beat 2 tablespoons into the cake mixture to loosen, then fold in the rest. Tip the mixture into the prepared pan, level the surface and bake for 30 minutes until risen and firm to the touch. Leave to cool for 10 minutes, then carefully turn out onto a wire rack. Remove the baking paper and leave to cool completely.